Cultural Appropriateness, Arts-based Care and Well-Being in Sensitive Research

敏感研究中的文化适宜性、基于艺术的照料和健康

Ying (Ingrid) Wang

The University of Auckland, New Zealand

Abstract

This article explores the nexus of cultural appropriateness, arts-based care, and well-being in sensitive research on sexual violence, with a focus on New Zealand’s Asian community. Drawing on the author’s background as an Asian immigrant arts-based researcher, this study underscores the pivotal role of care, both culturally and through arts-based approaches, in facilitating understanding and expression. Emphasizing the importance of caring for both research participants and the researcher’s own well-being, the article advocates for culturally sensitive practices throughout the research process. It demonstrates how arts-based research methods enable creative expression and deeper cultural comprehension, enhancing care provision for participants. Moreover, the article highlights the need for culturally sensitive self-care strategies for researchers, acknowledging the emotional toll of engaging with sensitive topics. Ultimately, it calls for a more compassionate, culturally attuned, and ethically grounded approach to sensitive research within diverse cultural contexts.

Keywords: cultural appropriateness, arts-based care, Asian, youth, sexual violence survivor

摘要

本文以新西兰的亚裔社区为重点,探讨敏感(性暴力)研究中的文化适宜性、基于艺术的照料和健康的交会点。本研究利用作者的亚裔移民及艺术研究者的背景强调关怀—无论是在文化上还是艺术本位的方法—在促进理解和表达方面的关键作用。论文强调关心研究者和来访者的自身健康的重要性,并提倡在整个研究过程中采取文化上适宜的做法。艺术本位的研究方法能促进创造性表达和更深入的文化理解,从而加强对来访者的关怀和保护。此外,本文强调研究者需要采取文化上敏感的自我照料的策略,认识敏感话题的研究会造成在情感上的伤害。最终,文章呼吁采取更具仁爱、文化适宜性和基于伦理道德的方法来在不同的文化背景下进行敏感课题的研究。

关键词: 文化适宜性, 基于艺术的照料, 亚裔, 青年, 性暴力幸存者

A Conversation with a Potential Participant

It has been challenging in the several months since my research project commenced. As an immigrant arts therapist who has worked extensively in the therapy field, specializing in assisting immigrant clients and sexual violence survivors, I anticipated that this research project journey would be difficult. However, I did not anticipate the profound emotional impact it would have on me.

This research project centers on the support of young Asian sexual violence survivors within the New Zealand school system. As an arts-based qualitative research endeavor, the research design involves recruiting three types of research participants from the community: young Asian survivors, their caregivers, and their educators/teachers/school counselors. Being a part of the Asian immigrant community myself, with my cultural knowledge, practice experience and life experience, I understand that sexual violence is a taboo topic in many Asian sub-cultures, including among Asian immigrants living in Western countries such as New Zealand (Fontes & Plummer, 2010; Foynes et al., 2014; Roberts et al., 2016; Robertson et al., 2016). I recognize the need to be careful in approaching potential participants. Three months into the recruitment phase, I find myself exhausted from engaging with NGOs, reaching out to my therapist friends and academic colleagues, and approaching teachers and school counselors. Unfortunately, the outcomes of my efforts have been disappointing.

During my third attempt to speak to a potential participant, who is a caregiver of a young Asian sexual violence survivor, she was initially hesitant to communicate through email exchange. Still, she agreed to talk to me over the phone upon learning that I could speak her first language, Chinese. During our phone conversation, I carefully explained my research, emphasized the confidentiality of participation, and addressed any questions she had about the participation information sheet. When she asked, “What are my benefits for participating?” and I mentioned the research goal of improving support for young Asian sexual violence survivors and their families, she responded with an emotionless voice.

In a world of differences, we stood apart,

She, a mother with an aching heart,

And I, a researcher with dreams to chase,

Yet our worlds collided in the same space.

She said, “You are Dr academic, and I am nothing,

We are too different, worlds apart, I’m finding.”

Uncomfortable, she spoke, with a heavy sigh,

As when she saw her daughter’s mini skirt so high.

“To be honest,” she continued, her voice emotionless,

“I just want to be selfish; I can’t disguise,

My daughter’s moved on from that painful event,

Why should I talk about it, let others benefit?”

The conversation became disengaged, and I found myself unsure of how to respond. I suspected that the research aims and goals outlined in my research design might hold little meaning for her. Respecting her feelings, I politely thanked her for taking the time to talk to me. After ending the call, a strong discomfort settled in my body. Despite being uncertain about the cause, I felt a pressing need to talk to someone. Leaving my office, I reached out to a therapist friend for peer support. This therapist friend, also a Chinese immigrant, provided valuable insights. When I described the discomfort in my body, she remarked, “I guess you are feeling a kind of pain.” Confused, I asked, “What kind of pain?” She responded with a Chinese saying: “愛之深,痛之切! [deep love, therefore, deep pain]. You are in pain because you care!”

