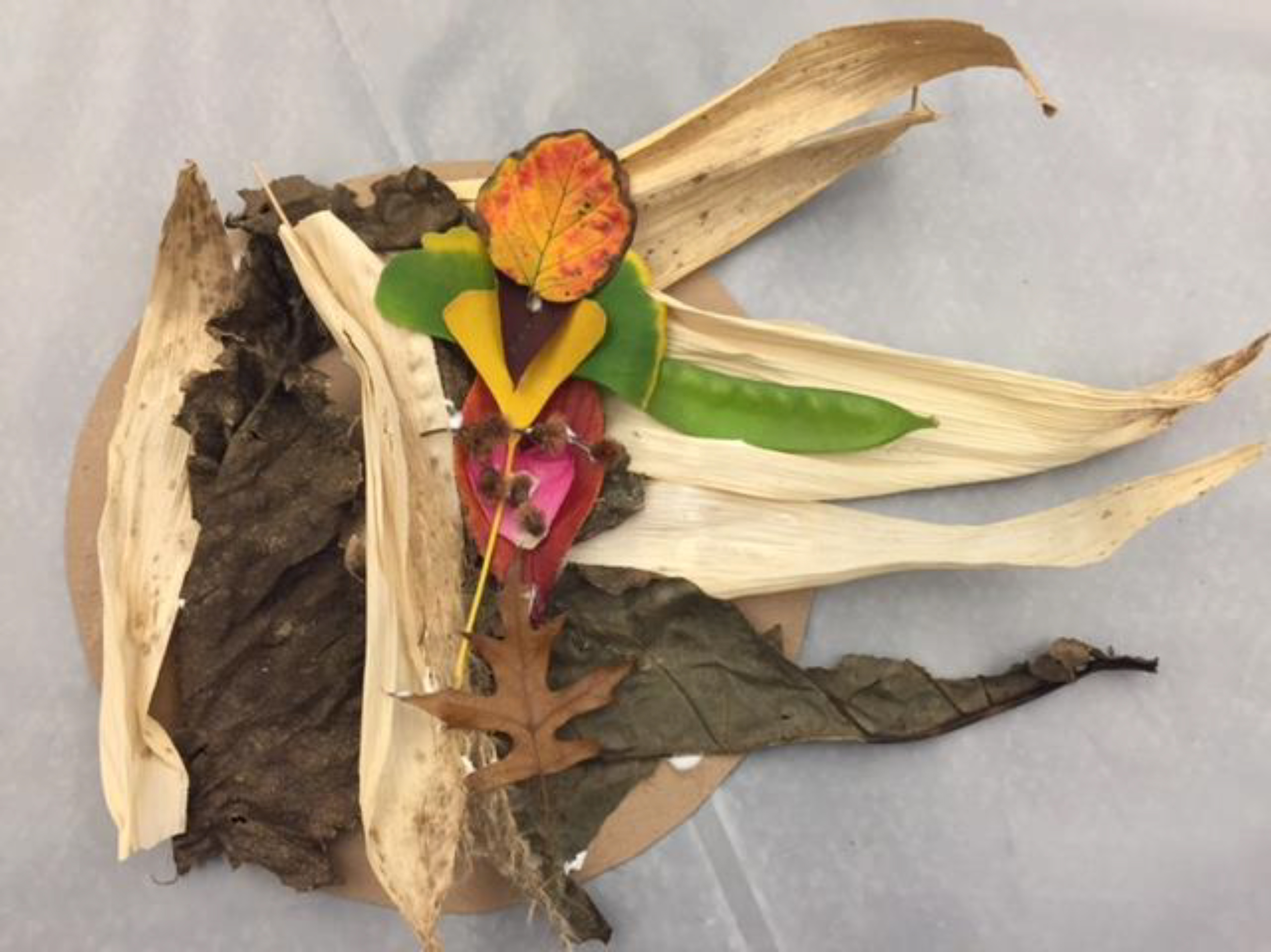

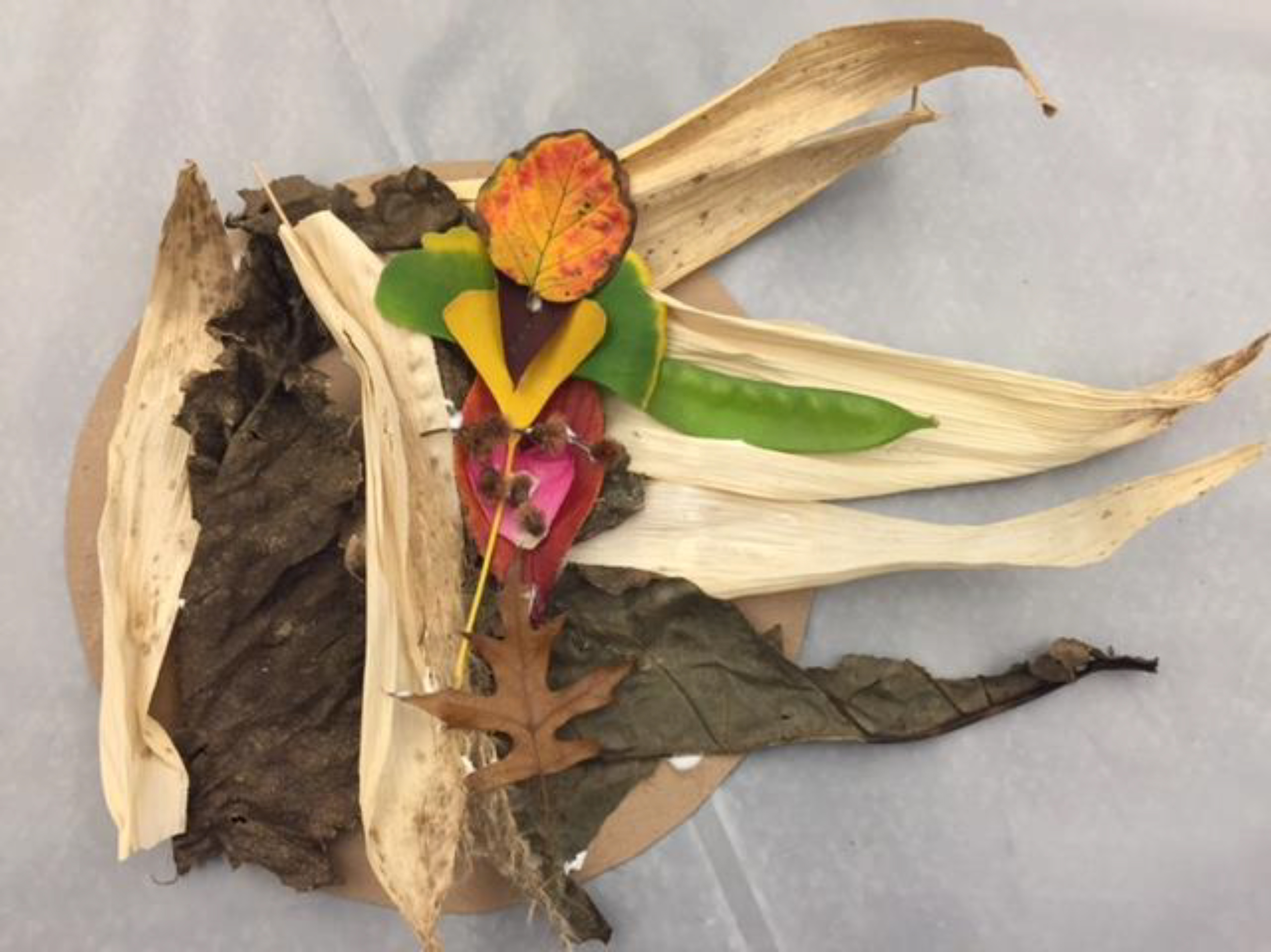

FIGURE 1 | The mandala made by 72-year old woman and explained as a symbol of her experience related to aging.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2018) 4(1):3–9 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2017/3/2 |

The ‘Green’ Mandala: Where Eastern Wisdom meets Ecopsychology

“绿色”曼陀罗:东方智慧遇到生态心理学

St.-Petersburg Academy of Post-Graduate Pedagogical Training, Russia

Abstract

Mandalas are circular images often created in various religious and indigenous traditions. Due to the development of Jungian analysis and transpersonal studies diagnostic and therapeutic potential of the mandala was extensively explored. Analytical psychologists and art therapists understand visualized or created mandalas of their clients as the symbolic mirror of the psyche, a means of containing and integrating its energies, both conscious and unconscious dynamics and states of mind.

This paper presents ecological and environmental perspectives on our understanding and therapeutic application of the mandala as an expressive/creative tool that helps to bring the arts and nature together and provide beneficial effects both for human and nonhuman worlds. Basic theoretical, ethical and instrumental ingredients related to the ‘green’ mandala, or eco-mandala, together with case vignettes illustrating their therapeutic application and functions will be presented.

