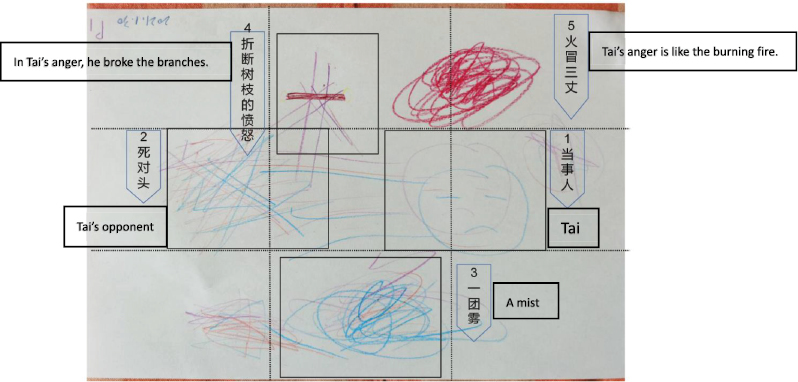

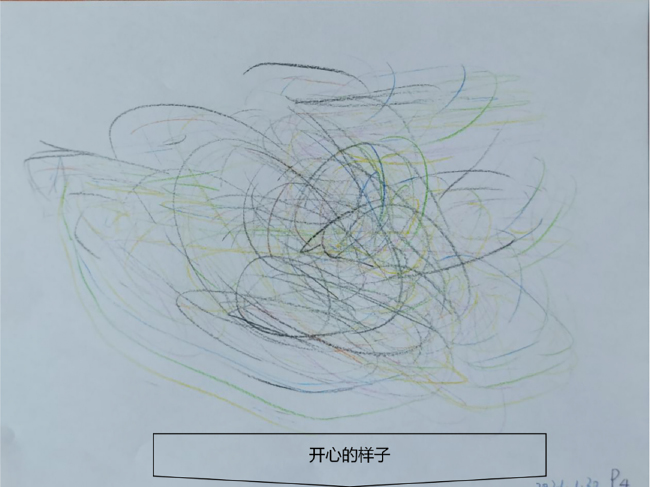

FIGURE 1 | Tai’s drawing of his anger.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2023) 9(2):164–179 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2023/9/12 |

Transforming Paper into a Therapeutic Drama Stage: A Case Study of a Chinese Primary Student on the Use of Drawing in a Drama Counseling Model

把画纸变为疗愈性戏剧舞台:运用绘画于戏剧咨询模式的中国小学生案例研究

Beijing Normal University, China

Abstract

This article presents a case study of how drawing paper can be integrated into a therapeutic drama stage. It will propose drawing in drama counseling as a new model of integral drama-based pedagogy. The article illustrates the connection of drawing, drama, and counseling. The model was developed by the author using the methods of integral drama-based pedagogy to counsel a Chinese primary school student who was angry about rejection and exclusion by his classmates. The study demonstrates how the student could use drawing paper to become his drama stage and how a student acted out a drama by drawing on that paper stage. The case study describes a method that could lead to a new therapeutic model in individual mental health counseling allowing for emotional catharsis, expression, and release. The article especially discusses the drawing in drama counseling model from Wu-wei of the Chinese culture.

Keywords: drawing in drama counseling, integral drama-based pedagogy, embodied emotion, emotional catharsis, drawing, Chinese culture, Wu-wei

摘要

本文介绍了一个关于如何将画纸融入疗愈性戏剧舞台的案例研究,指出绘画戏剧咨询是整合性教育戏剧的一种新模式,并阐述了绘画、戏剧和咨询之间的联系。该模型是作者在辅导一名受同伴拒斥而感到愤怒的中国小学生时,利用整合性教育戏剧的方法时发展出来的。本研究展示了该学生如何将画纸作为他的戏剧舞台、如何通过在这个纸质舞台用绘画来表演戏剧。案例研究描述了这种可以用于个体心理健康咨询的新疗愈模式方法,情绪在这个过程中得以宣泄、表达和释放。文章最后还特别从中国文化中之“无为”思想角度讨论了戏剧绘画辅导模式。

关键词: 戏剧绘画辅导, 整合性教育戏剧, 具身情绪, 情感宣泄, 绘画,中国文化, 无为

Introduction

Embodied Emotion

The embodied emotion theory holds that the perception, experience, expression, evaluation, and regulation of emotions are closely related to the body. Experiencing emotions, perceiving emotional stimuli, and reactivating emotional memories all awaken highly overlapping mental processes. Therefore, when the body re-perceives, experiences, expresses, evaluates, and regulates past emotions in a safe space, the emotions can be vented through this process leading to an emotional catharsis (see Niedenthal, 2007). This article offers a new process for the use of catharsis of embodied emotion by using paper to create a therapeutic drama stage.

Anger is a common emotion that could be used in attempting to resist uncomfortable feelings like shame, hurt, and loss (see Luxmoore, 2006). The experience and expression of anger in children has received little attention in children’s research compared with aggression and externalized behavior problems (see Kerr & Schneider, 2008). Although explicit anger may produce overtly aggressive behavior, implicit anger can be easily overlooked (see Sandstrom & Zakriski, 2004). As they age, children can suppress anger more effectively because they learn how to resist expressing emotions (see Zeman & Shipman, 1996).

