FIGURE 1 | Late Summer—Cosmos, by Jane Askey.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2024) 10(2):304–319 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2024/10/16 |

“Art Meets Books”: A Co-produced Arts Pilot Project in Public Libraries

「艺术遇见图书」:公共图书馆中的联合制作艺术先导项目

University of Hertfordshire and Ulster University, United Kingdom

Abstract

The “Art Meets Books” (AMB) pilot project is an innovative partnership involving a charity, Paintings in Hospitals, an art therapist (the present author), and public libraries. AMB delivers arts workshops within public libraries in economically deprived areas in London and the West Midlands and engages people who do not usually access art resources. Through outreach work within Further Education colleges, AMB also engages ethnically diverse participants. AMB integrates a co-production ethos and art-based reflexive practice. An evaluation conducted throughout the project showed that participants (N=49) reported positive experiences of the project. The evaluation identified issues to integrate into the project’s future delivery.

Keywords: arts in libraries, art therapy, co-production, inclusion, inequalities

摘要

“艺术遇见图书” (AMB) 试点项目是一项创新的合作,包括慈善机构、医院中的绘画艺术、一位艺术治疗师 (本文作者) 和公共图书馆。AMB 在伦敦和西米德兰兹郡经济贫困地区的公共图书馆内举办艺术工作坊,吸引通常无法触及艺术资源的人们参加。通过在继续教育学院内的外展工作,AMB 还吸引了不同族群的参与者。AMB 融合了联合制作的价值理念和基于艺术的反思实践。贯穿整个项目进行的评估表明,参与者们 (49人) 报告了对该项目的积极体验。评估还确定了项目未来开展将整合的一些议题。

关键词: 图书馆中的艺术, 艺术治疗, 联合制作, 包容, 不平等

Introduction

The arts are beneficial in the promotion of health and wellbeing, and there is growing evidence of their positive impact on social isolation and loneliness and life-affecting physical and mental health conditions (Fancourt & Finn, 2019). However, there are significant socioeconomic and cultural barriers to accessing the arts that affect disadvantaged, marginalized, or isolated individuals and communities, and it is increasingly recognized that innovative partnerships and approaches to engagement are needed to address these inequalities (Upton–Hansen et al., 2021). The “Art Meets Books” (AMB) project, which is funded by the Arts Council England, aimed to address socioeconomic inequalities that create a barrier to accessing the arts by delivering its program within public libraries, hence its title.

AMB Pilot Project Rationale and Goals

Paintings in Hospitals (PiH) is a charity that “aims to transform the UK’s health by using world-class art to inspire better health and wellbeing for patients, carers, and communities” (Paintings in Hospitals, 2024). PiH has a large collection of artworks that are loaned and exhibited to improve the environment in public health and care settings and that are used for interactive workshops with clients, staff, and carers. AMB was developed in collaboration among the PiH CEO, curators, and library staff over several months to ensure that the project would be relevant to the local communities using public libraries.

Library staff have close links with local people and libraries play an increasingly important role in supporting socioeconomically disadvantaged communities (Libraries Connected, 2022). Libraries provide financial advice, food, clothing and hygiene banks, clubs, and cultural activities and, in winter, warm hubs for people who cannot afford to heat their homes (ibid.). Evidence highlights the link between poverty and increased mental health issues (Knifton & Inglis, 2020), and this is reflected in the number of library users seeking mental health support (Libraries Connected, 2022).

The project aims included the following:

Project Approach and Structure

Pre-project Training

PiH curators, library staff, and art workers were offered two pre-project training sessions delivered by the author, an art therapist, to introduce basic mental health and art therapy skills. The training focused on understanding people’s relationships with and perception of art, as this is not always positive (Huet, 2012). Strategies were shared on how to engage participants who may feel that art is not for them. Basic mental health training was provided that included concepts on trauma and its impact on affect regulation and feeling recognition. Strategies on how to de-escalate potential conflicts with challenging participants were explored. AMB was accessible to all library users, especially those who did not usually connect with art and creative activities or who were isolated and there was no selection process. Considering the increase in mental health needs among library users (Libraries Connected, 2022), this training was welcomed by staff as an essential component of the project.

A Co-curatorial Approach

The project consisted of a series of six creative workshops delivered within three libraries in deprived areas, one in London and two in the West Midlands. The first two workshops focused on a co-curatorial process to select artworks for the project. The PiH curators had selected a “long list” of artworks and invited participants to make a short list of images they wanted to work from in the project. The initial long list was carefully drawn to ensure that people from different cultures could engage with the artworks and that the curators included culturally diverse images of landscapes and still-lives as well as abstract works. The co-curational approach involved the curators sharing as much information as possible about the artworks and the artists and giving a supporting framework to empower participants to express their views, reactions, and opinions. Participants were supported to share personal associations and connections with their own histories and life experiences as well as their esthetic responses to the artworks. This approach supported participants’ engagement and meaning making (Lachapelle et al., 2003). A final decision on the selection was made by all participants by consensus (if this cannot be reached, voting is used).

Four Arts Workshops

Following the two co-curatorial sessions, four art workshops were delivered by artists in health, including a visual artist, a creative writer, and a storyteller, who used the selected artworks as a basis for participants’ creative work. In the first art workshop, participants were invited to pick one painting (Figure 1) and to create a collaborative poem that had words in it from everyone: “They picked Late Summer—Cosmos by Jane Askey. There was good conversation, and I was able to gather plenty of words” (Art Worker)

FIGURE 1 | Late Summer—Cosmos, by Jane Askey.

Collaborative poem: A collaborative poem with the words of edited by Jean Atkin (October 25, 2022).