Keywords: mandala, environmental, ecopsychology, ecotherapy, art therapy.

摘要

曼陀罗是通常在各种宗教和土著传统中创建的圆形图像。由于荣格分析和超个人研究的发展,对曼陀罗的诊断和治疗潜力进行了广泛的探索。分析心理学家和艺术治疗师将他们客户的可视化或创造的曼陀罗理解为心灵的象征性反映,这是一种遏制和整合其能量的手段,既有意识的也有无意识的动态和精神状态。

本文将我们对曼陀罗的理解和治疗应用的生态和环境视角作为一种表现力/创造性工具,帮助将艺术和自然融合在一起,并为人类和非人类世界提供有益的影响。本文还将介绍与“绿色”曼陀罗或生态曼陀罗相关的基本理论、道德和机制成分,以及说明其治疗应用和功能的案例简介。

关键词: 曼陀罗, 环境, 生态心理学, 生态疗法, 艺术疗法

Introduction

The term ‘green mandala’ is introduced here to define either pre-existing natural circular forms or those created by humans (co-creating together with nature) along with the use of natural materials and environments. The mandala will be presented as an eco-psychological concept and a form of eco-art therapy practice which helps to achieve both individual health and well-being and also meets public and environmental health outcomes. The perennial nature of the mandala as one of the core symbols of the spiritual traditions of East and West will be considered within the context of the modern psychological idea of the personality – along with its relationships to wider social and environmental networks. This will enable a deeper understanding of the creation of the mandala as an environmental action – rooting it not so much in the need of creative self-expression (in the traditional Western sense of the word) but within a strong motivation to support and serve both nature and life.

The human inclination to interact with and create mandalas will be explored through the perception of natural environments and living forms both as a kind of a supportive field and as a living entity. These environments and forms can be highly attractive to humans – not only due to their practical value but also because of their aesthetic, cognitive, and spiritual meanings and their ability to support inner harmony and nature within human beings.

As any other method or instrument applied in ecopsychology and ecotherapy (and eco-art therapy as one of its forms), making mandalas out of natural materials and/or within natural environments is based on the premise that the health of the planet impacts our health and acknowledges that a certain synergy between the well-being of communities, individuals and the environment (in which they live) does exist. The central goal of creating and using the mandala from both an eco-psychological and eco-therapeutic perspective is to achieve well-being as an inner state of wellness; such wellness includes physical, mental and emotional states of consonance which exist in a healthy environment.

The mandala in cultural traditions and as a psychological concept and therapeutic instrument

A mandala is a spiritual and ritual symbol in Hinduism and Buddhism, representing the universe. In common use, ‘mandala’ has become a generic term for any diagram, chart or geometric pattern that represents the cosmos metaphysically or symbolically; a microcosm of the universe. It can be acknowledged that the circle as a natural form and a human creation symbolizes many things for different people and provides healing in cultural traditions worldwide.

Contemporary interest in the mandala was initiated by Jung who prompted research relating this phenomenon within Western psychotherapy. Jung adopted the Sanskrit word ‘mandala’ to describe the circular drawings he and his patients did. Jung observed the mandala in his own as well as his patients’ dreams and drawings which had been composed during certain states of mind. The discovery of the mandala led Jung to abandon the idea of the superordinate position of the Ego and inspired him, instead, to formulate the theory of the Self and the individuation process (Jung, 1973, 1976).

The appearance of the mandala in patients’ dreams and artworks is usually interpreted as a representation of human wholeness or as a reflection of a psychological centripetal process through which the personality achieves or restores inner balance and harmony. Since Jung, the mandala has been used as a therapeutic instrument in a number of different ways. It is often applied in psychodynamic, insight-oriented therapy – giving a client the means by which to externalize the inner processes and states of their mind and to integrate certain idiosyncratic experiences and qualities too. The making of the mandala itself becomes a projective instrument of centering and balancing personality as well as a meditative and relaxing procedure that reflects or anticipates states of Ego-Self integration and the individuation process. Mandala making can be also used outside insight-oriented psychotherapy as a form of healing or self-help practice that helps to reduce or prevent stress-related symptoms and achieve psychological integration.

