| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2017) 3(2):28–40 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2017/3/4 |

Songkites – exploring the impact of a therapeutic songwriting project in post-conflict Cambodia

Songkites--探索治疗性歌曲创作项目在柬埔寨冲突后的影响

Ragamuffin International/Songkites, Cambodia

Abstract

Songkites is a therapeutic songwriting project. Its aim is to nurture creative expression, leadership and community through songwriting, production and performance with young people – both in Cambodia and in post-conflict contexts around the world. Following a devastating history, Cambodia is now re-building its creative and artistic identity. This paper explores how Songkites has contributed to the emergence of original songwriters and artists in popular youth culture. It also considers the impact that therapeutic music programs can have on both the individual and collective identity, and in post-conflict reconstruction.

Keywords: therapeutic song-writing, music production, Cambodia, post conflict, youth culture

摘要

Songkites是一个治疗歌曲创作项目。 其目的是通过与年轻人的歌曲创作、制作和表演来培养创造性表达,领导力和社区精神 – 无论是在柬埔寨还是在全球各地的冲突后环境中。 在破坏性的历史之后,柬埔寨正在重建其创造性和艺术的身份。 本文探讨Songkites是如何为流行青年文化中原创歌曲作者和艺术家的出现做出贡献的。 文章还关注了疗愈性音乐项目对个人和集体身份以及冲突后重建的影响。

关键词: 疗愈性歌曲创作, 音乐制作, 柬埔寨, 冲突后, 青年文化

Introduction

Songkites was ignited by the confluence of two phenomena: the high incidence of suicidal ideation in the young clients of Ragamuffin’s Arts Therapy Clinic for Cambodian children and adolescents and the prevalence in popular culture of Khmer music videos and movies which were filled with depictions of suicide, self-harm and accidents. In Cambodia, music videos are ubiquitous and uncensored and can be accessed in homes, on phones and even on public transport. This repeating narrative of relationship breakdown, trauma and crisis now plays itself out within youth culture.

The identification of these two ideas left clinician Carrie Herbert asking, “Can a new musical and video narrative be developed that can promote positive responses to challenges and distress? Can music carry the supportive, creative messaging of Ragamuffin’s1 therapeutic model to young people across Cambodia?” In 2013 Carrie – an Arts Psychotherapist/trainer and songwriter – began a collaboration with a professional musician and producer from Australia named Euan Gray. Euan was committed to the evolution of songwriting and professional music production in Cambodia, and in coaching young songwriters. This creative partnership between Carrie and Ewan would contribute to the creation of Songkites – which was founded as a therapeutic songwriting project that aimed to facilitate the creation and production of high quality, life-affirming original music in Cambodia. Since 2013, over 30 original songs have been produced and created at the Songkites Studio; now this paper explores the outcomes and impact of this unique programme.

Branding Songkites

Cambodia’s most-loved traditional kite inspired Songkites’ name. KhlengEk – literally meaning ‘a unique kite’ – are special, individually decorated kites carved out of bamboo; they are celebrated because they produce musical tones as they fly. These kites are flown to give thanks for bountiful harvests, or to mark the end of a period of war or conflict. Kites are wonderful symbols of freedom – and creating original music is about being free; free to be oneself and express oneself authentically through music (Gray & Herbert 2016). The Songkites image and branding was established to encourage emerging songwriters to take the opportunity to express their most valuable ideas and experiences through music and also to enable them to share this music with a wide audience across Cambodia. The Songkites brand became a living vehicle – sustaining and communicating its core ethos beyond each specific project as it became known across Cambodia for the production of original music.

Cambodia – the context of recent history

Between 1975 and 1979, the Khmer Rouge revolution resulted in the deaths of millions of Cambodians; an estimated 95% of the nation’s musicians and artists and 70-75% of the nation’s educators and higher education students died. The leaders of the regime declared 1975 as “year zero,” effectively erasing “over two thousand years of Cambodian history, money, markets, formal education, Buddhism, freedom of speech and movement” (Chandler 2008, 256). The once vital music industry of the 1960s faced almost total destruction under the Khmer Rouge regime and many artists were either killed or fled the country.