I like the flowers, they grow white

and pink and yellow and orange

and purple, a real riot of colour.

The vase is glass and I can see

the stems through it.

There is a star-fruit cut in half

on a small plate. It looks

like a plant, it looks fresh.

I like the brightness of the colours.

I call those flowers Queen Anne’s Lace.

There are lemons on a big plate.

I use lemons with food, for cooking.

It’s delicious in rice and I drink

lemon juice every morning.

It’s good for the stomach.

I noticed the clover flowers. When

I was small we picked them, and

sucked them for the sweetness.

Now next to them is a plate

of lemons, tasting sour.

I like the colour of the lemons.

It reminds me of the lemon tree

at home, in my house.

After the rain, the tree scents the house.

The lemon’s smell is a smile.

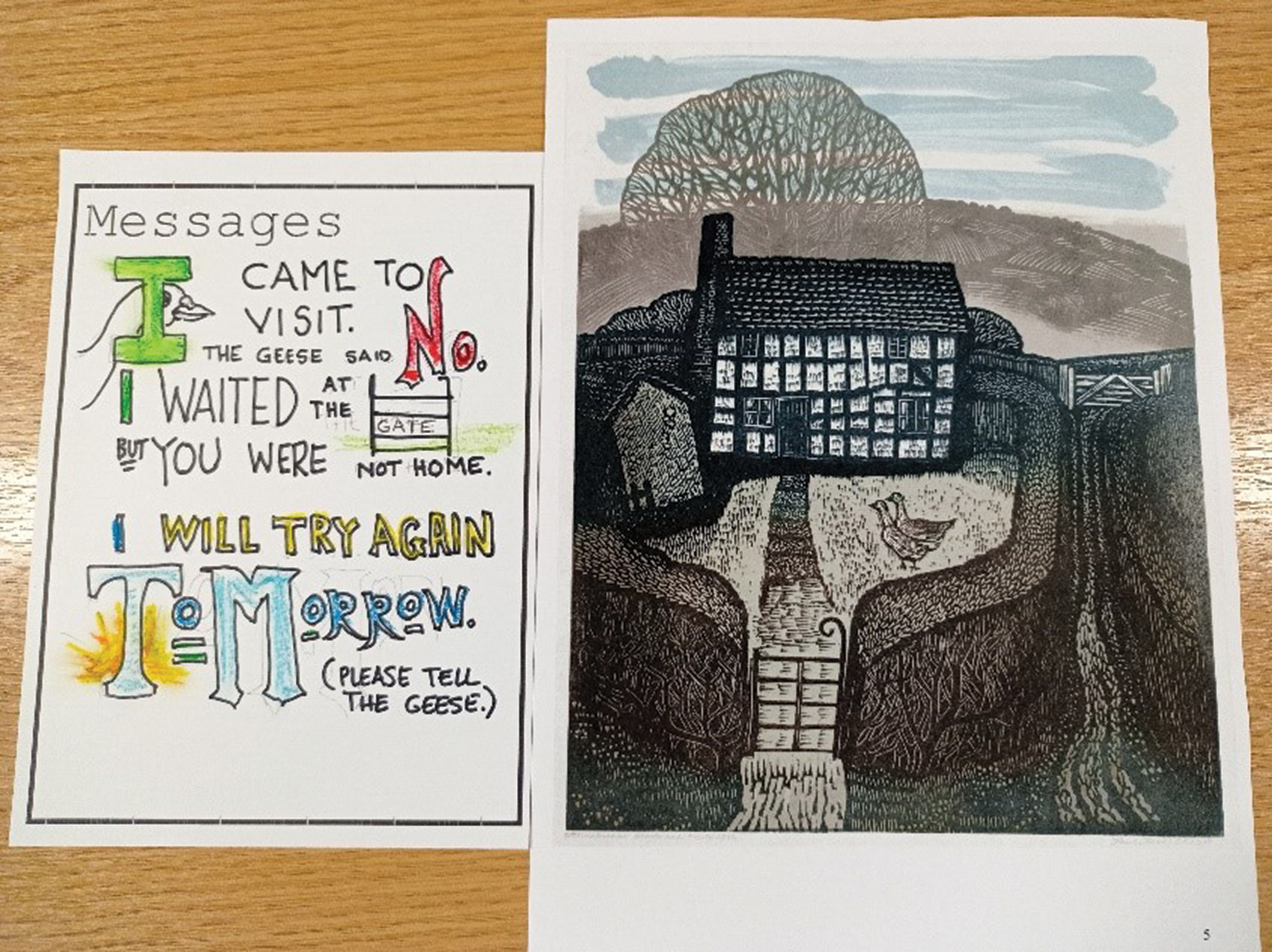

In the second session, participants each chose an artwork and were given a template to do a “message poem” as a response to the image (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2 | A message poem as a response to an artwork from a participant.

I asked them to choose a painting for themselves and showed them an example of a simple “Message” poem. We talked about what sort of message could be written as a response to a painting, and I also suggested they could illustrate the message poem or draw. Then I supplied them with drafting paper, a “Message” poem sheet, colored pencils, oil pastels, a variety of pens and some letter stamps and stamp pads. Everyone worked with great concentration, and they produced some beautiful work. We managed to all go around the table to see and share each other’s work before the end. Everyone was laughing and smiling, and keen to tell me they’d enjoyed the session. (Artist)