Care and Ethics of Care

Before my academic career, I worked as a clinical arts therapist in the healthcare system. I understand the important role of care in my clinical practice, as the term “healthcare” itself attests to this reality, signifying the overarching purpose of the healthcare system and the individual endeavors within it—to deliver care (Krause & Boldt, 2017, p. 1). The existing literature underscores the central role of care primarily concerning personal, dyadic relations, as well as in the broader contexts of justice and political theory (Groenhout, 2004; Held, 2006; Pettersen, 2008; Pulcini, 2013). Krause and Boldt (2017) define the concept of care in healthcare as “a set of relational actions that take place in an institutional context and aim to maintain, improve or restore well-being” (2017, p. 3). This definition highlights three key aspects of care that hold particular relevance within the healthcare system: relationality, institutionality, and well-being (Krause & Boldt, 2017). Nevertheless, this definition does not focus on the concept of care in research, in particular, health research in the community.

Pettersen (2008) delineates the contrast between “thick and thin care,” where “thick care” is directed toward individuals with established relationships, such as family and friends, while “thin care” is provided when there is no established connection between the caregiver and the cared-for. As an immigrant, therapist and researcher, my research project involves both “thick and thin care.” In my trauma-informed arts therapy work, I often have the privilege of hearing hidden stories from clients who do not have a pre-established connection with me. However, when I received referrals for young sexual violence survivors, some of them were from the same schools my children attended/attend. Despite declining the referrals to avoid conflicts of interest, these cases raised concerns about my own children within the same community. Although developing the research proposal for this sensitive topic, I grappled with both aspects of “thick and thin care.” Regardless of these distinctions, I connect with the community under study through my professional practice, daily life, and cultural background.

Care ethics focuses on determining appropriate actions or reactions by relying on real-life situations rather than abstract rules; it emphasizes developing fitting responses based on the unique aspects of each situation, recognizing that applying rules alone may not adequately address specific circumstances (Maio, 2017). In ethics of care, a portrayal of human lives is highlighted, emphasizing interdependency, embodiment, and social connectedness (Groenhout, 2004). The ethics of care primarily centers on the responsibility toward generalized others, and mature care involves the capacity to navigate between diverse groups of potential recipients as well as balancing the interests of oneself and others (Pettersen, 2008, p. xv). As a researcher who is also an immigrant within my own ethnic community, I must formulate suitable responses grounded in real-life situations and social connections. Additionally, these responses are shaped by my intrinsic desire to care for my community on a personal and embodied level.

In this article, I explore the concepts of care and care ethics within the framework of sensitive research on sexual violence within the Asian community. I investigate the interplay among cultural appropriateness, arts-based care, and the significance of well-being in the context of this sensitive research. Utilizing critical autoethnography and arts-based methods, this study emphasizes the vital role of caring for research participants within the Asian community. Additionally, it underscores the importance of prioritizing the self-care of the researcher when undertaking sensitive research.

Care for Different Roles in Sensitive Research

Engaging with sensitive subjects within a culturally diverse community can exact an emotional and psychological toll. In this sexual violence research involving the New Zealand Asian community, I have multifaceted roles that bring multifaceted emotions into my embodied experience throughout the research journey.

As a therapist, I feel powerless,

Burdened by the world, as I often confess,

I cannot help everyone who needs aid,

Some don’t even know where to have their voices heard.

As a Chinese immigrant, I understand her plight,

The struggles she faces, both day and night,

And as someone also from a distant land,

My heart aches the same, to feel her resentment.

As a researcher on this taboo topic, my power felt weak,

Unable to assist, the future seemed grim and bleak,

Some people’s pain remained hidden or too late to uncover,

Leaving me, like that mother, feeling suffocated.

Securing research funding for this sensitive topic was a demonstration of care for my therapist role. Many years ago, a colleague suggested that I become an ACC (Accident Compensation Corporation) ISSC (Integrated Service for Sensitive Claims) therapist, providing therapy to clients who have experienced sexual violence. Without extensive research but driven by a caring commitment to sexual violence survivors, I became one of the first ISSC providers with an ethnic background in New Zealand. During my time practicing trauma-informed therapy for ACC ISSC clients, I was the sole Chinese-speaking ACC ISSC therapist listed on their “Find Support” website. Owing to the scarcity of Asian therapists assisting sexual violence survivors, I frequently received referrals for Asian survivors, resulting in an extensive waiting list for those Asian survivors seeking therapy support for their well-being.

