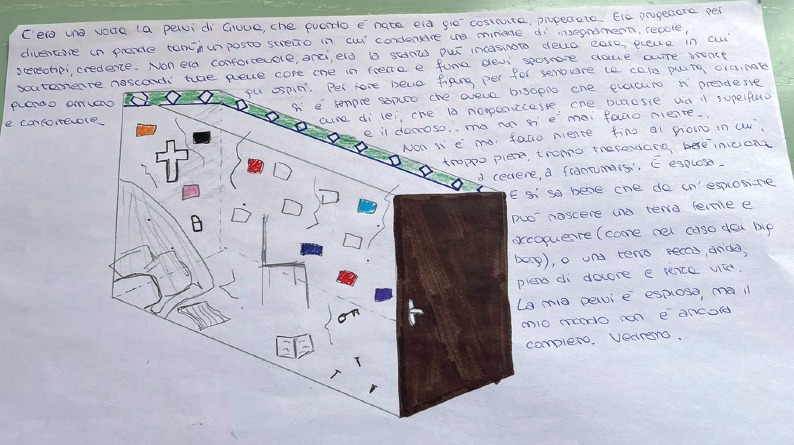

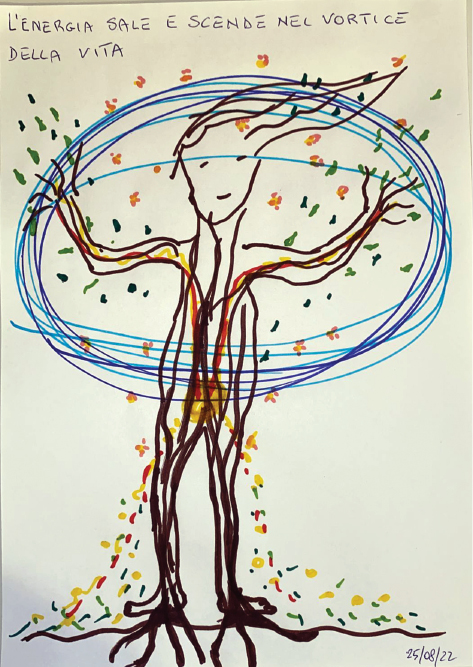

FIGURE 1 | Image taken from the experience of G., who was invited to draw her own pelvis and tell its story. The pelvis is represented here as “the messiest room in the house.”

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2023) 9(1):77–93 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2023/9/7 |

What Flows Underneath the Disease

疾病下方的流动

Art Therapy Italiana, Italy

Abstract

This article aims to explore the potential of dance/movement therapy (DMT) and creativity in supporting patients with chronic pelvic pain. It investigates the impact of a non-judgmental environment on the development of coping and self-compassion strategies; the potential of using DMT’s tools and art in general to explore, in a safe and creative container, one’s relationship with the disease and the meaning it has taken on in one’s personal history and the rediscovery of one’s psycho-bodily resources to listen to and actively dialogue with one’s pain. This article is based on a study conducted in two therapeutic groups of four women each. As the project was born during the COVID-19 pandemic, the meetings were conducted online and lasted approximately 2 years.

Keywords: chronic pain, vulvodynia, dance/movement therapy, self-compassion, dialogue with one’s pain

摘要

本文旨在探讨舞蹈运动疗法或 dance/movement therapy(DMT)和创造力在支持患有慢性盆腔疼痛的患者方面的潜力。它调查了非评判性环境对应对和自我同情策略发展的影响;使用DMT的工具和艺术探索个人与疾病的关系及其在个人历史中所代表的意义,在一个安全和有创造性的容器中;以及重新发现个人心理和身体资源,以便倾听并积极对话自己的疼痛。本文基于在两个治疗小组中进行的研究,每组有四名女性。由于该项目在COVID-19大流行期间诞生,因此会议是在线进行的,并持续了大约两年时间。

关键词: 慢性疼痛, vulvodynia (阴道痛), dance/movement therapy (舞蹈运动疗法), 自我同情, 与疼痛对话

Numbers Related to the Disease

Worldwide, the percentage of women suffering from chronic pelvic pain ranges from 14% to 32% (Mathias et al., 1996). Vulvodynia affects 6% of women worldwide (according to some statistics, up to 20%), regardless of age or ethnic group (Vieira-Baptista et al., 2018). Women with chronic recurrent cystitis represent 1 in 4 of those who have experienced a single episode of cystitis in their lifetime, ranging from 40% to 60% of women worldwide (Franco, 2005).

Although these pathologies differ significantly in their symptomatological manifestations, they are united by a chronic course, effect on an area connected to intimacy and female identity, non-uniform and expensive treatment protocols, and a diagnostic delay—due to the scarce knowledge of the doctors of this type of pathology—of approximately 4 to 7 years, depending on the geographical area of origin (Graziottin et al., 2020; Harlow & Stewart, 2003).

Moreover, these pathologies are linked by the impact they have on the patient’s life, bringing physical disability, limitation of everyday activities, sexual dysfunction, and psychological stress (Friedrich, 1987). This impact often leads to a sense of helplessness in patients, whose sense of agency and resilience is threatened by the lack of effective treatment as well as by the lack of medical knowledge about the condition and the feeling that their symptoms are not believed—a feeling that affects relationships with both the specialist and other people: 45.1% of women who see a specialist are accused of somatization or exaggeration of their symptoms (Nguyen et al., 2013).