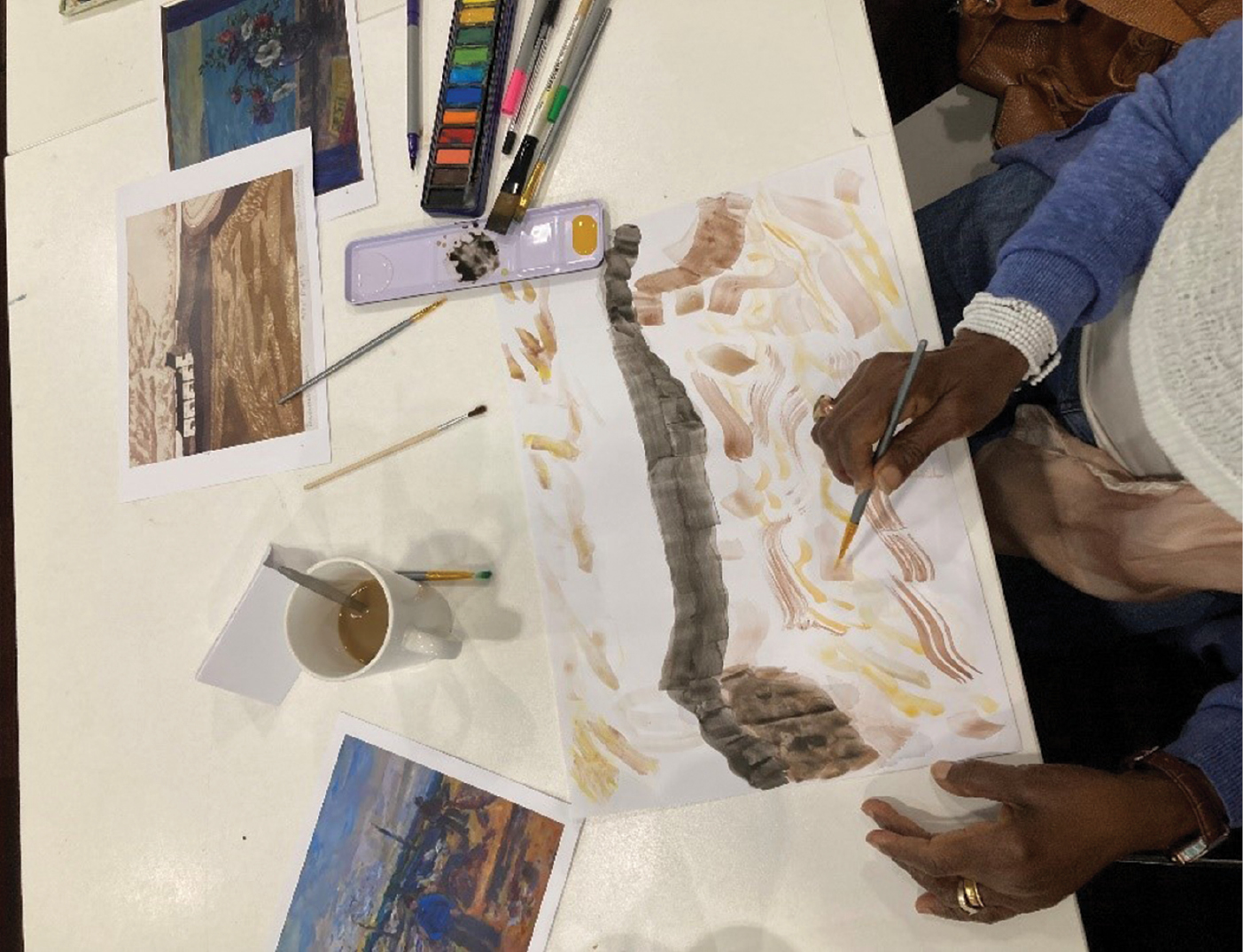

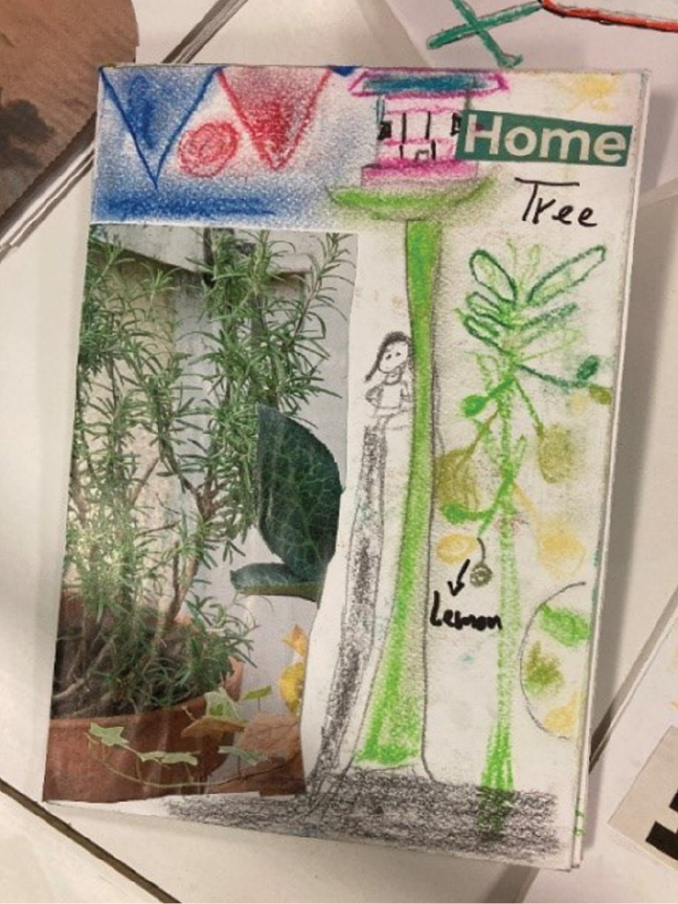

The third workshop encouraged participants to take and blend elements from different artworks to make their own images (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3 | A participant integrates elements of different artworks in her painting.

