Shaun McNiff, Lesley University

(This is the pre-published version of the full article, which will be published on CAET 6(1), 2020, summer issue)

“There are tears on the flowers, who feel the times.”

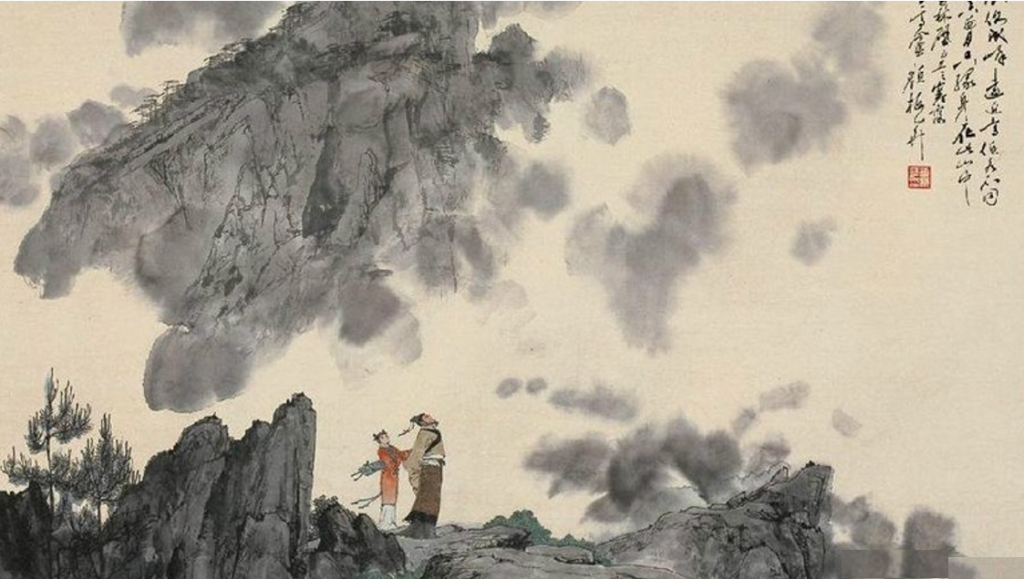

Du Fu (712–770), Spring Scene, circa 757

Pándēmos—Common to All People

When Tony Zhou initiated the idea of a special issue focused on the coronavirus in January 2020, my reaction was compassion for the threats engulfing the Wuhan region that I could only imagine from a distance. At that time I experienced Kong Xiangdong’s hauntingly beautiful musical response featured on TV Shanghai https://vimeo.com/396117953 and read the early drafts of Tony Zhou’s article on viral contagion and Guo Haiping’s reflections on creating artistic immunities to viral aspects of consciousness.

These first submissions to the journal aroused my sensibility to the interdependence of the whole human community (McNiff, 2018) and how the dark forces of the pandemic could enable art to realize its deepest purpose while furthering bonds with others – things that disturb and threaten us stimulate the making of life anew. I appreciated how experiencing vulnerability and empathy, “to feel the times” during a difficult period as Du Fu says, reinforces how the wound is an opening to the soul.

In the case of the coronavirus, the wound is collective. It opens to the personal and world soul, the anima mundi. It cannot be separated from the whole of nature and the interrelationships of all participants, large and small.

The word pandemic derives from the Greek pándēmos – common to all people. There are infinite differences amongst the human community, both innate and culturally created, but the COVID pandemic has galvanized awareness of what we share and the forces of nature that transcend our differences. The virus threatens every person and moves freely without discrimination from one to another. As a harsh force of nature, it can mobilize a united response necessitated by the unavoidable interdependence of life in both positive and negative forms.

In this issue, Tony Zhou’s discussion of the biochemical composition of the virus offers a perspective that requires consideration of nature’s fundamental processes that hold us all and to which everyone contributes as a necessary participant. Cheng Yang reiterates how viruses are elements of nature, causing pandemics when mistreated by humans. These reflections on organic life are paired perfectly with Guo Haiping’s discussion of the viral dimensions of language and ideologies which tend to block access to the unseen processes of nature. The complementary deliberations affirm how acts of creation and art healing are forever engaging conflictual and challenging substances and putting them to use in creating new life and infusing persons and communities with creative energy, a process appreciated in China for centuries, as inner alchemy, neidan (McNiff, 2016, 2018).

