Mural Painting and Inclusive Research in Cameroon: Implementation and Impact at the University of Bamenda Campus

喀麦隆的壁画和包容性研究:在巴门达大学的实施和校园影响

Paul Ngong Animbom1, Lynn Cockburn2, Tele Djosseu Ghislain Landry1, Tafor K Ateh1, Louis Mbibeh1

1University of Bamenda, Cameroon

2University of Toronto, Canada

Abstract

This paper describes the use of mural-making as part of the knowledge mobilization activities of an international research partnership project. The mural depicts the technical and academic activities of people with disabilities in a university setting as meaningful action in inclusive research processes. The main objective of this 30-meter mural painting on a wall in the University of Bamenda was to demonstrate that inclusive research could encourage the inclusion and participation of people with disabilities in all areas of academic and professional activities of the university. A mural-making protocol was developed by the faculty and implemented by the team. It included the collection, analysis, and understanding of data on inclusion; design of drawings and the mural; wall preparation; plotting; and execution of the actual mural. The brightly colored mural now draws attention to inclusion, provides a vision of hopefulness, and complements the narrative character of inclusive education and research on campus.

Keywords: murals, knowledge mobilization, mural painting, visual expression, inclusive research, students with disabilities, university milieu

摘要

本文描述了在国际研究合作项目知识传播活动中利用壁画制作的情况。这幅壁画描绘了包容性研究过程中的残障人在大学环境中有意义的技术和学术活动。这幅 30 米长的壁画在巴门达大学墙上绘制的主要目的是证明包容性研究可以鼓励残障人士融入和参与大学学术和专业活动的所有领域。壁画制作方案由教师制定并由残障团队实施。它包括收集、分析和理解有关包容的数据;图纸和壁画的设计;墙面准备;标图;以及实际壁画的执行。这幅色彩鲜艳的壁画现在引起了人们对包容性的关注,提供了希望的愿景,并补充了校园包容性教育和研究的叙事性。

关键词: 壁画, 知识传播, 视觉表达, 包容性研究, 残障大学生, 大学环境

Disability inclusive research is a growing focus among researchers and students, including those with disabilities, in a wide range of organizations including university campuses (Abrahams et al., 2023; Tesemma & Coetzee, 2022; Wolbring & Lillywhite, 2021). Studies have identified strategies and techniques that can be used to foster the implementation of quality inclusive education and research in universities (Arcidiacono & Baucal, 2020; Friend & Bursuck, 1996; Hornby, 2015; Nelis & Pedaste, 2020; Rohland et al., 2003; Simpson, 2002). Initiatives of various sizes, such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN CRPD) (United Nations, 2006), the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (UNDP, 2022), the International Centre for Evidence in Disability (2023), and the Partnership for Inclusive Research and Learning (Mbibeh et al., 2021), demonstrate the relevance of these activities. However, there is still a lack of awareness, communication of information, and implementation of inclusive research in many universities. Participatory and emancipatory processes might be useful for improving inclusion in research on university campuses (Addo-Atuah et al., 2020; Kuper et al., 2021).

Several scholars have written about the importance of promoting inclusion in all levels of education, including universities. Inclusion is the belief or philosophy that faculty, staff, and students with disabilities should be fully integrated into their school learning communities, usually in general education classrooms, and that their instruction should be based on their human rights and abilities, not their disabilities (Cockburn et al., 2017; Mbibeh, 2013; Mezzanotte, 2022). Human rights models and the social model of disability that are now widely used can be linked back to previous work such as the 1960 United Nations Convention against Discrimination in Education (OHCHR, 1960), the 1990 World Declaration on Education for All (UNESCO, 1990), and the Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education (UNESCO et al., 1994), which all have relevance to the learning that takes place on university campuses. Many students learn better in inclusive settings where all students with diverse needs, behaviors, and abilities are included and treated equally (Carew et al., 2020; Dell’Anna et al., 2022; Kefallinou et al., 2020; Mezzanotte, 2022), although there is also evidence that programs such as dedicated resource centers and special classrooms can be beneficial for some students, particularly to ensure inclusion and to reduce violence against students with disabilities (Banks et al., 2017, 2022; United Nations Children’s Fund, 2021; World Bank, 2023). The intentions and values of inclusive education are to nurture, develop, and use the talents and strengths of all students for the betterment of everyone.

Access to higher education for students with disabilities, including students with autism, intellectual disabilities, physical disabilities, visual impairments, and hearing impairments, has been slowly but steadily increasing (Karellou, 2019; Mellifont et al., 2019; Rapp & Arndt, 2012; Talaván, 2019; Wolbring & Lillywhite, 2021). However, ongoing inequalities regarding access to university for students with disabilities remain (Abrahams et al., 2023; McCall et al., 2020). Commitments to eliminating these inequalities have been expressed by several associations and organizations, including in UNESCO’s Education 2030 agenda (UNESCO, 2015) and the “Including Disability in Education in Africa Research Unit at the University of Cape Town” (Vergunst & McKenzie, 2022).

Considering that inclusive education at universities is a key area that ensures the development of all students’ potential, interest in the study of the implementation of inclusive practices is fundamental. At the university level, research of various kinds is an integral part of learning for students. Research leads to the creation of meaningful new knowledge and to the use of existing knowledge in new and creative ways to generate innovative concepts, methodologies, and understandings (Africa Charter on Transformative Research Collaborations, 2023; Kuper et al., 2021; Walker & Boni, 2020). Researching ideas of what has been done in the past, as well as contributing to the creation of new knowledge through research, are theoretical and technical levers that contribute to the development of people and societies. Although the goal is for all students, including those living with disabilities, to have opportunities to engage with research regardless of the barriers that exist, the reality is that research continues to exclude and discriminate against persons with disabilities in the university milieu (Lorenzo et al., 2015; Milem et al., 2005).

Inclusive research is a practice that includes people with disabilities as researchers to address important and relevant issues (Callus, 2019; Mbibeh et al., 2021; Nind, 2017; Rojas-Pernia & Haya-Salmón, 2022; Stanley et al., 2019). Inclusive research considers ways that researchers with disabilities, including students and their faculty supervisors, can find avenues for their participation in research activities. Inclusive research can include examining processes of increasing the attendance, involvement, and achievements of all learners and attending to physical, social, political, economic, and cultural status to prevent exclusion. Students can be invited to participate in research as a social and meaning-making activity, to identify and participate in scholarly conversations that promote learning, and to develop scholarly identities. Inclusive research questions the consideration of people with disabilities as merely sources of data and promotes their right to participate in decisions and spaces that concern them as citizens, including academic spaces (Nind, 2017; Walmsley, 2004). It provides a learning opportunity for everyone involved, addressing complex questions in complex ways and learning how to research by engaging in the process of researching. Attention is given to the support that is needed for all members of the research team to understand inclusive practices. This type of research aims to recognize, develop, encourage, and communicate the contributions that persons with disabilities can make and can provide information that can be used by persons with disabilities and others to campaign for change (Rojas-Pernia & Haya-Salmón, 2022).

The promotion of inclusive research on campus and in campus–community partnerships have faced challenges (Kahonde, 2023; University of Toronto, n.d.), and there is still considerable resistance that maintains oppressive structures and practices in education systems, including in higher education (Leijen et al., 2021; Snijder et al., 2023; Wolbring & Lillywhite, 2021). To overcome discrimination and put in place appropriate strategies, it is important to propagate and popularize the full integration of students, faculty, and staff with disabilities.

