This simple single-case study aimed to illustrate a new way of working. Considering Kazdin’s six criteria, the design satisfied all criteria except experimental manipulation and consistency between studies. Therefore, a subsequent step to our single case is to replicate the study in an RCT with the same structure, comparing the change of the two constructs over time in the experimental group with the control group. Finally, we know that music therapy is complex, and there is not only one change process and one change mechanism. Therefore, researchers can add every change process and mechanism to create the most exhaustive and parsimonious model that responds to research questions.

Change is a unique and multifaceted phenomenon of music therapy, and a single article cannot fully explain it. However, this introductory overview with a proposed model and example aimed to introduce and explore the various aspects of change, how to study it, what we know, what we do not know, and what we need to know about it. New studies about the efficacy of music therapy have been made in recent years, but it only tells a limited part of the overall story. The existing literature is extremely limited about predictors, moderators, shapes of change, stages of change, processes, and mechanisms in music therapy research. Further studies are needed for every aspect of change, and replication studies should be conducted to ensure that results are not biased.

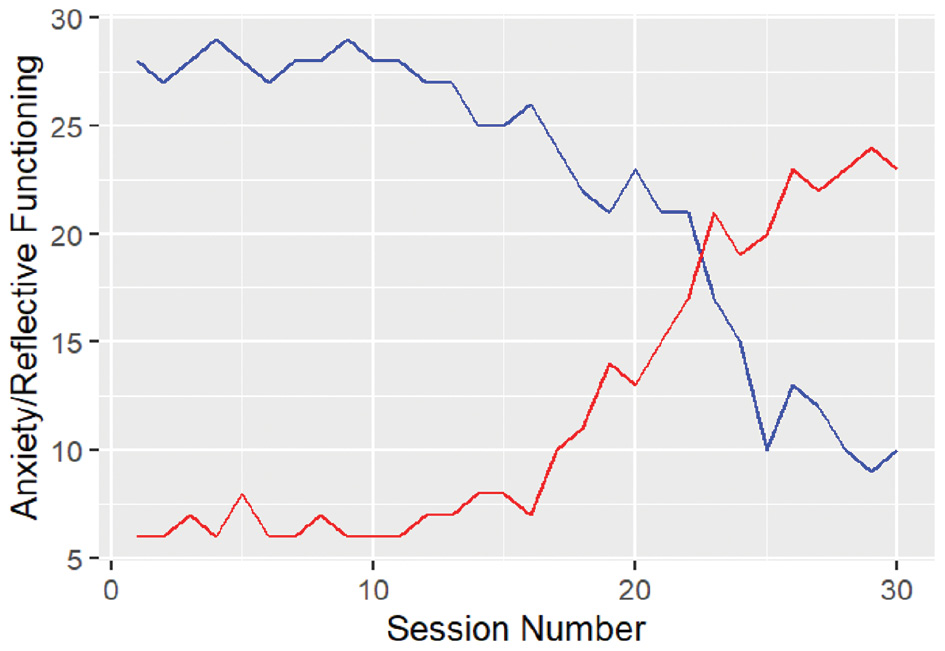

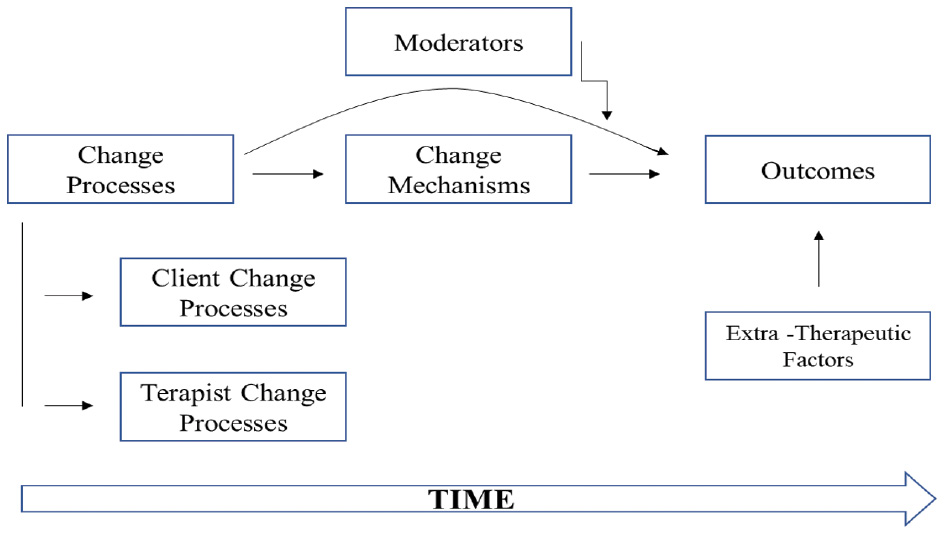

Moreover, multiple change aspects in music therapy are an exciting means of investigation because, when carried out simultaneously, links can be created between the change’s study areas: if, when, how, and why (see Figure 2). For example, by investigating whether musical synchronicity mediates or moderates (or both) within the well-researched therapeutic relationship within music therapy improvisation contexts, powerful findings may be gleaned. Dynamic systems theory (DST) could be used to model music therapy change processes as elements of a complex system that evolves over time. DST would allow for more aspects of change and more variables to be considered simultaneously, reflecting the complexity of the therapy (for an application of DST to music therapy, see [masked authors]).

Music therapy research would benefit from building on the existing knowledge as well as following the advice of Hillecke et al. (2005) to adopt a pluralistic approach, integrating the methodologies of natural sciences (e.g., biology, medicine), mathematics (e.g., statistics, physics), arts (e.g., music, musicology), behavioral and social sciences (e.g., psychotherapy, psychology, sociology). Indeed, since music therapy uses music to treat individuals in clinical contexts, methodologies (e.g., data collection, assessment, design) to evaluate intervention or to understand how a treatment works can be imported from psychotherapy, biology, or medicine. Statistics can offer more sophisticated models to capture change and its processes. Physics can teach us to insert time in the statistic models to represent the evolution of change over time. All of these contribute toward a further understanding of what moderates and mediates change in exciting new complex ways of design such as mixed methods. In conclusion, only complex methods can model complex phenomena.