The return of music education was slow and was effected primarily through the work of NGOs engaged in restoring both traditional and contemporary arts. The Royal University of Fine Arts has played a dynamic role in developing the traditional arts while Music and Arts education still remains scarce in public schools.

The effects of this genocide are still being processed – not only by the generation which survived it, but also by their children and grandchildren too. Cambodia’s turbulent history demands that the emotional stories of both the past and present be addressed. Emotions which are channeled into such creative actions as music and songwriting will be less likely to be channeled into destructive actions.

Time for Remembrance Project

In November 2016, Songkites was commissioned by the Youth Resource Development Program to provide training for 5 young songwriting artists to remember the time of the Khmer Rouge and to consider their vision for the future. These artists gathered stories from grandparents, parents and elders within their communities in order to develop and catalyse ideas. The songwriters wanted to give voice to those who had been silenced. The songs not only channeled the history of events and experiences but also coupled those with powerful messages of hope and a determination to learn from the past.

I asked one songwriter, KanPich, why it was important to remember the Khmer Rouge time. This was his reply:

“A lot of people were killed and, with this opportunity for remembrance through music and songs, we hold this hope that it won’t happen again in the future. Music helps people to catch through melody and lyrics the meaning in the song – then they can receive the key message in the song. I wrote my song on remembrance because, as a child, when I heard about the tragedy from my mum I remember feeling so shocked and how it was totally unacceptable. My mum always wanted to know the answer to the question, why did this happen? Why did we kill each other? And who can answer this question? So my song asks her questions, gives her her voice – even though it may be impossible to answer – the question can be asked and the emotion can be expressed and the cry for this to never be repeated again”. (KanPich 2017)

In KanPich’s song, he enabled his mother’s voice to be expressed, to be heard and to be shared. During the time of the Khmer Rouge, one of the most powerful weapons was silencing the voices of the people. Fear was all-pervading; if anyone’s speech or actions gave an indicaton that they were educated or artistic, they would be killed. Through Songkites, the process of songwriting moves across generations and liberates the silenced voices; it enables the next generation to recover its voice. Through the creation of his music, KanPich was singing on behalf of his mother and, at the same time, on behalf of everyone whose voice had been silenced.

The music created through Songkites enables even the hardest facts and most difficult questions to be presented in a way that can be received. In SreyrathImara’s song, her beautifully haunting melody conveys – with hope and gentleness – many disturbing facts of the Khmer Rouge period together with her passionate plea for peace as she reflects:

“We cannot forget! The Khmer Rouge killed so many people – so tragic it made Cambodia live in so much suffering so much pain – we must not let this ever repeat. We can’t walk in the same path we have to change how we treat our people. Music is so important because it can help heal people’s heart. Music can speak what we don’t actually want to say or can’t physically speak out. Music can relax the heart and bring peace. Lyrics can express and communicate what we want to say – we can remember the past and also have something to be hopeful for in the future. My song is about remembering this painful past and asking for peace. I want to ask Cambodian people and our neighbors for peace. We don’t want war again. We are living in a developing country, and it’s so important for Cambodian young people to learn from this past, join hands together and make this country to be a better one”. (SreyrathImara 2017)

In a country that still faces many societal problems, Songkites aims to create a channel through music that can bring peace to the hearts and minds of young people. Songkites’ therapeutic approach aims to empower and serve young people at many different personal, creative and societal levels – artistic, expressive, identity, well-being, leadership and social consciousness.

“I really think my music and the music from Songkites helps young people in Cambodia to believe in who they are and believe in themselves. If we believe in ourselves, we can rebuild a stronger Cambodia for the future”. KanPich (Songkites Season 1 2014)

Where the rivers meet – the Songkites curriculum

The Songkites curriculum stands at the intersection between music and therapy. Songkites brings these rivers together intentionally. Phnom Penh – where this curriculum was developed – is where the Tonle Sap and the Mekong rivers meet before they converge to flow down into Vietnam to the sea. The merging of these rivers has become a metaphor that mirrors the aim of the Songkites program; to bring together professional music production with creative arts therapy, personal development and self-care in order to nurture the creative lives of young people in Cambodia (Gray & Herbert 2016).

