FIGURE 1 | Michal Lev (2024). Ethereal. Watercolors and pen on paper (21×17 cm).

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2024) 10(1):4–20 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2024/10/11 |

Photo Essay: Intimate Representations of Displacement

流离失所的亲密表现

Ono Academy, Israel

Abstract

This photo essay is a poignant collection of artistic expressions that reflect the emotional impact of displacement in the context of World War III. Through a series of impressionistic paintings and poetic representations, the author invites readers to witness the resilience and defiance found in artistic expression during turbulent times. The essay captures a contemplative journey over the past nine months, shedding light on the quiet, intimate moments amidst chaos and turmoil. Each painting and portrayal in this collection offers a glimpse into the emotional response to global crises, weaving together darkness and glimmers of hope. As viewers immerse themselves in this evocative essay, they are prompted to reflect on the power of art as a form of resilience in the face of adversity.

Keywords: intimacy, displacement, photo essay, World War III, reflective art

摘要

这篇摄影文章是一本凄美的艺术表现形式集,反映了第三次世界大战背景离失所的情感影响。通过一系列印象派绘画和诗意的表现,作者邀请读者见证在动荡时期艺术表达中发现的韧性和反抗。这篇文章记录了过去九个月的沉思之旅,揭示了混乱和动荡中安静、亲密的时刻。该系列中的每幅画和描绘都让我们看到了对全球危机的情感反应,将黑暗和希望的曙光交织在一起。当观众沉浸在这篇令人回味的文章中时,他们被促使反思艺术作为一种面对逆境时的复原力的力量。

关键词: 亲密关系, 位移, 摄影随笔, 第三次世界大战, 反光艺术

Introduction

This photo essay chronicles my artistic journey over the past nine months and pays homage to all who persist in creating light in the darkest of times.

Grand gestures have never been my forte or attraction. Instead, I find solace in life’s quiet moments: the unnoticed path a tear carves on a mother’s cheek, the silent amplification of sounds, the symphony of leaves falling, the delicate touch of a refugee’s hand on a cherished suitcase. These images have accumulated in my memory for months, overwhelming my sorrowful soul. These are sights no one should ever witness. Yet, they persist in my art, defying my pleas for reprieve.

History defines a world war as a conflict involving principal nations simultaneously (Merriam-Webster, 2024). By this definition, we are living in World War III—a continuous, progressive nightmare. In a world rife with turmoil, where war and chaos have become all too familiar, these artistic intimacies are born from a place of deep contemplation and emotional response to global crises. My impressionistic paintings and poetic representations, captured in this photo essay, reflect not only the darkness of our times but also the glimmers of hope and perseverance. Each stroke and color bears witness to my awe for those who continue to create, write, and contribute to the multilayered storylines of current times despite the surrounding unrest.

As you journey through this collection, I invite you to see beyond the turmoil and witness the power of artistic expression as a form of resilience and defiance.

Sleepless in Tel Aviv

In the quiet hours of dawn, I became acutely aware of my wakefulness, realizing that three hours had slipped, unnoticed. This internal dialogue, familiar and unwelcome, resumed once more, echoing the thoughts that have haunted me for too many months:

“Close your eyes, lie still, and sleep will return,” I assured myself, yet doubt crept in. Reaching for my glasses, I checked the time, a futile gesture that only confirmed my restless state.

“Ah, you’ve grown, dear,” I mused bitterly, “welcome to the age of fifty, where sleep evades you, and calm becomes a distant memory.” Frustration bubbled up—three hours of sleep was all I had managed. I turned over, placed a pillow beneath my knee, and tried to summon pleasant thoughts, but tranquility eluded me.

Even the most soothing thoughts were out of reach. In my fragmented dreams, Naama appeared. I had spoken to her grandfather a month ago, and in my dream, she cradled her baby, speaking Arabic she had learned during her preparatory year and the harrowing months of captivity. She addressed her captors—the very ones who left her grappling with the existential question of human existence.

Then, in the fluidity of dreams, Naama transformed into Noa. In a phone call with the one bearing purple hair, she declared, her voice resonating throughout Israel, “What you’re doing to me now compounds the injustice. You dragged me through hell, and now expect gratitude for the way back! Take your deranged wife, your vile son, and do not waste another moment of my time as I strive to find reasons to continue living here.”

In that instant, Noa became me. I continued speaking to the one who never truly listens, imploring, “Lower your head, you and your engines of poison and indoctrination, whose incessant drone I cannot escape. You and your band of hypocrites have robbed me of my night as well.”

Resigned, I ceased my attempts to sleep. The dawn broke, and with it came a bittersweet greeting to the day: “Good morning, Israel….”

In this watercolor painting Ethereal (Figure 1), the shoreline is bathed in a symphony of muted hues, where the delicate interplay of light and shadow breathes life into the scene. Figures, rendered as soft silhouettes, wander the beach, their forms elongated by the sun’s tender caress. The sandy expanse, imbued with warm ochres and umbers, meets the shimmering cerulean of the sea, which laps gently at the shore in an undulating dance of reflection and refraction. Each figure, a quiet testament to human presence, casts a shadow that stretches and bends, mirroring their movements and merging with the textured surface of the beach.