In my capacity as a therapist, I discovered the position of a privileged observer (Wolcott, 1988). I have heard numerous hidden stories within our Asian community. Many clients lacked support in their adopted country, New Zealand. They often had no family in the country, limited language proficiency, and carried a heavy burden of shame due to stigmas around mental health and sexual violence within the Asian community. The existing systems, including the health system, justice system, and school system, were often not culturally sensitive to the needs of these Asian survivors. The frustration of feeling powerless to assist everyone in need within the Asian community lingered in my heart for many years. When the opportunity arose to develop a research project in my academic role, the emotions stemming from years of frustration became a driving force. When I decided to step away from my therapy work to focus on my full-time research position, I needed to refer out all my clients. I remember in one of these final sessions with my sexual violence survivor clients, I said to a young Asian survivor: “I leave my therapy work for now, but I am not leaving my passion for our community behind. I am seeking the opportunity to empower me to make a meaningful impact on my people and my community through my research.”

Being a Chinese immigrant, I understand the burden in Asian cultures, especially in terms of the topic of sexual violence. My identity formation as an immigrant therapist/researcher is influenced by my own displacement experience and moving between my root culture and my adopted culture (Wang, 2023). My immigration experience put me in a unique position in the research—“a native”; that is, I am both a researcher and a participant in this research on the Asian community (Allan, 2017, p. 43). As a Chinese immigrant, my presence might impact how my research participants engage with me. However, determining the suitable and acceptable extent and manner of involvement and participation in research requires a great deal of care (Kleinman & Copp, 1993, p. 48).

During the interview phase of this research, while conversing with young Asian sexual violence survivors, I observed my need to pause and take deep breaths as I listened to their narratives. At that moment, I openly communicated my emotions to the participants, recognizing myself not only as a researcher but also as an immigrant and a fellow human being engaged in this research. I took advantage of this opportunity to encourage my participants to prioritize self-care during the interview process, emphasizing the importance of gentleness in caring for both the researcher and the participants. I have observed that my attention to my own emotions, my empathy for participants based on my own experiences of displacement, and my conscientious approach to the research process built trust with participants in this sensitive research. They perceive the genuine passion of an immigrant from our Asian community behind my professional title.

In my role as a researcher, my responsibilities to research participants differ from my role as a therapist to my clients. Although I utilize my professional knowledge to create a safe and comfortable interview space, unlike in therapy, I cannot offer ongoing support to participants. Many of these research participants currently lack support from the health or school systems, yet based on my clinical experience, I recognize the potential benefits of engaging in therapy to address their traumatic experiences. I also recognize the power of arts in providing care to these research participants, allowing them to experience the healing power of creativity during the interviewing process.

Care with Creativity

In acknowledging the limitations of my role in providing assistance as a researcher, I embrace my identity as an arts-based researcher. Creativity becomes a distinct form of care for both the researcher and the participants in this sensitive study—a form of care approached from both a cultural perspective and an arts-based research standpoint. This holistic approach to care not only enriches the support offered to research participants but also underscores its importance in fostering the mental and emotional well-being of the researcher.

On this research road, I faced despair,

Emotions ran deep, and it felt unfair,

But in our shared moments of powerlessness,

We hope to find strength, spirit, and tenderness.

So let us strive in the arts-based journey ahead,

To bridge the gaps so painful voices can be heard,

In the kingdom of academia, though we may fall,

Together, we rise, breaking down the cruel stone wall.

The care ethics inherent in creative endeavors can only be fully understood and valued through the application of inventive methodologies, allowing researchers to delve into the relational aspects of creative work (Langevang et al., 2022). Human creativity encompasses a structured practice of care wherein individuals mutually nurture their ideas and expressions (Wilson, 2018). In the context of this sensitive research, the creation of art during interviews is conceived as unfolding in “a series of relational acts” (Thompson, 2020, p. 43). As a researcher, witnessing the art-making process and engaging in conversations with research participants about their work has been immensely gratifying for me in terms of comprehending the impact of relationships and care on their artworks (Langevang et al., 2022). Arts-based research serves as a platform through which the emotional, aesthetic, and relational dimensions of experiences are frequently conveyed and captured more effectively than through language alone (Ward & Shortt, 2020). Through creativity, I deliver my care to the research subject, the research participants, and the relational aspects of their creative artwork. I see this process as arts-based care.

In this sensitive research, I engage in arts-based care for both the research participants and me as the researcher. I use an arts-based interviewing process to extend the necessary care in addressing the sensitive topic of sexual violence. Art-mediated interviewing has proven to be a valuable method for gathering, analyzing, and representing qualitative study findings in the interaction between the researcher and participants (Deakin-Crick et al., 2012; Wang, 2013, 2016). By utilizing arts-based care, the interview questions do not explicitly address traumatic events. Instead, they use metaphorical or symbolic language, encouraging participants to delve into their complex emotions through tangible elements such as colors, lines, shapes, objects, and poetic expressions. In this article, my intention is unfold not to the whole narrative from the interview process but the moments the arts-based care occurred through creativity.

Using arts-based care, as a researcher, I inquire: “What kind of metaphor symbol would you draw, or write or any kind of way you want to express yourself to visualize yourself regarding the time when you needed the support?”

