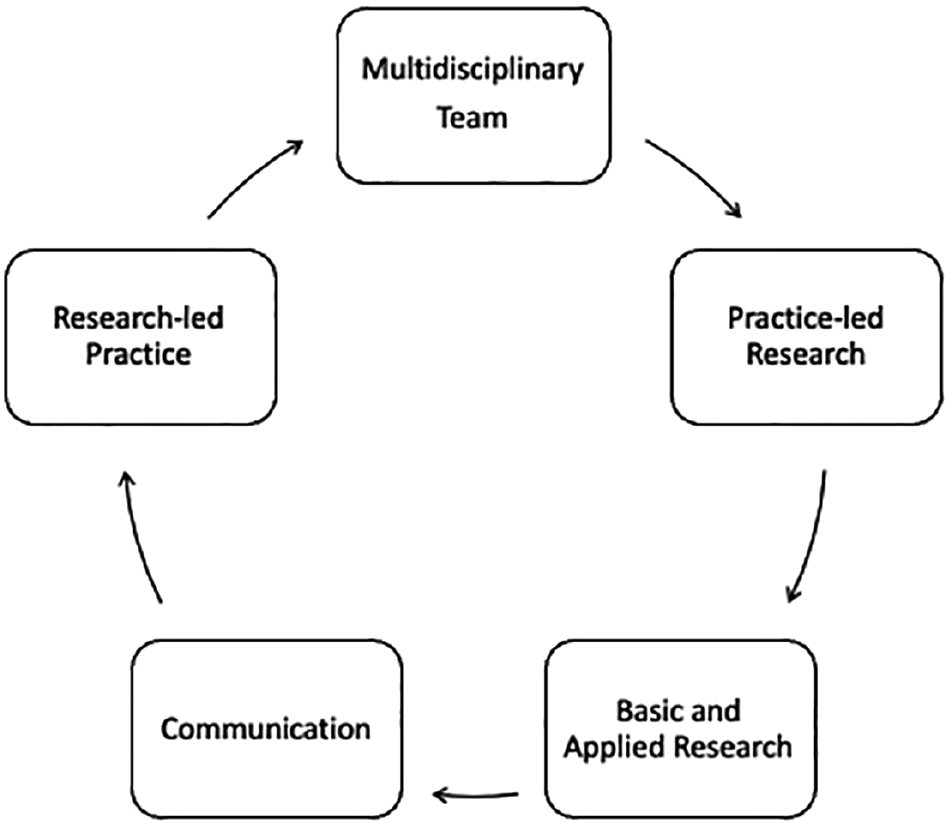

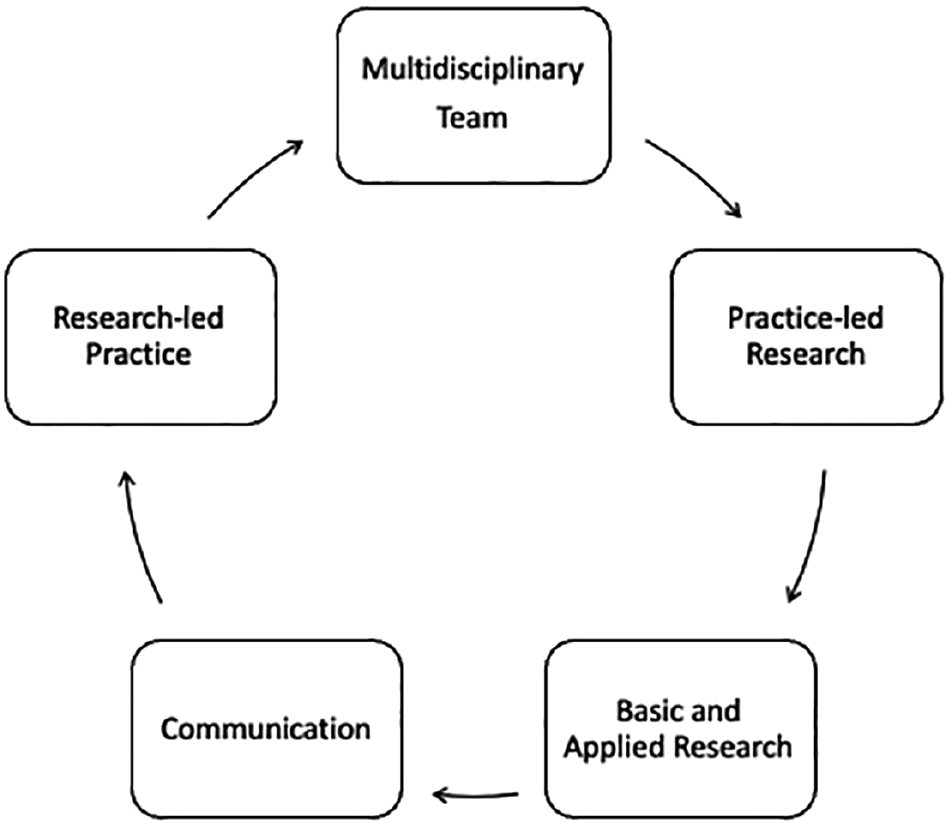

FIGURE 1 | Practice-research-practice cycle. Adapted from McKechnie and Stevens (2009).

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2024) 10(2):235–252 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2024/10/19 |

Cultivating Well-being, Community Cohesion, and Sense of Purpose through African Contemplative Practices

通过非洲冥想实践培养幸福、社区凝聚力和目标感

1University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

2Sibikwa Arts Centre, South Africa

Abstract

Exploring Southern African contemplative traditions addresses an important gap in the fields of contemplative science and healing modalities. In contrast to meditation practices drawn from Eastern wisdom traditions, practices embedded in African spirituality are sound- and movement-based and conducted in community settings. During a research retreat in South Africa, attended by traditional healers, creative arts therapists and performers, mindfulness and neuroscience researchers, and a Buddhist monk, indigenous rituals were performed by experienced facilitators and analyzed through group reflection sessions. Phenomenological data were recorded and coded. Participants identified how the synchronized movements, vocalization, and multisensory listening enabled experiences of self-transcendence, connection, and social cohesion, eliciting emotions of peacefulness, harmony, and joy. Using thematic analysis, four recurring threads emerged: sacred sense of purpose, nervous system self-regulation and co-regulation, enhancement of pro-social qualities, and community cohesion. These findings are presented to support international dialog and illuminate relationships among Eastern, Western, and African wisdom traditions. The global decline in mental health provides increased relevance, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and the impact of perpetuated historical injustices that have rendered individuals and communities isolated and disconnected. This article proposes that embodied rituals and arts-based therapies, alongside mindfulness practices, could provide effective ways to enhance personal well-being and build community cohesion.

