Ch’i and Artistic Expression

— An East Asian Worldview that Fits the Creative Process Everywhere

气和艺术性表达:契合所有创造性过程的东亚世界观

Shaun McNiff, Lesley University, USA

Abstract

In the tradition of ch’i (气 ), past and present, we have a paradigm that accurately corresponds with how artistic expression happens and heals through the circulation and transformation of creative energy. It is a thoroughly empirical approach to forces inherent in all of nature which include physical and psychic elements of creative action. Beginning with reflections on the qualities of ch’i and how it has been interpreted in the West, this article explores its presence and cultivation. The historic Taoist and Confucian emphasis on nurturing ch’i as a personal way of participating in the more comprehensive creative processes of nature offers a timely practical and conceptual model for how art heals.

Keywords

ch’i/qi, creative force, creative energy, wu-wei, te/de, authentic expression, art as a force of nature, neidan, art alchemy

摘要

在“气”的自古至今的传统中,我们有一个范式精确地回应艺术表现如何通过创造性能量的循环和转变进而发生并进行疗愈的。 它是一种对所有自然固有力量彻底的实证方法,包括创造性行为的身体和心理上的因素。 从对“气”的质地及其在西方的解释的反思开始,本文探讨了它的存在和发展。历史上的道教和儒家强调培养“气”作为更为全面地参与自然创造过程的个人方式,为艺术如何疗愈提供了及时的实用性和概念性模型。

关键词

气,创造力,创造性能量,无为,德,真实表达,艺术作为自然力量,内丹,艺术炼金术

What is ch’i and how does it relate to artistic expression and soul?

The idea of ch’i as a real, empirical, and creative force moving through all of life aligns with my experience of the process of artistic expression—how art happens and how it heals.

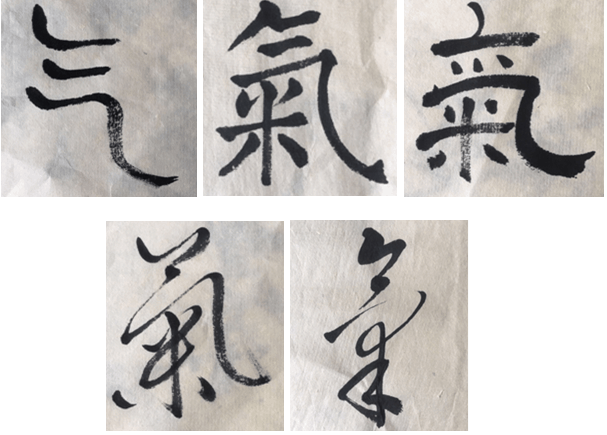

Ch’i (also called qi— gi in Korea and ki in Japan) is described as the material force by Chan Tsai, 1020-1077 (Chan, 2008; Tucker, 1998; Ekken, 2007). Mencius (Mengzi), c. 372-289 BCE, in one of the earliest recorded reflections on ch’i, called it the passion-nature and approached it as something to be nourished (Legge, 1861, p. 43). Throughout Chinese and Asian history ch’i has also been interpreted as the vital force, vital energy, vital power, moving power, breath (Wei-Ming, 1993; Yun, 2012), and psychophysical energy (Yun, 2012; Lee, 2014).

My sense is that in East Asia and beyond there is general agreement as to the nature of ch’i as a force that is both physical and psychic and integral to all forms of life. Many of us in the West view soul in a closely related way, as the distinctive energy and character of an expression, being, or entity. Both ch’i and this sense of soul are antithetical to the pervasive idea in the West that soul is separate from the body.

James Hillman approaches soul as a deliberately indefinite term that involves a way of looking at things, a deepening of perception, rather than as a particular entity. This sense of soul cannot be separated from the context in which it is experienced (1975, p. x). The same may be said about ch’i which is consistently viewed as an empirical force and arguably does not carry the extensive religious attributions historically associated with the prevailing Western notion of soul. Hillman’s commitment to keeping the openness and imagination of soul can benefit our reflections on ch’i, sustaining its inherent fluidity and change and guarding against the tendency to solidify it conceptually and establish fixed methods of engagement. In reflecting on the tradition of ch’i in East Asia, Tu Wei-Ming similarly described how the fluid and inclusive nature of the idea and the absence of an exact definition has furthered the imagination of it (1993, p. 37).

