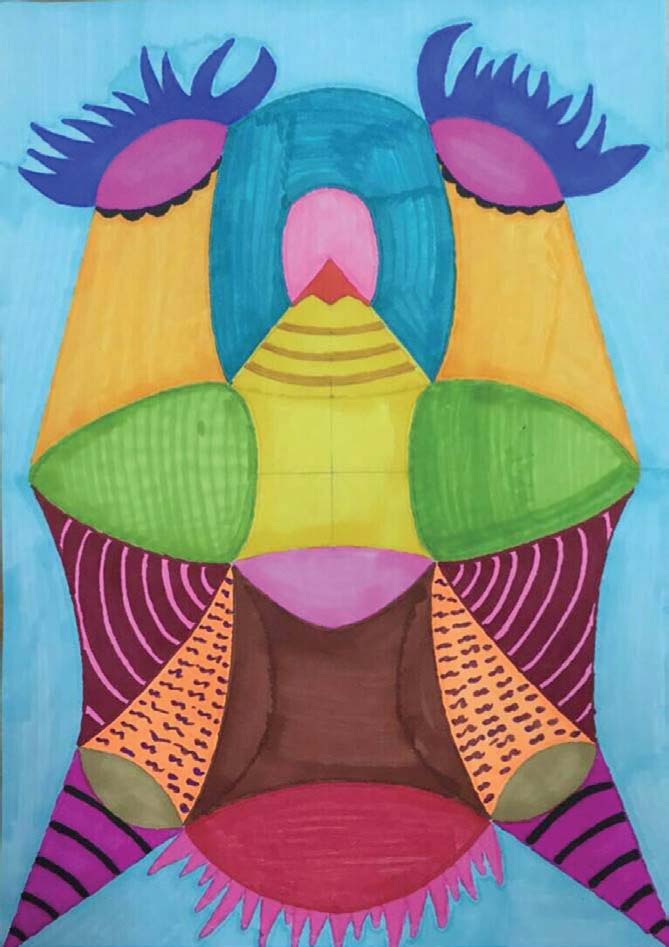

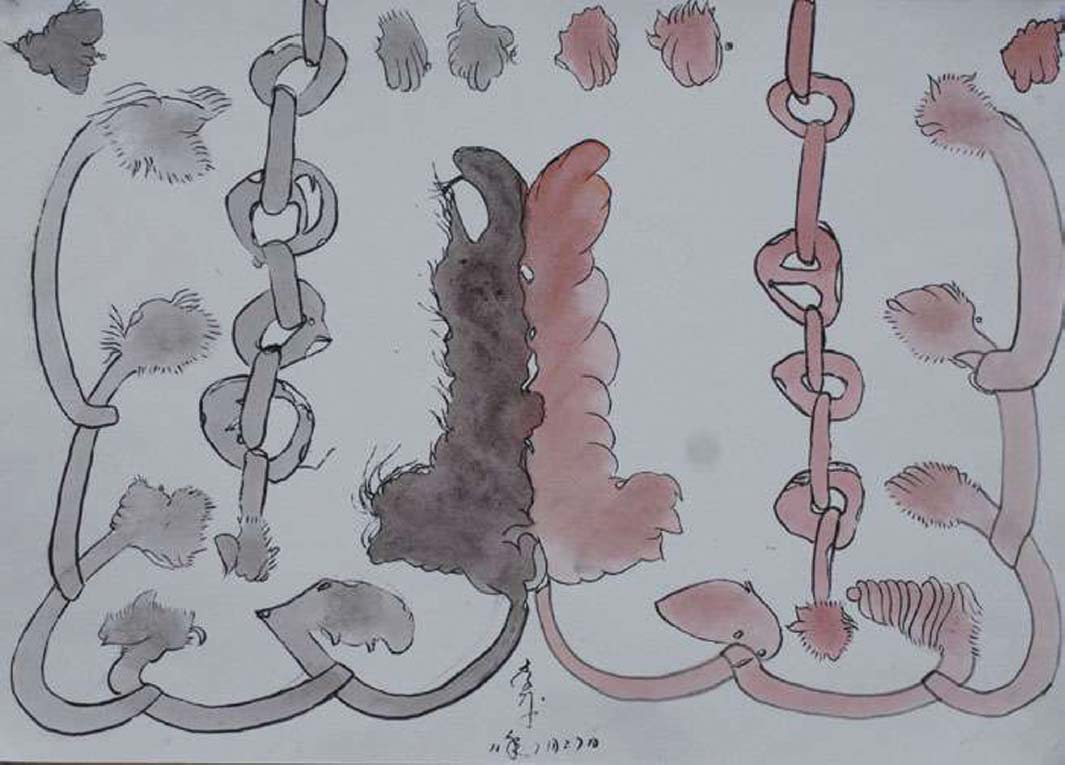

FIGURE 1 | Wang Jun: Three Mountains, marker pen on paper, 78x54cm

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2018) 4(1):10–25 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2018/4/3 |

Outsider Art in China—An Interview with Guo Haiping

中国原生艺术—郭海平访谈

Nanjing Outsider Art Studio, China

Chen Shushan: Can you tell our readers about your personal history and how you became involved with art, psychology, mental health and art therapy?

Guo Haiping: I was born in Nanjing in 1962. That year marked the end of China’s three years of natural disasters during which time (according to the official figures) 37.5 million people starved to death. I probably would not have survived had I been born one or two years earlier. When I was four years old, China began the decade of “Cultural Revolution,” the so-called “ten years of catastrophe.” Mao Zedong – a figure of almost godlike importance in that era – encouraged people to rebel. His Selected Works was the most frequently read text during my primary and middle school years and the slogan “Do not forget the class struggle” was painted in all the streets. In 1979 I dropped out of school before graduation and became a factory worker. In retrospect, I cannot say with certainty whether my dropping out was a manifestation of a rebellious spirit, although I soon began to feel an unprecedented irritability. At this time I also met several young artists. Despite the fact that I had never heard of the concept of "art," I was attracted to these people at first sight – and to what they did. Soon I followed them in making sketches and paintings and I began to read books introducing me to Van Gogh, Gauguin and several other artists; one of these books was Van Gogh’s diary, Lust for Life.