Keywords: African psychology, wisdom traditions, contemplative practices, embodiment, healing, community cohesion, sense of purpose, relational ontology

摘要

本文通过探索南非冥想传统填补了冥想科学与疗愈方式领域中的一个重要空白。与源自东方智慧传统的冥想实践不同, 根植于非洲灵性中的实践以声音和动作为基础, 并且通常在社区环境中进行。在一次南非的研究静修活动中, 传统治疗师、创造性艺术治疗师、表演者、正念和神经科研人员以及一位佛教僧侣参加了其中。在经验丰富的引导者的带领下, 团体进行了一些本土仪式, 并通过小组反思环节进行了分析。现象学数据被记录并进行了编码。参与者发现了如何通过同步的动作、发声和多感官听觉体验促进了自我超越、连接和社会凝聚感的产生, 并激发了平静、和谐与喜悦的情感。通过主题分析, 发现了四个反复出现的核心要素:神圣的目标感、神经系统自我调节与共同调节、促进社会性品质的提升和社区凝聚力。这些发现旨在支持全球对话, 并揭示东方、西方和非洲智慧传统之间的关系。全球心理健康的下降使得这一问题的相关性更加突出, 尤其是受新冠疫情和历史上持续的不公正影响, 造成了个体和社区的孤立与断裂。本文提出, 具身化仪式和基于艺术的治疗, 以及正念实践, 可能为提升个人幸福和促进社区凝聚力提供有效的途径。

关键词: 非洲心理学, 智慧传统, 冥想实践, 具身化, 疗愈, 社区凝聚力, 目标感, 关系本体

Introduction

Contemplative practices have formed part of religious, philosophical, and humanistic traditions across all cultures since ancient times. Two key intentions of contemplative practices are to cultivate awareness and communion/connection to God, the Divine, or inner wisdom (Contemplative Mind, 2021). Although secular mindfulness practices have focused on cultivating self-awareness, both Buddhist and mystical Christian traditions focus on transcendence of the self to connect with the divine oneness of Buddha nature or a divine God, respectively (Trammel, 2017). The self in relationship with others and the divine is an integral aspect of African wisdom traditions.

Davidson and Dahl (2017, p. 121) defined contemplative practices as forms of mental training to elicit “self-awareness, self-regulation, and/or self-inquiry to enact a process of psychological transformation” with the aim to “bring about a state of enduring well-being or inner flourishing.” By investigating African contemplative practices, which are rooted in the relational philosophy of ubuntu, we believe we can open the field of contemplative science to a cultural category of spiritual practices that has received limited attention to date. Here we focus predominantly on practices from the Southern African context.

The research retreat from which this article emerges was supported by a think tank grant from the Mind & Life Institute, established in 1991, seeking to explore the question of “what impact could be achieved through combining scientific inquiry with the transformative power of contemplative wisdom” (Mind & Life Institute, 2020). In recent years, the institute has “started looking deeply at how to advance the principles of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) within [their] organizational structure, processes, and programs” (ibid., 2020). Mind & Life think tanks invite transdisciplinary participation and multiple epistemologies to open new fields of enquiry, and this research retreat provided the opportunity to continue the discussions that began at the 2017 Mind & Life Dialogue held in Botswana.

The aim of this article was to identify and analyze the experience of participating in selected indigenous rituals and cultural practices from the South African context. Research participants were invited to reflect on their temporary state changes during the guided practices, within a retreat context, while the facilitators reflected on their own experience of longer-term changes resulting from their engagement in these rituals.

Conceptual Framework

Indigenous, precolonial cultures each have distinct practices for individual health, community cohesion, and connection with the natural world. They tend to rely on embodied rituals and oral ways of transferring this wisdom from generation to generation.

Africa’s embodied arts-based healing practices are community-based and require participation, both essential aspects of the African philosophy of ubuntu (Edwards, 2011; Edwards et al., 2009; Mutwa, 1996). With ongoing psychology-based studies and a commitment to neuroscience research, we could establish how these practices, which we define as contemplative, could promote social cohesion and support resilience and aid collective human flourishing, particularly given the dehumanization of the colonial and apartheid eras.

Although there has been some research on relational practices (Kok & Singer, 2017) and movement practices (McGonigal, 2019; Schmalzl & Kerr, 2016), most of the secular mindfulness and Buddhist meditation practices that have been the object of research are conducted in silence, stillness, and solitude. Empirical research studies (both qualitative and quantitative) have revealed significant benefits of these meditation practices (Davis & Hayes, 2011), namely, affective benefits, such as emotion regulation (Carmody, 2009) and increased flexibility (Farb et al., 2010; Hawley et al., 2014); intrapersonal benefits (Siegel, 2007), including self-awareness (Lutz et al., 2016), morality (Sevinc & Lazar, 2019), and fear modulation (Brown et al., 2012); and interpersonal benefits, such as pro-sociality (Weng et al., 2013; Zaki & Ochsner, 2012) and relationship satisfaction (Carson et al., 2006). Tang et al. (2016) describes how:

Growing evidence has indicated that mindfulness practice induces both state and trait changes: that is, it temporarily changes the condition of the brain and the corresponding pattern of activity or connectivity (state change), and it also alters personality traits following a longer period of practice. (p. 29)

In a meta-analysis of mindfulness, loving-kindness, and compassion meditation practices, Donald et al. (2019) found an association between meditation practice and altruism. Of interest was that mindfulness alone (with its focus on nonjudgmental awareness) predicted prosocial helping behaviors even without including loving-kindness and compassion practices. The researchers identified that greater empathic concern, emotion regulation, and positive affect were key to enhancing pro-social behaviors. Also relevant for this article was their conclusion that intergroup bias was reduced immediately following a mindfulness meditation, suggesting that “mindfulness fosters ethical and cooperative behavior across a range of interpersonal contexts” (Donald et al., 2019, p. 119).

