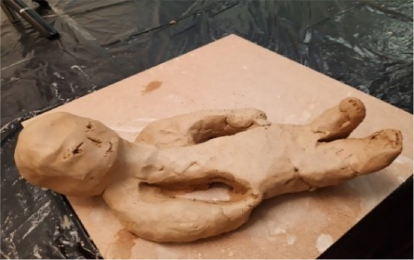

FIGURE 1 | Assaf’s artwork Coming to the World, clay on plywood (6 × 14 × 33 cm).

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2023) 9(1):45–60 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2023/9/5 |

Molding the Fear: Representations of Fatherhood in Clay by Violent Men

形塑恐惧: 暴力男性粘土创作中的父性象征

Ono Academy, Israel

Abstract

This article presents an artistic inquiry among three students during an art-based research course in the art therapy master’s program at Ono Academy, Israel. Their collaboration focused on composing inquiry modes that could explore paternal representations of violent men that arise in artmaking with clay. Three fathers who took part in an abuse-prevention art therapy group, their group facilitator as a witness, and the three student-researchers participated in the project. The paper focuses on the research method that comprised artmaking with clay, a questionnaire, observations, and discussions. Two main themes arose within the study: coexisting contrasts and false perfection as well as a gained sense of success and assurance that could project onto their perceptions of parenting. The project highlights the significance of artmaking with clay as a research tool and as a potential prophylactic treatment for preventing domestic violence.

Keywords: fatherhood, domestic violence, clay in research, art-based research, paternity

摘要

本文介绍了三名学生在以色列奥诺学院(Ono Academy)艺术治疗硕士项目艺术本位研究课程期间进行的艺术探究。他们的合作重点是组成探究模型,能探索出现于粘土艺术创作中暴力男性的父性象征。参加预防虐待艺术治疗小组的三位父亲、作为见证者的团体促进者人以及三位学生研究员参与了该项目。本文聚焦于由粘土艺术创作、一项问卷调查、观察和讨论组成的研究方法。研究中出现了两个主要主题:共存的对比和虚假的完美,以及能投射他们养育观念的成功感和自信。该项目强调了粘土艺术创作作为一种研究工具和预防家庭暴力的潜在预防疗法的重要性。

关键词: 父性, 家庭暴力, 用于研究的粘土, 艺术本位研究, 父亲身份

Introduction

This article focuses on paternal characteristics of violent men, as manifested in an art-based pilot study using creative processes and artmaking with clay.

Four fathers defined as violent men participated in the study. These men took part in a violence-prevention group therapy facilitated by an experienced art therapist, for several months prior to the pilot research project. The researchers in the study were three students in their second year of art therapy, who collaborated with their professor of an art-based research course at the Ono Academy in Israel. The three students encountered domestic violence during different stages in their lives and aspired to deepen their understanding of how this population perceives fatherhood. They believed that creative endeavors and symbolic language could facilitate the expression of violent men, who are yearning for empathy and acceptance within therapeutic space (Ben Porat et al., 2018). The research method was art-based and included several inquiry modes: an experiential meeting with the participating-fathers, a questionnaire, artmaking with clay, phenomenological observation of the creative processes and products, discussions, and response artmaking by the researchers.

The study process exhibited two main themes: coexisting contrasts and false perfection, suggesting that creative processes with clay, given its regressive nature, allow participants to hold contrasts and to discover their perception of parental relationship with their own fathers. The study provides a glimpse into artistic processes as significant research instruments and their dominance in facilitating authentic expression within oppressed populations.

Literature Review

Paternity

Research into the role of fatherhood began in the 1970s due to changes in the labor market and social norms for women (Bat-Or & Greinmann-Bauch, 2017; Carmel, 2019). According to Alser (2011), little importance was directed to paternity in professional literature. In the book Raising Cain: Protecting the Emotional Life of Boys (2009), Dan Kindlon and Michael Thompson write about their experience in treating families and finding angry, frustrated, and silent boys, who were brought up to suppress compassion, sensitivity, and warmth. The family psychotherapist Noam Israeli (2020) strengthens this claim by tying together the dominant image of masculinity that requires strength, to acts of cruelty—expressed by verbal and emotional brutality—that could lead to aggression and abuse. As opposed to these aggressive contents, positive aspects of paternity are known to promote a healthy separation process, build gender identity, and form an essential model in education values (Alser, 2011).

