FIGURE 1 | Detail of KAA2, photomontage collection 1.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2024) 10(1):41–62 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2024/10/2 |

Studio Art Therapy Learning Ecology: Crossing Borders between Art, Education, Health, and Therapya

工作室艺术治疗学习生态学: 跨越艺术、教育、健康和治疗之间的边界

Freelance Consultant Researcher and Artist, Australia

Abstract

Studio Art Therapy is a unique learning ecology with border crossings between visual arts therapies and art studio practice, education, and health. The increased fluidity between research and practice spaces, art therapy, and arts health are elaborated as a concept, theorized with the western Deleuzoguattarian philosophy. Connections and differentiations between art making and art as therapy are revealed in a discussion of an empirical research project Art, Visual Narrative, and Wellbeing Project (AVNAW). Studio art therapy focuses on body, meaning, and healing. It speaks to the value of people making art, reflecting and talking about their making processes alone and together through an autoethnographic visual narrative approach to artmaking. The paper asks how studio visual artmaking can activate individual productive desire to adapt toward becoming well through artmaking. Care, community, belonging, and resilience are core to a studio art therapy learning ecology that responds to real-life experiences in the support of personal care and wellbeing.

Keywords: Deleuzoguattarian philosophy, studio art therapy, arts-based methods, arts health, art therapy, medical humanities, body and meaning

摘要

工作室艺术治疗是一种独特的学习生态,它跨越了视觉艺术治疗与艺术工作室实践、教育和健康之间的边界。本文以西方德勒祖古哲学为理论基础阐述研究和实践空间、艺术治疗和艺术健康之间的流动性的增强。通过对实证研究项目 "艺术、视觉叙事和安康项目" (AVNAW) 的讨论,本文揭示艺术创作和艺术治疗之间的联系和区别。工作室艺术治疗侧重于身体、意义和愈合。通过自述式视觉叙事的艺术创作方法,工作室艺术治疗强调从事艺术创作和(独自以及和他人)反思与谈论其创作过程的价值。本文亦问到如何使用工作室视觉艺术创作激活个人的富有成效的渴望,使其选择健康的生活。关怀、社区、归属感和复原力是工作室艺术治疗学习生态的核心。在现实生活中,这种学习生态以个人关怀和安康的支持作出了回应。

关键词: 德勒兹古阿塔哲学, 工作室艺术治疗, 艺术本位方式, 艺术健康, 艺术治疗, 医学人文, 身体与意义

Introduction

Studio Art Therapy is a unique learning ecology that reimagines how an educational construct of art studio learning can contribute to the field of creative arts and art therapy practices. The learning ecology has liminal spaces between the creative arts, education, and health. The concept of Studio Art Therapy is theorized within western Deleuzoguattarian philosophy. Making art means one can dwell in spaces that allow one’s subjectivity, or becoming, to constantly shift while “staying with the trouble” (Haraway, 2016) as we all seek ways to heal and live well. Artists have a long history of problem-solving, and self-reflecting through making (Grushka, 2005).

This research asks how such a studio learning ecology that folds the structures of educational and health settings can support the emergence an individual’s ways of knowing, being, and becoming (Deleuze, 2006). It reveals the benefits of visual arts inquiry methods within art studio practice and demonstrates how affective and critical self-reflective dispositions offer healing spaces of benefit to both education and health settings.

Creative arts therapies are applied in health professional fields and include expressive art applications in therapeutic practice. Arts in health and medical humanities is more broadly described as educational programs that work in partnership with health community and arts agencies (Betts & Huet, 2023). Neoliberal rhetoric in both education and health policy draws on accountability and measurement indicators dominated by a medical, educational, or socioeconomic narrative. These powerful discourses are dominated by scientific and medical statistical legitimacy and align with the medical model of a therapist and clients applying arts-based methods (Majid & Kandasamy, 2021). Seeking empirical rigor (Grebosz-Haring et al., 2022) in art health settings, I would argue, partway reveals the benefits of art-based learning. There is room to reimagine the value of the narrative and autoethnographic empirical insights forged within the arts as a fundamental skill for all individuals in building their adaptive resilient futures. Research reveals the benefits and understandings of how the arts work across cognitive, embodied, and somatic ways of knowing. The benefits of making art within the illness–health narrative from a connecting philosophical lens, toward knowing and becoming for adaptive living are the focus of this article.

Art, Body, and Healing: A Narrative and Autoethnographic Project

The Art, Visual Narrative, and Wellbeing Project (AVNAW) (Grushka et al., 2014) reported in this article lives in the fluid or border territory between health, living, wellbeing, learning, healing, and narrative autoethnographic arts practice. The project was co-researched with the Autoimmune Resource and Research Centre at John Hunter Hospital, Newcastle, NSW, Australia. The participants had a range of autoimmune illnesses including lupus, scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis, and Sjögren’s syndrome. Participants without autoimmune illness were also a part of the project. It gathered information on how making art, using visual self-narratives, supported both their social and personal wellbeing.

The research project sought to build on the known importance of creating narratives or stories to understand our human lives connecting art, the body, and the mind (McQuillan, 2000). It asked what is unique about visual narrative approaches in a studio learning environment to personal resilience and health? The research project explored the case studies of the participants who elected to work with visual narratives to help them manage change or disruption in life events, such as loss and illness. It was an interdisciplinary interventionist approach that applied both scientific health measures and drew on philosophical psychology and qualitative methodological approaches. The studio learning spaces of the project were facilitated by an artist educator, who helped the participants create visual narratives as an autoethnographic method to inquire into their own subjectivities as a form of becoming (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987). It focuses on how connections were made between making personal visual narratives, adaptive ideas, and somatic insights as felt and expressed images (Shen et al., 2018). It will refer to the participants KAA1 and KAA2, both women between the ages of 40 and 50 years who are artists living with autoimmune illness. This retelling re-represents the empirical health measures and qualitative evidence first gathered and reported in the project through a Deleuzoguattarian philosophical lens.

The AVNAW project attracted mostly women and reflected the overall prevalence of females living with autoimmune illness. Autoimmune illness brings with it an altered immune function and heightened inflammatory responses to normal events with stress linked to somatization as a key marker (Ilchmann-Diounou & Menard, 2020). Other life experiences and associations to the illness as triggers are not proven, but the participants living with autoimmune illness experienced ongoing pain, increased infection, and a range of inflammatory illnesses. Embodiment and somatization are relationally linked concepts with links to philosophical psychology. We possess a feeling body, we make meaning within sociocultural contexts, and healing is linked to our experience of knowing how all our senses inform our being (Morujão & Leite, 2023). All experience is qualitative, performative, and autoethnographically positioned (Denzin, 2018). It can include everyday events such as time, day, weather, place, spaces, events, friendships, emotions, and physical illness or wellness. With a focus on the workshops, the project offered opportunities for personal affective learning, social support, friendships, networking, and self-reflection. All the participants initially volunteered because they had a strong interest in visual arts or wanted to be supported in their journey by being involved in artmaking with others.

An artist/educator facilitating the workshops gave her definition of her art practice: “I don’t do self-portraits: my practice is me.” Artists as self-reflective learners can interrogate and deal with the complexities of society and their feeling selves via many narrative styles including the self-portrait. The self-portrait carries greater insights than the objective/hermeneutic observer portrait created by an artist. Frida Kahlo (https://www.fridakahlo.org/) was the impetus and artistic beginning for the self-narrative journeying of the participants. The world-famous painter represented her own illness and pain over her lifetime through self-portraits but also through a rich world of metaphoric symbols that carried personal meanings of significance. Participants were asked to share their personal objects of significance and created a “Leftovers of your life” box of memorabilia. Visual narratives using collage materials, advertisements, old books, etc., and copies of photographs from the participants’ home albums or new photos filled the “Leftovers of your life” box. They were the starting point for affective and associative metaphoric explorations that became collages working across many mediums. These objects/images were combined with drawing, texture, textiles, and painting media. The workshop methods are fully described in the article Visual narratives performing and transforming people living with autoimmune illness: A pilot case study (Grushka et al., 2014). Art studio therapy is applied to best describe the learning environment of the project. The space was an art studio, the facilitator an arts educator, and the creative focus was on the feeling, knowing self.

