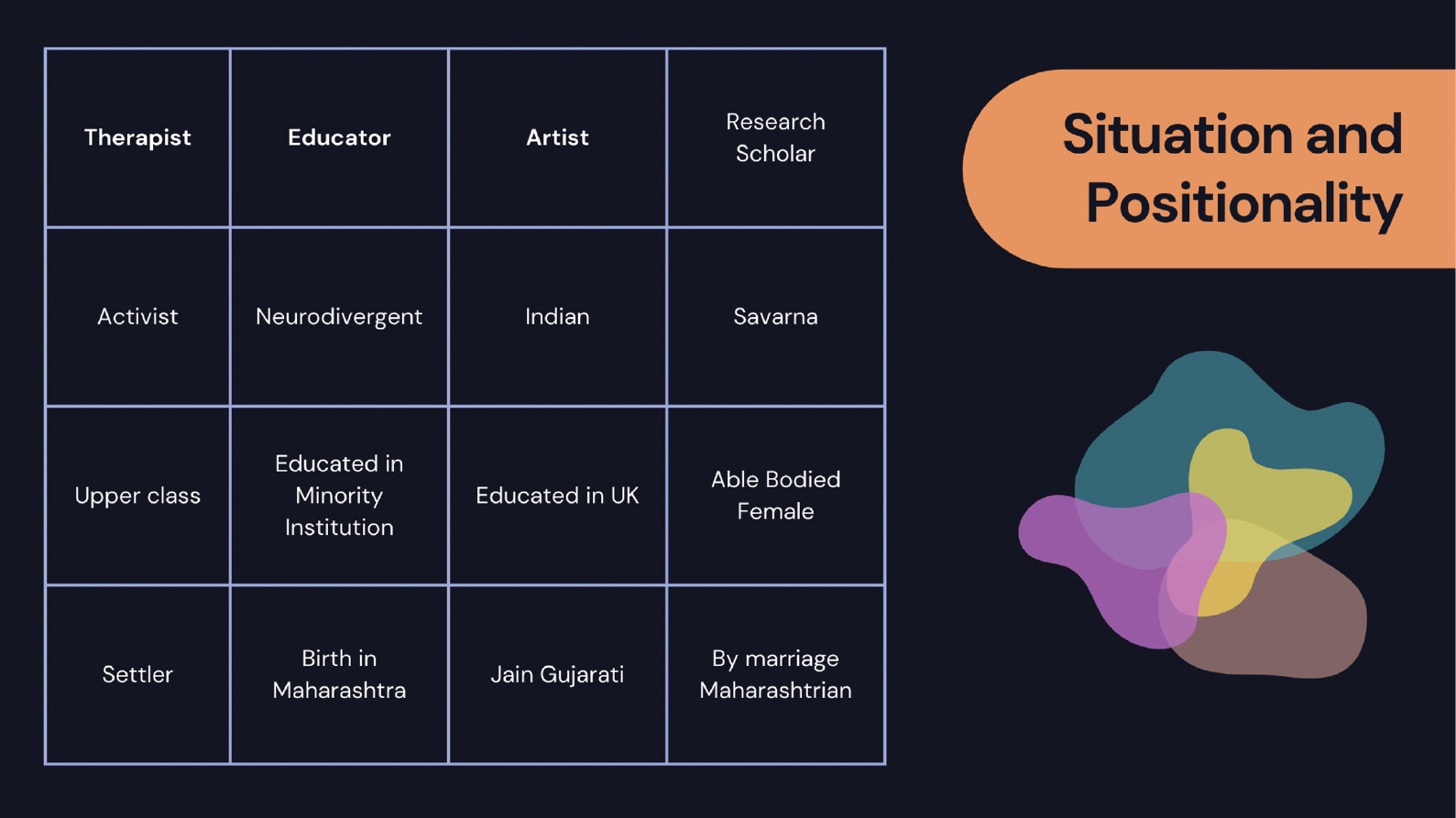

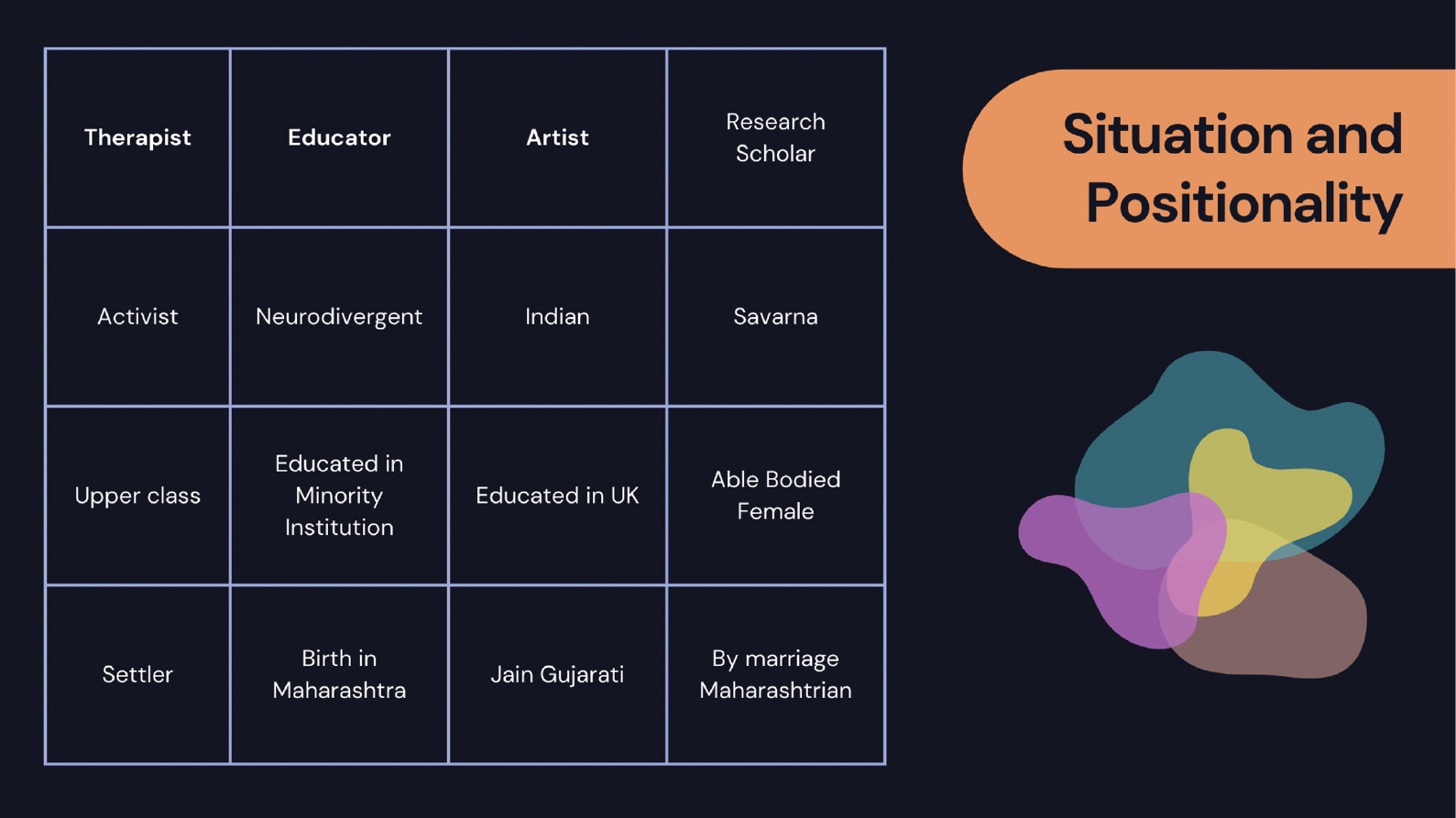

FIGURE 1 | Situation and positionality.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2024) 10(1):97–111 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2024/10/6 |

Embracing the Kahankar and the Ahankar: A Reflexive Inquiry into Body, Movement, and Consciousness, Interwoven with the Warli Philosophy

拥抱卡汉卡尔和阿汉卡尔:交织瓦利哲学与身体、动作和意识的反思性探索

Synchrony, India

University of Witwatersrand, South Africa

St. Xavier’s College (Empowered Autonomous Institution), India

Abstract

This article aims to deepen the understanding of existential intrasubjectivity and intersubjectivity as they relate to the body, being, and nature, as experienced through the lens of Warli philosophy, particularly the Kahankar and the Ahankar. This reflexive inquiry lies at the intersection of the author’s identity as a researcher, a dance movement therapist, and a spiritual being. The contemplation includes experiencing Nature as a witness, another facet of the Warli conviction of the profound interconnectedness with the natural world, recognizing our inherent composition as part of nature. Another dimension of engaging with this philosophy is through the practice of Authentic Movement, where the imagination, the psyche, and the soul all dance together as they are witnessed nonjudgmentally. I employed an external witness as well as used self-witnessing in the form of an “inner witness.” Lastly, it explores the dance between the body as the storyteller and the consciousness as the affirmer of the spoken word, the truth.