Erikson (1950) mentions faith as a trait that develops in the first stage of life, significant for the differentiation process. According to Weir (1995) and Bowlby (2005), difficulties in developing self-confidence during the process of differentiation could create a false sense of omnipotence and the need to preserve control (Dalley et al, 2013). In describing the narcissistic disorder, Cohen (2016) refers to desire, abandonment anxiety, and a need for control and security. These states of mind express longing for unrealistic situations, rigidity, and irrational thinking (Dotan, 2016; Reel, 1999).

Violent Paternity

The OECD conference in 2020 for the eradication of domestic violence, stated that “domestic violence is not an event that exists in certain households, but it is anchored within a society that allows it to occur” and claimed that domestic violence is occasionally associated with non-verbal, cultural and gender-oriented messages (OECD, 2020, p. 21). The conference addressed the fact that experiences and exposure to violence during childhood and the use of violence during adolescence are closely related.

In recent years, the focus on treating violent men has increased. Men who have completed therapeutic processes were less likely to behave violently than men who have dropped out of therapy. This is due to the established connection to parts of the self, such as vulnerability, sadness, pain, helplessness, and compassion (Ben Porat et al., 2018).

Contrasts

According to Gurvitz and Arab (2012), dialectics is a methodology that originates from Greek philosophy in which the tension between contradictory claims leads to truth and completeness. Rudolf Arnheim (2004) claims that movement between contrasts enables progress and develops a position that accepts ambivalence as part of existence. The psychodynamic point of view proposes that conflicting emotions and drives aspire to express themselves, and a balance between them constitutes a central element in proper development (Gil, 2018; Lance, 2011; Yalom, 2002). From an artistic perspective, Carmel (2019) and Lev (2020) suggest that creativity is the ability to unite contrasts in favor of new ideas.

Contrasting Qualities in Clay

Clay is a natural material made from soil, commonly used in art therapy (Orbach, 2017). Clay is flexible, and its molding promotes unity with nature, and with polarized emotions such as playfulness, anxiety, serenity, aggression, joy, and such (Nan et al., 2021; Richards, 2011). Clay, as a primary material, carries qualities that encourage regression (Govoni et al., 2022). Sholt and Gavron (2006) assert that the therapeutic aspects of clay lie in merging physical and mental processes. This constitutes a window to unconscious content, especially for people who struggle to express themselves verbally, bypassing defense mechanisms.

Clay in Art-based Research

Clay has several unique characteristics that make it an effective research tool in art-based research. Its tactile and malleable nature allows individuals to physically engage with the medium, shaping and molding it to their liking, which can facilitate a deeper connection to the material and a greater expression of emotions and experiences (Bat-Or, 2010; Duckrow Fonda, 2017). Recent research studies have shown that clay can be used to explore a wide range of topics, from trauma and identity to social justice issues (Agyei et al., 2021). For example, a study by Skop et al. (2022) demonstrated how using clay in art-based therapy sessions with survivors of domestic violence helped facilitate the expression of emotions and experiences that were difficult to verbalize. Beauregard et al. (2020) highlighted the earthy nature of clay that in a group setting can foster a sense of community and belonging, providing individuals with an opportunity to connect with others and share their experiences. These studies highlight the potential for generating new insights with clay in research.

The existing research on the use of clay in art-based research with violent men is limited, and there is a need to explore the potential of this medium further. This study aims to narrow this gap in the literature by using clay to explore parental perceptions of violent men and their roles as parents.

Methodology

One of the requirements for students in the art-based research course was composing a methodology most suitable for their research topic under academic ethical regulations. Working in couples or triads students were encouraged to find a research topic with a shared interest. For students, unfamiliar with one another, and inexperienced with such a paradigm, it was an [almost] impossible mission.

An art-based method was adapted to the unique population in this pilot study, allowing exploration of fatherhood among men known to be violent. The use of creative tools and processes promoted understanding and awareness of the parenting characteristics to which the participants were exposed at a young age. The research method emphasized art, both as an emotional language and as a healing factor that invites change.