In reading this book, I saw how great changes could take place within those who devoted themselves to art. I was inspired and became pretty overwhelmed with excitement. I decided that, within a period of two years, I would resign from the factory and become a freelance artist. Forty years ago in China, choosing to become a freelance artist could be life-threatening for only state-owned units could make money. Firmly against my parents’ wishes, I tried to flee the country but I failed. My longing for freedom, however, only became even more intense. While trying to relieve my existential burden, I accidentally turned to psychology – a subject rarely read in the 1980s. Abnormal psychology was not included as a subject for study in the university – neither was it used to understand the people who were confined in what were then called lunatic asylums. I could rely on no one but myself to achieve self-salvation and understanding by undertaking this study on my own.

In 1989, the head of the Communist Youth League in Nanjing learned about psychological counseling in Hong Kong and planned to provide this service to young people in Nanjing. He could not, however, find qualified people in either Nanjing’s universities or in the asylum. It was at this point that he accidently read my psychological articles in the Nanjing Daily. I was working as a graphic designer in a printing factory at the time. The head of the League made an appointment with me and persuaded me to do psychological counseling work. He had originally planned to first undertake a market study to assess the need for such counseling, but he was overwhelmed by responses from young people searching for psychological support and help. I guess the need was clear. With his help, I left the printing factory and became engaged with the newly established Nanjing Youth Psychological Counseling Service Center. Since I was primarily interested in the relationship between art and psychology, an art department was set up in the center. I could not find any art therapy books or relevant information at that time, so I encountered many difficulties during this initial process of self-study. I left the service center after four years and some two years later it eventually went out of existence. I was exposed to a broad spectrum of mental illnesses during my four years there and I explored the role of art in dealing with a number of psychological problems.

Chen Shushan: You said that you have been devoted to promoting the development of outsider art. Our readers are very curious about your reasons for doing this?

Guo Haiping: After leaving the Psychological Counseling Center, I started running a cafe with my wife; we catered to pioneering artists and our café was where a number of experimental art activities were held. Public interaction and the role that art played in relation to people and society were emphasized. These activities, however, failed to live up to my expectations. Some six years later, I transferred the ownership of the cafe to another artist and decided to become a freelance artist. In 2005, I was the curator of an exhibition named “Sickness” in Nanjing’s Art Gallery myself. I was convinced that the occurrence of a variety of psychological problems was related to the varying conditions of our social environment. During the exhibition, it occurred to me that I could start learning about art works made by asylum-based patients with mental illnesses. I shared this idea with a patron. He unexpectedly agreed to sponsor me and expressed his willingness to help me to find a mental hospital in Nanjing that would cooperate with me. On October 10th, 2006, I began three months of exploration and practice in Nanjing Zutangshan Mental Hospital.

Chen Shushan: Can you describe the first art works that you saw in the mental hospital that had an impact on you?