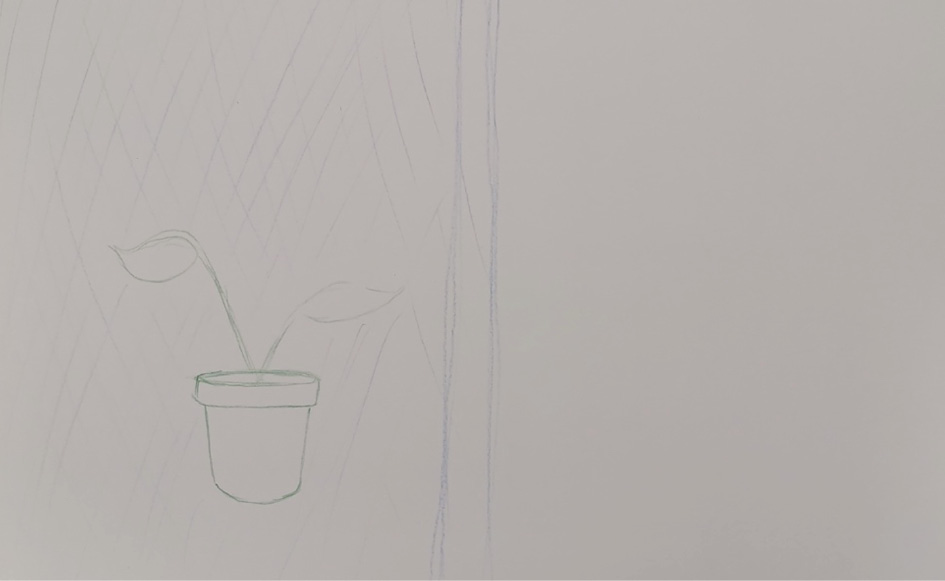

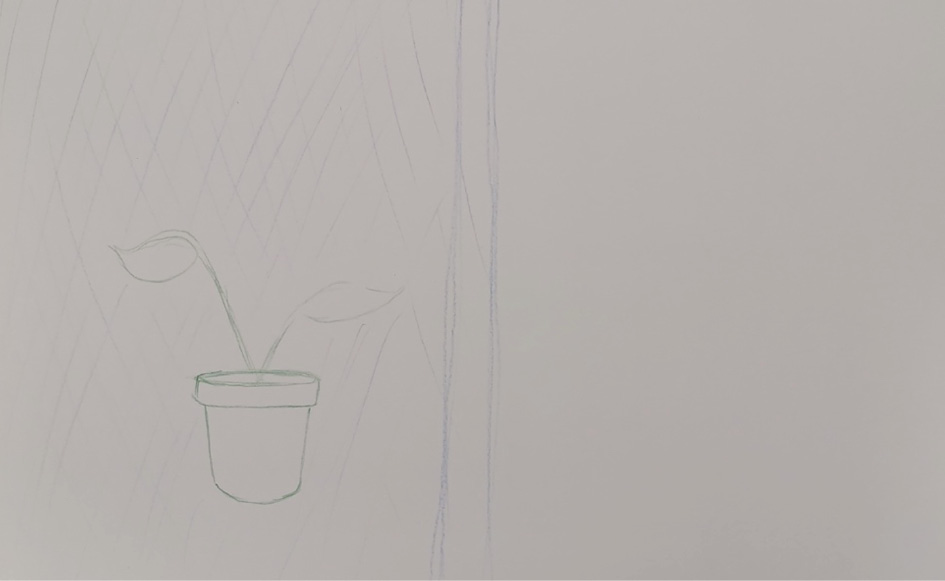

A young Asian sexual violence survivor describes the time when she was in need of support: “When I think of myself, I imagine, like, a plant (Figure 1).…But thinking back to it, if you, like, leave a plant in the shade and just ignore it. That’s kind of how I felt because I felt like I couldn’t talk to anyone, particularly about it. Because in Filipino culture, there’s a whole kind of culture around just kind of moving on and not talking about things.”

FIGURE 1 | Plant drawing by a young Asian sexual violence survivor.

I ask: “What is this?” (pointing to the vertical lines on her drawing)

She answers: “It feels like a wall. in my culture, we never really talk about those emotional things. And it’s kind of there’s a strong Catholic Christian culture in the Philippines that if you can’t fix it through any other means, you just turned to Catholicism, which I struggled with because, because of my gender and sexuality, kind of was alienating, like, religion was alienating for me. So I didn’t have that avenue to turn to. But my parents only had that avenue to offer. So it was very, it felt like they just kind of like left me alone to kind of deal with it myself, which was not particularly their fault because they didn’t know how else to deal with it. So, it kind of felt like a wall.”