Keywords: Warli philosophy, Authentic Movement, consciousness, nature, cultural identity

摘要

本文旨在通过沃利哲学,特别是从《卡汉卡》和《阿汉卡》的视角,加深对身体、生存和自然界的存在主义中的主体内性和外性的理解。此反思性探究位于作者作为研究者、舞蹈动作治疗师和灵性生物的交叉点。在这沉思中,我以见证者的身份体验大自然。根据瓦利哲学,自然界是紧密联系在一起的,而我们是自然界固有的一部分。透过真实动作 (Authentic Movement) 我从另一个层面探究沃利哲学。在真实动作当中,想象力、心理和灵魂在不加批评的见证下共同起舞。我采用了外部见证者,并以"内在见证者"自我见证。最后,本文探讨身体(作为故事讲述者)与意识(作为言语和真相的证实者)之间的舞蹈。

关键词: 沃利哲学, 真实动作, 意识, 自然界, 文化特性

Introduction

The Warli Adivasis are referred to as Adivasis because the participants of the research identified as such and used this word to talk about themselves. This article does not go into the genesis of the term “Adivasi” and what it is to be one in India. As Xaxa and Devy (2021) state in their work, “Indigenous” was an anthropological tag that was assigned to local communities by European Colonialism, and there is ample evidence that these native dwellers have been talked about in folklore and stories, and many of their ways have been documented since prehistoric times in India. In the context of this article, the term Adivasi is used to represent the communities that share blood and cultural practices, are living in hilly and forested areas or can trace their ancestral ties to that land before being displaced, are sons and daughters of the land, and are the earliest people of the Earth (Shirsath, 2014). The word “Adivasi” translates to Adi meaning at the “beginning of times or original” and Vasi meaning “inhabitants” (Prasad, 2020). This term was coined in the 1930s to offer a sense of collective identity and to give them political power. They are a heterogeneous group of people spread across the Indian subcontinent with differences in their rituals and practices but finding commonality in their connection to Nature. To be indigenous in colonial and postcolonial India is to be severely institutionally marginalized in the economy, healthcare, education, politics, vocation, sociocultural benefits, land ownership, linguistics, and their way of life (Xaxa & Devy, 2021).

I would like to extend my gratitude to the elders, narrators, and artists of the Warli community for bringing me into the fold of their culture, ethos, and philosophies and for guiding me in my research work to decolonize and indigenize the work around identity exploration with preadolescent children. The philosophy this reflection is based on is drawn from the Warli community. I came across this philosophy while I was researching for my PhD. My research is a two-cycle action research program focused on arts-based identity exploration for preadolescent children of the Warli ethnicity. It employs different Warli art forms to explore various aspects of identity at this stage of development. The aim is to decolonize the process of identity exploration while using a community-engaged methodology to indigenize the process with cultural art forms of the same community.

Situation and Positionality

This paper is about looking through the lens of Adivasi philosophy at its core. It is important to delve into the intersections of my identity and how that impacts my reflexive process. In no specific order, I am a therapist, an educator, an artist, an activist, and a research scholar. I am an Indian, neurodivergent, able-bodied female. I have been educated in multiple institutions, some of them being minority institutions as well as in the UK. I am an upper class savarna. I also acknowledge that I am a settler even though I was born in Maharashtra. I am a Jain Gujarati by birth married to a Maharashtrian (Figure 1). As a researcher, I am not Warli Adivasi by ethnicity. I speak both Gujarati and Marathi languages, but the dialect is different from the one I speak.

FIGURE 1 | Situation and positionality.

As a committed outsider (Bozalek, 2011; Okin, 1995), I am aware of the privileges that my positionality rewards me with. Situated as a researcher external to the Warli cultural context, I employed embodied reflexivity to enhance my comprehension of their rituals and belief systems. Engaging with the Warli philosophies and artistic expressions through this approach did not entail an interrogation of the knowledge’s validity. Furthermore, by embodying these philosophies myself, I gained firsthand insights into their impact on the human experience. This process involves cultural appreciation, acknowledging the ancestral oppression, centering their art forms in their cultural identity, and actively witnessing and engaging with their ways of life. Restorative and reparative work at the grassroots level supports the decolonizing process and has an invariable impact on my own identity. While I initially approached the research project from the multifaceted perspective of educator, artist, therapist, and researcher, the research process itself foregrounded my positionality as a settler, a Jain Gujarati married to a Maharashtrian. This positionality significantly influenced the nature of my interactions with the participants.

Warli Adivasi Community

The Warlis are an aboriginal tribe that resides at the foothills of Sahyadris in Western India (Vadu, 2018). Due to urbanization, they have been pushed closer to the state boundaries of Maharashtra and Gujarat (Dandekar, 1998). Originally a hunting and gathering tribe, they have adopted an agropastoral lifestyle. They live closely connected to nature through rituals, their Gods, and their lifestyle. Warli art is one of the oldest art methods of showing the village community and documenting the music, dance, and life of the Warli tribe and is an insistent form of expression (Patil, 2017). As symbols are reproduced, it strengthens the sense of belonging and identity (Campanelli, 1996). It is in this experience that one can create meaning in the roles people play in the community, which are based on their own beliefs, customs, and traditions. Indigenous cultures emphasize the roles of imagination and storytelling in understanding selfhood (Atkins & Snyder, 2017).