FIGURE 1 | Michal Lev (2024). Ethereal. Watercolors and pen on paper (21×17 cm).

The painting captures a fleeting moment, suspended in time, where the boundary between reality and dream blurs. These shadows, like whispers of their pasts, seem to carry the weight of journeys taken and homes left behind. The figures, adrift in their own contemplation, evoke a sense of searching as if the shore they tread upon is but a temporary refuge. The blending of colors and the fluidity of the scene mirror the transient nature of their existence, caught between the solidity of the land and the ever-changing tides. With its gentle washes and serene atmosphere, this painting suggests a poignant beauty of displacement. As such, it simultaneously aches and invites reflection on the quiet resilience of those who wander, seeking a place to belong.

Wandering the Land

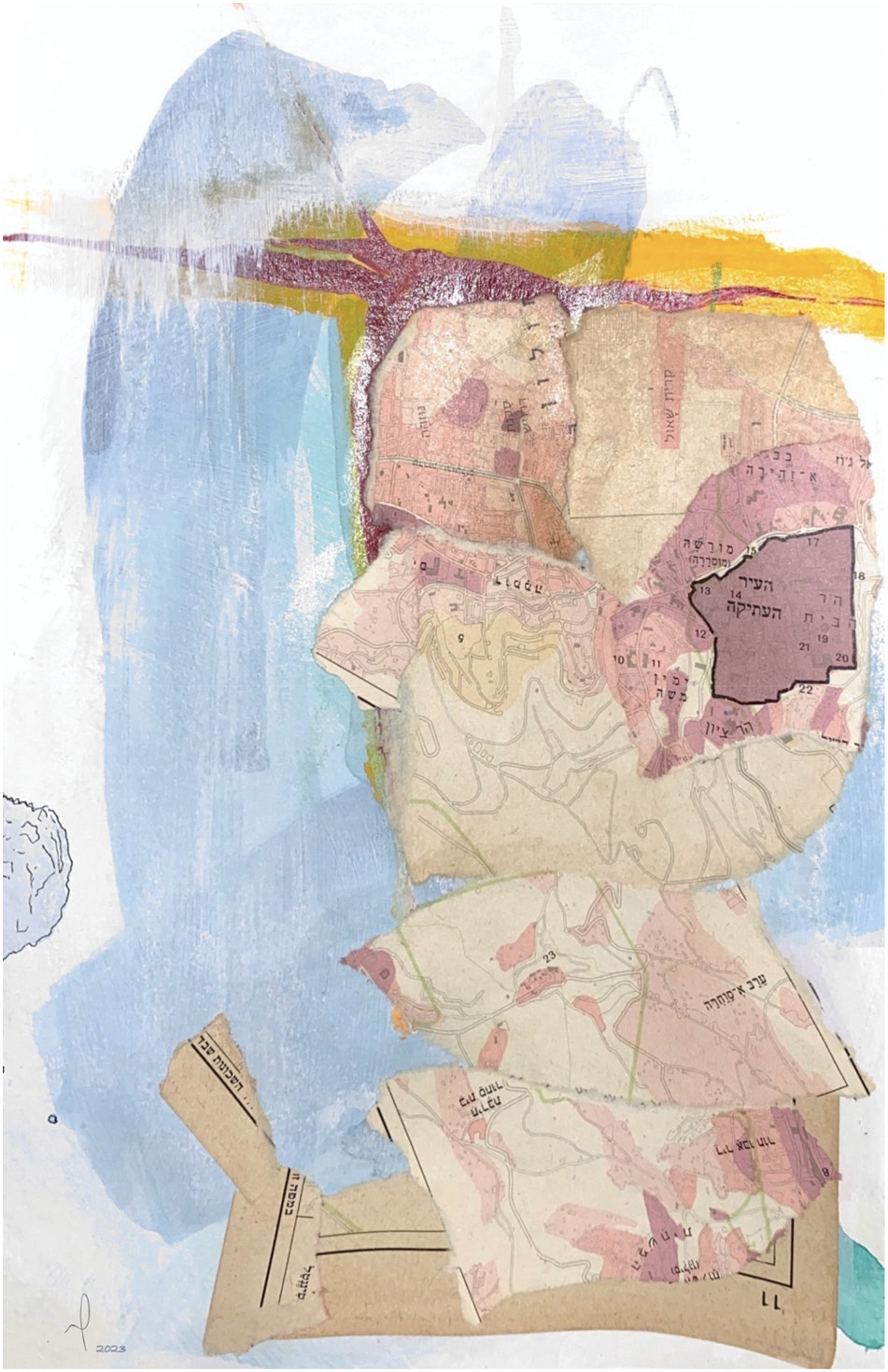

The collage painting Wandering (Figure 2) is a tapestry of textures, colors, and shapes that conjure a sense of fragmented landscapes and disrupted terrains. Torn pieces of Israeli maps command the composition, intricately layered over a softly painted backdrop of blues, greens, and yellows.

FIGURE 2 | Michal Lev (2023). Wandering. Collage (15×21 cm).