Participants and Setting

Four fathers between the ages of 29 and 46 years, recognized as violent men, who vary in their sociocultural backgrounds participated in the research. These men voluntarily took part in weekly meetings in a therapeutic group at a Prevention of Domestic Violence Center in Israel, for approximately eight months and, hence, knew one another. Despite signing a consent form, one man did not complete the research process. The group facilitator—an experienced art therapist—participated as a witness during the experiential meeting, in the hope to promote safety and alleviate the participating-fathers’ anxiety. The three students participated as active researchers. For the purpose of anonymity, the following pseudo-names were used for the fathers: Yaron, Roy, and Assaf. The three researchers will be presented by their real names: Israella, Daniella, and Renana.

Recruiting the fathers was challenging. The researchers first contacted social services officials in the Israeli Ministry of Welfare, which is responsible for the prevention of domestic violence. However, the formal approval process was complex and did not meet the course time limit. Then, they published a call for participation on social media, yet these attempts were futile. Advised by their professor, they contacted her colleague—an experienced art therapist working with groups of violent men—and requested her assistance in granting permission and IRB approval for the research project. The approval was granted for a group facilitated by her, provided she is present as a witness during the experiential meeting with the men.

The study took place in February 2020, amidst the Covid-19 pandemic. It included a single 90-minute experiential meeting with the fathers, at the Domestic Violence Prevention Center in southern Israel. The meeting was held in the same room where the group meets weekly, leaving the doors open at the request of the fathers. To comply with the health restrictions of the pandemic, all participants wore facial masks and maintained social distancing in order to prevent infection.

Research Process

Four inquiry modes were used to explore paternal representations of violent men: an experiential meeting with all participants that included filling out a questionnaire, artmaking with clay, phenomenological observation, and a discussion relating to the creative processes and products. Three fathers arrived at the scheduled time and began filling out the questionnaires. When the last man arrived, he sat down beside the group facilitator he knew, reviewed the forms while listening to the warm-up directive, watched the other fathers working with clay and then left. All attempts to persuade him to stay with his fellow male-participants failed. Once questionnaires were filled-out, the three fathers chose a personal workspace that included a 25 × 25-cm plywood board with a 15 × 15-cm lump of clay on it, five wooden working tools, a water bowl, and paper towels. A video camera was placed next to each participant, directed at his hands to preserve anonymity.

Artmaking with Clay

As a warm-up, the researchers explained the nature of clay and its qualities. They invited the fathers to touch the clay and pay attention to their feelings that arise. Then, the fathers were asked to create an image representing their relationship with their children. Each researcher accompanied one father throughout the meeting, documenting the creative process in an observation log. The researchers originally planned to devote 40 minutes to artmaking and 30 minutes to a group reflective discussion. Subsequently, the creative processes of the fathers were not in-synch, which required their flexibility. Thus, discussions were conducted with each father individually.

Creative Observation and Discussions

Immediately after artmaking, a discussion was held with each father that began with an invitation to observe the clay artwork from all sides and reply to the question—“What do you see?” (Betensky, 1977). Then, the fathers were asked to describe their creative process in detail. The researchers inquired whether they experienced frustration or difficulty during sculpting, striving to broaden an understanding of the parenthood to which the fathers were exposed as children. Therefore, they asked: “If you could mold the clay to symbolize your relationship with your father, can you describe what it would look like?”

Creative Responding by the Researchers

In art-based research, the artistic expressions of the researchers are used as investigation tools, offering additional ways of understanding, and communicating human experiences (Kossak, 2021; McNiff, 2018). Therefore, after the fathers left, the researchers remained in the room and responded artistically to the previous inquiry modes, by using similar lumps of clay (15 × 15 cm). They documented their creative processes and products with photos and observation logs.

Systematic Analysis of the Research Information

The research tools included questionnaires for gathering personal information from the fathers, researchers’ observation logs, footage of participants’ hand movements, the participants’ created artworks, photographs, audio recordings of the experiential meeting, and transcribed discussions.

