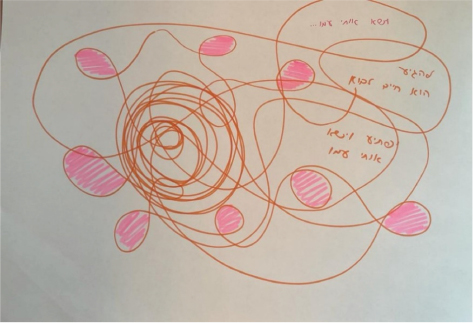

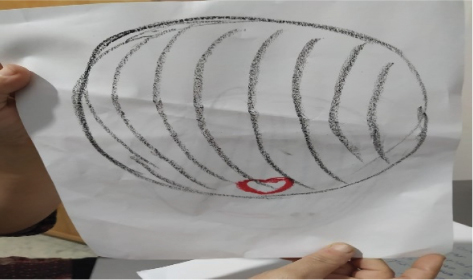

FIGURE 1 | “The Wounded Artist.”

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2023) 9(1):61–76 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2023/9/8 |

Israeli Teachers and Expressive Therapists Understanding of Selective Mutism

以色列教师和表达性治疗师对选择性缄默症的理解

Lesley University, USA

Abstract

Selective mutism (SM) is a disorder originating in anxiety in which a child between the ages of 3 and 5 years does not speak at school but speaks at home. This study used art-based research with phenomenological qualitative inquiry to understand the perspectives of professionals in the Israeli school system who work with children diagnosed with SM. The researcher facilitated a professional workshop for 13 participants to broaden their knowledge and investigate their opinions. They learned about the disorder and created artwork illustrating their feelings about working with these children. Outcomes showed that participants felt isolated and alone, and the group setting held a space for them to better understand how to work with children with SM.

Keywords: elective mutism, professional workshop, communication, teacher’s expressive art therapist

摘要

选择性缄默症(SM)是一种起源于焦虑的障碍,3-5岁的儿童在学校不说话,但在家里可以说话。这项研究使用了艺术本位研究与现象学的定性探究,以了解以色列学校系统中与被诊断为选择性缄默症的儿童工作的专业人士的观点。研究者促成了一次专业工作坊,使13名参与者拓宽知识并研究他们的想法。他们了解了这种障碍,并创作了艺术作品表明他们与这些儿童一起工作的感受。结果显示,参与者感到孤立、独自一人,而团体设置为他们提供了一个空间,使他们更好地理解如何与选择性缄默症儿童一起工作。

关键词: 选择性缄默症, 专业工作坊, 沟通, 教师表达性艺术治疗师

Introduction

Selective mutism (SM) is an ongoing failure to speak in specific social situations. In Israel and the United States, 0.03% to 1.90% of children are diagnosed with SM. Children with SM do not initiate conversations or respond when spoken to by others in specific environments. For instance, most are not observed speaking at school but speak freely at home and in other environments (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2022). According to Shipon-Blum (2007), not speaking at school can lead to withdrawal from social activities. In Israel, cognitive behavioral therapy and gradual exposure have been the most popular methods to treat children diagnosed with SM (Perednick & Elizur, 2016). In a prior study, Hanan (2023) investigated the lived experience of families of children diagnosed with SM using an art-based phenomenological research design. Results showed that using art as an intervention method with children diagnosed with SM might help these children communicate better because art is a nonverbal means of communication.

SM creates many difficulties for children but can be underdiagnosed if parents do not take their child for psychiatric evaluation. If untreated, children with SM will likely show deficiencies in academic, social, familial, and personal functioning (APA, 2022; Lang et al., 2016). Because they do not speak at school, it is hard to assess their learning. However, they often communicate by nonverbal means, such as writing. These children can act shy, be socially isolated, show negativist thinking, have temper tantrums, or display oppositional behavior, and their parents are often described as overprotective and controlling (APA, 2022). Children with SM often suffer from severe impairments at school, including harassment and bullying.

