FIGURE 1 | One of the dances from the fairytale.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2023) 9(2):120–142 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2023/9/13 |

A Review of the Creative Dialogues Project: Using Creative Arts Online during the COVID-19 Pandemic

创意对话项目回顾:在新冠疫情 (COVID-19) 大流行期间使用在线创意艺术

1Private Consultant, New Zealand

2Dance/Movement Therapist, China

3University of Auckland, New Zealand

Abstract

In this article, the authors review the Creative Dialogues project, which began in January 2020 as a response to the health crisis that was then emerging in China. The authors asked a group of creative arts therapists from China, Guam, and the USA to join them to develop arts-based collaborative improvisations using dance, art, creative writing/poetry, and fairytale-making about their experiences related to COVID-19 in an online setting. The project expanded to be international in scope as the virus spread and continued until November 2022. The authors reviewed the metaphors and verbal reflections created in these meetings. In this review, the authors identified five broad themes that included personal connection, confrontation of the unknown, conflict, resilience and hope, and spirituality. Examples of the themes are presented.

Keywords: creative arts, creative arts therapy, subjective experiences of the pandemic, improvisation

摘要

本文中,作者回顾了2020年1月开始的“创意对话”项目,以应对当时在中国出现的健康危机。作者邀请了一群来自中国、关岛和美国的创意艺术治疗师加入他们的行列,利用舞蹈、艺术、创意写作/诗歌和童话故事创作,在网络环境中讲述他们与 COVID-19 相关的经历,开发基于艺术的协作即兴创作。随着病毒的传播,该项目扩大到国际范围,并持续到 2022 年 11 月。作者回顾了这些会议中产生的隐喻和口头反思。在这篇回顾中,作者确定了五大主题,包括人际关系、对未知的对抗、冲突、韧性和希望以及灵性。介绍了主题的示例。

关键词: 创意艺术, 创意艺术疗法, 大流行病的主观体验, 即兴

Introduction

The Creative Dialogues project (Harvey et al., 2020a,b) began with the emergence of the COVID-19 health crisis in late January of 2020 and continued until November 2022. During this project, participants from 12 countries met online using Zoom and co-created arts-based improvisations to express their subjective experiences of the pandemic. A smaller number of members participated with regularity in most groups and formed a central core while other participants joined less frequently. The members used integrated dance, music, art, creative writing/poetry, and imaginative storytelling to develop metaphors in response to the verbal report members presented individually and in group verbal reflections of experiences they had during COVID-19. In this article, we review this material to investigate subjective experiences during this international crisis.

Development of the Project

The project started when the pandemic was beginning in China. The authors contacted each other to set up a session online among creative arts therapists in China, Guam, and New York City, USA. The improvisations were structured using the form of physical storytelling (PS) (Harvey & Kelly, 2016). In PS, a small group of dancers create improvisations in response to verbal reports while the other group members use their active imagination with spontaneous art and creative writing to contribute to these improvisations. Musicians joined the project during the initial stages and were able to attend many meetings as active partners. The intention of this collaboration was to create metaphors that expanded verbal reports to include multiple perspectives that included somatic, nonverbal, and emotional experience.

The results of the initial meeting were surprising as promising outcomes emerged. In a review of the material created during the improvisations and comments that followed, it was clear that emotional connection and empathy developed. The metaphors and verbal reflections of the improvisations suggested that the members were experiencing distress, fear of the virus, and social isolation. The arts-based improvisations also presented a sense of spirituality and connection among the participants through the experience of collaborative creativity despite the potential barriers of being from different countries and using an online platform (Harvey et al., 2020b).

As the pandemic spread though the world, the project expanded to include more countries and regions including Europe, North America, Oceania, and Asia. In all, there had been 45 participants from Guam, China, Italy, Switzerland, the Netherlands, UK, USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Germany, and Vietnam. Most were creative arts therapists. However, some had no experience with the arts. Forty-one Zoom meetings were held frequently from early 2020 to the beginning of 2021 and monthly afterward until November 2022 when the impact of the pandemic was lessening.

As the new events related to the pandemic developed such as surges in cases, increases in deaths, social restrictions, and protests of the health-related rules in different regions of the world, the subjective experiences of our participants’ experiences also changed (Harvey et al., 2020a). The metaphors and form of improvisations evolved alongside these changes.

Other Arts-based Projects that Emerged during the Pandemic

A group of researchers in the UK (Bradbury et al., 2021) conducted a review of published work related to the role of the arts during the first year of the health crisis. Their findings suggested a complex picture in which some pre-pandemic arts activities such as performance became more restricted while other informal activities such as home-based and online projects emerged unexpectedly and increased in response to the social restrictions. The general outcomes from this literature also suggested increases in social connection among those who engaged in these alternative uses. There were also reported increases in coping, especially in mental health contexts as participants were able to use arts-based action to help them cope with pandemic-related stress. The authors suggest that these developments point to a possibility of a more flexible use of the arts in helping address future emotional stress.

An illustration of this process occurred in one small city in New Zealand. The owners of an art gallery developed a project when the lockdowns initially occurred in which they invited the artists associated with them to use this period to create artwork and share it with them. The artists contributed verbal descriptions of the experiences of being at home alongside the art they produced for the gallery. The owners self-published this material in a book. The gallery later had a public showing of the art in the gallery when the lockdown ended in their community (Gover St. Gallery staff, 2020). Most of the artists described positive experiences of having time to engage in their creativity more completely.

