(Image courtesy of Dr. Thania Acaron)

An Arts Based Inquiry into the Cross-Cultural Emotional Climate during a Time of Political Tensions

东西方的身体对话:一种基于艺术的政治紧张时期跨文化情感环境的探讨

Steve Harvey1, Tony Y Zhou2, E. Connor Kelly3, and Joan Wittig4

1University of Guam, Guam

2Inspirees Institute, China/The Netherlands

3Authentic Movement Australasia, International

4Pratt Institute, Creative Arts Therapy, USA

Abstract

This article reviews an arts based project that came to completion in Shanghai during September 2017. During this project, a group of people interested in creative arts therapies from the USA and China used physical storytelling (PS) from both Eastern and Western perspectives to investigate the emotional climate of our contemporary world. In this project, participants introduced stories related to their current life experiences and a small group developed dance improvisations as an initial response to the stories. A larger group then used arts and poetry to express their reflections – leading to the development of metaphors that moved beyond the initial story material to express multiple personal and social aspects not apparent in the initial narrative. As this project was collaborative in nature, several common themes and images emerged. Although initial episodes introduced the theme of individual struggle, this expanded into a metaphorical exploration of general human struggle with larger social and natural forces. The final episode included movement, arts and fairy tale images that suggested a developing creative partnership between the East and West.

Key words: Arts based research, Physical Storytelling, Dance/Movement Therapy, Creative Arts Therapy, Cross Cultural Inquiry

摘要

本文回顾了2017年9月在上海完成的艺术项目。在这个项目中,一群对美国和中国的创意艺术疗法感兴趣的人使用东西方视角的身体故事(PS)来调查我们当代世界的情感环境。在这个项目中,参与者介绍了与他们当前生活经历相关的故事,一个小组开展了舞蹈即兴创作作为故事的初步回应。然后一个较大的群体使用艺术和诗歌来表达他们的反思 – 导致隐喻的发展超越了最初的故事材料,表达了在初始叙事中不明显的多个个人方面和社会方面。由于该项目本质上是协作性的,因此出现了几个共同的主题和图像。虽然最初的剧集引入了个人斗争的主题,但这些扩展为对具有更大社会和自然力量的一般人类斗争的隐喻探索。最后一集包括运动,艺术和童话形象,表明东西方之间正在发展创造性的伙伴关系。

关键词:基于艺术的研究,身体故事,舞蹈/动作治疗,创意艺术治疗,跨文化探究

Physical storytelling workshop in Shanghai, China, Sept 2016 – An art based inquiry into the Cross-Cultural Emotional Climate during a Time of Political Tensions. Watch the video

- Introduction

Our contemporary world is developing a rapidly escalating complex emotional climate. Current news accounts highlight several issues that contribute to such an escalation and include controversies about climate change, numerous political conflicts, the widely acknowledged negative effects of communicating via the internet and social media and growing unease in many countries’ economic and political relationships. In this project, a group of dancers from China and the USA came together to use physical storytelling in an arts-based inquiry which would investigate the personal experiences and commonalities we felt we may share in this present social context. We had one central question that we wanted to address – what does it feel like to live in the world today? As each of us came from different cultures and did not share a common primary language, however, a second question emerged; how could we communicate our personal experiences to one another within the group?

Arts Based Inquiry

Arts based inquiry (McNiff, 1998, 2013, Ledger & Edwards, 2011, Hervey, 2000, Moon, 1997, & Leavy, 2015) involves using artistic methods for gathering, analysing and presenting findings of a central question or point of interest. These authors conclude that arts processes are central to every part of this style of inquiry and are not merely an illustration of other verbal methods. (Edwards, 2016) has proposed that arts based research processes introduce an important area for development within the field of creative arts therapies.

When using arts based inquiry, researchers follow a creative process in order to investigate areas that are not easily described verbally but are related, instead, to the personal and emotional experiences of those involved in the project. In using such an arts based process, researchers often begin with a specific area of interest. The main questions subsequently emerge through the reflections of artistic expressions produced in response to this initial area of interest often in a non-linear manner. The basic assumption of such research is that important artistic expression can be produced when researchers have a close personal experience with issues being investigated within the project and that such an expression enhances the participants’ overall awareness of their area of study.

When researchers use this process, care is required to clarify such expressions by using a process of ongoing creative reflection to refine final results in order to find aesthetic relevance, to communicate the complexities of subjective experience with universality, and to help the methods fit the questions asked (McNiff, 1998, 2013). Through this project, we assume that the creative metaphors of our improvisation accurately reflect our cross-cultural experiences with each other in this current world climate and that such clarity will contribute towards a more general understanding of the inner emotional world that many others now find themselves moving through. To this end, we used several modes of expression as reflective processes to better refine our expressions.

Patricia Leavy (2015) describes the main strength of arts based inquiry as providing an avenue to address questions that cannot be answered in any other way. As the arts are based on metaphor, artistic expressions can reveal multiple realties at the same time. According to Leavy, dance can be used to explore an emotional and embodied aspect of experience. By using dance improvisation as an initial expression of extending the verbal material we began with, our goal was to subsequently develop new metaphors that would connect our physical and emotional experiences with our verbal reportage of events that had personal significance.

One of the outcomes of arts based inquiry is that the connections between personal experiences (or micro level) can be related to a larger context (or macro social level) through the metaphors we co-created. Within these improvisations, such possible connections between our physical and emotional experiences and the larger world context offer a means of viewing how our subjective day-to-day lives fit within a larger contemporary social climate. These characteristics of an arts based inquiry are well suited to meet the goal of the current inquiry in making sense of the present day world among participants who do not share a common primary culture.

Physical Storytelling (PS)

The main activity of Physical Storytelling (Harvey & Kelly, 1991, 1992, 1993, 2016, 2017a, b, & Kelly 2006) involves a small number of dancers creating movement improvisation in response to events that have been presented verbally. This form has emerged from contact improvisation (Pallart, 2008), Playback Theatre (Fox, 1994) and from authentic movement (Pallaro, 2007). The goal of such movement is to explore the interactive dynamics associated with interpersonal context in a physical sense and to uncover the emotional themes which underlie more concrete actions presented within a verbal narrative. Dance improvisation is used in this way to illustrate a “story under and within the story” (Harvey & Kelly, 2016) by providing an audience with a moving screen that can stimulate their active imagination through a process of projecting elaborated responses of the verbal material onto the physical interactions of dance. Often such projections and images relate to emotional material and creative responses which have not been apparent in the initial verbal presentation. In Physical Storytelling (PS) improvisational dance is used to transform the performance from a literal representation of an event into a much more abstracted metaphorical movement that can reflect multiple meanings connected through a dancer’s shared physical presence.