Participatory Action Curriculum Development

The founders of Songkites developed a participatory action approach to the development of their curriculum. Carrie Herbert (the Arts Psychotherapist and Singer/Songwriter) and Euan (the professional musician) developed a peer-based supervision model that would encompass the complementary and shared dimensions of the Songkites training program. Carrie Herbert developed her songwriting, recording and performance techniques through a coaching process with Euan. This experiential approach also enabled both Carrie and Euan to develop a stronger tool kit in supporting the songwriting and music production elements of the course.

Euan developed his coaching and therapeutic support methodology through his creative arts supervision sessions with Carrie and, in doing so, was able to bring an increased therapeutic dimension to all stages of the coaching program. This collaborative partnership modeled the same evolution imagined for participants and resulted in greater awareness, improved sensitivity and increased skill while also fostering teamwork that would further strengthen the therapeutic content of the program.

Euan and Carrie – as expatriates living in Cambodia – recognized the importance of having Cambodians who could speak fluent Khmer on the Songkites programme. In the second year of Songkites, they recruited a Cambodian musician, coach and assistant producer named SoriaOung. Soria – a graduate of Songkites Season 1 – strengthened the course in terms of language, cultural awareness, youth culture, understanding and leadership; he also had direct experience of the Songkites training methodology. He reflects on the team’s approach: “Together we professionally can show people new ways, enlarge their capacity and help them to do the very best for themselves, their songs and careers.” SoriaOung (2017)