Through my questions and invitations, the young Asian sexual violence survivor was welcomed into a secure and non-threatening space for free creative expression. When she crafted a metaphorical plant to delve into her complex emotions linked to the traumatic event, I entered the imaginative metaphorical realm alongside her, establishing a connection through her artwork. By highlighting the vertical lines (which she identified as a wall), I introduced relational aspects into our conversation, fostering connections not only with her but also with her artwork. With careful consideration, I prompted her to recognize the elements in her drawing and gently extended the discussion to navigate the barriers she encountered during that challenging period. Her artwork served as a tangible link between me as a researcher and her as a participant, allowing us to broach the difficult topic comfortably and safely.

At the end of the interview process with this young Asian survivor participant, I continue to utilize arts-based care to invite her to explore her growth after the traumatic event.

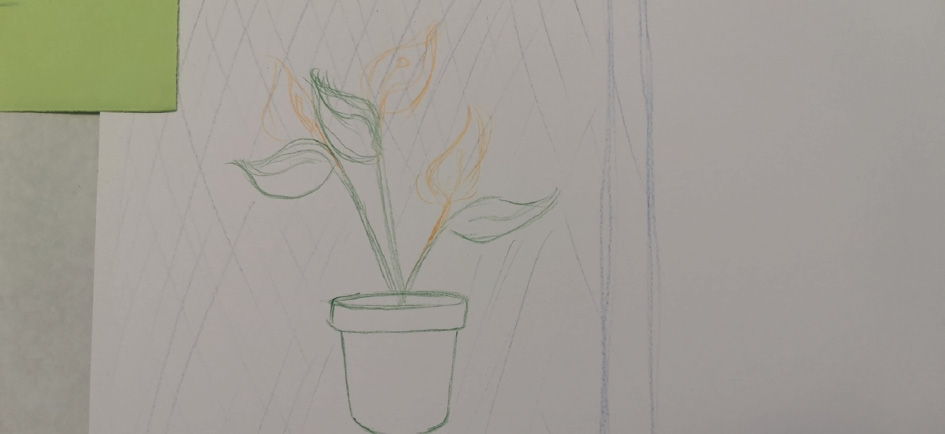

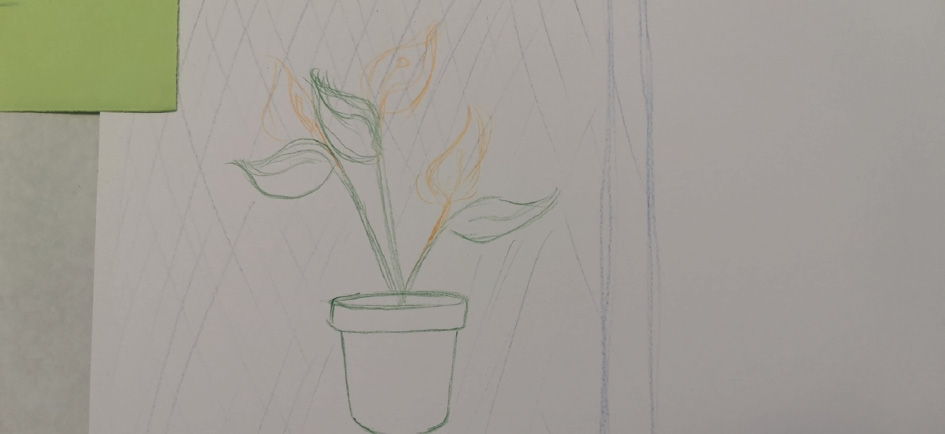

I inquire: “If we have all these kinds of beautiful support, and if you can make some change to the plant (of you), what kind of positive change do you want to make?”

She starts adding new elements to her plant drawing and says: “I wish I could talk about emotions more. Because it’s, again, it feels like I’m so disconnected from them. But that’s because I never really grew up with it being a huge aspect of how my parents raised me or how they were raised themselves. That kind of thing, there was never really a thing we practiced at home. And I get the impression it was never a thing my parents practiced at home with their own parents, and so on and so forth.…It’d be nice to add more leaves” (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2 | Plant drawing with more leaves.

I ask: “What are the leaves representing?”

She answers: “I think it would symbolize growth, the kind of growth where I can openly discuss my feelings because I can now acknowledge their existence. Going through therapy made me realize how out of touch I was with my emotions. It’s something I hadn’t even recognized before because, in my household, being out of touch with your emotions was considered normal. It’s a common trait among Asians. I used to avoid discussing topics like this.”

I say: “I notice that when you add more leaves, they become more visible and strong.”

She says: “Yeah. I think it was an issue I’ve been going through my whole life, but I only realized it was an issue after going to therapy.…Identifying who I was emotionally because prior to that, I was just kind of like…emotionally numb. I didn’t really understand what being a person with emotions was. I was not particularly helpful because I was a very emotional child. And my parents didn’t know how to deal with it. In my teen years, I was kind of raging with all these emotions.”