The interpretation of the mandala in psychology is, however, different and is dependent on the particular theory of the personality implied. As Hillman (1995) states, “There is only one issue for all psychology. Where is the “me”? Where does the “me” begin? Where does the “me” stop? Where does the “other” begin? ...For most of its history, psychology took for granted an intentional subject: the biographical “me” that was the agent and the sufferer of all “doings”. For most of its history, psychology located this “me” within human persons defined by their physical skin and their immediate behavior. The subject was simply “me in my body and in my relations with other subjects”. (p. xvii)

Over the past few years, these ideas of the personality have been revisited with a view to gaining a new perspective on the idea of personality and its relationships with the world surrounding it. Hillman believed that “Adaptation of the deep self to the collective unconscious and to the id is simply adaptation to the natural world, organic and inorganic. Moreover, an individual’s harmony with his or her “own deep self” requires not merely a journey to the interior, but a harmonizing within the environmental world”. (Hillman, 1995, p. xix).

The mandala as a representation of the human connection with the natural environment

Visualizing and making mandalas cannot be perceived only as an inwardly-oriented process but can also be seen as a means of relating to the environment. Such procedures can involve an attunement to various environmental phenomena by which not only the inner processes of the body and the psyche can be externalized and brought to the conscious mind, but qualities and resources implied within the environment can also be internalized – so both inner and outer worlds can come together.

This core function of the mandala can be explored through an acquaintance with the processes of human environmental creation from prehistoric times – for with the development of such disciplines as environmental psychology and ecopsychology, a new perspective on and understanding of the mandala as a tool both for therapy and for the harmonizing of human relationships alongside the natural environment has been created. Holistic therapies, various ‘green movements’ and post-modern environmental and ecological arts now help to expand our understanding of the mandala as an expression of the human need to re-establish healthy bonds with the environment.

Furthermore, the human inclination to create and use man-made circular forms in healing and spiritual practices (including those related to the natural environment) can be considered as an expression of the human instinct of mutually supportive relationships with nature and a healthy resonance with many circular forms abundant in the natural world. This inclination can be explained from the perspective of the biophilia hypothesis (Wilson, 1984, 1993), which postulates the existence of a pervasive attraction that draws people to nature with its different mineral, plant and organic forms and often implies circular structures as representative of a healthy and contained life.

This biophilia hypothesis is also based on the presumption that our relationship with these natural forms can be mutually supportive – going beyond their practical value as food or medicine and often enabling us to perceive them as emotionally compelling symbols.

Creating the green mandala can be acknowledged as a viable expression of the art of biophilia. (Kopytin, 2016) defined this as a form of creative activity within natural environments (green spaces). The act of creating the mandala from natural materials appears to share similar qualities with (and to be based upon) the values and principles of the Japanese art of Ikebana. This revered practice is a blend of aesthetic and spiritual expression and seeks composure, balance, and clarity within a structured reflection of the fully formed self.

Environmental psychology helps to expand our understanding of the mandala as a dynamic representation of the positively constructive interplay between individuals and their surroundings. This perception of our constructive human interaction with the environment can be enriched through the use of concepts such as the personalization of space/environment (Gregory, Fried, and Slowik 2013; Heimets 1994) as it relates to psychosocial aspects expressed through territoriality and, additionally, people’s need to maintain a sense of belonging, ownership and control over their space.

Personalization can also be defined as human behavior focused on bringing the distinctive features of an individual to bear on the environment. Personalization provides people with a greater sense of ownership and control over a space and helps to establish and maintain a sense of individuality (identity). As a result of the personalization and appropriation of a space, existing ego-structures can be brought forward to and expressed within the environment, and a further development and reconstruction of the personality and appropriation of new, positive characteristics of identity becomes possible. The act, therefore, of creating the green mandala can be expressed as an ecological form of personalization based on sustainable and supportive human interactions with the natural world.

Creating the mandala as an expression both of the art of biophilia and as an ecological form of personalization can be related to the ecologically grounded personality theory which requires the development of personality be recognized as taking place within a wider matrix of existence – including those with natural environments. This awareness of various acts of personalization and appropriation of the natural environment and an additional acknowledgement of the subsequent effects on human beings has paved the way for a developmental personality theory with the main focus on the formation of an Eco-Identity, “... a kind of self-perception and self-understanding that is linked to one’s sustaining relationship with nature and her/his involvement in some positive activity in or with nature.” (Kopytin, 2016, p.21).

Eco-Identity can be established (and subsequently developed) when a person becomes involved in some activity involving nature – including the expressive/creative acts. The arts can be regarded as one type of environmental action with a strong self-regulating function – together with many other activities which are typical examples of eco-therapy: gardening, animal encounters, spending more time in ecologically healthy settings or, additionally, actively working on maintaining and restoring eco-health.