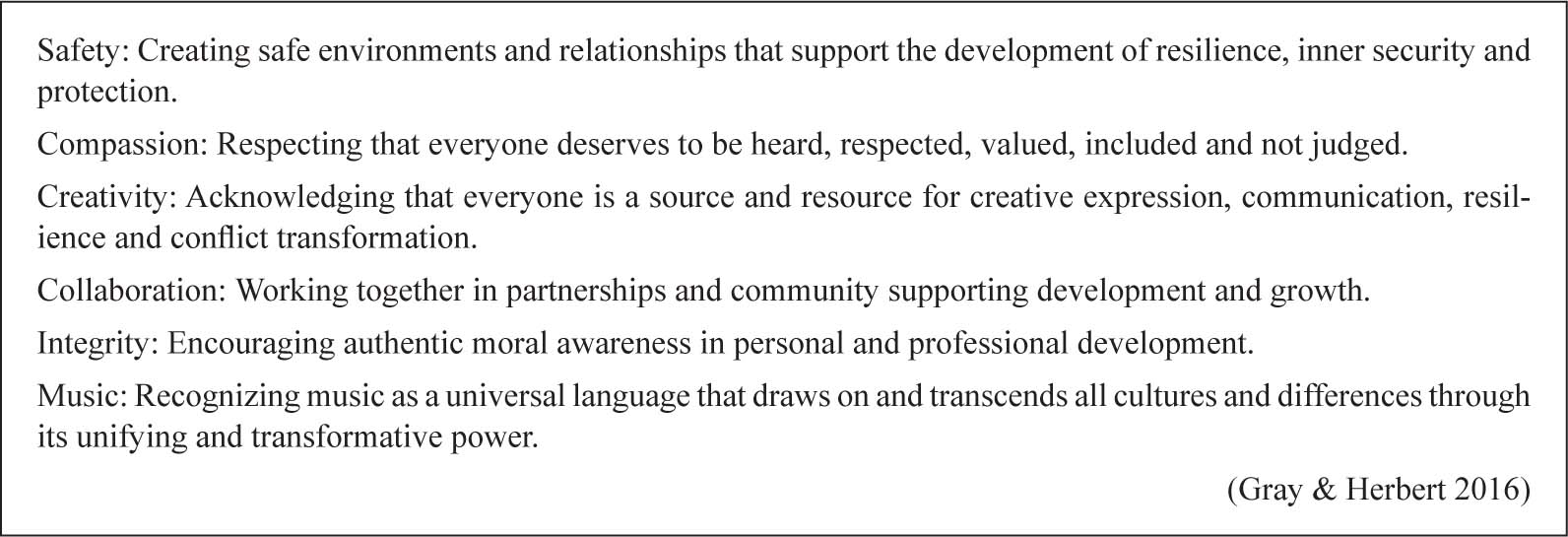

The Songkites curriculum was further developed to include a Diploma in Songwriting, foregrounding personal development, creativity, the craft of songwriting, skills development in recording and performance, self-care and leadership. The Songkites method is built from the core values of safety, compassion, collaboration, creativity and music (see figure 1).

FIGURE 1 | Songkites Core Values.:

Music is a value in itself – but is also central to and informed by the other values – creating an inter-related framework that inspires every element of the course. These values shape the aims of the project (See figure 2).

FIGURE 2 | Songkites Aims.

Outcomes

Breaking new ground – and the power of saying sorry

In 2013, the Songkites method was piloted as ‘Songkites Season 1.’ Twelve young people aged between 17 and 28 took part in a program of workshops, artist development and recording that culminated in an album launch concert in Phnom Penh in 2014. The event showcased the Songkites artists in a multimedia performance to an audience of over 4000 people. “Songkites has broken new ground today in the presentation of original music in Cambodia” (NRG Radio). The album was distributed locally and worldwide through online media channels to 95 distribution outlets – resulting in over 6 million streams. A number of the songs became national hits and some of the songwriters have gone on to become successful household names in Cambodia.

Jimmy Kiss is one of these artists. His song “Baby I’m Sorry” has become one of the most popular songs released since the 1960s. He comments:

“My fans tell me it is such a famous song because it was the first soulful song in Cambodia since the war. They said they heard a singer who could sing from his soul – yes it’s true I used my soul, the real thing inside to sing it, it’s from my deep heart and I want to share this feeling to the world” (Jimmy Kiss 2017)

In the context of Cambodia – where so much can never be reconciled or brought to justice and forgiveness remains multi-layered and complex – Jimmy’s song exists as a unique channel for expression and the embodiment of someone’s ability to express an apology within a relationship. This is both inspiring and liberating.

“Everyone knows they makes mistakes, but it’s hard to say sorry sometimes, they can talk with the song instead and use the song to find their own voice – it’s helping people to be able to say sorry.” (Jimmy Kiss 2017)

Come Home for Dinner – a new narrative and road safety video campaign

Nikki Nikki created her first original song called “Home for Dinner.” This was a song about a child longing for connection with her father. Here is an extract from the lyrics:

So many things aren’t right/I try to tell you some things aren’t worth the fight/If you open up your mind, show me your heart/It would help to fix these broken parts/I need you to listen, I need you to care/Like a bird with a broken wing/I fall to the depths of my despair/Come home for dinner, come home to each other/It really matters to me/Forgive me if I ask for too much/but forget about being judged/Cause I won’t judge.

Nikki Nikki: Home For Dinner

This song about the longing for family touched the hearts of many young people across Cambodia. Its soulful message became a new narrative as it honored and expressed suffering, expressed the longing and need for a relationship and openly mentioned ‘coming home to each other’. It was also used for a National TV commercial and road safety campaign that aimed to reduce the number of traffic accidents during the National Holiday PchumBenh – a ceremonial time where Cambodians honor parents, elders and ancestors. It is also a time when there is a real increase in accidents. TVC positively promoted the concept of families “coming home to each other” and this song was played extensively on TV and radio during that time. It remains a popular hit today.