The systematic analysis included listening to the audio recordings, transcribing them, watching, and analyzing the footage, with and without sound. The researchers referred to the work structure, hand movements, and artmaking techniques. They observed and examined the artworks according to the phenomenological-aesthetic approach that traces the nature of the phenomena (Betensky, 1977). They also drew on their observation logs to recall feelings and interpretations stemming from the experiential meeting and the process as a whole (Lev, 2022). Then, they discussed the body of information, distilling the main themes that could answer the research question. A significant objective of the research course is to instill a thorough, systematic, analysis process. This was encouraged by inviting the students to present their research methods and findings to their classmates, engaging the class in brainstorming, asking questions, and providing relevant feedback. This process helped the researchers solidify their findings and deliberate with their course professor who referred them to relevant literature from psychology, sociology, philosophy, and art therapy.

Findings

Two main ideas emerged in seeking to find representations of fatherhood by violent men: coexisting contrasts and false perfection. These findings were salient among all research stages and inquiry modes.

Coexisting Contrasts

Upon hearing about the research proposal and reading about the research process outline, some of the fathers expressed their concerns for religious reasons. Shortly into the meeting, they seemed relaxed, providing their full cooperation. The researchers also felt intense, conflicting emotions. They were reluctant about meeting violent men; they were intimidated to approach them and to be close with them, however, once the fathers engaged with artmaking their fear made way for feeling compassion, excitement, and empathy towards them.

Contrasting Touch

While examining the footage of participants’ artmaking with clay, the researchers noted contrasts in manners of touch. These included gentle and soft touching versus tough and aggressive ones. For example, participant Assaf caressed his artwork Coming to the World at length during the creative process while focusing on its intentional injury (Figure 1). He said: “A baby is born wounded…unclean.” Participant Yaron molded the clay gently, and then submerged into pressing and crushing the clay with both hands—movements that reflected violence and great strength. All the fathers engraved the clay in their creative processes, which made the researchers feel uncomfortable while witnessing them during the meeting and when watching the footage.

FIGURE 1 | Assaf’s artwork Coming to the World, clay on plywood (6 × 14 × 33 cm).

Contradictions in Demeanor

The fathers agreed to become exposed through the creative process and verbal discussions. They expressed in detail aspects of their fatherhood they were not proud of. However, they chose to remain silent when asked about their own childhood. Assaf, who began creating before the video cameras were turned on, tried to hide parts of his process afterwards, and Roy chose to conceal his artwork.

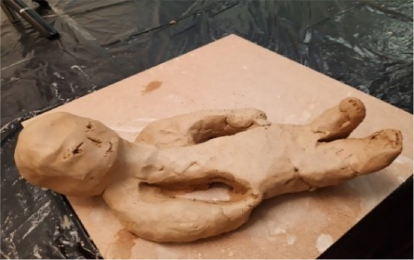

Contradictions were also expressed verbally by the fathers. For example, Assaf compared the qualities of the clay to his own, unrealistically: “It’s a strong material…both strong and flexible…it varies.” Then he said, “I am a very emotional person, [I know] I don’t seem so but…” Yaron, spoke highly of his children’s future, and related to the tree he created, “What future do I wish for my children? Strength and growth,” when in fact, Yaron has four indictments for severe violence.

Contrasting Perceptions

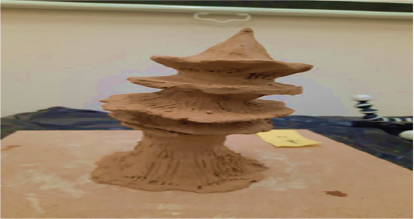

The researchers evidenced contrasts between the fathers’ projected perceptions of their artworks. According to Yaron, his artwork The Levinsky Tree was strong and stable as a metaphor for his children, however, the artwork tilted sideways affecting its steadiness (Figure 2). Roy created his human figures fragile and weak while making other objects robust (Figure 3). Assaf bonded the organs of his artwork tightly using water, yet the figure’s head exceeded the limits of the platform placing it at risk (Figure 1).

FIGURE 2 | Yaron’s artwork The Levinsky Tree, clay on plywood (10 × 12 × 20 cm).

FIGURE 3 | Roy’s artwork Quality Time, clay on plywood (5 × 10 × 17 cm).

The table in the responding artwork of researcher Israella, Table and Child (Figure 4), serves as a playful hiding place for children but also offers a sheltering space for the threatened child. Researcher Renana, referred to her artwork hand (Figure 5), as open, giving, reaching out, and touching, however, its texture is rough and coarse. Researcher Daniella’s artwork needle and thread (Figure 6), represents the potential for both stabbing and repair.