The final workshop used images to support participants to develop a story and share it verbally in the session. There were no audio or video recordings of these stories, but participants shared their enjoyment of this process at the end of the session.

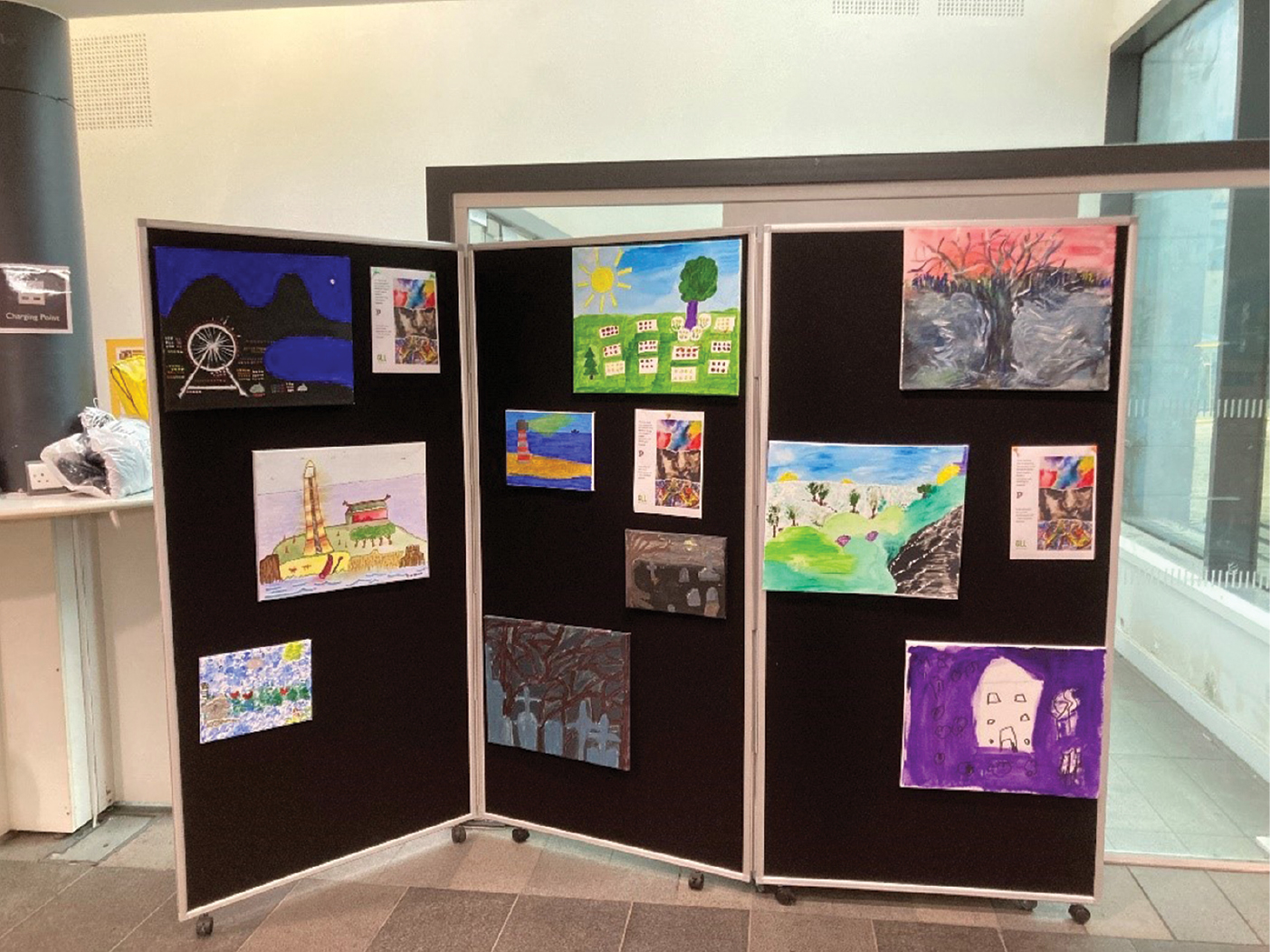

Post-project Exhibitions

As the project was sited in libraries, there were suitable spaces to exbibit a selection of participants’ artworks (Figure 4). Friends and family members were invited, as were other library users. The aim was to make participants feel valued and to support networking among themselves and with library staff.

FIGURE 4 | Participants’ artworks exhibition.

Reflexive Practice Sessions

Reflexive practitioners have a higher level of self-awareness because they are not only able to assess a situation as it is happening and tweak things as they go, but they also have the ability to look at why things are the way that they are and consider the role they are playing in the current outcome. (Parenta, 2019)

Two reflexive practice sessions were conducted with all staff, one mid-way and one after the end of the project. Staff were supported to reflect on their experiences of the project and to share what worked well and which challenges had emerged. They were also encouraged to reflect on their relationship with art and creativity. Additionally, the PiH curators agreed to keep a visual diary during the project.

Evaluation

An evaluation framework was developed in consultation with PiH and the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (NESTA), which the present author used to develop measures to evaluate the main domains. This captured quantitative and qualitative data on participants and their views and reflections on the project, and those of curators, artists, and library staff.

The following five questions form the PiH and NESTA evaluation framework:1

Several measures were developed and used to evaluate the project, including:

Both pre and post project questionnaires had to be simply worded and accessible to ESOL participants (Tables 1 and 2).