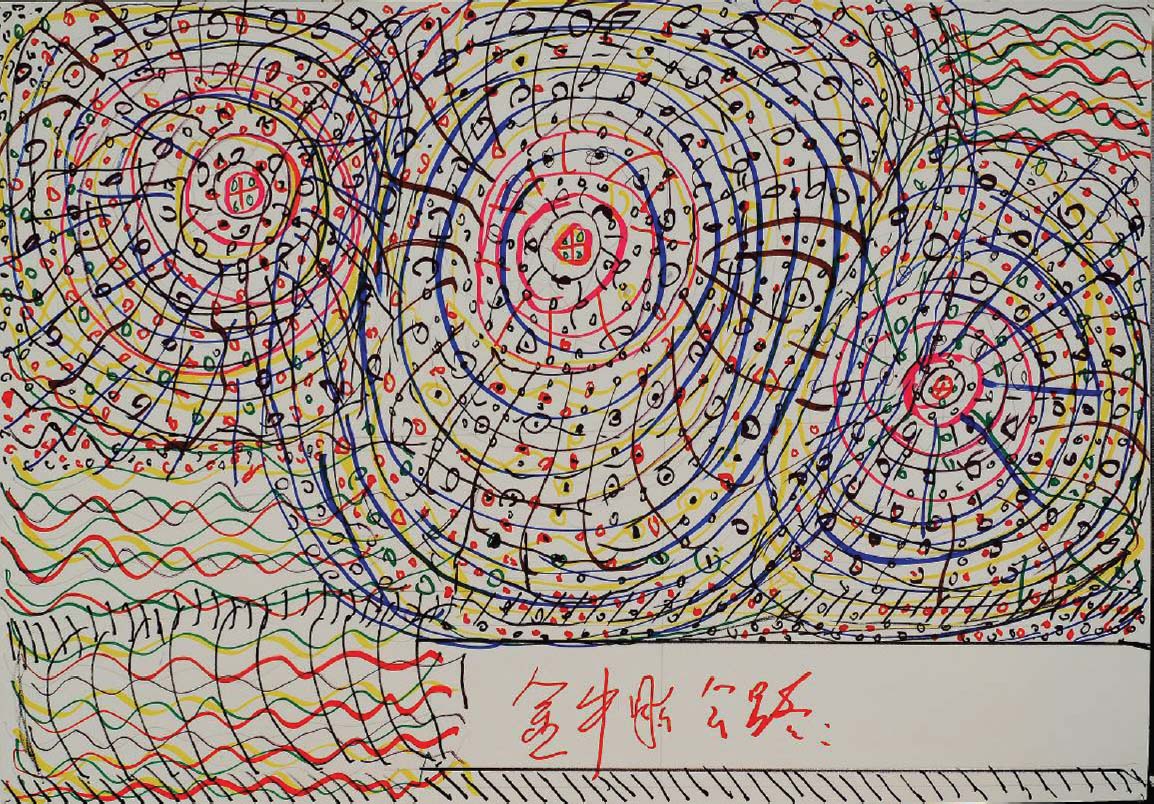

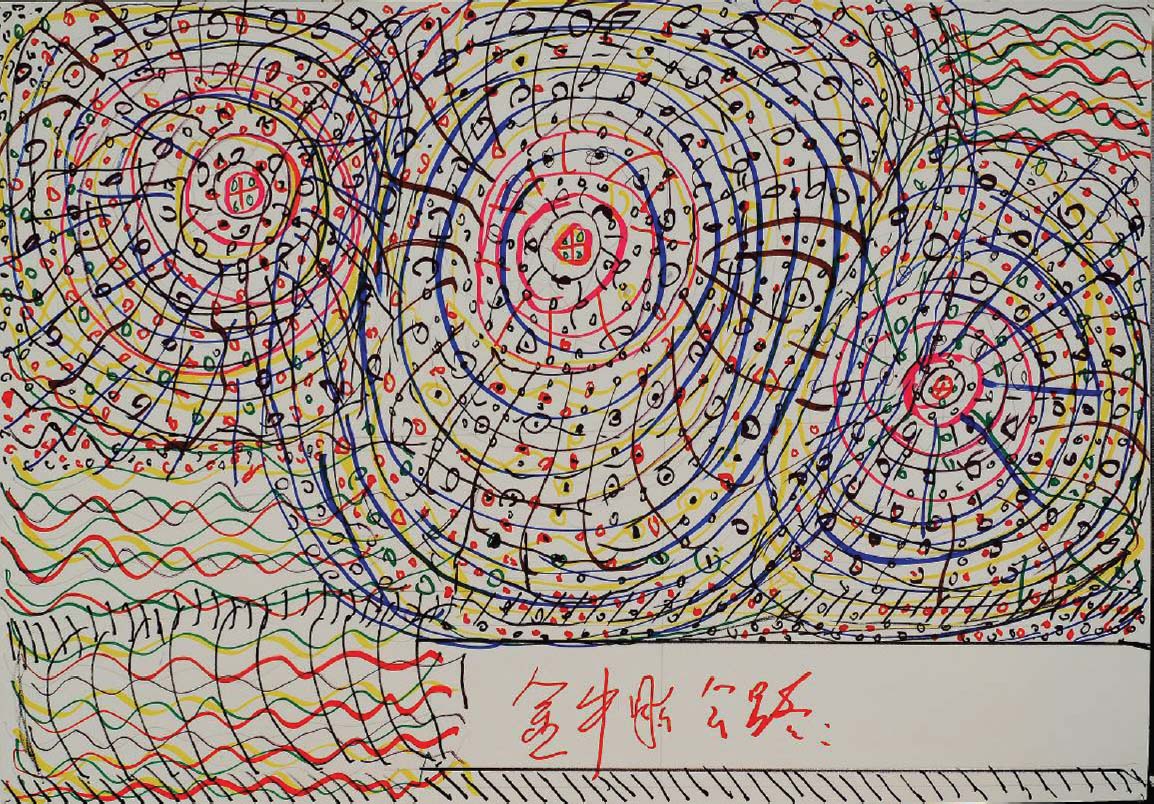

Guo Haiping: The paintings made by a peasant named Wang Jun (b. 1957 in Nanjing) impressed me most. When I first saw Three Mountains I did not understand it. He told me that it was an image of three mountains near his house but I still could not see this. When I continued to inquire about the picture, he told me that he painted it as a bird’s-eye view, just like the perspective of a map. I asked if he had ever flown in a plane? He said. “No.” I then felt that he was perhaps expressing an out-of-body experience. His perceptions – like those of other outsider artists within mental health settings – are very free and flexible. In addition to this bird’s-eye perspective, he also includes what are called X-ray views that look inside objects. This appears in his other works. In his painting Tractor, he combines several different perspectives in one work. I subsequently found that many other works painted by patients used exactly the same methods. Two or three years later I would discover how these ways of painting were present in the works of indigenous artists – especially in the art of Australian aborigines. Such free and flexible views often appeared in the ancient images that our ancestors created and this suggested to me that ways of perceiving the world (sometimes attributed to mental illness) are often manifestations of what we might call psychic or artistic atavism.

FIGURE 1 | Wang Jun: Three Mountains, marker pen on paper, 78x54cm

FIGURE 2 | Wang Jun: Tractor, marker pen on paper, 52x38cm

Chen Shushan: You mentioned that outsider art also includes the work of artists without mental disorders. Can you elaborate on this point?

Guo Haiping: We should be clear about definitions of both outsider art and mental disorders before answering this question. The two terms are very different and should not be confused with one another. Outsider art not only reflects a spirit of humanity but also the expression of the divine and of Nature. Illness is not an advantage for artists creating within mental health institutions. As I have said, outsider art also includes the work of artists without mental disorders. That means the outsider artist is not restricted to either a certain group of people or a specific cultural system or the constraints that would normally devalue the artistic expression and replace it with conceptual explanations and stereotypic ideas. I encouraged approaching the art for what it was – a manifestation of the human spirit without the constraints of concepts. I longed to simply experience and feel its expression, its presence and the impact it had both on me and upon others who reflected on it.

Chen Shushan: Are you familiar with outsider art research around the globe? Can you see similarities and differences with reference to Chinese outsider art?

Guo Haiping: In 2014, I published a book called Notes of Outsider Art in China where I reflected on exactly these issues. My insight into these questions has continued to develop and grow during the past few years. I am currently discussing an exhibition of work in China with Thomas Röske, curator of the Prinzhorn Museum at the University of Heidelberg.

I see significant differences in how people from both China and Europe respond to outsider art. For the past two thousand years, China’s culture has been defined as secular and systematic – deeply rooted in the spirit of the Chinese people and mainly reflected in the worship of and dependence upon secular power. Once deprived of such power, people tend to experience a sense of insecurity and even horror. Since ancient times, the power of the supernatural has been demonized in China. The mythological emperor Zhuanxu cut off the passageway between heaven and earth to reinforce social hierarchy and to establish a sense of control. People tend to approach this subject area with a high degree of vigilance and maintain a “safe” distance. To the extent that outsider art is viewed as a manifestation of these forces, it becomes an obstacle to engagement. People in Europe – perhaps influenced and shaped by artistic movements ranging from the Renaissance to romanticism, surrealism and expressionism – tend to open their arms to various forms of art. The major difference between people in China and those in Europe involves the public acceptance of outsider art.

