FIGURE 1 | Greenout poem.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2024) 10(2):283–303 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2024/10/22 |

Redefining Creativity and Well-being: A Feasibility Study for a New Course at a Small Liberal Arts College in Japan

重新定义创造力与幸福: 日本一所小型文理学院开设新课程的可行性研究

1Akita International University, Faculty of International Liberal Arts, Japan

2University of Minnesota Rochester, Medicine and Arts, USA

3Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Minnesota Medical School, Masonic Institute for the Developing Brain (MIDB), USA

Abstract

Considering the escalating mental health needs of college students and the stigma surrounding mental illness in Japan, this study explores how creativity impacts student well-being. Eleven students enrolled in an intensive 2-week course participated in the study, completing the Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving (CIT) and post-course interviews. Total CIT scores increased significantly from pre- to post-course (p=0.04). Post-course interviews suggested eight themes, three of which are explored here: safe spaces, redefining creativity, and self-acceptance and self-compassion. The article includes a case study of one student’s learning journey to synthesize quantitative and qualitative findings. This preliminary study finds that creative activities, combined with learning in positive psychology, can help college-level students in Japan achieve a greater sense of well-being.

Keywords: creativity, well-being, positive psychology, students, arts

摘要

考虑到大学生日益增长的心理健康需求和日本人对心理疾病的偏见,本研究探讨了创造力如何影响学生的幸福感。十一名注册了两周强化课程的学生参与了此项研究,并完成了《全面繁荣量表》 (CIT) 和课后访谈。CIT总分从参课前到参课后大幅提高 (p=0.04)。课后访谈提出了八个主题,在此探讨其中三个主题:安全空间、重新定义创造力以及自我接纳和自我慈悲。文章通过对一名学生学习历程的案例研究,综合了定量和定性研究结果。这项初步研究发现,创造性活动与积极心理学的学习相结合,可以帮助日本大学生获得更多的幸福感。

关键词: 创造力, 幸福感, 积极心理学, 学生, 艺术.

Introduction

Well-being has become a concern for schools at all levels in Japan, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, the number of elementary and junior high school students refusing to go to school increased dramatically, with one out of 20 middle school students refusing to attend school (Kimura, 2022). Among reasons for suicide, “school” ranked highest for Japanese youth between January 2020 and May 2021, higher than “family,” “health,” and “relationships” (Koda et al., 2022). Even before the pandemic however, UNICEF’s 2020 report on child well-being ranked Japan 37th out of 38 countries in mental well-being (Gromada et al., 2020). Japan’s competitive academic environment is well-known. Among East Asian Nations, Japanese students are among the top achievers in mathematics but report the lowest sense of belonging (Montt & Borgonovi, 2018). Middle schoolers increasingly worry about high school examinations that determine paths to further education and careers. As in most high schools, their classrooms are teacher-centered and lecture-based, leaving little opportunity for student expression beyond expected answers (Fukuzawa, 1994). Japanese education typically makes use of a “gap approach,” in which teachers identify “missing pieces” in student knowledge and attempt to fill them through rigorous effort. This mentality stems from “negativity bias,” the concept that negatives demand more focus than positives (Baumeister et al., 2001). These early educational experiences may set the stage for reduced well-being among university students in Japan. The COVID-19 crisis, which led to worsened mental health challenges in university students globally (Zarowski et al., 2024), provided a long overdue impetus to examine student well-being in Japan.

Background

Stigma and the Mental Health of Japanese Students

In Japan, many view mental disorders as untreatable. Those with mental illness often experience exclusion, which can exacerbate symptoms (Ando et al., 2013). This stigma has prevented a thorough examination of mental illness on a large, public scale. The Basic Act on Suicide Prevention was passed by the Japanese government (Umeda, 2016) in response to the World Health Organization’s request to address the nation’s high number of suicides (Koda et al., 2022). However, the current crisis in schools will continue until curricular reforms are initiated (Gromada et al., 2020) to help youth and young adults develop well-being and navigate high levels of academic stress. Suicide is the top cause of death among college students in Japan. With 350 student deaths reported annually (Takahashi et al., 2023), “only 10–20% of students who died by suicide in Japan were connected to on-campus resources such as student counseling” (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, 2021, 2022, as cited in Takahashi et al., 2023). Compared with college students in the United States, Masuda et al. (2007) reported that Japanese psychology majors surveyed had higher tolerance for stigma when seeking mental help. However, they also had less prior experience talking with mental health professionals and less interpersonal openness in sharing feelings.

Arts in Health

The connection between arts and health has recently been studied through varied methodologies and disciplines. A recent scoping review of over 3,000 studies found evidence for the impact of arts in promoting wellness as well as in the prevention and treatment of illness (Fancourt & Finn, 2019). For example, research has demonstrated an impact of arts on key mental health outcomes, including reduction of stress and anxiety (Abbing et al., 2019; Erbay Dalli et al., 2023; Tang et al., 2019), emotional regulation (Dingle et al., 2017), enhanced self-view and efficacy (Yue & Peng, 2022), improved healthy behavior (Rodriguez et al. 2024), and social resilience (Fancourt et al., 2016). Within this broader scope, the current study considers arts engagement as a strategy to promote well-being in college students. As opposed to art therapy, which is provided to patients by certified art therapists (American Art Therapy Association, 2024; Van Lith & Spooner, 2018), the current work falls under Arts in Health programs facilitated primarily by artists aiming to promote well-being among college students through the creative process (National Organization for Arts in Health, 2024; Van Lith & Spooner, 2018).

This study posed two questions: (1) How does engaging in the creative process and learning about positive psychology impact participants’ understanding of well-being? (2) How will students view their own well-being after taking the class? We predicted that by engaging in this course, students would understand how their own creativity connects to their well-being, resulting in a deeper sense of their own well-being. If successful, the course could provide a model for educational programs that address mental health needs of a wider range of students in Japan. Implementing such programs might also reduce stigma in communities.

Methods

Setting

Teachers carefully selected the classroom: an open, cedar-paneled space with large windows and tables to seat groups of five. Rare in Japanese universities, the classroom was designed so students and teachers could walk freely around the room, chat, and see each other’s work. This open-spaced classroom was important for students’ learning; as Bachelard (1958) said, “Outside and inside are both intimate” (p. 217). Within this intimate space, students could become more at ease with potentially unsettling self-reflection.