Research shows that most children have difficulty expressing their experiences when they are psychologically injured by their families or peers (see Lev-Wiesel et al., 2016). This difficulty may be due to many reasons, such as fear of not being believed (see Miller & Cromer, 2015), concern about their families, and worry about social exclusion (see McElvaney et al., 2014). Researchers reported that the victims of bullying also tend not to disclose their experiences (see Mishna & Alaggia, 2005). If the bully is among their friends, they tend not to disclose for fear losing a relationship and doubt about the effectiveness of adult interventions. This prevents them from getting help and appropriate treatment, while exposing them to further violence (see Jenney et al., 2014). The research has also shown that anger is closely associated with low motivation and poor emotional regulation (see Smith & Furlong, 1998). The research should encourage teachers, parents, and counselors to pay close attention to repressed emotions.

Drawing and Drama Therapy

Research supports art therapy being an effective intervention in reducing the anger of aggressive children (see Liebmann, 2008; Alavinezhad et al., 2014). Drawing is a useful nonverbal tool for children to express hidden conflicts and feelings (see Lev-Wiesel & Liraz, 2007). Drawing can help children express themselves and convey feelings of unspeakable complexity. It can easily surface the relevant issues experienced by children and thereby accelerates the professional understanding of children’s experiences and provides opportunities for children to receive psychological support. Researchers have found that boys more than girls tend to portray violent and aggressive scenes in free drawings (see Feinburg, 1977; Reeves & Boyette, 1983). In the case study presented in this paper, I will discuss a boy’s drawing about his anger and propose a model to deal with it, which, in this instance, led to a catharsis and expression of embodied emotion.

Drama therapy uses drama and dramatic processes as media to facilitate change in the participants. Within drama therapy, the dramatic processes are therapeutic (see Duggan & Grainger, 1997; Emunah, 1999; Jennings et al., 1994; Landy, 1993). The drama process facilitates children’s nonverbal expression, control of their thoughts and feelings, and understanding of others. Drama therapy creates a space for children to play in imaginary worlds. While games take place in dramatic (“as if”) reality, actions, thoughts, and feelings can be real. Therefore, there is both distance and connection between play and everyday life (see Pendzik, 2006). Theater is not a mirror of life but its double, and herein lies its cathartic force. Theater can free the darkest aspects of human nature precisely because it expresses them for real, while negating them (see Artaud, 1958).

When drama therapy is used with children, it is more likely to be used with disorderly children and those with emotional problems (see Feniger-Schaal & Orkibi, 2020). Studies on the effect of drama therapy on the emotional abilities of children from high-risk families have shown that drama therapy stimulates and repairs emotional abilities. The therapeutic factors of drama therapy include the use of spontaneity, connection with life, play, transformation, and creative and witnessing process.

Drama therapy is usually used for children experiencing emotional and behavioral difficulties, and drama education is used for developing children’s growth. Bridging the gap between drama therapy and drama education has been explored by discussing the possibility for therapists teaching their clients and for drama teachers counseling their students through therapeutic drama (see Gaines et al., 2015; Holmwood, 2014, 2022; Ma & Subbiondo, 2022; Ma et al., 2023).

Integral Drama-based Pedagogy

Having worked in the field of mental health education and school counseling for 25 years, my research and practice have focused on education and counseling; I have been educating master’s students in school counseling and mental health education at Beijing Normal University, China. My teaching has gradually formed my views on education and school counseling. For children and adolescents in school, I particularly emphasize that the problems of students are mainly developmental. I have found a huge space between the concepts of education and therapy. Although there is counseling in schools, it is far from enough to effectively provide children with all the care needed. I believe that a new approach is needed to bridge the gap between counseling and education that can be summed up as “good counseling is educational, and good education is therapeutic.”

Accordingly, it is most important to consider how we bridge school counseling and education, expand their respective functions, and design the various therapeutic and educational methods applicable to the school environment. I believe that we need to make the function of education more natural and person-centered. In mental health education, pedagogy has long gone beyond the tradition of viewing education solely as teaching knowledge, and it is now also focused on the growth of personality and social development. To these ends in the past 25 years, I have been involved with the development of integrated drama-based pedagogy (IDBP), which combines the use of therapeutic and educational drama forms (see Holmwood, 2022; Ma & Subbiondo, 2022).

IDBP mainly uses drama, but it also integrates expressive arts forms such as music, drawing, dance, and movement. It can be classified as creative arts education as well as therapy. Its theoretical basis is in Wang Yangming’s mind thought and Sri Aurobindo’s integral education (see Ma & Subbiondo, 2022). Its practical basis is in contemporary human-centered psychological counseling and expressive arts therapy. The purpose of IDBP is to promote the integration of theory and practice to facilitate human development in education. IDBP pays attention to process and experience, and its principal characteristics are embodiment, learning, therapy, art, and culture. Usually, IDBP is carried out in groups, using large group dynamics to promote connection, cooperation, and creativity among group members as well as promoting the personal and social development of the participants. IDBP is a middle path between educational drama and drama therapy, and it is very applicable to mental health education.

Studies on IDBP mostly focus on administrators, teachers, and pre-service teachers, and they have found positive effects in promoting embodied emotional awareness and expression, interpersonal connection, self-integration, and micro-creativity (see Ma, 2023; Ma et al., 2023). Similarly, positive effects have been found in recent years in group counseling for children with special needs based on creative arts education (L. Ma, Research report on integrated education project for children with special needs in primary school based on creative arts in education and therapy, unpublished report, 2023). In using drawing in drama counseling, I am exploring the application of IDBP’s approach to individual student counseling.