Introduction

For as long as I can remember, my body has manifested discomfort. Fatigue and chronic pain have been with me since early adolescence, a time when they were labeled “growing pains.” Over the years, they have taken the form of recognizable diagnoses: chronic pelvic pain, vulvodynia (an inflammatory syndrome of the vulva and vagina whose cause is neuropathic, not infection), and chronic cystitis caused by muscle contracture.

I have found that many women suffer from the same disorders and receive the same diagnostic framing, with slight differences determined by the areas most affected by the symptoms (vagina or bladder) and the professional background of the referring specialists (gynecologist versus urologist), who use different definitions for the same type of disorder.

The path to recognize these conditions with the “label” of a diagnosis has been slow and arduous. My age when the conditions began, combined with the limited medical knowledge that existed among professionals until about 10 years ago, contributed to the underestimation of problems that became aggressive, chronic, and debilitating.

I fought with my family to make them understand that pain was not an excuse for not going to school. I fought with the various specialists I saw to make them acknowledge the existence of pain, a condition that, being impossible to “measure,” is difficult to prove. Being forced to undergo invasive examinations that inevitably led to neither confirmation, denial, nor resolution left me feeling violated and eventually taught me to distrust the very world that, on paper, had the power to help me.

Having suffered for about 15 years, I have had the privilege of witnessing the birth of a different understanding of this type of disorder. The diagnosis of “it’s all in your head”—which many women before me can testify to receiving—has slowly been replaced by a much less holistic and more medicalized vision: musculoskeletal tension states, environmental versus genetic causes, alterations in chemical mediators such as neurotransmitters or hormones, previous systemic diseases. Each of these possible triggers has led to a different therapeutic approach.

However, the possibility that these were “psychosomatic pathologies” continued to be raised, despite numerous scientific studies and all the awareness-raising activities carried out by patient associations. After all, a disease of psychic origin is a disease that does not exist or at most exists as a mental disease: a disease that is denied, despite the effects of pain.

The existence of a possible psychic component to my condition exacerbated my sense of failure, incommunicability, and guilt. I felt the need to explore these feelings, which would certainly not lead me to discover the origin of the disease, but would help me find my true voice and personal narrative within a universe of people who had always spoken for me. I could not run away from the pain, but I could regain an inner place from which to observe my wounds without judgment by claiming my right not to embark on treatments that made me feel more wrong and vulnerable than the disease itself.

To date, the treatments offered to those diagnosed with chronic pelvic pain have been protocols combining very low doses of tricyclic antidepressants, vaginal anxiolytic vials applied daily, supplements to restore the bladder mucosa, and rigorous pelvic floor rehabilitation sessions with osteopaths or specialized physiotherapists (Reed, 2006). These protocols are usually repeated for years. I leave it to the reader to imagine this therapy’s economic impact, as well as the sense of violation to which every patient is subjected.

This brief introduction of a personal nature is the basis of my motivation in creating the dance/movement therapy (DMT) project that is the subject of this study, dedicated to women diagnosed with chronic pelvic pain, vulvodynia, chronic cystitis, and pudendal neuralgia.

I felt a need to provide a non-threatening place where women like me could talk about and deal with their pain. Goals such as feeling seen and recognized seemed to go hand in hand with creating a positive relationship with one’s physicality. I saw the need to acknowledge the fatigue and impact on the psyche of such invasive and protracted therapies, sometimes without satisfactory results, and I thought it was important to contain the sense of limitless loneliness that an illness “that does not exist” often brings.

Acquiring the proper language of DMT allowed me to observe and narrate the disease from a different angle. Pelvic contracture, increasingly considered to be the determining cause of chronic cystitis and vulvodynia (Hartmann & Sarton, 2014), had taken on the recognizable manifestation within Laban’s framework for effort1 of a high-intensity bound flow2 (Laban & Ullmann, 2021; Loman & Merman, 1996).

DMT ascribes a profound psychological significance to the flow: It is defined as an “emotional factor” (Di Quirico, 2012). I felt that pelvic contracture was trying to express the need to protect oneself from feelings of insecurity, anxiety, and danger by establishing a state of tension and control. I was fascinated that, in my personal experience, no medical reference had ever made this association, even on a symbolic level.

I wondered if focus on the perception of the patient’s muscle tension flow (working on the polarities “free” and “bound”) might help future participants in my sessions gain emotional awareness of their inner world and how it is reflected in their bodies, perhaps contributing to learning how to release accumulated tension.

COVID created the perfect and necessary conditions for me to finally begin this research. With the day centers where I carried out my activities as a dance/movement therapist closed, I needed to find new places and projects in which to invest.

Creating online meeting spaces seemed an appropriate response to the growing need for access to mental wellbeing services. Another advantage of online therapy is the reduction of geographical distance, no small benefit for those forced to travel hundreds of kilometers to see a specialist. I therefore contacted one of the most active associations for women with urogenital diseases in Italy, Cistite.info, to activate my projects.

The following describes my experience as a dance/movement therapist in a virtual environment dedicated to the support of women with chronic pelvic pathologies, developed over a period of almost 2 years.

The Project

As soon as the association informs its members of the existence of my project, I am inundated with requests to participate and questions. The condition affects adolescents and postmenopausal women, wives, divorcees, and single women. This transversality is reflected in the sample of women who have expressed an interest in the journey I am proposing.