Visual arts offer one strategy to prompt integration, inclusion, and participation. The use of artistic practice is multidimensional, facilitating creative thinking and learning, and can reflect, through a wide range of forms and color expressions, social and educational learning environments (Valentino, 2016). Artistic expression in campus spaces, including mural painting, can relay complex concepts on how to integrate, reflect, and communicate a multitude of ideas and messages related to inclusive research.

The Mural at the University of Bamenda

This article reports on the process of mural making about inclusion at the University of Bamenda, Cameroon, as part of the dissemination of an inclusive, international research project, the Partnerships for Inclusive Research and Learning (PIRL), that aimed to promote inclusive research in international development work. We produced a mural to reflect the ideas discussed above, using bright colors and local symbolism. The site where the mural is located, along a main road abutting the surrounding neighborhood, is important for communication with both the university community and those from the surrounding areas. The University of Bamenda has one other mural next to a more hidden location at another entrance to the campus.

Murals such as the new one, located in highly frequented public places, are presented as an ideal means of visually communicating messages to scores of people daily. In the implementation of the mural at the University of Bamenda, the artists used the figurative technique on 30 meters of wall. The bright colors of the mural transformed the street into a mobile viewing gallery, commentary and debate space, and a venue for picture taking. The application of color to the unpainted wall appeared like sunshine illuminating the darkness of that street, but the painted wall is also a combination of signs, symbols, and images expressing the implementation and practice of inclusive research for students with disabilities and faculty. Using this example, we aim to make intellectual ideas tangible and visible to contribute to the implementation of ideas from the PIRL Project results, and to encourage the practice of inclusive research for all viewers and members of the university community, including faculty and students with disabilities.

Mural Painting: A Tool for Communication

A mural is any piece of graphic artwork that is painted or applied directly to a wall, ceiling, or other permanent large surfaces (Marschall, 2006; Mendelson-Shwartz & Mualam, 2022). Murals are one form of communicating ideas, dreams, and messages, and they can reflect the spirit and aspirations of a specific community. Therefore, in many instances of mural making, it is essential to consider the collaboration of community members throughout the process of making a mural, from conception to completion.

By using symbols, murals often use art and imagery that communicate without words (Rose, 2001). People, regardless of their native language, create direct and indirect links with others through signs and symbols. Symbols are understood in different ways, depending on who is viewing them. Some symbols and signs hold widely shared meanings, such as a set of rings signifying a union, a dove as a sign of peace, or a skull and crossbones as a reminder of death. Others are more unique to local contexts, and outsiders require explanation to understand the intended meaning. Ideas and concepts can travel through times and civilizations to reach the audience without textual presentation. The artists symbolize the intended messages, codify them, and allow the spectator or viewer to decode and interpret the embedded messages or meanings. Mural painting makes thoughts visible, allows artists to communicate their ideas and feelings, build knowledge, and tries to make objective sense of this world (Furtado & Payne, 2023; Jaradat & Miaomiao, 2022; Mendelson-Shwartz & Mualam, 2022).

Today, murals are used as a way to express freedom and as a tool of emancipation; to create relationships between art and politics, social activism, or propaganda; and to contribute an esthetic element that fits into an environment. Some murals are created for other purposes such as advertising, attracting tourists, or simply for the pleasure of a beautiful image on a wall, as in many places the walls of urban cities are ugly and unnoticeable (Jaradat & Miaomiao, 2022). Over time murals have become cultural artefacts; therefore, murals are not only a tool for recording the history of human activity but also a tool for conveying a wide range of stories, emotions, feelings, and inner thoughts symbolically, explicitly, or in more hidden modes.

Mural art can be a powerful form of communication that is used to convey messages to a wide audience, especially when they are made in public spaces such as streets, intended to be accessible to the general population. For those who can visually see, a mural can appeal to our souls through our eyes, and they are capable of communicating feelings or emotions that words cannot communicate. Murals can beautify the drab walls of cities and uplift spirits (Marschall, 2006). They can appropriate and reclaim public spaces for those previously marginalized in the urban arena. They can reflect the cultural identity of the people of the locality by representing the preoccupations and aspirations of those who previously did not have an avenue to share their perspectives. Murals can disseminate traditional and new value systems publicly in a society in the process of transformation. Importantly, murals can function as a creative means of mass communication.

Color plays an important role in mural-making. It can elicit emotional responses, such as joy or sadness, depending on the importance of the space where it is applied and personal responses. Colors can irritate or soothe our eyes, increase our blood pressure, or suppress our appetite, and they can influence thinking and emotions, change actions, and provoke reactions (St. Clair, 2017). Therefore, the choice of color in a mural is extremely important and needs to be carefully considered.

Though mural-making is widespread in many parts of the world, it is not yet a widespread practice in Cameroon (Pucciarelli & Cantoni, 2016). Visual artists and many communities have still to recognize the importance of murals in Cameroon and still consider murals to be vandalism. Despite the importance of murals as one of the main contemporary art forms, and an art form with considerable prospects, Cameroon lags in how they can be interactive and evoke participation and engagement (Pucciarelli & Cantoni, 2016; Schemmel, 2016). In Cameroon, murals are gradually being seen as progressive, creative, and related to changes and new technologies (Pucciarelli & Cantoni, 2016; Schemmel, 2016). Park and Kovacs (2020) point out that when wall paintings are considered as a means of communicating educational messages and raising social awareness, it is necessary to make the image an intermediary interlocutor that transforms forms into a simple language for those who look at it; this complex communication is becoming evident in some places in Cameroon.

Universities have used murals for many purposes. Murals focus on the essential, hopeful, or troubling themes of everyday lives. When murals are produced with an emphasis on idea development, collaborative execution, and constructivism, or are complemented by digital technology, the result can be a very inclusive learning and art practice (Ho, 2012). Inclusive education and research in the university milieu can be addressed with murals because they can provide concrete and visual communication about relevant issues related to inclusion and change. The use of the mural as a communication element can add to scholarly work (Furtado & Payne, 2023; Segers et al., 2021).

The Process of Painting the Mural at the University of Bamenda

The mural at the University of Bamenda was part of the development of strategies for the popularization of inclusive research by faculty, students, and researchers in several locations as part of the partnership between the University of Bamenda and PIRL. The work was done by students from the Department of Performing and Visual Arts under the supervision of three faculty members.

The methodology used the techniques of creation in artistic design. The development of the mural followed the five main phases of the Tele Djosseu Ghislain Landry approach (Tele Djosseu, 2021), with several steps involved in the execution of each phase. In the first phase, the drawings were conceived and the designs sketched out. A team then selected the images to be painted. Once the selection was done, the next phase was to transfer the drawings to the wall. Finally, the mural was finished with the application of paints and protective coating. Each of these phases is described in more detail in the next section.

The Tele Djosseu Approach

The Tele Djosseu approach, developed by Tele Djosseu Ghislain Landry (2021), includes the use of traditional cultural images and understandings and the creation of contemporary artistic forms that are relevant to particular environments. The goal of this approach is to forge new visions for collectively moving forward, encourage practical actions, and improve society and communities. This creative process spans and stretches mental and physical activities from the inception of the project to the final touches on the finished product, in this case a mural on an exterior wall of the university. This structured creative process shows how an artwork can come into existence and take on its character through the stages or phases of this process. Tele Djosseu’s artistic approach draws from contemporary thinkers who are blending traditional images, such as the works of Herve Youmbi, Joseph Francis Soumegne, Pascal Kenfack, Kanté Jean Jacques, and Pascale Martine Tayou (Tele Djosseu, 2021). Their work uses different strategies to consider concepts of memory and history and their importance and impact on the creative process.