As for the similarities – after careful observation it’s clear that basic characteristics of the outsider art spirit are highly consistent. Setting aside the origins of country and people, these similarities include the natural movement of the artists’ gestures, the use of color, the methods of perspective (mentioned earlier) and the basic desire for expression and aspirations for life to name just a few. Such similarities suggest that outsider art not only transcends the boundaries of country and nationality but also those of time and space. I believe that such an artistic language should be understood by all human beings; it is a shared expression that is able to shatter various cultural obstacles with its common understanding.

If we compare contemporary outsider art of China and Europe, it is possible to find some differences in the degree of performance, the making and showing of such art and the extent to which possibilities for the full realization of potential exist in each of the respective societies. While the performance aspect of European works may be fully demonstrated, Chinese works are faced with more obstacles in the realization of their promise. Despite these restrictions, however, an increasing number of Chinese people are now appreciating possible future developments of outsider art. Perhaps we can now contribute new ideas that are currently beyond the understanding of our European counterparts – for even though outsider artworks share universal qualities there are also individual influences from a region’s particular cultural ecology and historical background which affect each artwork.

Chen Shushan: Since the establishment of your Nanjing Outsider Art Studio ten years ago, work has been undertaken within both mental health institutions and local communities. What similarities and differences have you noted in these practices?

Guo Haiping: China’s mental health institutions are operated within a comparatively closed system. If hospitalized, a patient can only be discharged from that hospital under the guardianship of family members. Most of the guardians feel reluctant to take patients out of the hospital – even after rehabilitation – because there are numerous social problems relating to each patient’s acceptance, marriage, employment and public contact in general. Additionally, if the patient’s emotional problems become active again, there is a real lack of community health care services. Due to long-term isolation while they have been hospitalized, many patients suffer chronic deficiencies and impairments in both their mental and physical functioning; this can impair their overall potential for expression. Good mental and physical conditions and the freedom provided by the art studio enable the patients to be more fully expressive.

Since outsider art works are created in a closed environment, the patients who produce them are rarely subjected to external interference. In this regard, these works demonstrate authentic spiritual and visionary states and this art gives the public an opportunity to appreciate and understand the experience and expressions of people living in hospitals. The art offers evidence both of their humanity and their creative imagination. The connections made are emotional, sensory and direct and are not dependent on either language or explanation. Art produced in such a way can make people everywhere more aware of the creative and vital dimensions of life and the human condition.

Studios located in the community are quite different. Here the artists tend to have recovered in significant ways as compared to those who are isolated in mental hospitals and their more effectively expressive techniques are reflected in their art works. With their spiritual strengths enhanced in such a way, these artists sometimes become more demanding and active within their own communities. The problem, however, is that society fails to provide the proper facilities and services to meet their needs; there is an assumption that these artists should keep silent while they are isolated in the hospitals and houses within their local communities. Addressing these problems, therefore, is clearly going to be a long-term and complex social undertaking. We are working to provide a suitable cultural and ecological environment for these outsider artists by establishing a semi-enclosed community as a transitional space. The studio within this transitional setting offers structure and support but also encourages contact with the surrounding community.

Chen Shushan: Why was this studio project offered within the community instead of being based in a mental hospital?

Guo Haiping: In 2006, when we began negotiating with staff at the mental hospital on this issue, they were unable to understand the importance of the outsider art project. Additionally, it took ten months of communication to reach agreement. Although the hospital staff did ultimately realize the significance of the project, they were still reluctant to pioneer a controversial social experiment that would publicly talk about what were then sensitive social issues regarding mental health. In order for us to implement this project, it was necessary to transfer it into the community. Some seven or eight years later, hospitals would become interested in establishing art studios – by that time, however, these projects had been developed extensively across various communities and we did not have additional resources to expand them any further.

Such a change in attitude was primarily aimed at solving the hospital discharge issue – a key problem connected to a limited number of hospital vacancies that were common throughout China. The hospitals’ wish was to establish channels that would allow patients to return to the community. Compared to the position they had held a decade before, the government was gradually coming around to accepting this concept – but the public was still not ready to embrace these patients and their work. The outsider art project wanted to make an aesthetic contribution in order to help society understand and accept people with mental health challenges.

Chen Shushan: Can you introduce and show some artworks from your studio?