I select patients based on the chronological order of the emails, and I proceed with the introductory interviews. In addition to the routine questions, I ask whether the patients have any memory of the onset of the pain and whether they can relate this manifestation to any event.

Almost all patients clearly identify a particular episode that is related to the onset of symptoms, and the seriousness of these events is something that I cannot consider irrelevant. Episodes of sexual violence in early adolescence; surviving a motorcycle accident, yet helplessly witnessing the death of one’s boyfriend who was driving; losing both parents as a child to degenerative diseases; growing up in a dysfunctional home environment with an abusive, hoarding father and a subservient mother; spending one’s adolescence caring for one’s dependent mother until death…. These are the narratives that begin to penetrate the setting.

I am not trying to support the idea that there is always a psychological trigger behind this type of pathology (this would only confirm the dominant stereotypes that contribute to phenomena such as diagnosis delays and the stigma of “it’s all in your head”). Rather, I am stating the pervasiveness of the chronic pain/traumatic stress correlation, a combination so strong that it could not be ignored and deserved special attention in conducting and structuring my practice.

Today, I still feel that exclusively medical and exclusively psychoanalytical views can be polarizing and hinder patients’ ability to weave a complete and integrated narrative of their lives.

Introduction to Groups and Meeting Structure

Upon completion of the introductory interviews, two distinct groups were formed, each comprising four members. The first group features a diverse age distribution, including a 21-year-old, a 55-year-old, and two 35-year-olds. The second group also exhibits a varied age range, with a 31-year-old, a 56-year-old, a 45-year-old, and a 46-year-old member.

Pain did not prevent the participants from taking part in the meetings: therefore, the number of participants did not fluctuate throughout the entire process. However, one participant decided to discontinue the activity and resume it a few months later.

The Impact of Pain on Methodology

Meetings are scheduled on a weekly basis, with a predetermined duration of 1.5 hours. Throughout the research project, the meeting frequency remained consistent, with the exception of interruptions of 1 or 2 weeks that coincided with vacation periods. This regular schedule was maintained to provide participants with a stable and reliable holding environment.

Each meeting is divided into two parts: verbalization and creative proposal (movement and/or creative proposal of an artistic/expressive nature). Each part lasts approximately 45 minutes. These two parts alternate as follows and are easily recognizable to each participant, in order to lower the general anxiety toward the proposed activity.

Verbalization occurs both at the beginning and end of each meeting. At the beginning, verbalization is dedicated to collecting the general moods of the participants and understanding the overall level of suffering in the group. This information is used to shape and guide the creative activities proposed during the meeting. At the end of each session, verbalization is dedicated to collecting and processing the experiences, sensations, thoughts, and images that emerged following the creative activity.

As a therapist, I felt that flexibility and creativity were required to adapt the creative proposals to the general level of energy and well-being present in the group. This means not denying the impact of pain, but rather integrating it within the process, by understanding how it shapes the actual physical, creative, and expressive possibilities of each participant in the here and now.

The level of intensity with which pain presents itself in meetings can be severe, mild, or completely absent. When pain is present in a severe form, the body often appears unreachable. Therefore, activities such as drawing, creating “sculptures” made from common objects, writing tales, or autobiographical narration were preferred. When pain presents itself in a mild form, the body can be contacted, although the symbolic-expressive components of movement appear inaccessible to the participant. The proposals are therefore oriented toward offering containment of the experience of suffering: relaxation is encouraged through experiences of guided self-listening or self-massage. When pain is absent, the proposed activities involve the body in a more active, expressive, and symbolic way, through invitations to create dances, single and group choreographies inspired by specific topics.

Due to the online nature of the meetings, the use of music was avoided in order to prevent potential technical issues from affecting the participants’ process.

The theme chosen for each meeting (whether related to the area of movement, drawing, or creativity in general) is always consistent with the topics brought to the session by the patients. The level of pain may not be homogeneous within the group; the therapeutic challenge is then to identify an activity that can involve both participants with a relative sense of well-being and those who are suffering. It is fundamental to propose activities that can be carried out by all the group, in order to reduce the sense of helplessness and inefficacy induced by the disease: in other words, strengthening the sense of agency of the participants.

The group process will be illustrated below, addressing the above-mentioned elements in a more in-depth sense. Although the group—and the proposed activities—have undergone an evolution that has allowed the body to finally become the protagonist of the activity, the physical involvement of patients has continued to fluctuate throughout the whole process, due to the onset of pain.

Phase 1: Get Acquainted with the Body

The first phase is devoted to entry into the discipline and the creation of a basic trust toward the other participants and the therapist (Bion, 1961), so as to help the patients to gradually abandon prior forms of bodily defenses.

The content that patients verbalize at this time is mainly about the symptomatology they experience. There is no real room for emotions, except for some reactive depression caused by their physical condition or frustration at the failure of yet another drug therapy.

I am amazed by the feelings I get from our first sessions. These patients’ physical perception of themselves and their relationship with their symptomatology is completely delegated to the outside world. It is the urologist, the gynecologist, the physiotherapist who knows their real psychophysical state of health and who is responsible in their place. It is as if they have lost the right to speak on their own behalf.