Natural Experiments in Art Healing Happening Worldwide

As COVID-19 first began to afflict East Asia and Europe I was struck by how unplanned and natural experiments inspired by threats to our existence, not only affirm the transformative nature of art healing but also the resilience of the human spirit. In keeping with my lifelong work with art and well-being, spontaneous creative expressions are responding to the crisis throughout the world and shown via the Internet as documented by articles in this issue.

Natural experiments are empirical occurrences in nature and human experience that happen beyond the control of the persons who study them and their outcomes. They are perfectly suited for understanding artistic experiences which are in so many ways antithetical to fixed procedures and controlled research designs established in advance. The worldwide artistic responses to the coronavirus offer ideal conditions for illustrating how art heals. Artistic expression requires freedom to manifest itself most completely and thrives on unexpected and unprogrammed imagining (McNiff, in press).

In addition to the use of artistic expression during the health crisis, an even larger and new natural experiment concerns the use of video and digital media for artistic communication. Yongwen Peng’s article describing online poetry recitations at the height of the epidemic in China in early 2019, Wei Zhang’s description of dance furthering well-being, and the reflections on artistic expressions in digital meetings by Steve Harvey et al. and Marcia Plevin and Tony Zhou, offer evidence of art’s unique power to heal and establish supportive communities when physical contact is not possible.[1]

The online poetic “outbreak” in China is consistent with how poetry has always been the accessible artform that the public at large engages in times of personal and social upheaval. It occurred suddenly as an innate and natural way of transforming distress into an affirmation of life.

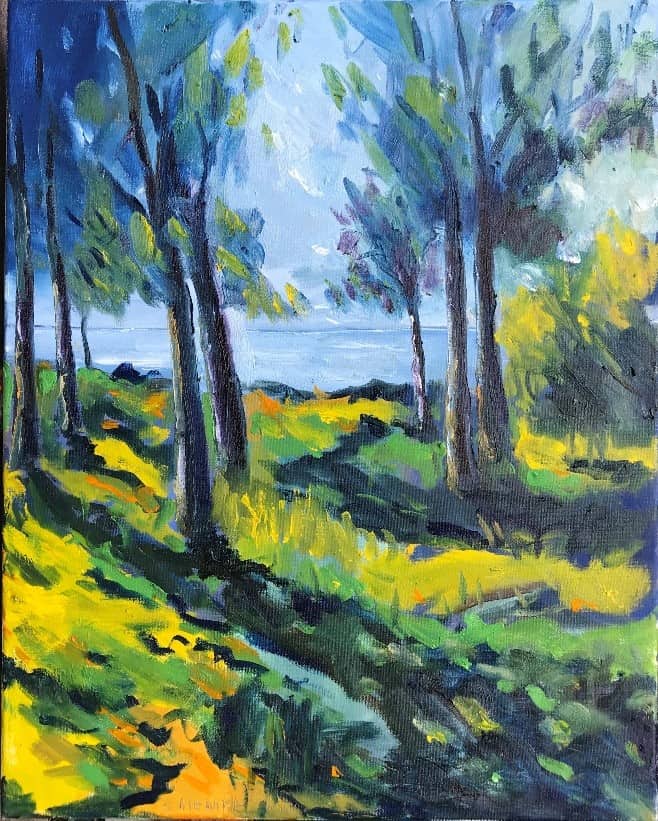

As with Du Fu’s classic poem Spring Scene written amidst widespread destruction and rebellion within the Tang Dynasty and which has many English translations, new life is generated by creation in difficult times; spring growth and renewal persist despite the catastrophic loss of life.[2] Du Fu, one of China’s most celebrated poets and many think one of the most significant in world history, experienced great hardship during the 8th century turmoil, and the lasting appeal of his art can be attributed to the distinctly Chinese attentiveness to the processes of nature giving hope and solace to the human spirit. His poetry, like Chinese landscape painting, position the human presence reverently within the larger Tao of nature. In his early and revered poem, A View of Tai Shan (Mount Tai, a mountain in the Shandong Province), written after failing the imperial jinshi exams in 735–736, Du Fu turns to nature for sustenance— “Inspired and stirred by the breath of creation…I bare my breast toward opening clouds” (Davis, 1962). The art medicine in this case is a reflection on nature as a source of inspiration, wonder, and support while channeling its creative energy.