Many children outgrow SM, but the longitudinal course of the disorder is unknown. Most are not diagnosed before they start school or when they have a separate communication disorder or autism spectrum disorder. The diagnosis relies on symptoms observed for 1 month—as long as that month does not coincide with the first month of school. A diagnosis of anxiety often accompanies the SM diagnosis because SM is often comorbid with other anxiety symptoms. The differential diagnosis distinguishes between speech and language disorders because these conditions are not restricted to social situations (APA, 2022). For instance, SM differs from autism spectrum disorder in that a child with SM understands social cues. Nevertheless, there is comorbidity between SM and specific phobia, oppositional behavior, and communication delays.

In the past, SM was perceived as a deficit wherein a child actively chose not to speak. The disorder was known as “elective mutism”; the name was changed after research suggested that the child does not choose when to speak (Amir, 2005; Cohan et al., 2006; Dillon, 2016; Hung et al., 2012). Instead, anxiety causes the child to not be able to speak, even when they desire to do so (Shipon-Blum, 2007). Perednick and Elizur (2016) explained that children learn through modeling. To illustrate, if parents of children with SM sense their child’s anxiety and show avoidance, the child will react with more silence, greater resistance, and more avoidance. Perednick and Elizur emphasized the importance of those parents showing their children that they are not stressed about their child’s SM anxiety. In contrast, Hanan’s (2023) study suggested that art as a nonverbal language can improve outcomes when working with clients with SM.

Personal Background

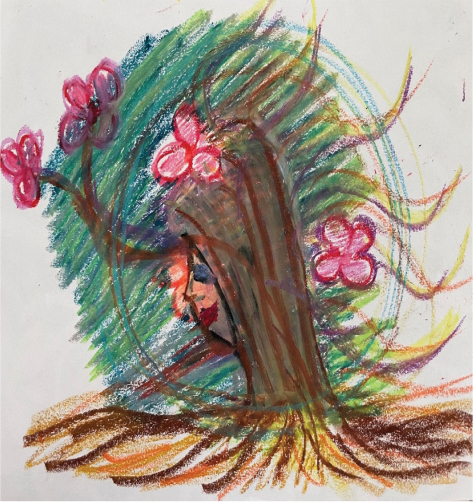

When I was a child, I had difficulty speaking out loud. In essence, I lost my voice. I remember only parts of that period. Only during the first year of my doctoral program did I remember that I did not speak as a child. My professor, Dr. Mitchell Kossak, had asked us to create the entrance to our home; I started painting a child with something covering her throat, unable to speak (Figure 1). Suddenly, long-forgotten memories from my childhood resurfaced for the first time. I zoomed into the little girl with the wounded throat, and this wound emerged. I called this painting “The Wounded Artist.” I decided to delve into a creative process and paint my emotions to reconnect to the emotions that were part of my world. The painting in Figure 2 portrays my throat as hurting because I want to speak on behalf of the little girl who could not do so. The throat is sore and hurting because it reflects the emotional difficulty that a painful experience caused. It represents my struggle.

FIGURE 1 | “The Wounded Artist.”

FIGURE 2 | “The Sore Throat.”

During this time of remembering my past, creating art was essential to reliving my emotional state when I was a little girl. It was not an easy process, but art helped revive my memories and emotions.

This research aims to help professionals and parents become more aware of the SM disorder, the unique ways of communicating within it, and methods of working with children with SM so they can begin understanding the mystery involved in the journey toward communicating.

Method

Research Design

This study combined art-based and phenomenological qualitative inquiry. Kossak (2013) defined art-based inquiry as “the use of artistic process, and the actual making of artistic expressions in all the different forms of art, as a primary mode of understanding and examining experience by therapist, client, researcher and research participants” (p. 22). According to Brinkmann and Kavale (2015), phenomenology is a method to describe and observe—rather than analyze—the data as precisely and completely as possible. This study’s methodology enabled me to understand the participants’ lived experiences. According to Moustakas (1994), phenomenology is a method of gathering knowledge of the experience by relying on “intuitive and a priori sources of knowledge and judgment” (p. 58). This method focuses directly on people’s experiences, self-evidence, and inner perceptions to understand a phenomenon.

Participants

The participants were recruited through an advertisement on Facebook inviting participation in an art-based intervention for teachers who have a child with SM in their classroom. Advertisements were also published on a WhatsApp Israeli expressive arts group and my Facebook page. Recruitment was closed after 1 week when sufficient inquiries were received to meet the study’s requirements.