PS has been presented more completely in earlier articles (Harvey & Kelly, 1991, 1992, 1993, 2016, 2017a, &Kelly, 2006). For those readers who have difficulty accessing this material, Harvey & Kelly (2017b) have recently presented PS in a podcast available at http://www.mindyourbodydmt.com/21-physical-storytelling. Only a brief review of elements used in this project will be reviewed here.

Elements

The components of PS include a leader (conductor) and an ensemble of movers who are familiar with interactive dance improvisation.The role of the conductor is to listen, to support and to help the tellers as they present their story. In this project, individual participants were asked to present a verbal narrative about their experiences of the contemporary world. The conductor then organized a movement improvisation using casting and presented a score or basic structure to fit the verbal narrative. Following this, the conductor guided the group in producing arts-based responses (both in art and poetry) to the movement improvisation to express their experiences witnessing the movement immediately following the dance.

Scores

PS uses basic improvisational structures to help connect dance improvisation episodes to a verbal narrative and to allow the dancing to become be more organized and visible for an audience. These structures are identified as scores. The scores used in this project include:

Solo and Solo with a prop (E.g. Scarf). In this score, a single dancer performs a solo improvised movement. A prop such as a scarf can be used. Within PS, the mover uses his/her awareness of their physical experience to generate the dance in a moment-to-moment fashion rather than try to follow any intellectual or prearranged structure to mimic or pantomime the verbal narrative. Both the solo and solo with a prop are useful ways of making a visual or sensual metaphor from verbal stories that include several people and events. A solo dancer’s changing improvised movement qualities can become a representation of the felt emotional qualities that underlie an initial verbal narrative despite the number of characters involved in the initial telling.

Three Stops. In this score, three dancers improvise movement interactions with each other and come to complete stillness together on three occasions. The last stillness defines the end of the dance. During each period of stillness, the dancers use their new shape to change their movements by using the new physical sensation drawn from their still shape to develop a different overall dynamic in the scene that follows.

Three Solos. In this score, three dancers enter the dance space with each taking a unique still shape. The dance then proceeds as each dancer improvises solo movement around the other two dancers who remain in stillness. The order of the solos is not preset but is part of the improvisation. The scene ends when the final solo is completed.

The structures of three stops and three solos are used to clarify the time progression of the dancing with a beginning, middle and end or the past, present and future of a narrative. This representation offers an avenue for the audience to view the dancing in relation to a beginning, middle and end, or a past present and future of a verbal narrative.

Duet. This dance involves two dancers developing an improvisation using the qualities of their physical interactions as a way of guiding their movement. The duet can be used with stories relating to the inner thoughts and dilemmas of an individual protagonist.

Fairytale. In this structure, one or two dancer/s perform(s) an improvisation while another improvises a verbal fairytale in response to the movement. The goal of this score is for the poetic and movement improvisations to develop a unified joint expression that incorporates both a verbal and a nonverbal modality. The ending place is not preset but emerges naturally. The goal of the fairytale is not to produce an allegory of the verbal story but rather to create an abstract improvised form that intertwines both movement and verbal imagery from which the audience can use their imagination to find new personal connections. The Fairytale form is best used for stories that are complex or do not have a clear plot structure – such asdreams or highly emotional events. The Fairytale structure can also be used to summarize several narratives and is often used at the end of a series of dances.

Using group active imagination through projection onto the movement:

Another important element of PS is encouraging the audience to use their active imagination while watching the movement improvisation and to express what they see or feel in response to this movement. This part is seen as essential to developing an “exquisite communication” (Kelly, 2006) between the dancers and those watching – a communication that goes beyond the more typical performing to an audience. The goal of the PS is for the dancers to become a physical/emotional screen for the watchers – enabling them to become actively aware of their own experience while witnessing the dance. In this project, after each improvisation the audience responded using art and poetry using their primary language. These responses were shared in a process in the larger group and within the smaller groups.