The foreground showcases several torn map pieces, some bearing discernible text and geographical markings. The background washes over with soft blues and whites, reminiscent of a sky or water, imparting a serene yet melancholic ambience. Hints of green and yellow at the top suggest land or vegetation. The colors of the fragmented maps and layered papers range from pale beige to deep pink and red, hinting at varied lands and perhaps different times or places. The maps depict diverse areas in Jerusalem with topographical features. The collage pieces are not uniformly placed; instead, they are layered and overlapped, creating a sense of dislocation. This arrangement could symbolize disrupted land or territories.

The fragmented and overlapping sections evoke the theme of displacement, depicting territories that have been divided, contested, or altered over time. Their torn edges and dis-alignment heighten the sense of dislocation, reflecting the turmoil and chaos that often accompanies displacement. Maps are instruments of navigation and ownership. Integrating them into this artwork underscores the connection to land, geography, and boundaries, while their fragmentation suggests a loss of control and belonging.

Visually, the collage is both captivating and unsettling. One is drawn into the intricate details of the map fragments while also being confronted with their arrangement’s chaos. The soft background colors contrast with the sharper lines and texts of the maps, creating a tension between tranquility and disruption.

In essence, the painting conveys a narrative of displacement through its fragmented and layered depiction of maps. It invites contemplation on the impact of losing one’s land, the changes in territories, and the emotional and physical dislocations that accompany it.

October 7, 2023—The Black Sabbath

Jarring sounds of sirens pierced the peaceful morning at 6 am. It was the Sukkot holiday, and we had just returned from our vacation in Thailand. I could not remember the last time sirens were heard in the Tel Aviv district, if ever, on Sabbath. “It must have been a technical malfunction,” I thought and turned over to the other side to continue my pleasant sleep. However, the sirens continued, insisting I should get up and wake my daughter in the next room. It starkly contrasted the usual calm of Tel Aviv so early on Sabbath, and I knew something was terribly wrong. In the next hours, the cognitive battle between reality and imagination wrestled. Through what seemed like the worst nightmare Israel has ever been through, we were hooked to the news on the television screen, between alarming sirens and running to take shelter. As the horrible day progressed, it became quite obvious that our lives had been changed for the worse. Forever.

October 8, 2023

Surprisingly, the next morning came.

I could not stay in the warm bed when my friends had been ravished, murdered, and traumatized for life. Still shaken by the uncertainty and chaos all around, I reached for my phone and texted my municipality hometown WhatsApp group: “I am organizing a minibus with therapists to go south. Will you help me with that?

The logistical coordination was done quietly. Text messages in which I was referred by activity centers, donation organizations, and thousands of volunteers—established within several hours on the day before—to the welfare social workers of the south district, who become the pillars of the mental health community, women, therapists, and heroes of the day. I understood the survivors from Kibbutz Be’eri were evacuated to a hotel in the Dead Sea.

In less than an hour from the moment I sent the message to the group, I had a paid minibus, a logistics coordinator, a brave driver, a security guard, and 16 pure souls who, like me, wanted to help in any and every way, to support, to lend a hand.

There were dozens of callers who offered help. We organized and sorted boxes of games, creative materials, clothes, blankets, and other items, while I drafted a document with guidelines for offering preliminary assistance and mental help to trauma survivors. At noon, we loaded up our gear and headed south.

I gave the briefing in the minibus. What to say, how to approach, what to focus on, what to avoid, and echoed questions that hovered over all of us—what will we find? What have these survivors seen? What kind of hell have they been through? The road south was a scene from a war movie: burnt cars on the roadsides, army trucks loaded with soldiers, and tanks with heavy artillery. I was terrified. I had never seen war up close and was privileged to avoid participating in combat or battle throughout my army service.

When we reached the hotel, the first sightings left me stunned. Teenage volunteers sorted through clothing, diaper packs, games, candy, and piles of shoes on tables that were rearranged in the lower lobby of the hotel. The evacuees were assembled in the auditorium with the surviving social workers they had known from their lives in the kibbutz. As the leader of the delegation and mission, I had to think quickly, map the area, determine the available gear and equipment, and arrange the setting for treatment and emotional help. The lower lobby was divided by wide pillars, arranging a natural secluded area, in which large round tables had been placed. We enhanced this division by placing a few screens to allow quiet and more privacy and a way of arranging art materials on the large tables. Each of us was given a name tag titled “volunteer/psychotherapist” and stationed at a specific table according to our clinical and population expertise. These tasks assisted us in helping to establish control and decreasing our anxiety.

The auditorium doors opened, and families and children slowly emerged from the hall. They were detached. Their bodies were moving; however, their eyes were hollow, and their complexion was pale. Children did not let go of their parents’ hands; every sound startled them, and they seemed completely disoriented. They were rescued by soldiers after more than 18 hours of being under siege, in which they locked themselves inside a safe room in their home with no electricity, water, or air, where they were threatened by shouting Hamas terrorists, surrounded by scents of fire and blood, horrified by guns shooting all around them. These survivors saw their loved ones molested and slaughtered in front of their eyes.