TABLE 1 | Pre-project Questionnaire

| We would like to understand your experience of the Art Meets Books project. Below is a short form to share your initial views and experience. Thank you for helping us with this. On a scale of 1 to 5, could you rate the following statements, 1 being the lowest level of agreement and 5 the highest? |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 1 | I visit art galleries and museums occasionally | |||||

| 2 | I do ‘arty’ things sometimes | |||||

| 3 | Art helps me de-stress/relax | |||||

| 4 | I feel confident about discussing art | |||||

| 5 | I feel confident about using art materials | |||||

| 6 | I feel comfortable making art in a group | |||||

| 7 | I feel comfortable in the library | |||||

What are you hoping to get from joining this project? Please write in the box below.

TABLE 2 | Post-project Questionnaire

| We really value your feedback on your experience of the Art Meets Books groups. We would like to understand better what you found helpful and if there are areas which we should improve on. Below is a short form to share your views and experiences. On a scale of 1 to 5, could you rate the following statements, 1 being the lowest level of agreement and 5 the highest? |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 1 | Being in my local library made the sessions accessible | |||||

| 2 | Being somewhere I know made it easier to attend | |||||

| 3 | I enjoyed being part of the group | |||||

| 4 | Participants had a lot in common | |||||

| 5 | The group sessions felt supportive | |||||

| 6 | I learned new helpful things about myself during the project | |||||

| 7 | I learned new helpful things from other participants | |||||

| 8 | I learned new helpful things from staff and facilitators | |||||

| 9 | Mixing looking at artworks and talking was enjoyable | |||||

| 10 | I felt more confident discussing artworks | |||||

| 11 | I learned new things about art during the project | |||||

| 12 | I felt comfortable making art with other people | |||||

| 13 | The project has encouraged me to do ‘arty’ things | |||||

| 14 | Art helped me de-stress/relax | |||||

| 15 | The sessions improved my feelings/mood at the time | |||||

| 16 | The group facilitators were helpful | |||||

| 17 | I found the sessions worthwhile and valuable | |||||

| 18 | I would recommend these sessions to friends and family | |||||

What do you think you got from participating in this project? Any additional thoughts/feedback? Please write in the box below.

Summary of Findings

Diversity and Inclusion

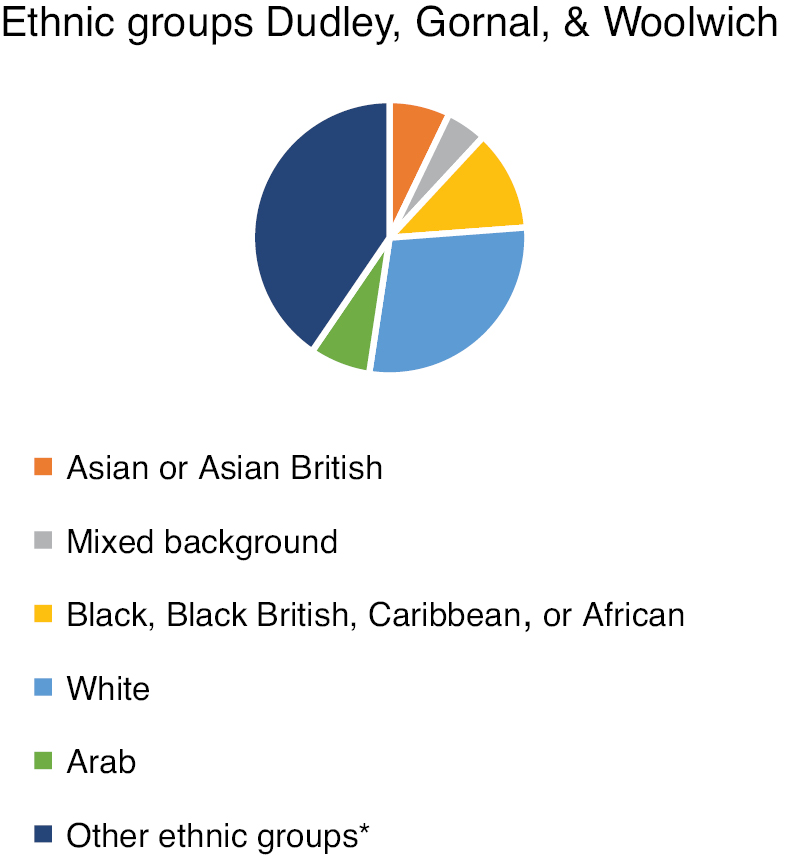

Data analysis of registration forms and pre project questionnaires shows that the project succeeded in including an ethnically diverse group of participants (N=49) who were 29% from white UK backgrounds and 71% from other backgrounds (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5 | Participants’ ethnicities.

*Other ethnic groups include Iraqis, Kurdish, Yemenis, Afghans, Syrians, Eritreans, Bangladeshis, Iranians, etc.

Participants were generally more ethnically diverse than the local population. This was due to active outreach work by the PiH curators with Further Education (FE) colleges and including students learning English as a second or other language (ESOL).

The library setting was key to inclusion and engagement. At the start of the project, 89% of participants reported feeling comfortable joining the project in a library, and this increased to 98% at the end. In pre-project questionnaires, several expressed the hope that the project would contribute to improving their English, a skill essential to understanding a new culture, and accessing employment.

The project engaged 64% of participants who did not visit art galleries or museums. Pre-pandemic data show that from 2018 to 2019, 50.2% of people aged 16 years and older had visited a museum or gallery at least once in the past year (Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, 2020). Participants in this project reported below-average engagement with visiting art galleries or museums.