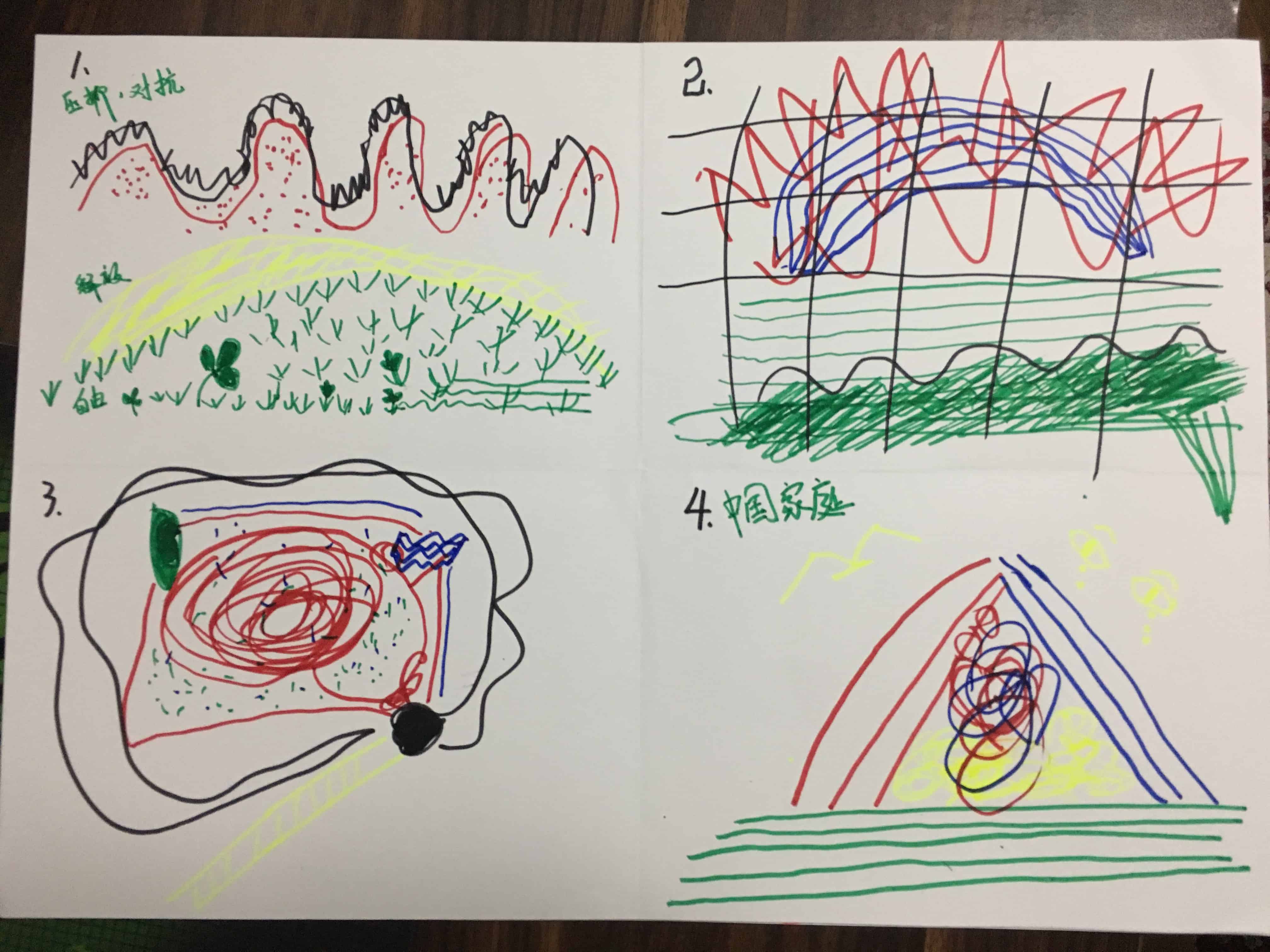

Figure 1. Dance improvisation using responsive shapes and efforts to make a moving screen for a projection of images to extend the verbal narrative.

Using improvisation as a research process:

Finally, PS is based on improvisation so that, in arts based inquiry, the movement episodes and other art expressions are not known beforehand. Improvisation is seen as the key active ingredient of the research process. The dances and subsequent audience responses that emerge are the results in a newly expanded understanding of the initial question that emerges from the creative process. Another aspect of this improvisation is that it is assumed that each episode and subsequent audience responses will influence the episodes that follow in an emergent manner. The new questions and themes that will develop are a means of building layers of complexity into new understandings. The result is assumed to offer the summary data to the main purpose of the inquiry. This final result is initially unknown and is what is discovered through the completion of the process. While the individual episodes have their own unique contribution, the overall project is meant to be considered as a whole.

2. The Project

Dancers and Setting

The project was initially set up for a small group of dancers (5-8) drawn from a larger group of professional creative arts therapists who had worked together previously and were meeting for a conference in Shanghai, China, in September 2017. Unfortunately, several of these professionals were unable to travel and so had to withdraw. Coincidentally, the host for the conference in China (TZ) was able to arrange another conference at a large Chinese university in which Physical Storytelling and other dance therapy methods were presented to arts educators over a two day period. There was high interest in PS. Initially, many more people wanted to participate than was reasonable and approximately 35 to 40 participants attended an initial six hour introduction to PS.

The two leaders (SH and TZ) decided to include many of these participants in the project. Finally, only the authors SH, ECK and JW participated as representatives from the West. Author TZ from the Inspirees Institute in China participated as an experienced Creative Arts Therapist from the East. Another 15 to 20 members from the university workshop then joined the project a day after the workshops had taken place. These participants included some dance instructors from the university. Other local dance and drama teachers from throughout the area were also able to join.

Many participants had no formal experience or training in dance or improvisation. Several participants spoke little or no English. SH, ECK and JW spoke no Mandarin. Some partial translation occurred during the project to help the group understand (in each language) the essential details of the stories and of the process, but no simultaneous translation was formally undertaken. The workshop members from Shanghai had no introduction to PS or to the current project prior to this workshop; they chose to attend as a matter of personal curiosity. Such developments made the question of verbal communication incredibly complex and offered an opportunity to investigate how the communication of personal experiences might develop using interactions that relied solely on arts-based improvised expression.

The structure of the project

On the first day, the authors of the central articles on PS offered a workshop which introduced participants to the form. This workshop included improvisational interactive movement, the use of improvisation as an expression of active physical imagination, the concept of witnessing the movement of others and the interconnections between movement and verbal narrative. During this introduction, PS was used to present several personal stories within the group. The project was conducted during the afternoon of the second day.

Initial Stories

The two organizers of the project (SH and TZ) discussed how the initial verbal stories germane to this PS workshop could be generated. It quickly became clear that there was a difference between West and East when it came to public expressions of contemporary political content. In the West, political ideas, commentaries and news stories relating to contemporary politics were expressed more openly; such overt political expression did not occur in the same way in China. This difference led to a real dilemma; the content of possible stories that could be used (or offered spontaneously for the project) from American and Chinese participants were likely to be quite different. To address this, the leaders decided to alternate storytellers so that one story would be told by one of the American participants and then one by a Chinese participant. The project leaders accepted this difference in approaches to the expression of political events. An assumption was made that any story that had personal relevance to the participants could become a valid source of metaphor making and would add value to the inquiry whether the content was directly political or not.

3. The Initial Question and Responses

The initial question was introduced to the group at the beginning of the project. The question was: what does it feel like to live during this current time? We were particularly interested in what similarities and differences might emerge from those participants coming from the USA and those coming from China.

4. Review of Stories

A review of the story/arts based episodes was developed to organize the presentation of the material. This review included a short summary of the initial narrative story, an outline of the central movement qualities that emerged from the dance improvisations and the Fairytales that were part of these improvisations. Examples of the poetic and artistic responses were presented along with a description of how the final episodes developed from an initial verbal story into the multi-modal metaphors.

A link to the videos of the dance improvisations is provided for the online version of the article. This link can be used to view the series of dances. Notes corresponding to the beginning of each episode are listed alongside each story so that the readers can follow each video with the summary of each story. The Fairytales and verbal responses that were initially been presented in Mandarin during the project were subsequently translated into English.

We recognize that this use of video of the dance improvisations is an important means of communicating our findings. McNiff (2016) has pointed out that projects that use arts based methods need a way to present the results in way that looks and feels like the arts rather than relying on a verbal psychological translation of the expressions that develop from the inquiry.

Finally, a review of the gradual development of metaphor over the entire range of the project was presented in order to investigate the emergence of the general themes.

The first story– Taking a Knee (See video 0.17 to 2:35)

The initial story was presented by SH. This story was based a news story from an ongoing political protest occurring in the USA at the time of the project. In this protest, several African American professional athletes had begun to “take a knee” or kneel during the playing of the American national anthem prior to the beginning of their competition. Such an action quickly became a potent symbolic protest both of racial inequality and of ongoing police brutality towards minorities – especially young African American men.

During the week prior to this project (mid-September 2017), this issue had become highly visible and controversial within the USA – especially on social media. Immediately prior to the opening day of the project, the news from the USA reported that a young Caucasian woman – a professional singer who had been hired to sing the national anthem at the beginning of a professional football game in front of several thousand spectators and a national television audience – “took a knee.” Public reactions on social media to her gesture were immediate, numerous and quite emotional. While some people expressed support for the courage of the singer to express her personal conviction, a great many comments on Facebook and twitter included both death threats and wishes that she would die of cancer (Lindsey, 2017). The singer’s account of this event was presented in the following news story from the Washington Post.