We approached them ever so gently, inviting each in their own way to sit down for a minute with one of us and tell their story—through artmaking or in words—what they went through, how they survived and got here. Some left their homes without shoes, and most left with only the shirt on their back. We helped them create a “closet” from empty bags and suitcases we had brought with us. We were all embarrassed, and although the lobby was vast, with so many people present, it was despairingly quiet.

At approximately 9:00 p.m., we arranged space for three group therapy sessions, according to age, far enough to allow for privacy and yet maintain seeing eyesight distance from their siblings and kids. I led the adult group with a colleague. For most of them, this was the first opportunity to talk to each other about what had happened and for parents to partner apart from their surviving kids.

The scenes they described echo Holocaust stories. People were burned alive in their homes, children kidnapped in front of their parents, and wives and daughters repeatedly raped, slaughtered, and raped again. Hundreds were murdered, some families were separated, and some were entirely killed. Their stories described the rescue operation in which they walked barefoot next to the bodies of friends and neighbors thrown on the burned grass while hammers were pounding in windows and gunshots deafened their ears. None of them could eat or sleep. They felt abandoned, unprotected, ashamed, and discouraged. Where was the army? Where was the leadership? When did their lives become worthless in the eyes of the prime minister? The basic trust has been expropriated, and as long as this government still rules, it could never be restored!

On our way back to our hometown, Ramat Hasharon, at 2:00 a.m., we insisted on staying awake to share and process what we had witnessed. Our words were constantly interrupted by the hardships of the road as the minibus passed police checkpoints, burnt vehicles, accidents, and tank convoys on their way south. The evil Israeli government has turned the state of Israel into a battlefield in war. We hugged and heavyheartedly parted well, carrying within ourselves the faces and stories of our brothers and sisters wherever we went.

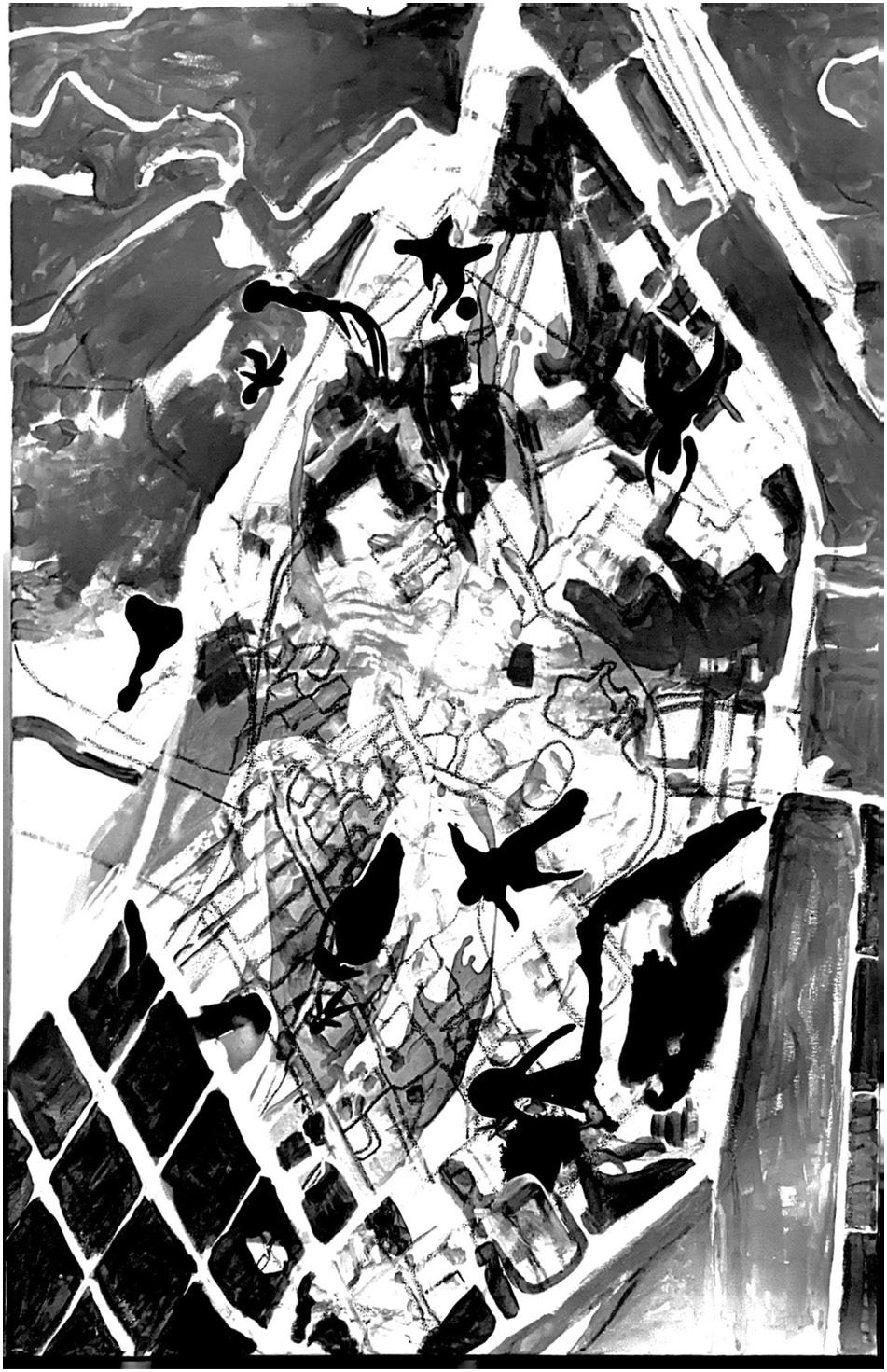

Their stories did not let me go; I could not sleep, and that night, I painted Ravished Be’eri (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3 | Michal Lev (2023). Ravished Be’eri. Acrylic on canvas (60×80 cm).