Quality of Engagement

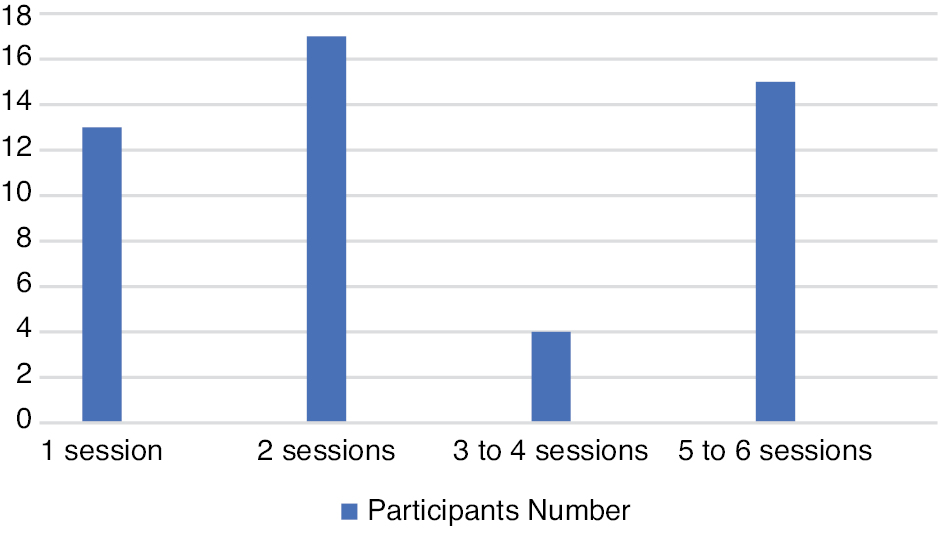

Data on attendance were compiled from registers. There were no criteria regarding regular or minimum attendance, and new participants could join in at any stage of the project. Nevertheless, more than a third of the 49 participants attended between 3 to 6 sessions (6 being the maximum number of sessions delivered), and most attended more than one session, a healthy record for community-based projects with voluntary participation (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6 | Number of sessions attended by participants.

Feedback forms questions aimed to rate participants’ experience of their engagement in and enjoyment of the sessions, and 95% of respondents agreed that the workshops had been enjoyable and supportive, and 89% reported having learned something new about art. The depth of participants’ engagement is reflected in their creative outputs and their contributions to the end-of-project exhibitions. Artists who led art-based, poetry, and creative writing workshops also commented on how engaged participants were with the artworks, and that these offered a strong springboard into creative exploration.

How did Participants Feel about the Artworks and Creative Activities?

I thought no, art is not for me, but doing the course has changed my mind completely about how I feel about art. (Participant)

At the start of the project, participants were asked to rate their engagement in art-making activities, and their level of confidence in using art materials and discussing artworks. Ratings at the end of the project showed overall significant increases in all these domains, reflecting growth in confidence, meaningful connections, and enjoyment of the creative activities. Initially, 45% of participants felt confident about discussing art, and 85% did so at the end of the project. Participants enthusiastically engaged in the end-of-project exhibitions and found these affirming of themselves and their artworks. Participants also recorded high levels of satisfaction with the project: 82% found the sessions “worthwhile and valuable” and 85% would recommend them to friends and family.

What Contribution did the Project make to Participants’ Emotional Wellbeing?

The project came at the right time as it gave me that calmness that I needed and doing the workshops, I found I was able to cope a lot calmer with everything I was doing. (Participant).

As a short-term intervention, the project cannot overclaim to have a lasting and meaningful impact on participants’ emotional wellbeing. Nevertheless, participating in a single session or a brief series of sessions can provide short-term relief and improve feelings and moods (Hecht et al., 2023). This can have a meaningful impact on physical health, including reduction in stress hormones and increased emotional wellbeing (Visnola et al., 2010). Although there are no longitudinal data to establish how long these experiences lasted, positive ratings for these domains were high, reflecting a promising contribution.

What we Learned from the Pilot Project and Implications for Future Programs

Active, Innovative Outreach Supported Diversity and Inclusion

The curators’ innovative outreach work with FE colleges had several positive outcomes: It attracted ESOL participants, many of whom were migrants and refugees. The library setting offered them a bridge between their educational and creative needs as well as an opportunity to build links with their new communities. Their presence also contributed to libraries achieving their aim to be more diverse and inclusive. At a time when the UK discourse on migration, immigration, and refugees is often hostile, introducing the people behind the headlines to local communities can help lessen prejudice, even if this is to a small degree. This outreach approach will be replicated in future AMB projects.

Benefits of Pre-project Training and Art Therapy Skill-sharing

Staff reported feeling more confident and better equipped to meet potentially challenging situations, especially with the rise in mental health needs among library users.

There were some vulnerabilities within the participants, which needed to be managed with sensitivity. The pre-project training session was very helpful. (Curator)

The training also underpinned the reflexive and inclusive culture of the project. The art therapist introduced attachment and trauma theories linking life events and emotional development and how these experiences could affect someone’s ability to respond to others people and to stressful situation. It was also helpful to explore how art making can at times trigger some negative associations for participants and that consequently, some may react to this experience. The reflexive exploration of staff members’ own stories with art echoed this issue, as some shared their own challenges or their disconnection from art (see below). This deepened their understanding of participants’ processes and supported a less reactive stance to challenges from participants.

Building Reflexivity through Art-based Processing

During the pre-project training sessions, PiH curators, library staff, and art workers were invited to think about their journey and story with art using artmaking. Many found this helpful and impactful in their approach to work:

I’ve worked on lots of different projects, and I don’t think I have ever been asked to reflect on my own experience and journey, I found that really valuable, and it’s something I will take with me into this project and future ones. (Library staff).