Some mindfulness facilitators have raised a concern that silent sitting practices do not always give beneficial results for participants with a history of trauma (Treleaven, 2018). Rhythmic movement practices, however, have been shown to release trauma held in the body (van der Kolk, 1994) and could therefore be an important prerequisite for, or alternative to, sitting practices. Arts-based therapies and indigenous contemplative traditions show promising results, as they are movement-based and conducted in community settings (Makanya, 2014). Kok et al. (2013) and Dana (2018), extending the work of Porges (2007), have theorized that the human nervous system is best regulated by social connection and social engagement. Synchronized movements (during dance or drumming) and vocalization have been shown to support experiences of connection and belonging (Bensimon et al., 2008). Empirical research has also revealed considerable health benefits of arts-based therapies, such as improved interoception and body awareness, concentration and focus, stress reduction, and the ability to relate to self and others with kindness, compassion and acceptance (Stuckey & Nobel, 2010).

With the high incidence of mental health and other social disorders worldwide, exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic (World Health Organization, 2019), the need to find ways of working skillfully with body-mind connections necessitates deeper exploration. Ancient cultural practices may well hold the key to supporting resilience, enhancing human well-being, and flourishing in these times of global mental health crisis. Although they may not have been tested yet in clinical trials,

metaphysics are heuristic frameworks, derived partly from experience, partly from intuition, tested, nuanced, and course-corrected with practice and validation in individual and collective experience. (Banerji, 2018, p. 9)

We selected five contemplative healing practices that are commonly performed within the Southern African context: umphahlo, umgidi wokulingisa, isicathamiya, iintsomi, and djembe drumming. These are described in greater detail by Draper–Clarke and Green (2023) and shown in video format in Draper-Clarke (2021).

Umphahlo uses instruments, song, and herbs (mpepu/sage and snuff) to invite and welcome the ancestors (the living dead) into the space to seek their wisdom. They are called with head bowed to show humility, and healers make it clear that they are ready to listen at a multisensory level to the messages of the living dead.

Umgidi wokulingisa has been translated as a stamping ritual, which in traditional contexts leads to an altered state of consciousness or trance to remove the usual barriers between the living and the living dead. Framed within a drama therapy context, it has been used to bring the energy of loved ones into the circle, enabling deep healing and connection (Seleme, 2017).

Isicathamiya is a type of cappella developed by migrant Zulu communities combining singing (often call and response) and dance. It enables an embodied understanding of the history of South Africa, particularly of mine workers living in hostels.

Iintsomi is part of the oral tradition rooted in Africa and is often translated as storytelling. However, it encompasses a sense of an invitation to participate in a storytelling moment. The participants are part of the story, and while there is a formal structure, it is the energy of the participants that builds the story. Many iintsomi moments do not have a clear conclusion but rather are left open-ended to encourage reflection (Busika, 2015). This oral tradition has been a way of transferring African cosmology to children and the community for generations.

Djembe drumming is carried out with a sense of moving into conversation and enabling the drummer’s intention and words to be transmitted through the vibrationnonbrspaceof the drum. This allows for a conversation to be held between the drum and the drummer as well as within the whole drum circle community. The word ngoma has a meaning similar to vibration or resonance, which allows the transmission and receiving of messages. The word is also used for the skin of the drum, which callsnonbrspacepeople to it, as well as a type of dance or a nighttime dance ceremony. It is the root of the word sangoma or healer, someone who can receive messages from the ancestors.

Methods

The research design was approved by the Ethics Committee at the University of the Witwatersrand and guided by McKechnie and Stevens’ practice-research-practice cycle (Figure 1).

The thirteen participants (Table 1) comprised two traditional healers, two arts therapists, two applied theater practitioners, a neuroscience researcher, a Buddhist monk, a group facilitator, a videographer, and three researchers trained in mindfulness and arts-based research. The choice of facilitators was purposive and pragmatic, based on their experience both in traditional practices and in contextualizing them for a diverse, international audience. They also had a preexisting relationship of trust with the research team through their association with the Drama for Life department.

One of the traditional healers is both an herbalist and a wisdom keeper (sanusi) and has studied several religious traditions (Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism) as well as heeding his calling as an African healer. The other traditional healer is known as “the digital sangoma,” as she has a global audience through her YouTube channel. The facilitators of umgidi wokulingisa and iintsomi are trained drama therapists, so they are also able to adapt these traditional practices for participants from diverse religious and spiritual backgrounds. The applied arts and theater practitioners of isicathamiya and djembe drumming have also worked in multicultural contexts and are able to describe and interpret the practices to identify their key components.

FIGURE 1 | Practice-research-practice cycle. Adapted from McKechnie and Stevens (2009).

TABLE 1 | Participant Demographics

| P | Identity | Age (years) | Sex | Spiritual tradition | Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Traditional healer (sangoma) | 31 | Female | African | Northern Sotho |

| 2 | Traditional healer (herbalist), indigenous knowledge systems practitioner | 28 | Male | iSintu | isiXhosa |

| 2 | Traditional healer (sangoma) | 31 | Female | African | Northern Sotho |

| 3 | Drama therapist and traditional healer initiate | 31 | Trans Female | African | isiZulu |

| 4 | Drama therapist and academic | 35 | Female | Christian | isiXhosa |

| 5 | Composer and creative director | 41 | Male | None | isiZulu |

| 6 | Performing artist | 33 | Male | Christian | Southern Sotho |

| 7 | PhD candidate in neuroscience | 47 | Female | Spiritual | English |

| 8 | Culture officer | 40 | Male | Buddhist | Tibetan |

| 9 | Academic, theater director, and drama therapist | 53 | Male | Interfaith | English |

| 10 | Facilitator, trainer, and researcher | 51 | Female | Buddhist | English |

| 11 | Arts and culture manager | 32 | Female | Christian | English |

| 12 | Trainee arts therapist | 35 | Female | Shamanism | English |

| 13 | Videographer | 28 | Male | Christian | Sepedi |

Seven participants identified as Black African, one as African, one as Asian, one as colored, one as South African Jewish, and two as White/Caucasian. One participant identified as transgender, one as queer, ten as cisgender, and one preferred not to answer.