Literature Review

There is a need to reestablish the centrality of the creative arts as fundamental to the human experience, acknowledging its essential contribution to communities and an individual’s sense of belonging and being (Dissanayake, 2009, 2014). The concept of art studio therapy has been selected as it represents the opportunity to rethink how the creative arts, in particular visual studio thinking, offer a valuable learning ecology. Ecologies as a contemporary paradigm describes how subjectivities or identities relationally evolve within complex living and adapting social systems (Horl, 2017). A Deleuzoguattarian view of studio learning embeds the concept of autopoiesis (Thompson, 2004) and the more recent concept of ecopoiesis based on human theory and practice (Levine, 2022). Autopoiesis within a studio art therapy environment is understood as using artmaking for adapting, living, and feeling within a social, mental, and health sense-making space. Autopoiesis occurs from a network of organizing components that sustain our being beyond the original reference to Varela’s biological ecologies (Guattari, 1989, p. 101). Guattari’s Three Ecologies (1989) are a techno, social, and semiotic ecological condition where media and technologies dominate the environment. Guattari’s three ecologies have structural complexities such as architectural spaces, economic relations, social structures, communication, technologies and practices, and cultural activity. In the creation of healing ecologies, consideration should be given to all the adaptive spaces our complexity of ecologies inhabit. Artists, with their material sensitivities, Guattari argues, are the most profound ecologists (p. 8) able to embrace an ethico-aesthetic within his three ecologies. An art studio ecology develops a range dispositions or habits of mind that benefit all learners, such as observation, attention to the feeling self, persistence, observing, reflecting, envisaging possibilities, and engaging with the familiar and unfamiliar (Hetland et al., 2014). It is a learning space where cognition is affectively grounded. Representations, or imaging acts embed reasoning or being and knowing and are performed through the complexity and our feeling and expressive self (Damasio, 2021).

Phenomenal experiences are relational and are constituted by contributions from “our material world, the body, the brain, the mind” (DeLanda, 2022, p. 5). The philosophers Deleuze and Guattari (1987) and Barad (2007) speak to affect, agency, identities, and storying that link through the concept of past–present–future becoming and space–time–mattering, respectively. Barad (2007) describes this kind of reflective knowing as “an appreciation of the intertwining of ethics, knowing, and being” (p. 185). The neuroscientist Damasio (2021) also speaks to feeling and knowing together as cognition. They are linked to an individual’s unique mind–time. Feelings as affective responses are both mental and physical and “they are extraordinary enablers of adaptive and creative actions” (Damasio, 2021, p. 191). Deleuze speaks to stress and the diseases of the self (Deleuze, 1990). The knowing self is impacted by the affective or embodied attention we give to our perceptions, events, and their causal relationships when experiencing or recalling both self and “other” narratives.

The boundaries between the structural borders of arts and health practices are present in studio art therapy and acknowledged in the AVNAW project. The project considers how this learning ecology supported the participants’ beliefs and behaviors as they reside in an individual’s desire and their intuiting imaging acts. Being and becoming, enacted through artmaking, allows for encounters with aesthetic borderlines and multiple assemblages that dwell within the confines of the body and sociocultural structures (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987; dell’Agnese & Szary, 2015). Artmaking therefore can involve a rethinking of the relationships and connections between things. Representations, particularly in images, addressing the “who am I question?” through autoethnographic encounters may accommodate new imagining possibilities. Images can constantly undergo differencing, remain unstable, and inhabit liminal spaces. Images are held within living usage and are unique within individual sense making (Deleuze, 2004). Artmaking is a processual folding and unfolding of imaging acts and implies differentiating according to need (Deleuze, 2006). We can imagine and adapt as we explore personal and sociocultural borders. We can find limitless ways to represent ourselves.

Studio artmaking is powered by affective knowing and being and may be a collaborative mode of art therapy (Betts & Huet, 2023). Arts-based methods (Barone & Eisner, 2012; Finley, 2008), of which artmaking is one, can interrupt and transform what may appear to be fixed spaces or fixed borders through the physical, symbolic, and metaphoric world of reassembled and manipulated images (Giudice & Giubilaro, 2015). The assembled self also contains narrative binaries with strong borders such as mother–daughter and wellness–illness. These narratives carry intense performative energies. But it is possible to intervene, resist, and disrupt such binaries through imaginative processes. Making art can be seen as a space of such resistance where one can “de-territorise, cut the border and carry it away or re-territorise and stabilise it” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987, p. 88). Within a studio art therapy construct, the learning is performative and the artworks support personal and social action inquiry and creative reasoning (Rose et al., 2021). The focus on autobiographical encounters can find the participant working in surprising ways as they fold past–present and future becoming(s). It offers thinking, interpretive, and healing tools that support the emergence of pieced-together assemblages of self.

Results and Findings

The results in this paper will focus on the connections found between the narrative and autoethnographic visual and verbal qualitative data gathered in the AVNAW. The qualitative data was classified into four categories and recorded in the AVNAW pilot case study (n=18). It had three groups of participants: artists (n=5) and non-artists (n=8) with an autoimmune illness and artists without an autoimmune illness (n=5). The participants were recruited through the Autoimmune Research and Resource Centre (ARRC) regional volunteers register. It will refer specifically to the participants KAA1 and KAA2 living with autoimmune illness. This re-telling re-represents the empirical health measures and qualitative evidence first gathered and reported in the project through a Deleuzoguattarian philosophical lens. The qualitative data had four dimensions and the General health and functional assessment was a pre and post assessment collected over 3 months (see Table 1).

TABLE 1 | Health and Wellbeing Mixed Method Data and Analysis Focus

| Qualitative data | Analysis focus |

|---|---|

| (1) Narrative and autoethnographic data: images, artworks, reflective journals. | Identification of significant life events, creativity, adaptability insights, and wellbeing through images and words. |

| (2) Semi-structured interviews of study participants. | Correlations of narratives and actions. Identifying “troubling” at the borders between wellness and illness. |

| (3) Semi-structured interviews with participant-nominated significant others. | Correlations between spaces and viewpoints on life events that shaped participant’s beliefs, mind–time, creativity, adaptability insights, and wellbeing. |

| (4) Artmaking and Wellbeing Diary, ×4 talk-aloud sessions, self-administered wellbeing surveys, and tracking feelings throughout the artmaking events. The recorded voices extended the Artmaking diary entries at home. | Correlations between behaviors, feelings and artmaking or emotion–cognition interactions over time. Behavior mapping, moods, and feelings of wellness or illness to identify themes and shifts in emotional and physical wellbeing over time. |

| (5) General health and functional assessment in relation to illness was carried out on the participants’ pre- and post-project artmaking interventions and at the commencement and conclusion of the project. Quality of life and standard health assessments administered by an ARRC researcher. | Tracking shifts in health and measuring health functionality and mobility by the ARRC staff member over time. |

The synthesis of the data findings applied a montage method of editing, blending, overlapping, or a piecing together of knowledge, meanings, and aesthetic nuances revealed through the qualitative methods (Denzin and Lincoln, 2005). The data seeks to capture artmaking as a processual and embodied way of knowing. It speaks to our continued becoming, where past, present, and future imaginings collide (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). Becoming is an ongoing liminal journeying, which reflects the complexity and movement of human life. It is linked directly to one’s unique capacities to be adaptive, to manage stress, and to respond to change as they impact our health. Health and education policy are currently measured by the application of economic measures that contribute to the undervaluing of the Arts by applying the rhetoric of health–wellbeing, behavioral, vocational, and competency measures’ link to economic outcomes across both settings. Philosophical insights offer a way to reenter the landscape of the medical health illness–wellness paradigm measured predominantly via the doctor–patient relationship.

Creating Active Assemblages through Artmaking: Connecting Body, Feeling, and Visual Storytelling

The focused analysis reported in this article speaks to the findings of two of the artist participants, KAA1 and KAA2. It speaks to the how they embraced learning in a studio environment and applied visual art methods both in the structured research workshops and then extended their thinking and making tools overtime at home. Both KAA1 and KAA2 are women between the ages of 40 and 50 years who are living with autoimmune illness. The visual narratives, their autobiological contexts and content, reflective interviews, and the keeping of an Artmaking and Wellbeing Diary plus recording ×4 talk-aloud sessions are analyzed and combined within a visual and verbal narrative analysis. The analysis of the arts-based narrative data and the diary entries revealed the relationality of the participants’ reflections and how their images speak to the participants’ feeling voices. Both the imaged narratives and reflective diaries speak to their ethico-onto-epistemology (Barad, 2007; Barraclough, 2018) or a personal ethics of reflective and resilient being and knowing emergent within the participants’ making. The data speaks to what Haraway (2016) terms “thinking with, storytelling” and “it matters what thoughts think thoughts: it matters what stories tell stories” (p. 39). We know and think about our world through telling stories through and with other worlds, knowledges, thinkings, and yearnings.