The Zone of Interest

Subtitles rise as violins play in the background—a musical piece by Micha Levi (Glazer, 2023)—heralding impending disasters. The title, bearing the film’s name, The Zone of Interest, slowly fades and dissolves into a deep, dark black, which remains for over two minutes. The experience blurs the lines between imagination and reality, accentuating that cinema is an art form (Figure 4). A mischievous game is set on our visual and hearing senses, unfolding a world of depth within this darkness, a purification of inward listening, into myself and outwards towards the objects in the space around me. I attuned to the sounds, the shifting frequencies, and simultaneously to the associations that awaken within me: a siren, an alarm, the clatter of a train, fear, shivers, solitude. These sounds are not just ambient noises but echoes of displacement, each a reminder of the fragility of place and the impermanence of change in contemporary times.

FIGURE 4 | The Zone of Interest film poster from the Cannes Festival.

Birdsong and distant human voices in a mother-tongue I do not speak as if grasping my hand, leading me to integrate the internal with the external in an almost unbearable recognition. I am confronted with the essence of displacement, where the familiar becomes foreign, and the transient constantly undermines the sense of belonging. The film tells the story of Rudolf Höss—a German SS officer and a leading contributor to using pesticides in the gas chambers for the mass extermination of Jews, also known as The Final Solution, during World War II—through the lens of his family life in their home, located in the Auschwitz ghetto. Although I was aware of the different places and times, the blackened screen invited hundreds of portraits from the terror attack of 2023 October 7, of abducted civilian Israelis, that have become permanent posters in my landscape. I picture them: innocent blue-eyed kids, red-haired babies, tall family men, slender intelligent ladies, who were brutally kidnapped on a Saturday morning on Sukkot holiday while witnessing their babies, siblings, wives, and parents slaughtered and raped in front of their eyes. Their stories intermix with testimonials of Holocaust survivors and traumatized clients in my clinic.

Again, the sound is low and muffled, creating a mounting threat, the noise of passing cars and a foreign language on the street. My reflection on the TV screen’s black glass pulls me back to here and now: “In the living room, on the floor, Saturday afternoon, hip bones, grounding.” This ordinary scene, so rooted in a specific time and place, contrasts sharply with the overwhelming sensation of anxiety that the film evokes in me. All this occurs within the first 2.21 minutes. I measured the time. After the first half-minute of the blackened picture, I pressed pause on the remote, realizing the drama that was awaiting me. For a moment, I doubted the creators’ intentions, then questioned the screen’s credibility, and confirmed to myself that this was a stroke of genius.

“Finally, a film!” I thought, sitting on the floor, leaning on the coffee table, painting my nails. In less than a minute, I understood I had to move up to the sofa, finish the topcoat, and devote the next 105 minutes to myself without interruption. This physical movement, from the floor to the sofa, mirrored the psychological shift required to fully engage with the film’s portrayal of place and displacement. I am deeply grateful to Jonathan Glazer and the other creators who conceived and brought Martin Amis’s (2014) novel to life. Ultimately, the film is more than an artistic achievement; it is a powerful exploration of displacement. It challenges me to reflect on my sense of place and how I navigate a constantly changing world (Berger, 2021). Through its oppressive atmosphere and haunting sounds, it draws me into the lived experiences of those who have been uprooted, offering a visceral understanding of what it means to be displaced. In its stark and unflinching portrayal, this film becomes a mirror to our lives, urging us to consider the fragility of our foundations and the strength required to build anew.

The war has now reached the northern district of Israel, and the heat has become heavy and dense. As if nothing could become even worse, fire is consuming the magnificent forests of the Upper Galilee and the Golan Heights. The fire engines and planes of the firefighters are prevented from reaching the area for security fears for their lives because of missiles being continuously launched from Lebanon. As an Israeli child, we would devote yearly school trips to planting trees. The devastation in watching them die is unnerving.