Monica Re, a dance therapist, described a project she developed in a city in Northern Italy using both online and in-person action to engage groups in her community in creative projects together (Re, 2023). The goal of these expressive activities was to offer an alternative to inaction that was leading to isolation and stress within the community she interacted with. The groups included young children, adolescents, and elderly people. In the initial phase, groups of school children and elderly living in care facilities made dance and artistic costume designs to create animals while online during the beginning of the lockdown in their region. The groups were then able to share their creations with each other using the Internet. As the restrictions were being relaxed, Re used a combination of in-person and online resources to develop a community-wide project addressing the emotional responses to COVID-19 using both dance and storytelling with these groups. Re observed that the groups were engaged in their collaborations together and communicated positive feeling states together.

Focus of this Review

The goal of the current article is to review the metaphors generated during this project to gain an understanding of subjective experience, emotional climate, and how this changed over the time of the crisis. Given the amount of improvisational material, the authors decided to review sessions from the beginning, middle, and end of the project and reflections the groups offered during these sessions. They also reviewed the improvised summary fairytales that were co-created by group members at end of each session. The fairytale is a form from PS in which participants improvise a verbal fairytale in collaboration with dance/music improvisation with no preset text or end point. In our project, the fairytale was used in the groups as a summary of the arts-based material as well as the verbal reflections of this material that emerged during the session (Harvey & Kelly, 2018).

This material was available in recorded videos of all the sessions. The participants gave their permission prior to their participation. Participants also gave their permission for any use of their participation in public presentation and use in future publication with the understanding they could withdraw their permission at any time. This applies to all the material used in the current review article.

The Sessions

The meetings did not have a standardized format, and the structures evolved during the pandemic to respond to the changing situations of the group. The improvisations did develop some variations. For example, some dance/music improvisations were not always followed with art/poetry/creative writing but led to another dance or music episode. On other occasions, meetings began with duets between musicians from different regions of the world rather than dance. Toward the end of the project, fairytales were told in different languages together to match the primary languages of the participants. However, the meetings did follow the general format of beginning with a verbal report from each member about their recent experiences with the health crisis that was followed by a series of arts-based collaborative expressions to express personal experiences that were beyond words. Group members then added verbal reflection of the arts-based episodes.

The sessions always ended with an improvised fairytale in which one or two group members improvised imaginative storytelling along with the dance/music. This form used all the modalities available in that session including, dance/music and storytelling created together simultaneously. The story format gave the expression an organized imaginative narrative. This form was used as a summary of the overall session during each meeting. Some fairytales were co-created using two languages. These multilingual stories were translated during the verbal reflection discussion at the end of the meeting.

In this review, the authors looked at each improvised episode as a separate metaphor that included some combination of arts-based expression and verbal reflections. These metaphors were assumed to express members’ complex experiences that included verbal reflection as well as nonverbal, emotional, and somatic aspects. This use of reviewing both verbal and expressions representing a beyond words aspect was to facilitate an integration of these expressions.

The authors then compared each of the metaphors with other episodes from the beginning, middle, and end of the project. Metaphors that expressed similar aspects were considered to represent broad themes. As the fairytales were summaries of the meetings, the comparisons of fairytales were central in this review.

The broad themes that emerged after a review of the Zoom meetings included the social/emotional connection that developed through active participation in co-creative expression, the confrontation of the unknown, the emergence of social conflicts, the development of resilience and hope, and the experience of spirituality. The authors also noticed that the metaphors became increasingly complex over the time of the crisis as social events such as conflict and protest and increases of death and isolation emerged. In our review, the themes of the unknown and personal connection were especially prominent, influencing most sessions.

The broad themes will be presented using the metaphors and fairytales that illustrate the expressive content and intent of these themes. We will include a combination of pictures from some of the dance improvisations, artwork, poetry/creative writing, and verbal reflections from these metaphors to animate each main theme. This material will be presented alongside material from earlier articles about this project (Harvey et al., 2020b; Harvey & Wang, 2022; Mochi et al., 2022) to compare the development and change of these expressions as the project unfolded over time. The earlier articles will be included in the presentations of the themes of personal connection, conflict, and spirituality.

Themes

Table 1 outlines the figures, brief descriptions of the metaphors and fairytales, participants, and timeline of sessions related to these themes.

TABLE 1 | Figures, Description, Session Dates, Theme, and Participants

| Figures | Description | Date | Theme | Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