The analysis also revealed how imaged metaphor also linked to storied knowledge and each participant’s being and becoming (Barraclough, 2018; Lakoff & Johnson, 1980). Personal objects, once simply an unconscious part of the participants’ life world, took on significant symbolic and metaphoric meanings. The objects and the body–world narratives were analyzed to identify the crossing-over strategies the participants used to link their artmaking narratives with their health experiences (Kearns, 1997). It presents connections between philosophical ideas and the creative journeying toward knowing self as an assemblage of events, experiences, and feelings in a synthesized and nonlinear way, paralleling experiential embodied cognition. The connecting images and personal reflections bring forth themes and reveal how the participants felt and thought through visual storytelling. This moving between and across the analysis and findings speaks to the complexity and interconnectedness of narrative approaches in research. The following headings speak to the major findings of the qualitative study.

Studio Art Therapy: An Ecology for Individual Learning

Both the personal and institutional life worlds of the participants are part of the wider world of social histories and our situated knowledge. Participant KAA2 developed the idea of memorabilia to communicate the multiplicities of her identities: mother, wife, daughter, friend, etc. (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). The following extracts from her artist statements reveal their potency.

Forty

I took this photo just on turning 40…. Past and present, people in my life, their photos, their trinkets, the camera, and the memories these items trigger, all keep my heart open and my love of life strong. I’m lucky to be forty and to have such a fortunate life.

Then speaking of her artwork

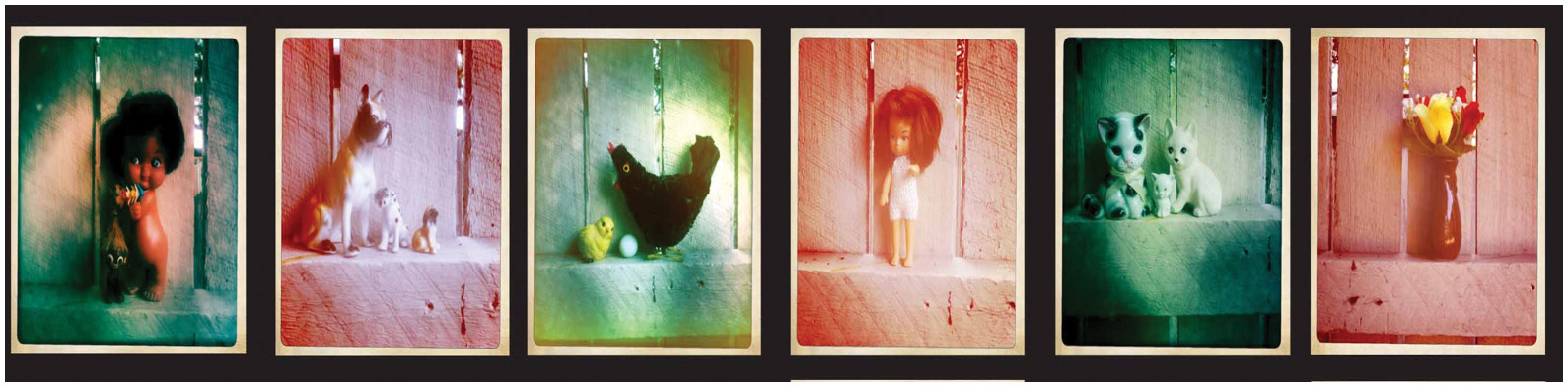

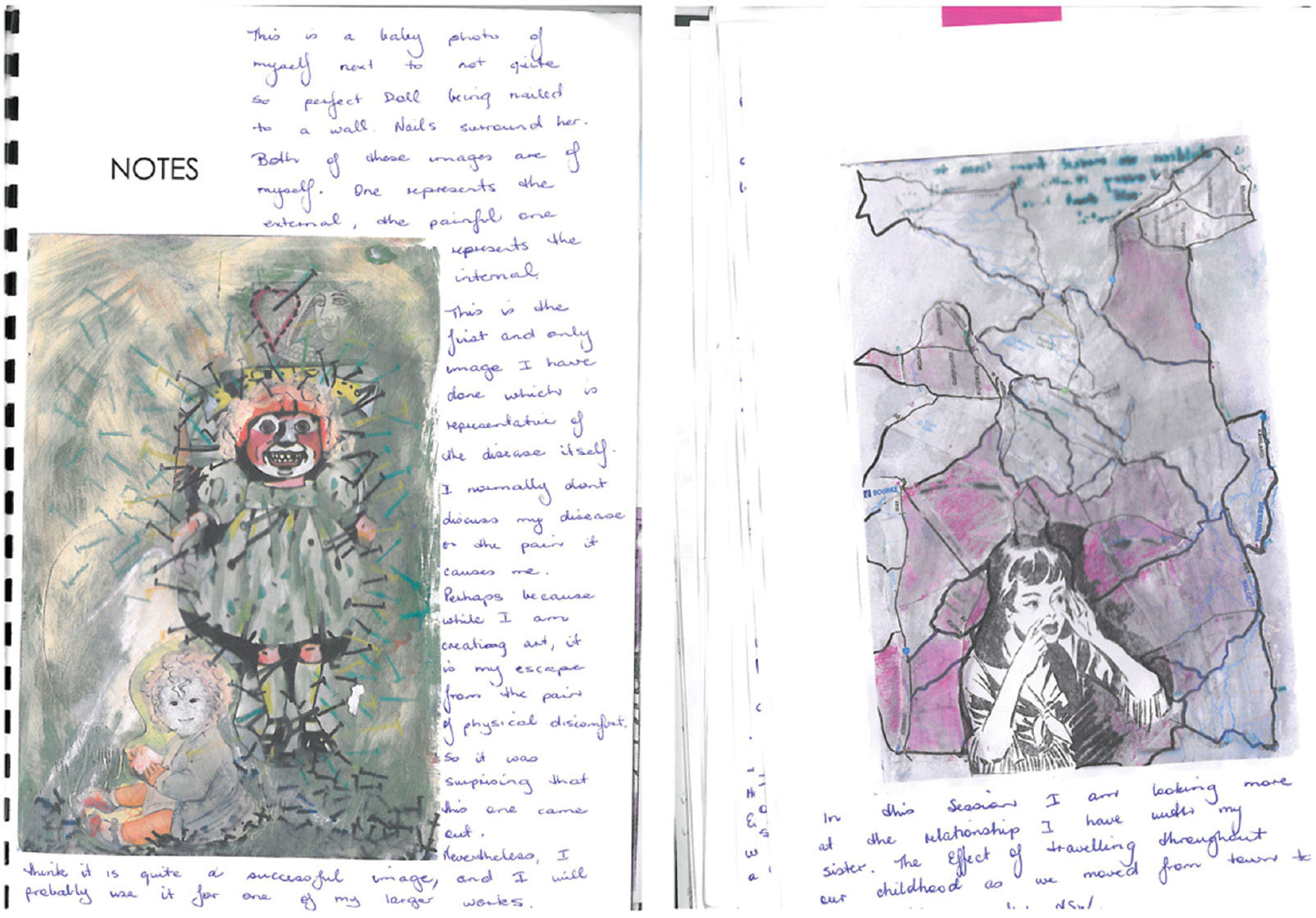

Collection 1

These photos are taken with my iPhone… items are bits and pieces I have bought from the markets…. Things that make me think “my Nana had one like that.” Trash to some, treasures to others. Trinkets and dolls triggering beautiful memories and my love of the past. This is my ode to “stuff,” “stuff” and things that cheer up my house and my soul that form elements of her photomontage (Figure 1, below).

FIGURE 1 | Detail of KAA2, photomontage collection 1.

Her storied words echo one of the main themes in the studio art therapy learning ecology: That artmaking nurtures narrative identities and has complex cognitive mechanisms or art practices that link to life and family histories, careers, and the longing to be well or to heal. Ideas, feelings, images, and metaphors are continuously juxtaposed by artists when they make art and recount their intentions when artmaking.

KAA2 speaks to the personal power and impact of learning in an art studio when at school:

At high school and with an art teacher that was just so encouraging and let us just express ourselves… it’s your choice… it was kind of a freedom and I felt normal when I was [making art].