The final sample of participants (see Table 1) were six teachers who had a child diagnosed with SM in their class and seven expressive art therapists (six art therapists and one drama therapist), all with teaching certificates in Israel. Participants were randomly assigned into two groups—one of six participants and the other group of seven—to keep the groups small. The uneven number resulted from the researcher’s decision to accommodate a 13th participant who was initially unsure whether they could commit to the research study but expressed significant interest and ultimately committed to it.

TABLE 1 | Participants’ Demographic Information

| Participant (pseudonym) | Age (years) | Gender | Religious affiliation | Occupation | Years of experience | Native tongue | Area in Israel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anna | 33 | Female | Orthodox | Teacher | 10.0 | Hebrew/English | South |

| Britt | 30 | Female | Secular | Teacher | 1.0 | Russian | Central |

| Claire | 45 | Female | Secular | Art therapist | 1.5 | Hebrew | Central |

| Emily | 53 | Female | Orthodox | Teacher | 31.0 | Hebrew | North |

| Irene | 48 | Female | Secular | Dance-movement therapist | 20.0 | Hebrew | North |

| Mary | 56 | Female | Secular | Art therapist | 14.0 | Hebrew | North |

| Maya | 39 | Female | Secular | Art therapist | 7.0 | Hebrew | Central |

| Madeline | 47 | Female | Secular | Art therapist | 15.0 | Hebrew | Central |

| Michele | 34 | Female | Secular | Art therapist | 7.0 | Hebrew | Central |

| Moly | 44 | Female | Orthodox | Teacher | 20.0 | Hebrew | South |

| Nina | 56 | Female | Secular | Teacher | 26.0 | Hebrew | Central |

| Oliver | 62 | Male | Orthodox | Teacher/Drama therapist | 29.0/4.0 | Hebrew | North |

Procedure

The Lesley University IRB approved this study (approval number 20/21-005), and all participants signed informed consent forms. The research consisted of a 3-hour virtual workshop comprising two 90-minute meetings and a 30-minute follow-up. As the primary researcher, I conducted all workshops. The first two meetings were held 1 week apart, and the third (follow-up) session was held 2 weeks after the second meeting. All meetings were held on Zoom due to the COVID-19 pandemic and social distancing restrictions. The Zoom software provided a unique password shared only with the participants to keep the data confidential. All the Zoom meetings were recorded. All the participants completed the entire program.

First meeting

The first meeting included an introduction of the participants, followed by a didactic presentation on the current research and theoretical knowledge about SM, such as disorder onset, prevalence, and treatment. It focused on the teachers’ knowledge of SM. I facilitated the discussion, asking participants questions like, “Can you please share with the group what you know about SM? There are no right or wrong answers. This will establish a basis of knowledge of the phenomena.”

After the discussion, I presented a case study of a young boy who was diagnosed with and treated for SM at age 15 years. It included a newspaper article I had written (Hanan, 2017). This boy had created a self-portrait using clay, wood, and plaster. During most sessions, he did not speak but expressed his feelings through art. One day, he chose to share that he feels like the old person he created with clay: “old and watching life pass.” By the end of the year, he shared that when he was 3 years old, his father had a psychotic breakdown. The boy lost his words but found them again during therapy. He then wrote a story specifying that he learned to face his fears during the creative process. This case study was sent as a link to the participants on a mutual WhatsApp group opened for the research purpose. Participants were given 15 minutes to read the article and another 10 minutes to ask clarifying questions; that ended the session.

Second meeting

The second workshop meeting had two goals: (a) to make the participants feel comfortable in making art and holding the space for them to create and (b) to facilitate an art-based intervention focused on the participants’ beliefs and opinions—specifically on the difficulties or challenges in working with children with SM. I asked, “How can you take care of a child diagnosed with SM who is in your class, and what will this entail for you emotionally?”

The first art experience allowed participants to use printer-size paper and soft oil pastels that I mailed to them in advance. Although I provided the materials, participants were not required to use them, and some preferred their own supplies. These materials were selected so participants could experiment artistically in a soft and flowing manner, using the oil pastels on paper. The participants were asked to make marks or symbols on paper as they considered their client or student or the child from the case study presented in the first meeting.