Due to colonization, indigenous people are often perceived of as backward and primitive. While dismantling and critically evaluating North–Western knowledge systems and dominance, it is inferred that epistemic violence marginalized the indigenous people further (Bulhan, 1985; Dutta, 2018). It excludes the indigenous people as knowledge producers (Bulhan, 1985; Dutta, 2018; Lavallee & Poole, 2010). Their knowledge is considered illegitimate and uncivilized due to colonial oppression. Decolonization is the repositioning of the colonized as “thinkers, questioners, writers and researchers where there is an opportunity to emerge with new insights from the colonial wound assimilated with ancestral knowledge” (Dutta, 2018). Indigenous psychology is based on the knowledge generated by the indigenous communities and is not just offering a contrary viewpoint to Euro–American-centric psychological frameworks (Dudgeon et al., 2017). There is a key difference between the indigenization of knowledge and the decolonization of knowledge. The latter is based primarily on settler discourse while the former is based on indigenous knowledge production (Kovach, 2010). To learn about the many ways of understanding the life and beings of the Warli people, it is important to understand how this body of knowledge is further disseminated to subsequent generations.

The Warli Adivasis use art tableaus to convey the stories of their ancestors, life, philosophies, ethos, community rituals, oppression and justice, and their interconnectedness with Nature (Vadu, 2018). They also pass these stories down via oral pedagogy (Vadu, 2018). These take the forms of chantings by dhavlerins and suvasins (marriage priestesses), the dakya bhagats (Warli religious practitioners), in their rituals, by the thalavalas (community historians) (Prabhu et al., 2018; Vadu, 2018). The storytelling involves an active process of engagement on the part of both the storyteller and the listener, who then internalizes this wisdom through discussion and meaning-making. Depending on their intention, stories can be prescriptive, explore themes of feminism and antipatriarchy, delve into philosophy, recount history, or offer guidance to the oppressed. The neocolonizers and the current state-sponsored process equate their illiteracy to backwardness (Prabhu et al., 2018). Modern development often perpetuates the legacy of colonizers by marginalizing knowledge produced through oral traditions that developed from a close connection to nature (Dandekar, 1998). The traditions are subverted and disparaged. Decolonization emphasizes moving back from competitive antagonism to coevolutionary, collective, and collaborative systems. The focus is to center the wisdom of this community that is advanced humanistic and evidence of an eco-sentient society (Prabhu et al., 2018). Their physical, cultural, emotional, and spiritual existence is deeply interwoven with the forest, and this is visible in their epistemology, cosmology, and religious practices (Vadu, 2018).

The Kahankar and The Ahankar

I am because of you, just as you are because of me.

- Prabhu et al. (2018, p. X)

The Warli people utilize storytelling and visually arresting tableaus to transmit knowledge through a system of oral pedagogy. Most of this is not available in a published format due to various reasons like linguistic barriers, cultural preferences, epistemological violence during colonial and subsequent periods, dismissal and legitimacy of knowledge systems, gatekeeping and exclusion in academic spaces, and previous exploitation of this wisdom. Due to the paucity of written literature, this wisdom is drawn from the singular work of Prabhu, Prabhu, and the Kashtakari Sanghatna. They are the collectors, translators, and collators of this narrative that was narrated by the Warli Adivasis of District Thane, Maharashtra, India. The book is titled Wisdom from the Wilderness and was published in 2018. My conversations with the community elders and other members about this philosophy have added depth to my understanding of the story’s nuances and its true intended message.

The Kahankar (The Storyteller) and the Ahankar (The Affirmer) are in a relationship that ensures the passage of these narratives, the spoken word or the truth. The narratives have multiple layers and are deeply reflexive and engaging. This dance of being and becoming is from listening to being moved to moving and is a synergistic paradigm between the storyteller and the affirmer. The philosophical underpinnings of an affirmative society are at its core. The spoken word is potent and transformative energy. The “Ahankar” yearns to uncover and deepen the understanding of the cosmos. This is contingent upon a dialogical engagement with the storyteller. This relationship offers a sacred space to both, and the aim is to uncover the unspoken truths and nuances unseen. The affirmer validates both the story itself and recognizes the power of the narrator in their role as the carrier of knowledge and wisdom from the past. This energy transforms and transmits from the giver to the receiver and the community. This is the handing down of history and philosophy through stories within the symbiotic interconnectedness.

The Silent Keeper: The Tree as an Ahankar

Adivasis call themselves “Prakriti Pujaks,” which roughly translates to “Worshippers of Nature.” Their life is deeply interconnected with nature and their sustenance depends on the forests. Whilst living near nature, Adivasis have developed a biocentric ethical attitude of respect toward natural things like rivers, trees, animals, rocks, and mountains (Sen, 2007). Across different indigenous populations of the country, trees hold a deep cultural and spiritual significance (Ciocca & Dasgupta, 2015). The tree contains multitudes and is deeply sacred to the Warli Adivasis (Wolf et al., 2024). Trees are often the center of performance rituals and ancestral connections. Due to their ethnic value systems, they hold a deep reverence for trees and forests along with other creations of nature (Sen, 2007).