KAA1’s daughter as nominated significant other speaks about her mother in an exit interview. She describes the impact of learning in such an environment for her artist mother. She states:

I guess at first, I just thought it was because she was doing something that she loved but also it seems to be empowering for her…. I guess there’s many reasons why she enjoys making the art itself. Expressing her views of different things through her art and it’s just given her that outlet I guess that she never had before it.

Narratives as Immanence: Folding through Artmaking, Intensities, Time, and Self

A studio art therapy learning environment has immanence, the potential for participants to become. It emerges through the concepts of duration, multiplicities, balances, interactions, and intensities or feelings between bodies without organs, such as hospitals, health systems, policies, work/life structures, and the experiential embodied world of the individual, their lives, their choices, and their artmaking. In Deleuzoguattarian philosophy intensities are energy—energy can bring forth difference and potentialities. Both in the workshops and continued at home, the participants worked with autoethnographic visual narratives where they were encouraged to be inspired by the detail of the mundane and familiar. The workshops would bring into focus new ideas and materials; working at home allowed the participants to extend the ideas begun when working together.

The reflective art diary was designed to support and increase participant engagement. A diary is personal, it does not have to be shared. It allows the participants to open new personal spaces that merge as feelings, connected to ideas. Together they began to stimulate more adaptive and reflective approaches about their own narrative researching. Both spaces, the studio art therapy workshops and the art diaries, are temporal spaces of feeling and ideas, intellectual work. The power of a reflective art diary is that it can track past ideas and bring them into the present in the generation of new ideas. This process is well documented as having iterative, hermeneutic, and creative potential. It is a sense making space that gives intuitive access to deeper levels of meaning. It brings forth new multiple subjectivities that can be continuously folded from the inside (perceived events and feelings) and re-represented on the outside as new imaged realities and experiences, new ways of knowing, and new metaphors. This process can also fold in the reverse, with many possibilities, such as the impact of a doctor’s visit or family event in changing a dominant narrative (Deleuze, 2006). Artmaking spaces are an ecology that is filled with a montage of all preexisting components, such as knowing self as mother, friend, or living with autoimmune illness, remembering hospitals, feeling pain, all with adaptive potential.

Keeping a diary facilitates reflective inquiry over time, and the artist diaries are standard practice and used often by artists and art educators and their students to track emergent ideas or resurfaced feelings. They also allow retrospective commentary on artwork in progress (Tokolahi, 2010). In the AVNAW project, the participants were asked to reflect on, talk about, draw, and write during their artmaking sessions while working in the studio or at home. Together, the datasets speak to the participants journeying across time, bringing together past, present, and future into one dialogue or visual assemblage. Participants KAA1 and KAA2 live with autoimmune illness and acknowledge they use their art to support wellbeing.

Reflecting about time passing, KAA2 speaks to her artmaking:

This first piece of artwork is coming along well. I’ve really been enjoying putting it together… It’s been really relaxing, and the time’s been flying. I would be here all night, very easily, without realizing how much time’s going by…. I haven’t been worrying about anything else. I’ve just been really getting into it.