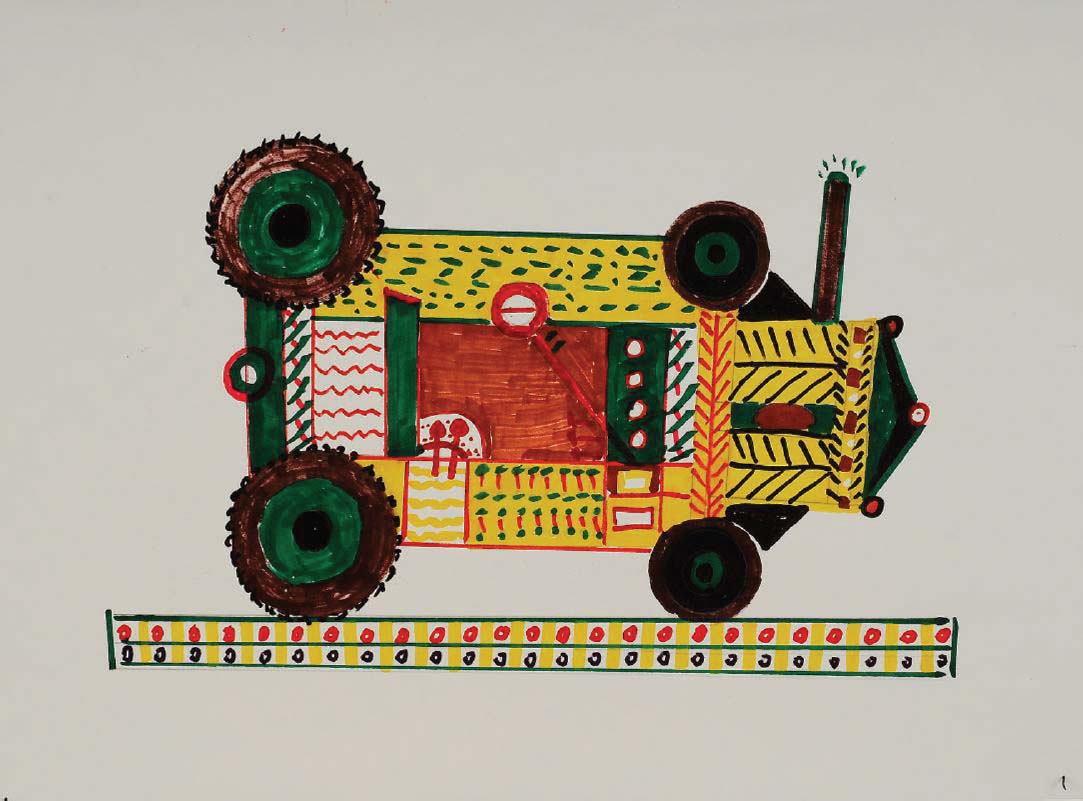

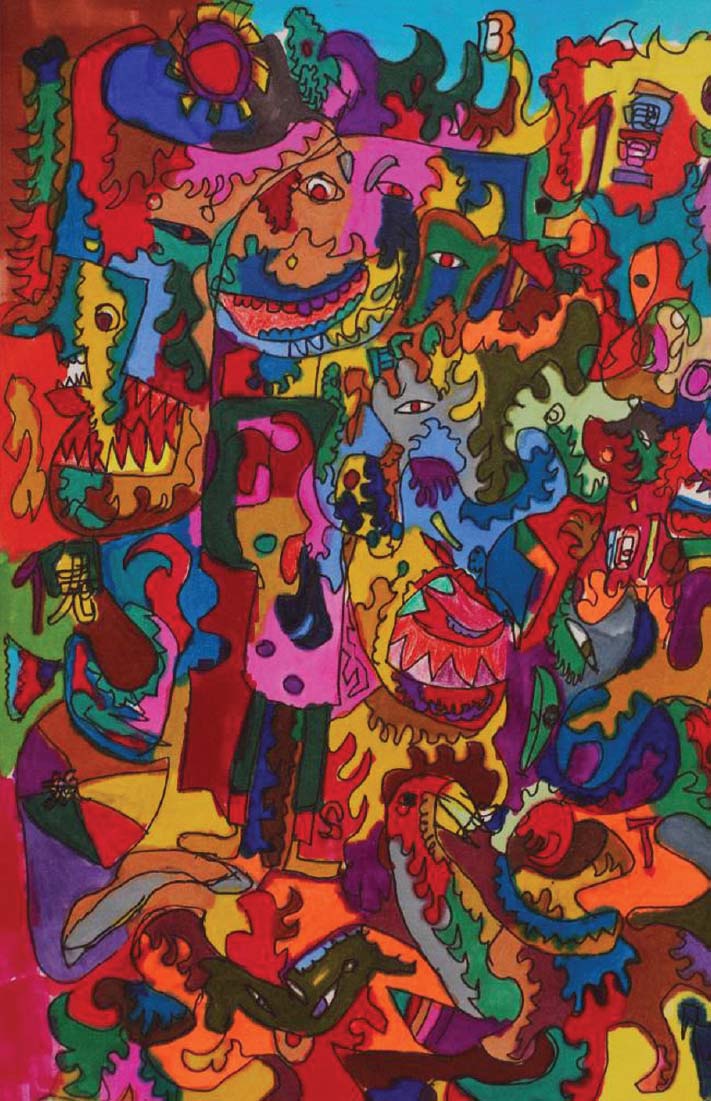

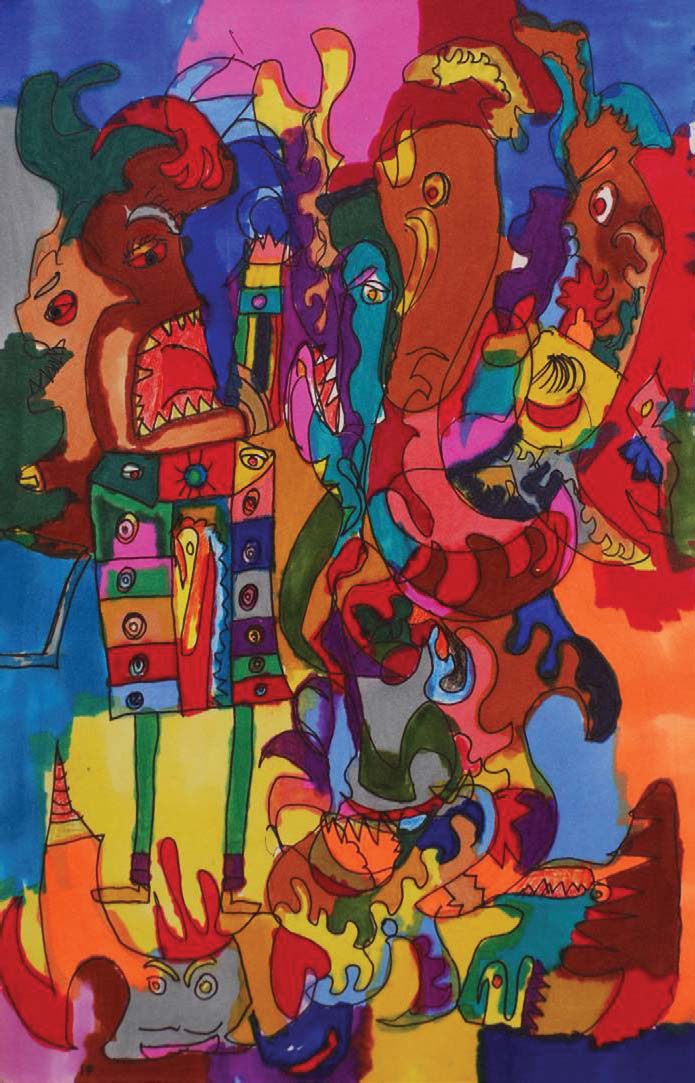

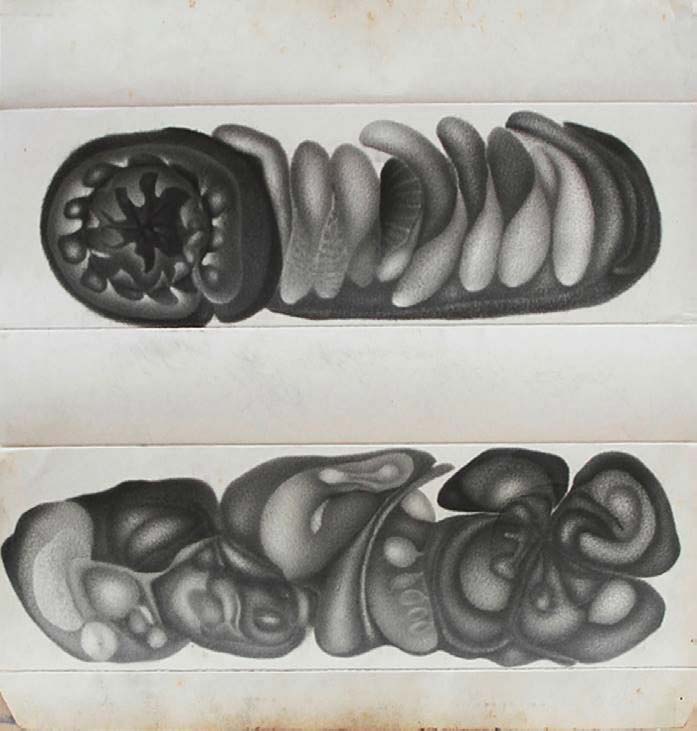

Guo Haiping: Yang Min (b. 1982, Nanjing) is living with severe chronic mental illness. His paintings remind us of totem patterns and take us into a spiritual world where everything has a soul – this is seen in his paintings Mythical Creature of Leaf and Mountains where nature and humans are integrated harmoniously. Most of Yang Min’s works were painted in his first two years in our studio; now that his mental state has become much more stable, his delusions and artistic inspirations have decreased. I believe that these artworks have helped to heal Yang Min and have, perhaps, fulfilled their role. Yang Min’s symptoms can be considered from a naturalistic perspective as active responses to life; they are protective mechanisms that set off the alarms that stimulate the saving of life. Here, there may be a gradual loss of the art but Yang Min’s condition has improved.

FIGURE 3 | Yang Min: Mythical Creature of Leaf, charcoal stick on paper, 53x38cm

FIGURE 4 | Yang Min: Mountain, charcoal stick on paper, 53x38cm

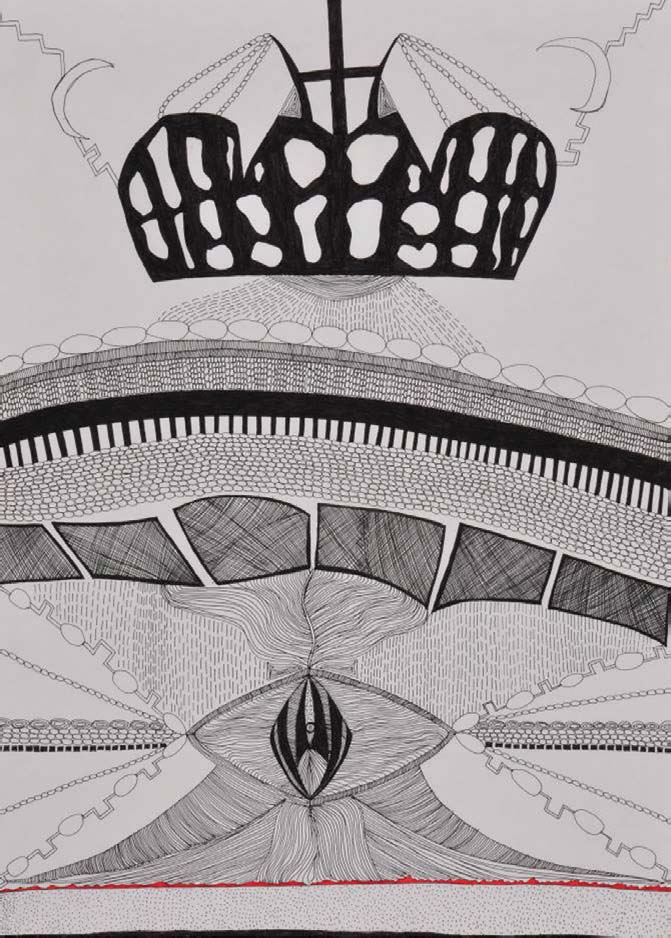

Li Jie (b. 1975, Nanjing) is another artist who is suffering from mental illness and constant delusions. Before coming to our studio, she controlled her thoughts mainly by medicines – not medications. After becoming involved with the studio, however, she began to paint her delusions. Painting makes Li Jie peaceful and she has clearly found a new way of controlling her disturbing thoughts. Her paintings also offer insights into the nature of her delusions and of how she perceives them.

Yi Fan (b. 1985, Nanjing) was born with a cognitive disturbance. Her paintings are her reflections of her feelings and experiences – not copies of objects. Her art offers people an opportunity to easily experience both her imagination and her means of expression.

Chen Baogui (b. 1987, Nanjing) suffers from epilepsy. This condition has effected heavy memory impairment that separates him from normal daily life, so Chen Baogui devotes himself to reading the Bible and communicating with God. After coming to our studio, he began to communicate with God through painting; now this art allows him to express his inner life more fully and more richly than simply by reading the Bible. It also enables him to have more contact with others in his daily life.