I am a white singer. I still took a knee after I sang the national anthem at an NFL game. http://www.washingtonpost/news/posteverything/wp/2017/09/29.

After the story narrative was presented, the conductor set the improvisation up as a solo with a scarf as a prop. The performance, casting and conducting of this episode were spontaneous. After the dance was finished, the group responded using art work, verbal phrases and poetry.

A young Chinese woman was cast as the dancer. She began the improvisation with the scarf held tightly over her shoulders. As the improvisation proceeded, she threw the scarf onto the ground and pushed it along the floor. She then gathered the fabric and ended the piece sitting on the scarf itself. The dancer primarily used movement efforts that were based on high intensity bound flow and were particularly related to strength – that was until the final act of sitting on the scarf when she released into a more neutral state of tension and took a deep breath. At this moment she looked directly and calmly at the storyteller.

The initial story was presented by SH. Here is his poetic response to the dance written directly after the ending of the improvisation.

The weight of the situation/ The anger and defiance/ I am I am

The final breath before the next important step

I am now ready/I can see now

I can see myself/I can feel myself/I am at peace

I am my own mountain

I am my own tree

I am

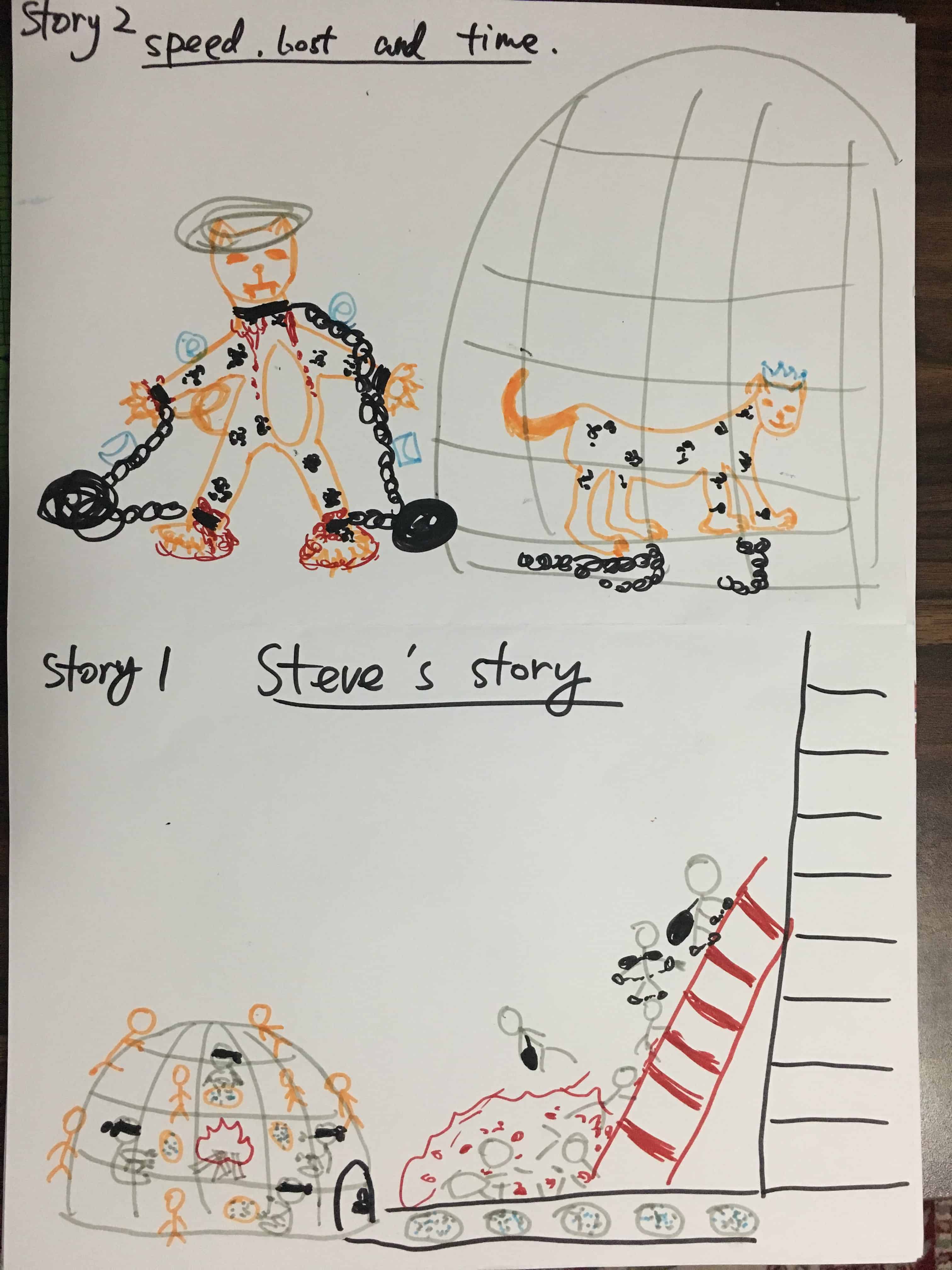

Figure 2. One art response from a participant/ audience member to “Taking a Knee”

The combination of the dance improvisation, the art and the poetic responses from the group indicated a pathway that reflected how the original news story of political protest was transformed into a metaphorical representation of personal emotional aspects central to making an important decision. The movement physicalized the strong physical inner feeling of struggle when a life challenge occurred that required a major “coming out’. The art expressions – especially when seen in connection to the dance – illustrated this struggle as an experience of being held in and even of feeling caged. Then, as the decision was made and expressed openly, a release and calmness emerged that brought a sense of becoming (and returning to) one’s natural self as expressed in the verbal imagery at the end of the poetry. The performance became a metaphor that could represent both a personal experience of decision making and a reflection of the honest and difficult expression of protest within a social context.

The second story-The Acceleration of Feeling (see video 2:40-12:02)

The second story was presented by the project co-leader from China. In this story, TZ told of his personal difficulty with the increased use of technology in the contemporary world. Previously, TZ had stated that he relied on the mail to initiate and respond to communication. He reported that prior to the introduction of communication through technological means (internet and social media), there had been time to prepare and thoughtfully consider a response in his written communications. Important feelings could be experienced and considered. However, the advancement of technology had now shaped communications which demanded an immediate response and the amount of communication had also increased significantly. TZ said that the speed of technology had now become overwhelming and distracting to the point where he now found himself separated from his feelings and from his sense of himself. The story was set up by the conductor as an improvised solo dance and a Fairytale. This Fairytale was improvised in Mandarin and was translated.