Participants then uploaded their art creations onto the group chat via Zoom software. I saved the artwork on my computer for later use in the research study. Following this, a group discussion took place about the art experience. I asked questions such as, “What image did you create? Can you explain and elaborate?” and “How does your image connect to your experience of teaching a child diagnosed with SM?” While each participant discussed their art, I asked them to share their screen so all participants could see their art creations.

As part of the discussion, I asked the participants:

Third meeting

The third group meeting, held 2 weeks after the second meeting, was a 30-minute follow-up. During this meeting, participants viewed the group’s artistic creations in a PowerPoint presentation and then reflected on their artwork. Probing questions were asked to determine whether the participants viewed their art differently or whether an aspect of the drawing stood out more in this follow-up than in the second meeting when they created it.

In this meeting, the art-based inquiry focused on the participants’ artistic experiences from the workshop and what they learned from the experience. In the PowerPoint presentation, all images made by participants were presented, as well as my artistic reflective creations theirs had inspired. There was a final discussion about the participants’ experiences, views on the art-making, and how they perceive themselves as professionals of children diagnosed with SM.

Bias

Although I received valuable information from most participants, I had difficulty communicating with some due to technical problems with the Zoom software. This limitation may have affected the overall communication in the research. For example, participants said they feared missing important information due to Internet problems. The group could have learned from questions some participants addressed to me privately. Consulting with me outside the group setting created different knowledge levels because not all participants were exposed to the same information. I tried to confront and minimize this bias by sharing these questions and answers with the group during the workshop sessions.

Results

No research has explored SM in professional’s art creations. This study used art as an intervention method. As a nonverbal means of communication, art has unique qualities to help promote conversation (Hanan, 2023). For the first time in the literature, this article discusses those unique characteristics in the participants’ art, portraying their feelings toward working with a child diagnosed with SM.

The initial thematic analysis yielded 14 main themes: learning to communicate, building bridges, breakthroughs, challenges, negative emotions, miscommunication, communicating with children with SM, gaining perspectives, applying the learning, recurring themes in paintings, community engagement, evolving knowledge of SM after participating in the study, results of participating in the research, and resources in the field. However, this article focuses only on the three themes found in the participants’ paintings.

Recurring Themes in Painting

Impenetrable bubble

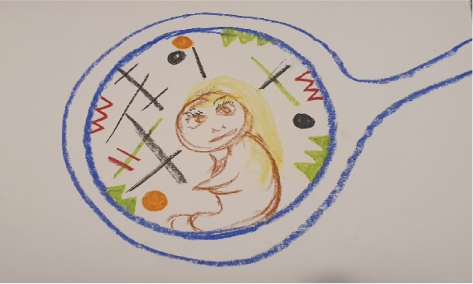

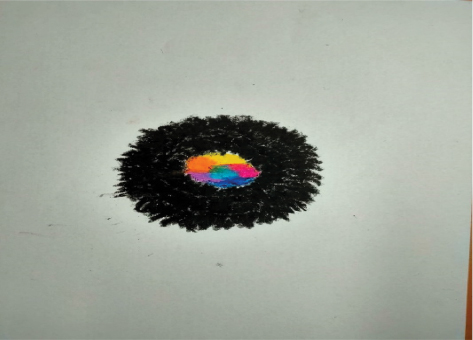

Participants drew their students or clients submerged in an impenetrable bubble without the ability to communicate with the person inside. In Figure 3, Claire painted her client submerged in an unpenetrated, see-through womb. She described how she cannot communicate with her client and feels isolated and alone. Michele made a mandala with flowers) Figure 4), and Meggie made two circles (Figure 5). The outer circle was black, representing her struggles to communicate with her client with SM; the inner circle was colorful and joyous, representing the good aspects of her relationship with her client. Madeline expressed difficulties in listening to her client, who whispers very quietly. She explained that the blue circle in the painting symbolizes that her client’s voice is prevented from being heard (Figure 6).

FIGURE 3 | Claire.