FIGURE 5 | Li Jie: Tower and Chains, gouache on paper, 53x38cm

FIGURE 6 | Li Jie: Stumps, gouache on paper, 53x38cm

FIGURE 7 | Yi Fan: Ninja Turtle, marker pen on paper, 53x38cm

FIGURE 8 | Yi Fan: Donald Duck, marker pen on paper, 53x38cm

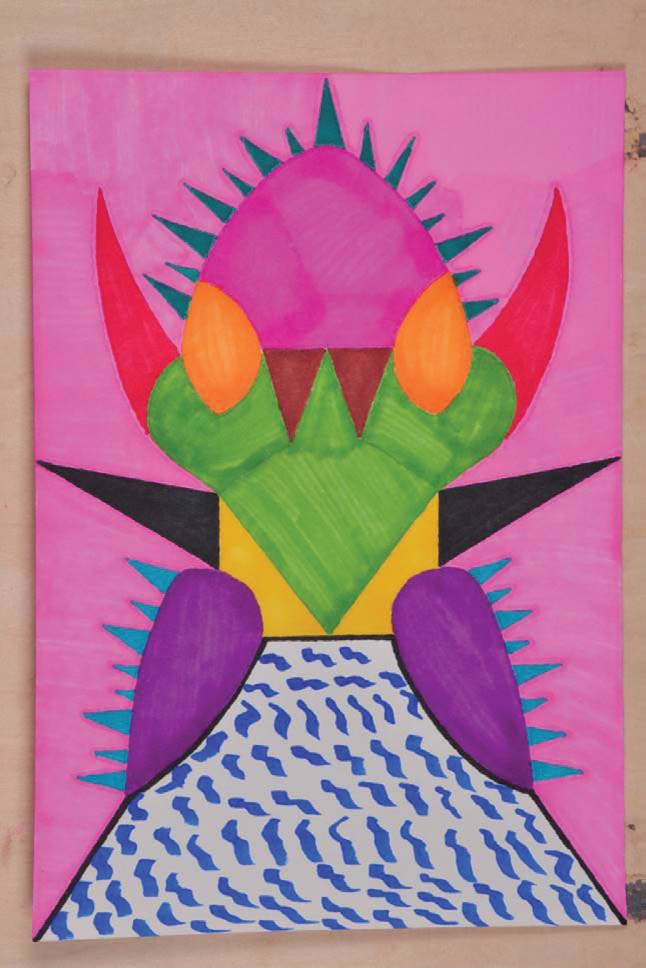

FIGURE 9 | Chen Baogui: Thorny Mask, marker pen on paper, 38x53cm

FIGURE 10 | Chen Baogui: Kite that Likes the Mask of Lord, marker pen on paper, 38x53cm

Qiao Yulong (b. 2000, Nanjing) suffered trauma at birth to the left side of his brain, so he relates to life and paints mainly with his right brain. His love of music is woven into his paintings.

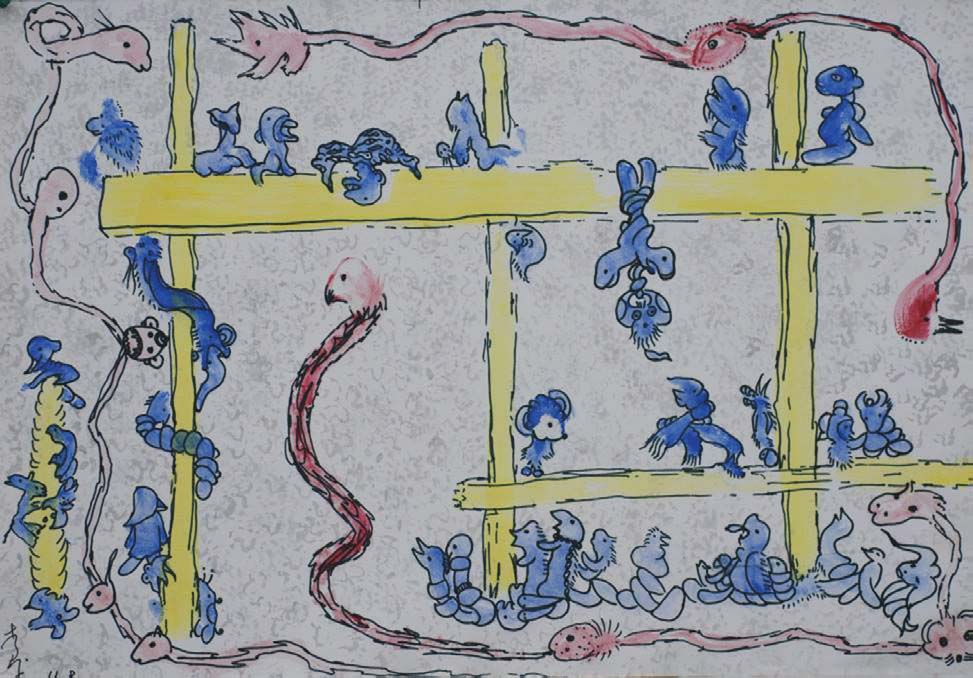

Other selected art works:

Chen Shushan: During the past decade, have your thoughts on outsider art changed in any way?

Guo Haiping: Great changes have taken place during the past decade. I began this project in order to solve my own puzzled and inconsistent thoughts about art and mental health; gradually the project turned into helping artists reintegrate into the community. Outsider art has also improved what I call our cultural ecology – the healthy interdependence of all people within society – a very difficult achievement from an holistic perspective. For me, retreating from these challenges is not an option – I and other Chinese people must continue to face them and address them while moving on boldly and courageously. Surprisingly, our work on outsider art in China has been furthered by expressions of international support and mutual understanding. Over the past decade we have undertaken best practice exchanges with colleagues in France, the Netherlands, Germany, the United Kingdom, Australia and Japan.