Upon visiting the site of my research, I was instantly drawn to this massive tree in the center of the school courtyard (Figure 2). Engagement with the Warli philosophy of ecocentrism fostered a deliberate deepening of my connection with a particular tree. This arboreal presence served as a grounding ritual, prompting pre- and post-session prayers expressing gratitude for its symbolic role in supporting my facilitation practice. The tree has been my Ahankar, a witness to the program unfolding and developing. The presence of the tree provided a container for both my inner turmoil and enthusiasm, fostering a sense of centeredness. The experience of safety engendered deep gratitude. The impact of the presence of the tree as the affirmer to my process is also seen in my post-session visual reflection using the Warli art form (Figure 3). This arts-based reflection also includes various natural elements, the wind, the sun, the rain, the dog, the paddy, and the tree. Since this was response art, it was not until the second cycle that I realized how I had integrated these elements into my facilitation experience. The more I immersed myself in integrating philosophy into my practice, the prayer evolved as a devotional ritual (Figure 4).

FIGURE 2 | Experiencing the presence of the tree, Cycle 1 (June 2023).

FIGURE 3 | Artistic reflection post-session in Cycle 1 (September 2023).

FIGURE 4 | Homage to tree ritual, Cycle 2 (January 2024).

The research spanned the multiple seasons that are observed in the Warli community’s agricultural practice, from June through the conclusion of data collection in February. This temporal aspect mirrored the cyclical nature of the action research process itself. The initial fieldwork period (June) served as the foundation, where the seeds of the research were planted. As the research progressed (akin to the flourishing of crops), data emerged from the first cycle, informing and enriching the second cycle (harvest). The tree also is a part of this natural cycle. My emotional and intellectual capacity was mirrored by the tree’s physical state. The process experienced a period of being abundantly resourced followed by a period of depletion and content emptiness as depicted in Figure 5. However, this depletion did not signify an end but rather a necessary precursor to further growth and the generation of new insights in the subsequent phase.

FIGURE 5 | Gratitude to the tree, last session Cycle 2 (February 2024).

Framed within the context of an emerging self-awareness, encompassing both communal belonging and connection to nature, the program facilitates the narrative construction of each participant’s being. This narrative as spoken through the emergent data is spoken truth. This process employs a multifaceted approach to truth-telling. Participants and their collective, referred to as “Kahankars,” engage in a collaborative exploration of identity. As the researcher, I initially assumed the role of the “Ahankar,” facilitating this process and compiling data. However, through ongoing engagement, I aspire to achieve a reciprocal knowledge exchange, ultimately becoming a Kahankar myself. This reciprocal nature is further emphasized by the symbolic presence of a tree as my “Ahankar.” Within the Warli worldview, trees are often perceived as repositories of knowledge, witnessing and holding narratives that connect to a broader cosmic understanding.

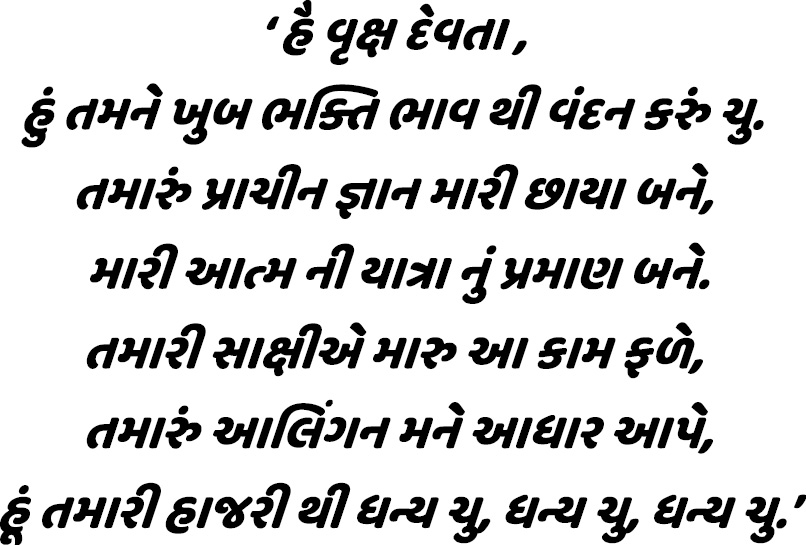

Prayer Ritual in Gujarati (My Mother Tongue)

Prayer Ritual Translation to English

Dear Tree God,

With great devotion, I bow my head to thee.

May thy ancient wisdom be my shadow,

Be the witness to my soul’s journey.