Curriculum

The interdisciplinary team of teacher-researchers designed the curriculum to provide holistic and novel ways of rethinking well-being. The 10-day course took place for 2.75 hours each morning (including short breaks). Beginning with 20 minutes of yoga with a yoga expert for eight of the mornings, students then participated in creativity and well-being activities for the rest of the session (see Table 1). Completing reflective journal entries each day after class, students completed the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA) Survey before the first class for their own information and discussion with peers (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Three of the sessions took place virtually (two planned, one due to weather).

TABLE 1 | Curriculum for the Creativity and Well-being Course

| Day 1 | Positive psychology 1 Definition and Rationale: The scientific study of “the conditions that make people flourish,” positive psychology was employed to create a safe learning environment and help students rethink how skills and knowledge are acquired (David et al., 2014, p. 1). Developing the classroom as a “judgment-free zone,” teachers emphasized that they were not seeking correct answers and that various opinions were welcome. After establishing ground rules for a safe space, day 1’s teacher, a registered Positive Psychology Consultant®, introduced the “gap approach” and “negativity bias” (alluded to above). Countering this, students reviewed and discussed results of their VIA Survey focusing on their strengths. |

| Day 2 | Visual art studio 1 Definition and Rationale: An evidence-based practice that can lead to changes in “self-esteem, creativity, and anxiety levels,” the visual arts provide a non-verbal focus on image-making that can “give rise to significant intrapersonal and interpersonal change” (Gilroy, 2006, p. 9). In Visual art studio 1, day 2’s teacher reinforced the theme of a “safe space” and helped students explore their sense of safety and self-contributions to well-being. A visual artist who is also a therapist and educator facilitated the drawing of a personal safe space through memories and imagination. Students then made a clay “mini-me” to represent themselves, discussing their creations in small groups. |

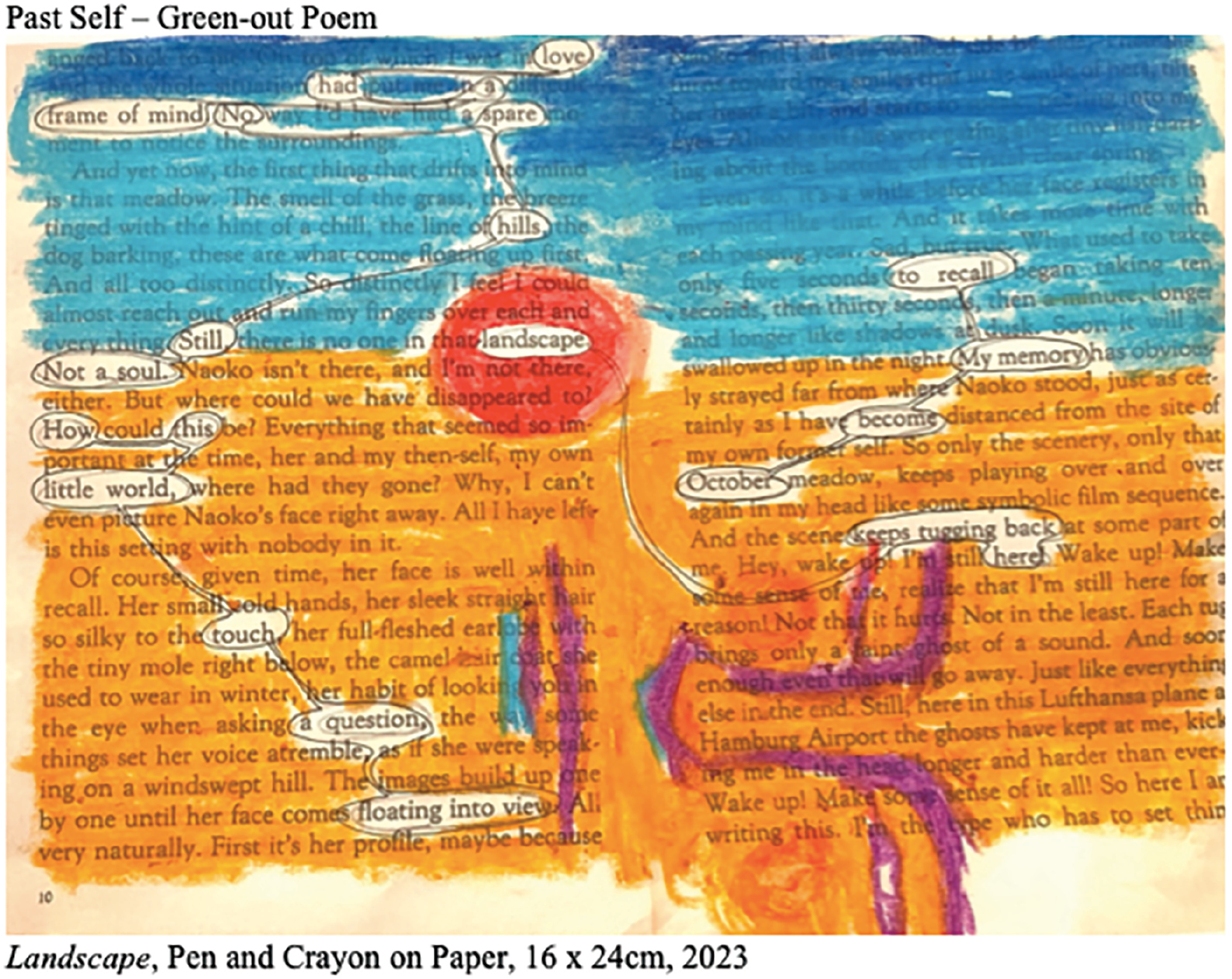

| Day 3 | Creative writing Definition and Rationale: Tapping into the verbal expression of emotions and experience through the use of images, rhythm, and sound, creative writing has been shown to have positive effects for mental and physical health (Pennebaker & Chung, 2011), facilitating a positive outlook and reducing distress about negative life events (Frattaroli, 2006). Led by two poet-educators, students used pages from Haruki Murakami’s Norwegian Wood to construct a “greenout” poem (commonly known as an “erasure” poem), titled “The Forest Inside Me” (see Figure 1). Students next explored their senses and forest memories through Imaginative Forest Bathing and freewriting. |

| Day 4 | Drama 1 Definition and Rationale: Drama is a form of art and embodied learning that can be used in the classroom to consider individual and community well-being (O’Connor & Gregorzewski, 2022). Guided by a drama specialist and educator, students warmed-up with Zip: Passing their energy around a circle, they communicated playfully with classmates, expressing different emotions. Students then explored stereotypes in improvised role plays, using characters and storylines from Little Red Riding Hood. |

