Expanding Normality at the Edges of the Art World in China and Japan

by Shaun McNiff

An Interview with Raphael Koenig and Benny Shaffer: Expanding Normality at the Edges of the Art World in China and Japan.

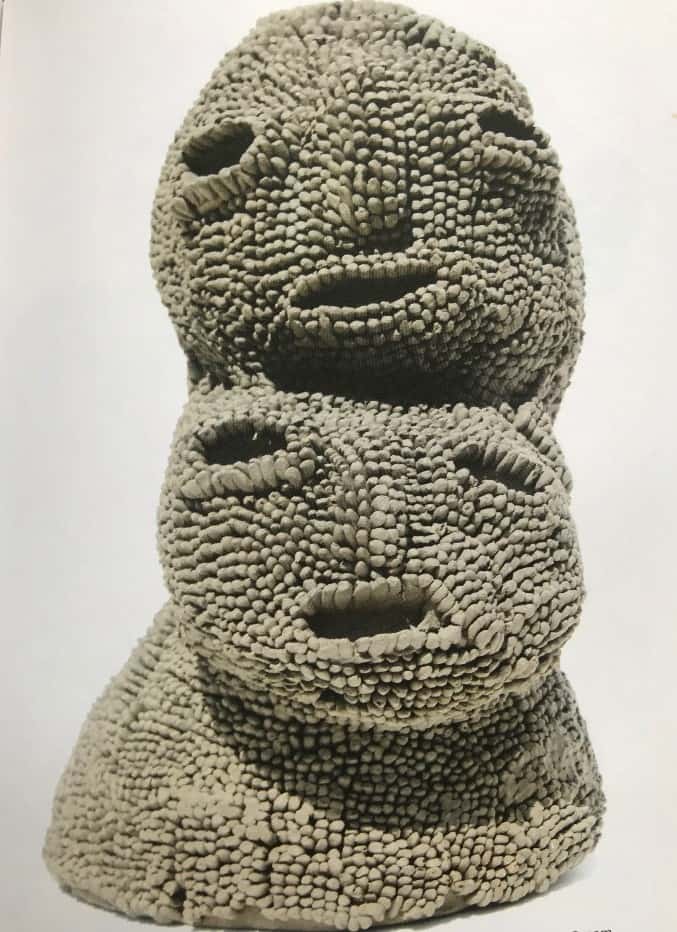

A Special Section on Eye Eye Nose Mouth: Art, Disability, and Mental Illness in Nanjing, China and Shiga-Ken, Japan, Harvard University Asia Center Exhibition, 2019

在中国和日本艺术世界的边缘扩展正常化

哈佛大学亚洲中心特展(2019)- 眼鼻嘴:中国南京和日本滋贺县的艺术、残疾和精神疾患

An in-depth interview with Raphael Koenig and Benny Shaffer exploring the development, goals, and outcomes of the 2019 exhibition and symposium at the Harvard University Asia entitled Eye Eye Nose Mouth: Art, Disability, and Mental Illness in Nanjing, China and Shiga-Ken, Japan.

2019年哈佛大学亚洲中心展览“眼眼鼻嘴:艺术、残疾和精神疾病”专题介绍,日本Shiga-Ken和中国南京。南京艺术展和Shiga-Ken工作坊以及哈佛专场以独特的艺术主张为特色,寻求改变社会对残疾人以及精神疾病的态度。这篇文章回顾了展览与目录,将东亚工作坊和艺术治疗工作室与西方进行相比较。

Shaun McNiff: Please tell us how you both came to exploring the art workshops in China and Japan; how you started to cooperate? How did the 2019 Harvard Asia Center exhibition originate and develop? What were your goals? Were there challenges? Are there particular people and institutions who helped make it possible?

Raphael Koenig: As we are working in the fields of Anthropology and Comparative Literature, respectively, it is very important for both of us to be able to exchange ideas with scholars who work specifically on issues related to the theory and practice of art therapy: so we are really grateful for your sustained interest in our exhibition.

Benny and I are both interested in exploring the margins of art, literature, and cinema, and focusing on lesser-known figures, movements, and phenomena that we feel are worthwhile: Benny is currently finishing his dissertation in Anthropology on the “edges” of the art world and entertainment industry in China, and I defended my dissertation in Comparative Literature, with a strong art historical component, on the relationship between the historical avant-gardes and self-taught art from the 1920s to the 1940s.

So this project felt like a natural way of combining our respective approaches: I have been working on historical self-taught art, but was interested in looking into the innovative contemporary approaches developed by these specific art workshops. Benny has lots of experience conducting anthropological fieldwork, which involves engaging with local communities and participating in their daily routines while attempting not to disrupt them.