The dancer began standing under a large green scarf moving with high intensity quickness. This rhythm increased into efforts that echoed a growing sense of fighting and struggling until the dancer cast off the scarf. She then expanded her use of space. In the final portion of the improvisation, the dancer moved more slowly in a circle as she used her hands to travel up her body – touching herself from her feet and legs and then spreading over her back and torso. She extended her arms away from her body as she took a large breath and then brought her piece to an end by leaving the performing space. Such a sense of change in these dynamics of movement created a tangible physical representation of a sense of freedom that emerged after the fight to leave the distracting external forces and a return to feeling one’s own physical sensations. The Fairytale that was improvised alongside – and in response to – the movement is presented below.

The Fairytale of the Leopard

A leopard was covered by distraction and forgot where she was/ her passion, her freedom, the things she longed for.

She still had her strength and the core of her heart

One day she got rid of the things that were stuck around her/she finally found her peace, and strength, and freedom

She found herself

She found her place in the world

Figure 3. An art response from a participant/audience member to the dance improvisation for the acceleration of feeling

This combination of the Fairytale, dance and art work transformed the initial story into a metaphor for the experiences of expansion, lightness and freedom that come from the self-discovery of personal physical/sensory experiences after struggles with external realties. These arts expanded the original story of personal frustration and alienation into an expression that has relevance to the current social climate where important worldwide emotional communications occur rapidly through technology in ways that are both alienating and distracting. The episode also became a personal metaphor for finding oneself.

Third Story- The Death of Ocean (see video 13:43-22:30)

A woman from theWest (ECK) presented the next story. She stated that this story had been evoked from viewing the previous episodes and she had decided to tell it spontaneously. In her narrative, ECK told of witnessing an increase in bleaching (or whitening) in the coral reef while she had recently been scuba diving. Such bleaching was due to the warming of the ocean and was directly related to climate change. ECK said that she had only just started to see this bleaching at her favorite dive sites – and even though new fish life was being born there, the numbers had reduced greatly. This colour change indicated damage and showed that the coral itself was beginning to die. She stated that this whitening had significant ecological meaning and would lead to the death of the ocean as we currently knew it. This development had made a deep personal impact on her. The episode was set up by the conductor as an improvisation for three dancers with three stops.

Each dancer began the improvisation in the space using a differently colored scarf. During the initial movement scene, a dancer with a black scarf entered the interaction between the other two dancers. This dancer used slow sustained movements while the other two dancers moved in a free-flowing way with each other. As one observer noted after the performance, these dancers were like fish continuing their life without any knowledge of what was approaching.

During the second movement scene, this dancer covered one dancer with her black scarf and then wrapped it around the other. One of the ‘covered’ dancers pulled against this – using fighting efforts of quickness and high bound flow. The scene ended with two dancers motionless and covered by the initial dancer’s black scarf. When the original dancer moved away from the other two, they remained motionless. The movements she used as she backed away across the full performing space were slow and sustained. Her controlled and even use of time suggested a suspended state. This scene ended when this third dancer stopped some distance away from the other two. In terms of movement, this piece had a real sense of inevitability. The use of the black scarf with these slow, encroaching movements became a representation of the natural forces involved in climate change and also suggested an impending emotional tragedy.

In one response to this dance, a woman from China said that the dance also expressed what she’d experienced as she’d watched her grandfather dying slowly and had come to understand how helpless she felt witnessing the process of his death.

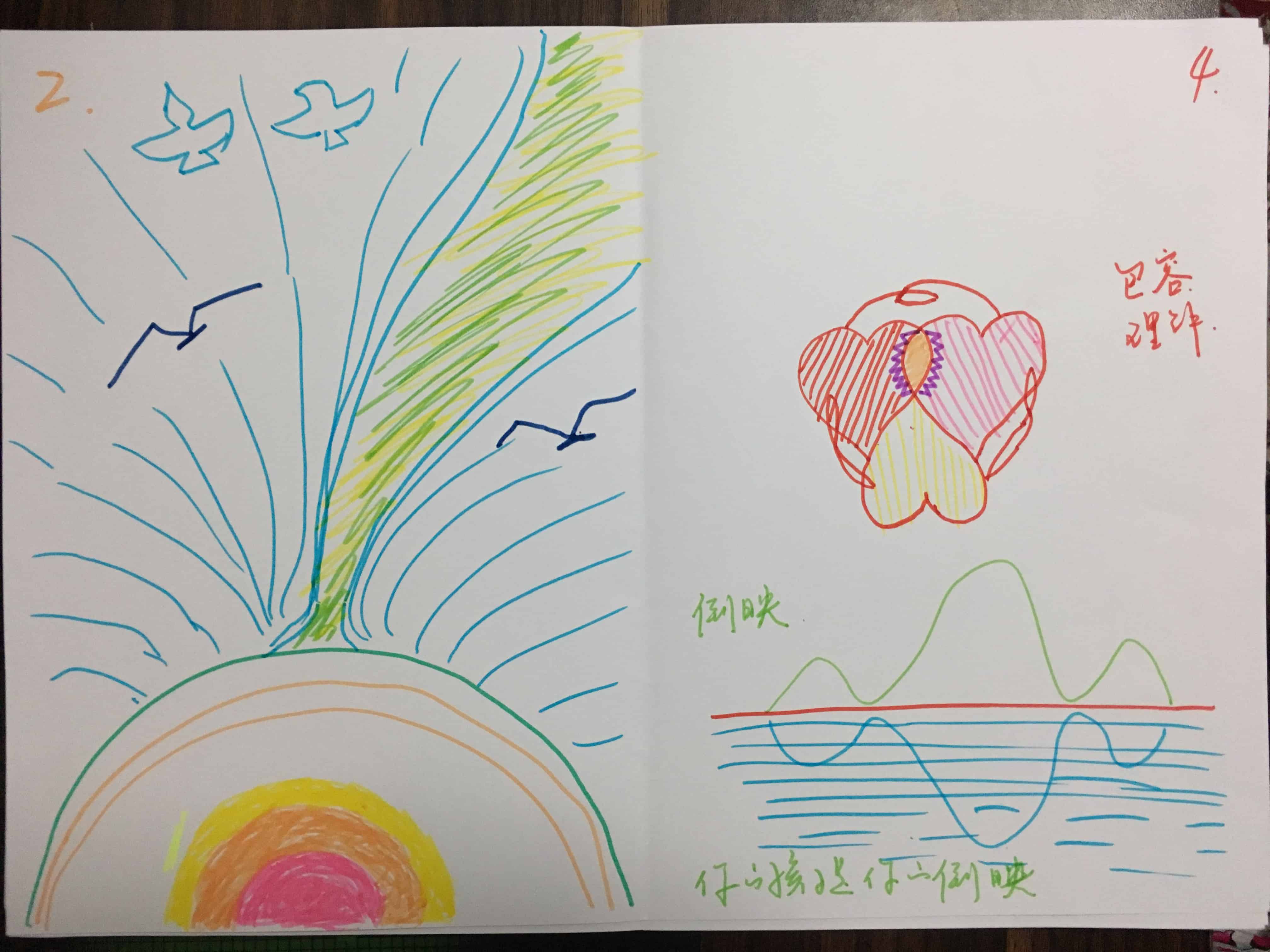

Figure 4. A participant’s art response to the dance improvisation of The Death of the Ocean

The poetic response from the teller

New life unfolding/ Is it enough? To bless us? To sustain us?