FIGURE 11 | Qiao Yulong: Work No.14, marker pen on paper, 13x19cm

FIGURE 12 | Qiao Yulong: Work No.17, marker pen on paper, 13x19cm

FIGURE 13 | Li Ben (b. 1963, male, Nanjing): Untitled, water color on paper, 54x38cm

FIGURE 14 | Li Ben: Untitled 2, water color on paper, 54x38cm

FIGURE 15 | Niu Niu (b. 1991, female, Beijing): Cosmic Union, colored pen on paper, 38x26cm

Chen Shushan: What has been your biggest challenge in the past decade? And your greatest success?

Guo Haiping: Our biggest challenge has been to effect a gradual change in cultural attitudes and in practices within spiritual, political and economic spheres. To solve such problems calls for a concerted effort from hundreds, thousands and even tens of thousands of people that will take several decades to achieve. From a personal point of view, my greatest success has been to find my own spiritual cradle from works of outsider art. I know where I come from and where I shall go – matters of profound significance to me.

FIGURE 16 | Niu Niu: Deer in Border Town, water pen on paper, 38x53cm

FIGURE 17 | Wu Meifei (b. 1968, male, Nanping Fujian): Bird, marker pen on paper, 45x55cm

FIGURE 18 | Wu Meifei: Untitled, pencil on paper, 25x27cm

Chen Shushan: What do you feel is the biggest problem faced by outsider artists in China today?

Guo Haiping: Today’s outsider artists are in need of the basic elements of existence and survival – namely uncontaminated soil, air and water – which can be referred to as humane ecology.

Chen Shushan: What is your vision for the future of this project?

Guo Haiping: We are now collating all original documents and information used to introduce the value of the outsider art works to the public. We are also focused on removing the ideological and institutional barriers to the implementation of additional programs and we hope to establish other economic support systems.

We share a common goal – namely to establish an outsider art community for artists based in China. This community will consist of three parts: a closed residence area undisturbed by the outside world, a semi-enclosed free creation area which could be opened to the public on a regular basis and an interaction area open to the public – an area which will include outsider art museums, research centers, galleries, cafes, hotels, markets and medical counseling centers, etc. This will be a community where artists can live, work and communicate with members of the public; the public will be able to enjoy and purchase the outsider art works as well as interacting face to face with the artists themselves. Economic benefits will be obtained by selling art works and their derivatives; this will greatly relieve some of the community’s financial pressures and will strengthen the survival of the artists in this community.

The reason why I aspire to establish this community is based on my conviction that we should not force these patients to fully adapt to the strictures of a conventional society. Temporarily, the biggest obstacles to their rehabilitation can be defined as both social and ecological; this group has limited adaptive capacity and ability for self-regulation. Moreover, I do not believe that a full adaptation to the external environment is neither an advantage nor a possibility for many people. Being unable to fit into today’s social surroundings cannot and should not be described as a disease. We can neither ignore these artists nor abandon them to their own fate. In my view, it is the social ecology – the inherent nature of productive social relationships – that should be changed. Establishing an outsider art community will provide a special zone where people can create together, can establish positive identities, can search for origins and achieve mutual understanding by working towards common goals – all through the channel of outsider art. In this way patients can contribute to a healthy cultural ecology – one where their creative role is appreciated as part of the whole.

Chen Shushan: You have been promoting the idea of mutual help in society; can you say something more about this?

Guo Haiping: We should offer each other mutual help in the face of life or death challenges. It is currently acknowledged that problems shared by a certain group cannot be addressed solely by their own efforts. We need others. This is what I mean by cultural ecology. In my practice, I find that many people who are deeply connected to our current society are both divided and disconnected from their own hearts and from nature. Ironically it is those who are labeled as emotionally “sick” who are sometimes more in touch with their own hearts and with nature – but they become victims and scapegoats when they do not relate fully to what we see as social progress. This dichotomy is not a problem to be solved by psychological and medical practices; it is a much larger, societal concern. We need to rely on each other for our well-being and for our common betterment.

Chen Shushan: How can outsider art further mutual help?

Guo Haiping: Outsider art helps us appreciate how all humans grow from the same deep sources and, indeed, may share common atavistic memories. Some of these memories may be sharp or out of focus (like a photograph) – but we have to identify the important elements that we share; the same underlying and sensitive film. Mental patients are prone to be conspicuous. Sometimes brutal reality forces their brains to shut down and they refuse to accept a great deal of social information. At the same time, we can see that they possess the capacity to inspire and to realize their potential; they deal with the harsh environment that challenges them by applying the innate wisdom and expressions inherited from their ancestors. It has been said that the thinking of many patients with mental illness is linked to the spirit of ancestral phenomena. These reflections and expressions are based on spontaneous survival mechanisms that cannot simply be defined as illness. Moreover, it is difficult for those who follow the tenets of mainstream society to create outsider art works for they are constantly absorbing the information that society requires them to accept and that information involuntarily covers the more intuitive areas of their minds. I believe they are temporarily restricted from accessing the genetic information and potential resources inherited from their ancestors. When the authentic perspectives presented by outsider artists catch their eyes, however, they are touched and drawn in by what they see. I acknowledge this as a moment of epiphany. Such an experience of enhanced perception creates a great opportunity – both here in China and globally – since everyone in this modern age is connected by mutually acknowledged influences. I believe the outsider artists could provide a valuable function within society; with their works being understood and cherished as valuable connections to an ancestral resource, they would lose much of their sense of isolation from mainstream society and their value within that society would rise. Outsider art could facilitate cohesive forces within the general community; it could further a sense of mutual understanding, respect and support – with everyone learning from one another and achieving self-perfection through mutual support and help.

About the author

Guo Haiping is the Founder & Art Director of Nanjing Outsider Art Studio. He was born in Nanjing in 1962 and is a contemporary artist and the pioneer of outsider art in China. Chen Shushan is the Research Manager of Nanjing Outsider Art Studio. He was born in Yulin, China in 1990 and received his B.A. in Sociology from Nanjing University in 2012.

References

Haiping, G. (2014). Notes on Outsider Art in China. Shanghai: Shanghai University Press.