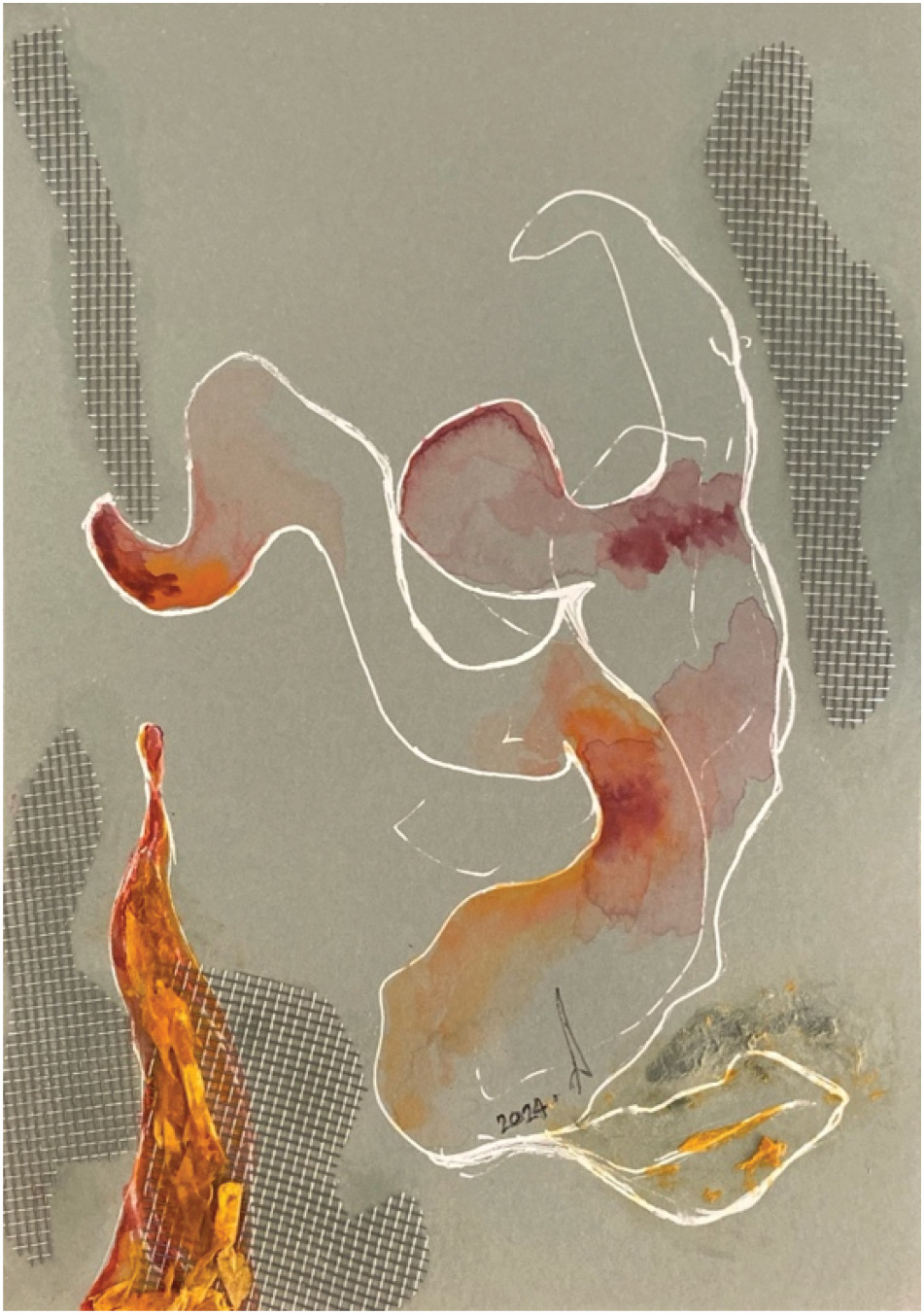

The Burning Man

This mixed-media painting presents an interplay of colors, textures, and forms, creating an immersive visual experience (Figure 5). At first glance, the fluid, organic shapes outlined in delicate white pen lines draw the eye, their sinuous forms seeming to float against a muted sage background. These abstract figures, rendered in warm hues of deep red, orange, and muted purples, convey a sense of movement and transformation as if caught in a state of perpetual flux.

FIGURE 5 | Michal Lev (2024). The Burning Man. Mixed media on paper (15×21 cm).

The textured elements, composed of mesh fragments, add a tactile dimension to the composition. These mesh pieces, positioned at various points on the paper, contrast sharply with the smooth, flowing lines of the painted forms. They evoke a sense of disruption and fragmentation, hinting at barriers or obstacles within the visual narrative. The juxtaposition of these different textures invites contemplating the tension between freedom and constraint, fluidity and rigidity (Lev, 2021). The use of color in the painting is both subtle and evocative. The warm tones of the abstract forms seem to glow against the cool, neutral background, creating a dynamic contrast that enhances the sense of depth and dimensionality. The translucence of the watercolor washes allows for a layering effect, where colors blend and interact in a delicate dance of light and shadow. These layers draw me into the painting and encourage a deeper exploration of its nuanced details.

Overall, this mixed-media painting invites a sensory experience where the interplay of color, texture, and form creates a complex, multifaceted visual narrative. It invites engagement with its aesthetic qualities (Moon, 2016) and the underlying emotions and concepts it evokes and resonates on multiple levels.