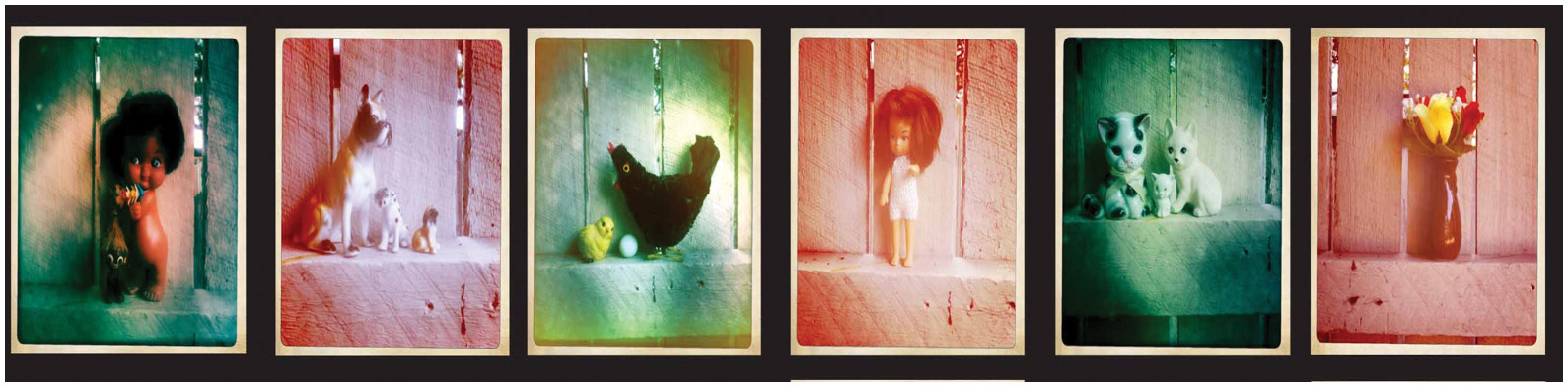

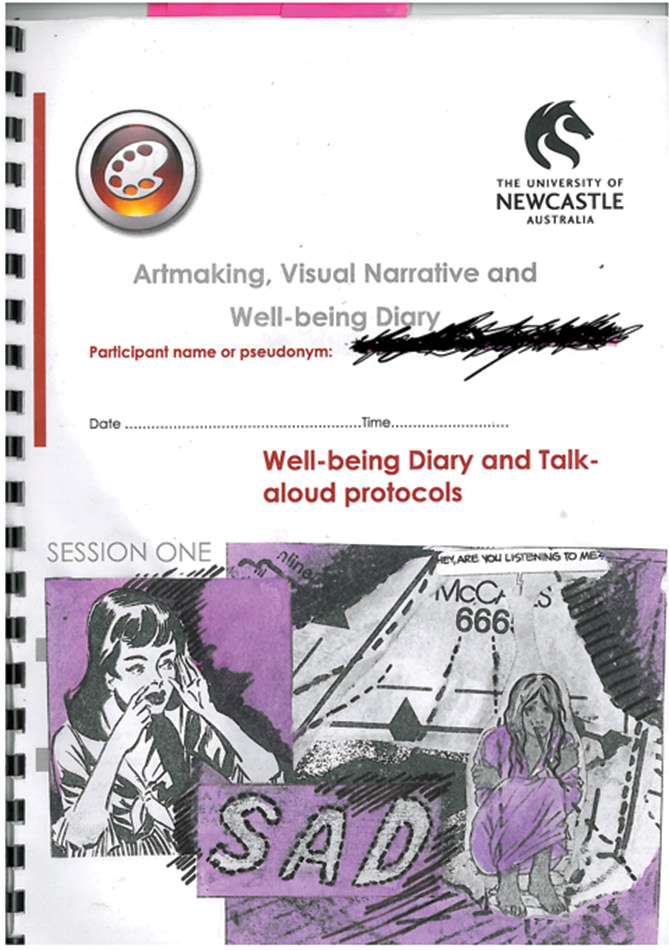

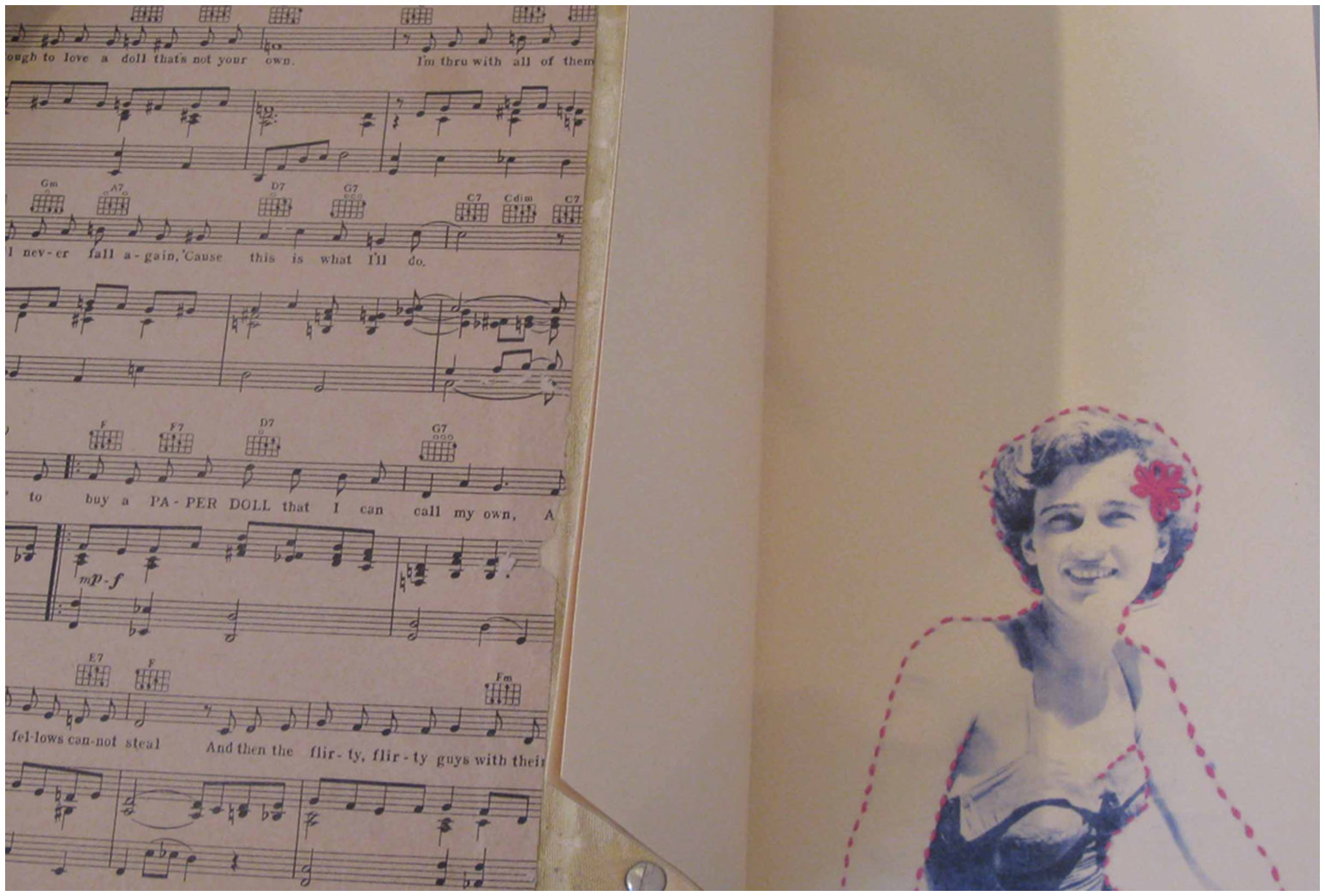

Figure 2 is the front page of KAA1’s diary produced across the studio art intervention period. The title page images are a collage of herself, her mother, and being “sad.” The diary images tell the story of her journey with her sister back in time, a narrative about revisiting her childhood, where the family traveled and resettled a lot from place to place across the countryside during their formative years. The characters are symbolic paper-dolls created across time; they can be reworked and reconfigured within her narratives. Figure 3 (extract from text below) describes how she approaches making her art.

FIGURE 2 | Art diary title page (KAA1).

FIGURE 3 | Art diary page (KAA1).

I don’t begin the artworks with a finished product in mind…. I select and cut…then paste. I do this while I can feel a “flare” starting in my body…but I make art…[it’s an] unconscious act…. I am not fully conscious of what I have done until I snap back out of it.

Figure 4 includes a self-portrait, as child and as doll (paper-doll). Dolls can be puppets, paper dolls can be destroyed, paper dolls can be made. Nails surround the doll. The doll is an external construct of KAA1. It represents her constant pain. The child is her inner self; in this image she is longing for the past, her pain-free innocence. Both exist together. In the present, while she makes art “it is my escape from the pain, my physical discomfort.” She makes an image, her body feels, and healing emerges, albeit transitory, temporary pain relief.

FIGURE 4 | Art diary page (KAA1).

Figure 4 also includes an example of her journeying with her sister. In this image she has compressed and overlaid travel and time; it speaks to being together with her sister. The sisters are defined by a narrative of an unsettled childhood, yet the subject is her mother.

Durations, Time, and Feelings

For Deleuze & Guattari (1987), Deleuze (1993), the experiential world is constituted by our past and present and is folded as we intuit and perform our future becoming. Deleuze (2006) talks to the concept of the fold as offering infinite possibilities in the movement from the inside to the outside. When art is created, the artist invents new possibilities through interconnections and new assemblages and folds life experiences (Grushka et al., 2019; Semetsky, 2010). Artmaking is processual and can be infinitely employed in an ongoing folding and refolding. The application of the concept of the fold allows us to think about how past events and experiences can be retrieved and thus support our understanding of how meanings shift overtime. They then have the potential to be seen as new or a re-presentation of events and past feelings within the folds. By folding one can challenge your own established narrated life, critique the fictional constructs presented by others, such as social and medical “other” narratives, and continue to refold and reveal a diverse array of narrative viewpoints. The feeling body controls how and what is folded (Damasio, 2021). Figure 5 (below is by KAA1). It is a cropped image of a page from her art diary. Here she has folded the narrative of herself and her mother through the words of a song. The metaphor that has surfaced is the “paper doll.” The characters can be cut out along the red dotted line. The paper-doll can carry many narratives across time, the paper-doll has experienced pain, been manipulated by others, and other narratives. There is a desire to find another “paper-doll one that I can call my own.”

FIGURE 5 | Art diary page (KAA1).

Creating artworks and an art diary has significance as it allows one to be able to work with duration, movement in time, forward and backward, and it is a powerful reflective tool. This skill can be adapted into all situations, all subject matters, and all contexts. The studio art therapy workshops, facilitated by the artist educator, became an exemplar for workshop members to apply in their own making practices alone and together. All were encouraged to listen actively and support others in questioning assumptions about their well-worn narratives of illness and wellness, to the possibilities of finding new “healing” narratives. For many participants, autoimmune symptoms are hidden and enduring, such as long-term pain felt by themselves and experienced by families. As a result, the socially constructed narratives told by others also impact on their own recalling of past events and actively shape future narrative identities. All the participants in this study with autoimmune illness felt regret and were sorry that their illness had impacted those closest to them. In the identification of new narratives there was an opportunity for a retelling of “other” narratives beyond the well-rehearsed illness narratives. Personal narratives were used by participants to explore and resolve conflicts or dilemmas, to answer questions about their own identities, or to create narratives of resilience.