As African indigenous contemplative practices have been impacted by imperialism and colonialism, we were also informed by the transformative paradigm (Kara, 2015; Mertens, 2007), which foregrounds the need for social justice. Considering Fletcher's (2017, p. 4) cautions that “ontology is not always reducible to epistemology,” we inquired into the most effective ways of creating knowledge and designed the retreat as a performative and experiential learning journey. In line with both Eastern and African ways of knowing that Robinson–Morris (2018) describes as being-becoming, we chose a phenomenological approach, as “lived experience is where we start from and where all must link back to, like a guiding thread” (Varela, 1996, p. 334).

Aligned with the relational and communal philosophy of ubuntu, each participant was invited to contribute to meaning making through critical reflective practice (Fook & Askeland, 2007) during a 30-minute feedback session at the end of each ritual. We wanted to understand participants’ state changes after each performance ritual and asked the participants about their kinesthetic, emotional and spiritual experiences (Hartelius & Ferrer, 2013). The three researchers rotated roles for each practice: two as participant observers, able to sense into the effects of the practices and make meaning at a personal level, and one as an external observer, watching the impact of the practices on the other participants and taking field notes. This addressed the double hermeneutic of phenomenology, where “the participants are trying to make sense of their world; the researcher is trying to make sense of the participants trying to make sense of their world” (Smith, 2007, p. 53).

The practice and feedback sessions were documented using field notes and recorded, both with audio and video equipment. The transcribed reflection sessions provided the primary data set for this article. Thematic analysis as “a method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data” (Braun & Clarke, 2012, p. 6) was then used to reveal “experiences, meanings and the reality of participants” (ibid., p. 9) across each of the different practices. The analysis followed the six phases of thematic analysis, namely familiarization of data, generation of codes, combining codes into themes, reviewing themes, determining the significance of themes, and reporting of the findings.

The questions in the reflection sessions were open-ended, inviting responses based on a felt sense (Gendlin, 1991). The questions included the following: What did you experience during the session? What momentary changes did you experience (state changes)? Have you experienced longer-term changes as a facilitator of this practice?

Results

Subjective experiences were identified for each ritual. Verbatim responses from the subjects’ perspective (Sandelowski, 2010) are reported to illustrate their experiences. The transcribed data sets were coded, and we present this table of codes and emergent themes (Table 2) to interpret the data across each ritual practice and to contextualize it within the field of contemplative science.

TABLE 2 | Data Coding and Emergent Themes

| Codes | Themes |

|---|---|

| Sense of purpose and guidance Awe and wonder Understand own nobility/own cultural heritage Revitalizing cultural practices Interdependence and interconnectedness (human/nonhuman) Connection with spirit (ancestors/nature) |

Sacred sense of purpose |

| Sense of safety Rehumanization Calmness and peacefulness Release of traumatic energy/embodied trauma Overcoming trauma Emotion regulation/stress reduction Healing Body-based integration Powerful silence |

Nervous system regulation |

| Empathy and compassion Deep listening Present moment awareness Joyfulness Humility Experience of self-transcendence Regulated attention Playfulness and childlike curiosity Creativity and problem-solving |

Pro-social qualities |

| Attunement and entrainment Harmony and unity in diversity Cross-cultural understanding Reduction of in/out group bias Overcoming oppression Community connection Resilience and agency Interdependence and interconnectedness |

Community cohesion |

Umphahlo

The traditional healer (1) described the changes that took place within her once she had accepted her calling. Before, she said, “I had no control of myself—my thoughts and words,” but afterwards, she noticed she could manage her energy better, becoming “more balanced and still.” When she attended to her spiritual practice, “the world slowed down and became so much more peaceful.” Even in her schoolwork, she had previously described herself as “dyslexic and dumb in academics,” but afterwards, she felt like, “a born genius” and achieved high grades.

The traditional healer (2) also recounted how wild he was before accepting his calling and how he searched in different traditions until “My ancestors kept poking me, saying ‘you need to come home.’” He demonstrated the phahla practice, inviting the group to join in the singing, creating a visceral sense of the sacred. Both healers later spoke to the state of self-transcendence that is achieved through this practice so that they can sense the energy of clients and offer healing rituals and insights.

Both healers confirmed that they have felt a deep sense of sacred purpose (ubizo) since accepting their calling, which contributed greatly to their psychological well-being.

The codes emerging from the transcribed reflection sessions on umphahlo included sense of purpose and guidance, humility, emotion regulation, deep listening, present moment awareness, understanding one’s cultural heritage, revitalizing cultural practices, connection with spirit (ancestors/nature), experience of self-transcendence, and interdependence/interconnectedness.

Umgidi Wokulingisa

After the drama therapist (3) offered the umgidi practice, several participants noted enhanced capacities for empathy and compassion. One participant expressed the healing potential of the practice:

the whole country is traumatized, it needs counseling…this session today, the gift you have given, I thought, I want my family to attend this session.

In discussing changes that the facilitator had noticed in creating this practice, she said, “I tend to be particularly in my head and think a lot, and when I connected with this practice, it allowed me to let go, and just be.” She also spoke to the experiences of her African clients, who had been able to access symbols from their unconscious with positive effect. She questioned what would emerge in sharing this practice with other cultures. The neuroscientist responded, “There are three different white cultures here to confirm that this process works perfectly.” She expanded, from a neuroscience perspective, explaining,

You are not just accessing the limbic system but have gone much deeper…As soon as you engage movement and engage the spine, you are engaging the whole brain…We engaged with our primitive brain and all the way up…While I was having my experience, I was also able to analyze the experience, and I was reasoning while accessing. We all accessed love, and love is in the substantia nigra and the ventral striatum…which is activated with compassion. We were accessing language and deep personal stuff, which is cross cultural…You are accessing brain-body integration, and we can only integrate through the body. That’s where this power is, and your setting up allowed us to have emotional experiences while still analyzing them.

Drawing from the transcription of both the practice and the reflection session, the following codes were identified: sense of safety, rehumanization, healing, empathy and compassion, joyfulness, playfulness and childlike curiosity, harmony and unity in diversity, resilience and agency, interdependence and interconnectedness, and revitalizing cultural practices.