Soon the setting becomes a container for the history of physical pain (worsening and improvement). There seems to be no space for narratives that do not propose symptomatology as the only theme. At certain moments, the descriptions of the appearance of a new bacterium in the urine are so devoid of emotional involvement that talking about pathology seems like a form of defense to avoid talking about oneself. But this does not alter the fact that the patient and the pathology are indistinguishable in this moment: “I am the disease and the disease is me,” they seem to communicate.

At this stage, each body is locked into the defenses it uses most often. The patients’ movements seem to be suffocated by rigidity. There is a kind of inhomogeneity, a disharmony in the group’s movements. Participants are locked in their shells: some use a bound flow with high intensity (which results in a kind of freezing), while others use a flow so neutral that they appear drained and inanimate (Laban & Ullmann, 2021).

The therapeutic challenge of identifying activities that can homogeneously produce a beneficial effect—as well as the need to hold together opposites that tend to repel—becomes increasingly pregnant and urgent at this point.

Lowering anxiety toward the activity I propose is necessary for deeper involvement, as well as the consolidation of a “group identity” or sense of belonging to the group (Schmais, 1998). Drawing on studies related to Porges’ (2011) polyvagal theory, which emphasizes that living in a constant state of physical insecurity prevents fully experiencing social engagement and relationships, I propose structured activities designed to restore basic physical security and a psycho-corporeal alliance, fostering the perception of being in a safe place and promoting connection one with the other.

I begin each session with an invitation to listen to one’s sense of weight and breath in order to regain a sense of grounding and security. In the long run, I hope that the patients will acquire bodily resources of self-regulation. Small guided bodily listening experiences are followed by moments of graphic transition and verbalization to reinforce a sense of interoception: How was your body today? What changes, if any, did the exercise produce? Creativity is in the background at this stage; I feel that the group has not yet experienced an alliance and a sense of safety that is deep enough to allow them to tap into their expressiveness without feeling vulnerable.

I make a point of using positive imagery that they can return to after the session. For example, I propose moments of “inner massage” in which patients are asked to become familiar with each part of the body and to move it with the intention to release tension and “restructure” the whole. I propose dances of the different parts of the body as a starting point for the “dance of the whole body.” In this process, I repeatedly invite patients to feel and internalize a sense of interoception and self-efficacy: How does each part move? How do I “feel” each part, and what are its needs? How can I take care of it?

I also work to create a sense of group identity and group belonging. In this phase, I support different formations, like smaller groups and pairs, in order to allow the group to separate and come together as needed, proposing activities to tap into creativity without overly involving the body. The body is in such a defensive state that it is unable to listen to and explore the experiences that inhabit it, and I am very wary of generating feelings of inadequacy and activating other defenses. Being online also forces me to be doubly careful: if a proposal has an effect that is too strong and unexpected, containing a dysregulation would probably be more complex.

Sometimes I have the feeling that aggressive impulses are moving among the participants, with the unconscious intention of destroying the group. At this stage, they make extensive use of the defense of reactive formation: the fear of coming into contact with an other is transformed into verbalized and exuberant pleasure in being together, as well as overinvestment in the setting itself. My role is perceived with ambivalence; I represent both threat and salvation. However, in order to receive “healing,” the group needs to ally with my salvific capacity and remove its mistrust toward me. The group perceives me as being endowed with the power to defeat pain, expressing the basic assumption of dependency as theorized by Bion (1961). The illusion is so strong that it causes the disappearance of the symptomatology for a time, an event that the patients easily attribute to the “powers” of DMT.

Phase 2: The Relationship between Self and Disease

The group has been meeting for a few months now—long enough to have disinvested in the thaumaturgical power of the setting. Patients continue to shift their need for dependence, and therefore the possibility of triggering any form of improvement outward. When they realize the inability of DMT to take full responsibility for their wellbeing, they begin exploring new therapeutic avenues.

The protection of the setting from the interference of new paths (like personal psychotherapy, changing doctors, and tantra and belly dance courses with a “therapeutic” orientation) thus becomes an urgent, challenging goal. Gently but firmly, I resist the patients’ aggressive urges, more recognizable and manifest than in the initial phase, to turn our sessions into a celebratory scoreboard of successes reached elsewhere. I become the target of devaluation and the projection of the patients’ sense of inadequacy and ineffectiveness.

However, as Yalom and Leszcz (2020) point out, this manifestation of hostility and consequent discounting of my role as therapist is necessary for the beginning of a new phase: the evolution of the group into a compact unit. The initial fusional fears have now given way to a desire to connect authentically with others. Finally, the group expresses the accomplishment of a state of belonging and sisterhood that allows the emergence of reciprocity, integration, cooperation, and mutual support.

At the same time, the anxiety caused by my proposals has been effectively contained. Presence and physical involvement are now permanent elements of the sessions. These premises allow me to fluidly introduce the subject of the relationship with the disease and its meaning, without leading to places of fear that are difficult to manage.

My proposals gradually shift from the more directive and structured aspects toward the symbolic and imaginative: Is it possible to represent the disease with a movement or a gesture? What are the needs, feelings, emotions, and images associated with the disease? Is it possible to represent or draw pelvic contracture? What about the bladder? If I were to write a fable about my bladder, what form or narrative would this story take? Finally, the patient’s creativity becomes the protagonist of our sessions.