| Day 5 | Mindfulness meditation and interpersonal and public expression (online session) Definition and Rationale: “Drawing attention beyond the usual mental activity to deeper levels of rest and clarity,” meditation gently “teach[es] the mind to develop the habit of attentive awareness in daily life” (Erricker & Erricker, 2001, p. 6), a practice that, if continued, can help students minimize depression and the tendency to ruminate on the past (Hemo & Lev-Ari, 2015). “Both personal and introspective as well as public and communal,” interpersonal and public expression facilitates empathy with others through sharing ideas, experiences, creativity, and personal growth (Pandian et al., 2014, p. ix). Students began with meditation and deep breathing facilitated by a meditation expert. Next, a teacher of communication arts guided students in techniques for self-expression through small group public speaking to prepare for the final presentation the following week. |

| Day 6 | Mental health and positive psychology 2 Definition and Rationale: Addressing a dearth of information about mental illness at Japanese universities (Takahashi et al., 2023), this session aimed to inform students about de-stigmatizing mental illness (see day 1 for the definition and rationale for positive psychology 1). A psychiatrist presented scientific and health perspectives about mental illness and treatments. Reflecting on mental health, well-being, and stigma in this session, students then further discussed strengths and negativity bias, solidifying ideas with the teacher who introduced positive psychology on day 1. |

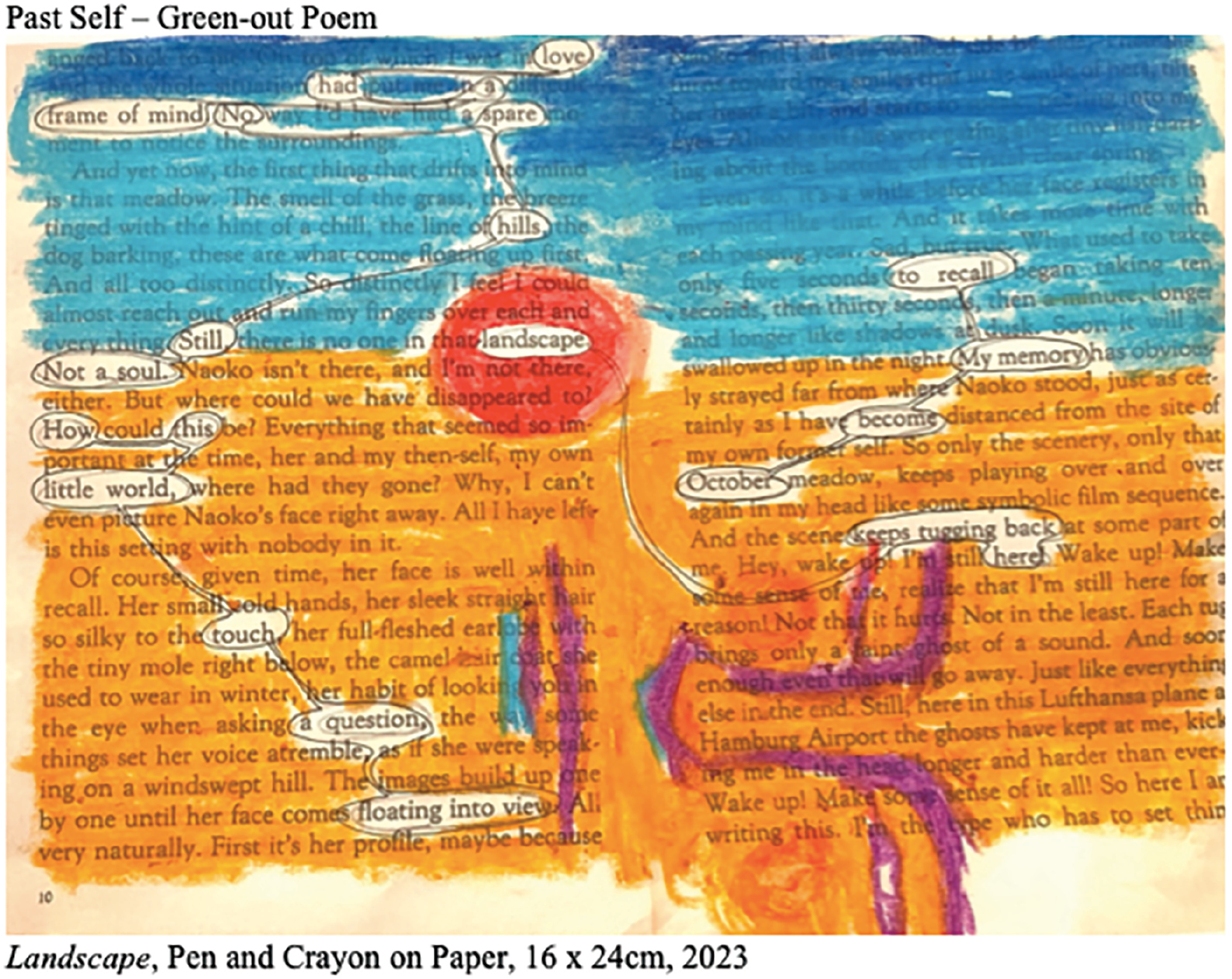

| Day 7 | Creativity Definition and Rationale: Based on the definition of creativity as a skill to navigate uncertainty (Cremin & Chappell, 2021), students benefit not only by doing creative activities, but by understanding the creative mindset and its connections to well-being. A poet and Arts in Health scholar introduced the link between the artist mindset and resiliency, as well as a puzzle-based self-portrait to practice applying the artist mindset (see Appendix A and Figure 2). |

| Day 8 | Drama 2 (online session) (See day 4 for the definition and rationale for drama.) A performance opportunity based on day 4’s drama workshop, day 8’s emphasis was on negotiation and reasoning in order to strengthen communication skills by sharing opinions in a fictional setting. |

| Day 9 | Visual art studio 2 (See day 2 for the definition and rationale for visual art studio 1.) Students stepped out of their comfort zones, imagined the places they would travel, and drew various team visions collaboratively on one sheet of paper for “Travel Together.” |

| Day 10 | Final, small group presentations (online session) (See day 5 for the definition and rationale for interpersonal and public expression.) Students articulated their learning outcomes and discussed them through the artwork they had created in small group discussions facilitated by teachers |

FIGURE 1 | Greenout poem.

FIGURE 2 | Self-portrait puzzle.

Study Procedure

Students enrolled in the Creativity and Well-being course described above were invited to participate in the study. Non-teaching members of the research team informed students of the study’s details, assuring that their participation would not impact their academic performance assessment. The informed consent procedure (in compliance with relevant universities’ institutional research boards or the equivalent) was completed before the first class.