The use of creative arts in counseling emphasizes the integrated use of art forms. Although drama therapy has a positive transformative effect on the personality and sociality of participants, it is usually implemented in a physical space. When the physical space is moved to the paper, the paper is used as a stage, and the child uses a pencil to manipulate the figures to carry out dramatic action. As a new and easily accessible form of IDBP, it can be applied to children individually to effectively promote healthier emotional responses. In this article, I will present new findings to support my new model of IDBP, integrating drawing and drama into counseling.

Using Drawing in the Drama Counseling Model

This paper introduces a practice-based case study in which I, serving as a counselor, integrate the elements of drawing, drama, and counseling by encouraging a primary school student to use the drawing of comic strips to create the drama. I have named this new practice model of IDBP “drawing in drama counseling.”

In this process, the student spontaneously uses drawing, projects himself as a role figure in the drawing, and unfolds the dramatic design and performance of scene after scene. I serve the role of audience and facilitator who builds a relationship with the student that is respected, trusted, understood, and accepted. In this relationship, the student can vividly present his emotions including that of suppressed anger in the process of drawing. In this instance, aggression is expressed, anger is cathartic, and emotions are purified and regulated. At the end of the “performance,” the student voluntarily retreats from the role of the virtual self and returns to the real self.

Case Study

Basic Information about the Case Study Where I Am Using the Pseudonym of Tai

Tai is a 7-year-old boy who is a second-grade student. His teachers and parents reported that he is unmotivated in school, inattentive in class, and withdrawn when encountering difficulties. Parents and teachers have told me that they do not know how to help him.

When I met with Tai, his parents brought his final examination paper in his Chinese language class, which had a low score. To indicate Tai’s difficulty concentrating in class, the teacher emphatically wrote on the paper two sentences in red: “Listen carefully in class. Keep up with the teacher’s rhythm.”

The Process of Drawing in Drama Counseling

After I saw the teacher’s two sentences, I talked with Tai regarding his understanding of their meaning. He shook his head and said, “I don’t know,” and he began to sit upright and then bowed his head. I sensed that he was getting depressed. When I invited him to talk about his class, his voice was protracted and low, and he said: “I…don’t know. I don’t…know.”

Find Descriptive Words to Express Feelings

While emotions are a state of mind, they are also physically reflected. For example, Tai’s whole body lost spirit, he became listless, and he did not want to open his eyes. He rubbed his eyes with both hands, and when he opened his eyes, he was looking upward. He shrugged his head, and he was almost crouched on the table. He said, “When I think of class, my feeling is ‘Shi da da’ (湿答答, Chinese pronunciation).” The feeling of “Shi da da” is losing soul and body energy and feeling weighted down. I use the Chinese word because there is no one-word equivalent in English, and it precisely described his state of physical and mental weakness and depression.

Discover an Externalized Vehicle for Expressing Feelings and Emotions

Tai’s mother praised him for being talented at discovering new features of the mobile phone, and he often used the emoji of the “invincible stickman” to express his emotions. I was very interested to have Tai show me the stickman emoji, and I listened carefully to him introducing the meaning of each variation of the emoji.

There are two types of stickmen: one is a red-haired stickman with a sword in his hand and an angry look on his face, and the other is blue-haired. Tai said that he is a blue-haired stickman who desperately wants to defeat the red-haired stickman, and he made a crunching sound in his mouth while pointing to the emoji. He stressed that blue stickmen are invincible. There was a stickman who was driving an armored car, and Tai made the “bang” sound of a cannon. He said that there is also a stickman who is very powerful and can penetrate the earth. These stickmen are very angry, and they want to knock each other down. After listening to Tai’s introduction, I felt that he was dealing with particularly severe anger that he had not been expressing, and these emojis were vivid symbols that allowed him to express that anger.

After introducing me to the various stickmen emoji and seeing that I had paid close attention and understood his use of them, Tai’s mood improved, and he regained energy. He said: “Ultraman, fly slowly, fly until half past five in the morning. At half past five, there was a bomb set off which blew up Ultraman.” I interpreted the invincible stickman and the blown-up Ultraman as projecting Tai’s anger. I asked Tai: “Who is Ultraman?” His favorite emoji showed that there is a lot of anger in him, and I asked him who was the target of his anger. Tai said, “My nemesis. A lot of people. I can’t count them all.” I invited him to tell me just one. He said Ding, a classmate. I asked, “What does Ding look like?” Tai said he could not say clearly, so I invited him to draw his nemesis on paper.

Set Roles

Tai said that Ding was fat, but his description was unclear. I Invited him to try drawing different shapes of Ding. He took two different colored pens simultaneously, one purple and one blue, and he represented a triangle in the center of the drawing to the left. He drew another circle to the right, and he drew the eyes with two horizontal lines and the downward curved mouth. The image was unhappy as it was emphatic and unpleasant. In the triangle and circle, two individuals who look so different, jump on the paper, showing the contradiction and tension between the protagonist, Tai, and antagonist, Ding (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 | Tai’s drawing of his anger.

Find the Desire and the Experience of the Protagonist

Tai said, “I’m not happy when I see Ding because he always wants to fight, fight, fight.” Tai drew the triangle with his pen. In the lower third of the center of the picture, he drew a blue tangled ball of thread and said that it was a fog. He indicated that he wanted his enemy to disappear. After drawing this blue fog, he let out a long breath. He said that he was relaxed because Ding had disappeared. The drawing reflected his very unhappy, angry, and confused emotional state.

When I invited Tai to talk about his dislike of Ding, he explained: “When I helped him pick up the paper airplane that fell on the ground, Ding scolded me and told me to go away, the farther the better. I ignored him, and I let him speak for himself. But I was very unhappy. Sometimes when I saw him, I almost broke my pencil in anger. He asked me to draw for him, and I used the pen hard, and I broke the tip with a crash. I don’t like to draw my nemesis.”