‘Season of Love’

The second album of Songkitestheme was entitled “Season of Love: Come Together; a social enterprise focusing on igniting change in Cambodia through imagination, creativity and collaboration using media, art and social entrepreneurship – and invited Songkites to create a soundtrack of original songs for their Khmer movie “Love to the Power of 4.” Themes from the movie spanned all dimensions of love and relationships and enabled participants to explore and navigate this complex and vital subject. Nine songwriters aged between 18-26 years took part in the journey to create, record and perform new music that explored such themes as relationship breakdowns, gay marriage, self-harm and suicide and conflict mediation as well as passion and a celebration of love in contemporary Khmer youth culture. The film premiered to a full house at the main multiplex cinema in Phnom Penh. It featured one of the Songkites artists portraying a positive and loving gay relationship that led to marriage. Recently signed to a national record label, Sam Rocker has become an icon and role model to young people in Cambodia with her powerful gritty pop rock anthems.

Changing times – Women in the music industry

Historically in the music industry, women are expected to make relational or sexual offers in exchange for opportunities and success. Such cases continue to be documented through the media. Knowledge of this imbalance of power and possible sexual manipulation creates fear within families when their daughters express an interest in developing a music career. Women artists also experience a high degree of vulnerability and fear when stepping out into the public arena. This has been a major issue for some female participants – with family members refusing to allow them to undertake TV appearances or perform in public concerts. Such challenges produce a high degree of anxiety for female artists who are trying to maintain integrity and power while, at the same time, feeling vulnerable. Songkites has supported the female artists in question and has built relationships with their families – thus increasing female performers’ profiles and creating more dialogue on the role of women within the industry. Songkites’ aim has been to create safer and more respectful opportunities for female artists – allowing them to have a positive experience of performance that empowers them. Over the past three years Songkites has seen significant progress in the image and perception of female artists; these women have worked hard to demonstrate and personify integrity both on and off the stage.

Cambodia is a culture in transition. The traditional Khmer culture and values often combine and sometimes clash with contemporary Western-oriented youth culture. The public presentation of these young performers’ art is watched and monitored – approved of or disapproved of – in the public sphere. Ongoing artist support and care-filled management is essential in helping artists to navigate these complex issues.

Navigating social media and its impact on identity and wellbeing

As participants have risen to fame through social media, this has brought with it a new set of challenges. Unfortunately, self-worth, value and identity are often impacted by the number of Facebook likes someone receives for a post. Criticism on social media streams is common. Songkites has found itself supporting songwriters in engaging professionally with social media and in giving guidance on how to become responsive rather than reactive or defensive. Artists have faced a number of challenges online: media accounts have been hacked and identities have been stolen. Hackers have even managed to close down the Facebook accounts of very successful artists. The impact of the hacking culture has even impacted Songkites directly, as our own Facebook page was hacked this year and we subsequently lost our entire online history. Such an attack has demonstrated the fragility of these platforms – and is also highly impactful as these are the primary social media base of the music industry in Cambodia.

The personal self-care and well-being of artists remains paramount in the navigation of these ongoing and newly emerging challenges. Songkites teaches about self-care, well-being and media management. There is, however, is a need for ongoing support as situations and incidents continue to develop and emerge.

Navigating fame, success and the music industry is an incredibly complex task and impacts on fundamental core issues of identity and personal values. The inner security of the artist is vital in maintaining a robust and resilient personal identity. Songwriting is an inherently vulnerable process and the presentation of the real and raw self can often leave an artist exposed. For a creative artist, learning to protect himself/herself whilst staying true to their art requires deep reflection, maturity and ongoing support. Artists often bring complex issues to the foreground as they voice the challenges of contemporary Cambodia. Issues relating to gender identity and sexuality, self- harm, human rights, the empowerment of women, and power relations have emerged alongside a stream of popular songs focusing on love and relationships. It is clear, then, that addressing these themes through music and music video production remains an ongoing challenge. Ideally, we would wish that each stage of creation – from songwriting through to video production and public presentation – be embedded within the therapeutic values that support and enable the artist to be at their best and to present their most powerful art with honesty and integrity. Navigating others’ needs, agendas and the detail of contracts is incredibly complex and can often be confusing, compromising or contradictory for an artist. Advocates and experienced artist managers are vital components at every stage of an artist’s career and their presence and support allows the artists to focus on the strengthening of their decision-making skills, the building of their self- determination, and the development of their leadership skills – all of which enhance the creative capacity of the artists themselves.