Study participants completed the Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving (CIT) (Su et al., 2014) before the first and after the last class. Containing seven core dimensions (relationship, engagement, mastery, autonomy, meaning, optimism, and subjective well-being), the CIT measured the psychological well-being and the holistic perspective of positive functioning of study participants (see Appendix B). Participants were interviewed after the course and also 6 months later. Artifacts collected through the course consisted of daily reflection journals, final portfolios, and presentation videos, all articulating reflections on artwork created during the course and learning outcomes.

Interview questions (see Appendix C) were developed by the interdisciplinary team members. Prior to the interviews, interviewers reviewed the students’ course work (journals, portfolios, and final presentations) and used them to personalize the interview questions. Interviews were conducted and transcribed by the interdisciplinary team, who were present throughout the course. A native speaker of Japanese was on each paired interview team to translate if students encountered difficulties using English.

Data Analysis

Quantitative Analysis

Paired t-tests were used to evaluate change in thriving from pre- to post-course. We also explored changes in the seven CIT dimensions and (when relevant) their subscales (see Appendix B).

Qualitative Analysis

The data from the post-course interviews were examined through both team-based and individual reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2022). After transcribing interviews and then transferring participant quotations that best answered the interview questions onto a spreadsheet, the six interviewers analyzed their three to four interviews to identify an unlimited number of “emerging themes.” The lead writer selected codes from those suggestions while analyzing the spreadsheet data to determine eight final themes, three of which are described below. Supporting qualitative evidence for the themes was also gleaned from the 6-month interviews and participants’ final portfolios.

Case Study

One participant was selected for an explanatory case study (Priya, 2021). This case was selected because the student expressed particular well-being challenges during the 6 months following the course. We examined this student’s CIT scores, interviews, journal entries, and final portfolio. This case study aims to demonstrate a holistic perspective through a mixed method of qualitative and quantitative data analysis (Yin, 2014).

Results

Participants

Eleven of 20 students in the Creativity and Well-being course participated in the study, completed the consent process, and took the CIT pre-survey. Ten students completed all data sets: CIT pre- and post-course surveys, post interview, and final interview 6 months later. The students (pseudonyms used below) ranged from first year to seniors.

Quantitative Analysis

The total CIT scores increased significantly from pre- to post-course (t9=2.34, p=0.044). Exploratory analyses of changes in CIT dimensions and subscales revealed that the strongest pre- to -post effects were within the Mastery dimension and the subscales: Skills (t9=4.31, p=0.002); Community (t9=3.16, p=0.012); Accomplishment (t9=2.75, p=0.002); Trust (t9=2.40, p=0.040). The student who was selected for a case study showed a particularly large change (more than twice that observed in the other students) for pre- to post-course in total CIT scores.

Qualitative Analysis of the Interviews

Eight themes emerged from analysis of the interviews: 1. self-acceptance and self-compassion, 2. valuing self-expression, 3. seeing others, 4. redefining creativity, 5. finding safe spaces, 6. recognizing negativity bias and character strengths, 7. reflecting on the past, 8. living in the present. Three themes are described below (see Appendix D).

Theme 1: Safe Spaces

Some students had difficulty describing a “safe space” in their artwork. One student said she did not have a safe space and drew an imaginary one. Another student depicted a space she considered safe at the beginning of the class, but not at the end. Learning that some students lacked a safe space heightened the importance of providing one within the course.

All instructors stressed creativity and imagination as keys to success in this course. This “judgment-free zone” allowed students to express themselves. Several participants said they felt acceptance and trust in the class community. Trust gained from discussing creative works helped students navigate experiences after the class with less concern about others’ judgments.

Theme 2: Redefining Creativity

Students learned about the creative process, creative mindset, and creative self-discovery. One student, Rena, explained how creativity became valuable for “navigating chaos” in her life, the theme of her final presentation. She said the works she presented “felt more intimate to me because I could go into my deeper memories and emotions.”

In post-course interviews, students described reconnecting with childhood creativity. Mariko said she once drew “pencil pictures,” but stopped by junior high, thinking she was not “good at that.” In the class, she could “express my safe place…on paper.” She “really felt a sense of satisfaction,” even though her picture “wasn’t good or sophisticated.” For Mariko, satisfaction was no longer dependent on proficiency, but on capturing emotion, using imagination, and immersing herself in the physical process of drawing. Before the class, Rena felt creativity was “a super difficult thing to achieve.” After the course, she understood that “a simple action like drawing is obviously creativity,” explaining that “everyone has creativity and like potential, we can grow those…no, I don’t want to say abilities, but [through] creativity, we can grow.”

Many students featured the collaborative visual art activity “Travel Together” in their final portfolio. A senior (Kumiko) shared that she had typically avoided collaboration, explaining that in recent art classes she made “her own art rather than communicating with others.” Through “Travel Together” however, she “felt…joy collaborating.” In her 6-month follow-up interview, Kumiko said the Creativity and Well-being class helped her feel “more relaxed” about “speaking up” in classes and presentations with others. Joining the university’s sign language club and creating a collaborative play in which “each person’s strengths and personalities were combined,” Kumiko said her strengths in the class coalesced with later creative activities.