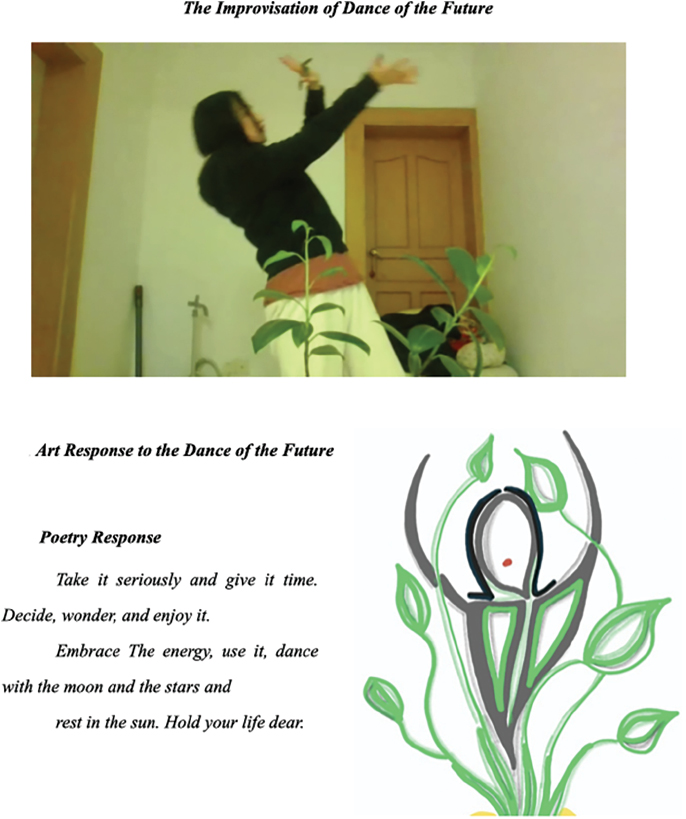

| Figure 1 | From a fairytale that illustrates connection across the online platform | July 2020 | Connection | Guam, China, USA |

| Figure 2 | From a solo dance about the anxiety of what the crisis will bring | March 2020 | The unknown | Guam, Italy, Switzerland, USA, China |

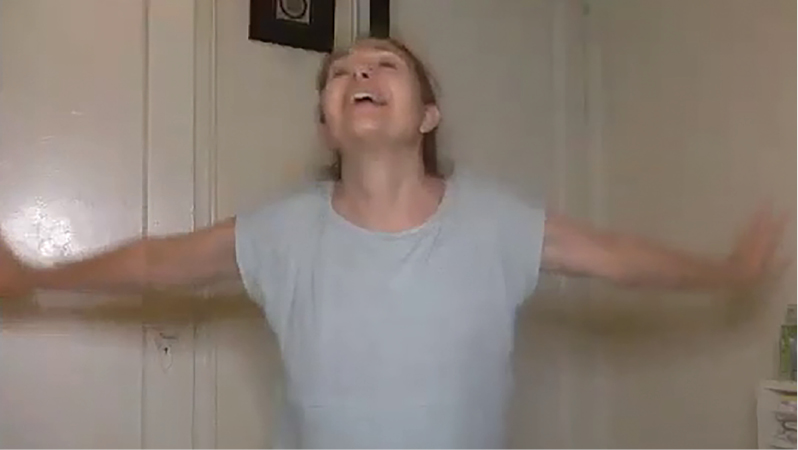

| Figure 3 | From a solo dance of dread and art and poetry responses to the solo dance. Fourth picture from the fairytale in this session | March 2020 (same session as the one above) | The unknown | Guam, Italy, Switzerland, USA, China |

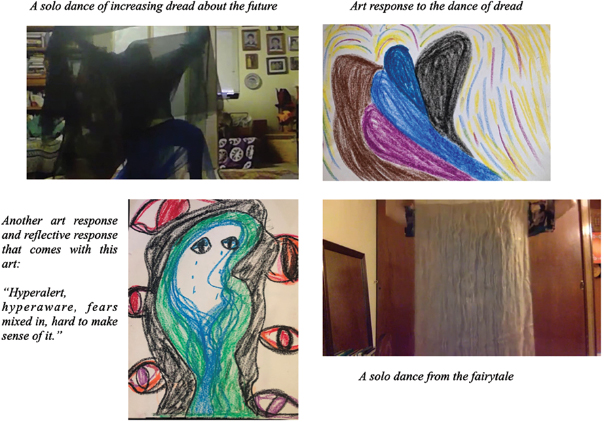

| Figure 4 | From a dance about issues around wearing masks | October 2021 | The unknown | Guam, China, Canada, New Zealand |

| Figure 5 | Pictures are from dances in response to protests and ongoing conflict | February 2021 and January 2022 | Conflict | USA, Guam, China, Switzerland, and New Zealand/Guam, USA, China |

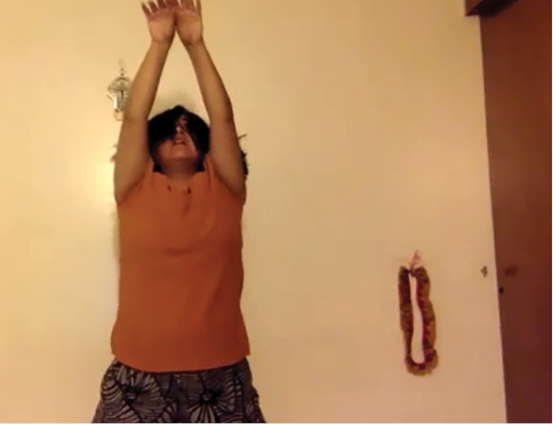

| Figure 6 | Dance of the future and poetic response | February 2022 | Resilience and hope | Switzerland, Italy Guam, China, New Zealand |

| Figure 7 | Beginning and end of the fairytale of hope | July 2022 | Resilience and hope | China, USA, Guam |

| Figure 8 | Art of the storyteller who presented the story of thankfulness | April 2020 | Spirituality | China, USA, Guam |

| Figure 9 | Art in response to the story of thankfulness | April 2020 (same session as the one above) | Spirituality | China, USA, Guam |

| Figure 10 | From the end of the fairytale that answered to the initial uncertainty and worry | July 2022 | Spirituality | USA, Guam, China, New Zealand, Canada |

Personal Connections

Harvey and Wang (2022) reviewed two meetings from the project 4 months apart using an arts-based inquiry that included a selection of the improvisations and the participants’ verbal reflection of their experiences using creative collaboration with each other in the online context. These meetings were conducted in April and June 2020 and included participants from Guam, China, Australia, and the USA. In this article, the authors describe how the participants reported that even using Zoom, they experienced a personal closeness with each other despite addressing the current news reports related to the rising political tensions between the East and West concerning COVID-19. This closeness included physical/somatic, emotional, and attunement experiences with each other that were largely nonverbal. The metaphors the group co-created in their improvisations had a theme of emotional closeness.