For us to respect? To protect? To understand and appreciate

What lay before us in plain sight/ What is beneath us

In our own depths

These movements, art, and poetic images combined to move from the original story into a metaphor about the sadness and helplessness that developed from the realization that an overwhelming force is changing our expectations of how life is unfolding. The metaphor suggested that such impending change could be a force of nature/history, something more personal or even a combination of the two. This episode not only became a metaphor for personal grief but also explored a growing sense of social dread and general helplessness in the face of the natural and political forces unfolding before us.

Fourth Story-Mistrust and Despair in a Family (see video 22:41-27:40)

The next story narrative was presented by a woman from China. She told how she had learned of the family situation of an acquaintance who had initially presented herself as having a very happy life. However she learned that the truth was very different. The husband of this acquaintance was currently spending a large amount of time in another city for work. Both the husband and wife had begun to wonder if each was having an affair with another partner. This situation had led to a marked increase in tension within the family and the growing mistrust was now contributing to their son’s difficulties in focusing on his preparations for a key university entrance exam – the result of which could profoundly affect his future. When asked by the conductor about how the story would end, the presenter said that she did not see an end to the situation within the immediate future. Both the conductor and the woman agreed that, given the current circumstances, the ending was likely to lead to an increase in despair.

The dance was set up as an improvisation for three dancers doing three solos. The initial solo was focused on the surface view of a happy family life. The second solo explored the growing development of a sense of mutual mistrust. The final solo represented the development of burgeoning despair. During the improvisations, the dancer who began the improvisation deviated from the score by continuing to move throughout the piece. This introduced an element of tension both for the ensemble and the overall creative challenge. The other two dancers did continue with the basic solo structure. The resulting conflicting movement improvisations led to dramatic interactions that increased a sense of unease throughout the dance. Such unexpected interactions contributed to a complex group movement that ended up representing a sense of unending interpersonal conflict where the dancers had little ability to arrive at any resolution.

All three dancers used strong bound flow which built into gestures of claps and slaps. These gestures were repeated in varying ways by the ensemble. Each dancer used such gestures as gripping her partners’ arms at various times. During the final solo, the last dancer placed her body on the other two in an attempt to end the piece. This movement was extended by a loud and dramatic sound from one of the other dancers. The initial dancer then lay on the floor in stillness to finish the piece. All dancers were on the floor as a final still sculpture. The dancers used the movement qualities of strength and quick bound flow (with little recuperation) as a theme. This overall quality of movement created a sense of struggle that observers knew could not end in a positive way; there was a palpable sense of a loss of freedom and of spontaneity.

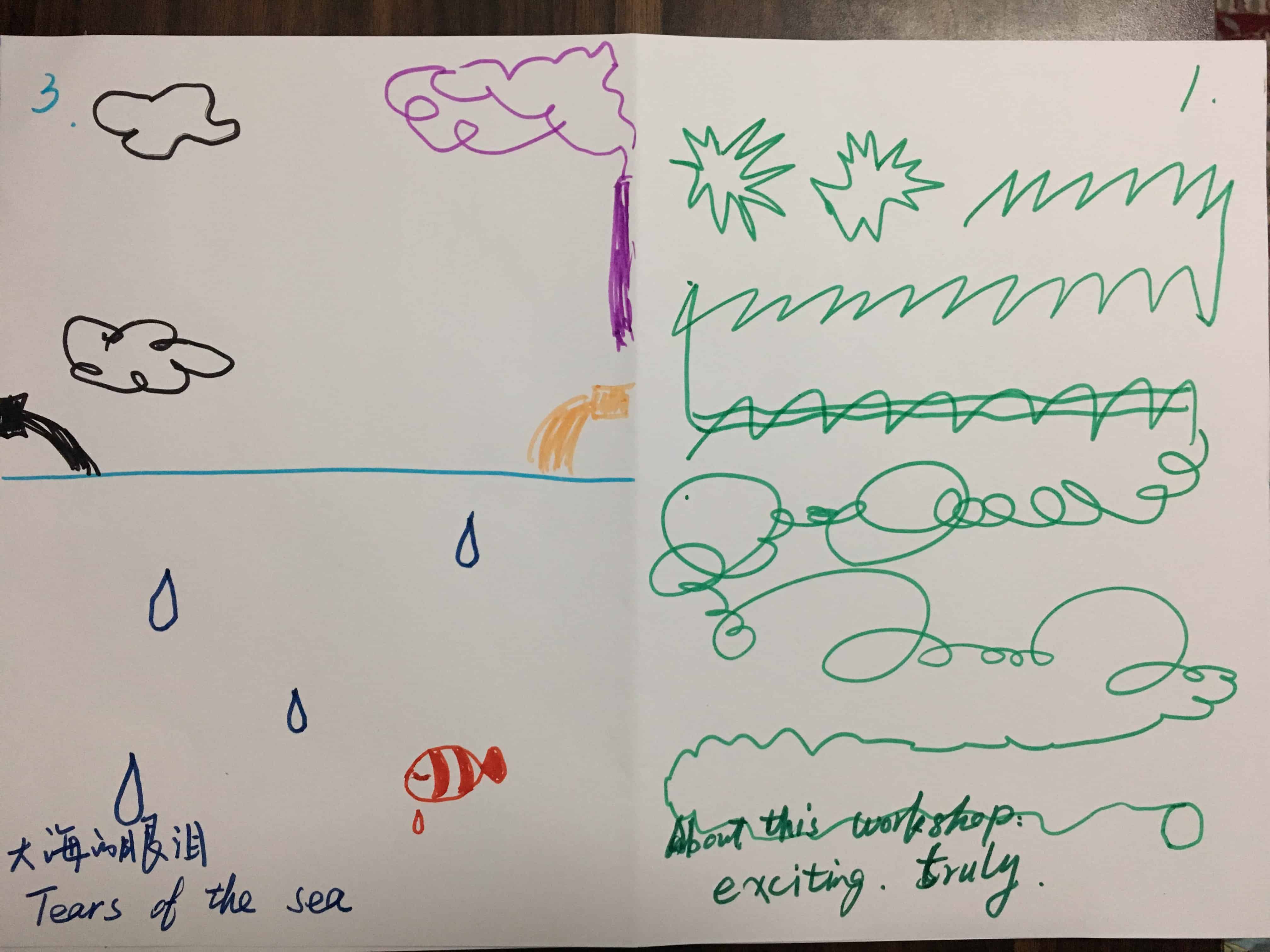

Figure 5. One participant’s art responses of the dance of Mistrust and Despair in a Family