May this work of mine bear fruit in thy presence,

May thy embrace, hold me.

Blessed be thy presence, Blessed be thy presence, Blessed be thy presence.

Where Movement Meets Witness

A silent dance through shifting sands,

Digging deep, guided by the soul,

In my core a steady light,

In being witnessed, I become whole.

As a dance movement therapist, I am deeply interested in exploring the integration of body, mind, and spirit. My doctoral research utilizes action research methodology and integrates the researcher’s embodied reflections as a key component of data collection and analysis. In this context, the Authentic Movement is a powerful tool for self-discovery and self-reflexivity as a researcher. On deepening my understanding of the Kahankar and Ahankar philosophy in an embodied way, I felt a liberation in my movement. My imagination seemed to take flight while remaining rooted in my identity. Authentic Movement as a practice was pioneered by Mary Stark Whitehouse (Levy, 1988), which has also been called “Movement in Depth.” It’s an invitation to the mover to descend into their inner world with their eyes closed through movement. The mover is witnessed by their therapist/witness who creates a safe and contained space with their receptive embodied presence (Stromsted, 2009). Creative reflection helps anchor this experience along with sharing the experience by the mover and the witness. The witness responds to the mover’s corporeal, affective, and imaginative dimensions, integrating their sensations, emotions, and images. This response employs suspension of judgment, projection, and interpretation.

While navigating my doctoral research work, my reflexive work included Authentic Movement practice as a mover and in being witnessed by another person. When I view this through the lens of this specific philosophy, it emerges that my inner psyche narrates its story through movement, embodying the role of Kahankar. The witness, on the other hand, reflects the qualities of Ahankar. The energy exchange between the mover and the witness mirrors what is stated in the philosophy. The sacred process is a meditative experience for both the storyteller and the mover. There is an innate need in the body to express that which is unconscious. This active witnessing process allowed for my shadow self to emerge and created space in my body to process my experiences as a committed outsider to this research. I encountered the parts of myself that I had previously othered. These parts were laden with aspects of my privilege. My positionality of being a settler on the original Warli lands, being savarna (upper caste) and having access to resources that many of the participants in the research did not, played heavily in my body. This practice opened avenues for me to be an Ahankar to the embodied narratives the participants were bringing into the session. The interconnectedness of their beings with their land, their access to nature, and the simplicity of how they experienced the arts helped me to reclaim parts of me that I felt shame, guilt, and disappointment about. The work of Hillman (1991) requires love for the parts of ourselves that we consider perverse and unacceptable. The practice of witnessing the shadow self (Marlan, 2010) emerged especially in my sense of identity, which then put into perspective what aspects of myself were integrated into my persona and how I wanted it to shift in that. This work gained a deeper meaning as I looked toward indigenous philosophy and wisdom to tap into what is called the Golden Shadow. Working with the Golden Shadow (Plotkin, 2013), I am starting to move toward a more authentic and interconnected life by working with the inferiority that alienated my sense of connection with indigenous philosophies. This is also an active process of embodied decolonization and is my ethical responsibility as an embodied researcher.

I have experienced transformative shifts in this process. This practice has helped me widen my work within the unconscious by developing deeper into the cultural and archetypal layers, thus creating opportunities to tap into the collective unconscious (Stromsted, 2009). Insights from this practice during the research process illuminated the reasons and my motivations to actively distance and disengage from specific community practices. They have contributed to my evolving sense of self and cultural identity. Integrating them and actively engaging with them led to me taking accountability for my positionality and embracing my community practices without prejudice. This has woven itself into the fabric of how I approach and facilitate my sessions. It has changed how I express my intention of bringing indigenous art forms to explore identity. It has also impacted how I translate this understanding and revelation for intergenerational healing and create space for exploration for my child in my personal life and the gratitude I have for these forms. In this process of moving I was being moved, and in this process I was gaining agency (Cahill, 2015). This resonates with the philosophy that this energy creates agency and change, which are then integrated into Ahankar’s existence and way of being in the community.

Through many years of Authentic Movement practice, I have learnt to develop an “inner witness” that allows me to integrate my experiences and feel revitalized in this process. I draw upon the form of Authentic Movement in my research process and apply what I have learned as a witness in this form to apply moving and self-witnessing as part of my research methodology. Through the cultivation of expansive modes of being, moving in this way facilitates a state of empowered dance of surrender guided by a choice to actively self-witness this dance (Hartley, 2015). The inner self witness in its heightened self-reflexive state is about “watching as we do” and not being merged with the material that moves in this process (Bacon, 2015). My inner witness, which embodies the qualities of Ahankar, discerns the meanings that emerge through this practice. It affirms the truth as experienced by my body and acts as a portal to understanding the workings of my unconscious. This field of practice has helped me develop the capacity to articulate embodied experiences as a facilitator of the expressive art program integrated with my role as a researcher. According to this philosophy, the Kahankar represents my unconscious. My body and movements become the vehicle through which it expresses its truth. The inner witness, along with the external witness, embodies the qualities of Ahankar, which is responsible for integrating this articulation of truth.