The methodology is built on the syncretism of antagonistic forms, notably from the traditional to the contemporary, or in other words, from the absolute to those that are constantly changing and emerging. It pays particular attention to the symbols used by people to establish a more common language and understanding. It addresses a combination of contrasting elements to generate a new vision and new forms that lie between traditional, native, cultural heritage, modernity, and the contemporary. In terms of method, our work borrows from sociology, anthropology, and the visual arts, and it comprises essential approaches that are summarized in the history, the culture, and the generative.

The new form and vision can be expressed through various media such as graphic pencil, charcoal, clay, paint, wood, or digital illustration, and its materialization is based on techniques used in visual arts technique. In this case of developing images, to be used for the mural, forms were derived from a syncretism of traditional and contemporary images to immerse the observer in a reality that is both local and universal. The expected works reflect the specific environment from which they are inspired. The cultural background of the artists as well as the images of their environments characterizes their final work. Our approach considers the realities of our time, the technological evolution, and the multiple forms of artistic expression that most artists encounter. It strives to remain as objective as possible and to stay in line with different contemporary practices.

The following five stages constitute the methodology: observation and analysis, graphic research, simplification of images, manipulation of images to fit the mural, and the painting process.

Observation and Analysis

Observation consists of a mental process involving vision and thought. The observations in this project were carried out by students of fine arts from the Department of Performing and Visual Arts. It consisted of identifying elements depicting or related to disability, integration in education, and inclusive research on campus. Students, under the supervision of faculty, developed an inventory of the information directly or indirectly related to PIRL’s work, including locally relevant symbols related to this work, and discussed the meanings of the work with members of the PIRL team. After researching the nature of PIRL’s work and scrutinizing their research results, we determined that our work was to build awareness and assist viewers to be more sensitized to issues of inclusion on campus. The intended outcome was to be the expression and transmission of knowledge relating to inclusion at the University of Bamenda. Given that the immediate audience of the work were people on campus and people living and passing by the mural, who were confronted with the realities of their contemporary time, our creation aimed to embrace a combination of traditional and modern forms by engaging in a reinterpretation of images adapted from the everyday forms that surround us.

This phase included the identification of the key concepts to be developed. The team considered the experiences of students with disabilities on campus, including physical, environmental, and mental aspects. Specifically, the team observed and began to analyze the attitudes of students and faculty with and without disabilities, the relationships between students and academic staff, and the impacts and contributions that students and academic staff had through various assignments and other academic activities. Analysis was made to select and identify strong ideas for a better understanding of how the drawings could communicate ideas, content, or meaning on disability-inclusive education and research in addition to locally relevant symbols.

Graphic Research

The graphic research step deals with the drawing of images, signs, and graphic symbols. In this step, our sketches considered the expression of the writing, drawing, or harmony of colors, which were identified in the observation and analysis phase. Each visual artist in the project used their particular way to reproduce the forms. These sketches could have a realistic, figurative, abstract, or symbolic tendency.