Lorenzo Antichi is a psychologist affiliated with the University of Florence, Italy. He is the author of publications concerning theoretical and methodological aspects of Clinical Psychology, Psychotherapy, and Music Therapy, especially the change processes, idiographic methods, and longitudinal analysis.

Rebecca Zarate is the Associate Dean for Research in the College of Fine Arts and Director of the Arts & Health Innovation Lab at the University of Utah. She is the author of Music Psychotherapy and Anxiety in Social, Community, and Clinical Contexts. Dr. Zarate publishes and presents on topics related to trauma, anxiety, stress response systems, and musical/creative processes in clinical improvisation CAT contexts. E-mail:rebecca.zarate@utah.edu. ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1755-3990, Website: https://artsandhealth.utah.edu/.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Aalbers, S., Fusar-Poli, L., Freeman, R. E., Spreen, M., Ket, J. C. F., Vink, A. C., Maratos, A., Crawford, M., Chen, X. J., & Gold, C. (2017). Music therapy for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2017(11), CD004517. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004517.pub3.

Aigen, K. (1991). The roots of music therapy: Towards an indigenous research paradigm (Doctoral dissertation, New York University, 1990). Dissertation Abstracts International, 52(6), 1933A.

Alexander, L. A., McKnight, P. E., Disabato, D. J., & Kashdan, T. B. (2017). When and how to use multiple informants to improve clinical assessments. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 39(4), 669–679. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10862-017-9607-9.

Baker, F. A., Rickard, N., Tamplin, J., & Roddy, C. (2015). Flow and meaningfulness as mechanisms of change in self-concept and well-being following a songwriting intervention for people in the early phase of neurorehabilitation. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9, 299. https://doi.org/10.3389/FNHUM.2015.00299.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research. Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173.

Barry, P., O’Callaghan, C., Wheeler, G., & Grocke, D. (2010). Music therapy CD creation for initial pediatric radiation therapy: A mixed methods analysis. Journal of Music Therapy, 47(3), 233–263. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/47.3.233.

Bibb, L., & McFerran, K. S. (2018). Musical recovery: The role of group singing in regaining healthy relationships with music to promote mental health recovery. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 27(3), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2018.1432676.

Bradt, J. (2021). Where are the mixed methods research studies? Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 30(4), 311–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2021.1936771.

Bradt, J., Burns, D. S., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Mixed methods research in music therapy research. Journal of Music Therapy, 50(2), 123–148. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/50.2.123.

Burns, D. S., Meadows, A. N., Althouse, S., Perkins, S. M., & Cripe, L. D. (2018). Differences between supportive music and imagery and music listening during outpatient chemotherapy and potential moderators of treatment effects. Journal of Music Therapy, 55(1), 83–108. https://doi.org/10.1093/JMT/THY001.