The representation of Tai is not tall and his body looks weak. Facing the big Ding, he was rejected and scolded by him, and although he did not return the favor, Tai was very angry. His parents said they had seen his pencil case with broken pencils. It was clear that Tai vented his inner anger at being bullied by Ding by breaking his pencils.

Tai said: “There’s another guy, my nemesis. Often before I started playing, he asked me to quit. I often break tree branches and get angry.” Tai then drew tree branches on the screen, and he said: “Just like that, holding the branch in my left and right hands, it breaks! When I think of them, I get angry.” He drew a red ball of thread in the upper right corner of the drawing and emphasized that “Fire is raging!” (Figure 1).

Tai ignored Ding and the other nemesis, but he never told them that he did not like their attitude toward him. They also did not know that Tai does not like their behavior. Tai did not tell his parents that he was being bullied by Ding and the other student at school.

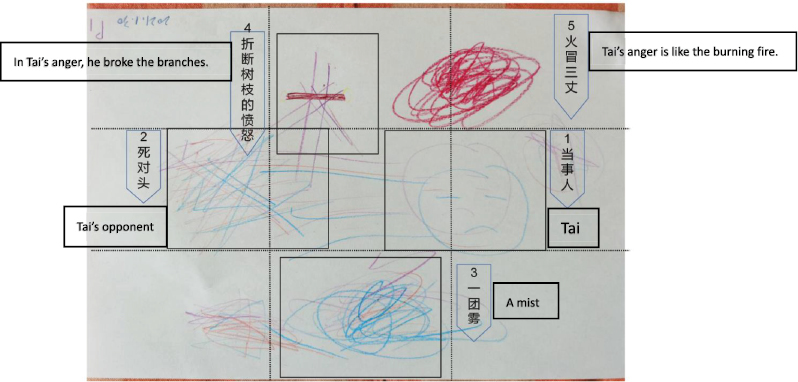

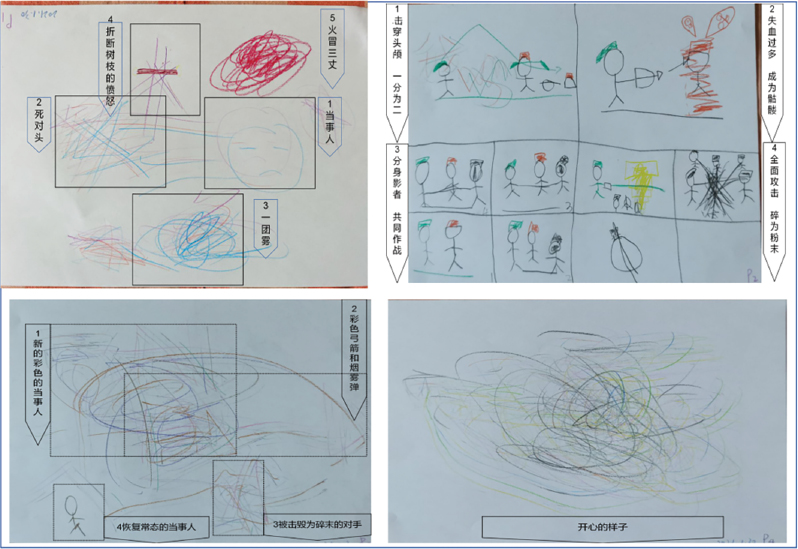

Use Symbols to Unfold the Drama Process and Further Vent Anger

Tai said that he wanted to draw a stickman, and he first drew horizontal and vertical dividers on a new white piece of paper, dividing it into four large spaces (Figure 2). Then Thai began his cross-play in the drama space of the paper. The first space is in the upper left corner of the paper. Tai is the protagonist of this drama. He set up a stand-in for himself by drawing a stickman in a green hat, and he capitalized the word “I,” which was Tai’s “double.” Double, a concept of the psychodrama technique, is a psychological alter ego of the protagonist. It is also the protagonist’s inner deep experiences and images, which are the protagonist’s own private domain (see Kipper, 2002; Toeman, 1946).

FIGURE 2 | Tai’s dramatic role-play process on the stage of paper.

Far away from him, he drew another stickman in a red hat. Between the two stickmen, Tai uses “vs.” to represent that they are in opposition. The stickman in the red hat is the antagonist, and he used a green polyline to indicate that he shot an arrow at his antagonist. The arrow pierced the antagonist’s head, splitting it in two. He drew two semicircles next to him, representing the antagonist’s head.

In the upper right corner of the paper, second space, Tai drew a stickman on the left saying, “This is me, with a bow and arrow.” He also carefully drew a line representing the ground. This detail indicated that he stood firmly on the ground, and it showed his confidence. He shot an arrow at his antagonist. Then, he drew the dotted line and made a “ticking” sound as the antagonist bled. He then used red lines to paint his antagonist from bottom to top, filling them with layers of broken lines. “It’s a lot of blood,” he said. Two speech bubbles are drawn on the antagonist’s head, and a skull is drawn in each bubble, indicating that he eliminated the antagonist.

In these two figures, Tai’s double delivered a deadly attack that eliminated the antagonist which made him very happy.