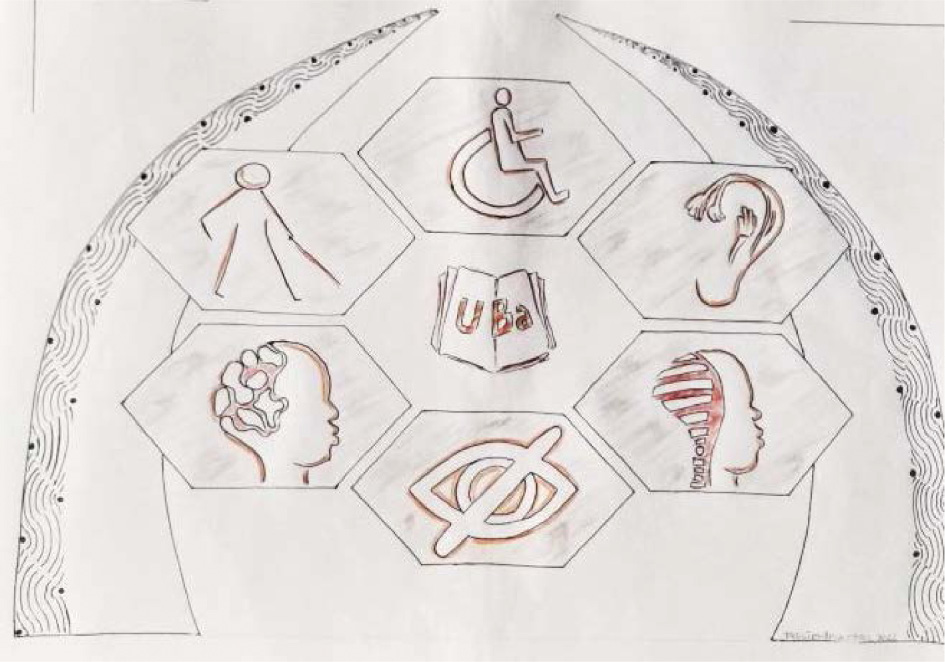

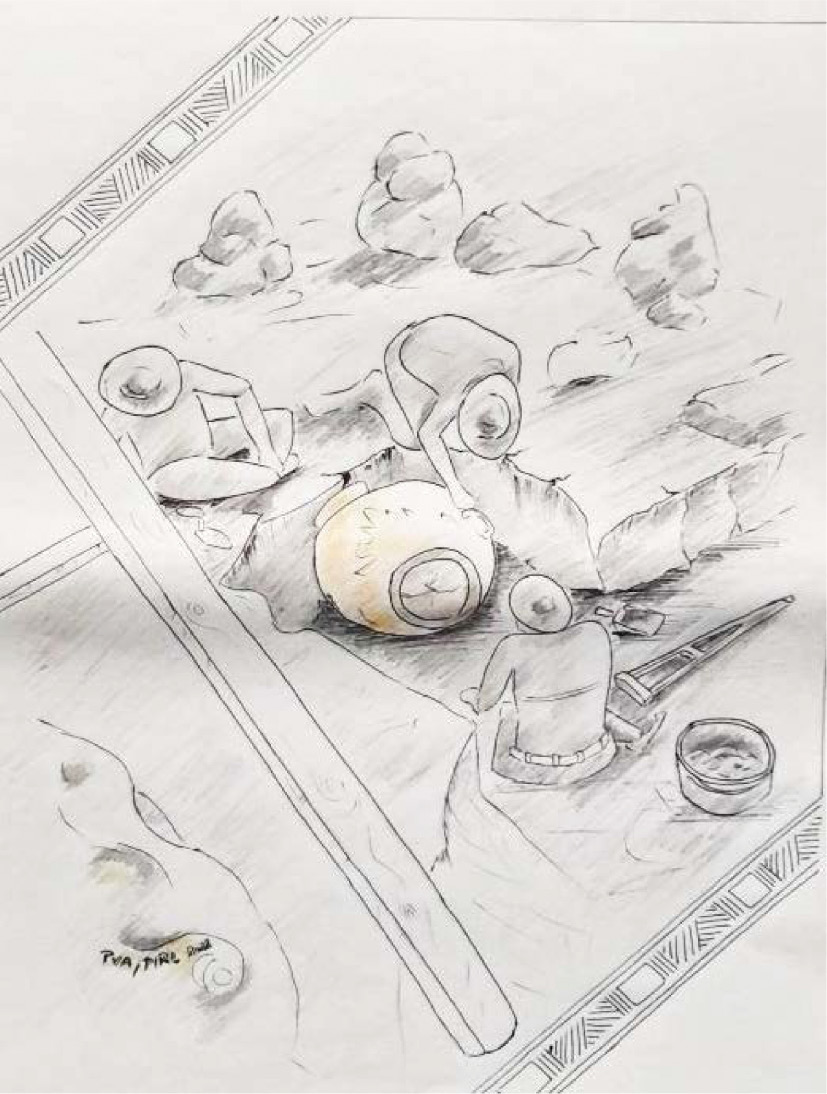

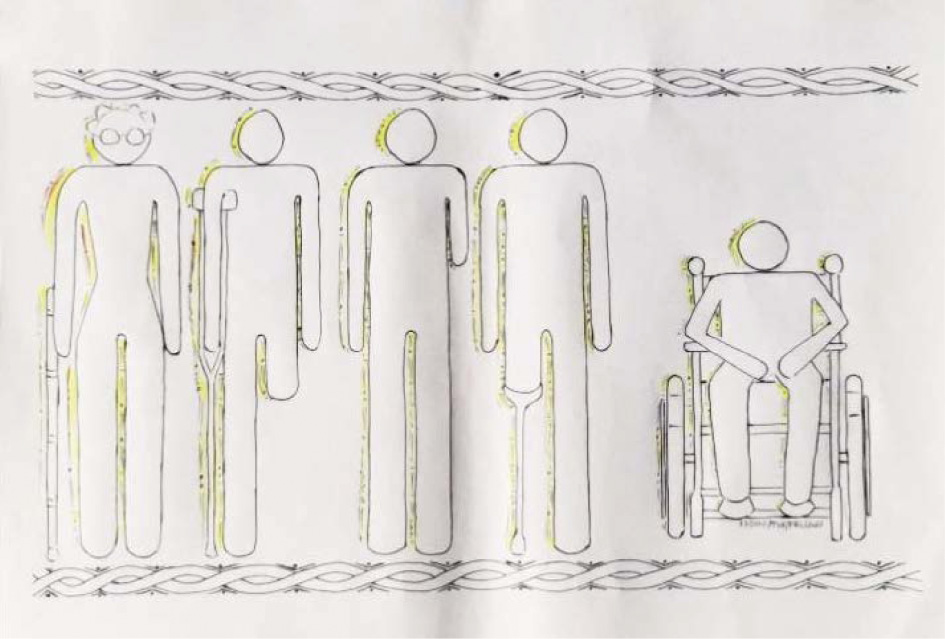

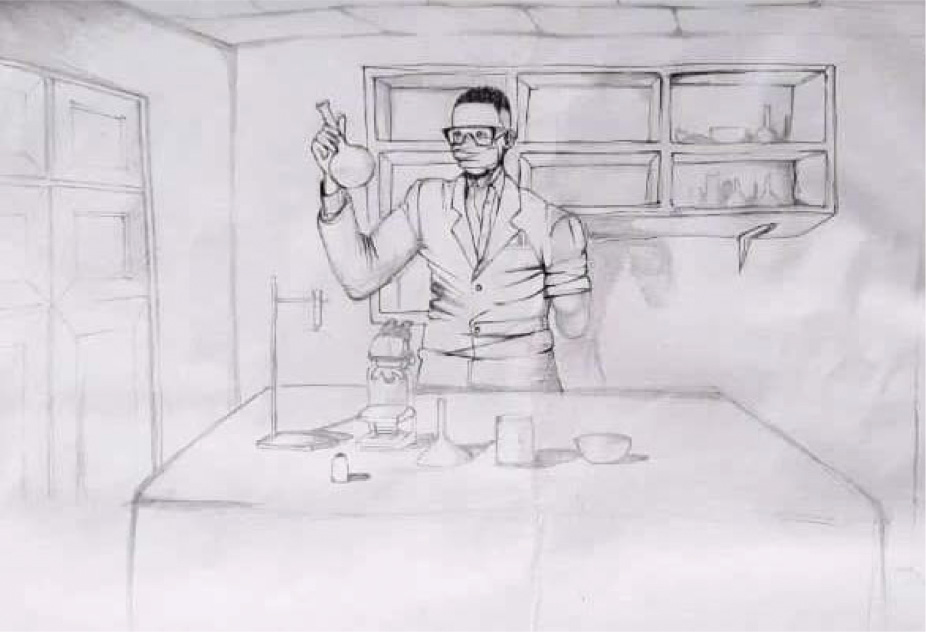

In the case of this work, we aimed to reconstitute and gather the most representative images to express inclusive research and development of disability in the context of the University of Bamenda; therefore, we wanted to include locally relevant images. Our drawings were inspired by multiple sources (including students and faculty with disabilities on campus and in the community); thus, the final products were liberal in artistic expression and embraced different forms and perspectives. We collected many images related to the main themes and subthemes identified at the initial stage of the mural process. The elements of our graphic extraction that were derived from local symbols were thus directly or indirectly related to the images in Table 1.