Isicathamiya

The creative director (5) presented a story of his life growing up during the violent end of apartheid and guided the group through a dance enactment, offering an embodied experience of life “deep in the shaft, digging for gold.” Songs are not just songs; they are a story or information or problem solving. The rhythm of the song and movement helped work teams lift heavy objects. “If you use the wrong leg, you’ll kill someone, it’s going to fall and chop his leg off.” During the personal retelling of history and the presentation of isicathamiya, participants were visibly shocked, experiencing a visceral sense of the horror of the time.

In the reflection session, the neuroscientist advised that, given the facilitator’s childhood experiences, it was no surprise that he had failed his high school leaving exam, as the brain’s working memory is impaired by trauma. In ensemble practices, such as isicathamiya, stamping allows trauma to be released from the body, and singing creates a sense of solidarity. The call and response also enable a transcendence from the mind’s turmoil. The group reflected that sharing these embodied practices with school communities could also heal trauma-impacted minds and help young people achieve their potential.

One participant commented that while compassion is innate, healing needs to happen to let compassion resurface. Integration requires containment of ambivalence, of self, safety, emotion, and loss. The group also shared that healing could be considered a contemporary form of activism: “To heal, we needed to heal ourselves within our community.” It is within the collective that we can co-regulate.

During analysis of the performance and reflection sessions, the researchers identified the following codes: overcoming trauma, stress reduction, healing, body-based integration, creativity and problem solving, attunement and entrainment, overcoming oppression, community connection, resilience, and agency.

Iintsomi

The iintsomi stories, games, and praise poem presented by the drama therapist (4) revealed that not only children benefit from this modality. The performative session elicited deep connection, great joy, and delight in all participants. A return to the childlike experience of play energized everyone, offering “a way to tap into the source of life.” This allowed a distancing from an ego-centric perspective and a deepening sense of belonging.

After the iintsomi process, the group reflected using movement, poetry, and sounds. One participant demonstrated, and then explained, “When I feel childlike, light-hearted and joyful, I just want to cartwheel,” followed by another saying, “I am grateful for seeing how quickly my body responded to real play. My middle-aged body has not forsaken me; it was just simply waiting for me to move.”

In closing, the reflection session facilitator thanked the drama therapist for “making us remember the incredible joy, power, rejuvenation and restorative power of play, and that play can hold such deep and profound human experiences.”

This experience of iintsomi storytelling revealed its broader applications when facilitated as a dialogical approach for well-being, allowing participants to build internal strength, creativity and problem solving, and awareness of the environment and community. Additional codes that emerged included rehumanization, collaboration, and empathetic listening, awakening of agency and resilience, body-based integration, joyfulness, playfulness and childlike curiosity.

Djembe Drumming

The performing artist (6) led the drum circle, in the hall to start with and then outside at the fire where the group experienced a deepening sense of connection and social cohesion. In a significant moment, when the drum circle was disrupted by an unexpected visitor, the group held a powerful silence that de-escalated the incident immediately, allowing a sense of integration and a swift return to peace.

The codes identified during the reflection session were connection with spirit, sense of safety, powerful silence, deep listening, present moment awareness, joyfulness, experience of self-transcendence, attunement and entrainment, and community connection.

Emergent Themes

By analyzing each of the sessions and the final reflection session, four central themes were identified from the codes, linking the findings from these practices to findings within contemplative research, and these were sacred sense of purpose, nervous system regulation, pro-social qualities, and community cohesion (see Table 2). These are discussed below in reference to the literature to illuminate the potential contribution of these African rituals to the broader field of contemplative science.

Discussion

The holistic, embodied nature of these arts-based practices makes reductive research difficult and limits the generalizability of these findings to broader populations and settings. Indeed, attending a retreat can, in and of itself, contribute to a sense of well-being. Nevertheless, participants agreed that the rituals themselves had offered significant contributions to both their personal and collective sense of well-being, community cohesion, and sense of purpose and could open the way for on-going research studies. Well-being includes both individual nervous system regulation and cultivation of the pro-social qualities that lead to community cohesion, and many of these cultural practices have served this purpose to past generations.

Sacred Sense of Purpose

The healers described how their immersion within African wisdom traditions, and in service of their community, provided a sacred sense of purpose and meaning in their lives. In psychology and contemplative research, this has been reported as “one of the most robust predictors of psychological well-being” (Dahl & Davison, 2019, p. 62). The traditional healer (2) spoke to this saying,

enlightenment, in the African understanding, is not the goal. Once you get more enlightened, you have to go and do your work. This is why we cultivate practice, which involves healing people, communities and nations.

His observation bore a strong resemblance to the compassionate intention of Mahayana Buddhism, where practitioners promise to become enlightened for the sake of all, vowing “beings are numberless, I vow to save them all” (Chodron, 2007).

According to Edwards et al. (2009), the spiritual connection and knowledge of amadlozi provides security for an individual’s identity, which offers a sense of purpose and belonging within their culture. The connection with one’s ancestors places individuals within a deep sense of familial continuity, connection, and purpose, mitigating experiences of meaninglessness and social isolation that are growing public health concerns, particularly in the West (Lindsay et al., 2019).

The sense of purpose was also reflected at a communal level. The group noted that creative arts therapies, such as drama therapy, dance and movement therapy, art therapy and music therapy, provide a promising home for the re-emergence of these wisdom traditions. Movement practices such as umgidi wokulingisa and isicathamiya can effectively be framed as drama therapy or dance and movement therapy processes, offering multiple healing benefits. These interventions are held as group processes, which allow participants to heal in the community, an integral aspect of ubuntu. Participants with an African worldview can feel embedded in these cultural resources that have been passed from one generation to another. Participants from other cultures can also benefit from these experiential, relational and embodied ways of cultivating empathy and gaining insight. For those open to learning from different indigenous knowledge systems, these practices provide an embodied reverence for African relational practices that develop resilience and create cohesion and unity.

Nervous System Regulation

Research participants discussed their personal experiences of trauma-related hyper- and hypo-arousal, describing how prevalent this is within the Southern African context. They also noted that the movement-based practices allowed for nervous system regulation and an integration of trauma by returning to embodied awareness. Participants reported an increased capacity for regulating attention and heightening present-moment awareness, both of which have been shown to be key to trauma alleviation (van der Kolk, 1994).