During a meeting in July 2020 that evoked a similar significant expression of personal closeness, a separate set of participants from Guam, China, and the USA began by describing experiences of being isolated, and feeling the impacts of social conflict, and the political tensions between the East and West. China and the USA had recently closed a diplomatic consulate in each other’s countries. Rather than addressing these political and social developments directly, the participants created two dance/music improvisations that were almost totally nonverbal. The movement in both dances included a great deal of synchronous movement among all the dancers. The musicians reported that they were both leading and following each other as well as the movers. The second improvisation ended with the dancers placing their scarves to their camera as if each could reach through the screen to grasp and join with the members from the other country.

Audience/witnesses responses included how trusting they felt from the very beginning. One dancer said she felt connected from the initial musical note she heard, and this feeling continued to deepen as her dance developed. One audience/witness noted that during the feeling of this connection within the experience of the improvisation, the boundaries of countries were not present. Another said that she felt close even though they were many miles apart. Others mentioned that this improvisation had created a language using the arts where they could all speak together about their feelings. A woman added that she loved speaking this arts-based language because it helped her feel connected not only to the group members but with the larger community on a global stage. At end of the session, this personal closeness had a quality of openness, spontaneity, and a presence in which all group members reported they shared together.

A Creative Writing/Poetry Response

Alone in a box/in a room, in an apartment/in a city/I can see you/can you see me?/But I can’t touch you/I don’t know if you can see me/How shall I capture your attention/how shall I woo you/capture your heart? To invite you into my city/into my apartment/my room/my box/We can dance you and I/and aloneness will be dispelled.

The session ended with two musicians/three dancers, and two storytellers all improvising together following each other’s expressions without a set agenda or end point to create a fairytale.

Fairytale of Calling

In the warm ocean water/flowing under the sun

A calling comes down through the mountains/through the sun/through the sea/through the ocean/a calling of sound.

A calling that sustains through time

A calling across all the lands/every single one/all of them/can you hear it?

The calling comes now/from the inside/from the inside out/yes, I hear it/yes, I feel it.

She sings and the silence is forever broken.

Yes/I hear it/yes/I hear it yes.

Yes, yes yes yes/none of this is for nothing/nothing is in vain/It is now and forever/it is now and forever.

Figure 1 shows a quality of openness that emerged during the expressions of connections during this improvisation. This connection did develop different qualities as the crisis continued along with the social protests and surges in cases and death rates. However, in each group, members reported they continued to feel a strong social/emotional connection with each other even as their improvisations began to reflect the emotional tensions that were emerging as the pandemic wore on. During the reflection throughout the project, participants reported that this connection helped them develop improvisation that expressed more divisive topics. The topic of an unknown future emerged as the pandemic began and will be presented in the next section.

FIGURE 1 | One of the dances from the fairytale.

The Unknown

In the beginning of the project, we used the form of having one member tell a story of their personal experience and then select a member from another country to improvise the dance in response to facilitate empathy with each other. Our second meeting was in early March 2020 as COVID-19 was spreading through Northern Italy and prior to effective social health restrictions being in place in that country. Two members were from Italy and Switzerland, three were from Guam, and one was from China. The Europeans initially presented events in which they described that they felt disoriented by the increases of the sudden health threat in their region and a fear of the future. These stories led to solo improvisations and artwork/creative writing followed by a fairytale. The metaphors that emerged were related to a confrontation with feelings about the unknown future of what the crisis might bring.

The Initial Dance Improvisation of Unexcepted Change with Strong and Varied Feeling

The ending gesture of the initial solo is shown in Figure 2. The dancer reported that she discovered this end point and experienced clarity from her improvisation only after dancing with multiple movement qualities and a variety of strong emotional expressions. The group members reported that this dance be called The Awakening, as they all needed to confront crisis.

FIGURE 2 | A solo dance about the anxiety of what the crisis will bring.

One Member’s Creative Writing in Response to the Dance of Awakening

I’m carrying a burden, I feel imprisoned and blind, I am not sure, but I will keep going.

It scares me but I am a fighter. I am tired of fighting at times.

I don’t want to fight no more.

It is time to wake up.

A second dance improvisation followed in response to a story from a participant as she described a feeling of increasing dread and anxiety from her sense of the beginning of crisis in Europe.

The Summary Fairytale

Where am I? I can be close. I can go up and down. I can fly and I can swim.

Where am I? It seems that I am going somewhere unfamiliar.

Am I alone? Who is here with me? Hello?