This is an important moment: patients spontaneously begin to associate their traumatic history with their disorders. The girl whose father is a serial hoarder draws her bladder as “the messiest room in the house,” saturated with her parents’ stuff and “with teachings, rules, stereotypes, and beliefs” (Figure 1). For her, the bladder is “the room in the house where, in order to look good and make the house look clean, you hide the dirt so that the guests cannot see it.” These reflections are the prelude to a process of differentiation from their physical condition. The statements “I am not cystitis,” “I am not vulvodynia,” and “I am not my pelvic contracture” begin to appear, used with increasingly self-affirming power.

FIGURE 1 | Image taken from the experience of G., who was invited to draw her own pelvis and tell its story. The pelvis is represented here as “the messiest room in the house.”

Slowly and spontaneously, the group weaves connections between the disease and the experiences it conceals and brings. The pelvis is associated with words such as “threat,” “fear,” and “need for control.” Pelvic contracture is universally recognized as a difficulty in letting go. Rigid, extreme control of the self seems to be a way of pushing difficult emotions out of consciousness. The connections that emerge between the disease and its symbolic/emotional aspect enable the group to access a different narrative of the self.

This is probably the most important offer that DMT can make at this stage: the weaving together of a psycho-consciousness, the awakening of a new sensitivity to listening to the self, the promotion of a non-judgmental attitude toward pain. What the patients experience is the possibility of offering symptomatology, pain, and pathology a space for expression, which manifests itself through new movements, individual and group choreography, and graphic transitions (the drawings made at the end of each dance, which act as a “transition” from physical experience to spoken language). The symbolic dimension also enters into the group’s narratives and dances, which finally finds fertile ground for development.

Physical pain is no longer an enemy from which one waits to be rescued by external intervention, but rather a clue that signals the need to take time for oneself, to stop, to slow down, to regain a space of existence. This coincides with the reappropriation of one’s agency and the possibility of creating and inhabiting a space for reflection in a participatory way, which enriches one’s self-understanding and awareness of the vicissitudes linked to one’s family history.

The parts of the self that the DMT activity has brought to light now have the possibility of being contacted, named, and finally integrated by the patient. They replace the emptiness, defeat, and incommunicability that the pathology seemed to involve. In this context, the symptom changes from a “mere” physical manifestation to a glue between consciousness and deep, otherwise inaccessible experiences. This is particularly evident in the patients’ verbalizations, which are colored by rich and multifaceted emotions and images, in contrast to earlier when they were very detailed in terms of symptomatology but sometimes lacked emotional depth.

After a few months, however, things change. If at first the groups welcomed the creative exploration of their pathology as an interesting opportunity for growth and self-analysis, slowly a “saturation point” is reached where further development seems impossible. Unfortunately, understanding what lies behind the physical symptoms does not always coincide with physical healing. On the contrary, it brings out painful, difficult, denied aspects of themselves that can no longer be silenced or avoided.

They also experience the disillusionment of discovering a pathology that persists despite having been listened to, understood, and symbolized. The great commitment involved in looking within does not lead to real improvement, generating frustration. Understanding the relationship between anxiety and pelvic contracture does not help the muscles to relax. Pain has a chronic course, and although it can be considered an ally or friend in moments of lesser intensity, it becomes deafening in moments of greater vulnerability.

I feel like I am going round in circles, and I experience the overwhelming frustration of not being as helpful as I would like. Under the surface, a new process is beginning to manifest. Experiences outside the setting related to daily life beyond the disease are slowly beginning to colonize our sessions. Unlike at the beginning of the second phase, this new content has nothing to do with the interference of other professionals, but rather with the need to share daily life and intimacy. They are small seeds of a new three-dimensionality: from being just “women affected by,” the participants bring the complexity of being “fully themselves” to the setting. This has cathartic value; participants begin to take on a real identity by talking about their families and activities beyond the disease.

Talking about “emotional intimacy” in relation to a disease that affects so much of the most intimate aspect of physicality inevitably brings sexuality into the picture. It is a theme that, from a latent state, becomes increasingly dominant.

Phase 3: The Conflict—What Flows Underneath the Disease

Words such as libido, sexuality, and eroticism become increasingly prevalent in the setting. Patients verbalize their desire to form a stronger bond with their partner or the need to explore their sexuality in new ways.

In the dances, the pelvis and the pelvic area take on a new meaning. It is possible not only to make contact with this part of the body—“empty” and forbidden at the beginning of the process—but also to give it a leading role.

Sensual dances, dances of femininity, dances of fertility, and dances of the vulva are created. In this process, the group reaffirms its alliance and rediscovers the possibility of drawing creative energy from the circle. This is knowledge that has ancient connections with tribal dances and forms of sisterhood, in which giving space to sexuality also becomes the enriching possibility of confronting an important and normally unspoken topic.

However, although revitalizing, this process inevitably confronts forms of anger, frustration, and guilt related to a pathology that hinders the full expression of sexuality. The most contradictory aspects manifest themselves first imperceptibly, then more and more forcefully and recognizably. Joy, creativity, and commitment slowly fade.

The group expresses these more conflicting aspects by splitting into two distinct polarities: some participants move toward a style characterized by high intensity, whereas others seem to switch off, physically deactivate, and lose contact with the more expressive aspects of their relationship with their bodies. Like empty sacks, some patients withdraw from the group and my proposals.