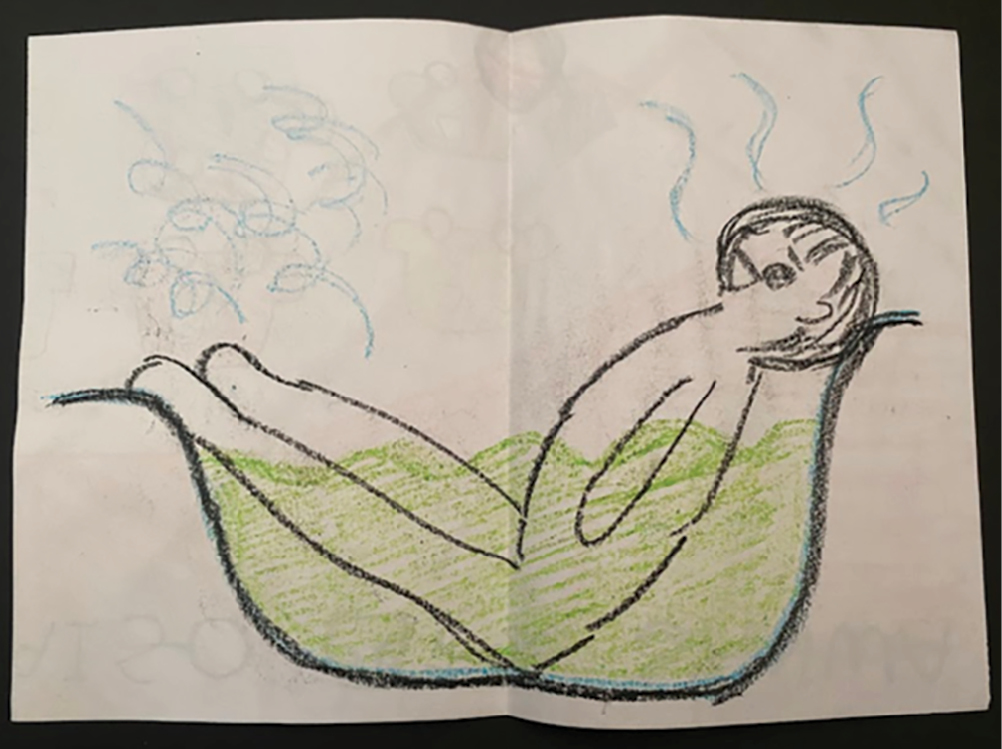

Theme 3: Self-acceptance and Self-compassion

Creativity was a conduit for self-acceptance. One student (Rie) said, “creativity helped with honesty, self-observation, and acceptance” (see Figure 3). She was “satisfied” with her three-dimensional self-portrait: two roses, one complete, the other broken. She did not see herself as a “creative person,” but created artwork to express and accept herself, “including the negative side…the fragile side inside.” She said, “I didn’t like expressing myself, so that was a really big challenge for me…I didn’t think it would work for me, but it did.” Having “art sense or not” did not matter to Rie: She could “think about” and “express” herself, and “that is more important.”

FIGURE 3 | Three-dimensional self-portrait.

As suggested, many students felt that they lacked the ability to express themselves before the class, claiming they were not “creative.” These preconceptions might be related to students’ inability to accept themselves as they are. One stated that after the course, she became capable of sharing her struggles with friends. Moving forward, she would be able to verbalize vulnerabilities and ask for help. Developing expressive confidence allowed students to better understand their experiences and feelings, eventually leading to self-acceptance. As another student put it, he was “able to learn how to express” his “creative, complex, and chaotic world to others, and share the interest, and also the joy of that.”

Case Study: A Thematic Profile of Saki

Saki was a graduating senior. Near the course’s beginning, Saki represented her past in a self-portrait as a starfish (Figure 4). The yellow barbs, she wrote, symbolized negative emotions: “I sometimes have an acrid feeling inside me.” The starfish’s ambiguous physical structure symbolized her own identity: “I’m not sure who I am. I’m not sure what makes me happy.”

FIGURE 4 | Three-dimensional self-portrait.

Saki had difficulty completing daily journal assignments; however, as noted, her overall CIT scores revealed significant growth in well-being. In particular, her increase on the subscore Meaning and Purpose was five times greater than the average.

At the follow-up interview, Saki shared that she had been unsuccessful in job-hunting, which was causing significant stress.

Thematic profile of Saki: Self-acceptance and self-compassion

Six months after the course, Saki continued practicing self-acceptance and compassion through the concept of negativity bias. Describing job-hunting, Saki said,

When I’m rejected…I sometimes feel like, ‘Oh, I’m a person who doesn’t have any good points and I sometimes blame myself, but I can remember from the class, I can change that. I keep in mind that the negative side is easy to see …it’s a negativity bias. I considered myself a little bit more, wondering, ‘Oh, am I okay?’ I might be not okay sometimes, but I feel that’s not a bad thing.

Saki’s summary of her emotions, “It’s okay to be not okay,” demonstrated persistence of self-acceptance and self-compassion when faced with emotional challenges 6 months after the class.