The Song of Becoming: The Body and the Being in Dialogue

Whispers of wisdom, the Spirit alive,

Tapping into the cosmos, waiting for the essence to arrive.

Ancestral echoes, ethereal by design,

The body and the being, in a dance divine.

My spiritual practice centers on cultivating a deeper connection with my body. Initially, I embraced the philosophy that this connection was the key to unlocking my spirit’s voice. However, as I immersed myself more fully and integrated the wisdom of Kahankar and Ahankar philosophy, I came to recognize it as merely the first step on a broader journey.

Previously, I viewed my spirit as the “Ahankar” within the narrative my body sought to express. However, with heightened attunement to my spirit’s voice, I observed a reciprocal dynamic: my body intently listened and actively responded to ancestral and collective knowledge. In Hinduism, this knowledge is referred to as the Akashic records, a metaphorical archive of all thoughts, words, deeds, and events in the universe, believed to express profound truths across time and space.

Through movement and meditation, I facilitated the seeking of truths from my being. These truths varied in their clarity: some were more challenging to decipher, others manifested symbolically, and yet others held a tangible immediacy.

The divine feminine energy has been a force to harmonize my inner turmoil. The need to connect with this energy emerged as a revelation during the soul-searching process. This revelation intertwined with another truth demanding confrontation: a deep-seated shame profoundly influenced by colonialism and past experiences of dancing during Navratri. Examining my cultural identity through a self-reflective lens, as a researcher would, revealed how these factors combined to create a significant dissonance in my engagement with the festival. Navratri is a nine-day Hindu festival that celebrates the divine feminine in honor of the Hindu Goddess, Durga. The tenth day, Dussehra, is about the triumph of Durga over the demon Mahishasura symbolizing the Victory of good over evil. This can be interpreted as a metaphor for overcoming internal negativity or aspects of oneself that are counterproductive.

Garba is a folk dance form that finds its roots in the Gujarati ancestry. It is performed in the community gathering that spans all nine nights of the Navratri festival. Notably, participation transcends gender stereotypes and welcomes people from all faiths and backgrounds. The term “garba” itself originates from the Sanskrit word “garbha,” meaning “womb.” This reinforces the symbolic link between the dance and the life-giving power of the feminine divine. The cyclical nature of time is represented by the circular formations during the dance, which involves various rhythmic synchronized movements maintained by claps.

It is compelling to note that this reclamation of my power coincides with the birth of my child and engagement with this philosophy. The festival has been very dear to me since childhood and is integral to my cultural heritage. During my first year of postpartum, my disconnection from this festival was amplified. As I delved deeper into this philosophy and examined my cultural identity through a self-reflective lens, I began to practice deep listening to my body’s needs.

My relationship with my womb and the pelvic region has undergone a dynamic transformation since pregnancy. In the second year of post-delivery, I committed to immersing myself in the divine feminine energy and the festival’s power for all nine nights, even when I grappled with resistance from my mind and body.

This commitment culminated in a potent release of creative power. I embraced the potential for a powerful connection, passing this dance tradition to my daughter as an intergenerational resource. Championing the expression of my authentic truth free from the influence of past experiences, I danced with my community for three to four hours each night on all nine days. This transformative experience defies articulation. The ensuing spiritual intimacy, arising from this embodied dialogue, left profound imprints on my being. My body became a vessel for sharing previously unacknowledged narratives, some deeply challenging to confront. The collective wisdom I accessed through this process facilitated the transcendence of ingrained shame. At a cellular level, I felt a life-altering sense of aliveness. My body became a gateway, fostering a sense of openness to the cosmos and the collective energy it embodies.

This transformation was contingent upon a unique dialogue between my body and spirit, guiding me toward my most authentic spiritual self. When necessary, the body served as the “Kahankar” and the spirit became the “Ahankar.” Conversely, when receptivity to universal knowledge was paramount, my body assumed the role of the “Ahankar.”

Conclusion

This PhD process has served as an agent for personal transformation. Rediscovering and reconnecting with my cultural identity has been an alluring part of this process that involves designing a program centering on indigenous arts. This exploration has unearthed previously suppressed aspects of myself, leading to a profound sense of belonging and self-understanding. This has reignited my spiritual path that I embarked upon a decade prior. The ingenious wisdom of the Warli people transcends colonial frameworks of superiority. Their profound connection to the land and nature is strikingly evident in the knowledge they transmit across generations. Their oral narratives are an artistic expression of ancestral systems, their oppression a guide on weaving their ethos into their daily life. Internalized colonialism and my social location had distanced me from many such practices and resources. Throughout this unfolding process, I have had the distinct privilege of serving as an “Ahankar,” a medium for receiving and processing emerging truths. This immersive experience has fostered a deeper appreciation for the transformative potential of indigenous art forms and their capacity to bridge the gap between personal identity and cultural heritage. My deepest gratitude to the wisdom and generosity of the Warli people from Palghar District, Maharashtra, who have shared their way of life with me.