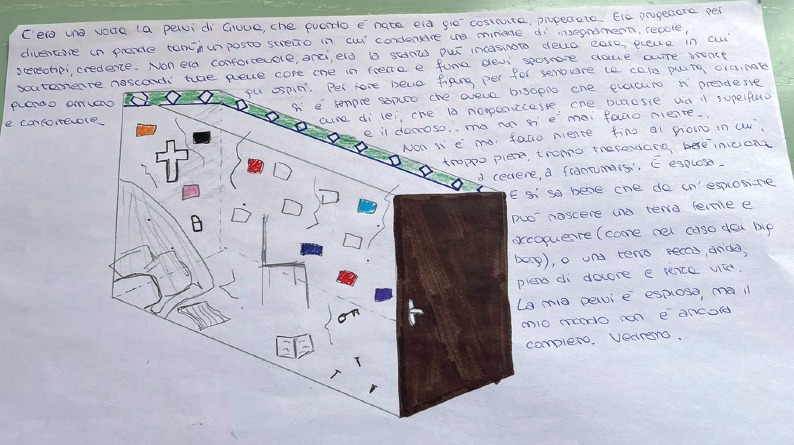

Women whose movement is characterized by high intensity experience a kind of “awakening of the senses,” which leads them to explore new aspects of sexuality and share them within the group. Some patients manifest a peculiar form of gratitude toward the pathology for teaching them a deeper and more authentic form of contact with their sexuality. The latter also report an improvement in their symptoms and even the disappearance of pain (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2 | Drawing by F., belonging to the sub group experiencing an awakening of the senses. The drawing, made at the end of a movement session, shows the following words: libido, joy, sexuality, tantra, pleasure, play, energy, women.

In contrast, those who are stuck in shutdown do not notice any change in their symptoms, but instead take on the burden of impotence, the feeling of being hopeless and deeply wrong. They verbalize that they are not “good enough,” enlightened enough, or courageous enough to grasp the signs of possible transformation. The group container of experience seems inadequate for some more hidden needs that require, in parallel with the body work, a deeper exploration that only an individual course of psychotherapy could offer.

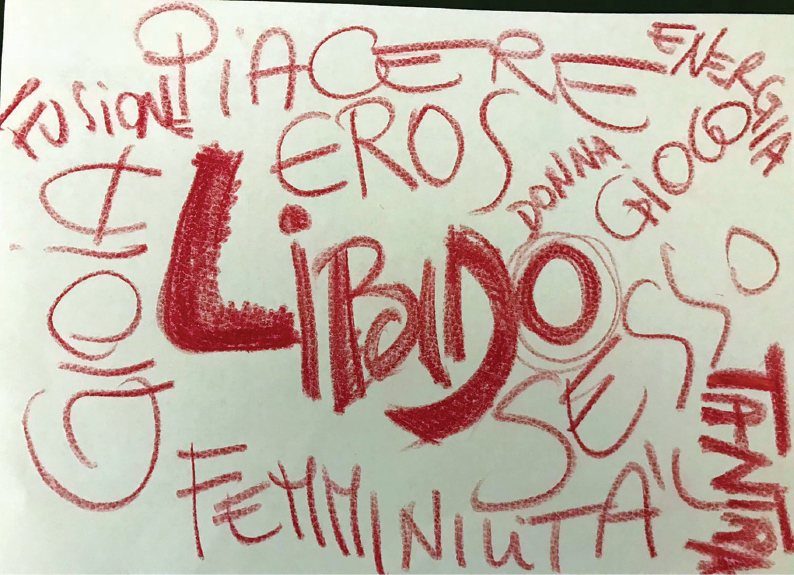

Sometimes, the enthusiasm of the first sub group falls on the second, trying to convince the latter that the solution to pain and disorder lies solely in a “healthier” and more relaxed approach to sexuality. This possibility fascinates and seduces the more withdrawn participants, but it turns out to be yet another false hope (Figure 3). Like the ebb and flow of the tide, I witness continual movements of growth and despair that inevitably break in the appearance of new pain.

FIGURE 3 | Drawing by L., belonging to the sub group of the withdrawn participant, made at the end of a session. The drawing, titled “Having No Choice?,” represents the feeling of being “trapped” by the disease, which had re-emerged in its most debilitating form after sexual intercourse, encouraged by the other participants.

This new dynamic expresses the emergence of roles, which also act as forms of defense, in one’s relationship with the pathology and, by extension, with the self and the environment. Aggressive manifestations and renunciations, feeling omnipotent versus feeling completely powerless, allowing oneself to be invaded by rage and emptied by despair, being a victim and being an executioner, being a dedicated and faithful patient or being rebellious and defiant: it seems impossible to adopt different modalities from those currently used or to perceive any “gray areas.”

My invitations to combine different dances lead nowhere; my invitations to bring the differences into dialogue lead nowhere: the group verbalizes the impossibility of creating new choreographies from such split styles, or else it becomes paralyzed. The conflict seems destined to explode rather than be resolved.

Even the most enthusiastic participants become increasingly despondent. Their dances are emptied of the desire for upward and sagittal movement, domination of space, and urgency; they would rather seek the support of the wall, the floor, or the couch. These patients often lie motionless in front of the screen with their eyes closed. They give me the feeling that I am looking at dead women in a coffin, ready for ritual greetings.