Developing Identity in Young People

A significant body of research has emphasized the role of music in the processes of both self-development and identity (Larson, 1995; Ruud, 1997; DeNora, 1999; North and Hargreaves, 1999), as well as social identity and empowerment (Tarrant et al. 2001; Shepherd and Sigg, 2015). Baker (2013) asserts that when the music created matches the musical identity of the songwriters, creating songs becomes a medium to allow them to connect or reconnect with their sociocultural identity (Baker 2013). Songkites aims to enable people to create authentic songs that are true imprints of each individual and their experience. From a therapeutic perspective, songwriting and music are resources that allow people to reclaim and reawaken a seemingly hidden self-identity and serve to reaffirm self-identity – making sense of one’s own identity and constructing a new identity (Koelsh, 2013). PuthikaCheab reflects on the impact of Songkites has had on his sense of self:

“I had always known singing and songwriting are my passion but didn’t know where to start because I was unsure, unconfident, and scared until I joined Songkites. I was a person with self-doubts and a lot of insecurities. There was always a voice telling me I wasn’t good or talented enough to be a singer-songwriter, but when I was in Songkites, I learned how to free myself from those self-doubts and insecurities. I didn’t have to wear faces. Everything was raw, authentic, and original from the bottom of my heart, and there wasn’t a single moment that I felt judged. That’s when I was able to give my all to the song recording in the studio and the performance in the concert. In Songkites, I found love, encouragement, inspiration and compassion – all of which have made me become more confident, open to differences and positive toward things around me. I’ve learned to love myself, respect my true talent, and be proud of who I am” (PuthikaCheab 2017)

How can we define our identity?

The first creative exercise on day 1 of Songkites involves creating an image in response to the question “what is my essence, the core of who I am?” Exploring these images becomes a new way of articulating identity, liberating creative metaphors, phrases and lyrics that can then be used as opportunities for personal reflection and song-crafting – the process of creating a song. This dynamic process takes participants deep into their creative resources, their personal beliefs and their values and experiences.

In Season 1, KanPich wrote a song called ‘Who I Am’ which was an embodiment of his exploration of his meaning of identity. A powerful ‘soul’ song became a vehicle into which he could step into the fullness of his voice and so discover and affirm a more empowered sense of self. This song became a catalyst for KanPich as he says:

“I decided to write ‘Who I Am’ as my very first song to express myself through its lyric; it helped me discover my passion and dream. I want people to have faith in their dreams and visions. We can be who we are regardless of our pasts or biographies. Songkites gave me a chance to find myself through songwriting, and this helped me see what I could achieve in life and trust myself that I can do it. Now 3 years later, I see how my songs have inspired a lot of young people to follow in my footsteps. I have become who I am. In the future, I hope to bring the quality of Khmer music more and more to an international audience. So as Khmer artists, we will be able to develop our own identity and show the world who we really are and not be defined by the past”. (KanPich, 2017).

Pich has gone on to become very well known in Cambodia – both through his music and in his acting career.

Music crossing borders – building relationships in conflict areas

“But what makes music special – what makes it special with regards to identity – is that it defines a space without boundaries. Music is thus the cultural form best able both to cross borders – sounds carry across fences and walls and oceans, across classes, races and nations – and to define places; in clubs, scenes, and raves, listening on headphones, radio and in the concert hall, we are only where the music takes us”. (Firth 2011 page 125)