Mapping Time and Feelings

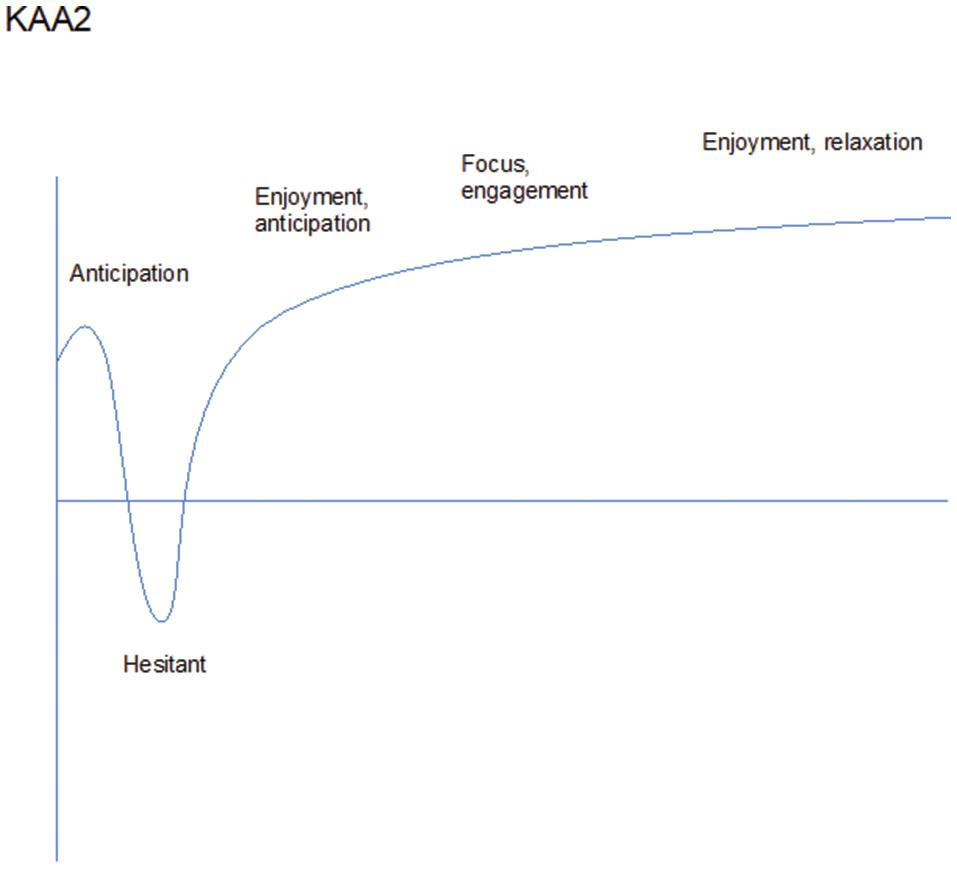

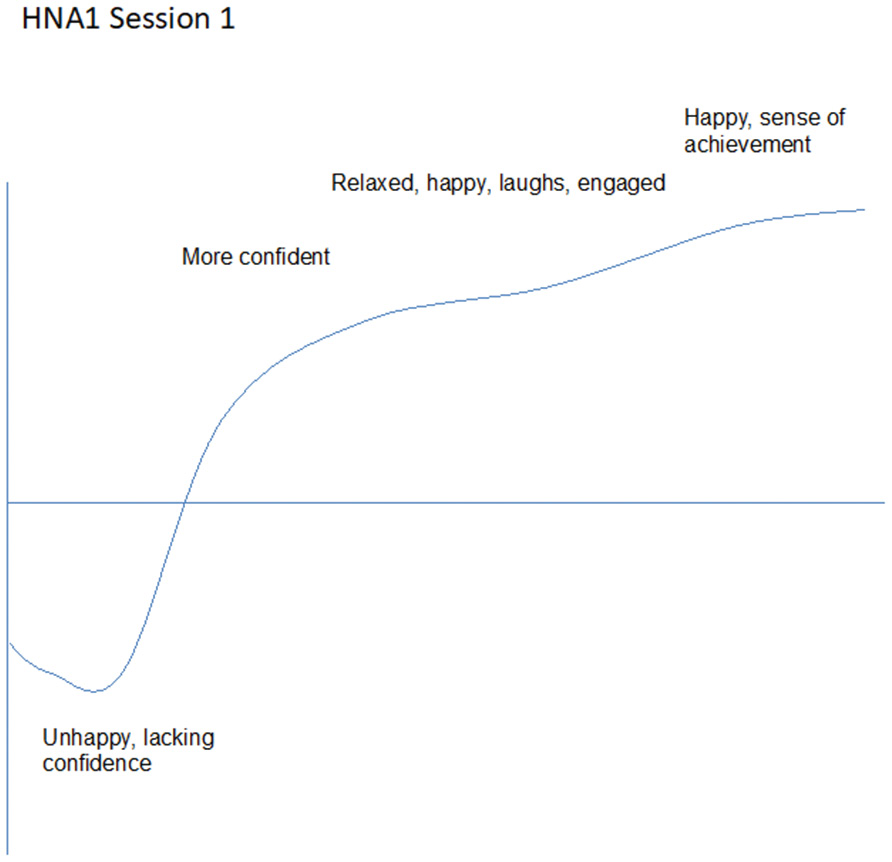

Talk aloud graphs were used to plot durations and intensities of the artmaking journeying throughout the interventions. Figures 6 (KAA2) and 7 (HANA1) demonstrate the shifts in emotions throughout an artmaking session; they represent an average graph across ×4 sessions. Both are artists, KAA2 having autoimmune illness and HANA1 no autoimmune illness. Both demonstrated that there is considerable emotional journeying throughout an artmaking session. There was a general trend across time to happiness and sense of achievement when making art over time.

FIGURE 6 | Talk aloud summary graph (KAA2).

FIGURE 7 | Talk aloud summary graph (HANA1).

The graphs show that there has been significant engagement with emotional cognition, whether positively or negatively, when making art. It shifted from frustration, disappointment, to satisfaction through persistence. Participants generally identified with one another that using visual narratives and working with embodied material processes supported their personal sense of being, toward positive emotional outcomes and general wellbeing. This was often described as “feeling good” during and after working at home or when finishing a workshop. Many participants spoke of the capacity to “lose time” during the workshops or at home, indicating that many were able to reach some level of flow state (Csikszentmihalyi et al., 2014) when making art.

Making Art as an Ethico-onto-epistemology

Studio art learning spaces accept diversity and have the capacity to support empathic knowing and empathic journeying. Barad (2007) speaks of an ethico-onto-epistemology that she later describes as a relational reworked model of ethical mattering of the world (Barad, 2012, p. 208). Clifton and Grushka (2022) have identified that a studio art learning ecology employing artful empathic approaches is a performative and space where the assemblage of meanings and possibilities can shift and emerge between and within participants. Artful methods produce empathic knowing and include arts-based inquiry, art as research, and visual narrative methods. The methods and the generated knowledge emerge from experience, observation, and the intuiting and feeling body. It is an ecology with interrelational elements and authentic forums offering open and social spaces, places of tolerance. Art therapy also speaks to the ideas of place-informed practice, where shared experiences can nurture social, material, and discursive opportunities as sites of folding and becoming (Fenner, 2017).

Deleuze (1990) describes the creation of our own ethical sense of being and knowing as “truth is producing existence” (p. 134). Furthermore more for Deleuze “sense is expression, it is the perceived, the remembered, the imagined” (2004, p. 110). It resides in an individual’s beliefs or desires and surfaces in their intuiting acts, such as artmaking. It is activated by the self and the world of contingencies significantly shaped by events, memory, and “other” narratives. Artmaking is a form of truth production, as the workshop facilitator states: “my practice is me.” How we fold our assemblage of narratives is an embodied, remembered, and recalled universe of events, folded and all are dependent on related affective intensities. The retelling of narratives allows the imagination to reconfigure the narratives through a shared retelling. It might be described as a collaborative mode of art therapy (Betts & Huet, 2023).

The most significant findings demonstrate how artmaking narratives link time and memory toward adaptability and resilience in the participants. The data evidence showed that time and memory work, explored through inquiry/resilience visual narratives, supported a renewed confidence in the life journeys of the participants. One immediate benefit for healing was a “forgetting about their illness” and “the temporary absence of pain,” plus the capacity to “lose time” during the workshops or when making art at home. This indicates that they were significantly occupied at a cognitive and emotional level that was described by some as “experiencing a kind of meditative state” that energized them.

Discussion: Crossing Borders Art, Education, Health, and Therapy

Studio art therapy is grounded in an understanding that the human mind evolved to work in an emotional relationship with others (Dissanayake, 2009). The mind receives our sensory world of feelings and perceptions and triggers our affective responses in complex and relational ways as we reason (Damasio, 2021). Being and making art are subjectivity felt, internalized, imagined, and imaged. This embodied process is always constructed from the uniqueness of our personal experiences and performatively shapes our identities and unique points of view about the world (Deleuze, 2006).

Ecologies describe how subjectivities or identities relationally evolve within complex living and adapting social systems. For Guattari (1995), the environmental, social, and mental ecologies move us beyond any consideration of binary constructs such as doctor, therapist, or patient. A Deleuzoguattarian ecology embeds the concept of autopoiesis (Thompson, 2004) and is understood as living and adapting within the wider world of sense making and experience. Becoming is a condition of all life and is constituted within a living machine where many domains of interaction operate as both circular and within a self-referentially organized ecology (Thompson, 2004). For Deleuze and Guattari (1987), doing, thinking, and one’s entire being can be described as a piecing together and a generating of multiple identities; these can be seen as shifting and fluid assemblages. Identifying spaces and places of complex ecologies in which human action, interaction, and intelligence are involved has come to be known as a new ecological paradigm, a general ecology (Horl, 2017) of which the studio art therapy learning ecology operates.

When these ecology assemblages interact in a social field, they are filled with conflicts and contradictions (Bennett, 2010; Fuglsang & Sorensen, 2016). Identities are complex and are impacted by personal desires, intensities of feelings, life experiences, and the constant need to navigate personal events, adapt, and survive. Our bureaucratic organizations, such as health systems and schools, contain and seek to control in terms of specific structurally identified outcomes. Being well or feeling well maybe driven more by a desire to escape these controls, or defining labels, and take on new lines of flight, flows, or find fluid or rhizomic ways to navigate our future becoming (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987; Masny, 2016). Art studio therapy, as a learning ecology offers imaginative adaptive opportunities. In this context, art studio learning supports therapeutic imminence with transformative and performative power through making art. Studio art therapy supports the exploration of life’s relational components within the general ecology and can both influence and can be troubled (Haraway, 2016). The art therapy learning ecology is also a space that will allow the troubling to be examined and retold. It is the qualities of these learning spaces that attracted both KAA1 and KAA2.