This process is very difficult for me to witness. I feel impotent and unable to imagine any movement or development that could counteract the seduction of death, paralysis, or stasis in pain. I cannot formulate proposals that the group can grasp, so I stop to reflect on my role in the group process.

I understand that the group is expressing the need to feel the setting as a stronger, firmer container. I feel that the activity is now permeated by the urgency to test the new boundaries of the setting and the need to perceive whether or not the “safe space” originally promised exists; in other words, whether I will be able to accommodate and hold together even the most ambivalent, “ugly,” “shameful,” or depressive aspects that each participant brings. I view the stagnation as a question for myself: will I, as a therapist, be able to “live up” to the depth of the material that has emerged? Sometimes I have the impression that this request to feel the setting as a firmer container takes on the characteristics of a challenge (“How much will you be able to hold?”) and that the group, through its resistance, is also trying to manifest its need for autonomy.

It is precisely this last consideration that prompts me to reflect on my role and the nature of my intervention. I become aware of the existence of an unconscious desire in me, which inevitably colludes with the group’s resort to the defense of dependence: I have an immeasurable need to protect the patients from pain, fragmentation, aggression, and self-destructive impulses, which hinder the growth and development of the group itself.

I realize how much my intervention and my directive proposals, although well-intentioned, actually replicated a relational pattern well known to the patients: the doctor who “directively” writes the prescription for medication; the physiotherapist who, better than the patient herself, can interpret and address the needs of a pelvic floor. In other words, I too am the external regulating source whose existence unconsciously confirms the group’s need to depend on a leader.

I limit myself to facilitating a supportive process in which I explicitly ask the participants to offer a “dance of response” to creatively support the most suffering patients. I also began to use the Chase Circle to reshape, contain, and transform the gestures and impulses that I find most problematic into a shared dance. I invite patients to create group choreographies that can show pain, conflict, and stasis, but also rebirth. The impossibility of “holding polarities together” is now obsolete: the group has the full capacity to repair the split, connect opposites, represent the transition between extremes, and build the middle ground within limits. The transformation of the leadership model, giving the group the possibility of self-regulation, finally triggers an evolution.

This process seems to involve and revitalize precisely those patients who, until recently, seemed to be relegated to a passive role. They are the ones who initiate and take charge of a containing process that prevents the others from sinking.

I am witness to a wonderful feminine spring, an alliance of women who are not afraid of their own femininity, unconscious, and shadow parts; women who, having freed themselves from the label of patient, have the strength, grounding, and resources to stand up for themselves and their rediscovered “sisters.”

Phase 4: Body Resources and Conclusion

The group acts for a while as a single, fused body. The participants’ agency and self-help capacity has an incredible regulatory function that goes beyond the setting. The patients finally seem to be free of their need to depend on the other, so much so that they find the impetus to question their lives as wives/partners and make a decision about it.

Slowly, the group seems to have exhausted its exclusive function of containment. The first traces of differentiation appear, but without the urgency and aggressiveness with which they manifested themselves in the initial period. The circle seems to have developed the ability to tolerate and accommodate differences, gently. The large group body returns to being made up of individual bodies, now transformed by the sessions and the process.

What strikes me most about this fourth phase is the emergence of new efforts and styles of movement in the patients. Those who have only used bound flow now seem willing and able to allow themselves the flexibility of freer flow; those who have only used free flow have developed the ability to use bound flow in order to perceive more of their own structure, base, and boundaries. The movements and dances seem more coherent, continuous, and three-dimensional, without “gaps” or hiccups. The patients are now transformed by the encounter with the other and the possibility of experiencing different roles. Those who were confined to an autonomy that had the aftertaste of rejection and loneliness were able to experience the possibility of relying on themselves in times of need; those who were convinced of their own lack of resources and learned helplessness were able to experience their ability to act on their surroundings and support the other participants. In other words, the group learned new models to identify with.

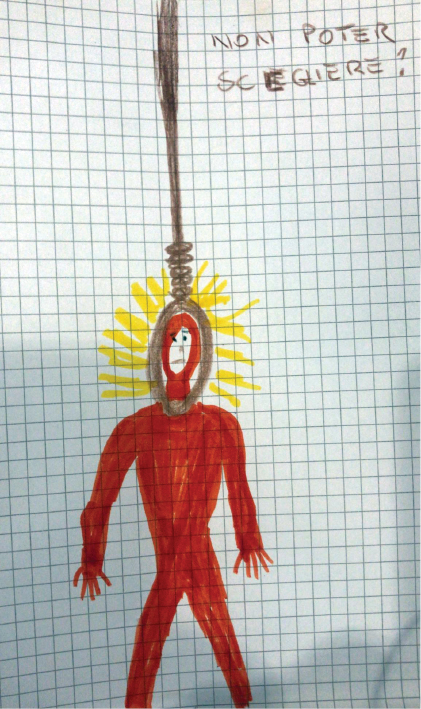

Describing the movement sessions, words such as “wellbeing,” “calm,” and “resilience” appear—this time, in the author’s opinion, experienced with deep emotional sharing and awareness (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4 | Drawing by L., titled “Energy Rises and Falls in the Vortex of Life.” The drawing, which appears very different from Figure 3—also made by the same patient—communicates a strong sense of bodily presence and connection of the parts as well as rediscovered vitality.