The drama therapist’s (3) presentation revealed the potential of the umgidi process to allow for creative and flexible self-regulation in relationships and to address psychosocial challenges. Seleme uses this practice to assist clients in undoing ‘maladaptive cognitive patterns.’ It became clear how rituals provide healing for individuals within their community where illness is viewed as a fractured connection between the self and the collective (Baloyi & Mokobe–Rabothata, 2014; Makanya, 2014; Mutwa, 1996). Performing rituals to mark rites of passage is central to many African practices, offering a way to leave behind old roles and responsibilities and step into new ones appropriate to one’s age and position within society (Olupona, 1990). The use of ritual is just as relevant in terms of leaving behind maladaptive personal narratives to step into new ways of being and relating.

This use of sound- and movement-based practices, conducted in community settings, offers important access to cultivating self-awareness. By balancing the nervous system, particularly in situations of trauma, these African indigenous practices enabled a return to the silent contemplative practices taught in Eastern wisdom traditions in a way that could be described as trauma-sensitive (Treleaven, 2018).

Pro-social Qualities

The African healers spoke extensively of cultivating humility, a form of ego transcendence, during the process of supplication, umphahlo, as well as experiencing peacefulness and guidance in their daily lives. They described how their capacities for self-awareness, self-regulation, and self-transcendence have developed over time through their healing practices, corresponding to findings in Buddhist and secular mindfulness research (Haimerl & Valentine, 2001; Vago & David, 2012). It would be interesting to explore whether regular participation in these arts-based practices could develop trait qualities of attention, concentration, focus and presence, measured through functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans, in the way that mindfulness and compassion practices have been.

The practice of umphahlo allows for deep listening, creativity, and insight when requesting help from amadlozi to solve problems. This ability to find connection/communion with ancestors, a perceived higher power or divine presence, allowed for perspective taking and a movement away from a solid ego-centric focus, thus opening the capacity for different ideas to emerge.

On the final day of the research retreat, the sense of well-being in all participants was tangible, and there was a commitment to ongoing discussions around the potential for using these practices to overcome oppression and create opportunities for much-needed healing and, ultimately, human flourishing. In the closing circle, participants reflected on their experiences of harmony, joy, compassion, playfulness, and personal transformation.

Community Cohesion

Community cohesion was a dominant theme, reflecting the underpinning philosophy of ubuntu. The performative practices that required coordinated movement, namely, the isicathamiya call and response, the iintsomi games, and the drumming practice, allowed participants to attune with each other through multisensory listening. These arts-based movement practices elicited a shift into a mode of experiencing in which the cognitive structures of self/other and subject/object were no longer dominant. Instead, the group described a deepening sense of connection and interdependence.

Participants also spoke of a deepening of their own cultural and religious/spiritual identity within an environment of diversity. A metaphor offered by one facilitator was of a hand, each finger is unique, but all are needed, and it was referenced during the closing:

Each finger cannot be the same as the others; it needs to hold its own uniqueness for the community to be formed. Coming here, I asked questions of why am I here? The experience of a space of listening where people are willing to share parts of themselves and people are ready to receive. Wonderful things happen. A community happens. I take that from this experience in terms of how different the belief systems are yet at the same time we were able to meet in a most respectful way.

Not only did the community-held practices seem to strengthen healthy psychological qualities for each participating individual, but they also developed deepening levels of connection across ethnicity/race, gender identity, worldview, and culture within the research group. For example, using isicathamiya to explore the oppressive historical/political system of apartheid provided an embodied experience of the time, deepening levels of empathy and compassion for the suffering of the mineworkers. It also stimulated a discussion within the reflection session about the need for restorative justice.

Practices that support community cohesion align closely with the stated intentions of iintsomi practice, where the storyteller might craft a story to address difficulties arising within the community. The enacted art of storytelling allows for a felt sense of knowing, a shift in consciousness or a sense of understanding, or perceiving something that had previously eluded one’s grasp. Drumming circles have already been adapted widely to secular contexts, and there has been research into both physiological and psychological benefits. Placing drumming back within a context of healing and preventative healthcare, rather than performance, might allow the full benefits of ego transcendence to occur, enabling social cohesion. The work of Bloom (2005, in Núñez, 2016) asserts that while these ritual and ceremonial practices are multifaceted and based in the epistemology of a people, cross-cultural commonalities are definitely worth exploring.

While this article has not focused on humans’ relationship with the natural world, the sense of heightened connection with other living beings was experienced during a walk to the nearby waterfall. Masoga (2005) states that indigenous knowledge provides the basis for problem-solving strategies for communities: “they are life experiences which are organized and ordered into accumulated knowledge with the objective of their being utilized to enhance the quality of life and to create a liveable environment for both human and other forms of life” (p. 22).

Conclusion

In an article published after this retreat was held, Dahl and Davidson expressed the wish “to investigate the full range of contemplative practices” (2019, p. 60), particularly those that relate to pro-social qualities, cognitive insight, and life purpose, as well as those that reintroduce the sacred. The findings in this article offer a direct response to this call and may also help to address the WEIRD (Western/White, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic) problem (Henrich et al., 2010) that exists both in psychology (Masuda et al., 2020) and the mindfulness movement (Cash et al., 2021), where most research has been carried out with WEIRD participants.

Art-based therapies could offer a promising way of incorporating indigenous ceremonies and rituals into secular contexts. Both therapists and theater practitioners have the skills of critical reflexive praxis that are central to qualitative research (Saldaña, 1999). This commitment to reflexivity invites rigorous phenomenological research, ensuring that their applicability and effectiveness are constantly examined in the joint quests for healing and human flourishing. There is great scope to operationalize these modalities as group practices, where communities reflect in a social context and therefore access the co-regulating potential of social engagement (Dana, 2018). Critical reflexive praxis can contribute to the ongoing evolution of these epistemologies and the exploration of associated theories, allowing them to address contemporary health concerns, such as isolation, disconnection, and depression.

The paucity of studies available on the different practices also speaks to the need to conduct further qualitative research to deepen the global understanding of African relational ontology. Participants discussed how these fields have been undervalued due to the history of colonialism and apartheid. Healing past traumas that have taken place in Africa may best be served with practices that have evolved within this continent and are congruent with its worldview. Many of these practices find parallels in rituals and contemplative practices from other shamanic or indigenous communities, which knew what was required to release trauma from the interconnected body-mind. Given the recent recognition of global trauma, highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and social movements such as Black Lives Matter and #MeToo, we need a broad range of embodied contemplative practices to suit different events, personalities, and cultures. With ongoing research, the benefits of interactive arts-based contemplative practices and therapies can be understood within the context of the African philosophy of ubuntu. We offer these qualitative findings to contemplative/social neuroscience and arts-based therapy researchers globally to inspire and inform new directions in their own fields.