Materials and environments implied in creating the green mandala

Materials

Creating the mandala as a form of environmental and ecological expressive therapeutic practice can take place either indoors or outdoors, but must use mostly natural materials and forms. An increase in the varieties, structures, and types of materials (including such botanical ephemera as vines, leaves, fruits, flowering branches, flowers and seed pods as well as different kinds of soils, sand, stones, etc.) yields a richer, more complex sensual and symbolic field for the client’s exploration. Various art and junk materials, both found and man-made items and clients’ personal belongings can be used too.

The significance of natural materials and botanical ephemera, however, must be given particular emphasis because of their ability to evoke biophilic reactions. Botanicals also “acquire metaphorical vitality that individuals may experience at different conscious and unconscious levels of experience. Within [such an] interwoven relationship, it is unsurprising that botanicals become signifiers of specific human events as a part of the common language...simply touching, smelling and arranging botanical ephemera into pleasing symmetries can bring pleasure, alertness, and a sense of accomplishment.” (Montgomery, &Courtney, 2015, p.19)

Diehl (2009) believes that “The multitudes of fragrances, color, textures, tastes and sounds of plants awaken our senses.” She further explains that “sensory stimulation helps us connect with nature by engaging us physically, cognitively, and emotionally” (P.169). Such natural circular or spherical forms as flowers and fruits are abundant in nature and are often perceived as significant symbols of wholeness, harmony and protection; these support our link to the environment and enhance our ability to create similar forms.

Environment

The practice of creating mandalas as other types of activities typical for nature based or ecological therapies can take place in the wide environmental continuum. Some of these outdoor forms can be characterized by greater biodiversity, while working indoors requires an appropriate supply of natural materials. If time, weather and seasonal conditions permit, most (or at least some part) of the session can take place outdoors. Outdoor spaces used for such activities can vary considerably.

Urban spaces devoid of all forms of nature can be difficult to find. Some environments with a great diversity of plant forms can be discovered even in the midst of the city. Such spaces usually include at least some natural forms and some botanical ephemera with which participants can interact. Most towns and cities usually include such ‘green’ spaces as parks or gardens, etc. Today, national and international policies support the inclusion of the natural environment in the promotion of holistic health.

Creative activities involving mandala making can be arranged in such specifically accessible green areas as part of a hospital, a rehabilitation center, a shelter or a residential home etc. These activities may also be aligned to a private practitioner’s office as well as to municipal areas (parks, gardens, the beach etc.) or the ‘wild’ environment. As far as working outdoors is concerned, specific variations and a differing quality of environmental perception should be taken into consideration. The perception of an environment and subsequent modes of engaging with it can, however, depend not only on its quality but on the participants’ intentions and attitudes.

Therapeutic and restorative activities based on creating ‘green mandalas’

Creating mandalas as a form of ecotherapeutic/eco arts therapeutic practice is not only expressed within the original theoretical positions presented (above), but is also explored through practical implementation. The process of creating the green mandala occurs in three phases and is similar to Scull’s (2009) nature-connecting – including preparation, experience and debriefing of the experience.

The first phase introduces clients to the theme of creating the green mandala as a special form of eco arts therapeutic activity and also to the materials needed for such a session. Some indoor (or outdoor) warm-up activity helps to awaken the participants’ sensory awareness through touch, taste, smell etc. of surrounding natural spaces, objects and materials and provides a change in the participants’ perception of their environment. Establishing a focus on the topic to be explored and choosing a question or situation that will be most relevant for the day is usually included in this part of the session too.

The second phase is the actual working session where clients create the mandala and interact with it (or through it) with themselves and with the environment. They can install their mandala in the landscape or use such action-based creative activities as performance, dance and movement, personal or group rituals or multimedia events. More concentrated forms of reflective and creative activity such as journaling or creating narratives can also be implemented in this session. In the third phase, clients step back from their creations and observe and discuss their work they have completed – allowing both insight and perspective.

Assignments related to creating mandalas can be open-ended or based on certain themes. Open-ended assignments encourage participants to walk outdoors in the environment or to explore natural materials indoors and pay attention to scenery or objects they find most interesting or appealing for them; they can task them to select materials, or simply take photographs or draw scenery or objects. Sessions can be more focused on particular topics or themes as “The mandala as a response to my question/aspiration,” “The mandala as a gift of nature,” “The mandala as a message from the environment,” “The mandala as an expression of Nature’s wisdom,” “The mandala as a union of subjects” or “The mandala as my personal ‘mirror” etc.

FIGURE 1 | The mandala made by 72-year old woman and explained as a symbol of her experience related to aging.