History continuously shows through the presentation of “art evidence” how creative expressions transform difficulties into affirmations of life. In this era insisting on “evidence-based research,” arts and health disciplines are generally unable to appreciate this (McNiff, in press), even as the evidence is widely presented in public media. Art is being generated and shown today throughout the world in response to the pandemic in what is emerging as possibly the most comprehensive natural experiment in history documenting art healing. Kong Xiandong’s music video was the first instance of this that I witnessed in February 2020 and it was followed by an ongoing worldwide “surge” in artistic responses being posted online from China, Italy, the United States and other countries – instrumental music played from balconies, neighborhoods singing together from open windows during lockdown, private home performances shared internationally – the documentation of which will be a major future undertaking.

Science is not necessary to prove the value and healing effects of these processes; they speak convincingly for themselves. We should also note how the worldwide and concurrent manifestations are perhaps unequalled in terms of “sample size” with nothing like this previously occurring in human experience. Scientific inquiry is an altogether different realm, obviously and urgently contributing to understanding and ameliorating the coronavirus pandemic and ultimately preventing it in the future. Advocacy for art and its evidence does not question science and its primary role in public health. It is a plea to the arts and health domain to finally realize that art cannot be reduced to science, as potent as the latter has become in our era. These incessant efforts attempting to justify art healing through something other than itself diminish art’s natural medicines. Rather, art functions as a partner and co-creator making its unique contributions to well-being, generating outcomes distinctly different from those of science.

All Creation Is an Eco-system

A crisis that I first experienced vicariously from a distance became for many months a sustained and close presence while living in what was the epicenter of the disease in the northeastern United States. As I write what is perhaps the final contribution to this special issue in July 2020, the realities of COVID-19 are all-encompassing, changing exponentially, too vast for any attempt at description, and clearly with us for the future. The heartache extends from the universal threats to all human life to the inequities of contagion, impacts, resources, and healthcare across communities and the countries of the world. “The tears on the flowers” are especially focused on the elderly, the indigent, nursing home residents, and the lives lost of many serving them.

What has been consistent from my first reactions to Wuhan is how artistic responses to the pandemic affirm our human community and mutual existence and responsibility. With its East–West mission, Creative Arts in Education and Therapy (CAET) is a journal focused on the role of art in the reciprocal relations of peoples and environments. Actions in one sphere generate effects in others. It has been some consolation during the extremes of the coronavirus lockdown to continuously imagine that small and seemingly isolated acts, thoughts, and expressions do in various ways contribute to existence beyond the immediate context. In this sense, all creation is an eco-system of reciprocal relations. It is important to note how the articles in this issue written by authors in China underscore respect and cooperation with nature, and how well-being is furthered when as Cheng Yang says, all of the participating elements are closely attuned to “their ‘Tao.’”

Creating New Life

As dispiriting as the pandemic is now and with no ability to predict where it is going, I maintain a faith in creative transformation and the changes that will emerge from it. In a September 11, 1994 letter to me, Rudolf Arnheim (1904–2007) wrote of how chaos is purposeful in its “groping…for a new, more complex sense of order.” He often mentioned Carl Rogers, who like Lancelot Whyte [referenced in Entropy and Art (Arnheim, 1971)], believed in a “formative tendency” (Rogers, 1978), or “morphic tendency” (Whyte, 1974), which continuously makes new life from destruction and entropy within supportive environments. Rogers, acknowledging Whyte’s influence, described how this force can be observed in every dimension of the universe and like ch’i, which we have described in this journal as creative energy (McNiff, 2016), it permeates all facets of life. The evidence of these principles is offered by the ongoing process of artistic expression throughout the current crisis.

As this special issue was taking shape, I

doubted that I could say anything of use in response to the massive and ever-accelerating

complex of the coronavirus pandemic. It was and is too big. But I realized that

my life’s work concerns the engagement of difficulties as sources of creative

energy and transformation in individual and community lives, and that I must engage

the extraordinary conditions of the present. The crisis offers so many

illustrations of how art heals. Even as the extent of the pandemic diminishes

all individual efforts to transcend it, we can make new life, and we can do it

best together, arguably most effectively and naturally in difficult times.

In fallen states, hills and streams are still there.

The city is in Spring, grass and leaves abound.

There are tears on the flowers, who feel the times.

Birds startle my heart, they too hate partings.

(Du Fu Flowers, translated by Liu, 2020)

Many of the translations of Spring Scene (often entitled Spring View), similarly personify the flowers – “Moved by the moment, flowers splash with tears” (Watson, 2002) and “Stirred by the time, flowers, sprinkling tears” (Owen, 1996).