Although the pain does not disappear, the patients demonstrate their capacity for self-determination by deciding whether or not to undergo a new course of physiotherapy or medication. The cycle of dependence on external regulation seems to have been broken. Young patients with a very short clinical history and a pathology that is not yet chronic speak of a complete remission of symptoms.

Conclusions

Life seems to flow again. Patients begin to plan their daily lives beyond the setting. Some of them enroll in training courses, others try new work projects, and still others think about changing jobs to better suit their prerogatives and desires.

In addition, there are signs of a desire to show the world what has been achieved in terms of self-awareness. The participants spontaneously organize themselves to create informative videos about their disease, circle dance projects, and volunteering experiences.

I serenely realize that I have arrived at the end of a journey. The participants seem pacified in their relationship with their disease, having identified strategies to contain their symptoms and having come to terms with the idea of a chronic course, impossible to predict and always under control. Their moods seem serene and sustained, as do their bodies, which convey great presence, centrality, connection between the parts, and the ability to draw on different styles of movement.

As a therapist, I feel a strong sense of gratitude toward the patients who have chosen to embark on such an intimate journey with me. Bearing witness to their process has been a profound and moving experience that continues to resonate with me.

On a personal level, I continue to question the relationship between the perception of chronic pain and the possibility of reducing its impact on daily life through self-definition—regaining the right to speak for and about oneself, opposing a personal vision of the self to a two-dimensional and exclusively medicalized version and thus reclaiming one’s complexity and constructing a creative and integrated personal narrative of one’s own history.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

About the Author

Iolanda Di Bonaventura (L’Aquila, 1993) is an Italian dance/movement therapist and transmedia artist currently living in Canada. Her research is aimed at exploring human identity through artistic expression and art therapy and dance/movement therapy resources.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: iolandahdb@gmail.com; Tel.: +1-514-559-1743; 6500 Rue Hutchinson, Unit 500, Montréal, QC H2V 0B9, Canada.

References

Bion, W. R. (1961). Experiences in groups, and other papers. Tavistock Publications.

Di Quirico, A. (2012). Letting the body speak. Languages and clinical pathways of 1 [original: Lasciar parlare il corpo. Linguaggi e percorsi clinici della danza movimento terapia]. Magi Edizioni.

Franco, A. V. (2005). Recurrent urinary tract infections. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 19(6), 861–873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2005.08.003.

Friedrich, E. G. J. (1987). Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Journal of Reproductive Medicine, 32(2), 110–114.

Graziottin, A., Murina, F., Gambini, D., Taraborrelli, S., Gardella, B., Campo, M., & VuNet Study Group. (2020). Vulvar pain: The revealing scenario of leading comorbidities in 1183 cases. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 252, 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.05.052.

Harlow, B. L., & Stewart, E. G. (2003). A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: Have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association, 58(2), 82–88.

Hartmann, D., & Sarton, J. (2014). Chronic pelvic floor dysfunction. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 28(7), 977–990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.07.008.

Laban, R. V., & Ullmann, L. (2021). The mastery of movement, 4th ed. Dance Books.

Loman, S., & Merman, H. (1996). The KMP: A tool for dance/movement therapy. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 18(1), 29–51.

Mathias, S. D., Kuppermann, M., Liberman, R. F., Lipschutz, R. C., & Steege, J. F. (1996). Chronic pelvic pain: Prevalence, health-related quality of life, and economic correlates. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 87(3), 321–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-7844(95)00458-0.

Nguyen, R. H., Turner, R. M., Rydell, S. A., Maclehose, R. F., & Harlow, B. L. (2013). Perceived stereotyping and seeking care for chronic vulvar pain. Pain Medicine, 14(10), 1461–1467. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12151.

Porges, S. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions attachment communication self-regulation. W.W. Norton.

Reed, B. D. (2006). Vulvodynia: diagnosis and management. American Family Physician, 73(7), 1231 –1238.

Schmais, C. (1998). Understanding the dance/movement therapy group. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 20, 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022845708143.

Vieira-Baptista, P., Lima-Silva, J., Pérez-López, F. R., Preti, M., & Bornstein, J. (2018). Vulvodynia: A disease commonly hidden in plain sight. Case Report in Women’s Health, 20, e00079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crwh.2018.e00079.

Yalom, I. D., & Leszcz, M. (2020). The theory and practice of group psychotherapy, 6th ed. Basic Books.

1 In DMT, the word “effort” indicates “the expression or dynamic range of movement […] referring to the way in which a person uses their kinetic energy, expressing their internal attitudes to the demands of the external environment, the flow of muscular tension, space, time and weight.” In particular, “effort flow” refers to a motor quality that forms the basis of the movement and refers to its degree of fluidity; it describes the variations in muscular tension and ranges from free (movements that are difficult to stop abruptly, in which the agonist and antagonist muscles contract alternately) to bound (controlled movements in which the agonist and antagonist muscles act simultaneously) (Di Quirico, 2012; Loman & Merman, 1996).

2 The term “high intensity” is an attribute of effort flow used to describe—in Laban Movement Analysis language—movement styles that emphasize extreme levels (very free or very bound) of tension flow. Movements characterized by bound flow at high intensity appear to be characterized by obvious tension and effort; sometimes, they take on immobilizing characteristics (where effort and tension create a sort of “protective muscular shell”) (Di Quirico, 2012; Loman & Merman, 1996).