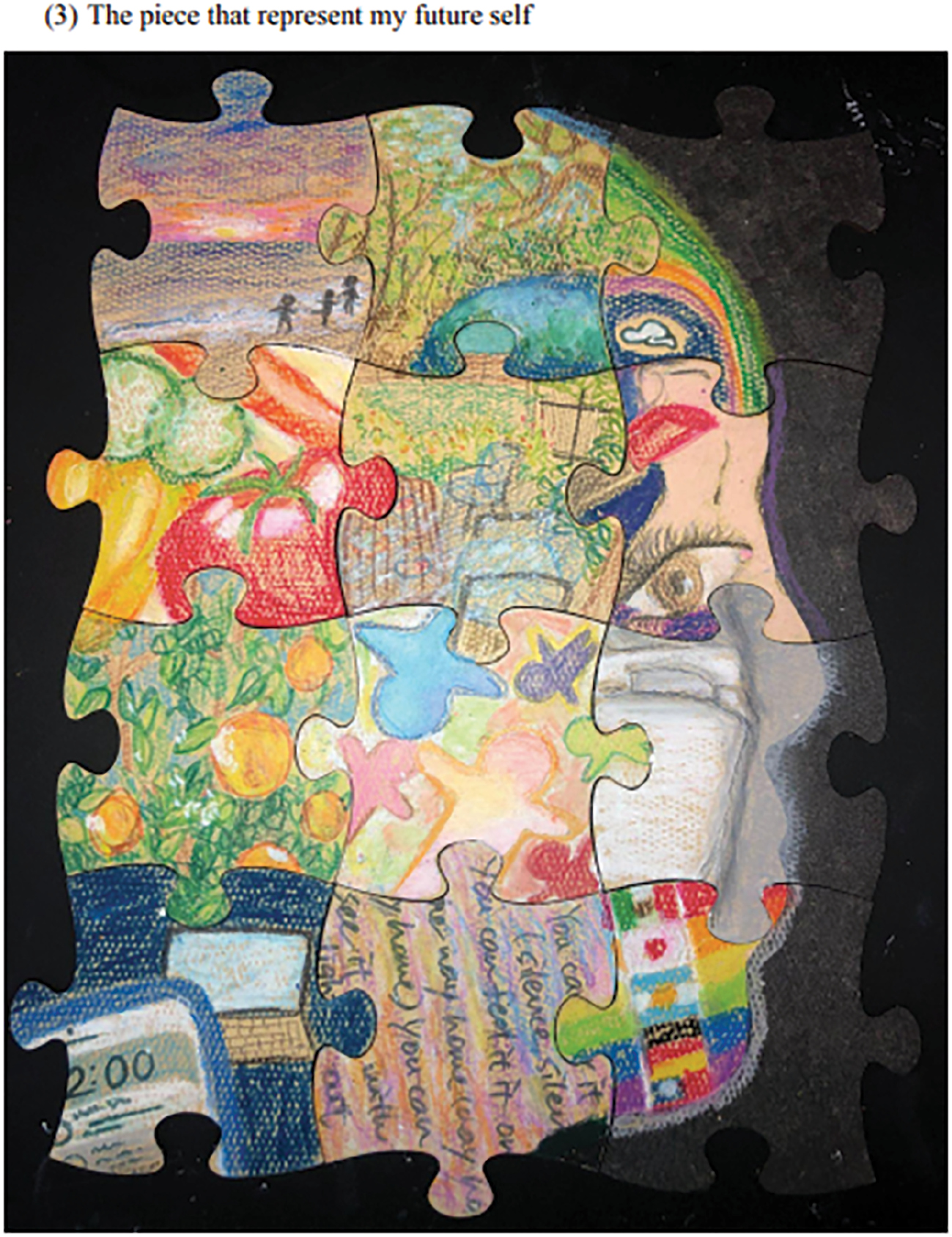

Thematic Profile of Saki: Finding a Safe Space

Saki also showed use of safe spaces in managing disappointments after the course. During the course, she represented her safe space as a bath (Figure 5). Six months later, she recreated this space using a technique she had learned in a drama exercise during the course, when students pretended their negative emotions were a T-shirt, and they acted out taking off the shirt. Saki said:

FIGURE 5 | Safe space drawing.

The day I got the email that I was rejected by a company, I was so disappointed, thinking that I am such a bad person. But I noticed it’s only…one company that I was rejected by. So I felt like I should change my mind, and I remembered the class. So before I took the bath, I changed clothes, and I thought that I was taking off my negative feeling, and then went to take a bath. And I was so relaxed.

Saki’s description of creating a safe space when facing emotional challenges demonstrated the persistence of safe space practices initiated during the course.

Thematic Profile of Saki: Redefining Creativity

A final theme for Saki was in redefining creative expression as a tool for self-actualization. In her puzzle (Figure 6), Saki considered the question, “What makes me, me?” One puzzle piece (above right) shows ascending steps representing visiting the Great Wall of China as a child with her aunt and mother. Wanting to rest, the older women suggested that Saki continue. Saki said, “When I went to a higher place, it was really far from my mom and my aunt, so I felt like I could do it for myself. I remembered this, and I feel like [I] am trusted.” In her portfolio, Saki wrote, “I remember my feelings [from] that time, and that unconsciously became one of my motivations for now.”

FIGURE 6 | Self-portrait puzzle and self-portrait puzzle detail.

Beginning with a starfish’ barbs representing destructive emotions, Saki ended the course using creativity to symbolize trust in herself and motivation for well-being. Seeking resolution to the problem raised by her earlier self-portrait as a starfish (“I’m not sure who I am. I’m not sure what makes me happy”), she later reflected about the puzzle-making activity, “What we learned helped me to find the puzzle of what makes me, and how to be happy.”

Saki’s case answers the question for this feasibility study about whether practicing creativity in tandem with positive psychology has a positive impact on students’ well-being. Her story demonstrates that 6 months later, as she faced emotional challenges, the course had a persistent positive effect in terms of accepting herself with compassion, utilizing a safe space, and redefining creativity as a tool for self-actualization. Saki’s case also illustrates that the interaction among selected themes can be synthesized in various ways, depending on students’ needs. Saki’s and other students’ use of terms such as “negativity bias” when referring to their well-being reflects the importance of integrating concepts of positive psychology into the course.

Discussion

Evidence of Positive Impact on Well-being

The study’s key finding suggests the Creativity and Well-being course had a positive impact on student well-being. CIT survey results revealed that students’ thriving increased after participating in the course. The study also suggests that creative engagement together with positive psychology may positively impact Japanese college students. Drawing from our qualitative results, the discussion below focuses on the three most salient themes emerging from student interviews: safe spaces, redefining creativity, and self-acceptance and self-compassion.

Theme 1: Safe Spaces

Creating a safe psychological space where students could explore well-being through non-goal-oriented creative activities was fundamental to the course’s success. To establish a safe, shared space, students became aware of unspoken rules underlying most Japanese classrooms, where students seek “correct answers” to teachers’ questions, blaming themselves if they cannot find them. Sharing creative ideas and decision-making was unfamiliar for students. This “transmission of knowledge” pedagogical approach shapes student belief that they should sit quietly without discussing their own ideas, limiting students’ agency and active learning. Most students feel rigid and inadequate in this judgmental “blank slate” banking educational environment (Freire, 2000).

Undoing years of “gap approach” education, students adopted new mindsets based upon their strengths. Compared with traditional school settings, this reverse approach initially astonished students. Letting go of expectations became a first step towards taking risks in their artwork. Although initially challenging, students welcomed working in a “judgment-free zone” focused on their strengths and on developing self-confidence and self-acceptance. Positive, caring interactions among students and teachers were observed in the everyday life of the class. Sharing creative ideas helped students’ anxiety gradually decrease, allowing room for imagination and new hope for their future self.

Theme 2: Redefining Creativity

Joy in art is greatly diminished by middle school, when confidence in creativity falters. Returning to creative activities in young adulthood helped students see that art did not have to be goal-oriented; rather, creativity became an organic process of navigating complexity, contradictions, and multiple views (Barron, 1969). As Rena confirmed, those who engage in creative processes can become “more intimate with themselves” (Kaufman & Gregoire, 2015). Many participants initially described discomfort expressing feelings, especially negative ones; yet in their interviews, students successfully articulated experiences of creativity, well-being, and emotions (negative and positive). Students became increasingly comfortable sharing feelings while describing their creative pieces, especially in small-group final presentations, which became an intimate space for mutual support.

The drama activity Zip especially enabled students to express negative emotions. Reinforced by positive psychology sessions on recognizing and expressing negative emotions, Zip offered an opening to say “no,” acknowledge that “it is okay not to be okay” (as Saki put it), and express emotions they might usually hide. Multiple participants said Zip helped them to become more honest about their feelings than previously.

Theme 3: Self-acceptance and Self-compassion

The course’s positive psychology sessions emphasized that it is natural to view negative events as more impactful than positive ones. Since Japanese culture discourages negativity toward others, it is often difficult to acknowledge negative emotions, even to oneself (Matsumura, 2019). Recognizing this negativity bias is a first step toward accepting negative mental states. Self-acceptance requires understanding one’s own strengths and weaknesses, which results in increasing self-worth (Shepard, 1979).

Self-compassion is another crucial element of student well-being. However, at the course’s beginning, self-blame for negative emotions was prevalent among students. Neff (2003) defines self-compassion as self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness. To highlight kindness to oneself, students learned from positive psychology that negative and positive emotions are both valuable (different from the goal of positive thinking). This principle, along with negativity bias, resonated with students initially skeptical about the concept of self-compassion.