Pairing ch’i and the earthly sense of soul can complement both. The former in my view suggests the physical nature of how vital and soul processes move and circulate, arouse and inspire, and constantly transform and change experience and consciousness. It gives body and physicality. And the latter infuses imagination into our reflections on ch’i, keeping the change and creative flow informing its original Taoist conception. It helps to assure that the psychic and creative aspects of ch’i are not forsaken.

Ch’i will be approached here as a creative force that permeates all of life and manifests itself in infinite forms. This is perhaps consistent with Chang Tsai’s (1020-1077) sense of it being one material force as contrasted to how other traditions have divided it into two principles (yin and yang) and five agents (metal, wood, water, fire, and earth), all of which Chang Tsai viewed as aspects of ch’i (Chan, 2008, p. 495). As with any essential human condition, China has no doubt generated many different interpretations of the fundamental force of ch’i and practical methods for engaging it ranging from the encouragement of authentic and spontaneous expression to more complex, technical, and systematic practices such as the contemplative and medical applications of qigong. The idea of an elemental and soulful creative force resounds with everything I do.

In the Confucian tradition there is an emphasis on the cultivation of ch’i energy in moral and spiritual practices conducted in relationship to the forces and rhythms of nature. I encourage adding creative expression as a third element, with all three participating in a comprehensive cultivation of life-affirming and transformative energy that enhances personal well-being and the environments that sustain us.

Empirical artistic activity suggests the basis of ch’i

In keeping with the psycho-physical nature of ch’i, I will concentrate on the material qualities of artistic actions and their effects; how particular acts of expression–the movements of a brush, body, voice—manifest creative energy. Experience shows that art ch’i takes many different forms and moves in endlessly varied ways with each gesture having its distinct qualities and impacts. Informed by the work of my mentor Rudolf Arnheim (1954), I have also explored the energetic expression of artworks themselves as in my 1993 essay dealing with the vitality and aliveness of objects and images and not just the physical act of making them. Tangible creative energy permeates both process and product as interdependent partners in artistic expression.

My vantage point for reflecting on ch’i is my own firsthand experience in making art alone and with others, an approach that I have called art-based research (1998a, 2013). Rather than beginning with the concept of ch’i, my efforts to understand the forces moving though the artistic process led me to it and an appreciation of how it articulates what I experience with artistic expression.

The way connections to ch’i have grown from my empirical art practice can be likened to how the process philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead established congruence with Chinese thought. Whitehead’s inquiry within the Western philosophical and scientific tradition generated a view of actuality as comprised of momentary events that are connected to a more comprehensive creative force in all of life (1970). In trying to understand the art experience, I have stayed immersed in the artistic actions and expressions trusting that they will generate outcomes that, in keeping with the nature of the creative process, cannot be known in advance.

I must offer a word of caution in relation to everything I am saying about art and ch’i. I am not calling for a new system of arts therapy ch’i practice, a position that is consistent with is consistent with the early Taoist realization that spontaneous actions and reflections in their infinite range are preferred to operating according to a doctrine. The continuous doing of artistic expression and reflection upon it must always take precedence over any attempt to describe or explain it, including ch’i.

A transformative force of nature and wu-wei

In my artistic practice and when helping others express themselves artistically, I have experienced creative expression in all media as a force of nature (McNiff, 2015). Approaching artistic actions as universally accessible to all of us, like breathing and moving, is for me the best way to support more egalitarian participation. When inviting people to become involved, I emphasize the movement basis of every form of creative expression and try to strengthen their commitment to simply moving in authentic and natural ways, always encouraging spontaneity and the relaxation of resistance, control, and too much thinking.

If we start with the assumption that ch’i is universally present, the work of artistic expression is framed as activating and cultivating a creative energy that we already have, something that may be dormant or blocked. There is no need to be anything other than what we are and thus every person can engage in significant expression. The orientation shifts from the impossible task of meeting an external and idealized conceptual standard to manifesting one’s unique being and engaging what happens. Similarly in classical Chinese painting the purpose is not exact representation of nature but the expression of the artist’s unique person and style as a manifestation of nature (Mackenzie, 2008).

If ch’i is to be approached as the life force encompassing the most complete range of human expression, then all possible types and qualities of action have a place within the spectrum of expression–—dark and light, tense and relaxed, rough and smooth, aggressive and calm, choppy and fluid, orderly and chaotic, and various combinations of these and other qualities. I feel that the common tendency to encourage only harmonious, comforting, and carefully controlled and orchestrated expressions limits the full spectrum of creative energy. If we are creating as a force of nature, wild expressions must have their place too.