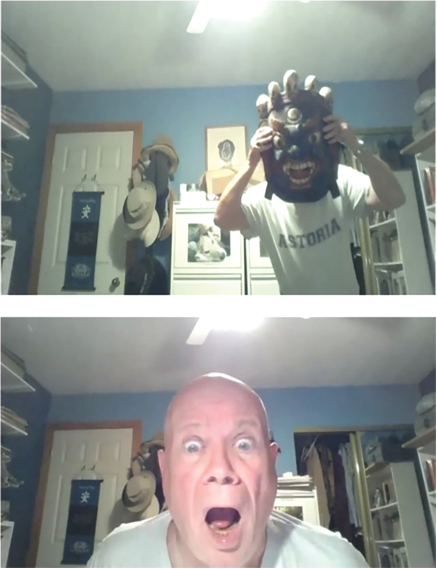

In Figure 3, the arts-based expressions point to a variety of emotional responses to this unknown future including anxiety, hypervigilance, and fear alongside a need to face the crisis and find meaning in this experience. This theme of relating to the unknown in a complex manner continued throughout the project. The use of a veil to express the unknown presence of multiple threats and the need to look behind it was repeated in a variety of ways. Figure 4 shows the picture from a session in October 2021 with members from New Zealand, Guam, China, and Canada. During this period, protests in countries from the West about wearing masks increased. This solo improvisation began with a man using a mask and then taking it off.

FIGURE 3 | Pictures and artwork from the fear of the unknown.

FIGURE 4 | Who are we behind the masks?

A Dance of Mask Wearing

The group discussed the feeling of vulnerability and the identity confusion that occurs when we stop wearing masks—including our social masks while living with the dual threat of the virus and the confrontations within our communities whatever our mask-wearing behavior might be.

During the middle of the project, this theme of a confrontation with the unknown changed from an emphasis on the possible dangerous impacts of COVID-19 to experiences of social conflict within communities. The theme of conflict will be reviewed in the next section.

Conflict

Mochi et al. (2022) describe the impact that the social protests had on group members and the how the metaphors that were co-created were influenced by these protests during the summer of 2021. This chapter presents a situation in which some of the group members who worked in health and education sectors reported their experiences when they became specifically targeted by the protests while following their professional roles during the enactment of health-related guidance. During a fairytale from July 2021 that included participants from Switzerland, Italy, China, and Guam, the teller improvised a fairytale of travelers being caught and separated in a sandstorm they could not escape and having to find each other in almost complete darkness.

In other sessions, there were different outcomes within the improvisations about the social conflicts. Figure 5 presents three illustrations from meetings completed in the late fall of 2021 and early winter of 2022. Participants were from China, Guam, the USA, and New Zealand. The sessions began with a verbal description of the group members’ experience of the multiple tensions within their communities related to the social restrictions alongside the surges of COVID-19 that were emerging at the time in their respective countries. Two of these pictures in this figure are from dance/music improvisations in response to the general emotional climate based on the somatic sense these participants had of from these descriptions. In another meeting, one participant told an account of how she felt abandoned by social and political leaders as the conflicts around COVID-19 and threat of serious illness intensified. The last picture is from a dance expression of this verbal report. The audience responded to these dances with spontaneous writing and poetry.

FIGURE 5 | Different outcomes in improvisations to conflicts.

Dances of Conflict

Poetic Response to Abandonment

Searching for connection/In the dark, I am lost.

I am crying and my face is swollen/I am afraid for myself.

To acknowledge my pain/My body is shaking.

From carrying the weight of the unknown

Where are you, my friends?/My people? I am praying.

I am searching.

Another Creative Writing Response to the Conflict

You pushed me. I find my centre. My strength my balance. You are with me each step of the way. I find my desire to fight which saves me.

In the final phase of the project, another group member provided this response to the long and ongoing conflicts that had split her community.

Another Creative Writing/Poetry Response

Bursts of energy—exhaustion

Bursts of Hope—exhaustion

Bursts of wonder—exhaustion

During each session in which the conflict theme emerged in the improvisation, the group acknowledged the personal sense of connection that developed within the group during their joint creative process even when the metaphors expressed estrangement and aggression in some form. This connection will be elaborated in the next section on the emergence of resilience despite the complex interpersonal challenges alongside the possibility of the uncontrolled spread of illness.

Resilience and Hope

The theme of hope developed throughout the project and became more prominent in our third year particularly as the social responses to the crisis became more pronounced and divisive. The following series of improvisations included a solo dance, art/poetry response (see Figure 6), and the fairytale of “The Forest of Hope” was from February 2022. The group members were from Switzerland, Italy, Guam, New Zealand, and China. This session was during a period of a new surge of cases coupled with a rise of social conflicts. Members mentioned the presence of their personal positive connection with others in the group as the session began and how this led to images of hope in the “Storm.”

FIGURE 6 | The dance of the future and art and poetry response.

A Creative Writing Response to the Initial Image of the Storm

The leaf on the branch in disbelief is shaken by the storm.

The cold wind is impetuous. The wind appears too strong also for the tree.

It shall pass says the leaf to herself, no it won’t she added discouraged.

Closed into herself the leaf hung tight to the branch while the storm seemed to soften.

These comments led to a solo improvisation around the theme of the future.

A Dance Solo of the Future

The Forest of Hope

This is a story of a tree, of wind, of leaves, and of a storm—a cold wind in a storm

“How do I handle the storm?” asked the tree.

“First you don’t stick your branch out like that/you kind of bring it back in and then where are your roots? Where are you roots?”

What good ideas! Said the tree.

“Do you feel others helping you under there? Giving you some strength?”

The roots grew and grew/and reached into the earth.

Spreading out under the soil/spreading out under the oceans/spreading out across the whole world to feel and hold onto the earth.

“Hold on Hold on!” “Give a little shimmy!” “You can shimmy with the wind little tree.”