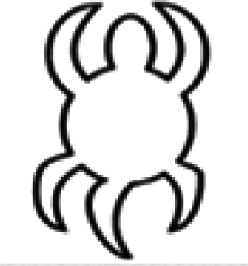

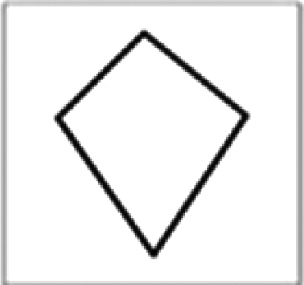

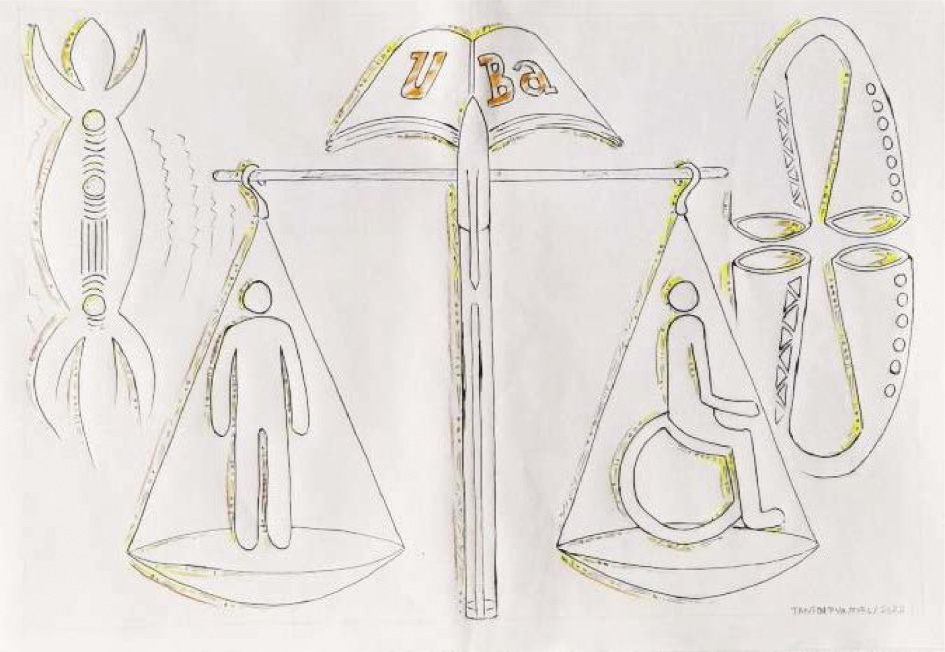

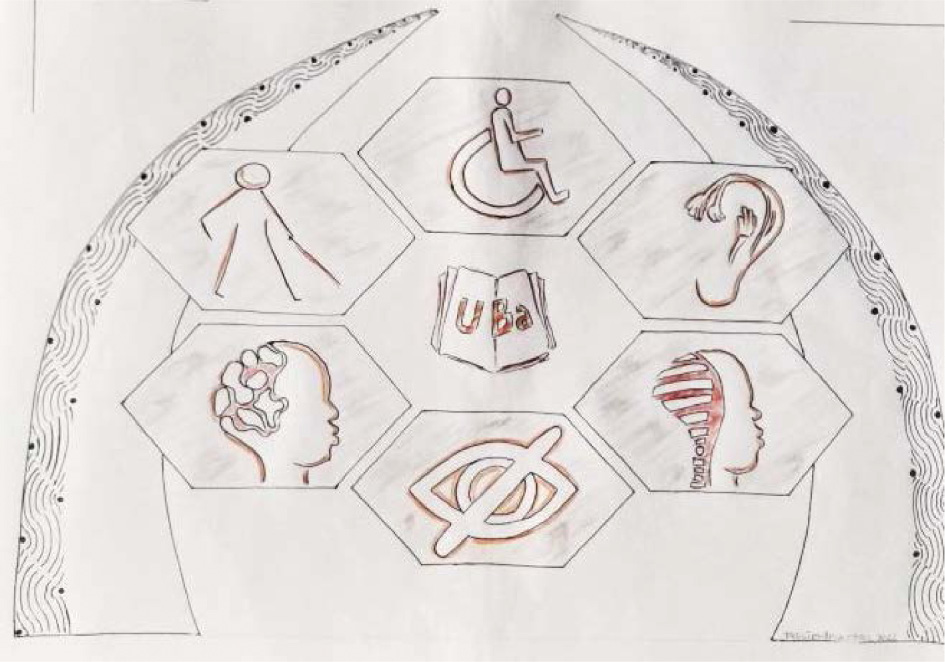

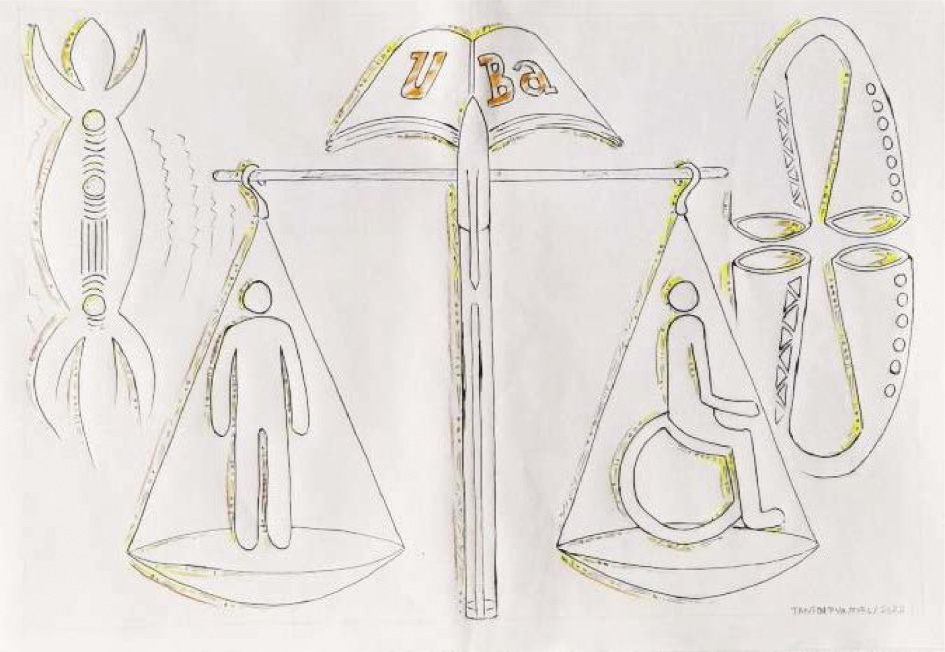

Some of the drawings which were developed following this methodology are shown Figures 1 to 7.

FIGURE 1 | Equity on inclusive research by students at the University of Bamenda.

FIGURE 2 | An image to represent inclusive research at the University of Bamenda by students with disabilities.

FIGURE 3 | A person with disability with a crutch in the middle of research at an archaeological site.

FIGURE 4 | Students with disabilities studying at the University of Bamenda.

FIGURE 5 | A student with an impaired hand working in a research laboratory.

FIGURE 6 | A research proposal presentation by a student using a wheelchair.

FIGURE 7 | A research working session chaired by a professor in a wheelchair. The rows of gongs on the sides represent the sharing of information.

During this phase, the forms of the different symbols that were going to be used in the final designs were agreed upon. At the end of this phase, there was thus a syncretism of past and present forms. As a syncretic finale, the drawings aimed to satisfy the traditional and contemporary needs of the audience, in a society in perpetual change. The forms reconstituted at the end of this work reflect elements of traditional African art in general and Cameroonian art in particular. Most especially, they reflect different forms related to disability-inclusive research at the University of Bamenda.

Simplification of Images

The third step was to rough out the intended final images, cut down the weight of too many details, and get rid of overloading elements. The roughing of images is an exercise that, beyond its innovative aspect, requires a distinguished qualification and aptitude. Determining one’s style in drawing and visual arts, in general, is not an easy task, so students were asked to differentiate their work from that of their peers for better expression. This process called on the sensitivity and emotion of each artist to achieve this differentiation. The simplification of the images, whose process consists of roughing up the original form to the desired essential lines, considers the notion of balance of the form and proportions of the isolated elements with the whole, the notions of harmony and rhythm, the properties of the new materials, and the feasibility of the medium of expression. Our creative approach in its continuation leads us to obtain a clear, precise, and captivating sketch by its expressive power.

Manipulation of Images and Final Compositions

After the process of schematization and simplification of the images, they were transformed, grouped, or merged to obtain new compositions, gradually creating what is termed a motif in this process; the motif is an artistic drawing that emerges from the themes that are identified. The process of developing a motif is that images are first grouped by theme. The grouping of images takes into account the implementation, feasibility, and material of expression. The creators are given the liberty to creatively express the ideas generated in the previous step, and they are encouraged to feel free from prescriptive classical canons about “correct” groupings or depictions that they might have picked up in learning about the creation of art. The motifs could be symmetrical or asymmetrical, static or dynamic, symbolic or realistic. The motifs created were intended to be free, objective, and rational, integrating spontaneity and distortions. The resulting works of art, apart from being decorative (just to be pleasant to the viewer), were rich in meaning, language, and emotion.