Chang, Y. S., Chu, H., Yang, C. Y., Tsai, J. C., Chung, M. H., Liao, Y. M., Chi, M. J., Liu, M. F., & Chou, K. R. (2015). The efficacy of music therapy for people with dementia: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(23–24), 3425–3440. https://doi.org/10.1111/JOCN.12976.

de Witte, M., Spruit, A., van Hooren, S., Moonen, X., & Stams, G. J. (2020). Effects of music interventions on stress-related outcomes: A systematic review and two meta-analyses. Health Psychology Review, 14(2), 294–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2019.1627897.

de Witte, M., Orkibi, H., Zarate, R., Karkou, V., Sajnani, N., Malhotra, B., Ho, R. T. H., Kaimal, G., Baker, F. A., & Koch, S. C. (2021). From therapeutic factors to mechanisms of change in the creative arts therapies: A scoping review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 2525. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.678397.

Doss, B. D. (2004). Changing the way we study change in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(4), 368–386. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy/bph094.

Falkenström, F., Solomonov, N., & Rubel, J. (2020). Using time-lagged panel data analysis to study mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research: Methodological recommendations. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 20(3), 435–441. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12293.

Feng, F., Zhang, Y., Hou, J., Cai, J., Jiang, Q., Li, X., Zhao, Q., & Li, B. A. (2018). Can music improve sleep quality in adults with primary insomnia? A systematic review and network meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 77, 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.10.011.

Ghetti, C. M. (2012). Music therapy as procedural support for invasive medical procedures: Toward the development of music therapy theory. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 21(1), 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2011.571278.

Gold, C., Wigram, T., & Voracek, M. (2007). Predictors of change in music therapy with children and adolescents: The role of therapeutic techniques. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 80(4), 577–589. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608307X204396.

Gold, C., Solli, H. P., Krüger, V., & Lie, S. A. (2009). Dose–response relationship in music therapy for people with serious mental disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(3), 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.001.

Haslbeck, F. B. (2014). Creative music therapy with premature infants: An analysis of video footage†. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 23(1), 5–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2013.780091.

Hayes, A. M., Laurenceau, J. P., Feldman, G., Strauss, J. L., & Cardaciotto, L. A. (2007). Change is not always linear: The study of nonlinear and discontinuous patterns of change in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(6), 715–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.008.

Hermans, H. J. M. (1988). On the integration of nomothetic and idiographic research methods in the study of personal meaning. Journal of Personality, 56(4), 785–812. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1467-6494.1988.TB00477.X.

Hillecke, T., Nickel, A., & Bolay, H. V. (2005). Scientific perspectives on music therapy. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1060(1), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1196/ANNALS.1360.020.

Hilsenroths, M. J., Ackerman, S. J., & Blagys, M. D. (2010). Evaluating the phase model of change during short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 11(1), 29–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/713663851.

Hohmann, L., Bradt, J., Stegemann, T., & Koelsch, S. (2017). Effects of music therapy and music-based interventions in the treatment of substance use disorders: A systematic review. PLoS One, 12(11), e0187363. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187363.

Howard, K. I., Mark, S., Merton, K., Krause, S., & Orlinsky, D. E. (1986). The dose-effect relationship in psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 41(2), 159–164. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.2.159.

Howard, K. I., Moras, K., Brill, P. L., Martinovich, Z., & Lutz, W. (1996). Evaluation of psychotherapy: Efficacy, effectiveness, and patient progress. American Psychologist, 51(10), 1059–1064. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.51.10.1059.

Islam, S. R., & Ferdousi, S. (2019). Music therapy on non linear assessment of cardiac autonomic function in patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of Bangladesh Society of Physiologist, 14(1), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.3329/jbsp.v14i1.41995.

Jacobson, N. S., Follette, W. C., & Revenstorf, D. (1984). Psychotherapy outcome research: Methods for reporting variability and evaluating clinical significance. Behavior Therapy, 15(4), 336–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(84)80002-7.

Jia, R., Liang, D., Yu, J., Lu, G., Wang, Z., Wu, Z., Huang, H., & Chen, C. (2020). The effectiveness of adjunct music therapy for patients with schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113464.

Kazdin, A. E. (2007). Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432.

Kazdin, A. E. (2009). Understanding how and why psychotherapy leads to change. Psychotherapy Research, 19(4–5), 418–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300802448899.

Kellett, S., Hall, J., & Dickinson, S. C. (2019). Group cognitive analytic music therapy: A quasi-experimental feasibility study conducted in a high secure hospital. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 28(3), 224–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2018.1529697.