Figure 6. Another participant’s art response to Mistrust and Despair in a Family

Comments related to this picture

Stick, Suffocating, Can’t move, Can’t move toward, can’t move away

Can’t follow my heart, How to get rid of this? whether to stay or whether to run

Try or give up

This episode expressed a quality of personal tension without release that, despite major efforts to find an end, could have no positive conclusion. The art and poetic images produced in response to the dance added to the sense of containment and inner tension that had been generated by the movement quality. The combination of these dance, artistic and poetic expressions moved the original story into a metaphorical expression of an entrance into a period of ongoing emotional constraint and immobility arising from a sense of growing mistrust and a subsequent trap of despair. This expression provided a view of an internal response to interpersonal conflict as well as introducing a theme that suggested the high and unresolved tension that could apply to many aspects of the current social and world context.

The final story – A Personal Struggle to Reignite Hope (see video 27:41-41:04)

A woman (JW) from the west presented the final story. She introduced thoughts about how she was considering finding a new political option in the USA that differed significantly from the system currently in place. In doing this, however, she worried that it might lead to a long period of struggle and more disappointing outcomes. During the summary with the conductor, she realized that taking this new option was a personal choice that included an emotional risk for her. The conductor asked JW choose two dancers and she selected two dancers from China. The conductor set up the PS as a duet with an improvised Fairytale that would be performed twice. SH created a Fairytale in English in response to the duet for the first episode and then the same dancers continued with TZ providing the Fairytale in Mandarin in the final scene.

The movement quality during these improvisations was different from the previous work. Both dancers used more free flow, had a more relaxed use of time, and covered a larger range of space. The duet moved throughout the performing space and even left the circle on occasion. The dancers moved easily through all body levels from standing, mid-range and kneeling to movement on the floor; they also developed a wide range of interactions from intimate movements with virtually no space between the bodies to being far part. After each movement phrase, both dancers used some time to recuperate before engaging again in an interaction. This style allowed interactions to develop somewhat more independently of each other and for those interactions to possess a variety of different qualities that were not as heavily influenced by the previous movement.

At one point, one partner leaped on the other’s back freely while the other dancer accommodated easily to his weight. The dancers playfully developed a range of interactive scenes and were frequently able to reverse roles. During the closing interaction, one dancer lay on the floor while the other crossed his arms over his chest. This dancer then ended the piece by lying next to his partner in the same position. This created several images which were peaceful, intimate and humorous and suggested both a sleep and a joint funeral.

These movement qualities offered a much larger range of interactive opportunities for new and surprising actions within the improvisations. The resulting dances suggested a style in which both creativity and change were possible and developed a sense of fun and pleasure from the mutual creativity. This episode developed an expression that provided new metaphors and images that created a sense of hope.

The English Fairytale improvised within the duet:

Once in a land so far away that no one could even imagine it/ there was not even a thought that this world existed. The living creatures of this world were half plant and half person. No one was quite sure how they could get along. Some things were quite frightening; sometimes it was like late night comedy. They were quite playful, these creatures. Absolutely nothing was out of bounds-they could do anything. Even Magic.

The Mandarin Fairytale- (English translation)

In the sunshine in the morning, two strangers meet each other on the street. They don’t know each other, so the meeting is a surprise for both of them. They see each other and ask themselves: can we be friends? Will we be friends temporarily or forever? How do I know if the other person is trustworthy? Perhaps we can start playing with each other and then watch the how other responds and see how far we can go? So let’s start being friendly with each other – teasing and challenging our partners step by step. Sometimes we’ll get confused and frightened because we still don’t know what is going to happen. The sun is shining and drawing us to the light. Is this sunrise or sunset? I don’t know. Perhaps this is part of the overall confusion and exploration. Even though we’ve had some fights, we know we can be companions for one another for, as a human species, we share things in common. When you lie on the ground, silent or dead, I will lie side by side with you. At that moment we will have peace in our hearts. At that moment we know we are just one part of the nature and whole universe…

Figure 7. An art response from a participant to A Personal Struggle to Reignite Hope

This improvisation transformed the original story (which had been about exploring new political options and personal risk) into a metaphor for engaging in new possibilities within relationships. The art reflected the sense of space generated within the movement and the central theme from this multimedia expression was that change could bring lightness to our relationships with others even without a palpable sense of outcome. The overall quality of this episode was related to the emergence of a feeling of hope through an ongoing process of creative engagement with others. The final impression was that a metaphor of change on both a personal and social level can emerge through a given process without any sense of the content or end point of what this change might be.

5. Reflections

We wanted to use specifically developed arts based expressions that we had created in order to answer the question “What does it feel like to live in the world today?” and to consider if there might be similarities or differences between those of us coming from the West and those from the East. We were also interested to see if we could find a way to communicate our personal experiences despite not having either a shared verbal language or common culture.

When the project was originally conceptualized, we assumed that the initial story material would be drawn from news accounts across Western countries (USA, Europe, and New Zealand) and the East (China). It quickly became clear, however, that public expressions of political/social thought and feelings differed greatly across these areas. Those from the West presented story material that was related to political issues: protest activity, the development of new political choices and issues relating to climate change. Those from China introduced story material which related to daily experiences – namely the use of technology (social media and the internet), and the conflicted emotional life of an acquaintance’s family. A difference did emerge in the kind of verbal narratives focusing on what influenced the participants’ experiences of the contemporary world. Issues pertaining to politics contributed more to the verbal narratives from participants who lived in the West, while participants from China were more influenced by narratives that had a day to day orientation.

Commonalities that emergedduring improvisations:

What emerged from the arts based improvisations, however, was that each of these stories contained themes of personal experience that were relatable no matter where the verbal accounts originated. Though we live in countries that expressed their public political concerns in unique ways, we found that there were several emotional commonalties that we shared in our improvised expressions. A dance focusing on a news report of political protest in the USA, for example, led to an expression of strongly personalized feelings related to decisions about self-expression. Many participants from China reported that they could understand the emotional importance these issues possessed for those participants who lived in the West because they’d shared a common emotional experience while watching an improvisation about the struggle for personal expression. The metaphors we co-created had both personal and social relevance for us.

The episodes all contained metaphors that could address both personally subjective experiences (micro level) while retaining connections to the larger social context of the contemporary world (macro level). Each combination of expressions provided avenues of expression for personal emotional experiences as well as a metaphor of social consideration. When these initial verbal stories were transformed into artistic improvisations, the episodes were able to address several types and levels of experiences simultaneously. For example, the story that related to climate change also (when presented in metaphorical terms) addressed personal experiences of the process of death for either a family member or the death of coral from changes in ocean temperature from global warming. In a similar way, when viewed through these arts based expressions, the story of family tensions became a way of representing the arcing movement from mistrust to despair within a contemporary emotional climate. These metaphors allowed us, as participants, to understand each other in ways that we could not manage before the project began.