Yorn Young – a traditional Tro player and songwriter from Songkites Season 1 – is passionate about bringing together traditional and contemporary pop music. He has had an opportunity to travel to the United States and experience how powerfully music can bring people of many cultures together in a new synergy and fusion. He recalls an experience on the Thai/Cambodia border where he was stopped by Thai soldiers and questioned about the case he was carrying. Tense moments ensued as the soldiers assumed he was carrying a weapon, Yorn opened his case to show them what was inside. He was carrying a Tro – a traditional bowed string instrument. Its body is made from a special type of coconut covered on one end with animal skin and it has three silk strings. Relief followed as the soldiers realized Yorn was not a threat either to them or their country. Yorn proceeded to take the Tro out from its case and to play it in order to show the soldiers how it sounded. Soon they were all singing and dancing at a border that is a critical point of conflict between the two countries.

“I think music can heal people in many ways based on my experience. My father is a musician and survived the Khmer Rouge; he lost his leg from a land mine accident. I think playing music helped him begin to heal. I remember him rehearsing the Tro at home when I was small; he inspired me to play it and find a way to let music cross the borders of hatred. Music is for everyone – it is without enemies and borders. It can stop discrimination and hatred between people. We can bring music to our enemies. For example, Thai and Cambodian people have not felt good towards each other for hundreds of years, but when I played this music for them it is as if I am their friend. They loved the music I played, there was no border between us” (Yorn Young 2017)

Political protection and safety

The political relationship between Cambodia and neighboring countries demands both sensitivity and respect. Songkites is, by policy, an apolitical organization and its media policy clearly states that participants do not engage in political debate or dialogue. This is primarily for the protection and safety of artists and the organization. Songkites promotes freedom of expression and sensitivity to cultural and political contexts – especially in the presentation of songs, image and opinions. Specific coaching and preparation for public performances, interviews and TV appearances is vitally important in enabling Songkites participants to navigate this area with confidence. Those in positions of fame and public success have a responsibility to present their opinions and views (within a Cambodian context) in a respectful and considered way. Singers and artists in Cambodia are now required to be the new role models for youth culture.

Role models and leadership

Cambodians are proud of their artistic cultural heritage, but contemporary songwriters often lament their inability to match the artistic depth of their ‘golden era’ role models from the 1960s. Songkites aims to develop people as role models. Frith (2011) describes how identity comes from the outside not only the inside; it can be something we put or try on, not only something we reveal or discover from within (Frith 2011 page 121). The process of ‘trying on’ is seen in the increasing popularity of posting cover songs on Facebook or YouTube. This is a literal, lyrical ‘trying on’ as musicians seek to express their embodiment of the song, its meaning, music and the artist – their ‘idol’.

SoriaOung, whose 2015 song Nek oun ban tremsromai has over 460 covers, responds to the word “Idol” and the concept of being a role model in the music industry. “The word ‘idol’ is to express who you’re supporting; for me ‘idol’ is such a big word to use for anyone. People need us to raise us all up to another level. It feels [such] an honor to be a pioneer for the music industry. It’s not an easy job to do, but it’s such a privilege to explain and direct people to do what is right for the industry and for the nation. Now we can actually see some changes to it. More original songs are blooming everyday and being spread across the country. Music is my identity. The fact that Songkites gathers new artists like a team and releases albums strengthens the music industry. Songkites peels off another layer of doubt from those who love music and shows that when we’re one, we can keep pushing music to another level.” (SoriaOung 2017).

The songs that emerge from the Songkites method explore and address many important issues and themes that are relevant to many young people today. As artists confront the hard edges, deeper challenges and societal prejudices through their music, they do so as role models. As Sam Rocker explains: "I think I am a role model for those who struggle in life. I want to inspire people that nothing is impossible as long as you believe in yourself and keep doing what you love and what you are good at. Regardless of looks or appearance, anything is possible if you put your heart in what you believe in and spread it to the world. Be true to who you are and people will love you for who you are. I want to represent the voice for the voiceless." (Sam Rocker 2017)