The transformation of negative and strong emotions and gestures through artistic expression will often generate the satisfaction, calm, and well-being that we may ultimately seek. Additionally, the whole range of potential expressive gestures and emotions are participants in an interdependent whole, the eco-relations of creation. We cannot assume that one kind is more desired than another.

In my experience we create from wherever we are and the challenge is to simply start to move realizing that the end cannot be known at the beginning. The goal is generally one of making a commitment, sustaining movement, and staying involved. Of course there tend to be many resistances and conflicts whenever people are given opportunities to become involved in artistic expression. Rather than trying to fight or eliminate resistance, I encourage the embrace of it as natural, part of nature. I resist all of the time. Resistance in this respect can take the form of ordinary existential ennui and habit. The most mundane things in my experience tend to challenge me the most, getting myself to the studio, and beginning a new body of work that builds upon itself and generates energy. Resistance can also take the form of intense fears and vulnerabilities, all of which I have come to embrace as necessary yeast for the process and the fuel of creative expression.

Although I do not encourage arbitrary concentration on particular kinds of movement, I always emphasize the significance of simple and natural gestures and repetitions, again reinforcing the significance of breath and elemental processes accessible to all. Movements will naturally vary themselves so we try to stay with an essential movement, become immersed in it, allow “it” to vary itself rather than become too controlling and cerebral about what is happening. Whenever we begin to think too much, the spontaneous flow and intelligence of the process is lost.

I try to be receptive to whatever is active in me at the time. Therefore, nothing is ever set as a pre-condition of action and beginning. I just start to work and do my best to respond to the endlessly variable conditions of the present moment where there is always something happening and moving, often outside awareness and again this affirms the importance of simply starting to move as naturally as possible, trusting and knowing from experience that things emerge from gestures, that the most important new things often happen contrary to intentions, that artistic expressions generally take shape in response to whatever is done in a particular moment, and that in order to help this process along I simply need to begin and keep working. What I am trying to describe here can be viewed as a practical process of activating the circulation of ch’i in sync with the endless variability and uniqueness of personal gestures which can be considered a defining feature of the artistic process. This contrasts to the various approaches to stimulating the circulation of ch’i through relatively fixed and consistent movements and exercises that are repeated by people.

Taoist tradition offers guidance on how to enhance the optimal flow of ch’i through the practice of wu-wei (无为 ), widely described as “non-action.” I feel that this interpretation is a subtle and paradoxical guide to action rather than a literal encouragement to avoid acting altogether. Chuang Tzu, 370-287, BCE, makes this explicit in saying how non-action is action rather than in-action. It is unstudied and emerging from “stillness” (Merton, 1969, p. 80). Wu-wei encourages a particular way of acting. Edward Slingerland affirms the metaphoric nature of wu-wei in describing it as “effortless action” (2003). Lao-Tze in the Tao Te Ching (道德经 ) says that wu-wei is innate and authentic (te/de德 ) action in accordance with the movements of nature, an approach that carries within itself a timeless guide to well-being as I discuss later. Although te is often translated into English as virtue it also suggests a person’s innate character and power which corresponds to what I call authentic expression.

When starting to create I might have a sense of what I would like to do but I have learned repeatedly that the expression always emerges through the unplanned movements and gestures of the process. What I have learned through experience is consistent with the original Taoist realization that the willful mind and its controlled actions block access to what happens beyond its dominion and obstruct the flow of the Tao (ch’i). Within this nature-based paradigm of expression, the individual will (ego) and expectations are not the exclusive determinants of action. When I approach expression as a force of nature, I am not a passive instrument through which it acts. I cooperate with it. Reciprocity is essential as with the more comprehensive interdependence of life processes.

The creative process is an intelligence that tends to be a step or two ahead of the reflecting mind and we interrupt it with our controls. If we trust it, and let go of excessive controls, it will take us where we need to go. I have likened this to how the vital circulation of ch’i will find its way to the blocked energy.