Remaking one’s personal life, adapting within complex structural systems, requires finding ways to develop the skills of self-awareness for wellbeing. This increasingly brings into play the relationships between art, education, health, and therapy and the discourse that links creative arts therapies and arts health (Betts and Huet, 2023). The arts have always provided an expressive and aesthetic way for the individual and community to explore the human experience through an array of different cultural production forms (Dissanayake, 2001, 2009, 2014). Wellbeing outcomes, across a range of healthcare settings, improve when the focus shifts to the quality of human experiences. Feeling the insight (Shen et al., 2018) through visual narrative work requires time—time to explore the symbolic and material experiences of artmaking, time to explore one’s personal narratives across spaces and places, time to encounter one’s affective being, time to reflect on the self, time to reimagine one’s identities, and time to accept the struggle of the journey. The studio art space also allows one to share their journeying with others, and relationally ease the burden. All the participants (artists and non-artists) in this study used personal narratives as a form of visual autoethnographic inquiry. All participants were encouraged to engage with and through intuitive material actions. Drawing new images, attaching words that carry meaning, or indeed simply applied and retrospective descriptive storying to support the images they produced. Because they are personal, they do not carry the anxieties that making art can have in terms of being successful at communicating a message, concept, or idea to a wider public. Self-reflective learning or “looking back” on the emergence of their creative product had both subjective and objective benefit. Visual narratives perform the role of being personal props or private recording spaces in support of self-reflection, the generation of ideas and new associations. The participants invented personal symbolic images that worked as personal signs or signposts, or they attached more private metaphoric meanings to their images. All participants were encouraged to juxtapose real images and their invented symbols and metaphors. The works created within the diaries can indeed be works of art, often created with as much aesthetic sensitivity as the artwork, in the examples of KAA1’s artworks. The participants working with art diaries demonstrated the diaries’ benefit to them as they were used as “thinking with, storytelling” (Haraway, 2016). For all participants it mattered to them that they were able to work through artmaking in developing an understanding of their illness life storying. It mattered what stories they chose to tell. Most sought to cross over from illness narratives to stories of resilience and strength (Grushka & Bellette, 2016). They yearned for a wellness world away from their existing past histories; they yearned to cross over into another world.

The diaries of all participants were foregrounded by strong affective responses to memories of past and present events to begin a new storytelling. In the case of many, this threw up sociocultural or ethical conflicts or tensions. In the participants selected for this article, their personal worlds were characterized by points of disruption such as identity struggles, loss, childhood legacies, broken families, personal or family illness, and responsibility to others. Symbols such as the paper-doll were selected and then linked with their enduring wellbeing explorations as they attempted to communicate physical pain, challenges, frustration, exhaustion, and disappointment—in particular, the disappointment to families and children. Participants also spoke of sustaining focus and deep engagement when doing memory work and making art. They were always surprised at the loss of time during artmaking sessions. For the autoimmune participants, it was a temporary alleviation of illness symptoms, a forgetting of both time and pain even if for a short time. An autoimmune participant described this as “I tend to get lost in what I’m doing, which is really good and I find that I’m sleeping better.” The diaries spoke to the borders between being daughters, mothers, wives, friends, patients, and being ill or well.

The research sought to find direct links to the broader sociocultural constructs of being trapped within and across borders, such as illness and wellness, patient, or victim. The assemblages produced were about crossing between roles and links to family, friends, and society from a personal perspective. Those that embarked on the project self-selected because they had a genuine longing for wellness over illness. No direct symbolic works connected to medical institutions in a critical socio-critical construct. Evidence did demonstrate that this was a troubling space, surrounded by our “institutions” and illnesses. It demonstrated their complex illness assemblages and how they were unable to easily tell this story. The findings demonstrate the deeply felt, material and expressive work that is unlocked when making art. Indeed, there were strong links between Fenner’s (2017) description of an art therapy workshop that carried intense sensory, affective, and meaning-filled site or placeworlds wherein social, material, discursive, and psychological forces mingle (p. 1). Both studio art therapy spaces and Fenner’s art therapy space are described in Deleuzoguattarian terms as spaces where multiple forces including political, ephemeral, and critical forces are at play.

This article can speak to some of the borderlines that confronted the participants’ multiple life assemblages from the qualitative experiential perspective. This perspective appears to be one that can carry transformational potential for the participants. It demonstrates that contemporary health constructs are currently marked by borderlines, such as illness and wellness or community and family, and how the AVNAW project attempts to trouble these borderlines or cut through and find new ways or lines of flight where visual narratives of resilience emerge. Both education and health within the socioeconomic narrative have shifted to accountable and quantifiable measurements of learning and healing that continue to trouble the individuals. They are tired, tired of going to doctors, being sick, having pain. The studio art therapy learning ecologies were active spaces made up of bodies, actions, and passions where the artmaking cut through the narrative borders that surround people living with autoimmune illness. They were able to encounter the trouble at the borderlines, “de-territorise” them, carry them away, or “re-territorise” them (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987, p. 88). Finding methods to develop these self-reflective and creative skills for rhizomic potential (Masny, 2016) can support one’s capacity to manage stress, adapt and change.

The findings revealed in this article demonstrate that the studio art therapy spaces that work with visual narratives and the materiality of artmaking generate personal imaginative, performative, and reflective capacities able to affect shifts in emotional and physical wellbeing for an individual over time. The artists’ metaphoric and symbolic borderlines, explored within artmaking and the visual diaries, are personal sense-making tools. They allow imaged intensities and multidimensional actions to combine as enablers of adaptive and creative reasoning via a performative project (Rose et al., 2021). The studio art learning ecology also allows the artist to participate with others and find ways to manipulate illness and wellness narratives that continuously disrupt and re/de-assemble narratives to reveal the “other.” Visual narratives can fold time and memory; they can bring forth new possible resilience and wellness narratives.

Conclusion: Body, Meaning, and Healing

The studio art therapy ecology can encourage participants to challenge the dominant or well-worn journeying of themselves and others. The AVNAW project was originally conceived to support people living with autoimmune illness and was seen as a wellbeing strategy and resource responding to a need identified by health professionals. It sought to find ways to improve health measures beyond established medical interventions. The structural connections and differentiations are fluid if one applies a Deleuzoguattarian philosophy to the liminal potential that lies at the borderlands between visual arts therapies and art studio practice operating across both education and health. Deleuzoguattarian philosophy in this article also offers a language to extend current thinking about the way artists and artists with autoimmune illness use their intuiting capacities to create future possibilities.

Care, community, belonging, and resilience are core to a studio art therapy learning environment. Both art therapy and studio art therapy bring forth generative spaces operating between self and other. The underlying philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari (1987) sees desire as a force of positivity, a force toward imaginative and adaptive being as a de-territorizing act, not the interiorizing of an identity illness as defined, constructed, and labeled by society. The project called Art, Visual Narrative, and Wellbeing (AVNAW) and the voices of its participants speak to a people to come, through focusing on the affective and the expressive spaces that emerge in the artmaking production of visual narratives. It further explores the voices of the participants as actors in their own ethico-onto-epistemological world (Barad, 2007), a world where the body, meaning, and healing are nurtured to build resilience for better health outcomes.

The borderlines between the arts and health do not simply apply to the arts, health, and medical transdisciplinary narratives that surround the AVNAW project for people with autoimmune illness. They apply to how we all live with, within, or straddle our contemporary health constructs marked by illness and wellness, health systems, community, and family. The AVNAW project was made up of bodies, actions, and passions and the creative energies of the participants who engaged in border crossing between sociocultural and personal questioning. Both art therapy and studio art therapy speak to people, places, times, flows, and intuitive energies and work with material, symbolic, and conceptual shifts. Both have the potential to dwell in liminal spaces and offer collective ways toward becoming as a wellness narrative. The practice-based spaces at the borders between art therapy and arts health, such as studio art therapy, speak to this becoming and embed art, education, health, and therapy.