FIGURE 4 | Researcher Israella, response-art. Table and Child, clay on plywood (10 × 9 × 9 cm).

FIGURE 5 | Researcher Renana, response art. Hand, clay on plywood (6 × 10 × 15 cm).

FIGURE 6 | Researcher Daniella, response-art. Needle and Thread, clay on plywood (2 × 35 × 37 cm).

The researchers acknowledged coexisting contrasts in their response artworks; their desire for reparation and connection vis-à-vis pain and roughness. They understood that their ability to hold contrasts points to development and growth. The fathers have taken part in sessions of group art therapy prior to the research that did not involve working with clay. It is possible that the qualities of clay facilitated their creative expression, enabling contrasts to coexist. In this manner, the advantage of art therapy grows in providing the space for violent men to experience regression and become contend with ambivalent attachment experiences and anxieties.

False Perfection

Pretense perfection was seen in participants’ created imagery as “fantastic Kodak moments.” Assaf described the baby in his artwork Coming into the World as the perfect baby at birth. Yaron’s Levinsky Tree, which symbolizes his family, presented an opulent tree decorated with an engraving and a heart. Roy’s artwork Quality Time showed a father and his children under the covers in bed watching television. He described his artwork as capturing the happiest moment in his life. Israella’s response art Table and Child presents a table with massive legs and a rather thin platform for its top (Figure 4). She wrote in her observation log: “It seems as if these heavy legs desire to compensate for the fear of the child seated underneath [the table].”

While watching and analyzing participants’ creative processes, the researchers noted much time and effort that were invested in stabilizing and perfecting the artworks. Assaf’s footage revealed his tightening, squeezing and caressing of the baby´s figure as well as using a large amount of clay to make it stronger. During the discussions, especially when asked about their parental frustrations, the fathers highlighted deficiencies, leading to compensations.

Enmeshment in False Perfection

Enmeshment was noted in participants’ artworks and creative processes. Assaf, for example, created a lumpy baby figure with arms as a part of its body (Figure 1). During the discussion with Assaf, he first referred to the figure as his firstborn daughter, then he said the image could symbolize him “I may have put something of myself into the whole thing,” “I put the baby within me into this baby,” and added, “we are all babies.” The baby he created became “all babies.” At the end of the meeting, Assaf struggled to separate from his creation.

In Roy’s artwork, there is no space between the two children and their father in bed (Figure 3). Roy was not satisfied with the physical proximity of the kids to the father in bed, and added: “I am attached to them, and they are attached to me.” Yaron’s artwork was a chunk of clay as a tree trunk with no branches (Figure 2). He explained that his on-block artwork represents a family unit, although he was asked to create a relationship. In the discussion, he described the image as the family tree and then engraved the tree with a nickname to imprint it.

A lack of separation was seen in the researchers’ response artworks. Daniella made changes in her first response art Needle and Thread. She folded the needle, rolled the thread into a ball and placed it in the eye of the needle unifying them. Observing the artwork in its final stage she said it looked like a symbiotic primary relationship, and renamed it Ball and Needle (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7 | Researcher Daniella, response-art. Ball and Needle, clay on plywood (13 × 9 × 18 cm).

Participants seemed to mistake enmeshment for closeness, when in fact, it led to indistinction. While listening to the audio recordings of the experiential meeting and the discussions, the researchers struggled with hearing the conversations clearly. During the meeting, the fathers requested to leave the doors open. The volume of the traffic coming from the street was equally loud as the participants’ voices, which made it very difficult to distinguish between them.

Discussion

Within art-based methodology, artistic expressions serve the researchers and participants for comprehension and assessment (Kossak, 2021; McNiff, 2014). The created artworks represent contents and meanings, emphasizing their significance (Lev, 2021; 2022; Duckrow Fonda, 2017). This research echoed other researchers who found the transition between working with clay to the verbal discussions, facilitates expression (Agyei et al., 2021; Govoni et al., 2022) and exposure and transformation of paternal perceptions (Bat-Or, 2010; Bat-Or & Greinmann-Bauch, 2017).