There are many ways to create such mandalas. They can take a circular form constructed of botanical arrangements (Montgomery and Courtney, 2015) and can be made up of different botanical ephemera enclosed in some vessel or bound together in the fascicle or wreath. An example of creating such a mandala as a form of botanical arrangements related to the subject of aging is visible in artwork made by a 72-year old woman who participated in the eco-art therapy group session (Figure 1). Though the session itself took place indoors in Manhattan, New York, the participants were encouraged to use various botanical ephemera that had been found in Central Park by the team leader and then brought to the session. Some additional greenery had also been purchased at one of the nearby markets. At the beginning of one session, the therapist gave the group the chance to explore and seek out any natural materials available and then to select and use some of them in order to create a small personal green mandala. The therapist recommended that participants use cardboard circles up to 25 cm in diameter as a holding space for their botanical arrangements.

Upon completing her artwork, 72-year old woman commented it in the following way:

‘I could say that it was an organic and unconscious process, led by the textures and colors of the materials. I was aware that it was a bit “off-center” in that it didn’t have the usual symmetrical form of a traditional mandala. I actually enjoyed that it seemed to ‘flow’ off to the right and was a bit whimsical and light. It also has a strong feminine quality which pleases me too as I have been exploring that side of myself. It feels grounded and also possesses a quality of releasing and flowing; this mirrors my life at the moment. I have enjoyed the tactile and sensorial experience of working with the natural materials even though the workshop itself was held in a rather sterile interior and urban environment.

I find my mandala to be a good representation of the complex meanings related to aging. I can refer it to Wabi-Sabi, beauty found in the simple, imperfect, old, worn, weathered objects and natural forms. These qualities of “beauty consciousness” that were revealed through the process of creating my green mandala can assist us in seeing beauty in the older human being and can also guide us toward recognizing this same beauty within ourselves as we age. This aesthetic form and this philosophy of life can help us to become aware of aging as a creative act...’

Another example of using the mandala as a form of botanical arrangement which relates to self-perception can be seen in the creative activity of drug and alcohol abusers who participated in interactive art therapy as a part of their rehabilitation program at a specialized day center unit in St. Petersburg. The group conductor encouraged the participants to walk in a park close to the center during the month of September in order to search for natural materials. Later, members of the group created botanical arrangements in the studio by arranging their findings on paper plates.

The group conductor’s idea was that, through the use of some environmental tasks, clients could be facilitated to move into a more open space as a newly symbolic representation of their more autonomous functioning. This activity also helped patients to frame and reframe their self-perceptions, to find meaning in the environment and to appropriate and personalize it. The conductor encouraged participants to work with either an open-ended format (with no particular topic chosen beforehand but simply a spontaneous response to the environment where they chose any natural objects that they found attractive or meaningful), or on the focusing on a topic as “Self-image object”. While taking a walk outdoors, group members could ask themselves ‘Is there some natural object (or objects) in the environment that I feel connected to, have some affinity with, or which can represent my personality?’

On presenting his creation (Figure 2), one of the participants (aged 36) describes how this figure is associated with his life in the last few years – a time when he has perceived himself as running in a circle. He believes, however, that a small break he noticed at the top of his mandala may signify his overcoming his addiction and beginning a healthy new life. He associates acorns with the potential for new growth.

A mandala can also be viewed as an environmental installation or construction, for it shares certain similarities with megalithic creations and contemporary artists’ environmental or eco-art projects, gardens, labyrinths and other ‘green spaces’ as well as circular ‘homes in nature’ used for centering, healing and contemplation.

FIGURE 2 | Botanical arrangement which represents self-perception of one group member.

In sessions involving creating the green mandala, a mindful interaction with the natural environment and forms is the most significant component of such a process. It can be a means of connecting the symbolic forms of art and language with the participant’s immediate physical experience of the natural world (the life process). Creating the green mandala (and other such related activities) can be considered as a means of developing both a somatic awareness and an embodied sense of self in one’s relationship to the environment. This effect is more obvious when clients’ involvement in outdoor activities is combined with both mindfulness and certain body-centered exercises and when emphasis is placed on meditative journeys or path-working as a form of mini-pilgrimage in ‘the green area’ and is subsequently accompanied or followed by green mandala making.

An example of such a creative process can be seen when an environmental mandala is made during the continuation of an environmental mindfulness-based art therapy session (Peterson, 2013) which included a meditative journey taken by a 33 year old femals psychologist. into an institutional green area. She also used a selection of natural materials She participated in the session with other professionals; this group’s goal was to learn ways of developing self-regulating, stress-management skills and mindfulness techniques based on their creative interactions with the natural environment.