About the Authors

Lucy Draper-Clarke, PhD, is a retreat facilitator, mindfulness mentor, and researcher-practitioner in the field of mindfulness and compassion. After obtaining a doctorate in mindfulness and teacher education, she now offers public courses and conducts research at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. With a focus on compassionate activism, she works with those engaged in social transformation and healing to alleviate stress and increase resilience through awareness and compassion.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: lucyheartmind@gmail.com.

Caryn Green is the CEO of Sibikwa Arts Centre and a Culture Policy and Management PhD candidate at the University of the Witwatersrand. Her research interests are focused on collaborative, collective, and inclusive development, using relevant, responsive, and sustainable approaches to increase access, knowledge, and capacity for active agency, participatory governance, and culture-led democracy in local contexts.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of the Witwatersrand, protocol number H19/05/07. The participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Availability of Data and Materials

The qualitative datasets from this study are not publicly available due to confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This research was made possible by a Mind & Life Think Tank grant (2018).

References

Baloyi, L., & Makobe-Rabothata, M. (2014). The African conception of death: A cultural implication. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/iaccp_papers/119/.

Banerji, D. (2018). Introduction to the special topic section on integral yoga psychology: The challenge of multiple integrities. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 37(1), 27.

Bensimon, M., Amir, D., & Wolf, Y. (2008). Drumming through trauma: Music therapy with posttraumatic soldiers. Arts in Psychotherapy, 35(1), 34–48. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2007.09.002.

Bloom, M. V. (2005). Origins of healing: An evolutionary perspective of the healing process. Families, Systems, & Health, 23(3), 251.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. American Psychological Association.

Brown, K. W., Weinstein, N., & Creswell, J. D. (2012). Trait mindfulness modulates neuroendocrine and affective responses to social evaluative threat. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(12), 2037–2041.

Busika, N. F. (2015). A critical analysis of storytelling as a drama therapy approach among urban South African children, with particular reference to resilience building through Iintsomi: Iintsomi story method a dramatherapy approach [Master’s dissertation]. University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10539/19667.

Carmody, J. (2009). Evolving conceptions of mindfulness in clinical settings. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23, 270–280.

Carson, J. W., Carson, K. M., Gil, K. M., & Baucom, D. H. (2006). Mindfulness-based relationship enhancement (MBRE) in couples. In R. A. Baer (Ed.), Mindfulness-based treatment approaches: Clinician’s guide to evidence base and applications (pp. 309–331). Elsevier Academic Press, Cambridge, MA.

Cash, T. A., Gueci, N., & Pipe, T. (2021). Equitable mindfulness: A framework for transformative conversations in higher education. Building Healthy Academic Communities Journal, 5(1), 9–21. DOI: 10.18061/bhac.v5i1.7770.

Chodron, P. (2007). No time to lose: A timely guide to the way of the Bodhisattva. Shambhala Publications, Boston & London.

Contemplative Mind (2021). The tree of contemplative practices [illustration]. The Center for Contemplative Mind in Society. Retrieved from https://www.contemplativemind.org/practices/tree.

Dahl, C. J., & Davidson, R. J. (2019). Mindfulness and the contemplative life: Pathways to connection, insight, and purpose. Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 60–64. DOI: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.11.007.

Dana, D. (2018). The polyvagal theory in therapy: Engaging the rhythm of regulation. Norton series on interpersonal neurobiology. WW Norton & Company.

Davidson, R. J., & Dahl, C. J. (2017). Varieties of contemplative practice. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(2), 121–123. DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3469.

Davis, D. M., & Hayes, J. A. (2011). What are the benefits of mindfulness? A practice review of psychotherapy-related research. Psychotherapy, 48(2), 198–208. DOI: 10.1037/a0022062.

Donald, J. N., Sahdra, B. K., Van Zanden, B., Duineveld, J. J., Atkins, P. W., Marshall, S. L., & Ciarrochi, J. (2019). Does your mindfulness benefit others? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the link between mindfulness and prosocial behavior. British Journal of Psychology, 110(1), 101–125. DOI: 10.1111/bjop.12338.

Draper-Clarke, L. J. (2021). Creative research project: African contemplative practices for healing the past, transforming the present and for future flourishing. DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.14743437.

Draper-Clarke, L., & Green, C. (2023). African wisdom traditions and healing practices: Performing the embodied, contemplative, and group-based elements of African cosmology, orality, and arts modalities. Creative Arts in Education and Therapy, 9, 151–163.

Edwards, S. D. (2011). A psychology of indigenous healing in Southern Africa. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 21(3), 335–347. DOI: 10.1080/14330237.2011.10820466.

Edwards, S., Makunga, N., Thwala, J., & Mbele, B. (2009). The role of the ancestors in healing: Indigenous African healing practices. Indilinga African Journal of Indigenous Knowledge Systems, 8(1), 1–11.

Farb, N. A., Anderson, A. K., Mayberg, H., Bean, J., McKeon, D., & Segal, Z. V. (2010). Minding one’s emotions: Mindfulness training alters the neural expression of sadness. Emotion, 10(1), 25–33. DOI: 10.1037/a0017151.

Fletcher, A. (2017). Applying critical realism in qualitative research: Methodology meets method. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20, 181–194. DOI: 10.1080/13645579.2016.1144401.

Fook, J., & Askeland, G. A. (2007). Challenges of critical reflection: ‘Nothing ventured, nothing gained’. Social Work Education, 26(5), 520–533. DOI: 10.1080/02615470601118662.

Gendlin, E. T. (1991). On emotion in therapy. In J. D. Safran & L. S. Greenberg (Eds.), Emotion, psychotherapy, and change (pp. 255–279). The Guilford Press.

Haimerl, C. J., & Valentine, E. R. (2001). The effect of contemplative practice on intrapersonal, interpersonal, and transpersonal dimensions of the self-concept. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 33(1), 37–52.