Contemporary literature and research provide a broader view of paternity than in the past (Israeli, 2020). Until the 1970s, fathers were seen primarily as punishing and oppressive figures, having less influence on the child’s development than mothers. Over time, the need to understand paternity arose (Alser, 2011; Carmel, 2019; Kindlon & Thompson, 2009). Findings in this pilot contradict these perceptions and suggest an existing inter-generation influence of fathers’ behaviors on their children. Such influences, when processed through artmaking with clay revealed coexisting contrasts, and false perfection.

In the OECD conference held in 2020 to eradicate acts of domestic violence, it was emphasized that violence in adulthood is related to exposure to violence in childhood, and to cultural non-verbal messages (p. 21). This is significant in understanding violence as part of post-trauma (Cohen 2016; OECD 2020; Sofer, 2009; Yassur-Borochowitz, 2003). The behaviors of many violent men are related to their traumatic past, which affects the development of both personality and identity, coping and regulation mechanisms, differing between good and evil, and their attachment styles (Bancroft, 2014; Sofer, 2007). The fathers in this study were all exposed to violence in their childhood. When asked about the similarities between their created imagery and their childhood memories, Roy whispered, “It’s not similar at all…these are not things that I’ve experienced.” Roy’s reaction demonstrated coexisting contrasts in his perception of self.

Given that the fathers in this research had adult children, it could be assumed that they acknowledge their imperfect parenthood. However, the findings support claims referring to the parenthood styles of violent men as inseparable from other violent behaviors and their perceptions as a whole (Bat-Or & Grenimann-Bauch, 2017; Carmel, 2019). In Bowlby’s attachment theory, pathology is related to an avoidant, ambivalent, and anxious style (2005). Sofer (2009) added that extroverted and violent behaviors lay on these attachment styles and also relate to emotional dependence and frustration from separation. This research echoes these perceptions in seeing the fathers’ difficulty in promoting independence in their children.

A lack of differentiation in parenthood styles may distress fathers who perceive their children developing or enjoying a relationship with another significant person (Cohen, 2016; Dotan, 2016). In this study, Assaf created a figure whose hands were attached to its body and explained: “I preferred to use the whole and not break it down into parts…I didn’t see…a need.” He also describes a lack of development: “This memory regenerates…this will always be my attitude towards my childhood.” Roy created an artwork of three children and their father in bed under a heavy blanket and said: “They were fighting who is closer to me…[I] am attached to them and they are attached to me.” Sofer (2009) claims that a traumatic experience in the family is detrimental to the attachment for the unmanaged stress in the parent-child relationship. It can be assumed that parenting styles that do not encourage separation, could recreate the father’s experience as a child and lead to enmeshment.

False perfection arose in all participants in the study. The researchers took extra precautions to make sure the fathers cooperate with disclosing their emotions and agree to work with clay. Their shared, valid concerns were compensated for by excessive preparations of the meeting room, their conversations with the group art therapist, and the security they drew from her presence as a witness. Contemporary literature recognizes dominant characteristics of violent men as the need to control others, and aggressive self-defense against any threat to internal boundaries (Cohen, 2004). During the discussion, Yaron said, “It was uncomfortable for me to create. The table was too low, and I needed much more material.” Furthermore, the literature suggests that their choice in violent behavior stems from the need to confirm one’s self-worth in others (Kindlon & Thompson, 2009; Israeli, 2020; Ben Porat et al., 2018). In this research, Roy said, “If I had more time, I would have made it nicer…all of it…I like to pay attention to the small details in sculpting…I strive for perfection.” Assaf too, spoke about his artwork: “This goes to the museum later…I captured it as one of the happiest moments in my life, maybe the happiest ever!” These examples reflect false perceptions of self that were also apparent when the fathers struggled to accept their flaws in parenthood, in self, and in their children, expressing their constant frustration.