Toward the end of the course, many students said they gained self-compassion through their use of creativity and peer collaboration in the safe space the course provided.

Limitations

Limitations include the small sample and lack of a comparison group. Future research is needed to further understand the impact of creativity on the well-being of Japanese students using larger samples and randomized control study designs.

Conclusion

This preliminary study explored quantitative and qualitative approaches to consider how creativity might enhance the well-being of Japanese college students. Total scores from the CIT reflected increased thriving among participants after taking the course. Interviews conducted after the course and 6 months later revealed that students readily synthesized information they received about positive psychology into how they discussed both their artwork and personal sense of well-being. Moreover, offering an avenue for further focus and study, the Creativity and Well-being course provided experiences that might help mitigate stigma about engaging in mental health treatments. The opportunity to interact with mental health professionals in the class allowed students to speak openly about their own mental health and life challenges, creating a safe experience that could provide scaffolding for a future willingness to seek help when needed (Masuda et al., 2007). This awareness is important not only to the students the Creativity and Well-being course serves, but to the communities they belong to now and in the future.

About the Authors

Lee Friederich (PhD) is a Professor in the International Liberal Arts program at Akita International University, specializing in Japanese Literature and Literature in English. Publishing on contemporary Japanese women poets in Japan and the United States, she has taught poetry in mental health institutions, prisons, women’s shelters, and in educational settings from elementary school to university in the United States. Her poetry has appeared in journals such as The Northwest Review and Denver Quarterly.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: lfriederich@aiu.ac.jp; Tel.: +81-70-2667-2768; Fax: 81-18-838-4343. ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5467-2764.

Yuko Taniguchi is an Assistant Professor of Medicine and Arts| Arts in Health at the Center for Learning Innovation at the University of Minnesota Rochester. She is also the author of a volume of poetry, Foreign Wife Elegy (2004), and a novel, The Ocean in the Closet (2007), both published by Coffee House Press. She regularly collaborates with artists and healthcare professionals to explore how creative activities lead to self-discovery and healing. ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0009-0004-1107-7991.

Naoko Araki (PhD) is a Professor at Akita International University in Japan. She teaches drama for communication, bilingual education, and English as a global language. Her career as an educational researcher focused on the use of embodied learning for communication and additional language education. Her long-standing research interest in interdisciplinary approaches has provided scholarly opportunities to theorise everyday language and cultural practices. Her recent work introduces drama pedagogy for well-being.

Naeko Naganuma is an Associate Professor of the English for Academic Purposes (EAP) program, also serving as Dean of Students, at Akita International University. Her research interests include integration of wellbeing education into curricula, student community building through experiences in theme-based on-campus residences, teaching reading and vocabulary with technology, and use of self-reflection in classrooms.

Joel Friederich is a creative writer and Professor in the International Liberal Arts Program at Akita International University in Japan. His published collections of poetry include Blue to Fill the Empty Heaven (Silverfish Review Press), Without Us, and The Body We Gather. His home is in northern Wisconsin where he is an emeritus professor at the University of Wisconsin - Eau Claire - Barron County.

Kathryn R. Cullen (MD) is a tenured Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Minnesota, where she directs the Division of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. She leads an NIH-funded research team examining the neurodevelopmental underpinnings of depression, self-injury and suicide risk in adolescents and young adults, and investigating interventions aimed at promoting healthy trajectories in these youth. ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9631-3770.

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

References

Abbing, A., Baars, E. W., de Sonneville, L., Ponstein, A. S., & Swaab, H. (2019, May). The effectiveness of art therapy for anxiety in adult women. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1203–1203. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01203.

American Art Therapy Association (AATA). (2024, May). https://arttherapy.org.

Ando, S., Yamaguchi, S., Aoki, Y., & Thornicroft, G. (2013). Review of mental-health-related stigma in Japan. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 67, 471–482.

Bachelard, G. (1958). The poetic of space. Beacon Press.

Barron, F. (1969). Creative person and creative process. McGill.

Baumeister, R., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323–370. DOI: 10.1037/1089-2680.5.4.323.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage Publications.

Cremin, T., & Chappell, K. (2021). Creative pedagogies: A systematic review. Research Papers in Education, 36, 299–331.

David, S., Boniwell, I., & Conley, A. A. (Eds.). (2014). Oxford handbook of happiness. Oxford University Press.

Dingle, G. A., Williams, E., Jetten, J., & Welch, J. (2017). Choir singing and creative writing enhance emotion regulation in adults with chronic mental health conditions. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(4), 443–457. DOI: 10.1111/bjc.12149.

Erbay Dalli, Ö., Bozkurt, C., & Yildirim, Y. (2023). The effectiveness of music interventions on stress response in intensive care patients. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 32(11–12), 2827–2845. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.16401.

Erricker, C., & Erricker, J. (Eds.). (2001). Meditation in schools: Calmer classrooms. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Fancourt, D., & Finn, S. (2019). What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? WHO Regional Office for Europe.

Fancourt, D., Perkins, R., Ascenso, S., Carvalho, L. A., Steptoe, A., & Williamon, A. (2016). Effects of group drumming interventions on anxiety, depression, social resilience and inflammatory immune response among mental health service users. PLoS One, 11(3), e0151136. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151136.

Frattaroli, J. (2006). Experimental disclosure and its moderators. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 823–865.

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum Intl Pub Group.

Fukuzawa, R. (1994). The path to adulthood according to Japanese middle schools. Journal of Japanese Studies, 20(1), 61–86. DOI: 10.2307/132784.

Gilroy, A. (2006). Art therapy, research and evidence-based practice. Sage Publications.

Gromada, A., Rees, G., & Chzhen, Y. (2020). Worlds of influence. UNICEF Office of Research. https://www.unicef.org/innocenti/media/1816/file/UNICEF-Report-Card-16-Worlds-of-Influence-EN.pdf.

Hemo, C., & Lev-Ari, L. (2015). Focus on your breathing: Does meditation help lower rumination and depressive symptoms? International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 15(3), 349–359.

Kaufman, S., & Gregoire, C. (2015). Wired to create. Perigee, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

Kimura, S. (2022). The largest number of truancy ever, securing a diverse learning place. NHK. https://www.nhk.or.jp/kaisetsu-blog/700/476069.html.

Koda, M., Harada, N., Eguchi, A., Nomura, S., & Ishida, Y. (2022). Reasons for suicide during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. JAMA Network Open, 5, e2145870.

Masuda, K., Suzumura, K., Beauchamp, K., Howells, G., & Clay, C. (2007). United States and Japanese college students’ attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. International Journal of Psychology, 40(3), 303–313. DOI: 10.1080/00207590444000339.