Painting Process

The work done in this step was a practical execution of the results of the manipulation of images step. The images were painted on the wall at the University of Bamenda. Public murals are painted as art for people, their functions through their visual effects are an attraction to the public. Considering that many students may not enter the University of Bamenda Art Gallery, placing the mural at a very strategic and often populated area of the campus was a good idea for better dissemination of PIRL’s results on inclusive disability research.

The painting style used during this practical stage was inspired by pop art, a style of artwork created in the UK and USA from the mid-1950s through the 1960s (Lichtenstein & Swenson, 1963). The idea was to change the perception of what art is, to break down the barriers between the so-called high art and commercial art (also known as “low art”) seen in popular culture. Pop art embraces mass production and elements from popular culture instead of trying to be unique. It is an exciting, colorful, and vibrant art form.

FIGURE 8 | Students removing dirt from the wall surface to be painted.

FIGURE 9 | With the help of a mentor, students performed the wall disinfection process.

FIGURE 10 | Applying white Pantex (paint) on the wall.

Painting the mural started with an exploration of the site to determine what was needed to do the actual painting. The students and their mentors realized that the wall was old and infected with bacteria. It was therefore important to first treat the wall accordingly. The application of a wall disinfectant was made on the entire surface, particularly the parts that were most contaminated.

Once the wall was treated, the application of white paint followed. The white paint was intended to prepare and enhance the background for the paintings to ensure good contrast with the images to be inserted.

The next action was the drawing of the images on the wall. Tracing the images with black paint and then coloring them with bright colors was part of the students’ work. It was a great pleasure for them to see their final drawings outlined on the wall. The visual stylistics of the mural were dominated by warm primary colors. This color palette was intended to express the energy, brightness, happiness, and serenity emerging from the University of Bamenda campus. Additional finishing touches were applied to the paintings by the technical staff to harmonize and add value to the work.

FIGURE 11 | Reproduction of drawings on the wall.

FIGURE 12 | Tracing the images.

FIGURE 13 | Applying colors.

FIGURE 14 | The final mural.

FIGURE 15 | Students and technical staff who participated in the painting of the mural.

Students concentrated on the approximate reproduction of preconceived designs. The lines were covered with black paint for better visibility of the drawings, and then the figures were colored in with bright colors. The shapes were then covered with colors, considering the dominant contrasts.

The effective participation of students from the Visual Arts Department of the University of Bamenda as well as some students from other departments who were passionate about painting made the work less laborious. The collaboration between students and supervisors during this practical phase enabled them to learn more about students with disabilities within the University and the strategies put in place for better inclusive research at the university campus. The result was appreciated as a visual expression of the dissemination of inclusive research strategies on the University of Bamenda campus.

Impact and Feedback about the Mural

This paper was written 1 year after the mural was completed. The mural is still very visible and in good shape. Several administrators and faculty members have commented informally on the mural and how much it adds to the university environment. Some people have stated that they would like to have more murals on the walls around the university and have encouraged the faculty to find ways to develop them.

The impact on students, including those who were involved and those who have seen it, are harder to describe. At the time, students who were involved seemed grateful for the opportunity and were proud of what they were able to accomplish. Since the completion of the mural, students have commented about the mural in passing and faculty have solicited informal comments. Some of the authors have heard from students that there might be some misunderstandings about the images of the mural, as disability awareness is low for some people, and stigma persists. Anecdotal reports are that some students have negative feelings about the colors used, stating that they feel childish and not fitting for a university setting.

We do not have formal information about the mural’s impact on students, staff, or faculty members with disabilities. Finding ways to increase understanding of the mural with students and faculty, including those with vision impairments, would be an additional goal to pursue. Understanding the full impact, interpretations, and understandings would require more follow-up work, ideally as a systematic research study. To date, we are not aware of the mural being used in teaching, which the authorship group plans to do in the future.

Conclusion

This paper describes the development of a mural focused on inclusive research at the University of Bamenda. The painting of this mural is a tangible example of art for inclusion. When seen as street art, it serves as a form of visual communication and appeals to a much wider audience as compared to the written and/or spoken word. Until the 21st century, very few higher education institutions in the world used mural painting as an outreach, collaborative, or inclusive art particularly in the context of the strategies set out by UNESCO (Institute for Statistics, 2009) as part of inclusive research in universities. Our experience indicates that mural-making can be an important addition to knowledge translation and inclusion on campuses.

The implementation of the mural is presented as a social and intellectual means for the propagation of inclusion, and particularly inclusive research, in the campus. The project was based on the PIRL Project process and results while drawing on other authors who have worked in the areas addressed in the project. The project aimed to demonstrate the inclusive research and participation of people with disabilities in all areas of academic and professional activities at the university and to make use of visual arts to make persons with disabilities and their situations visible to the public. The visual representation of the project stands as a medium for advocacy on educational and inclusive research at the University of Bamenda.

The work of developing the mural project went through many stages before the final outdoor mural was completed. This approach required a deep understanding of culture, tradition, and observation to inform the interpretation and creation of the mural. The results include representations of the symbolic elements of community identity in the region where the University of Bamenda is located. The numerous paintings that make up the mural each represent a strategic expression of the results of the means put in place for inclusive research at the university campus. Apart from the esthetics it carries, the didactic elements are rich in meaning and language, and above all communicate the message of inclusivity.

The goals of this project were successfully achieved. We will continue to emphasize that these visual expressions are not meant to replace the narrative forms of knowledge sharing about inclusive research on campus but to complement them. The use of murals such as this one at the University of Bamenda appears to be a beneficial way of involving students, faculty, and community in knowledge dissemination, and a tangible way to engage in interdisciplinary scholarly work.

Funding

We are grateful for funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Grant 890-2018-0086.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support of Professor Sunday Kometa Shende of the University of Bamenda. We acknowledge the support from the University of Bamenda, who saw the need for propagating information on inclusive research to the university community and authorised the implementation of the mural on campus. The technical contributions by Kante Jean Jacques to the painting of the mural are very much appreciated and crucial to the realisation of the project. We thank the students who were involved in this project: Timngum Preston, Tachey Innocent, Douanla Abdias Raou, Adangwa Tantoh, Ndorfor Emmanuel, Ngafor Nelissa Nwango, Yonghabi Lesly Yuli, Wanwirdzejei Matchilde, Nkeng Nembo Valery, Njamsi Godwill Ringnyuy, and Chop Bukuned Cedric. Their enthusiasm and hard work made this project come to life.

About the Authors

Paul Animbom N., PhD, is an associate professor of Therapeutic Communication, Media, and Film Studies, President, Centre for Research and Practice of Art-Related Therapy, Cameroon Pioneer Chair, Department of Performing and Visual Arts, The University of Bamenda Pioneer Member, Cameroon Academy of Young Scientists (CAYS) Post Doctoral Fellow, Department of Arts and Cultural Studies, University of Copenhagen.

https://ceforpat.com/

https://www.linkedin.com/in/paul-animbom-94b8161a/

https://ubda.academia.edu/PaulAnimbom

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Paul-Animbom

https://twitter.com/animbom

Skype: panimgo

https://www.africanbookscollective.com/books/theatrical-therapeutic-interventions-in-cameroon

https://www.amazon.com/Participatory-Theatre-Therapy-Paul-Animbom/dp/613848374X.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: panimbom@gmail.com. ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6448-4276.