Establishing a secure and non-threatening environment for individuals to articulate their lived experiences is pivotal for fostering healing and enhancing mental health. Many young individuals who have experienced sexual violence trauma confront stigma, discrimination, and marginalization, making it challenging for them to find safe spaces to share their traumatic experiences without apprehension of judgment or reprisal. Arts-based methods offer an alternative for those working on this sensitive topic with vulnerable young survivors. These creative approaches extend beyond verbal communication alone. Through arts, a secure and non-threatening space can be created, enabling young sexual violence survivors to articulate profound and overwhelming emotions (Laird & Mulvihill, 2022). Integrating creative approaches and arts-based care can effectively engage children and young people in preparing for, constructing, processing, and managing their trauma narrative (Shuman et al., 2022).

Care with Cultural Appropriateness

Arts-based approaches provide a double-sided window—allowing young sexual violence survivors to express their intense emotions and enabling me as an arts-based researcher to comprehend the lived experiences and internal struggles of these young survivors (Murphy, 2001). These arts-based methods also offer a dual layer of safety—allowing young survivors to discuss challenging topics through more comfortable metaphorical language and creative expressions, also enabling me as a researcher to address sensitive research questions with gentle care. Although I am experienced in therapy and research on this sensitive topic, my upbringing in Chinese culture was heavily influenced by traditional Chinese views. I still feel uncomfortable speaking about the sensitive topic of sexuality education and sexual violence, especially within my own Asian community. Therefore, arts-based care is not only for the research participants but also for me as a researcher with an Asian ethnic-cultural background. The arts-based approach allows me to address the taboo topic through gentleness and cultural appropriateness.

I use after-session arts-making, such as poetic exploration and drawing, as self-care to process emotions arising during the interviews (Graham & Lewis, 2021). The poetic exploration throughout this article is an example of this self-care practice. That afternoon, after the conversation with the potential participant—a caregiver of a young Asian survivor, and after the peer support conversation with my therapist friend, I returned to my office. I could not focus on anything else but stuck to the comment that my friend gave me: “愛之深,痛之切! (deep love, therefore, deep pain). You are in pain because you care!” I indeed felt the pain because of my displacement experience from my immigration journey, from the stories I heard from my therapy practice and research journey, and the social connectedness with my Asian immigrant community. I also felt the regret in my heart. At that moment, I had doubts about my professionalism as a researcher.

As a researcher and an immigrant with cultural knowledge, I acknowledge that during the ethics application process, I did not invest sufficient effort into ensuring a more culturally appropriate approach. For the potential participant I described earlier, I provided an English version of the participant information sheet (PIS) with standardized (or Westernized) written language covering research aims, risks and benefits, data use and storage, privacy and confidentiality, withdrawal rights, recording and image use permissions, helpline numbers, and more. I can empathize with potential participants feeling anxious and doubtful amid the overwhelming information, especially considering the sensitive nature of this research. If I were that mother of a young survivor, burdened by shame associated with sexual violence, possessing limited English proficiency, harboring low trust in authority, and grappling with past traumatic experiences of caring for a young survivor post-event without assistance, I would also be hesitant to participate based on the information provided in the PIS. As a researcher, I recognize the importance of infusing cultural appropriateness with care right from the inception of the research journey. I must admit that I opted for a shortcut by following the standard/Westernized ethics application process and did not have the courage to design my consent with culturally sensitive care. I should have developed a culturally appropriate consent process, including a culturally appropriate PIS and invite flyer, like the Remedy Project for First Nations Communities in Australia, for this sensitive research on the Asian community (Sunderland, 2023).

As a researcher, a therapist, an immigrant, I stand,

Fighting for my community in this adopted land,

To conduct research with cultural sensitivity and grace,

In the Western academic system, leaving a lasting trace of care.

The importance of culturally sensitive practices in global health research is emphasized by past instances of power abuses stemming from colonial research methods and by the increasing integration of human rights considerations into the planning and execution of research (Finger, 2005; Pinto & Upshur, 2007). Cultural sensitivity entails thorough preparation to accommodate the varied impacts of culture on individuals’ lives throughout all facets of research conduct (Issacs, 2013; Sibbald et al., 2016). Past research indicates that a notable barrier within Asian communities is the low trust in authorities, including health, academic, and justice systems. This distrust may be rooted in past encounters with discrimination, racism, or cultural misunderstandings (Gill & Harrison, 2016; Roberts et al., 2016). Hence, crafting research for sensitive topics within the Asian community demands careful attention to cultural appropriateness to surmount this obstacle.

As a researcher, my engagement with the community extends beyond extracting research findings; it also involves giving back to my community. Drawing upon my clinical and academic experience, coupled with a genuine care for my Asian community, my research focus transcends mere findings. I aspire to effect positive changes throughout my research journey. With this intention and a caring heart, I have developed cultural competence workshops that address the support for sexual violence survivors within the Asian community. These workshops draw from the literature review conducted in the early phase of my research and my clinical experience. I have delivered these workshops within the community, aspiring to enhance community understanding of the barriers our Asian community faces when seeking help for sexual violence. This effort represents my endeavor to conduct research imbued with care and cultural appropriateness, aiming to improve social and personal connections within the Asian community. This commitment extends beyond research purposes, aligning with my genuine desire to care for my community as a researcher, therapist, and immigrant. Upon receiving a heart-shaped gift from the community following the delivery of the cultural competence workshop, my understanding of the importance of care with cultural appropriateness deepened. It emphasized the concept of care through giving rather than merely taking through my research (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3 | A heart-shaped gift.