Hartelius, G., & Ferrer, J. N. (2013). Transpersonal philosophy: The participatory turn. In H. L. Friedman & G. Hartelius (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of transpersonal psychology (pp. 187–202). Wiley Blackwell. DOI: 10.1002/9781118591277.ch10.

Hawley, L. L., Schwartz, D., Bieling, P. J., Irving, J., Corcoran, K., Farb, N. A., & Segal, Z. V. (2014). Mindfulness practice, rumination and clinical outcome in mindfulness-based treatment. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 38(1), 1–9. DOI: 10.1007/s10608-013-9586-4.

Henrich, J., Heine, S., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). Most people are not WEIRD. Nature, 466, 29. DOI: 10.1038/466029a.

Kara, H. (2015). Creative research methods in the social sciences: A practical guide. Bristol: Policy Press.

Kok, B. E., & Singer, T. (2017). Effects of contemplative dyads on engagement and perceived social connectedness over 9 months of mental training: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(2), 126–134. DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3360.

Kok, B. E., Coffey, K. A., Cohn, M. A., Catalino, L. I., Vacharkulksemsuk, T., Algoe, S. B., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). How positive emotions build physical health: Perceived positive social connections account for the upward spiral between positive emotions and vagal tone. Psychological Science, 24(7), 1123–1132. DOI: 10.1177/0956797612470827.

Lindsay, E. K., Young, S., Brown, K. W., Smyth, J. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2019). Mindfulness training reduces loneliness and increases social contact in a randomized controlled trial. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 116(9), 3488–3493. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1813588116.

Lutz, J., Brühl, A. B., Scheerer, H., Jäncke, L., & Herwig, U. (2016). Neural correlates of mindful self-awareness in mindfulness meditators and meditation-naïve subjects revisited. Biological Psychology, 119, 21–30.

Makanya, S. (2014). The missing links: A South African perspective on the theories of health in drama therapy. Arts in Psychotherapy, 41(3), 302–306. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2014.04.007.

Masoga, M. (2005). South African research in indigenous knowledge systems and challenges of change. Indilinga African Journal of Indigenous Knowledge Systems, 4(1), 15–30.

Masuda, T., Batdorj, B., & Senzaki, S. (2020). Culture and attention: Future directions to expand research beyond the geographical regions of WEIRD cultures. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1394. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01394.

McGonigal, K. (2019). The joy of movement: How exercise helps us find happiness, hope, connection, and courage. Penguin.

McKechnie, S., & Stevens, C. (2009). Knowledge unspoken: Contemporary dance and the cycle of practice-led research, basic and applied research, and research-led practice. In H. Smith & R. T. Dean (Eds.), Practice-led research, research-led practice in the creative arts (pp. 84–103). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Mertens, D. M. (2007). Transformative paradigm: Mixed methods and social justice. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(3), 212–225. DOI: 10.1177/1558689807302811.

Mind & Life Institute. (2020). About mind and life. Retrieved from https://www.mindandlife.org/about/.

Mutwa, V. C. (1996). Songs of the Stars: The lore of a zulu shaman. Barrytown: Station Hills Openings.

Núñez, S. (2016). Medicinal drumming: An ancient and modern day healing approach. NeuroQuantology, 14(2).

Olupona, J. (1990). Religion, law and order: State regulation of religious affairs. Social Compass, 37(1), 127–135.

Porges, S. W. (2007). The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 116–143. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.009.

Robinson-Morris, D. W. (2018). Ubuntu and Buddhism in higher education: An ontological (re) thinking. New York: Routledge. DOI: 10.4324/9781351067966.

Saldaña, J. (1999). Playwriting with data: Ethnographic performance texts. Youth Theatre Journal, 13(1), 60–71.

Sandelowski, M. (2010). What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in Nursing & Health, 33(1), 77–84.

Schmalzl, L., & Kerr, C. E. (2016). Neural mechanisms underlying movement-based embodied contemplative practices. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10, 169. DOI: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00169.

Seleme, B. (2017). Using umgidi wokulingisa (dramatic stamping ritual) within drama therapy to provide an accessible therapeutic space for cultural beings with an African worldview [Master’s dissertation]. University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/10539/25213.

Sevinc, G., & Lazar, S. W. (2019). How does mindfulness training improve moral cognition: A theoretical and experimental framework for the study of embodied ethics. Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 268–272.

Siegel, D. J. (2007). The mindful brain: Reflection and attunement in the cultivation of well-being. Norton series on interpersonal neurobiology. New York: WW Norton & Company.

Smith, J. A. (2007). Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods. Sage.

Stuckey, H. L., & Nobel, J. (2010). The connection between art, healing, and public health: A review of current literature. American Journal of Public Health, 100(2), 254–263. DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.156497.

Tang, Y. Y., Hölzel, B., & Posner, M. (2016). Traits and states in mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17, 59. DOI: 10.1038/nrn.2015.7.

Trammel, R. C. (2017). Tracing the roots of mindfulness: Transcendence in Buddhism and Christianity. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 36(3), 367–383. DOI: 10.1080/15426432.2017.1295822.

Treleaven, D. A. (2018). Trauma-sensitive mindfulness: Practices for safe and transformative healing. WW Norton & Company.

Vago, D. R., & David, S. A. (2012). Self-awareness, self-regulation, and self-transcendence (S-ART): A framework for understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 296. DOI: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00296.

Varela, F. J. (1996). Neurophenomenology: A methodological remedy for the hard problem. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 3(4), 330–349.

Van der Kolk, B. A. (1994). The body keeps the score: Memory and the evolving psychobiology of posttraumatic stress. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 1(5), 253–265. DOI: 10.3109/10673229409017088.

Weng, H. Y., Fox, A. S., Shackman, A. J., Stodola, D. E., Caldwell, J. Z., Olson, M. C., & Davidson, R. J. (2013). Compassion training alters altruism and neural responses to suffering. Psychological Science, 24(7), 1171–1180. DOI: 10.1177/0956797612469537.

World Health Organization. (2019). The WHO special initiative for mental health (2019-2023): Universal health coverage for mental health. World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/310981.

Zaki, J., & Ochsner, K. (2012). The neuroscience of empathy: Progress, pitfalls and promise. Nature Neuroscience, 15, 675–680. DOI: 10.1038/nn.3085.