We felt that what was often missing in the description of art workshops for people with disabilities, and probably of self-taught artistic expression in general, was a more rigorous attention to their individual socio-historical contexts: bringing the conceptual and practical toolbox of anthropological fieldwork into a project that is informed by more theoretical discussions on self-taught art and is concerned with questions of artistic expression, creativity, disability, and individual agency felt like the right way to go. We hoped to shift the discourses on these workshops.

The challenges were many. On a practical level, we had to figure out the logistics of shipping works across continents and coordinating with guests from China and Japan to bring them all together for the opening and symposium. But also on a more fundamental level, this is by no means an easy topic. How does one exhibit or talk about these works while trying to navigate the multiple ethical minefields that have to do with possible cultural appropriation of East Asian art or art produced by people with disabilities? That is why it was important for us to provide as much context as possible in the exhibition itself and the catalogue.

We are very grateful to Professor Karen Thornber, director of the Harvard University Asia Center, who supported our project from the start. She is involved in groundbreaking work on medical humanities in East Asia, and was interested in displaying visual works produced by people with disabilities in China and Japan at the Asia Center.

We are also grateful to Masato Yamashita, director of Atelier Yamanami, and Guo Haiping, director of Nanjing Outsider Art Studio, for their warm welcome and incredible help throughout the project: they really supported our endeavor from the start, and went above and beyond to make sure that our stay at their workshops was as productive and enriching as possible.

And we owe a huge debt of gratitude to the artists and staff of each workshop, who openly welcomed us into their communities, were incredibly generous with their time, and allowed us to be part of their lives and to document and share their work with international audiences.

Yukiko Koide, a Tokyo-based gallerist who is also a leading expert of Japanese self-taught art, supported us every step of the way: from first email introductions to the practicalities of shipping valuable works from Japan for our show, and as an interlocutor in helping us figure out the Japanese side of the equation.

SM: How would you compare the work that you have observed in China and Japan? Your catalogue emphasizes the cultural context of each artist’s work as well as the particular orientations of the workshops that support them. Daniel Wojcik shares your concerns about how these individual artists work with in relation to the values and structures of their particular communities and contribute to them. He feels that this feature has not been sufficiently addressed in the history of self-trained artists dealing with various disabilities and health challenges. While their artistic expressions may manifest qualities that are shared with others throughout the world, they are nevertheless fundamentally working within specific places and historical circumstances like any other artist and not to be grouped into an ‘outsider’ category or ‘population’ which diminished their distinct personhood and artistic accomplishments. You also emphasize these points in the exhibition catalogue.

Raphael Koenig: We absolutely agree with Daniel Wojcik on this point. In fact, my own research has been dedicated to showing that “outsider art” or “art brut” are categories that tell us relatively little about the provenance or meaning of these works. For instance, what relationship would there be between works created in the context of a care institution (psychiatric care facility, workshop for people with disabilities, etc.), within a purely independent self-taught practice (such as the Watts Towers in L.A.), or as part of a religious or para-religious experience (for instance the drawings of Czech psychic Anna Zemánková)? These works were mostly lumped together in one category that only makes sense if we take into account the specific agendas and aesthetic sensibilities of people like Jean Dubuffet, who in the immediate postwar period were attempting to define a “primeval” locus of artistic expression. The institutional clout of foundations and museums that perpetuate his legacy aside, there is no compelling reason why we should rely on his theories. Works by self-taught artists often seem to be used to support the validity of Dubuffet’s claims, as mere illustrations in a sense. But critical discourses should arguably be made to serve the artworks and allow for a better understanding of them, not the other way around.

Works produced in art workshops for people with disabilities in China and Japan have been exhibited internationally in the past (most notably at the Collection de l’art brut in Lausanne and at the Halle Saint Pierre in Paris), but generally there seems to have been little engagement with the concrete reality of these workshops: How do they operate? How are they perceived in their respective societies? Do they themselves defend a broader agenda of social change and heightened integration of people with disabilities within the rest of society?

All of these are questions that we find extremely relevant, but unfortunately in many of the Western institutions that exhibited these works, a lack of proper research on these workshops led to generalizations, for instance focusing on the neo-romantic cliché of the isolated “brut” artist.

The works we featured in the show undoubtedly display strong individual features, idiosyncratic techniques, and so on, but one should not underestimate the importance of the fact that they were made possible by a collective structure (namely the workshop) meant to empower artists with disabilities. There is nothing wrong with being part of a collective; saying that a late nineteenth century painter was part of a group that was based in Pont-Aven, Brittany, or in the Hudson River Valley does not diminish their individual achievements. It is meaningful context. There is no reason to treat self-taught artists any differently.