Conclusion: Care and Careless in Sensitive Research

I reflect on the journey that began with a personal narrative, capturing a pivotal moment of realization regarding the essential care required for both my research participants and me as a researcher. By delving into the realms of care and care ethics, I have explored three layers of distinct care: the care necessary for the researcher’s various roles, care infused with creativity, and care rooted in cultural appropriateness.

As an immigrant, therapist, and researcher, the narrative unfolded in this article illuminates the dynamic interplay of roles, responsibilities, and emotional entanglements. It underscores the importance of recognizing the researcher’s multifaceted identity and the associated challenges of navigating between roles. This layer of care emphasizes the need for reflexivity and self-awareness, acknowledging the researcher’s vulnerabilities while simultaneously drawing strength from their diverse roles.

The integration of arts-based methods into the research process introduces a second layer of care—one infused with creativity. Arts-based care not only provides a unique avenue for participants to express their experiences, transcending linguistic and cultural barriers, but also allows the researcher to explore the sensitive topic with care and safety. By engaging in metaphorical and symbolic languages, participants are invited to explore the depths of their emotions through tangible artistic mediums. This layer of care extends beyond conventional approaches, fostering a deeper understanding and relational aspect of the participants’ lived experiences.

Cultural appropriateness emerges as the third layer of care for this article, embodying the ethos of “thick and thin care”—my care for my Asian community and my connected people, such as my colleagues, friends, and family in the Asian community. Addressing the specific needs of the Asian community, cultural appropriateness ensures that research processes align with the cultural nuances and sensitivities. This layer of care is fundamental in establishing trust, overcoming barriers, and providing potential research participants with a safe and culturally attuned platform to engage with sensitive research. It is a recognition of diversity and an affirmation of the importance of tailoring research practices to suit the unique cultural landscape.

However, as I draw this exploration to a close, it is imperative to highlight the significance of a particular form of care—carelessness—in sensitive research. This form of carelessness transcends mere oversight or negligence; rather, it represents a purposeful departure from entrenched research norms. It involves being indifferent to conforming to colonized research standards, like the Westernized consent process, and prioritizing the broader impact of research on the community over the research output alone. This form of carelessness advocates for a shift in focus from extracting information from the community to contributing meaningfully to it. It calls for the departure of only sticking with traditional research methodologies and challenges the conventional understanding of data while concurrently promoting innovative, creative, and culturally sensitive research methodologies.

In essence, the call for “care and carelessness” in sensitive research on the Asian community signals a paradigm shift—a departure from conventional approaches that may inadvertently perpetuate power imbalances and cultural insensitivity. It is a plea for a more thoughtful, community-centric, and ethically grounded research practice. By embracing this nuanced form of both care and carelessness, researchers can conduct compassionate, innovative, culturally sensitive, and transformative research that transcends the limitations of established norms, fostering a profound impact on both the academic landscape and the communities it seeks to understand and serve.

Ethical Considerations

The researcher gained permission to undertake this study. This study was approved by the Auckland Health Research Ethics Committee on 23/06/2023 (reference number: AH26042). The recruitment flyer includes a brief outline of the study and inclusion/exclusion criteria. The potential participants were prescreened for their eligibility for participation in this study. PISs and consent forms were sent to the potential participants. Once the participants confirmed their willingness to participate in this study, they had the chance to ask any questions they may have regarding the project or their participation. The study participants were required to sign a consent form before participating. The sessions, with participants’ consent, were audio-recorded and transcribed by the researcher. The art-making process and artworks from these sessions, with participants’ consent, were photographed and analyzed by the researcher.

Acknowledgment

The project was funded by a Lottery Health Research grant.

About the Author

Originally from China, Dr. Ying (Ingrid) Wang, a research fellow at the Centre for Arts and Social Transformation, University of Auckland, brings a unique expertise to clinical work and research. As an immigrant, Ying is dedicated to incorporating diverse perspectives into clinical practice and research, driven by her passion for enhancing well-being and promoting social justice through the transformative power of the arts. Ying supervises doctoral and master’s students in arts-based research, arts therapy, identity studies, sexuality education, and more. She has published books, articles, and book chapters and has presented her work at numerous international conferences.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: i.wang@auckland.ac.nz. ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1888-8442.

References

Allan, H. T. (2017). Emotions in the field: Research in the infertility clinic. In H. T. Allan & A. Arber (Eds.). Emotions and reflexivity in health care and social care field research (pp. 39–56). Palgrave MacMillan.