Of course, there is the question of the leaves/The growing part and the wind again.

Well, some of the leaves are meant to be there and some of them are meant to move on/go elsewhere.

All the other trees leaned in and watched.

“That’s it little tree/shimmy with the wind/got your roots got your leaves.”

The forest became very proud of the special tree as she began to move and move throughout the clearing.

“Welcome to the forest/Welcome to forest life. Welcome to the storm in the forest we manage, we are together.”

Welcome to the forest of hope.

Another illustration of resilience emerged in a fairytale from a meeting in June 2022. In this meeting, almost half of the invitees were unable to attend, as they had unexpectedly become ill from COVID-19. Those who were able to attend were from Guam, China, and Germany. After the initial verbal check-in, participants developed improvisations around the theme of weariness, the influence of the absence of the other members who had developed the illness, and the long ongoing nature of the pandemic. The fairytale included a solo dancer, one teller, and a singer. Figure 7 shows the beginning and end of this improvisation.

FIGURE 7 | The beginning and end of the solo dance.

Fairytale of Hope

In the hall of the Gods and Goddesses/She is still there after everyone had left. They could say “This is it/I am done—I have finished my job/I no longer have the spirit of rulership to be here.”

But she stayed.

Someone must stay/what about the children/what about those who have been forgotten/I must find some strength/I must find my way/even though I am blind/even though I am infirm/even though I have not strength. I must have strength.

There is a reason for my presence/there is meaning in my breath.

I look around/I feel the air around me/I feel the water/the clouds/the sunshine/and I know There is the entire world to move forward.

And everyone/most everyone/many/have gone.

And I am here.

Dance of Hope

The group members who did attend the meeting noted that this fairytale fit with their situations, as they felt they were unable to leave their work, family, or community situations. The members acknowledged that this effort came at a personal emotional cost for them, as their employers, community, and political leaders work did not appreciate or support the complexity and difficulty of their experience. However, they felt their commitments to their community responsibilities remained of value to themselves.

Another response that emerged in our project related to spirituality. This theme will be reviewed next.

Spirituality

The connection with spirituality came in various forms beginning as early as the first meeting in February 2020 with participants from China, Guam, and the USA (Harvey et al., 2020b). In a summary fairytale during this session, “a very able god-goddess appears” when “the sky and earth is not yet separated.” One group member described the “sky and earth as a chaotic whole” and included a direct quote from the Tao De Jing, “The Tao breaks giving birth to one…Three gives birth to all things,” both alluding to Chinese spirituality.

Harvey and Wang (2022) present a verbal report and dance improvisation from a session after the virus had recently spread to other parts of the world. The session occurred in April 2020. In their article, these authors described a strong connection among members that developed from Australia, the USA, Europe, Guam, and China. This episode also included a series of metaphorical exchanges that spontaneously expressed a shared spirituality. This spirituality was not included in the previous article. It will be elaborated in this review.

A woman from USA told a story of feeling a deep appreciation for a store worker who had helped her obtain and buy food during a strict lockdown in her region. Part of this story was the sense that this store worker was unseen by the public despite her key role in helping others. The woman who told this story then selected a woman from China to develop a dance improvisation. Both women then used art and verbal reflections to express their personal experience related to this improvisation (see Figures 8 and 9).

FIGURE 8 | Art of the initial storyteller who presented the story of thankfulness.

FIGURE 9 | The humans and the nature are all in my heart.

The Initial Teller’s Art Following the Dance of Thankfulness

Storyteller’s Reflection and Metaphor Extension after the Dance and Art

The shape of the eye looking out reminded me of a bird flying in and looking out with compassion. The red is the heart center, and the purple on the outside is like a spiritual encasing that I was hoping for. And the yellow energy of enlightenment. All this energy swirling and needing to come out. But also, to me it’s the eye, seeing, wanting to see, and wanting to convey what’s seen. Or contain what it has seen. The circle (that is drawn) is like a mandala. For me, the image that was so strong was of a native American Shaman. I love that the Chinese woman was dancing my Native American Shaman.

The Dancer’s Artwork and Metaphor Development

The dancer reported that she also felt the spiritual aspect in her dance, the artwork, and in the sharing of with the storyteller.

In later sessions of the project, connections with spirituality came through fairytales in various forms. Sometimes, the fairy tellers had fairies, gods and goddesses, and animals speak in the voices of characters within the fairytale. This metaphorical speaking process was illustrated in a session in June 2020 during one of moments of tension between the USA and China that included violence toward Asians in the USA. The participants in this meeting were from Guam, the USA, Australia, and China. This session began with a verbal presentation of fear about the images in one’s own mind. As the session progressed, an underlying fear, ambivalence, and hopelessness emerged. An improvisation of two musicians deepened the experience and opened space for something new to emerge.

In the fairytale that followed the duet of the musicians, the tellers introduced a transformation in the story metaphor. The spiritual world spoke through fairies and broke the “silence, like a big cloud, descending” and provided guidance. “If we would only listen, if we could only feel in our bodies, everything around us, and we would be guided, the fairies say. And they felt it. And they were guided.” The fairies then became the dancers who “love to dance” and felt “beautiful” when they danced. The fairytale came to an end as “the music and sound in their own heart covered their skin, covered their touch, moved through them, as if it were a stream of water and light.”

Another session in July 2022 started with participants initially presenting verbal reports of uncertainty and worry. The initial dance and poetry improvisations reflected these feelings.