This reflexive, art therapy-based approach was integrated into the co-curation sessions which laid the groundwork for the rest of the project and supported the work of the creative practitioners. The art therapist suggested that the curators could develop a reflexive visual diary during the project and make art-based responses from their experiences within the sessions. “Response art” is well integrated into current art therapy practice as a way of processing and learning from achievements, challenges, and supporting insight (Nash, 2020). This has a direct impact on the quality of the work:

I found this element very valuable and really important. This is what made the project unique, and it enhanced participants’ experiences. (Curator).

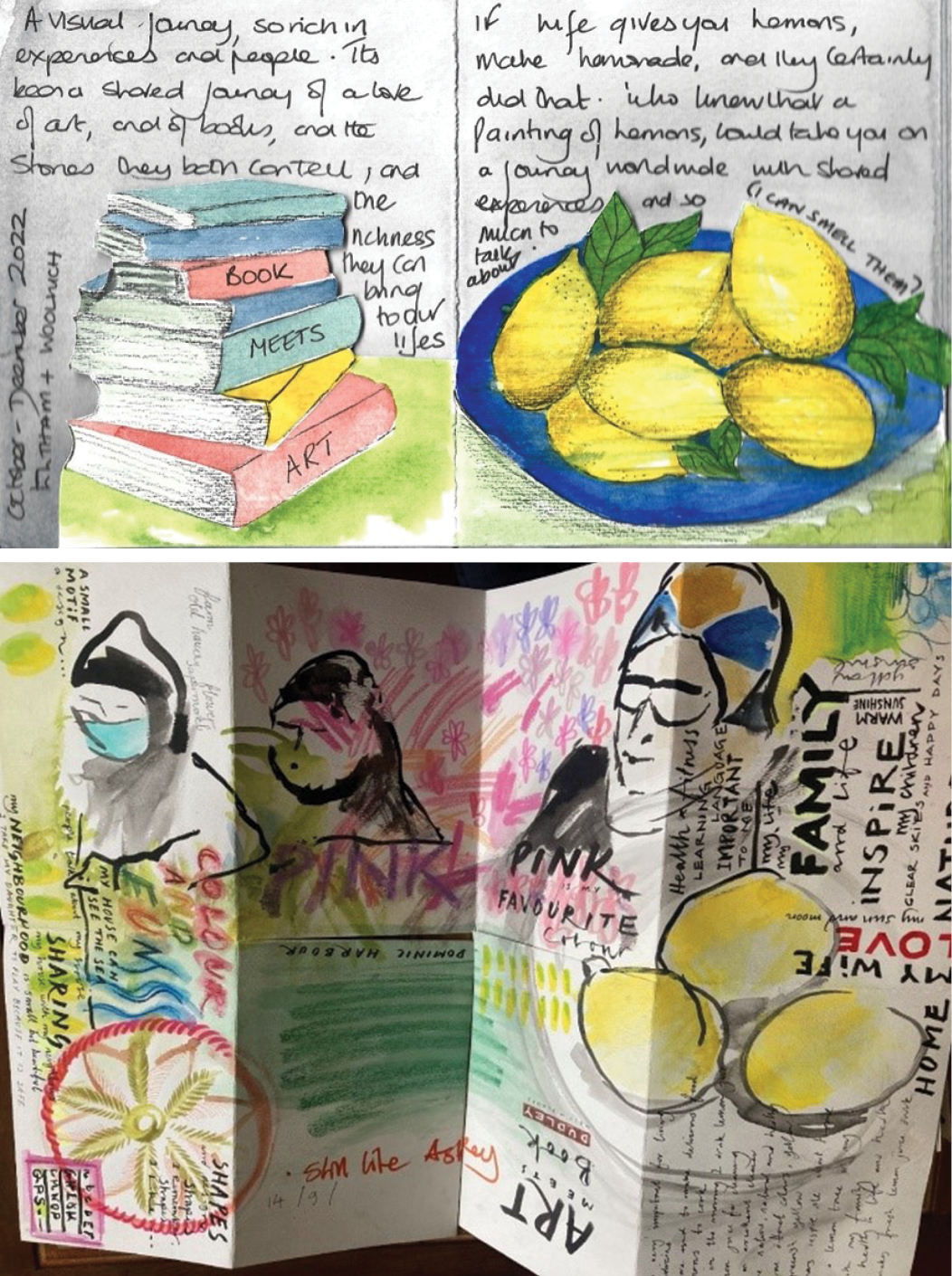

The curators included the selected artworks in their reflective visual diaries, as these sparked moving and creative discussions among participants about different perceptions, connections to personal experiences, and sharing of life stories. For instance, an artwork including lemons sparked reminiscence of countries of origin for ESOL participants who drew these in their artworks as did both curators (Figures 7 and 8).

FIGURE 7 | Participant’s art response with lemons.

FIGURE 8 | Curator’s reflective visual diary.

Although keeping a reflexive visual diary was not in the original brief, it underlined the importance of art-based processes and strengthened the identity of the project as art-led. It will be a useful tool to include in future projects.

Using a Co-production Approach for Curation Sessions

Co-production is a way of working that involves people who use health and care services, carers and communities in equal partnership; and which engages groups of people at the earliest stages of service design, development and evaluation. (NHS England, 2024).

The PiH artworks provided the basis for participants’ creative exploration, and the selection process was pivotal in building an inclusive and enabling culture. The curators adopted a co-production approach to ensure participants were fully consulted and engaged in this process and that lack of formal art knowledge was not experienced as a barrier. Providing two co-curation sessions ensured there was enough time for these conversations and that participants did not feel rushed, particularly when they were not confident with their spoken English.

The co [production]-curatorial process was to fire up as much potential around the artworks and to introduce a sense of ownership and choice, being sensitive, being open, being democratic but questioning and give everyone a chance to respond to artworks. (Curator)

The artworks were really central as the base of the project and a great base for a creative start. (…) The process was unusually careful and done in-depth, it could have been a snap decision. Those conversations with participants gave a great base and they already had opinions and much more considered responses and allowed for some lovely work. (Artist).