Deakin-Crick, R., Jelfs, H., Huang, S., & Wang, Q. (2012). Learning futures. Paul Hamlyn Foundation.

Fingers, K. T. (2005). Rejecting, revitalizing, and reclaiming: First nations work to set the direction of research and policy development. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 96(1), 60–63.

Fontes, L. A., & Plummer, C. (2010). Cultural issues in disclosures of child sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 19(5), 491–518.

Foynes, M. M., Platt, M., Hall, G. C. N., & Freyd, J. J. (2014). The impact of Asian values and victim-perpetrator closeness on the disclosure of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(2), 134–141.

Gill, A. K., & Harrison, K. (2016). Police responses to intimate partner sexual violence in South Asian communities. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 10(1), 446–455.

Graham, M. A., & Lewis, R. (2021). Mindfulness, self-inquiry, and artmaking. British Journal of Educational Studies, 69(4), 471–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2020.1837342.

Groenhout, R. E. (2004). Connected lives: Human nature and an ethics of care. Rowman & Littlefield.

Held, V. (2006). The ethics of care: Personal, political and global. Oxford University Press.

Isaacs, A. N. (2013). Demystifying cultural sensitivity and equity of care. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 19(1), 2.

Kleinman, S., & Copp, M. A. (1993). Emotions and fieldwork. In Qualitative research methods series, Volume 28. Sage.

Krause, F., & Boldt, J. (2017). Care in healthcare: Reflections on theory and practice. In F. Krause & J. Boldt (Eds.). Care in healthcare (pp. 51–64). Palgrave MacMillan.

Laird, L., & Mulvihill, N. (2022). Assessing the extent to which art therapy can be used with victims of childhood sexual abuse: A thematic analysis of published studies. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 31(1), 105–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2021.1918308.

Langevang, T., Resario, R., Alacovska, A., Steedman, R., Amenuke, D. A., Adjei, S. K., & Kilu, R. H. (2022). Care in creative work: Exploring the ethics and aesthetics of care through arts-based methods. Cultural Trends, 31(5), 448–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2021.2016351.

Maio, G. (2017). Fundamentals of an ethics of care. In F. Krause & J. Boldt (Eds.). Care in healthcare (pp. 51–64). Palgrave MacMillan.

Murphy, J. (2001). Art therapy with survivors of sexual abuse: Lost for words. Brunner-Routledge.

Pettersen, T. (2008). Comprehending care. Lexington Books.

Pinto, A. D., & Upshur, R. E. G. (2007). Global health ethics for students. Developing World Bioethics, 9(1), 1–10.

Pulcini, E. (2013). Care of the world: Fear, responsibility and justice in the global age. Springer.

Roberts, K. P., Qi, H., & Zhang, H. H. (2016). Challenges facing East Asian immigrant children in sexual abuse cases. Canadian Psychology, 57(4), 300–307.

Robertson, H., Chaudhary, N., & Vyas, A. (2016). Family violence and child sexual abuse among South Asians in the US. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 18(4), 921–927. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-015-0227-8.

Shuman, T., Johnson, K., Cookson, L. L., & Gilbert, N. (2022). Creative interventions for preparing and disclosing trauma narratives in group therapy for child sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 31(1), 127–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2020.1801931.

Sibbald, R., Loiseau, B., Darren, B., Raman, S. A., Dimaras, H., & Loh, L. C. (2016). Maintaining research integrity while balancing cultural sensitivity: A case study and lessons from the field. Developing World Bioethics, 16(1), 55–60.

Sunderland, N. (2023). The remedy project. In Connecting music making and indigenous health conference. University of Auckland.

Thompson, J. (2020). Towards an aesthetic of care. In A. S. Fisher & J. Thompson (Eds.). Performing care: New perspectives on socially engaged performance (pp. 36–48). Manchester University Press.

Wang, Q. (2013). Towards a systems model of coaching for learning: Empirical lessons from the secondary classroom context. International Coaching Psychology Review, 8(1), 35–51.

Wang, Q. (2016). Arts-based narrative interviewing as a dual methodological process: A participatory research method and an approach to coaching in secondary education. International Coaching Psychology Review, 11(1), 39–56.

Wang, Y. (2023). Moving between cultures through arts-based inquiry. Palgrave Macmillan.

Ward, J., & Shortt, H. (Eds.). (2020). Using arts-based research methods: Creative Approaches for research business, organisation, and humanities. Palgrave Macmillan.

Wilson, N. (2018). Creativity at work: Who cares? Towards an ethics of creativity as a structured practice of care. In L. Martin & N. Wilson (Eds.). The Palgrave handbook of creativity at work (pp. 621–647). Palgrave Macmillan.

Wolcott, D. (1988). Ethnographic research in education. In R. M. Jaeger (Ed.). Complementary methods for research in education. American Educational Research Association.