My practice in helping others with artistic expression happens almost exclusively in group studio sessions because communal participation in my experience fosters a collective ch’i that supports individual expression. Of course groups can also intimidate and suppress creative energy, thus leadership is required to assure that a positive creative contagion is cultivated. I find that the group augments creative energy in that it is composed of many different forces and participants that can merge together into a common flow that carries everyone in it. I have called this the creative slipstream effect (2003, pp. 37-54). In my own experience, simply being required to be present during the group sessions helps me access artistic ch’i. I have likened the studio sessions to retreats where we leave our regular and habitual daily lives and enter a creative space that acts upon us. I experience this happening in subtle and indirect ways. When the optimum conditions are realized, the environment vibrates creative energy that is heightened by the group and transmitted to individual participants.

As someone who spends most of his creative time working alone, I nevertheless find the group retreats essential. They are a community of creation, an immersion in human nature, that connects me quite literally to forces beyond myself that inspire, activate, and draw me into complete engagement with artistic expression. Participants affirm how this happens for them too. There are many things that we do to establish what I call a creative space but the most fundamental aspects involve the process of pursuing natural creative expression in the company of others who witness and affirm rather judge.

Moving and working together invariably heightens the environmental and internal ch’i. Rather than introducing concepts of any kind we use percussion, rhythm, and repetition to relax the mind and this invariably furthers wu-wei where the action emerges more naturally from bodily gestures. Critical response is an important element within the total process of creating but we all tend to need an affirming environment where we can express ourselves naturally and allow the movements and creative acts to realize their inherent potential.

Quality

Quality and skill are not antithetical to wu-wei. We know from any expressive discipline that trying too hard and extreme mental effort, what I call white knuckle control, blocks more fluid gestures and thus restricts the realization of potential. Once the process of expression is moving, it has an intelligence within itself (1998b, 2015). Again, the tradition of ch’i affirms the need to cultivate a vital energy circulation which finds its way rather than being directed by the mind. This is particularly relevant to complex problems often inaccessible to linear solutions and more amenable to creative transformation.

I find that when the ch’i is circulating with full vitality, it carries a perfecting process within itself. We simply need to establish the conditions for the natural elements to do their work. The most inclusive approach to artistic expression as a force of nature within every person does not oppose or contradict the refinement of skill and committed practice which enhance wu-wei. As in nature we are all in different places with regard to practice and the common feature is authentic expression and the cultivation of ch’i. When asked if this authentic and spontaneous expression is potentially manifested in all of life, I say yes. Since ch’i is the vital force of nature and what I describe here as creative energy, it is potentially present in each moment of art-making as well as the most common daily experiences, like breath, all of which contribute to a self-generating life process.

In my view, there is no hierarchy of ch’i in art and life; no differentiation between high and low forms, only the endless appreciation of the unique qualities of particular life moments. As Tu Wei-Ming emphasizes (1993), the three primary East Asian traditions of thought (Taoist, Confucian, and Ch’an Buddhist) share a worldview where all aspects of life participate in a continuous and reciprocal process of creative transformation. What is unique to this perspective is its consistent commitment to the creative transformation of the person as well as the particular artistic expression, something that has significant relevance to the arts in education and therapy.

Of course disciplines of artistic practice in both the East and West have many distinct dimensions of skill, craft, aesthetic form, and aspirations for quality. My purpose here is not to reduce all of artistic expression to an undifferentiated and amorphous energy of ch’i. Each gesture of art carries within itself a complete uniqueness within the moment of its emergence, just as in the process of nature. Artistic expressions are informed by an inherent tendency for quality and the most complete realization of themselves. This applies to all phases of expression from the initial action to the process of shaping, re-working, revising, and ongoing practice and preparation with every act and moment aspiring for the most fluid manifestation of wu-wei.

As an advocate for universal access to artistic expression I believe that each artist, and every person willing to participate, may strive for the most complete and effective expression in relation to nuances of personal experience and skill. Chinese and East Asian ideas about ch’i offer a framework for holding all of these elements where quality involves meeting the specific and distinct conditions of life situations.

Transcultural and eco implications

These reflections on ch’i are consistent with my more general effort to stay grounded in practice within a particular place and then try to understand what happens in relation to history and the experiences of others world-wide. My bias is informed by an ever increasing sense of wonder in response to what I perceive as a common human community expressing infinite and ever-changing differences, a view that perhaps corresponds to Chang Tsai’s view of the ch’i permeating all of life with many different characteristics and manifestations. The infinite variability of life participates in a common creative process that steps outside the binary concepts of universality and difference while holding them both.