Inbetween

After a hiatus, Noam Israeli and I resumed broadcasting our radio podcast, Inbetween (https://open.spotify.com/show/2JXMJsVeOLGM8CwvIeWwQO?si=b205dda90a1c4c78) (Lev & Israeli, 2023). The podcast explored various facets of the human condition through discourse, observation, and music. Each episode, whether a standalone or part of a series, featured engaging dialogues between the moderators and, occasionally, with guests who work, write, and engage in the field. What made the program unique was the invigorating interplay between insightful conversations and carefully selected musical pieces. The program aired as a podcast from February 2022 to December 2023, recorded and broadcast from the Radiotech studio at the Technoda Center in northcentral Israel. It garnered an average of 500–1000 listens on the Radiotech website and app (Figure 6). In January 2023, it was also made available on Spotify. Since that dreadful Saturday, October 7, 2023, weeks have passed, during which songs that formed the soundtrack of our lives have taken on new interpretations, reflecting themes of bereavement, pain, and helplessness.

FIGURE 6 | Image of Inbetween podcast, Out of the Rift episode (November 2023).

One therapeutic approach to trauma emphasizes creating a continuum between life before the event, the event itself, and what follows (Springham & Huet, 2020). However, that future phase has yet to arrive. We are still entrenched in the trauma that persists daily across multiple locations and times in our world. In such unprecedented circumstances, there are no established protocols for treatment. We are tasked with developing them through our ongoing efforts.

In the episode Out of the Rift (https://open.spotify.com/episode/6L7d4sai8lUzyMhpdwOFsX?si=88191eeda5034983), broadcast on November 23, 2023, we selected songs that evoke stories from before the disaster. These lyrics may recall painful periods, yet they remind us of our resilience and survival over time. By sharing these connections, we aim to foster a sense of continuity and hope for the better days ahead for us all.

Superheroes

On February 19, 2024, the Israeli band Hatikva 6 released the single Superheroes (https://youtu.be/aYGd4HOend4?si=sjKlNyX_vD3H0AbC) (Hatikva 6, 2024) and a music video directed by Aviv Lusky. The video features the band members in various locations in Tel Aviv, with a striking moment where balloons wearing Israel Defense Forces berets are hoisted behind the band. “Hatikva” translates to “The Hope” in Hebrew and is the title of the Israeli national anthem. The band’s name is also the address of the Glickman brothers, creators of the band, 6 Hatikva Street in Ramat Hasharon.

Following are the song lyrics, with a free translation to English, and a link to the Superheroes song and video clip: https://youtu.be/aYGd4HOend4?si=sjKlNyX_vD3H0AbC

So the Bible teacher serves in Givati (a combat unit)

The language teacher in the intelligence force

The neighbor upstairs works in construction but has not been home from the reserves for over a month

The long-haired lawyer is a “Kambatzit” (operations manager)

Working shifts in the military division

Hey Bro, this senior high-tech manager, is now a sniper

On rooftops in the Gaza Strip

The branch manager in the bank

Is now a surgent in Judea and Samaria

Doron, the owner of a toy store, is a company commander

In the armoured corps.

And our beloved Idan Amedi, who usually sings in Caesarea

Is a combat engineering soldier, bravely recovering after being wounded in the heart of Gaza

Hey, it’s true—

They all look ordinary—but,

We’re a nation of Superheroes.

There’s always a soldier hidden in each of us,

Ready to save the world.

There’s the “Dan” bus driver, who is always on time,

Is now the commander of an artillery battery,

In the south, near Kibbutz Nir-Am.

The Technion student, amidst his bachelor degree

Is a captain in the 91st division in the Galilei.

The Model, is a paramedic, the electrician holds the MAG

And Yoni, the gifted saxophonist player is a fighter in Sayeret Matkal (Elite unit).

In their homes, they all have boxes with soldier uniforms and worn-out shoes.

Hey, it’s true—

They all look ordinary—but,

We’re a nation of Superheroes.

There’s always a soldier hidden in each of us,

Ready to save the world.

Figure 7 is my reflective response to an emotional gathering between a father and his soldier son.

FIGURE 7 | Michal Lev (2024). Father and Son. Acrylic on canvas (70×50 cm).

Family Home

Where is home? In what clothes? At what times of the day? Is it when I paint? When I write? My daughter, Ella, is a home for me. I am a home for words and visions; they have a place inside me. However, this place is struggling to remain stable, to keep the front door open as widely as it used to. This home has been shattered, as have many others around me, burned down into ashes. Images of homes now reside in digital albums, for the physical ones we once cherished on our shelves did not survive this man-made hurricane. According to phenomenology (Lev, 2020, 2022), if it is seen, it exists. But do they? Amidst this uncertainty, my dear friends gave birth to their first boy. I painted a homecoming gift for them (Figure 8), searching for fragments of stability and continuity in a world where the concepts of family, home, and family home have become fluid and fragile.

FIGURE 8 | Michal Lev (2023). Adam. Acrylic on canvas (40×40 cm).

I met Naama Levi’s grandfather yesterday. Naama was 19 years old when she was taken captive by the terrorists, brutally raped, and videotaped while blood stained her inner thighs. She had never loved nor known a man intimately before. We met while offering solace to a mutual friend who had lost her husband, sitting next to one another with plenty of conversation time and space. I asked him about his granddaughter’s resilience, and he was glad to have the chance to think about her this way. “She is my eldest granddaughter. I had the privilege of visiting her on her preparatory year to the army, just a couple of months before this (the terror attack) happened. Suddenly, my impression of her as a girl was transformed to see her as a mature, intelligent young lady. She is a triathlon athlete, a human-loving person, fighting for democracy and human rights; she accompanied both her parents in the 2023 demonstrations against our corrupt, extremist government. You know, she had made good Palestinian friends during that preparatory internship. It integrated the themes of peace with education and love. Ironic, isn’t it….”