Jimmy Kiss reflects on this further – “It’s like they use me, they say; ‘Jimmy Kiss is my hero.’ They use my character for what they need and I try to encourage them to see what they have in their hands already; then they feel that they are enough ready to do it. When I travel into the provinces and into the jungle they come and they talk to me. They talk to me as a brother. In the Khmer Rouge times if you were a hero of Cambodia – a doctor, a teacher, an artist – you died. They had to lie to survive, they killed the heart of the hero in the life of Cambodia but I believe the hero is in the heart of people and I am calling for the hero to be restored in the heart of Cambodia. I know now I was born to be a singer – I wish my music and my songs can be the voice of the hero to call back the heroes in the hearts of Cambodians” (Jimmy Kiss 2017)

Conclusion

Today, it’s not unusual to see guitars on the backs of young people driving through Phnom Penh on their motos – a stark contrast to my view of youths carrying AK47’s on their back (which was what I saw when I first arrived in Cambodia in 1993). Music schools and Khmer original music are now beginning to flourish in Phnom Penh. In the Songkites studio with producer Euan Gray, Nikki Nikki has just finished recording a powerful song that explores the subject of suicide.

The challenge now is to find the resources to continue to support, enable and nourish young people and to equip them with creative channels for living within an emerging society that still faces many social and economic challenges. Therapeutic music programs such as Songkites have had a major impact on the development of popular music and artists. Now, more ongoing research is needed to demonstrate its effectiveness and application in other post-conflict contexts around the world.

About the author

Carrie Herbert – MA, PGCE, IATE, UKCP, CAGS Dip, PHD Candidate , Co-founder/Director of Arts Therapy Services for Ragamuffin International/Cambodia, Integrative Arts Psychotherapist, qualified Trainer, supervisor and consultant. Carrie has extensive experience in the following areas: refugees and asylum seekers, mental health, trauma and abuse, conflict and post conflict work. She is a specialist in therapeutic training, staff well-being programs, therapeutic supervision, and organizational development. Carrie also co-founded Songkites – a therapeutic music program in Cambodia. She is a songwriter, musician and photographer with an avid interest in the arts for expression, social action and transformation.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the artists, co-founder Euan Gray, the Songkites team and all its sponsors in enabling the creation of this program in Cambodia.

5 Songkites is a project of *Ragamuffin International / Cambodia, a Creative Arts Therapy NGO founded by Carrie Herbert and Kit Loring in Wales, UK 1999/ Cambodia 2001.

References

Baker, F. A. (2013). What about the music? Music therapists’ perspectives on the role of music in the therapeutic songwriting process. Re-published in Sage Journals, 43(1), 2015. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0305735613498919.

Chandler, David. (2008). A history of Cambodia. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.

DeNora, T. (1999). Music as a technology of the self. Poetics, 27, 31–56. 10.1016/S0304-422X(99)00017-0.

Frith, S. (2011). Music and identity. In S. Hall, & P. Du Gay (Eds.), Questions of cultural identity. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Gray, E., & Herbert, C. (2016). Songkites diploma in therapeutic songwriting. Unpublished Curriculum. Ragamuffin Boathouse, Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

Koelsch, S. (2013). “Striking a chord in the brain: Neurophysiological correlates of music-evoked positive emotions”. In T. Cochrane, B. Fantini, & K. R. Scherer (Eds.), The emotional power of music. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Larson, R. (1995). Secrets in the bedroom: Adolescents’ private use of media. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 24, 535–550. 10.1007/BF01537055.

North, A. C., & Hargreaves, D. J. (1999). Music and adolescent identity. Music Education Resource, 1, 75–92. 10.1080/1461380990010107.

Ruud, E. (1997). Music and identity. Nordisk Tidsskrift Musikkterapi 6, 3–13. 10.1080/08098139709477889.

Shepherd, D., & Sigg, N. (2015). Music preference, social identity, and self-esteem. Music Perception, 32, 507–514.

Tarrant, M., North, A. C., & Hargreaves, D. J. (2001). Social categorization, self-esteem, and the estimated musical preferences of male adolescents. The Journal of Social Psychology, 141(5), 565–81.