At the beginning of one session, a therapist offered a group the possibility of spending one hour outdoors in order to explore the institutional environment of the community center where sessions were taking place. This was an enclosed field with a sports ground, some wild plants and apple, pear and birch trees. The therapist explained that the participants were allowed to select and use any types of organic materials available on the institutional grounds – these included vines, leaves, fruit, branches, and seed pods, wild flowers and other botanical ephemera. Members of the group could also use stones, soil, sand and water.

Participants were encouraged to take a meditative journey through this environment and to find some natural materials and objects that they could then arrange as a small personal mandala. The therapist recommended that participants use small ceramic containers, plates or cups up to 12 cm in diameter as a holding space for their botanical arrangements. They also encouraged the participants to find some place within the environment to install their creations and to arrange the surrounding area, if need be. Later they were invited to present a brief performance – a ritual in the environment – and to interact with their green mandalas as meaningful objects. This part of the session was subsequently followed by participants sharing their experiences and discussing the meanings implied in both their creations and in their performances.

When the group participants completed their green mandalas and were ready to perform in the space where they had installed their creations, a 33 year-old woman performed a kind of a ritual. She invited the group to join in her ritual by following her as she slowly moved around her green mandala which had been placed on the ground. She then stopped and sat on the ground in front of her creation and made some movements with her hands as if she were expressing her reverence to the space and her creation. When she finished her ritual she explained:

“I want my green mandala to be included in the living environment. I’ve chosen a place in the middle of this space encircled with blue chicory flowers. I need a heavenly color. You can see the two apple trees standing from the both sides of this space. I noticed a little spot in the middle and created something like a personal shrine putting my vessel of the green mandala here.

I also put few stones, apples and pears around it in order to mark boundaries. It is important to provide a variety of live forms and biological diversity since this provides endurance for the ecological system. I put water in the vessel and sprinkled water around it. If you come closer you can see ants, spiders and other insects running. All of them are inhabitants of this space and are happy to find that I have left some food for them.

I put a little stone in the vessel too. It is a traditional Japanese symbol of mountains. If there is no any natural rock or hill in the garden people bring stones to signify rocks or mountains. You can see that my green mandala includes a mountain in the form of a stone and lake in the form of water.”

Another participant, a 37 year old man, a school teacher, commented on his experience in the following way:

“I intuitively searched for natural materials for my green mandala in the beginning, and recognized what my creation means later. I’m astonished to discover that nature provides such a great variety of forms and it is very creative, but we don’t value that most of the time. It is often difficult to see even a small part of this great variety when we are absorbed in out routine everyday activities. Today I was lucky to notice and explore this variety of natural beautiful forms and colors abundant even in this small spot of land. You can see the apple in the center of the composition surrounded with water, soil, stones and many flowers and herbs. Everything is included in the small plate of my green mandala. I put my creation in the center of the hatch which symbolizes a circle of our daily routine.”

FIGURE 3 | Group participant performing her ritual in front of her mandala installed in the space.

A 42 year-old woman, a university teacher, invited people to stand in the circle and pass her green mandala through their hands. She said:

“I was sitting on the ground watching the environment around me in the beginning. At certain moment I got a feeling that I’m dissolving in nature. When I stood up and started to search for natural materials around I noticed small plants and shoots. All of them are so beautiful, tiny, and wonderful, but I didn’t notice that before.

It was a spontaneous process of selecting natural forms that I found most interesting and attractive for me in the beginning. I didn’t want to rip and destroy plants so I preferred to take the whole plants including their roots and transport them into the environment of my green mandala. You can see the two little plantains inside. I planted them in the soil that I’d put in the vessel and sprinkled them with water. These plants can grow now. Everything is so small and has a certain Japanese quality. This evokes a special feeling. I felt that when I was making my green mandala. It serves as a small hologram of the world.

FIGURE 4 | Green mandala created by 37 year old man – a school teacher.

FIGURE 5 | Green mandala created by 42 year old woman.

When I completed my creation I started to walk around carrying my creation in a meditative state of mind with me. I realized that I can take a small part of this beautiful wonderful natural environment in my hand and even share it with other people. I can pass my green mandala through the circle of people now. You can feel its warmth created with my hands and with the little candle burning in the middle. Later, I can put my creation somewhere. I can separate from it now and know that it needs separation too. It has its own life now and it is free. Perhaps I’ll take it with me and put it on a table during lunch time.”