FIGURE 4 | Michele.

FIGURE 5 | Meggie.

FIGURE 6 | Madeline.

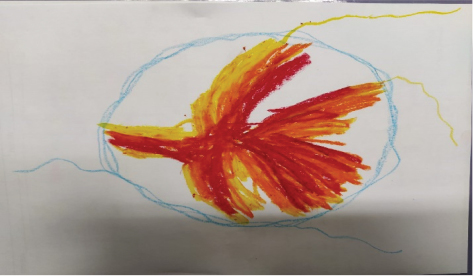

Nature imagery

Participants drew nature and flower imagery when asked to portray their clients or students with SM. Nature appeared as the primary component or appeared next to a human figure. Irene made a black flower portraying her client’s portrait (Figure 7). Britt made a predator flower next to her client’s image and explained that she feels terrified of her student’s aggressive behavior (Figure 8). Moly portrayed the first time her student spoke (Figure 9). She said that, for an entire year, she worked with her student with SM, and she felt frustrated not being able to speak with her student and made significant efforts to connect with her student but did not succeed until now. She chose to paint her student wearing her “Purim” (a Jewish holiday) costume rather than her real image.

FIGURE 7 | Irene.

FIGURE 8 | Britt.

FIGURE 9 | Moly.

Omitted body parts

When painting human figures, participants omitted body parts used for communication. Eyes, ears, mouths, and throats were missing. Nina drew only her student’s eyes, saying they were filled with anger (Figure 10). Oliver painted his client’s face, omitting the shape of the head and the entire body (Figure 11). He said he felt he had to be constantly on guard when reaching out to his client. Emily omitted the eyes, ears, and nose, drawing her student’s hair covering her face (Figure 12).

FIGURE 10 | Nina.

FIGURE 11 | Oliver.

FIGURE 12 | Emily.

Summary of Results

In the second research session, participants were asked to paint their client or student diagnosed with SM. Results showed that they tended to depict their student or client in two inner circles they referred to as an impenetrable bubble, paint nature instead of or next to a human figure, and omit body parts, especially those used for communication, when portraying body figures.

Discussion

Three themes recurred in the participants’ art creations—an impenetrable bubble, nature imagery, and omitted body parts. Participants shared that they felt frightened and apprehensive of their students’ and clients’ behaviors. The bubble image portrays a double lining comprising an internal and external circle. According to Jaroenkajornkij et al. (2022), an inner and outer circle in children’s paintings can indicate aggression and violence. Participants shared that they felt isolated and misunderstood, and some admitted they were scared of the child they were treating or did not fully understand the emotions they were experiencing.

Another motif in the participants’ art is omitted body parts. An absence of eyes and missing arms or legs can indicate helplessness and anxiety (Jaroenkajornkij et al., 2022). The participants admitted feeling helpless, isolated, and anxious when they cannot communicate with their students and clients with SM. In an earlier study, Hanan (2023) coined the term bridges to communication, meaning the need to establish straightforward, open communication with children diagnosed with SM and their parents to help the children start speaking in class or therapeutic sessions. This is done by first using art as an intervention method and then engaging in conversation. Art interventions can help decrease feelings of helplessness and isolation because art is a nonverbal means of communication.

Hanan (2023) recommends painting mandalas, choosing oil pastels and gouache, and creating a self-portrait. In this research, participants experimented with these ideas. They shared that they slowly felt less isolated and that art helped them form a bond with their clients and students. They could feel optimistic and develop empathy toward the child with SM. For instance, Meggie shared that making mandalas with her client helped them reconnect (Figure 6). Moly said that all was once black-like in the outer circle of her drawing. Now she can shift her attention to the color part of the inner circle and focus on the life and playfulness in her relationship with her student.

Results of Participating in the Research

Some participants said they felt more grounded; most wanted extended support beyond the realms of the research study. Participants in an earlier study expressed feeling more relaxed and focused when they listened to classical music. Thus, based on Hanan’s study (2023), where participants painted self-portraits while listening to Mozart’s Symphony No. 9 in C major, participants in the current study were encouraged to paint with oil pastels and play classical music with their students.