About the Author

Devika Mehta Kadam is a registered Dance Movement Psychotherapist (R-DMP). She is the Program Head for the Post Graduate Diploma in Expressive Arts Therapy at St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai, and faculty for Diploma courses in Dance Movement Therapy. She is the Co-Founder of “Synchrony” and the Founding Board Member of the IADMT. She is the Regional Director of Asia for the International Association of Creative Arts in Education and Training. She is currently a PhD candidate at The University of Witwatersrand, South Africa. She holds a masters in Dance Movement Therapy, Applied Psychology (Clinical) and Indian Folk Dance.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: devikamehta.synchrony@gmail.com; ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0009-0009-1424-0033

References

Atkins, S., & Snyder, M. (2017). Nature-based expressive arts therapy: Integrating the expressive arts and ecotherapy. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Bacon, J. (2015). Authentic movement: A field of practices. Journal for Dance and Somatic Practices, 7(2), 205–216.

Bozalek, V. (2011). Acknowledging privilege through encounters with difference: Participatory learning and action techniques for decolonising methodologies in Southern contexts. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 14(6), 469–484.

Bulhan, H. A. (1985). Black Americans and psychopathology: An overview of research and theory. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 22(2S), 370–378.

Cahill, S. (2015). Tapestry of a clinician: Blending authentic movement and the internal family systems model. Journal of Dance & Somatic Practices, 7(2), 247–256.

Campanelli, M. (1996). Pioneering in Perth: Art therapy in Western Australia. Art Therapy, 13(2), 131–135.

Ciocca, R., & Dasgupta, S. (2015). Introduction. Out of hidden India: Adivasi histories, stories, visual arts and performances. Anglistica Aion: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 19(1), 1–11.

Dandekar, A. (Ed.). (1998). Mythos and logos of the Warlis: A tribal worldview (Vol. 4). Concept Publishing.

Dudgeon, P., Bray, A., D’costa, B., & Walker, R. (2017). Decolonising psychology: Validating social and emotional wellbeing. Australian Psychologist, 52(4), 316–325.

Dutta, U. (2018). Decolonizing “community” in community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 62(3–4), 272–282.

Hartley, L. (2015). Choice, surrender and transitions in Authentic Movement: Reflections on personal and teaching practice. Journal of Dance & Somatic Practices, 7(2), 299–312.

Hillman, J. (1991). The cure of the shadow. In Meeting the shadow: The hidden power of the dark side of human nature (pp. 242–243). GP Putnam’s Sons.

Kovach, M. (2010). Conversational method in Indigenous research. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 5(1), 40–48.

Lavallee, L. F., & Poole, J. M. (2010). Beyond recovery: Colonization, health and healing for Indigenous people in Canada. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 8, 271–281.

Levy, F. J. (1988). Dance/movement therapy. A healing art. AAHPERD Publications.

Marlan, S. (2010). Facing the shadow. In Jungian psychoanalysis: Working in the spirit of CG Jung (pp. 5–13). Open Court Publishing.

Okin, S. M. (1995). Inequalities between the sexes in different cultural contexts. In Women, culture, and development: A study of human capabilities (pp. 274–297). Clarendon Press.

Patil, D. K. (2017). Warli art: Diversification of traditional painting. Creating future, hope & happiness. International Journal of Home Science, 3(3), 451–456.

Plotkin, B. (2013). Wild mind: A field guide to the human psyche. New World Library.

Prabhu, P., Prabhu, S. B., & Sanghatna K. (2018). Wisdom from the wilderness: Painted and narrated by the Warli Adivasis of District Thane. Earthcare Books.

Prasad, A. (2020). Ritual and cultural practice among Indian Adivasis. In Environment and belief systems (pp. 10–30). Routledge India.

Sen, P. (2007). Philosophising Adivasi ecological perspective. In Forest, Government and Tribe (pp. 48–59). Concept Publishing.

Shirsath, S. (2014). Adivasi tribe: Nature and concept. Online International Interdisciplinary Research Journal, 4(2), 401–406.

Stromsted, T. (2009). Authentic Movement: A dance with the divine. Body, Movement and Dance in Psychotherapy, 4(3), 201–213.

Vadu, M. (2018). The mystical world of Warlis. Notion Press.

Wolf, G., Vayeda, T., & Vayeda, M. (2024). Seed. Tara Books.

Xaxa, A., & Devy, G. N. (2021). Being Adivasi: Existence, entitlements, exclusion. Penguin Random House.