The lower left corner of the paper, the third space, Tai said, would have four small pictures. He divided the fourth space in the lower right corner into four small pictures. Here Tai developed his double’s shadow. Behind the antagonist, Tai drew a black man and said that it was a shadow avatar, a shadow of the Tai’s double. It was split from the double. Tai’s double takes a sword and joins shadow against the antagonist. The shadow stabs the antagonist and returns to the double. Tai used an arrow to represent this return. Tai’s double and the shadow who fight opponents together are in small spaces 3 and 4.

Tai pointed to the corner and said, “The green-haired villain is the most powerful. He also has the emoji of Mecha, electric heavy hammer, armored car, so versatile.” Then, in the fourth space, Tai divided it into four small spaces. He drew the yellow part in the first small space, representing that the red villain launched a very powerful force, spinning like a tornado. However, the little green man shoots a laser sword at it and then withdraws. The other party’s head and body were separated, and he used black to indicate it. Tai stressed again, “Green-haired stickman is the most powerful.” He said he designed the avatar according to Peter Pan’s story, because Peter Pan’s shadow can be separated and sewn together in emergency situations. Tai’s double needs the urgent help of his assistant to increase his attack power.

In the second small space, Tai drew the black-haired person, representing four twins of the double. They fired at the white-haired man in the middle, shattering him to pieces. Tai drew many black lines, and he made a “click” sound in his mouth to indicate a strong attack. The victim is beaten into foam, and at the bottom, black dots are drawn to represent the broken image. In the third small space, Tai drew a twin of a double and uses a hammer to punch through the earth.

After his drawing, I asked Tai to tell me how he felt from the beginning of the drawing until now, and Tai said, “Very happy! ‘Unhappy’ has long flown away!” When I invited him to talk about his anger for Ding, Tai said, “It’s long since floated!” I inquired whether what he drew had anything to do with Ding? Tai said, “No!”

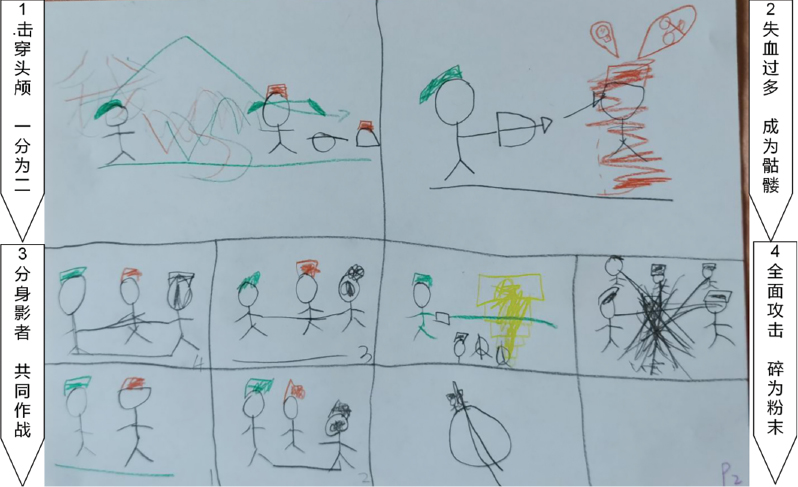

Tai proposed to draw a new picture. He took fresh paper and said that he wanted to draw colorful stickmen. He took four pens at the same time: pink, blue, black, and yellow. He said, “This is the new me,” an upgraded version of himself. He drew three lines on a white paper and said, “This is the latest version of me! It was a regular version before, but now it’s a new version, and I’m in color!” The double of Tai also carried a colored bow and arrow and was shooting an arrow. I asked Tai to identify his target. He said, “My antagonist. He’s still a very small one.” He drew a tiny stickman at the bottom, and with a kick and an arrow, the stickman trampled the small stickman into powder. Tai drew lines in various directions on the screen, indicating smoke bombs. Tai said, “bye-bye!” The picture is like a tornado—it represented all the battles have gone up in smoke.

Toward the end of the drawing, Tai drew a stickman in the lower left corner, representing himself. He said he has returned to his original appearance. He pointed to the picture saying, “Actually, it’s a Mecha.” I asked what a Mecha did, and he said, “Get bigger!” Mecha was Tai’s powerful mask, making him very powerful. Tai finished his role in the drama. Role-play was over (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3 | The new Tai de-roled, coming back to himself.

I clearly felt Tai’s mood was much better, and he was getting happier. He was very engaged in drawing, acting, narrating, and responding to my questions. Now that the emoji were no longer directly related to his opponents in school, Tai’s emotions were no longer directed at anyone. His anger has been vented.

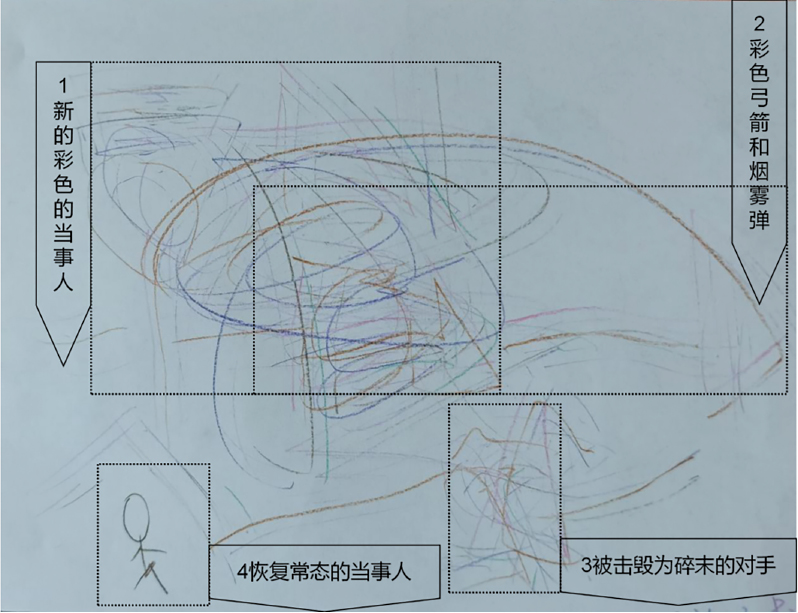

Assess Emotional State of Tai after using Drawing in Drama Counseling Process

Tai took a new piece of paper and four pencils: yellow, black, green, and blue. He drew circles that looked like a flying dragon and a dancing phoenix. Tai said he was very happy (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4 | Tai’s delightful feeling.