About the Author

Kathryn Grushka’s research crosses Arts Health, art curriculum, art/science, arts-education, e-learning, visual learning, and the Creative Industries. She has national and international research experience. Her research draws on empirical and philosophical fields in narrative, arts-based methods, health measurement, and the performative work of image in representing the contemporary subject. Kathryn publishes nationally and internationally. She works with a range of research and editorial teams and organisations. From 2024–2026: South-East Asian Pacific World Congress representative, International Society Education through Art (InSEA) and IJETA Review Editor; and International Association for Creative Arts in Education and Therapy (IACAET), 2024–2025: Co-chair Research Committee IACAET. Kathryn is a practicing artist with a national reputation.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-mail: Kath.grushka@gmail.com. ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4228-3606.

Curriculum Vitae

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kathryn-Grushka

References

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

Barad, K. (2012). On touching—The inhuman that therefore I am. Differences, 23(3), 206–223.

Barone, T., & Eisner, E. W. (2012). Arts-based research. Sage.

Barraclough, S. (2018). Ethico-onto-epistemological becoming. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 15, 375–380. DOI: 10.1080/14780887.2018.1430732.

Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Duke University Press.

Betts, D., & Huet, V. (2023). Bridging the creative arts therapies and arts in health. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Clifton, S., & Grushka, K. (2022). Rendering artful and empathic arts-based performance as action. LEARNing Landscapes, 15, 89–107.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., Abuhamdeh, S., & Nakamura, J. (2014). Flow and the foundations of positive psychology: The collected works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Springer.

Damasio, A. (2021). Feeling and knowing: Making minds conscious. Pantheon Books, Penguin Random House.

DeLanda, M. (2022). Assemblages as solutions to problems. In: Assemblage theory (pp. 165–188). Edinburgh University Press.

Deleuze, G. (1990). Negotiations, Joughin, M., Trans. Columbia University Press.

Deleuze, G. (1993). The fold: Leibniz and the Baroque. Continuum.

Deleuze, G. (2004). The logic of sense. Continuum.

Deleuze, G. (2006). The fold: Leibniz and the Baroque, Conley, T., Trans. University of Minnesota Press.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. Athlone Press.

dell’Agnese, E., & Szary, A. L. (2015). Borderscapes: From border landscapes to border aesthetics. Geopolitics, 20, 4–13. DOI: 10.1080/14650045.2015.1014284.

Denzin, N. (2018). Performance autoethnography: Critical pedagogy and the politics of culture (2nd ed.). Routledge. DOI: 10.4324/9781315159270.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). The sage handbook of qualitative research, 3rd edition. Sage.

Dissanayake, E. (2001). Homo aestheticus: Where art comes from and why. University of Washington Press.

Dissanayake, E. (2009). The artification hypothesis and its relevance to cognitive science. Evolutionary Aesthetics and Neuroaesthetics, 5, 148–173. DOI: 10.1515/cogsem.2009.5.fall2009.136.

Dissanayake, E. (2014). A bon fide ethology view of art: The artification hypothesis. In: C. Sütterlin, W. Schiefenhövel, C. Lehmann, J. Forster, & G. Apfelauer (Eds.), Art as behaviour: An ethological approach to visual and verbal art, music and architecture (Vol. 10, pp. 43–62). Hanse Studies, BIS-Verlag der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg.

Fenner, P. (2017). Art therapy places, flows, forces, matter and becoming. In: International Art Therapy Conference Proceedings. Art Therapy Online, 8. https://journals.gold.ac.uk/index.php/atol/article/view/421.

Finley, S. (2008). Arts-based research. In: G. Knowles & A. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples and issues (pp. 72–83). Sage.

Fuglsang, M., & Meier Sorensen, B. (2016). Deleuze and the social. Edinburgh University Press.

Giudice, C., & Giubilaro, C. (2015). Re-imagining the border: Border art as a space of critical imagination and creative resistance. Geopolitics, 20, 79–94. DOI: 10.1080/14650045.2014.896791.

Grebosz-Harin, K., Thun-Hohenstei, L., Schuchter-Wiegand, A. K., Iron, Y., Bathke, A., Phillips, K., & Clift, S. (2022). The need for robust critique of arts and health research: Young people, art therapy and mental health. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 821093. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.821093.

Grushka, K. (2005). Artist as reflective self-learners and cultural communicators: An exploration of the qualitative aesthetic dimension of knowing self through reflective artmaking. Reflective Practice, 6, 353–366.

Grushka, K. (2010). Conceptualising visual learning as an embodied and performative pedagogy for all classrooms. Encounters in Theory and History of Education, 11. DOI: 10.24908/eoe-ese-rse.v11i0.3167.

Grushka, K., & Bellette, A. (2016). Interactive reflection in a photomedia participatory e-feed learning culture. In C. Coleman & A. Flood (Eds.), Enabling reflective thinking, reflective practices in learning and teaching (pp. 211–233). Common Ground.

Grushka, K., Squance, M. L., & Reeves, G. (2014). Visual narratives performing and transforming people with autoimmune illness. A pilot case study. Journal of Applied Arts and Health, 5, 7–24. DOI: 10.1386/jaah.5.1.7_1.

Grushka, K., van Gestel, M., & Skates, C. (2019). Crafting identities: Folding and stitching the self. Art/Research International, 4, 287–311.

Grushka, K., Lawry, M., Chand, A., & Devine, A. (2022). Visual borderlands: Visuality, performance, fluidity and art-science learning. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 54, 404–431. DOI: 10.1080/00131857.2020.1859368.

Guattari, F. (1989). Guattari the three ecologies. Coninuum.

Guattari, F. (1995). Chaosmosis: An ethico-aesthetic paradigm. Power Publications.

Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Hetland, L., Winner, E., Veenema, S., & Sheridan, K. (2014). Studio thinking 2. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Horl, E. (2017). General ecology: The new paradigm. Bloomsbury Academic.

Ilchmann-Diounou, H., & Menard, S. (2020). Psychological stress, intestinal barrier dysfunctions, and autoimmune disorders: An overview. Frontiers in Immunology, Mucosal, 11, 1823. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01823.

Kearns, R. (1997). Narrative and metaphor in health geographies. Progress in Human Geographies, 21, 269–277. DOI: 10.1191/030913297672099067.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press.

Levine, S. K. (2022). Ecopoiesis during the global crisis. Ecopoiesis: Eco-Human Theory and Practice, 3, 3–4.

Majid, U., & Kandasamy, S. (2021). The rationales for and challenges with employing art-based health services research (ABHSR): A qualitative systematic review of primary studies. Medical Humanities, 47, 266–273. DOI: 10.1136/medhum-2020-011845.

Masny, D. (2016). Problematizing qualitative research: Reading a data assemblage with rhizoanalysis. Qualitative Inquiry, 22, 666–675. DOI: 10.1177/1532708616636744.

McQuillan, M. (2000). The narrative reader. Routledge.

Morujao, C., & Leite, A. M. T. (2023). Somatization and embodiment. Philosophical Psychology, 1–28. DOI: 10.1080/09515089.2023.2241498.

Rose, E., Bingley, A., & Rioseco, M. (2021). Art of transition: A Deleuzoguattarian framework. Action Research, 20, 380–405. DOI: 10.1177/1476750320960817.

Semetsky, I. (2010). The folds of experience, or: Constructing the pedagogy of values. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 42, 476–488. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-5812.2008.00486.x.

Shen, W., Tong, Y., Yuan, Y., Zhan, H., Liu, C., Luo, J., & Cai, H. (2018). Feeling the insight: Uncovering somatic markers of the “aha” experience. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 43, 13–21. DOI: 10.1007/s10484-017-9381-1.

Thompson, E. (2004). Life and mind: From autopoiesis to neurophenomenology. A tribute to Francisco Varela. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 3, 381–398. DOI: 10.1023/B:PHEN.0000048936.73339.dd.

Tokolahi, E. (2010). Case study: Development of a drawing-based journal to facilitate reflective practice. Reflective Practice, 11, 157–170. DOI: 10.1080/14623941003665976.

Voukelatou, V., Gabrielli, L., Miliou, I., Cresci, S., Sharma, R., Tesconi, M., & Pappalardo, L. (2021). Measuring objective and subjective well-being: Dimensions and data sources. International Journal of Data Science and Analysis, 11, 279–309. DOI: 10.1007/s41060-020-00224-2.

a This paper is a pre-published version of Studio Art Therapy Learning Ecology: Crossing Borders between Art, Education, Health, and Therapy.