Poetic Responses Following the Initial Dance Improvisation

I am alive! I am alive! I am free!

But am I?

Death sneers in the shadows with a sardonic chuckle (heh, heh, heh, heh…!)

Am I always between death and life?

Searching for answers, I dance

In the core of my being, being born and dying every minute.

In this curious, Mysterious world

Another Poetic Response

Loneliness, yelling, breaking out—why? Why not? I miss the place where I used to be. Can we return? Can we just be here and now? You are with me. I am with you.

In the fairytale that followed included a dance/music improvisation with three dancers and two musicians, and two fairy tellers, the people’s questions are heard.

The village of gods and goddesses watching this knew that something would influence her, and she would change. Something would happen, but they didn’t know what. So, they wait, and wait, and wait. And the people, and the animals, and the fish, and the whales of course they were influenced—how could they not be? Something important had happened to them.

Then, a fairy teller describes how the people are transported to a new world.

Initially, the people are tentative about moving around in this new world. After all the jungles had been torn down. The ferns were gone. All the trails are wiped out and led in strange and mysterious ways to places no one had ever seen before.

As the fairytale came to an end, the other teller added that a spiritual knowing comes to the dancing figure that somehow, she knows she is on the right track (see Figure 10).

FIGURE 10 | The end of the fairytale.

Without finding the final answer of where she is going, she knows that her questions have been heard. And echoed and echoed throughout the stars.

Picture of the Dance of Spiritual Knowing

After the fairytale, dances, and music ended, one of the storytellers shared that he trusted that the flow was going somewhere. The other storyteller shared that she felt “the fairytale, movement, and music really went together and completed something.” A dancer shared that through dancing she felt that “the earth has really suffered in the past few years.” Another dancer shared that when she heard that the gods and goddesses did not know what would happen, “In my own story, the gods and goddesses were not the ones in control. And that for me was very powerful and very freeing.” These feelings of satisfaction, completeness, compassion, power, and freedom transformed the initial uncertainty and worry.

The importance of personal connection that developed throughout the length of the pandemic reemerged at the end of this part of our project. This will be reviewed in the next section.

A Fairytale of Goodbye

The final meeting of this review was in late November 2022. The members were from Switzerland, Italy, Guam, and New Zealand. All had attended several of the sessions, and many had participated in the initial sessions almost 3 years previously. The final fairytale included two dancers and two tellers. The fairytale was presented in two languages, English and Italian, as the tellers took turns responding to the dance duet. Not all members shared the same primary language.

A Fairytale of Farewell

The women woke up and left the house that morning with no

particular place to go. Today there are swallows, leaves, and wind.

They walked down the streets of the village through the flowers the

gardens, the narrow streets approaching the shore of the lake, the great lake.

Who knows what to expect today/There are beautiful glows of light

on the lake.

Before they were even aware they were in the lake immersed in the

bluest of the water.

We did well, it was worth it. It was quite a trip, now I am enjoying it.

As they swam, they could feel their bodies transforming, again and

again, again and again, until they were out of the water and flying and flying.

What a sense of lightness and delight. It was tiresome but

breathing this fresh air, I feel it was worth it.

Bye, see you soon,

They were preparing to say goodbye and leave their home and

their village and transform again into mysterious beings.

Bye, we will meet in another adventure. I will bring you with me in what I learned.

At this point, the villagers were out searching in the sky for them

waving their goodbye wishing them well feeling the sorrow of

missing them and the excitement of change.

Goodbye goodbye/and the sky opened and took them away to another world.

The group said that this final fairytale had a sense of optimism and adventure to it even though previous session had included tension about the future path of the crisis. All the members added reflections of the value they experienced in sharing creative moments with each other over the many meetings they had together. They also discussed how they had become close friends over this time in the online forum and being from diverse regions of the world.

Reflections

The Creative Dialogues project began as an experiment to see if arts-based improvisations could develop in an online forum among colleagues in China, Guam, and the USA, given the cultural and language diversity and an unfamiliarity with using the Internet for spontaneous creative communication. After some success, the process developed internationally as the virus spread. We found that that we could create an alternative communication with each other using art forms to make metaphors together that were meaningful concerning our emotional and nonverbal experiences.

As the crisis continued, our forms of improvisation evolved. We began by having individual members verbally present a personal experience related to the crisis and then select a person from another country to improvise dance to that report to facilitate empathy. As the pandemic spread, our “language” of improvisation became more complex. We introduced a practice of using ensemble dance/music/art improvisation to create nonverbal metaphors that could express a more general feeling or climate of the crisis the group members were experiencing during the time frame of the current meeting. Members’ comments indicated that this form offered an important view of their experiences as a group. We created summary fairytales that helped structure the metaphors of the sessions in imaginary storytelling.

Social connection clearly was important throughout each meeting of our project in its entirety. However, the quality of spontaneous openness from the initial phases of the crisis developed into other more complex feeling states when the group was influenced by experiences with conflict, themes of spirituality, and confrontations with the unknown. At one point, almost 2 years after we began, the metaphors about connection included dancers moving through a dust storm with almost no light to guide them toward each other. In this same way, the confrontation with the unknown began with a hesitance, disorientation, and fearfulness related to the crisis with questions of what was hidden. These questions developed into an open expression of vulnerability and even hope, as the metaphors began to include a look behind the mask/and veil and into the future. The metaphors that showed experiences of conflict also had several aspects over the years including a fear of showing oneself, of our own thoughts, experiences of abandonment and feeling of being alone, exhaustion, and the showing of confrontation. The sense of hope and resilience was expressed in a way that included joining with others as well as being shown with expressions of self-determination. The metaphors related to spirituality were an important aspect of the sessions. These spiritual expressions contained a combination of connection, the unknown, conflict, and resilience that often resolved the tensions among these polarities we had initially reported in the beginning of our meetings.