Kerlinger, F. N. (1973). Foundations of behavioral research. Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Kim, W. (2012). Music therapists’ job satisfaction, collective self-esteem, and burnout. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 39(1), 66–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2011.10.002.

Koch, S. C. (2017). Arts and health: Active factors in arts therapies and a theory framework of embodied aesthetics. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 54, 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.02.002.

Koch, S. C., Riege, R. F. F., Tisborn, K., Biondo, J., Martin, L., and Beelmann, A. (2019). Effects of dance movement therapy and dance on health-related psychological outcomes. A meta-analysis update. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1806. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01806.

Koffmann, A. (2018). Has growth mixture modeling improved our understanding of how early change predicts psychotherapy outcome? Psychotherapy Research, 28(6), 829–841. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1294771.

Kraemer, H. C., Wilson, G. T., Fairburn, C. G., & Agras, W. S. (2002). Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(10), 877–883. https://doi.org/10.1001/ARCHPSYC.59.10.877.

Krebs, P., Norcross, J. C., Nicholson, J. M., & Prochaska, J. O. (2018). Stages of change and psychotherapy outcomes: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1964–1979. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22683.

Laurenceau, J. P., Hayes, A. M., & Feldman, G. C. (2007). Some methodological and statistical issues in the study of change processes in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(6), 682–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.007.

Leubner, D., & Hinterberger, T. (2017). Reviewing the effectiveness of music interventions in treating depression. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1109. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01109.

Lindenfelser, K. J., Hense, C., & Mcferran, K. (2011). Music therapy in pediatric palliative care: Family-centered care to enhance quality of life. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 29(3), 219–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909111429327.

Loewy, J., Stewart, K., Dassler, A. M., Telsey, A., & Homel, P. (2013). The effects of music therapy on vital signs, feeding, and sleep in premature infants. Pediatrics, 131(5), 902–918. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1367.

Lu, G., Jia, R., Liang, D., Yu, J., Wu, Z., & Chen, C. (2021). Effects of music therapy on anxiety: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychiatry Research, 304, 114137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114137.

Lutz, W., de Jong, K., Rubel, J. A., & Delgadillo, J. (2021). Measuring, predicting, and tracking change in psychotherapy. In M. Barkham, W. Lutz, & L. G. Castonguay (Eds.). Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change (7th ed., pp. 89–133). Wiley.

McDermott, O., Crellin, N., Ridder, H. M., and Orrell, M. (2013). Music therapy in dementia: A narrative synthesis systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(8), 781–794. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.3895.

Molenaar, P. C. M. (2009). A manifesto on psychology as idiographic science: Bringing the person back into scientific psychology, this time forever. Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research and Perspectives, 2(4), 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15366359mea0204_1.

Molenaar, P. C. M., & Campbell, C. G. (2009). The new person-specific paradigm in psychology. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(2), 112–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1467-8721.2009.01619.X.

Mössler, K., Chen, X., Heldal, T. O., & Gold, C. (2011). Music therapy for people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-like disorders. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd004025.pub3.

Mössler, K., Assmus, J., Heldal, T. O., Fuchs, K., & Gold, C. (2012). Music therapy techniques as predictors of change in mental health care. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 39(4), 333–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AIP.2012.05.002.

Mössler, K., Gold, C., Aßmus, J., Schumacher, K., Calvet, C., Reimer, S., Iversen, G., & Schmid, W. (2019). The therapeutic relationship as predictor of change in music therapy with young children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(7), 2795–2809. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3306-y.

Mössler, K., Schmid, W., Aßmus, J., Fusar-Poli, L., & Gold, C. (2020). Attunement in music therapy for young children with autism: Revisiting qualities of relationship as mechanisms of change. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(11), 3921–3934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04448-w.

Mulder, J. D., & Hamaker, E. L. (2020). Three extensions of the random intercept cross-lagged panel model. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 28(4), 638–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2020.1784738.

Norcross, J. C., Krebs, P. M., & Prochaska, J. O. (2011). Stages of change. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(2), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/JCLP.20758.

Orkibi, H. (2021). Creative adaptability: Conceptual framework, measurement, and outcomes in times of crisis. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 588172. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.588172.

Orkibi, H., Azoulay, B., Regev, D., and Snir, S. (2017). Adolescents’ dramatic engagement predicts their in-session productive behaviors: A psychodrama change process study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 55, 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.04.001.

Owen, J., Adelson, J., Budge, S., Wampold, B., Kopta, M., Minami, T., & Miller, S. (2015). Trajectories of change in psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(9), 817–827. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22191.

Pasiali, V. (2012). Supporting parent-child interactions: Music therapy as an intervention for promoting mutually responsive orientation. Journal of Music Therapy, 49(3), 303–334. https://doi.org/10.1093/JMT/49.3.303.

Porter, S., McConnell, T., Clarke, M., Kirkwood, J., Hughes, N., Graham-Wisener, L., Regan, J., McKeown, M., McGrillen, K., & Reid, J. (2017). A critical realist evaluation of a music therapy intervention in palliative care. BMC Palliative Care, 16(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12904-017-0253-5.

Potvin, N., Bradt, J., & Ghetti, C. (2018). A theoretical model of resource-oriented music therapy with informal hospice caregivers during pre-bereavement. Journal of Music Therapy, 55(1), 27–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/thx019.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701341316.

Prochaska, J. O., & Diclemente, C. C. (1986). Toward a comprehensive model of change. In W. R. Miller & N. Heather (Eds.), Treating addictive behaviors (pp. 3–27). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-2191-0_1.

Ribeiro, M. K. A., Alcântara-Silva, T. R. M., Oliveira, J. C. M., Paula, T. C., Dutra, J. B. R., Pedrino, G. R., Simões, K., Sousa, R. B., & Rebelo, A. C. S. (2018). Music therapy intervention in cardiac autonomic modulation, anxiety, and depression in mothers of preterms: Randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychology, 6(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-018-0271-y.

Rolvsjord, R., & Stige, B. (2015). Concepts of context in music therapy. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 24(1), 44–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2013.861502.

Salvatore, S., & Tschacher, W. (2012). Time dependency of psychotherapeutic exchanges: The contribution of the Theory of Dynamic Systems in analyzing process. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 253. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00253.

Schall, A., Haberstroh, J., & Pantel, J. (2015). Time series analysis of individual music therapy in dementia: Effects on communication behavior and emotional well-being. GeroPsych: The Journal of Gerontopsychology and Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(3), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1024/1662-9647/a000123.

Shiffman, S. (2009). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychological Assessment, 21(4), 486–497. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017074.

Silverman, M. J. (2011). Effects of music therapy on change readiness and craving in patients on a detoxification unit. Journal of Music Therapy, 48(4), 509–531. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/48.4.509.

Silverman, M. J., & Baker, F. A. (2018). Flow as a mechanism of change in music therapy: Applications to clinical practice. Approaches: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Music Therapy, 10(1), 43–51. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328268871.

Silverman, M. J., Baker, F. A., & MacDonald, R. A. R. (2016). Flow and meaningfulness as predictors of therapeutic outcome within songwriting interventions. Psychology of Music, 44(6), 1331–1345. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735615627505.

Song, M., Li, N., Zhang, X., Shang, Y., Yan, L., Chu, J., Sun, R., & Xu, Y. (2018). Music for reducing the anxiety and pain of patients undergoing a biopsy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74(5), 1016–1029. https://doi.org/10.1111/JAN.13509.

Standley, J. M. (2002). A meta-analysis of the efficacy of music therapy for premature infants. Journal of Pediatric Nursing: Nursing Care of Children and Families, 17(2), 107–113. https://doi.org/10.1053/JPDN.2002.124128.

Strauss, M. E., & Smith, G. T. (2009). Construct validity: Advances in theory and methodology. Annual Reviews, 5, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153639.

Stulz, N., & Lutz, W. (2007). Multidimensional patterns of change in outpatient psychotherapy: The phase model revisited. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63(9), 817–833. https://doi.org/10.1002/JCLP.20397.

Teckenberg-Jansson, P., Turunen, S., Pölkki, T., Lauri-Haikala, M. J., Lipsanen, J., Henelius, A., Aitokallio-Tallberg, A., Pakarinen, S., Leinikka, M., & Huotilainen, M. (2019). Effects of live music therapy on heart rate variability and self-reported stress and anxiety among hospitalized pregnant women: A randomized controlled trial. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 28(1), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2018.1546223.

Warth, M., Kessler, J., Hillecke, T. K., & Bardenheuer, H. J. (2016). Trajectories of terminally ill patients’ cardiovascular response to receptive music therapy in palliative care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 52(2), 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPAINSYMMAN.2016.01.008.

Zhao, K., Bai, Z. G., Bo, A., & Chi, I. (2016). A systematic review and meta-analysis of music therapy for the older adults with depression. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(11), 1188–1198. https://doi.org/10.1002/GPS.4494.