Lynn Cockburn, PhD, is an occupational therapist, researcher, and educator. At the time of the work described in this paper, she was with the University of Toronto. She is now an assistant clinical professor (adjunct) at the School of Rehabilitation Science, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada. Her research interests are focused on social inclusion, disability and rehabilitation, and collaborative and participatory research, particularly in Canada and the North West Region of Cameroon. She uses a range of approaches to study how research can be part of the valued everyday activities and occupations that build communities and contribute to sustainability, peace, and justice. She is affiliated with McMaster University. ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9639-518X.

Tele Djosseu Ghislain Landry, PhD, is a lecturer in the Visual Arts Unit of the Department of Performing and Visual Arts, The University of Bamenda. He holds a PhD in Visual Arts History from the University of Yaounde 1, Cameroon. A renowned artist, he is passionate about sculpting, ceramics, drawing, and painting. He has published many scientific papers nationally and internationally.

Tafor K Ateh is a researcher and practitioner in African media studies with specialty and experience in training, research, and film and theatre production. His research interests encompass African cinema, theatre, television and media studies, film and theatre audiences, new media, transcultural film production and criticism, identity, and film aesthetics. He is a skilled versatile multimedia professional with over three decades of wide-ranging experience in creating artistic content for film, theatre, and television. He has close to two decades of experience in higher education teaching, project development, management, and implementation with excellent communication skills, including great ability for academic research. He has a track record as a freelance writer, producer and director, CAL expert, video editor, popular culture workshop facilitator, acting coach, and social and therapeutic theatre specialist. With over 80 theatre projects spanning countries in Africa, Europe, and America, he has worked on many film projects and TV shows in different capacities. He is a passionate storyteller who works with intercultural teams creating narratives that problematize cultural, developmental, environmental, and human rights issues across the globe.

Dr. Louis Mbibeh, PhD, is a researcher and academic with key research areas in disability-inclusive development, inclusive education, and language development. He has been a lecturer in the university systems in Cameroon and is currently lecturing in the University of Bamenda and internationally. He is an author and editor in many academic journals and has published widely in interdisciplinary domains.

References

Abrahams, D., Batorowicz, B., Ndaa, P., Gabriels, S., Abebe, S. M., Xu, X., & Aldersey, H. M. (2023). “I’m not asking for special treatment, i’m asking for access”: Experiences of university students with disabilities in Ghana, Ethiopia and South Africa. Disabilities, 3(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities3010009.

Addo-Atuah, J., Senhaji-Tomza, B., Ray, D., Basu, P., Loh, F.-H. (Ellen), & Owusu-Daaku, F. (2020). Global health research partnerships in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 16(11), 1614–1618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.08.015.

Africa Charter on Transformative Research Collaborations. (2023). https://parc.bristol.ac.uk/africa-charter/.

Arcidiacono, F., & Baucal, A. (2020). Towards teacher professionalization for inclusive education: Reflections from the perspective of a socio-cultural approach. Eesti Haridusteaduste Ajakiri. Estonian Journal of Education, 8(1), 26–47. https://doi.org/10.12697/eha.2020.8.1.02b.

Banks, L. M., Kelly, S. A., Kyegombe, N., Kuper, H., & Devries, K. (2017). “If he could speak, he would be able to point out who does those things to him”: Experiences of violence and access to child protection among children with disabilities in Uganda and Malawi. PLoS One, 12(9), e0183736. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183736.

Banks, L. M., Hunt, X., Kalua, K., Nindi, P., Zuurmond, M., & Shakespeare, T. (2022). ‘I might be lucky and go back to school’: Factors affecting inclusion in education for children with disabilities in rural Malawi. African Journal of Disability, 11, 981. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v11i0.981.

Callus, A.-M. (2019). Being an inclusive researcher: Seeking questions, raising answers. Disability & Society, 34(7–8), 1241–1263. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1602511.

Carew, M., Groce, N., Deluca, M., Kett, M., & Fwaga, S. (2020). The impact of an inclusive education intervention on learning outcomes for girls with disabilities within a resource-poor setting. African Journal of Disability, 9(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v9i0.555.

Cockburn, L., Hashemi, G., Noumi, C., Ritchie, A., & Skead, K. (2017). Realizing the educational rights of children with disabilities: An overview of inclusive education in Cameroon. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(6), 1–11.

Dell’Anna, S., Pellegrini, M., Ianes, D., & Vivanet, G. (2022). Learning, social, and psychological outcomes of students with moderate, severe, and complex disabilities in inclusive education: A systematic review. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 69(6), 2025–2041. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2020.1843143.

Friend, M., & Bursuck, W. (1996). Including students with special needs: A practical guide for classroom teachers. Prentice Hall/Allyn & Bacon, A Simon & Schuster Company. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED422344.

Furtado, L. S., & Payne, J. M. (2023). Inclusive creative placemaking through participatory mural design in Springfield (MA). Journal of the American Planning Association, 89(3), 310–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2022.2083008.

Ho, K. (2012). Inclusive mural painting in contemporary art education. The Visual and Performing Arts: An International Anthology, 1, 323–334. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.4617.9848.

Hornby, G. (2015). Inclusive special education: Development of a new theory for the education of children with special educational needs and disabilities. British Journal of Special Education, 42(3), 234–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12101.

Institute for Statistics, UNESCO. (2009). The 2009 UNESCO Framework for Cultural Statistics (FCS) (p. 98). UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000191061.

International Centre for Evidence in Disability. (2023). https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/research/centres/international-centre-evidence-disability.

Jaradat, M. A.-A., & Miaomiao, Y. (2022). The impact of digital technology on contemporary mural art. International Journal of Science & Engineering Development Research, 7(10), 923–927.

Kahonde, C. K. (2023). A call to give a voice to people with intellectual disabilities in Africa through inclusive research. African Journal of Disability, 12, a1127. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v12i0.1127.

Karellou, J. (2019). Enabling disability in higher education. A literature review. Journal of Disability Studies, 5(2), Article 2.

Kefallinou, A., Symeonidou, S., & Meijer, C. J. W. (2020). Understanding the value of inclusive education and its implementation: A review of the literature. PROSPECTS, 49(3), 135–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-020-09500-2.

Kuper, H., Hameed, S., Reichenberger, V., Scherer, N., Wilbur, J., Zuurmond, M., Mactaggart, I., Bright, T., & Shakespeare, T. (2021). Participatory research in disability in low- and middle-income countries: What have we learnt and what should we do? Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 23(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.16993/sjdr.814.

Leijen, Ä., Arcidiacono, F., & Baucal, A. (2021). The dilemma of inclusive education: Inclusion for some or inclusion for all. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 633066. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633066.

Lichtenstein, R., & Swenson, G. (1963). What is pop art. Art News, 62(7), 63.

Lorenzo, T., Mckenzie, J., & Ohajunwa, C. (2015). Enabling disability inclusive practices within the University of Cape Town curriculum: A case study: Original research. African Journal of Disability, 4(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v4i1.157.

Marschall, S. (2006). Murals as a popular medium of communication in South Africa. Glocal Times, 5, Article 5.

Mbibeh, L. (2013). Implementing inclusive education in Cameroon: Evidence from the Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Board. International Journal of Education, 5(1), 52–68. https://doi.org/10.5296/ije.v5i1.3279.