SM: Are their qualities shared by both workshops? Common features in both the missions of the workshops and the art that is generated?

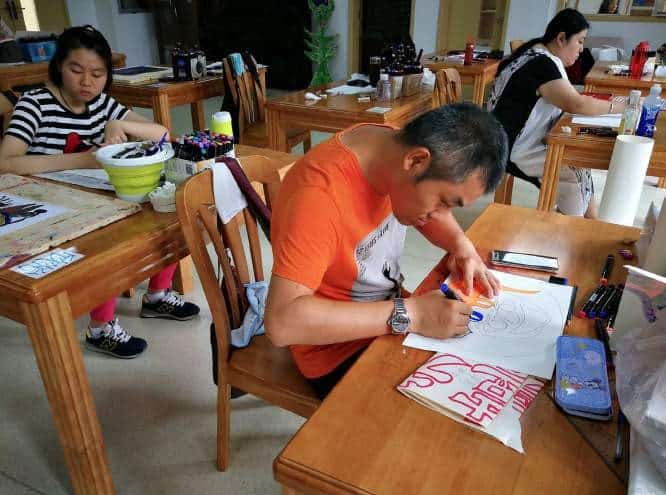

Benny Shaffer: I’d say the strongest parallels between the workshops are in their overarching missions, which can be seen in their philosophies of non-intervention; they don’t provide specific artistic training or formal instruction for the participants, and don’t intervene in the creative process. Instead, they provide an open space for free experimentation that allows the participants to develop their own distinct artistic practices and styles at their own pace. At the workshops in China and Japan, we were both struck by the extremely distinctive, and in many cases radically different approaches that the individual artists took in their practices. This came as a surprise because they often work in close proximity to one another over many years. While the participants of both workshops engage with one another in different ways in their communities, and the workshops create a space for social connection and shared experience, the individual experiences of all the participants vary dramatically.

SM: The exhibition was unique in that in addition to showing the art from the workshops in China and Japan, it also included a symposium involving scholars from Harvard and other institutions who explored the current state of disability and mental health services in China and Japan from the perspectives of law, anthropology, disability, and health services. Attention was given to the ways that the societies deal with stigma in families and communities. In the symposium there was unanimity with regard to how the art workshops can not only help the individual participants with the daily challenges they face, but also how they might further understanding within the various communities and regions of China and Japan.

Benny Shaffer: We wanted to engage a broad, interdisciplinary community of scholars and art practitioners, so it was essential for the exhibition to also have an academic symposium. We began planning this part of the exhibition-related events from the beginning. In Karen Thornber’s introduction to the symposium, she spoke to the urgency to support more scholarship on questions of disability and mental health, and to offer deeper insights into the scope and extent of these issues in East Asia. Raphael and I then talked about how it was crucial for us to contextualize and consider the social, cultural, and political dimensions of the workshops’ activities, and also show a clear focus on the processes and conditions of production at both art workshops.

Guo Haiping and Masato Yamashita then shared with us the history, guiding principles, daily practices, and future plans of their respective workshops. As I mentioned before, they both insisted on how they do not intervene in the creative processes of the artists and pointed out, based on their years of experience, how these artistic practices noticeably improved the quality of life of the people in the workshops, and helped fight widespread stigma toward people with mental disabilities and mental illness in their respective societies. The second panel focused more specifically on the social and legal issues associated with disability and mental illness in China and Japan. The first two speakers, William Alford (Director, Harvard Law School Project on Disability and Professor of Law) and Cui Fengming (Director, China Program, Harvard Law School Project on Disability, and Professor, Renmin University of China Law School), presented the work of the Harvard Law School Project on Disability, which works to improve the concrete living conditions of people with disabilities by working with and improving upon existing legal frameworks. Their work tackles legal issues to fight discrimination and unequal access to employment and education. Professor Cui offered the striking example of the Chinese college entrance exam (gaokao), which until recently did not provide any way to accommodate the needs of people with major visual impairment. The following speaker, Andrew Campana, began his talk with a bilingual performance of poems by one of the Japanese artists in the show, Ukai Yuichiro.

He also shared interdisciplinary insights into how activists for the rights of people with disabilities have produced artworks in a variety of media, ranging from poetry to performance, to make their voices heard in Japanese society. Finally, Arthur Kleinman (Professor of Anthropology, Professor of Medical Anthropology in Global Health and Social Medicine, and Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard University), reflected on his ethnographic fieldwork on mental health in China over the past three decades and the changing conditions. On the following day Raphael gave a presentation at the Harvard Art Museums’ Art Study Center on works from the collection related to mental health and self-taught art.

This above paragraphs are only part of the full text to be published on CAET Vol 5(1).