Conclusion

Both the ecological and environmental perspectives on the therapeutic application of the mandala presented in this article help us to understand and define it as an expressive/creative tool which brings both the arts and nature together to provide therapeutic, health-promoting effects. The human inclination to create circular symbolic forms of natural materials (often in relation to the natural environment) can be considered from both an ecological and environmental viewpoint as an expression of the human instinct to create a mutually supportive relationship with nature. This inclination can be explained, in particular, via the biophiliahypothesis which postulates a pervasive attraction between humans and nature in all its differing mineral, plant and organic forms. It focuses, too, on circular structures as representations of a healthy and contained life.

The mandala as an ecological artwork made from natural materials and/or in nature serves as a special instrument for providing physical and psychological healing as a result of a positive biophilic human relationship with nature. As with any other method or instrument applied in eco-psychology and eco-therapy such mandala-making is based not only on the premise that the health of the planet impacts our health but also on the notion of collective synergy between the well-being of communities, individuals and the environments in which they live.

Creating the mandala as eco art therapy practice can be a viable expression of the art of biophilia (Kopytin, 2016), a form of creative activity in and with natural environments (green spaces) and rooted not so much in the need of creative self-expression in the traditional sense of this word, but on a strong motivation to support and serve nature and life. The act of creating such mandala can be understood as an ecological form of personalization of the environment which supports the establishment and further development of Eco-Identity, an aspect of self- perception and of self-attitude implying ones’ feeling and understanding of a vital connection to nature, the eco-system which implies one’s responsibility towards and stewardship of nature.

The brief case studies presented here illustrate a variety of ways in which the production of the green mandala can be factored into the therapeutic processes of different client groups, This creative action can take place either indoors or outdoors using mostly natural materials and forms. These vignettes demonstrated that the process of creating the green mandala occurs in several clearly delineated phases: nature-connecting, preparation, experience and debriefing of the experience (Scull, 2009). These examples also indicate that creating such mandalas as an eco art therapeutic activity (when clients are safely grounded in some natural space and forms) helps them to perceive themselves in an holistic way, and allows them to view their mandala as the container of embodied sensory, perceptive, emotional, imaginative, symbolic and spiritual experiences. This allows the participants to come to a more balanced and healthy understanding of themselves and their relationships.

About the Author

Alexander Kopytin is a psychiatrist, psychotherapist, professor in the psychotherapy department at Northwest Medical I. Mechnokov University, head of postgraduate training in art therapy at the Academy of Postgraduate Pedagogical Training at St. Petersburg, and chair of the Russian Art Therapy Association. He introduced group interactive art psychotherapy in 1996 and has since initiated, supported, and supervised numerous art therapy projects dealing with different clinical and non-clinical populations in Russia.

References

Diehl, E. R. M. (2009). Gardens that heal. In L. Buzzell & C. Chalquist (Eds.), Ecotherapy: Healing with nature in mind (pp. 166–174). San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books.

Gregory, L. A., Fried, Y., & Slowik, L. H. (2013). “My space”: A moderated mediation model of the effect of architectural and experienced privacy and workspace personalization on emotional exhaustion at work. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 36, 144–152.

Heimets, M. (1994). The phenomenon of personalization of the environment. Journal of Russian & East European Psychology, 32(3), 24–32.

Hillman, J. (1995). A psyche the size of the Earth. In T. Roszak, M. Gomes, & A. Kanner (Eds.), Ecopsychology. Restoring the Earth, healing the mind (pp. xvii–xxiii). San Francisco: Sierra Club Books.

Jung, C. (1973). Mandala symbolism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. (1976). Symbols of transformation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kopytin, A. (2016). Green studio: Eco-Perspective on the therapeutic setting in art therapy. In A. Kopytin & M. Rugh (Eds.), Green studio: Nature and the arts in therapy (pp. 3–26). New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Montgomery, C. S., & Courtney, J. A. (2015). The theoretical and therapeutic paradigm of botanical arranging. Journal of Therapeutic Horticulture, 25(1), 16–26.

Peterson, C. (2015). “Walkabout: Looking In, Looking Out”: A Mindfulness-Based Art Therapy Program for Cancer Patients. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 32(2), 78–82.

Scull, J. (2009). Tailoring nature therapy to the client. In L. Buzzell & C. Chalquist (Eds.), Ecotherapy: Healing with nature in mind (pp. 140–148). San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books.

Wilson, E. O. (1984). Biophilia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wilson, E. (1993). Biophilia and the conservation ethic. In S.R. Kellert & E.O. Wilson (Eds.), The biophilia hypothesis (pp. 31–40). Washington, DC: Shearwater Books/Island Press.