The curators’ approach enabled participants to develop a language and find a voice to engage with artworks. The co-production approach also relied on sharing their knowledge about the artworks, the artists’ stories, and the context in which they worked. The acquisition of knowledge is essential to increasing feelings of engagement in and enjoyment of art-viewing (Lachapelle et al., 2003), and this was reflected in participants’ high satisfaction ratings.

The Changing Role of Libraries

The library settings were pivotal in engaging people who do not usually connect with art and creative activities. As free community-based settings, libraries were seen as accessible and “safe” resources, especially by participants who were migrants and refugees, and valued the connection to learning and education. Post-project reflexive sessions underlined the important part played by library staff who were very supportive and helpful. However, staff numbers have been cut over the past few years, at a time when library activities have increased considerably and when the profiles of library users have changed:

We are being approached by partners to help them reach families and the vulnerable with specific support around warmer homes initiatives, mental health support (…) (Libraries Connected, 2022)

This indicates a need for basic training in mental health and therapeutic skills for all project workers, including library staff when working with a client group who may experience mental health problems more frequently. Co-working sessions with colleagues will also be essential in ensuring the future safe delivery of the project. Holding in mind the workload pressure that library staff experience, planning for future projects will need to be co-produced with them to ensure that it is not experienced as another source of stress but as a stimulating and enjoyable experience.

Concluding Reflections

The AMB library setting is key in reaching people who do not usually engage in art. AMB also integrates the skills and experience of professionals from different backgrounds. Projects built on cross-professional collaboration benefit from sharing diverse viewpoints, which often enriches the quality of participants’ experiences (Betts & Huet, 2002). Of particular significance was the curators’ active outreach initiative with FE colleges, which led to many ESOL students joining the project. The co-production ethos was also central in engaging all participants and supporting them to build more confidence in art.

At times of economic hardship, the arts are often seen as a disposable luxury, an indulgence. Yet their relational quality (Bourriaud, 2001) offers a bridge between individuals and communities where our need for joyfulness, connection, and belonging can be met and nurtured.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful for the support of the Paintings in Hospitals team, including Sandra Bruce-Gordon (chief executive at the time of the project), Dominic Harbour and Janet Bates (curators), and the artists and library staff who are pivotal to the success of the AMB project.

About the Author

Val Huet, PhD, visiting professor at School of Creative Arts, University of Hertfordshire, commissioned researcher and co-director of the Oxford College for Arts & Therapies.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: v.huet@herts.ac.uk; X (Twitter) handle: @Valhuet1; ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7390-0291.

Conflict of Interest

The author was funded by Paintings in Hospitals as an independent trainer and researcher for this project. She is familiar with the role of practitioner/researcher and, as a Health and Care Professions Council–registered art therapist, understands the importance of gathering and analyzing data ethically and impartially.

References

Betts, D., & Huet, V. (Eds.). (2022). Bridging the creative arts therapies and arts in health. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Bourriaud, N. (2001). Relational aesthetics. Les presses du réel.

Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport. (2020). Museums – Taking part survey 2019/20. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/taking-part-201920-museums/museums-taking-part-survey-201920#:~:text=In%202019%2F20%2C%20the%20most,75%20and%20older%20(36%25).

Fancourt, D., & Finn, S. (2019). What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

Hecht, C. A., Gosling, S. D., Bryan, C. J., Jamieson, J. P., Murray, J. S., & Yeager, D. S. (2023). When do the effects of single-session interventions persist? Testing the mindset + supportive context hypothesis in a longitudinal randomized trial. JCPP Advances, 3(4), e12191. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcv2.12191.

Huet, V. (2012). Creativity in a cold climate: Art therapy-based organisational consultancy within public healthcare. International Journal of Art Therapy, 17(1), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2011.653649.

Knifton, L., & Inglis, G. (2020). Poverty and mental health: Policy, practice and research implications. BJPsych Bulletin, 44(5), 193–196. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2020.78.

Lachapelle, R., Murray, D., & Neim, S. (2003). Aesthetic understanding as informed experience: The role of knowledge in our art viewing experiences. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 37(3), 78–98. https://doi.org/10.2307/3527305.

Libraries Connected. (2022). Libraries and the cost of living crisis. Retrieved from https://www.librariesconnected.org.uk/sites/default/files/cost%20of%20living%20crisis%20briefing%20note%20final.pdf.

Nash, G. (2020). Response art in art therapy practice and research with a focus on reflect piece imagery. International Journal of Art Therapy, 25(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2019.1697307.

NHS England. (2024). Co-production using the Always Events® quality improvement methodology. Retrieved from https://www.england.nhs.uk/always-events/co-production/.

Parenta. (2019). Reflective practice vs reflexive practice. Retrieved from https://www.parenta.com/2019/05/01/reflective-practice-vs-reflexive-practice/.

Paintings in Hospitals. (2024). Our mission. Retrieved from https://www.paintingsinhospitals.org.uk/our-mission.

Upton-Hansen, C., Kolbe, K., & Savage, M. (2021). An institutional politics of place: Rethinking the critical function of art in times of growing inequality. Cultural Sociology, 15(2), 171–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975520964357.

Visnola, D., Sprūdža, D., Baķe, M. Ā., & Piķe, A. (2010). Effects of art therapy on stress and anxiety of employees. In Proceedings of the Latvian Academy of Sciences. Section B. Natural, Exact, and Applied Sciences (Vol. 64, pp. 85–91).

1 An evaluation findings report was submitted to NESTA