Summary Analysis and Discussion

Practice-based New Model of Drawing in Drama Counseling

For Tai, the process is not simply one of free drawing: it is the therapeutic use of drawing and different than classical art therapy. The model integrates some of the process of drama therapy; however, it is not classical drama therapy. The drama stage is the paper, and the process integrates drawing, therapeutic drama, and counseling. This process is a new integral model, which I named “drawing in drama counseling.” It applies integral drama-based pedagogy to individual counseling.

Drawing in drama counseling in this case is a complete process of action, in line with Aristotle’s classic view in his Poetics (see Vives, 2011). This case has a beginning, a middle, and an end in 50-minute frames. At first, Tai simply externalized his feelings by drawing lines and clusters of lines to express his inner unhappiness and anger. Starting from this initial level of emotional engagement and expression, subsequent drawing used emoji to unfold a dynamic dramatic process in the virtual drama stage on the paper. This process clearly presents role-taking, doubling, confronting, finishing, and de-roling.

Catharsis Effect of the Drawing in Drama Counseling

In this model, the paper is an empty stage, divided by lines, and the setting of the drama. The protagonist plays the emoji role, designing props, actions, lines, and plots. He presents martial arts action with comic strip-style drawing making the drama unfold, shaping himself into a powerful and victorious warrior.

In Chinese, the right side (戈) of the word drama (戲) presents the image of a weapon, as it was etymologically related to war (see Shi, 2019). For the Chinese, the origin of drama is one stage with two people fighting passionately. The embodied emotions of anger in this case are vividly presented with battles filled with conflict and aggression. Tai resorted to them to role-play on paper. He chose to play himself as a stickman, and the stickman transformed himself into a variety of weapons, avatars, and Mecha to increase and expand physical strength and power. He also confronted opponents in various situations and defeated them in a major victory.

Weak, bullied, and powerless in life, he became a powerful and strong warrior with infinite power in the play. The externalized angry emotions swept into the virtual space on paper with strong and destructive energy. It vented out with the power of the character, and it led to an emotional catharsis. The cathartic process has a strictly moral dynamic: it purifies or heals bad passions by showing disastrous results. Humanists, as well as most classical theorists, have made such a classic interpretation of Aristotle’s statement about catharsis (see Vives, 2011).

Autonomy, Spontaneity, and Creativity in Drawing in Drama Counseling

IDBP draws on human spontaneity, autonomy, and creativity. Tai showed these qualities throughout the process: his choice of colored pencils, spatial use of paper, choice of the double, and design and control of the dramatic process in drawing. Projective role-play helped him vent pent-up anger and purify his emotions. In dramatic projection, the different dimensions and experiences of the self were projected in the content and performance of the drama. Dramatic projection establishes the relationship between the psychological state of the individual and external dramatic form. It shows the relationship in the process of dramatic action (see Jones, 1996). All the drawings and scenes on Tai’s paper contained his unintegrated thoughts and feelings. The paper became what Winnicott (1971) considered the transitional space of illusion and reality.

In the end, Tai independently added the roles of colorful drawing and a new version of self, strongly and energetically representing the birth of his new self. He took the initiative to de-role and return to his actual self. Autonomous de-roling is to mentally withdraw the phantom characters projected in the drama space and to psychologically widen the distance between fantasy and reality.

Violence Can be Depicted in Drawing and Role-play in Drawing in Drama Counseling

Studies have shown that dramatic scenes may not significantly correlate with the life experiences of the participants. More research is needed to better assess the relationship between artistic expression and psychological problems. Children are not painting real experiences, but imaginary experiences: there appears to be no direct correlation between the representation of violence in painting and the occurrence of violent behavior in real life (see Malchiodi, 2001).

The space of the therapeutic drama is related to that of real life, but it may not completely reflect daily life. Actors perform as they wish without any serious consequences (see Sontag, 1977). Therapeutic drama must be completely removed from reality to satisfy unconscious desires without causing anxiety and disaster (see Solomon, 1950). Tai understood that he was role-playing a drama game and that playing Mecha substituted for making himself strong enough to fight outside bullying. He experienced the joy of success in defeating his opponent, a sense of competence that compensated for his frustration of being bullied by powerful and assertive peers in real school life. Studies reported the empowering benefits of the desire for revenge fantasies (see Lev-Wiesel et al., 2023), such as feeling satisfaction (see Crombag et al., 2003), reducing aggression (see Gollwitzer & Denzler, 2009), enhancing victims’ feelings of empowerment (see Strelan et al., 2020; Twardawski et al., 2021) and sense of justice (see Funk et al., 2014).

The “Wu-wei” in the Drawing in Drama Counseling Model

“Wu-wei,” i.e., effortless action, is the Chinese spiritual ideal, and it is drawn from the “Tao Te Ching,” the classic work of Taoist thought used in psychotherapy (see Rogers, 1961; Slingerland, 2000; Craig, 2007). Artistic expression is a process of nature (see McNiff, 2015). Wu-wei sheds light on the central phase of arts counseling, and it is an essential attitude for counselors. The process can only be beneficial if the client and counselor both let go of knowing and willing to “let it be.” This notion is like Heidegger’s concept of Seinlassen (letting something show itself as it is in itself), and to Shaun McNiff’s injunction to “trust the process” (see Levine, 2015; McNiff, 2016; Levine & Levine, 2017). In artistic creation, the artist is engaged in effortless action of Wu-wei (see Sommers-Flanagan, 2007; McNiff, 2015).

I did not judge and intervene in the aggressiveness shown by the Tai, nor did I guide him as to how to unfold the drawing and the dramatic action. In the game space, I acted as a witness, an audience with feedback on the process of watching the drama. My questions prompted responses that increased Tai’s self-confidence. He designed and controlled the process of the drama, and I maintained a neutral, accepting, and holding attitude. Tai could safely interpret himself, remove all social and moral masks, and change into a well-armed Mecha to fight and win (Figure 5). This process maintained his self-integrity, and the emotional purification process was very conducive to his continued self-integrity and mental health.

FIGURE 5 | Tai’s whole dramatic role-play process drawing pictures.

Conclusion

This article used a practice-based case study to reveal that drawing in drama counseling complements the application of integral drama-based pedagogy in individual counseling in mental health education. This case documents that effective counseling is educational, and effective education is therapeutic. In practice, the new model of drawing in drama counseling could inspire teachers and counselors to work with children individually. I hope that my paper will inspire others to undertake more empirical case studies to support the efficacy of the drawing in drama counseling and to continually improve it.

About the Authors

Liwen Ma received her Ph.D. in Developmental and Educational Psychology from Beijing Normal University, China in 2005. She is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Education at Beijing Normal University. She is a member of the Institute of Educational Psychology and School Counseling, and the Founder and Director of Applied Drama and Expressive Arts Education Research Center. She is the Co-Editor of the Journal Creative Arts in Education and Therapy: Eastern and Western Perspectives. She serves as Associate Editor of the Journal Beijing International Review of Education. Prof. Ma is a member of the International Editorial Board for the Journal of Drama and Theatre Education in Asia (DaTEAsia).

Prof. Ma has created Integral Drama Based Pedagogy which has been internationally received by scholars, teachers, and administrators as a promising new direction for integrating educational and therapeutic counselling.

Her research areas are: Applied Drama, Expressive Arts in Education and Therapy, Mental HealthEducation, School Counselling, and Action Research. She is also an expert member of Art Therapy Group, Psychological Counseling and Clinical Committee of Chinese Psychology Society (CPS), and member of the International Drama and Education Association. She is a Member of the Board of International Association of Creative Arts in Education and Therapy.

Prof. Ma devotes herself to promoting people’s mental health through drama and other expressive arts, and focuses on practice and study of self-awareness, critical reflection, and active development of individuals and organizations in the arts process. She has extensively conducted workshops for primary and secondary school teachers throughout China.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: liwenma@bnu.edu.cn

References

Alavinezhad, R., Mousavi, M., & Sohrabi, N. (2014). Effects of art therapy on anger and self-esteem in aggressive children. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 113, 111–117.

Artaud, A. (1958). The theater and its double. New York: Grove Press.

Craig, E. (2007). Tao psychotherapy: Introducing a new approach to humanistic practice. Humanistic Psychologist, 35(2), 109–133.

Crombag, H., Rassin, E., & Horselenberg, R. (2003). On vengeance. Psychology, Crime and Law, 9(4), 333–344.

Duggan, M., & Grainger, R. (1997). Imagination. Identification and catharsis in theatre and therapy. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Emunah, R. (1999). Drama therapy in action. In D. J. Wiener (Ed.), Beyond talk therapy: Using movement and expressive techniques in clinical practice (pp. 99–123). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Feinburg, S. G. (1977). Conceptual content and spatial characteristics in boys’ and girls’ drawings of fighting and helping. Studies in Art Education, 18(2), 63–72.

Feniger-Schaal, R., & Orkibi, H. (2020). Integrative systematic review of drama therapy intervention research. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 14(1), 68–80.

Funk, F., McGeer, V., & Gollwitzer, M. (2014). Get the message: Punishment is satisfying if the transgressor responds to its communicative intent. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40, 986–997.

Gaines, A. M., Butler, J. D., & Holmwood, C. (2015). Between drama education and drama therapy: International approaches to successful navigation. p-e-r-f-o-r-m-a-n-c-e, 2(1–2).

Gollwitzer, M., & Denzler, M. (2009). What makes revenge sweet: Seeing the offender suffer or delivering a message. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 840–844.

Holmwood, C. (2014). Drama education and dramatherapy: Exploring the space between disciplines. London: Taylor & Francis.

Holmwood, C. (2022). A review of drama education (UK) and integral drama based pedagogy (China), western and eastern perspectives and influences. Beijing International Review of Education, 3(4), 517–531.

Jenney, A., Mishna, F., Alaggia, R., & Scott, K. (2014). Doing the right thing? (Re) Considering risk assessment and safety planning in child protection work with domestic violence cases. Children and Youth Services Review, 47, 92–101.

Jennings, S., Cattanach, A., Mitchell, S., Chesner, A., & Meldrum, B. (1994). The handbook of dramatherapy. London: Routledge.

Jones, P. (1996). Drama as therapy: Theatre as living. London: Psychology Press.

Kerr M. A., & Schneider B. H. (2008). Anger expression in children and adolescents: A review of the empirical literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 559–577.

Kipper, D. A. (2002). The cognitive double: Integrating cognitive and action techniques. Journal of Group Psychotherapy, Psychodrama & Sociometry, 55(2), 93–106.

Landy R. (1993). Persona and performance: The meaning of role in drama, therapy, and everyday life. New York: Guilford Press.

Levine, S. K. (2015). The Tao of poises: Expressive arts therapy and Taoist philosophy. Creative Arts in Education and Therapy, 1(1):15–25.

Levine, S. K., & Levine, E. G. (Eds.) (2017). New developments in expressive arts therapy: The play of poiesis. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Lev-Wiesel, R., & Liraz, R. (2007). Drawings vs. narratives: Drawing as a tool to encourage verbalization in children whose fathers are drug abusers. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 12(1), 65–75.

Lev-Wiesel, R., Eisikovits, Z., First, M., Gottfried, R., & Mehlhausen, D. (2016). Prevalence of child maltreatment in Israel: A national epidemiological study. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 11(2), 141–150.

Lev-Wiesel, R., Leibovich, I., Doron, H., Maman, T., Cohen, B., Moskowitz, N., Saady, I., Klein, L., & Binson, B. (2023). The reflection of desire for revenge and revenge fantasies in drawings and narratives of sexually abused children. Child & Family Social Work, 28(3), 681–689.

Liebmann, M. (2008). Art therapy and anger. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Luxmoore, N. (2006). Working with anger and young people. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Ma, L. (2023). Promoting the mental health of educators: workshops for China’s principals and teachers. Voices for Education Equity, 3, 61–73.

Ma, L., & Subbiondo, J. L. (2022). Integral drama based pedagogy as a practice of integral education: Facilitating the journey of personal transformation. Beijing International Review of Education, 3(4), 499–515.

Ma, L., Chen, Z., & Shen, X. (2023). An analysis of the structure of integral drama-based pedagogy: An approach to the social and emotional learning of teachers. Voices for Educational Equity, 1, 20–33.

Malchiodi, C. A. (2001). Using drawing as intervention with children who have experienced trauma or loss. Trauma and Loss: Research and Interventions, 1(1), 21–28.

McElvaney, R., Greene, S., & Hogan, D. (2014). To tell or not to tell? Factors influencing young people’s informal disclosures of child sexual abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(5), 928–947.

McNiff, S. (2015). A China focus on the arts and human understanding. Creative Arts in Education and Therapy, 1(1), 6–14.

McNiff, S. (2016). Ch’i and artistic expression: An East Asian worldview that fits the creative process everywhere. Creative Arts in Education and Therapy, 2(2):12–20.

Miller, K. E., & Cromer, L. D. (2015). Beyond gender: Proximity to interpersonal trauma in examining differences in believing child abuse disclosures. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 16(2), 211–223.

Mishna, F., & Alaggia, R. (2005). Weighing the risks: A child’s decision to disclose peer victimization. Children & Schools, 27(4), 217–226.

Niedenthal, P. M. (2007). Embodying emotion. Science, 316, 1002–1005.

Pendzik S. (2006). On dramatic reality and its therapeutic function in drama therapy. Arts in Psychotherapy, 33, 271–280.

Reeves, J. B., & Boyette, N. (1983). What does children’s artwork tell us about gender? Qualitative Sociology, 6(4), 322–333.

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Sandstrom, M. J., & Zakriski, A. L. (2004). Understanding the experience of peer rejection. In J. B. Kupersmidt & K. A. Dodge (Eds.), Children’s peer relations: From development to intervention (pp. 101–118). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Shi, Y. (2019). [An overview of the meaning of the word ‘drama’’]. https://www.bilibili.com/read/cv11837378/ (accessed 22, 6, 2021).

Slingerland, E. (2000). Effortless action: The Chinese spiritual ideal of Wu-wei. Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 68(2), 293–327.

Smith, D. C., & Furlong, M. J. (Eds.) (1998). Introduction to the special issue: Addressing youth anger and aggression in school settings [Editorial]. Psychology in the Schools, 35(3), 201–203.

Solomon, A. P. (1950). Drama therapy. Occupational therapy: Principles and practice. JAMA, 143(17), 1529.

Sommers-Flanagan, J. (2007). The development and evolution of person-centered expressive art therapy: A conversation with Natalie Rogers. Journal of Counseling and Development, 85(1),120125.

Sontag, S. (1977). The image-world. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Strelan, P., Van Prooijen, J. W., & Gollwitzer, M. (2020). When transgressors intend to cause harm: The empowering effects of revenge and forgiveness on victim well-being. British Journal of Psychology, 59(2), 447–469.

Toeman, Z. (1946). Clinical psychodrama: Auxiliary ego double and mirror techniques. Sociometry, 9(2/3), 178-183.

Twardawski, M., Gollwitzer, M., Altenmmuller, M. S., Kunze, A. E., & Wittekind, C. E. (2021). Imagery rescripting helps victims cope with experienced injustice. Zeitschrift Fur Psychologie, 229(3), 178–184.

Vives, J. M. (2011). Catharsis: Psychoanalysis and the theatre. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 92(4), 1009–1027.

Winnicott, D. (1971). Playing and reality. London: Tavistock.

Zeman, J., & Shipman, K. L. (1996). Children’s expression of negative affect: Reasons and methods. Developmental Psychology, 32, 842–849.