Anything of depth and sustained value must in my view be connected to things beyond itself. No thing is exclusive to itself. For example, when I discovered how indigenous communities throughout the world, including pre-Taoist China and its neighbors, consistently approached illness as a loss of soul, I felt that this idea originating in distant times and places precisely expressed what I experienced in my arts therapy practice. Through ritual enactment with the support of the community the healer or shaman went in search of the lost or abducted soul and restored it to the body. I described how each of us can take on this restoration of lost soul through the mediation of artistic expression vs. reliance on a literal shaman (1979; 1981, pp. 3-28; 1992, pp. 16-26; 2004, pp. 181-208).

From a ch’i perspective the lost soul can be viewed as the lost flow of creative energy. The blockage and ills stemming from the loss, are transformed by re-activating vital circulation. Toxins, obstacles, and difficulties participate as fuel for what I call art alchemy (1981, p. 224; 1992, pp. 35-36) which interestingly enough has a corresponding name in the Taoist principle of neidan (内丹 ), inner alchemy. The process is in my view indigenous to the human condition. It is the basis of healing and essential to the eco-relations that shape us all.

Ch’i, wu-wei, soul loss, neidan, and other processes described here are all manifestations of the movements of nature on micro and macro levels where no thing or being is separate from the larger creative process. Seeing ourselves as contributors to an all-inclusive creative force both inside and beyond ourselves, is for me the medicine the world needs.

About the author

Shaun McNiff, University Professor, Lesley University, Cambridge, MA, USA. Email: smcniff@lesley.edu

References

- Arnheim, R. (1954). Art and visual perception: A psychology of the creative eye. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Chan, W. T. (2008). A source book in Chinese philosophy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [originally published in 1969].

- Ekken, K. (2007). The philosophy of qi: The record of great doubts, (M. E. Tucker, Trans.). New York: Columbia University Press.

- Hillman, J. (1975). Re-visioning psychology. New York: Harper and Row.

- Lee. H. D. (2014) Spirit, qi, and the multitude: A comparative theology for the democracy of creation. New York: Fordham University Press.

- Legge, J. (1861). The Chinese classics, volume II, the works of Mencius. London: Trübner & Co.

- Levine, S. (2015). The Tao of poiesis: Expressive arts therapy and Taoist philosophy. Creative Arts Education and Therapy: Eastern and Western Perspectives, (1) 1, 15-25.

- Mackenzie, C. (2008). Artists & ancestors: Masterworks of Chinese classical painting and ancient ritual bronzes. Middlebury, VT: Middlebury College Art Museum.

- McNiff, S. (1979). From shamanism to art therapy. Art Psychotherapy, 6 (3), 155-161.

- McNiff, S. (1981). The arts and psychotherapy. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas.

- McNiff, S. (1992). Art as medicine: Creating a therapy of the imagination. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

- McNiff, S. (1993). The authority of experience. The Arts in Psychotherapy, (20), 3-9.

- McNiff, S. (1998a). Art-based research. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- McNiff, S. (1998b). Trust the process: An artist’s guide to letting go. Boston: Shambhala, Publications.

- McNiff, S. (2003). Creating with others: The practice of imagination in art, life and the workplace. Boston: Shambhala Publications.

- McNiff, S. (2004). Art heals: How creativity cures the soul. Boston: Shambhala Publications.

- McNiff, S. (2013). Art as research: Opportunities and challenges. Bristol, UK: Intellect & Chicago, USA: University of Chicago Press.

- McNiff, S. (2015). Imagination in action: Secrets for unleashing creative expression. Boston: Shambhala Publications.

- McNiff, S. (2015). A China focus on the arts and human understanding. Creative Arts Education and Therapy: Eastern and Western Perspectives, (1) 1, 6-14.

- Merton, T. (1969). The way of Chuang Tzu. New York: New Directions.

- Slingerland, E. (2003). Effortless action: Wu-wei as conceptual metaphor and spiritual ideal in early China. NY: Oxford University Press.

- Tucker, M. E. (1998). The philosophy of ch’i as an ecological cosmology. In M. E. Tucker and J. Berthrong (Eds.), Confucianism and ecology: The interrelation of heaven, earth, and humans (pp. 187-207). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Center for the Study of World Religions & Harvard University Press.

- Wei-Ming, T. (1993). Confucian thought: Selfhood as creative transformation. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Whitehead, A. N. (1978). Process and reality: An essay in cosmology. New York: Free Press.

- Yun, K. D. (2012). The holy spirit and ch’i (qi): A chiological approach to pneumatology (Princeton Theological Monograph Series 180). Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications.