FIGURE 1 | Participant flowchart.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2024) 10(2):221–234 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2024/10/18 |

Poetry in Peer Groups to Reduce Suicide in a Latin American Context

拉丁美洲诗歌干预同辈团体对减少自杀的研究

1Universidad de Manizales, Faculty of Health Sciences, Colombia

2Universidad de Caldas, Faculty of Health Sciences, Colombia

Abstract

The objective of this study was to determine the impact on the reduction of mental health problems in adolescents who participate in support groups with poetry, those who participate in groups with other methodologies, and those who do not participate in support groups. This community trial, which performed in 2021, included 1252 adolescents, of whom 171 showed suicidal risk. Three groups were formed: a support group where poetry was included among the methods, a support group that worked on crafts, and a control group that did not participate in support groups. Greater recovery occurred in adolescents who participated in poetry. Recovery strategies can include artistic elements in their methodologies to increase effectiveness.

Keywords: self-help group, art therapy, mental health, suicide adolescents

摘要

这项研究的目的是确定参加诗歌支持团体、参加运用其它方法的团体以及不参加支持团体对减少青少年心理健康问题的影响。这项社区试验于 2021 年进行, 1252 名青少年参加,其中171人显现出自杀风险。参与者组成了三个团体:一个运用多种方式且包含诗歌的支持团体、一个运用手工艺的支持团体和一个不参加支持团体的对照组。参与诗歌支持团体的青少年康复率更高。康复策略可以在其方法中加入艺术元素,以提高有效性。

关键词: 自助团体, 艺术治疗, 精神健康, 青少年自杀

Introduction

Mental health disorders in children and adolescents have been increasing (Campisi et al., 2020; Lannoy et al., 2022). According to the World Health Organization (2022), one in four children and adolescents has had a mental health diagnosis in the last year. During the COVID-19 pandemic, mental health problems increased, given the containment measures taken to manage the pandemic, where social dynamics changed, impacting socialization and increasing anxiety, depression, and stress disorders (Campisi et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2021).

One way to intervene in the situation described above are group and community strategies (Ngai et al., 2021; Patel et al., 2018), which provide people with a unique sense of community, empowerment, acceptance, self-determination, confidence, greater self-esteem, and recognition of their rights (Agudelo-Hernández et al., 2024; Sample et al., 2018). Although there is no clear consensus on the definition of mutual aid groups (MAGs), these have been defined as groups where mutual support is provided among peers on a voluntary basis with face-to-face or virtual meetings, responding to a problem or situation, social or shared health, and where group control remains in the hands of peers (Agudelo-Hernández et al., 2024).

Therefore, creating strategies that intervene in a timely and continuous manner with the real mental health needs of children and young people is a priority (Membride, 2016). This can be achieved through various models of social participation and research-based approaches, framed in policies that contextualize the problems (Patel et al., 2018). In this sense, MAGs allow the characteristics of the development of children and young people to be reaffirmed, since they provide a facilitating environment, generate empathy, and facilitate the expression of the creative impulse (Agudelo-Hernández et al., 2024). In these group spaces, a psychic space persists where everything is allowed, where possibilities become real, where art occurs as an assemblage of possibilities (Agudelo-Hernández et al., 2024).

The literature has shown a great impact on mental health recovery at the individual (Andersen & Hakemulder, 2024) and group levels (Alfrey et al., 2021). In relation to the above, poetry therapy has been used as a holistic and interdisciplinary treatment, seeking effects of regulation, balance, relief, healing, and integration (Heimes, 2011), and which considers using each person’s language, symbols, and story in individual and community recovery (Mazza & Hayton, 2013).

This therapeutic approach has evolved through the exploration and evaluation of the poetic in a wide range of practice settings (Mazza, 2017). As a health strategy, it has been shown to integrate sensitive and human aspects that are often neglected in classical clinical care (Broderick, 2011), which provides richness and flexibility, enhances participation, and makes it work as a complement to other therapeutic activities (Mazza, 2017). This is how arts was discovered to play an important role in promoting health, treating diseases, and, in some cases, protecting against disease recurrence (Fancourt & Finn, 2019; Nyssen et al., 2016).

From Theory to Implementation

Mental health recovery according to globally accepted elements focuses on the person and the community as the axis of recovery (Patel et al., 2018). However, in Latin America, great difficulties have been identified in the implementation of these strategies among children and adolescents (Agudelo-Hernández & Guapacha Montoya, 2023). Among these identified difficulties are sociodemographic barriers (Ghasemi et al., 2021), absence of group or community strategies that contribute to recovery (Sjollema & Hanley, 2014), and absence of evaluation and implementation methods that prevent their implementation, dissemination, and sustainability (Agudelo-Hernández & Rojas-Andrade, 2023; Heimes, 2011).

Psychotherapeutic interventions with poetic elements do not escape these implementation difficulties. Although there are positive associations between this type of therapy and well-being, the evidence is limited, and the elements and mechanisms through which poetry could explain its effect on psychotherapeutic processes are not clear (Alfrey et al., 2021).

Elements of psychological therapy, such as psychodynamic theory or cognitive-behavioral therapy, have been proposed as mechanisms of change (Mazza, 2017). Some authors have identified therapeutic factors that could be mechanisms of change, including expression, aesthetics, embodiment, pleasure of play, and ritual (Gabel & Robb, 2017; Wilson & Dymoke, 2017). However, it has been concluded that more research is needed to examine change processes (Heimes, 2011; Ramsey-Wade & Devine, 2018), especially those related to group processes (Agudelo-Hernández & Rojas-Andrade, 2023).

A review by Alfrey et al. (2021) found that these components could be described as involving, feeling, exploring, connecting, and transferring, which reaffirms what Mazza (2017) described. Furthermore, it was found to be a valid and useful tool for research and practice (Alfrey et al., 2021). Despite this, this review concludes that more research is required to test the model empirically.

Hypotheses

The methodological elements of poetry therapy could contribute to the recovery of mental health. However, more empirical evidence is required to better understand its functioning and allow these elements to be integrated into evidence-based practices. Based on the above, the present study aimed to determine the impact on reducing mental health problems, such as low resilience, affective and behavioral symptoms, and hopelessness, in adolescents who attend support groups with poetry, on those who attend groups with other methodologies, and those who do not attend support groups. Additionally, we also aimed to describe some poetic elements and their integration of nuclear components of mutual aid. As a hypothesis, we propose that the groups in whom poetic elements are used experience greater impact on the recovery of mental health than those groups in whom other methods are used and those in whom only clinical care is provided.

Methods

A non-controlled pre-post quasi-experimental study was carried out within the framework of the “Manizales Chooses Life” strategy to reduce suicidal behavior in children and adolescents of the municipalities of Manizales, the second region of Colombia with the highest rate of suicidal behavior (Gómez-Restrepo et al., 2016).

Participants and Procedure

The participants of the framework strategy were 1252 adolescents (age 10–18 years) belonging to educational institutions and their main caregivers. The inclusion criteria were participation in the strategy, as indicated by signed informed consent and assent, and with suicidal risk. There were no exclusion criteria.

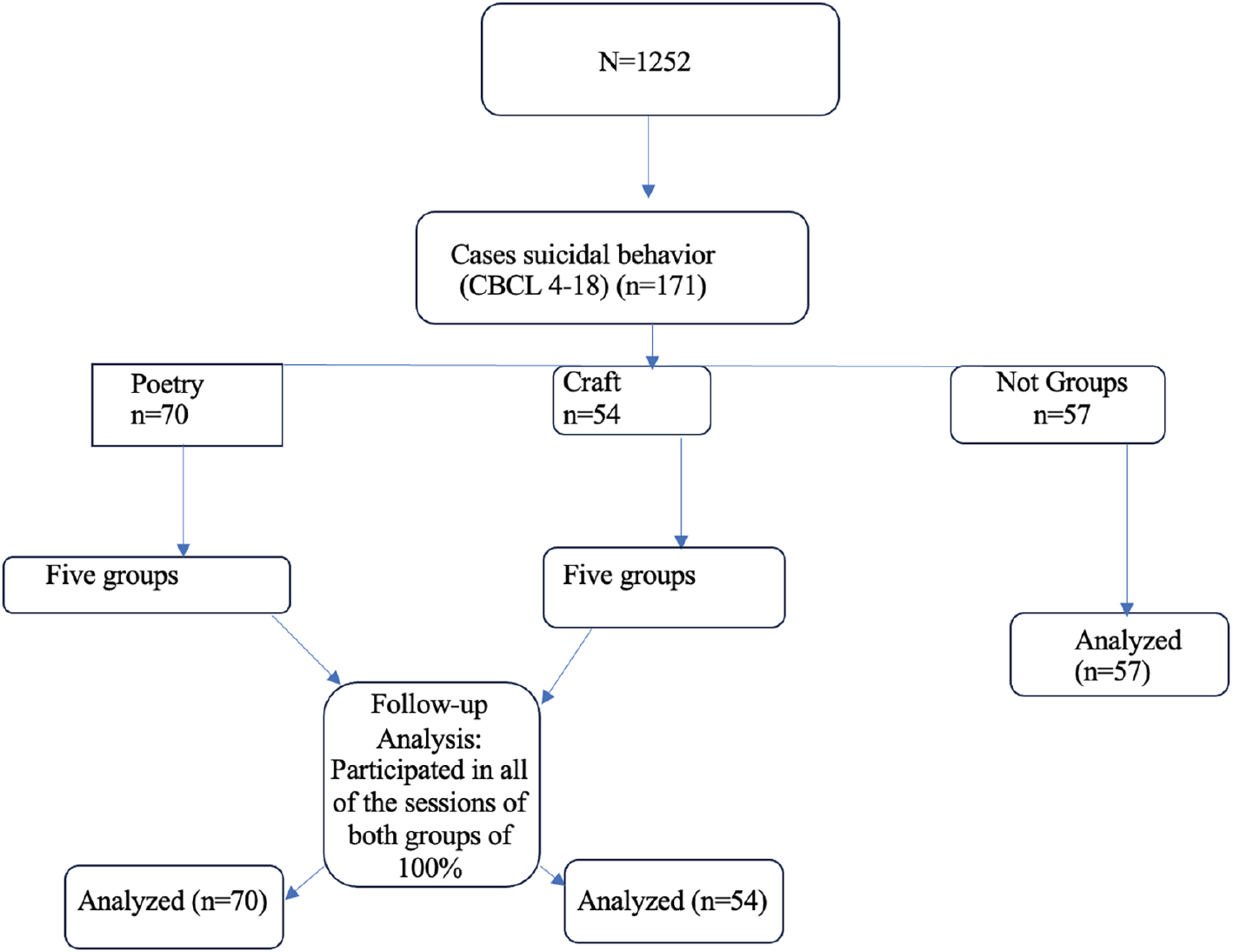

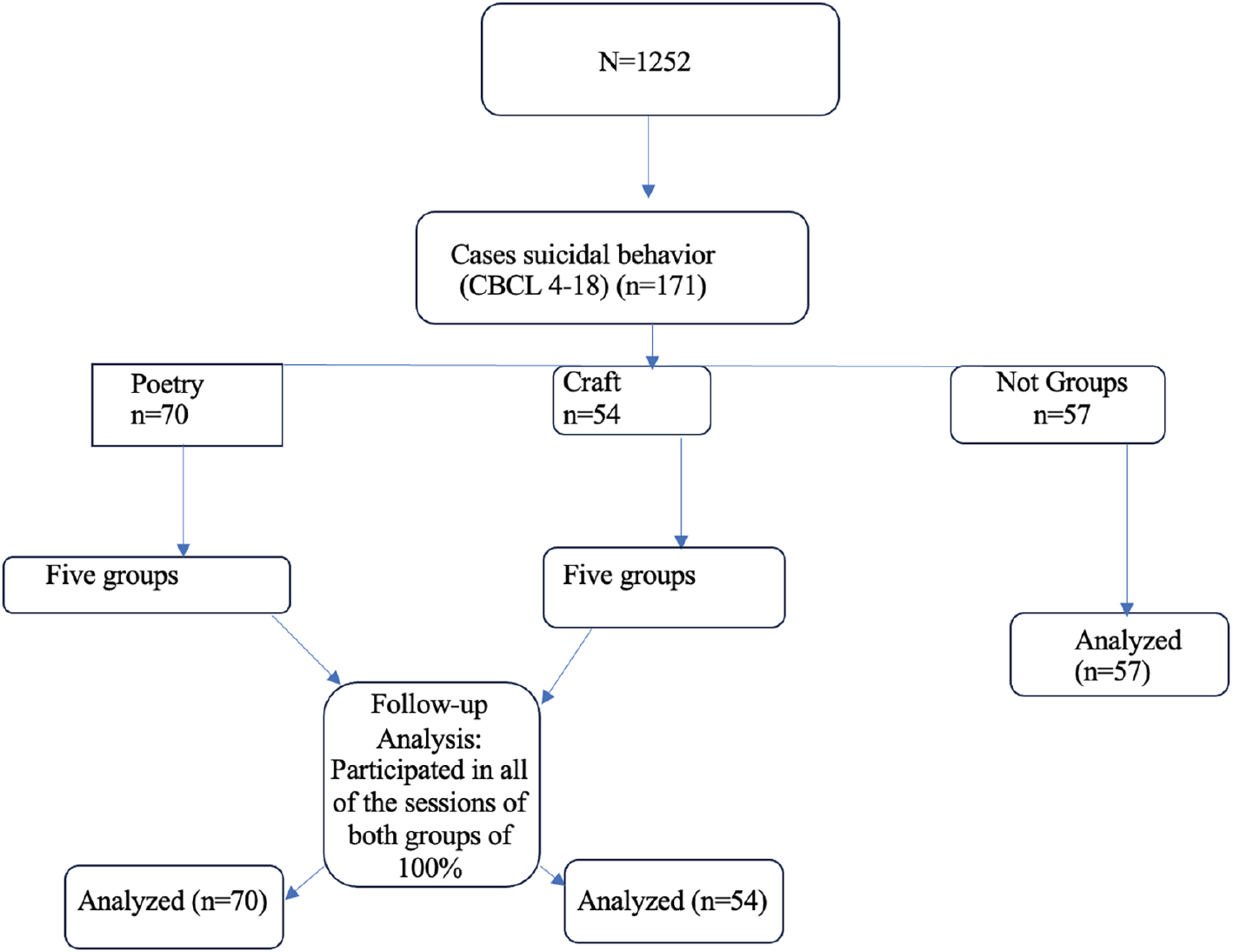

Of the total sample, 171 adolescents showed suicidal risk. All families, as part of the strategy, received care based on the Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) for 3 months. This program has shown effectiveness in low- and middle-income countries (Keynejad et al., 2021), and joining the group was voluntary. Apart from this clinical care, three groups were selected based on the choice of the adolescents and their families (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 | Participant flowchart.

The first group (poetry intervention) consisted of a support group that proposed poetry and creative writing as themes. The second group (crafting intervention) consisted of a support group with crafts as a theme. These support groups were comprised subgroups of 8 to 12 people and were held in the school environment, which allowed high adherence to the process. The third group chose not to belong to any support group, but they received clinical treatment from the mhGAP.

Both groups (poetry and crafts) applied the core components of support and MAGs, determined through the Mutual Aid Scale (Agudelo-Hernández & Rojas-Andrade, 2023), validated in a similar population. To ensure fidelity in the application of the components in the teams that carried out the MAGs, the score for all teams was in the highest quartile, with no significant differences between the leaders of the support groups. These leaders had psychology or social work as their profession. There were eight sessions of the group process, and the same components were applied in both occupational therapy and poetry sessions (Table 1).

TABLE 1 | Themes Addressed in the Support Groups

| Session | Component definition |

|---|---|

| Active agency | The enhancement of capabilities or translation of these capabilities into actions that arise from the engagement in the support group |

| Coping strategies | The support group provides individuals with techniques that are learned or strengthened, enabling them to better cope with challenging personal situations |

| Emotion recognition/management | The identification of personal difficulties through group dynamics, facilitating the recognition of individual challenges related to mental health |

| Problem solving | Group contribution that occurs by identifying individual coping strategies in group dynamics that had not been considered before and that are important for recovery |

| Supportive interaction | Relationships in a group that are perceived as horizontal and generating trust between members; active exploration of the same people of group actions for mental health with the intention of relating to other people |

| Identity construction | Process of identifying characteristics of one’s own personality; identification of parental roles, such as father, mother, brother, etc., are included |

| Trust | Reception of particularities of each person without criticism or pointing out those that the person perceives as negative in himself |

| Social networks | Recognition of the group as a tool that provides the person with constant availability for their difficulties, beyond specific meetings |

Adapted from Agudelo-Hernández & Rojas-Andrade (2024).

In the poetry intervention group, the poets were proposed by the participants. These were incorporated by the main researcher into the core components of the support groups and organized by cluster according to the theme: cluster 1, recognition and emotional management: Alejandra Pizarnik and Fernando Pessoa; cluster 2, problem-solving techniques: Pablo Neruda and Vicente Huidobro; cluster 3, coping strategies: Arthur Rimbaud and Charles Baudelaire; cluster 4, supportive interactions and trust: Gonzalo Arango, Raúl Gómez Jattin, and Walt Whitman; cluster 5, support in the construction of identity: Jorge Luis Borges; cluster 6, strengthening social networks and strengthening agency capacity: Mario Benedetti. The structure of the session was based on the proposal of Mazza and Hayton (2013), which identifies the role of receptive, expressive, and symbolic aspects of poetry: A poem was introduced in the session by the authors chosen by the participants; they wrote reactions, and emerging metaphors were allowed.

The measurement instrument consisted of sociodemographic data, adverse events in childhood, the Beck Hopelessness Scale (Hermosillo-de-la-Torre et al., 2020), and the Connor and Davidson Resilience Scale (Riveros-Munévar et al., 2017), in addition to the Child Behavior Checklist 4–18 (CBCL/4–18) (Agudelo-Hernández et al., 2023), which served to determine, according to its domains, sadness, language problems, somatic symptoms, sleep problems, anxiety, irritability, behavioral problems, adverse school experience, and suicidal behavior. Based on the cutoff points of each instrument, a dichotomous variable on the risk for the study variables was generated.

Within the poetry intervention group, adolescents were asked about the most influential poets in recovering from different mental health risks. Through open questions, they were asked what they considered the recovery mechanism, which was subsequently categorized.

Analysis

SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used. The results of the Shapiro-Wilk test indicated that the measurement data for the psychological variables did not follow a normal distribution; hence, non-parametric inferential tests were used. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for intergroup comparisons, and the Wilcoxon test was used for intragroup comparisons. Furthermore, the effect size was determined by the Mann-Whitney U test. Bivariate correlations were used between the poetry clusters and the risk variables, especially the Spearman test.

Results

Table 2 presents the sociodemographic variables, and no significant differences were observed except in the hours of reading in each group (p<0.001).

TABLE 2 | Intergroup Comparisons Before the Intervention

| Variable | Poetry intervention (n=70) | Crafting intervention (n=54) | No group intervention (n=47) | Significance* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.002 | |||

| Female | 42.86 | 55.56 | 70.21 | |

| Male | 47.14 | 62.65 | 29.79 | |

| Age range | 0.094 | |||

| 10–14 years | 77.14 | 77.78 | 55.32 | |

| 15–18 years | 22.86 | 22.22 | 44.68 | |

| Learning problems | 0.161 | |||

| Yes | 45.71 | 46.3 | 29.79 | |

| Not | 54.29 | 53.7 | 70.21 | |

| Sleeping problems | 0.065 | |||

| Yes | 47.14 | 51.85 | 29.79 | |

| Not | 52.86 | 48.15 | 70.21 | |

| Somatic symptoms | 0.350 | |||

| Yes | 18.57 | 24.07 | 12.77 | |

| Not | 81.43 | 75.93 | 87.23 | |

| Anxiety | 0.276 | |||

| Yes | 50 | 53.7% | 38.3 | |

| Not | 50 | 46.3 | 61.7 | |

| Hopelessness | 0.664 | |||

| Yes | 50 | 46.3 | 55.32 | |

| Not | 50 | 53.7 | 44.68 | |

| Irritability | 0.204 | |||

| Yes | 50 | 48.15 | 34.04 | |

| Not | 50 | 51.85 | 65.96 | |

| Low resilience | 0.664 | |||

| Yes | 50 | 46.3 | 55.32 | |

| Not | 50 | 53.7 | 44.68 | |

| Adverse school experience | 0.668 | |||

| Yes | 44.29 | 42.59 | 51.06 | |

| Not | 55.71 | 57.41 | 48.94 | |

| Sadness | 0.276 | |||

| Yes | 50 | 53.7 | 38.3 | |

| Not | 50 | 46.3 | 61.7 | |

| Behavior problems | 0.594 | |||

| Yes | 44.29 | 51.85 | 42.55 | |

| Not | 55.71 | 48.15 | 57.45 | |

| Adverse events | 0.079 | |||

| Yes | 40 | 53.7 | 31.91 | |

| Not | 60 | 46.3 | 68.09 | |

| Average reading hours | 3.18 | 2.45 | 2.13 | <0.001 |

Values are presented as percentage, except for average reading hours.

*Statistical Significance: p < 0.05.

After the intervention, there were lower averages in all domains in the poetry intervention group than in the other two groups (Table 3), and statistically significant differences were observed (p<0.005) for resilience, hope, suicidal behavior, and sadness.

TABLE 3 | Intergroup Comparisons After the Intervention

| Dimensions | Poetry intervention (n=70) | Crafting intervention (n=54) | No group intervention (n=47) | Statistical test* | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sadness | 73.77 | 95.67 | 93.11 | 12.73 | 0.002 |

| Learning problems | 78.88 | 93.08 | 88.47 | 4.52 | 0.104 |

| Resilience | 68.83 | 88.42 | 108.8 | 30.19 | <0.001 |

| Hopelessness | 74.99 | 84.58 | 10402 | 16.97 | <0.001 |

| Somatic symptoms | 84.77 | 87.67 | 85.91 | 0.311 | 0.856 |

| Sleeping problems | 82.54 | 101 | 73.91 | 13.73 | 0.001 |

| Anxiety | 78.94 | 92.42 | 89.15 | 4.62 | 0.397 |

| Irritability | 82.38 | 82.33 | 95.61 | 4.62 | 0.100 |

| Behavior problems | 85.65 | 83.75 | 89.11 | 0.47 | 0.790 |

| Adverse school experience | 83.60 | 87.08 | 88.33 | 0.58 | 0.757 |

| Decrease suicidal behavior | 108.61 | 77.08 | 62.56 | 41.08 | <0.001 |

Values are presented as averages.

*Kruskal-Wallis test (Degrees of freedom. 2).

Table 4 presents the results of the Mann-Whitney U test for mental health risk variables and intervention effect size. The values of the probability of superiority (pSest) are presented for each of the subscales, showing that when comparing the poetry intervention group with those without group intervention and those in the crafting intervention group. Regarding both group therapeutic processes, a moderate effect size was observed for language problems (pSest=0.42), hope (pSest=0.44), somatic symptoms (pSest=0.48), anxiety (pSest=0.42), irritability (pSest=0.50), behavioral problems (pSest=0.49), and school experience (pSest=0.48). When comparing clinical care without group strategies with the crafting intervention group, a higher effect size is shown in all variables.

TABLE 4 | Results of the Mann-Whitney U Test for Mental Health Risk Variables and Intervention Effect Size

| Risk | P vs. NG |

P vs. C |

C vs. NG |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U | p | pSest | U | p | pSest | U | p | pSest | |

| Sadness | 1273 | 0.003 | 0.39 | 1406 | <0.001 | 0.37 | 1231 | 0.755 | 0.48 |

| Learning problems | 1460.5 | 0.160 | 0.44 | 1576 | 0.037 | 0.42 | 1200.5 | 0.566 | 0.47 |

| Resilience | 876 | <0.001 | 0.27 | 1457 | <0.001 | 0.23 | 966.5 | 0.016 | 0.38 |

| Hopelessness | 1086.5 | <0.001 | 0.33 | 1678 | 0.106 | 0.44 | 980.5 | 0.017 | 0.39 |

| Somatic symptoms | 1623 | 0.828 | 0.43 | 1826 | 0.579 | 0.48 | 1243 | 0.767 | 0.49 |

| Sleeping problems | 1479 | 0.173 | 0.49 | 1482 | 0.011 | 0.39 | 867 | <0.001 | 0.34 |

| Anxiety | 1448.5 | 0.118 | 0.44 | 1592 | 0.038 | 0.42 | 1220.5 | 0.677 | 0.48 |

| Irritability | 1390.5 | 0.058 | 0.42 | 1889 | <0.994 | 0.50 | 1072 | 0.077 | 0.42 |

| Behavior | 1578.5 | 0.646 | 0.48 | 1848 | 0.788 | 0.49 | 1189.5 | 0.498 | 0.47 |

| School experience | 1554 | 0.482 | 0.47 | 1813 | 0.543 | 0.48 | 1250.5 | 0.866 | 0.49 |

| Decrease suicidal behavior | 759 | <0.001 | 0.23 | 1193 | <0.001 | 0.31 | 1053.5 | 0.090 | 0.41 |

P, poetry intervention group; C, crafting intervention group; NG, non-group intervention; p, p-value; U, Mann-Whitney U statistic; pSest, probability of superiority (effect size).

When investigating within the poetry intervention group by the poets addressed in the sessions, correlations were found with the reduction in risk in the mental health variables (Table 5).

TABLE 5 | Correlations in the Poetry Intervention Group Between Addressed Poets and Mental Health Risks After the Intervention

| Improvement variable | Pizarnik | Neruda | Benedetti | Baudelaire | Rimbaud | Huidobro | Borges | Jattin | Pessoa | Whitman |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide risk | 0.293* | 0.183 | –0.123 | 0.101 | 0.068 | 0.161 | 0.213 | 0.019 | 0.172 | –0.007 |

| Significance | 0.014 | 0.128 | 0.31 | 0.408 | 0.574 | 0.183 | 0.076 | 0.873 | 0.154 | 0.954 |

| Sadness | –0.154 | 0.107 | 0.18 | –0.018 | 0.075 | 0.059 | 0.052 | 0.071 | 0.251* | 0.19 |

| Significance | 0.204 | 0.378 | 0.137 | 0.88 | 0.539 | 0.629 | 0.67 | 0.559 | 0.036 | 0.115 |

| Learning | –0.12 | –0.203 | 0.037 | 0.015 | –0.132 | 0.313** | 0.106 | –0.058 | –0.021 | 0.05 |

| Significance | 0.321 | 0.093 | 0.763 | 0.902 | 0.274 | 0.008 | 0.382 | 0.633 | 0.862 | 0.679 |

| Resilience | 0.154 | –0.015 | 0.204 | –0.125 | –0.085 | 0.134 | 0.147 | 0.032 | 0.003 | 0.111 |

| Significance | 0.203 | 0.901 | 0.09 | 0.303 | 0.485 | 0.27 | 0.224 | 0.791 | 0.98 | 0.361 |

| Hope | 0.283* | –0.108 | 0.128 | –0.035 | 0.225 | 0.121 | –0.16 | 0.135 | –0.178 | 0.139 |

| Significance | 0.017 | 0.373 | 0.291 | 0.775 | 0.061 | 0.318 | 0.185 | 0.265 | 0.141 | 0.251 |

| Sleep | –0.026 | –0.122 | –0.136 | 0.069 | –0.151 | 0.015 | –0.059 | –0.118 | 0.054 | –0.121 |

| Significance | 0.833 | 0.315 | 0.261 | 0.568 | 0.212 | 0.903 | 0.628 | 0.329 | 0.658 | 0.32 |

| Somatics | –0.063 | 0.201 | –0.09 | –0.018 | 0.075 | –0.137 | 0.143 | 0.071 | 0.036 | –0.08 |

| Significance | 0.607 | 0.096 | 0.46 | 0.88 | 0.539 | 0.257 | 0.239 | 0.559 | 0.77 | 0.513 |

| Anxiety | 0.124 | 0.088 | –0.118 | –0.176 | –0.12 | 0.146 | 0.023 | –0.099 | 0.032 | –0.105 |

| Significance | 0.306 | 0.47 | 0.332 | 0.144 | 0.323 | 0.229 | 0.852 | 0.413 | 0.791 | 0.385 |

| Irritability | 0.103 | 0.334** | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.153 | 0.088 | 0.403** | 0.105 | 0.292* | 0.05 |

| Significance | 0.395 | 0.005 | 0.364 | 0.323 | 0.207 | 0.468 | 0.001 | 0.389 | 0.014 | 0.679 |

| Behavior | 0.108 | 0.163 | –0.031 | 0.267* | –0.061 | –0.02 | 0.441** | 0.398** | 0.272* | –0.075 |

| Significance | 0.375 | 0.179 | 0.798 | 0.025 | 0.619 | 0.867 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.023 | 0.538 |

| School | –0.015 | 0.075 | 0.071 | 0.102 | 0.277* | –0.016 | 0.072 | 0.158 | –0.198 | 0.086 |

| Significance | 0.905 | 0.54 | 0.557 | 0.4 | 0.02 | 0.898 | 0.553 | 0.191 | 0.101 | 0.48 |

The correlation is significant at the *0.05 and **0.01 levels (both two-sided).

A poem from one of the sessions is presented and constructed using the exquisite cadaver method, which consists of a form of collective writing, on a specific topic, successively, and involving all participants.

Recognition and Emotional Management

Based on Alejandra Pizarnik and Fernando Pessoa:

Do you want me to tell you how it hurts?

I can’t, but look at my eyes.

Do you want me to say where it hurts?

I can’t, but look at the scars on my arms.

Do you want me to tell you why it hurts?

I can’t, but look at the story of my childhood.

Do you want me to tell you how long it hurts?

I can’t, but look at my damaged watch.

Do you want me to tell you what relieves me?

I can’t, but look at you looking into my eyes.

When investigating the mechanisms of change in the participants, the most frequent categories are the following: defining emotions, knowing how to define pain through others, learning to solve problems, learning how to support others, and finding how to occupy free time.

Discussion

There is added difficulty in implementing effective interventions that are accepted by the adolescents themselves, but strategies that include poetic methods showed promise. For this reason, the present research hypothesized a greater reduction in mental health problems in a support group with poetic elements than in support group with other methods and in other adolescents without attendance of support groups. This hypothesis was confirmed, and relationships were also shown between poets and the nuclear components of the support groups.

Other studies have reported positive results with similar methods for people with aphasia, addictions, dementia, eating disorders, grief, homelessness, psychosis, sexual dysfunction, and survivors of intimate partner violence (Alfrey et al., 2021). Similarly, the use of art in psychotherapeutic interventions has been shown to reduce physical symptoms and mental health problems (Jensen & Bonde, 2018).

The components used in group interventions have shown increased quality of life, social networks, hope, strengthening of identity, and agency capacity (Agudelo-Hernández et al., 2024), like other interventions. Artistic practitioners in psychotherapy have shown greater ability to solve problems, fewer negative feelings, higher quality of life, greater well-being, reduced anxiety, better understanding of one’s own body, less agitation, positive distractions, greater social interaction, less stress, greater confidence and sense of self-esteem, lower levels of depression, greater sense of hope, and greater ability to connect with valued parts of oneself (Jensen & Bonde, 2018). The stated components are reaffirmed by the present investigation.

As for the poets, a new interpretation of them is proposed through the group. This is the case of the poetry of Alejandra Pizarnik and Fernando Pessoa (poets with a biography and a work with pain and suffering) which was associated with a significant improvement in those adolescents who chose them in the groups. In this regard, there may be a connection between the reader and the text, in terms of relevance or personal resonance (Kuzmičová & Bálint, 2019), which may be an underlying mechanism for the creation of a new meaning (Whiteley & Canning, 2017).

However, readers find themselves participating in an unconventional flow of feelings through which they realize something they have that had not been previously experienced; thus, factors such as familiar themes, one’s own perspective, location, and feeling, come into play for a new interpretation (Andersen & Hakemulder, 2024; Wilson & Dymoke, 2017). The above is in relation to the dynamics of support groups and the images that are shared around poetry. This contributes to the feeling of everyone being in the same boat, provides cohesion to group processes, and facilitates the creation of new possibilities of life and recovery (Agudelo-Hernández et al., 2024).

The superiority of group strategies over conventional mental health care has been demonstrated (Patel et al., 2018), especially in adolescents (Agudelo-Hernández et al., 2024; Roach, 2018). In this sense, other authors pointed out that this impact on mental health has been demonstrated when poetic elements are used (Agudelo-Hernández & Guapacha Montoya, 2023; Billington, 2020; Billington et al., 2013), especially in the current population of the study (i.e., adolescents with suicidal behavior) (Agudelo-Hernández & Guapacha Montoya, 2023). However, these studies had not compared this intervention with other evidence-based practices, such as mhGAP (Keynejad et al., 2021) and support groups with other methodologies (Pan American Health Organization, 2022), which can be considered a strength of the present investigation.

This study has limitations. First, there were initial differences in the love of reading, which can contribute to a type I error. However, the need to promote reading as a recovery factor and a good prognosis in the recovery of mental health has been pointed out by other authors (Andersen & Hakemulder, 2024). Likewise, ethical considerations and the scope of the intervention (health project) did not allow for a randomized design, which is not recommended when using support groups and constitutes a challenge to address (Agudelo-Hernández et al., 2024; Sample et al., 2018).

Therefore, there is a need for future studies to complement other methodologies, ideally longitudinal studies that not only evaluate the short- and medium-term effects of therapeutic interventions but also the long-term effects and in other population groups, such as indigenous communities, those with sensory disability, etc. Studies with mixed approaches could better address ontological aspects of the recovery networks that are formed in support and MAGs (Agudelo-Hernández et al., 2023).

Conclusion

Low-cost and artistic activities have shown potential in promoting mental health and can constitute group recovery strategies, which are recommended by current evidence. In the present study, support groups showed a superior effect than conventional clinical care. Furthermore, those who linked poetry in their processes had a greater response than those who had other types of activities, even when the fidelity of the core components of the support groups by the professionals was maintained. Based on growing evidence of arts participation as a tool to improve mental health well-being and in line with global health challenges, arts activities should be more available in health strategies.

Acknowledgement

We thank the adolescents of Manizales Choose Life who participated in this study.

About the Authors

Felipe Agudelo-Hernández, MD (Child and Adolescent Psychiatry), PhD (Social Sciences, Childhood and Youth), is an advisor for the implementation of the mental health public policy in Colombia and the community-based rehabilitation strategy for the capital cities of Ibero-America. He has led national risk management strategies for adolescents and children at risk of suicide, with an intercultural approach. He is a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Manizales and with a specialization in pediatrics at the University of Caldas.

Mariana Rojas Echeverry, MD, forms humanitarian aid groups in the mental health division. She leads a poetry support group in the city of Manizales, and has lived experience in mental health.

Matías Mejía Chaves is the leader of the mutual aid group “Manizales Elige la Vida.” He works in a rural area, where he writes poetry and leads community health strategies, and has lived experience in mental health.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: afagudelo81703@umanizales.edu.co; Tel.: +57-314-651-7362; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8356-8878.

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Agudelo-Hernández, F., & Guapacha Montoya, M. (2023). Poetry in youth mutual aid groups for recovery in rural and semi-urban environments. Arts and Health, 16(3), 340–357. DOI: 10.1080/17533015.2023.2273490.

Agudelo-Hernández, F., & Rojas-Andrade, R. (2024). Design and validation of a scale of core components of community interventions in mental health. International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 39(1), 36–47. DOI: 10.1002/hpm.3711.

Agudelo-Hernández, F., Vélez-Botero, H., & Guapacha-Montoya, M. (2023). Propiedades psicométricas del Child Behavior Checklist 4-18 (CBCL/4-18) en una muestra semiurbana y rural de Caldas en el 2021. Médicas UIS, 36(3), 145–162. DOI: 10.18273/revmed.v36n3-2023014.

Agudelo-Hernández, F., Peralta Duque, B. d. C., & Rojas-Andrade, R. (2024). The pluralistic ontology in youth groups for mental health. Journal of Psychosocial Studies, 17(2), 135–154. DOI: 10.1332/14786737Y2024D000000023.

Alfrey, A., Field, V., Xenophontes, I., & Holttum, S. (2021). Identifying the mechanisms of poetry therapy and associated effects on participants: A synthesised review of empirical literature. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 75, 101832. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2021.101832.

Andersen, T. R., & Hakemulder, F. (2024). “The poem has stayed with me”: Continued processing and impact from Shared Reading experiences of people living with cancer. Poetics, 102, 101847. DOI: 10.1016/j.poetic.2023.101847.

Billington, J. (2020). Reading and mental health. Palgrave Macmillan.

Billington, J., Davis, P., & Farrington, G. (2013). Reading as participatory art: An alternative mental health therapy. Journal of Arts & Communities, 5(1), 25–40. DOI: 10.1386/jaac.5.1.25_1.

Broderick, S. (2011). Arts practices in unreasonable doubt? Reflections on understandings of arts practices in healthcare contexts. Arts and Health, 3(2), 95–109. DOI: 10.1080/17533015.2010.551716.

Campisi, S. C., Carducci, B., Akseer, N., Zasowski, C., Szatmari, P., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2020). Suicidal behaviours among adolescents from 90 countries: A pooled analysis of the global school-based student health survey. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1102. DOI: 10.1186/s12889-020-09209-z.

Fancourt, D., & Finn, S. (2019). What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A Scoping Review. Retrieved October 10, 2019, from https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/329834/9789289054553-eng.pdf.

Gabel, A., & Robb, M. (2017). (Re)considering psychological constructs: A thematic synthesis defining five therapeutic factors in group art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 55, 126–135. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2017.05.005.

Gómez-Restrepo, C., Aulí, J., Tamayo Martínez, N., Gil, F., Garzón, D., & Casas, G. (2016). Prevalencia y factores asociados a trastornos mentales en la población de ninños colombianos, Encuesta Nacional de Salud Mental (ENSM) 2015. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría, 45(Suppl. 1), 39–49. DOI: 10.1016/j.rcp.2016.06.010.

Ghasemi, E., Majdzadeh, R., Rajabi, F., Vedadhir, A., Negarandeh, R., Jamshidi, E., Takian, A., & Faraji, Z. (2021). Applying intersectionality in designing and implementing health interventions: A scoping review. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1407. DOI: 10.1186/s12889-021-11449-6.

Jensen, A., & Bonde, L. O. (2018). The use of arts interventions for mental health and wellbeing in health settings. Perspectives in Public Health, 138(4), 209–214. DOI: 10.1177/1757913918772602.

Heimes, S. (2011). State of poetry therapy research (review). The Arts in Psychotherapy, 38, 1–8.

Hermosillo-de-la-Torre, A. E., Méndez-Sánchez, C., & González-Betanzos, F. (2020). Evidencias de validez factorial de la Escala de desesperanza de Beck en español con muestras clínicas y no clínicas. Acta Colombiana De Psicología, 23(2), 148–169. DOI: 10.14718/ACP.2020.23.2.7.

Keynejad, R., Spagnolo, J., & Thornicroft, G. (2021). WHO Mental Health Gap Action programme (mhGAP) intervention guide: Updated systematic review on evidence and impact. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 24(3), 124–130. DOI: 10.1136/ebmental-2021-300254.

Kuzmičová, A., & Bálint, K. (2019). Personal relevance in story reading: A research review. Poetics Today, 40(3), 429–451. DOI: 10.1215/03335372-7558066.

Lannoy, S., Mars, B., Heron, J., & Edwards, A. C. (2022). Suicidal ideation during adolescence: The roles of aggregate genetic liability for suicide attempts and negative life events in the past year. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 63(10), 1164–1173. DOI: 10.1111/jcpp.13653.

Ma, L., Mazidi, M., Li, K., Li, Y., Chen, S., Kirwan, R., & Wang, Y. (2021). Prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 293, 78–89. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.021.

Mazza, N. (2017). Poetry therapy: Theory and practice (2nd ed.). Routledge. DOI: 10.4324/9781315748740.

Mazza, N. F., & Hayton, C. J. (2013). Poetry therapy: An investigation of a multidimensional clinical model. Arts in Psychotherapy, 40(1), 53–60. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2012.10.002.

Membride, H. (2016). Mental health: Early intervention and prevention in children and young people. British Journal of Nursing, 25(10), 552–557. DOI: 10.12968/bjon.2016.25.10.552.

Ngai, S. S., Cheung, C. K., Ng, Y. H., Shang, L., Tang, H. Y., Ngai, H. L., & Wong, K. H. (2021). Time effects of supportive interaction and facilitator input variety on treatment adherence of young people with chronic health conditions: A dynamic mechanism in mutual aid groups. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3061. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph18063061.

Nyssen, O. P., Taylor, S. J. C., Wong, G., Steed, E., Bourke, L., Lord, J., & Meads, C. (2016). Does therapeutic writing help people with long-term conditions? Systematic review, realist synthesis and economic considerations. Health Technology Assessment, 20(27), 1–367. DOI: 10.3310/hta20270.

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). (2022). Servicios de salud mental de apoyo entre pares: Promover los enfoques centrados en las personas y basados en los derechos. Washington, DC: OPS.

Patel, V., Saxena, S., Lund, C., Thornicroft, G., Baingana, F., Bolton, P., & UnÜtzer, J. (2018). The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet, 392(10157), 1553–1598. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X.

Ramsey-Wade, C. E., & Devine, E. (2018). Is poetry therapy an appropriate intervention for clients recovering from anorexia? A critical review of the literature and client report. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 46(3), 282–292. DOI: 10.1080/03069885.2017.1379595.

Riveros-Munévar, F., Bernal-Vargas, L., Bohórquez-Borda, D., Vinaccia-Alpi, S., & Margarita-Quiceno, J. (2017). Análisis psicométrico del Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC 10) en población universitaria colombiana. Psicología desde el Caribe, 34(3), 161–171.

Roach A. (2018). Supportive peer relationships and mental health in adolescence: An integrative review. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39(9), 723–737. DOI: 10.1080/01612840.2018.1496498.

Sample, L. L., Cooley, B. N., & Ten Bensel, T. (2018). Beyond circles of support: “Fearless”–An open peer-to-peer mutual support group for sex offense registrants and their family members. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62(13), 4257–4277. DOI: 10.1177/0306624X18758895.

Sjollema, S. D., & Hanley, J. (2014). When words arrive: A qualitative study of poetry as a community development tool. Community Development Journal, 49(1), 54–68. DOI: 10.1093/cdj/bst001.

Whiteley, S., & Canning, P. (2017). Reader response research in stylistics. Language and literature. International Journal of Stylistics, 26(2), 71–87. DOI: 10.1177/0963947017704724.

Wilson, A., & Dymoke, S. (2017). Towards a model of poetry writing development as a socially contextualised process. Journal of Writing Research, 9(2), 127–150. 10.17239/jowr-2017.09.02.02.

World Health Organization. (2022). World mental health report: Transforming mental health for all. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338.