Matsumura, A. (2019). Sekai ni tsuyo suru kodomo no sodate kata [How to raise world-class children]. Tokyo: Wave Publisher.

Montt, G., & Borgonovi, F. (2018). Combining achievement and well-being in the assessment of education systems. Social Indicators Research, 138(1), 271–296. DOI: 10.1007/s11205-017-1644-y.

National Organization for Arts in Health (NOAH). (2024, May). https://thenoah.net.

Neff, K. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2, 85–101. DOI: 10.1080/15298860390129863.

O’Connor, P., & Gregorzewski, M. (2022). The intellectual whakapapa informing the New Zealand Drama Curriculum. Teachers and Curriculum, 22(1), 9–19. DOI: 10.15663/tandc.v22i1.415.

Pandian, A., Ling, C. L. C., Lin, D. T. A., Muniandy, J., Choo, L. B., & Hiang, T. C. (Eds.). (2014). Language teaching and learning: New dimensions and interventions. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Pennebaker, J., & Chung, C. (2011). Expressive writing. In S. Friedman (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of health psychology (pp. 417–437). Oxford University Press.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. (2004). Values in Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS) [Database record]. PsycTESTS.

Priya, A. (2021). Case study methodology of qualitative research. Sociological Bulletin, 70(1), 94–110. DOI: 10.1177/0038022920970318.

Rodriguez, A. K., Akram, S., Colverson, A. J., Hack, G., Golden, T. L., & Sonke, J. (2024). Arts engagement as a health behavior. Community Health Equity Research & Policy, 44(3), 315–322. DOI: 10.1177/2752535X231175072.

Shepard, L. A. (1979). Self-acceptance: The evaluative component of the self-concept construct. American Educational Research Journal, 16(2), 139–160. DOI: 10.2307/1162326.

Sorgente, A., Zambelli, M., Tagliabue, S., & Lanz, M. (2023). The comprehensive inventory of thriving: A systematic review of published validation studies and a replication study. Current Psychology, 42, 7920–7937. DOI: 10.1007/s12144-021-02065-z.

Su, R., Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2014). The development and validation of Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving (CIT) and Brief Inventory of Thriving (BIT). Applied Psychology Health and Well-Being, 6, 251–279. DOI: 10.1111/aphw.12027.

Takahashi, A., Tachikawa, H., Takayashiki, A., Maeno, T., Shiratori, Y., Matsuzaki, A., & Arai, T. (2023). Crisis-management, Anti-stigma, and Mental Health Literacy Program for University Students (CAMPUS): A preliminary evaluation of suicide prevention. F1000Research, 11, 498. DOI: 10.12688/f1000research.111002.2.

Tang, Y., Fu, F., Gao, H., Shen, L., Chi, I., & Bai, Z. (2019). Art therapy for anxiety, depression, and fatigue in females with breast cancer: A systematic review. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 37(1), 79–95. DOI: 10.1080/07347332.2018.1506855.

Umeda, S. (2016). Japan’s Basic Act on Suicide Prevention Amended. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2016-06-07/japan-basic-act-on-suicide-prevention-amended/.

Van Lith, T., & Spooner, H. (2018). Art therapy and arts in health: Identifying shared values but different goals using a framework analysis. Art Therapy, 35(2), 88–93. DOI: 10.1080/07421656.2018.1483161.

Yin, R. (2014). Case study research and applications (6th ed.). Sage Publications.

Yue, L., & Peng, J. (2022). Evaluation of expressive arts therapy on the resilience of University students in COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 7658. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph19137658.

Zarowski, B., Giokaris, D., & Green, O. (2024). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on university students’ mental health: A literature review. Cureus, 16(2), e54032. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.54032.

Appendix

APPENDIX A | Connections between Creativity and Well-being (From the Creative Mindset Session)

| Creative mindset (goal: to create) | Well-being (positive psychology) (goal: to feel better, well) |

|---|---|

| Curiosity | Becoming curious helps you to notice your environment/become aware |

| Bold and Uncomfortable | Becoming bold helps you to navigate stress or the unknown, which leads to growth |

| Playfulness | Becoming playful allows you to experience joy and the enjoyment of living |

| Sharing | Sharing helps you connect with others and become aware of the self through this connection |

| Suspend forming opinions | Suspending opinions leads to non-judgment, compassion for others and yourself |

APPENDIX B | The Seven Core Dimensions and 18 Unidimensional Facets of Thriving

| Seven core dimensions | 18 unidimensional facets |

|---|---|

| Relationship | Support |

| Community | |

| Trust | |

| Respect | |

| Loneliness | |

| Belonging | |

| Engagement Mastery | Flow |

| Skills | |

| Learning | |

| Accomplishment | |

| Self-Efficacy | |

| Self-Worth | |

| Autonomy | (Lack of) Control |

| Meaning | Meaning and Purpose |

| Optimism | Optimism |

| Subjective Well-Being | Life Satisfaction |

| Positive Emotions | |

| Negative Emotions |

From Sorgente, A., et al., 2023 (p. 1721).

APPENDIX C | Interview Questions.

| First Interview Questions |

|

| Recalling all the creative pieces and activities from this course, |

|

| Second Interview Questions (6 Months After First Interview) |

|

APPENDIX D | Themes and Definitions Emerging from the Interviews

| Theme | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Accepting the whole self with compassion | Recognizing and accepting various aspects of the self; feeling kind toward the self |

| 2 | Valuing self-expression | Recognizing the value of being seen by courageously sharing their feelings in public; appreciating hearing others’ self-expressions; recognizing that the practice of self-expression builds confidence |

| 3 | Seeing others | Getting to know their peers deeply on a personal level through creative expressions; developing empathic views and senses toward the community |

| 4 | Redefining creativity | Expanding understanding of creativity as more than a product of genius and recognizing creativity as skills that they already possess and use; connecting to the playful aspect of the creative process |

| 5 | Finding safe spaces | Recognizing personal “safe spaces”; seeing opportunities open up in various areas such as artwork, group discussions, and presentations; appreciating a “judgment-free zone” that focuses on the creative process and exploration as a central assessment of the course instead of the outcome of the products |

| 6 | Recognizing negativity bias and character strengths | Applying the content from mental health and psychology education; recognizing the presence of negativity bias in their own lives |

| 7 | Reflecting on the past | Nurturing the past-self through making sense of past struggles; gaining a deeper understanding of past experiences through historical, cultural, and societal contexts |

| 8 | Living in the present | Practicing mindfulness, and paying close attention to current moments |