The participants were also trained to work with mandalas. Britt called this learning experience during the research “a magic intervention.” This intervention was introduced because mandalas have been shown to reduce anxiety (Curry & Kasser, 2011), and one goal of working with children with SM is to reduce anxiety levels to promote communication. Thus, mandalas were taught in the professional workshop and based on previous research (Hanan, 2023; Shipon-Blum, 2007).

Participants also commonly expressed feeling more comfortable with their voices through the research process. They learned to embrace positive changes in their self-esteem and gained new perspectives on SM. These findings match Harwood and Bork’s (2011) findings, which specified the importance of professional workshops to increase scholars’ knowledge about SM. Therefore, it is vital to educate and train professionals in the school system and students still in graduate school on how to work with children diagnosed with SM.

In addition, participants in this research study shared that the three workshops were meaningful and significantly affected their confidence when working with SM. They specified that they would have liked more sessions but that these three were impactful because participants learned what is most influential and important when working with SM. Specifically, they learned to work in ways that can reduce anxiety because research has shown that SM is an anxiety-based disorder (APA, 2022; Kaimal & Ray, 2016). Interventions (e.g., mandalas, relaxing music) can lower anxiety levels. It also stressed that participants should focus on building their students’ self-esteem while establishing a social environment that can meet the child’s needs and, most importantly, help the child with SM communicate.

Resources in the Field

This study’s participants shared the need for growing knowledge in the field, especially in educating parents about SM. They wish to continue teaching other professionals and to receive supervision from a professional who knows how to work with children with SM, has a background in expressive arts therapy, and can provide working methods for SM. Teacher participants said that until they participated in this research, they had not known anybody from the expressive arts field who knew how to work with children diagnosed with SM. There is a growing need for supervision for teachers and other professionals to obtain success in working with children diagnosed with SM.

Contribution to the Field of Expressive Arts

When working with children with SM, one often can feel speechless. Art aided me in diving deeper into the participants’ and their students’ and clients’ shared experiences and shed light where there was darkness. Figure 13 shows an art creation I made. It symbolizes the process I went through as a researcher and a leader in my community. Art can help students overcome anxiety related to SM; it is a unique tool for working with SM. Art therapists are thus uniquely capable of facilitating workshops and supporting teachers and parents. It is imperative that art therapists be at the forefront of helping to understand and treat SM.

FIGURE 13 | Researcher’s response to participants’ artwork.

Limitations

In addition to technical problems with the Zoom software addressed in the Method’s Bias section, which may have affected the overall communication in the research, my enthusiasm for treating SM may have introduced bias in the research study. I can be passionate when discussing the phenomena and perhaps cause the participants to be overly optimistic. This bias might have been better addressed if I had employed a neutral cofacilitator, who might have provided a more objective perspective. This should be considered for future research. Moreover, this research was conducted in Israel. Israel’s culture can be informal in its norms, and communication is often straightforward, open, and direct (Lautmen, 2018). In other cultures where communication norms are more ambiguous and indirect, results of a similar study may differ from these.

Recommendations for Future Research

It is crucial that research in this field continue and explore this phenomenon’s subsets. More research is needed on how art therapy can supply children diagnosed with SM with the ability to increase their self-esteem by exploring nonverbal aspects of their being and finding words to describe how they feel.

Future research is needed to explore the common misconceptions of SM to provide a more guided, precisely developed workshop. It would also be interesting to examine other aspects revealed in this study, such as omitted body parts in drawings by children with SM, professional support systems, and special features seen in the participants’ drawings, such as the flower imagery and the bubble motif. It would also be interesting to explore them to determine whether they are also seen in the art of children diagnosed with SM.

Further research is needed to establish the nature of the relationship between trauma and SM and understand whether traumatic events could cause children diagnosed with SM to show typical SM behaviors. This insight could help professionals understand the body mechanisms involved in trauma that are also connected with SM and provide additional intervention avenues. In addition, more research is needed on the disorder’s etiology, causes, and medical aspects so additional interventions can be developed. Finally, longer workshops that help professionals reconnect with their own emotions, including fears, and implementing art as a way to research their own felt experiences in working with children diagnosed with SM might be useful.