The overall process of this project also offered a larger metaphorical examination of simultaneous personal and social experiences. We assumed that each story would contribute to the next in such a way that each new story would uncover a more complex aspect of the original question and images would develop which were unknown prior to the previous episode. The final story was assumed to represent a culmination of all these aspects with the outcomes emerging as a process. In review, the initial two stories developed metaphors relating to individual struggle whereas the two middle stories addressed emotional experiences related to larger social and natural forces and the final episode resolved some of the dilemmas raised throughout the process by introducing creativity as a process of change without any notion of an end result in response to struggle. This performance also introduced the concept of the emergence of a complex relationship arising from questions about an unknown partner. Metaphorical expressions focusing on the nature of creativity could also be related to the dilemma of political change which was introduced in the final story. This project also addressed the creativity involved in the development of friendships and the acceptance of others from different cultures.

One of the questions raised in the initial stages of this project was how the development of a means of expression could reveal our personal experiences while, in doing so, create a series of more universal images. We also wondered if we would simply be able to understand one another. As the project developed, however, we found that the metaphors created in performance represented personal and social experiences which were both varied and complex. These images were co-created with participants from two very different cultures and with no common primary language. Despite complex differences in the public expression of these participants’ political and social worlds, we found common ground and established an intimate communication using physical conversations which were followed by artistic responses – such a process occurring through shared creative expression. By utilising such a process, we developed a common language where each participant was able to contribute components of movement, art and poetic expression in a complementary manner. By fully participating together in the making of these images, our participants developed a shared sense of communication.

For the authors of this project, one of the more interesting metaphors that emerged was during the final dance/fairy-tale which addressed the issue of creative relationships and trust without guarantees or even guidelines and which focused on the relationship between contemporary USA and China within a changing world climate. Though the initial story began as a narrative of how political change in the USA required both risk and struggle, the final fairytales, art, and improvised duet introduced the theme of how friendship develops between strangers. Given that the initial part of the project involved participants from the West and East (and accepting increasingly complex relations between the USA and China in particular) the final dance offered an interesting and hopeful metaphor as to how our cultures might currently interact.

About the authors

Steve Harvey, Adjunct Professor University of Guam, Department of Clinical Psychology,. E-mail: saharvey1@yahoo.com

Tony Y Zhou 周宇, PhD, Director, Inspirees Institute, China/The Netherlands. ORCID:0000-0001-8099-6458 Email: t.zhou@inspirees.com

Connor Kelly, Director of Authentic Movement Australasia, International

Joan Wittig, Professor of Pratt Institute, Creative Arts Therapy, New York

Acknowledge

The authors wish to thank and acknowledge the support and efforts from the Department of Art Education, East China Normal University (Shanghai) and Inspirees Institute for the development of this research project as a means of engendering international collaboration.

References

Edwards, J. (2016): Researching the Creative Arts Therapies: Why we do it, and what it is meant to achieve. The Arts in Psychotherapy: 48, 1.

Fox, J., (1994): Acts of service: Spontaneity, commitment, tradition in the non-scripted theatre. Tusitala Publishing, New Paltz, N.Y.

Harvey, S. A. & Kelly, E. C (1991): Physical storytelling. Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth Annual Conference of the American Dance Therapy Association American Dance Therapy Association: Columbia, MD.

Harvey, S. A. & Kelly, E. (1992): Physical Storytelling: Applications in therapy and supervision. Proceedings of the Twenty-Seventh Annual Conference of the American Dance Therapy Association. Columbia, Maryland.

Harvey, S. A. & Kelly, E. C. (1993): Physical Storytelling: Witnessing and performance in supervision and therapy. Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth Annual Conference of theAmerican Dance Therapy Association. Columbia, Maryland.

Harvey, Ndengeya, & Kelly (2014): Using physical storytelling to understand youth suicide in New Zealand, DTAA Journal, Moving on, Volume.12, No1 and 2, 3-10. Dance Therapy Association of Australia, Melbourne.

Harvey, S.A. & Kelly, E.C. (2016): Arts based enquiry: Integrating narrative within movement. DTAA Journal, Moving on, Volume.13, No3 and 4, 2-9. Dance Therapy Association of Australia, Melbourne.

Harvey, S. A & Kelly E.C. (2017) (a) A look at the journey score in physical storytelling. DTAA Journal, Moving on, Volume.12, Nos.1 and 2, 3-10. Dance Therapy Association of Australia, Melbourne.

Harvey, S. A, and E. C. Kelly. (2017): (b) “21. Physical Storytelling.” Mind Your Body, Mind Your Body: A Dance Therapy Perspective, 9 Dec. 2017, www.mindyourbodydmt.com/21-physical-storytelling.

Hervey, L. (2000):Artistic inquiry in dance/movement therapy: Creative researchalternatives. Charles C. Thomas Publishers, Springfield, Illinois.

Hervey, L. (2004): Artistic inquiry in dance/movement therapy. (pp 181-205). In R. Cruz & C. Berrol (eds.) Dance/movement therapists in action: A working guide to research options. Charles C. Thomas Publisher. Springfield, Ill.

Kelly, E.C (2006): Physical storytelling, DTAA Quarterly Volume5, 1, 3-8. Dance Therapy Association of Australia, Melbourne.

Leavy, P. (2015): Method meets art: Arts based research practice: Second edition. Guilford Press, New York.

Ledger, A & Edwards, J. (2011): Arts based research practices in music therapy: Existing and potential developments. The Arts and Psychotherapy, 38, p 313-315.

Linsey, M (2017): I am a white singer. I still took a knee after I sang the national anthem at an NFL game. http://www.washingtonpost/news/posteverything/wp/2017/09/29.

McNiff, S. (1998):Arts-based research. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. London, England.

McNiff, S. (2013): Art as research: Challenges and opportunities. University of Chicago Press.

McNiff, S. (2016): Presentations that look and feel the arts in therapy: Keeping creative tension with psychology. In T. Zhou & Z. Moula (Eds.) (pp 1-11) . Proceedings of the 1st international symposium of creative arts and therapy: When east meets west- (ISCAET). Inspirees International Publishing.

Moon, B. (1998): Art and Soul. Charles C. Thomas Publishers: Springfield, Ill.

Pallaro, P. (2007): Authentic movement: Moving the body, moving the self, being moved Volume two. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. London, England

Pallart, C (2008): Contact improvisation: An introduction to a vitalizing dance form. McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, North Carolina.