Mbibeh, L., Nganji, J. T., Cockburn, L. B., & and the rest of the PIRL Project Team. (2021). The PIRL Project: A case study of learning how to do disability inclusive research. Addressing Inequality through Human-Computer Interaction Workshop ACM CHI Congress, May 2021, 10.

McCall, C., Shew, A., Simmons, D. R., Paretti, M. C., & McNair, L. D. (2020). Exploring student disability and professional identity: Navigating sociocultural expectations in U.S. undergraduate civil engineering programs. Australasian Journal of Engineering Education, 25(1), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/22054952.2020.1720434.

Mellifont, D., Smith-Merry, J., Dickinson, H., Llewellyn, G., Clifton, S., Ragen, J., Raffaele, M., & Williamson, P. (2019). The ableism elephant in the academy: A study examining academia as informed by Australian scholars with lived experience. Disability & Society, 34(7–8), 1180–1199. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1602510.

Mendelson-Shwartz, E., & Mualam, N. (2022). Challenges in the creation of murals: A theoretical framework. Journal of Urban Affairs, 44(4–5), 683–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2021.1874247.

Mezzanotte, C. (2022). The social and economic rationale of inclusive education: An overview of the outcomes in education for diverse groups of students. OECD Education Working Paper No. 263. OECD. https://one.oecd.org/document/EDU/WKP(2022)1/en/pdf.

Milem, J. F., Chang, M. J., & Antonio, A. L. (2005). Making diversity work on campus: A research-based perspective. Association American Colleges and Universities. https://search.worldcat.org/title/making-diversity-work-on-campus-a-research-based-perspective/oclc/65554600.

Ndifor, B. E., Efeze, N. D., Maiwada, S., Bako, G. W., & Rafai, S. A. (2023). Identification of symbols used as motifs in Toghu production, a cultural heritage of grassland people in Cameroon. Art and Design Review, 11(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.4236/adr.2023.112013.

Nelis, P., & Pedaste, M. (2020). Kaasava hariduse mudel alushariduse kontekstis: Süstemaatiline kirjandusülevaade. Eesti Haridusteaduste Ajakiri. Estonian Journal of Education, 8(2), 138–163. https://doi.org/10.12697/eha.2020.8.2.06.

Nind, M. (2017). The practical wisdom of inclusive research. Qualitative Research, 17(3), 278–288.

OHCHR. (1960). Convention against discrimination in education. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-against-discrimination-education.

Park, H., & Kovacs, J. F. (2020). Arts-led revitalization, overtourism and community responses: Ihwa Mural Village, Seoul. Tourism Management Perspectives, 36, 100729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100729.

Pucciarelli, M., & Cantoni, L. (2016). A journey through public art in Douala: Framing the identity of New Bell neighbourhood. In Murals and Tourism (pp. 149–164). Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315547978-9/journey-public-art-douala-marta-pucciarelli-lorenzo-cantoni.

Rapp, W. H., & Arndt, K. L. (2012). Teaching everyone: An introduction to inclusive education. Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=571708.

Rohland, P., Erickson, B., Mathews, D., Roush, S. E., Quinlan, K., & Smith, A. D. (2003). Changing the Culture (CTC): A collaborative training model to create systemic change. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 17(1), 49–58.

Rojas-Pernia, S., & Haya-Salmón, I. (2022). Inclusive research and the use of visual, creative and narrative strategies in Spain. Social Sciences, 11(4), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11040154.

Rose, G. (2001). Visual methodologies: An introduction to the interpretation of visual materials. Sage. http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0657/2001269479-t.html.

Schemmel, A. (2016). Visual arts in Cameroon: A genealogy of non-formal training 1976-2014. Langaa RPCIG. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/358/monograph/book/45596.

Segers, R., Hannes, K., Heylighen, A., & Broeck, P. V. den. (2021). Exploring embodied place attachment through co-creative art trajectories: The case of Mount Murals. Social Inclusion, 9(4), 116–129. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v9i4.4403.

Simpson, A. (2002). The teachability project: Creating an accessible curriculum for students with disabilities. Planet, 6(1), 13–15. https://doi.org/10.11120/plan.2002.00060013.

Snijder, M., Steege, R., Callander, M., Wahome, M., Rahman, M. F., Apgar, M., Theobald, S., Bracken, L. J., Dean, L., Mansaray, B., Saligram, P., Garimella, S., Arthurs-Hartnett, S., Karuga, R., Mejía Artieda, A. E., Chengo, V., & Ateles, J. (2023). How are research for development programmes implementing and evaluating equitable partnerships to address power asymmetries? The European Journal of Development Research, 35(2), 351–379. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-023-00578-w.

St. Clair, K. (2017). The secret lives of color. Penguin RandomHouse.com. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/552503/the-secret-lives-of-color-by-kassia-st-clair/.

Stanley, Z., Lauretani, P., Conforti, D., Cowen, J., DuBois, D., & Renwick, R. (2019). Working to make research inclusive: Perspectives on being members of the Voices of Youths Project. Disability and Society, 34(9–10), 1660–1667. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1619232.

Talaván, N. (2019). Using subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing as an innovative pedagogical tool in the language class. International Journal of English Studies, 19(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.6018/ijes.338671.

Tele Djosseu, G. L. (2021). Création des decorations pour les édifices publics au Cameroun. Journal of Arts and Humanities, 4(2), Article 2.

Tesemma, S., & Coetzee, S. (2022). Manifestations of spatial exclusion and inclusion of people with disabilities in Africa. Disability & Society, 38, 1934–1957.

UNDP. (2022). Sustainable development goals | United Nations Development Programme. https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals.

UNESCO. (1990). World declaration on education for all (1990). OHCHR. https://www.ohchr.org/en/resources/educators/human-rights-education-training/9-world-declaration-education-all-1990.

UNESCO, World Conference on Special Needs in Education: Access and Quality, Spain. Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia Spain. Ministry of Education and Science, & UNESCO. (1994). The Salamanca statement and framework for action on special needs education. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000098427.

UNESCO. (2015). Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4. Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. https://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/education-2030-incheon-framework-for-action-implementation-of-sdg4-2016-en_2.pdf.

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities (CRPD) | Division for Inclusive Social Development (DISD). https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/crpd/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-crpd.

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2021). Seen, counted, included: Using data to shed light on the well-being of children with disabilities. UNICEF. https://data.unicef.org/resources/children-with-disabilities-report-2021/.

University of Toronto. (n.d.). 2020 Equity, diversity & inclusion report – The division of people strategy, equity & culture. Retrieved April 28, 2023, from https://people.utoronto.ca/about/reports/2020-equity-diversity-inclusion-report/.

Valentino, D. (2016). Using fine arts to implement inclusive education: Inspiring the school through a schoolwide art project. Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/10731.

Vergunst, R., & McKenzie, J. (2022). Introducing the including disability in education in Africa Research Unit at the University of Cape Town. African Journal of Disability, 11, 946. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v11i0.946.

Walker, M., & Boni, A. (2020). Participatory research, capabilities and epistemic justice: A transformative agenda for higher education / edited by Melanie Walker, Alejandra Boni (1st ed.). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56197-0.

Walmsley, J. (2004). Inclusive learning disability research: The (nondisabled) researcher’s role. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 32(2), 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.2004.00281.x.

Wolbring, G., & Lillywhite, A. (2021). Equity/equality, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) in universities: The case of disabled people. Societies, 11(2), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11020049.

World Bank. (2023). Approaches to deliver inclusive education in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/40120.