Conclusion

The myriad sensations that arose during this research for the participants and me were interesting. As one participant said about taking part in this research experience, “We won the jackpot.” They also asked to continue learning from my knowledge and were reluctant for the study to end. The participants shared two important aspects of the emotional experience: how isolated they felt and the responsibility they chose to take on when working with children diagnosed with SM in the Israeli education system. It is essential to educate professionals on the existing literature and assure them that they are not alone. Being part of a group was one factor that helped participants feel more validated and affirmed during the research. Notably, the workshops helped professionals work with children with SM. Because workshops are designed to be short-term and inexpensive to conduct, they can easily be implemented in schools across Israel and provided to professionals worldwide.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declares no conflict of interest.

About the Author

Tal Hanan has worked as a certified Israeli art therapist since 2010. She received her BSC from Beit-Berl College, her MA. from Tel Aviv University, and her PhD from Lesley University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Using art and music in her private practice in Herzeliya, Israel, Tal works with children ages 3 to 7 years old diagnosed with selective mutism and language disabilities. Tal focuses her work on helping those who are unable to speak due to anxiety disorders, stress, or developmental deficits. She believes art can be a nonverbal vehicle to help children reconnect to their emotions. Through this process, children recover their voices.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed: E-Mail: thetal23@gmail.com

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed., text rev. APA. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787.

Amir, D. (2005). Re-finding the voice: Music therapy with a girl who has selective mutism. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 14(1), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.11080/08098130509478127.

Brinkmann, S., & Kavale, S. (2015). IntreViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Sage.

Cohan, S. L., Chavira, D. A., & Stein, M. B., (2006). Psychosocial interventions for children with selective mutism: A critical evaluation of the literature from 1990–2005. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(11), 1085–1097. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01662x.

Curry, N., & Kasser, T., (2011). Can coloring mandalas reduce anxiety? Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 22(2), 81–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2005.10129441.

Dillon, J. R. (2016). An examination of school professionals’ knowledge of selective mutism (Publication No. 10139827). Doctoral dissertation, St. John’s University, New York. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Hanan, T. (2017, December 17). Ceitzad Peula Yetziratit Yechola Litrom Leripui Veim Cedai Lishtok Bemeala’ca? [How does creativity help promote health and should one be silent in artmaking?]. A’aretzh. Advance online publication. כיצד פעולה יצירתית יכולה לתרום לריפוי, והאם כדאי לשתוק במהלכה? - אמנות מקדמת בריאות - הארץ (haaretz.co.il).

Hanan, T. (2023). Israeli professionals understanding of selective mutism. Doctoral dissertation, Lesley University. Lesley University Digital Commons. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_dissertations/120/.

Harwood, D., & Bork, P.-L. (2011). Meeting educators where they are: Professional development to address selective mutism. Canadian Journal of Education, 34(3), 136–152.

Hung, S. H., Spencer, M. S., & Dronanmraju, R. (2012). Selective mutism: Practice and intervention strategies for children. Children & Schools Advance Access, 34(4), 222–230. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cds006.

Jaroenkajornkij, N., Lev-Wiesel, R., & Binson, B. (2022). Use of self-figure drawing as an assessment tool for child abuse: Differentiating between sexual, physical, and emotional abuse. Children, 9(6), 868. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060868.

Kaimal, G., & Ray, K. (2016). Free art-making in an art therapy open studio: Changes in affect and self-efficacy. Arts & Health, 9(2), 154–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2016.1217248.

Kossak, M. (2013). Art-based inquiry: It is what we do! In S. McNiff (Ed.), Art as research (pp. 19–27). Intellect.

Lang, C., Nir, Z., Gothelf, A., Domachevsky, S., Ginton, L., Kushnir, J., & Gothelf, D. (2016). The outcome of children with selective mutism following cognitive behavioral intervention: A follow up study. European Journal of Pediatric, 175, 481–487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-015-2651-0.

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Sage.

Perednick, R., & Elizur Y. (2016). Ilmut selektivit madrich leorim morim [Selective mutism: A guide for parents teachers and therapists]. Achbooks.

Shipon-Blum, E. (2007). The ideal classroom setting for the selectively mute child. SMART-Center.