Final Thoughts

Arts-based activities can contribute to major crisis events on a community and international stage. The improvisations we reviewed provided a view of a wide variety of subjective experiences that are often unacknowledged in verbal reports. This depth and complexity of the emotional experience can remain unknown in verbal reports, especially in diverse cultural and linguistic international settings. These collaborative improvisations created an extraordinary communication that assisted in developing experiences that became beyond words among our group members.

After the final fairytale of goodbye, group members reported they had a sense of optimism and having had a special adventure in the long time they had developed collaborations together. There is reference to having had a meaningful experience in the process of creating an important time. In this review we have attempted to describe separate aspects of these sessions. However, as the fairytales from our final sessions suggest, connection, confrontation with the unknown, acknowledgment of conflict, finding hope, and shared spirituality all had mutual influences within the groups in creating a positive transformative process, a shared “adventure”, where “questions” were heard even as “no final answer” was produced.

Limitations and Future Projects

There are limitations that we encountered with a review of this scope. We found important topics that could be pursued further using more specific analysis. During this project, we began to use multiple languages in the collaborative improvisation of the summary fairytale to better address situations in which participants did not all share a common primary language. A future project could investigate using such multilingual imaginative storytelling among international groups to facilitate and expand personal communication during times of crisis and rising tension among countries. Our groups also found that some improvisations developed a more global meaning that was beyond our immediate group. One of the central nonverbal metaphors that we did not review in this article is that had this potential to be viewed as a global metaphor involved dance/musical improvisation that expressed the grief that followed the surges of deaths in many countries. Another series of episodes addresses the nature of the dangerous spread of the virus as COVID-19 became more pronounced in Western countries. A future study could describe such metaphors more fully. Finally, our improvisations used multiple arts-based modalities. A future project could investigate how these expressive processes changed the initial verbal reports of events and responses of the daily lives to the crisis of the group members into a final fairytale about such experience through the creative transformations of multi arts-based improvisation. Such a study could help describe a process of change in Creative Arts Therapies. The positive outcomes of this group suggest that parts of the Creative Dialogues might be adapted and applied for support groups of people who have experience with long term COVID-19, or the death of someone with whom they were intimate during the health crisis. Applications of this approach could also be developed to help education and health/mental health professionals who are now struggling with emotional challenges such as burnout after their experiences during the pandemic.

About the Authors

Steve Harvey, PhD, BC-DMT, RPT/S, RDT is currently a consultant in the applications of Creative Arts Therapy. He and his wife Connor Kelly are leading an ongoing arts-based inquiry addressing the emotional communication of tragedy among different countries. Steve and Connor have recently moved back from Guam to their home in New Zealand.

Si Wang, MA, R-DMT, is currently managing a small studio in China that provides dance therapy experientials, workshops, and training to a Chinese audience. She participates in local and online creative activities that involves the body.

E. Connor Kelly, MA, BC-DMT, LPC, DTAA (Prof DMT) is currently a Professional Lecturer in the Dance/Movement Therapy program at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. She supervises and mentors DMTs and students in Australasia.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: saharvey1@yahoo.com; Tel.: +64272206856.

References

Bradbury, A., Warran, K., Mak, H. W., & Fancourt, D. (2021). The role of the arts during the COVID-19 pandemic. London: University College London. https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/download-file/UCL_Role_of_the_Arts_during_COVID_13012022_0.pdf.

Gover St. Gallery Staff. (2020). Taranaki artists in lockdown. New Plymouth, New Zealand: Gover St. Gallery.

Harvey, S. A., & Kelly, E. C. (2016). Arts based enquiry: Integrating narrative within movement. DTAA Journal, Moving On, 13(3/4), 2–9.

Harvey, S. A., & Kelly, E. C. (2018). Investigating the fairy-tale score used in physical storytelling. DTAA Journal, Moving On, 15(1 and 2), 2–12.

Harvey, S. A., & Wang, S. (2022) Creative arts online: An exploration of the quality of relationship when physical presence is not possible. DTAA Journal, Moving On, 18(1–2), 3–21.

Harvey, S., Jennings, C., & Kelly, E. C. (2020a). Creative dialogues across countries: Towards modern performance online during the global crisis related to COVID-19. Drama Therapy Review, 6(2), 121–126.

Harvey, S., Wang, S., Kelly, E. C., Wittig, J., Li, X., Peng, X., & Bordallo, A. (2020b). Creative dialogues across countries and culture during COVID-19. Creative Arts in Education and Therapy (CAET), 72–84.

Mochi, C., Harvey, S., & Cassina, I. (2022). Play and expressive arts to enhance professional development and personal growth in challenging contexts. In I. Cassina, C. Mochi, & K. Stagnitti (Eds.), Play therapy and expressive arts in a complex and dynamic world (pp. 138–158). London: Routledge.

Re, M. (2023, March 12). The resilient dancing of a mountain community. World Arts and Embodiment Forum: Dance Therapy Summit, Brighton, UK.