The Diver

Naama came to me in my dream as a diver in the deep sea (Figure 9).

FIGURE 9 | Michal Lev (2024). The Diver. Watercolors on paper (15×21 cm).

In a burst of liquid light, a diver slices through the golden embrace of dawn, her form a fleeting silhouette against the waking sky. Her journey begins in the realm of warmth, where the sun’s early whispers paint the air in hues of hope and promise. But as she arcs gracefully downward, her figure elongates, dissolving into the cool, shadowed depths below. The waterline, a mirror of transformation, reflects a world turning inward, where light is a distant memory, and darkness wraps like a shroud.

Intertwined with the diver’s struggle is the outline of a man donning a hat, emanating a conflicting presence. Positioned near the water’s surface, facing forward, he assumes a relaxed posture with crossed legs. His right hand is nestled in his pocket, while the left remains concealed behind the diver’s crotch. Notably diminutive in comparison to the diver, his depiction conveys an impression of passivity and insignificance.

In this underwater sanctuary, time stands still. The blues swirl and mix, creating an ethereal tapestry of despair. Each brushstroke whispers of the weight that holds her down, the silent struggle beneath a serene exterior. It captures the poignant dichotomy of depression: the invisible battle fought in the depths, unseen by the world above. It is a haunting portrayal of this inner turmoil, a visual elegy to the strength it takes to face the darkness and the hope that one day, the diver will break through to the surface, gasping for breath in the light once more.

Over the past months, I have repeatedly been asked where my strength comes from. My answer is immediate and clear—I choose the positive, compassionate, and vibrant side of Israeli society.

When lack of control dominates daily reality, we can regain confidence in making small choices—do’s and don’ts.

I choose to get out of bed in the morning.

I choose what colors to wear.

I choose to limit the news on television.

I choose to leave the house and mobilize for others, facilitate an activity to a group of girls, offer my living room for a creative hour.

I choose to walk in the evening, or swim when it’s too hot.

I choose to participate in a Pilates class with the neighbours, play music, and sing (even when the songs are sad).

We have a great community and several tens of thousands of reasons to be proud—of ourselves.

We are survivors, fighters, and seekers of peace.

We should continue to hope for, believe in, and love, the human race.

As long as trees grow, and fruits ripe

I reach out to pick plums (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10 | Michal Lev (2024). Naama picking plums. Acrylic on canvas (60×80 cm).

About the Author

Michal Lev is a board-certified art therapist, supervisor, and a certified family psychotherapist. She is a faculty lecturer at the graduate art therapy program at Ono Academy–ASA in Israel, advising students in their seminar thesis and promoting art-based pedagogy and research. Dr. Lev is an Executive Committee member in the International Association for Creative Arts in Education and Therapy (IACAET). In her established private practice for couples and families, Michal incorporates expressive therapies to deal with intimacy issues and promote well-being. Her published research and presentations focus on intimacy, art-based research, and creative process-oriented pedagogy.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: michlev@gmail.com; Tel.: +972(54)6616280; Website: www.levmichal.com; ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5337-6576.

References

Amis, M. (2014). The zone of interest: a novel (first US ed.). Alfred A. Knopf.

Berger, R. (2021). Arts therapy in a changing world: Creative interdisciplinary concepts and methods for group and individual development. Nova Science. https://books.google.co.il/books?id=pCBzzgEACAAJ.

Glazer, J. (2023). The zone of interest. J. Wilson & E. Puszczyńska; A24.

Hatikva 6. (2024). Superheroes Ramat Hasharon, Amit Sagi. https://youtu.be/aYGd4HOend4?si=sjKlNyX_vD3H0AbC.

Lev, M. (2020). Art as a mediator for intimacy: Reflections of an art-based research study. Journal of Applied Arts and Health, 11(3), 299–313. DOI: 10.1386/jaah_00041_7.

Lev, M. (2021). Painting an art-based research of intimacy. In T. Yaguri & D. Merari (Eds.), Art in action: Teaching, training, and research in art therapy (pp. 229–249). Cambridge Scholars.

Lev, M. (2022). Artmaking resilience: reflections on art-based research of bereavement and grief. Creative Arts in Education and Therapy (CAET), 8(1), 126–138. DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2022/8/1.

Lev, M., & Israeli, N. (2023). Out of the rift. In Inbetween. https://open.spotify.com/episode/6L7d4sai8lUzyMhpdwOFsX?si=f0b6c757549e44ec.

Merriam-Webster. (2024). World war. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/world%20war.

Moon, C. H. (2016). Relational aesthetics and art therapy. In Approaches to art therapy (pp. 50–68). Routledge.

Springham, N., & Huet, V. (2020). Facing our shadows: Understanding harm in the arts therapies. International Journal of Art Therapy, 25(1), 5–18.