The researchers’ concerns before meeting the fathers also stemmed from their artistic familiarity with clay, as a material that invites regressive expression (Beauregard et al., 2020; Richards, 2011). They worried about the possible implications in response to feelings of frustration that might arise towards the clay and affect the fathers’ behavior. The men’s dedication to the process was surprising. The pilot’s findings highlight Carmel’s opinion about the power of artmaking for maintaining contrasts (Carmel, 2019; Skop et al., 2022). This idea was manifested in all the inquiry modes of this research project. During the creative processes, the researchers noted soft and gentle strokes of the clay alongside aggressive slapping and scratching. The discussions with the fathers ignited their constant movement from being open to concealing, and during the systematic analysis, the researchers circled between unanimous agreement to dispute, and between feeling close and understood to being detached and alienated. These conditions reverberate Lev (2020) in suggesting art as a mediator between contradictions.

A report submitted to the Ministry of Labor and Welfare in Israel found low motivation for therapy in violent men and a dropout rate of 28%–90% during such interventions (Ben Porat et al., 2018). Nevertheless, those who complete therapeutic processes are likely to reduce their violent behavior. According to Ben Porat et al. (2018), such men reported developing an ability to connect to self-parts, such as vulnerability, sadness, pain, helplessness, and compassion. The fathers in the study are violent men who have participated in group art therapy for eight months. Despite the common focus of research on pathologies within violent men, this research illuminated other aspects of this population that were by using tools and materials that promote expression under safe, therapeutic conditions.

It is known that art enables the expression of emotions that cannot be manifested in words and that creative processes with art materials invite meaningful connections between the conscious and the unconscious (Duckrow Fonda, 2017; Lev et al., 2021). Working with clay as a natural, earth-like material could lead to unveiling primal content that is reminiscent of early sensations (Agyei et al., 2021; Beauregard et al., 2020; Skop et al., 2022). Within art therapy, clay is used to bring up unconscious content as a window to the soul, bypassing defense mechanisms (Govoni et al., 2022). In this research, tinkering with clay led participants to experience competence and success in dealing with frustration and revealing childhood injuries. It, therefore, suggests that continued work with clay could instigate means for coping with feeling helpless and resentful, which hopefully could diminish the need to control others.

Conclusion

This pilot study sought to examine paternal representations that arise in artmaking with clay, among fathers recognized as violent men. It demonstrates the process of conducting an art-based exploration by three students of art therapy, who had encountered domestic violence during their lives. The study method comprised several inquiry modes: creative processes with clay, completing a questionnaire, observation and discussions, and response art.

Systematic analysis and artmaking were used to process the research material that included video footage of the experiential meeting, artworks, audio recordings of the discussions, questionnaires, and observation logs. In answering the research question, two main ideas were salient throughout the inquiry modes: coexisting contrasts, and false perfection.

Contrasting feelings of repulsion, apprehension, empathy, and compassion arose in the researchers during the experiential meeting with participants. While processing the research information, the footage revealed contrasts in the demeanor and perception of the fathers through artmaking and during the discussions. The pilot highlighted art as a mediator (Lev, 2020) between these contrasts. False perfection was demonstrated by the artworks and creative processes of all participants, which were sometimes seen as indistinction between the fathers and their children, or their false selves. The pilot outcomes strengthen OECD statistics (2020) about exposure of the men to violence during their childhood, and its traumatic effects on their coping skills, mental development, and communication patterns (Sofer, 2009).

Some of the limitations of the study include the small sample size of participating violent men who completed the process. The participation of the fathers in group art therapy for several months, as well as the presence of the group facilitator as a witness, could have affected the research findings. Despite these limitations, the pilot was daring in inviting a controversial, shadowed population to express themselves freely through creative processes with clay at a Prevention of Domestic Violence Center in Israel. It would be interesting to broaden this examination to a larger sample of violent fathers, to further understand non-verbal messages and their impact on inter-generation. This study provides a glimpse into artistic processes as significant research instruments and their dominance in facilitating authentic expression within oppressed populations.

In conclusion, this art-based pilot study provides a sneak peek into the paternal characteristics of violent men and invites broader perspectives for the complex and multifaceted nature of this phenomenon. The themes of coexisting contrasts and false perfection identified through the creative processes and working with clay offer a view of the inner conflicts and struggles that these men may face. Furthermore, the study highlights the potential of art therapy as a powerful tool for exploring and addressing these issues in a safe and supportive environment. The gained sense of success and assurance experienced by the participants suggests that art-based dialogues and reflections may have a positive impact on their perceptions of parenting, which could have far-reaching implications for their families and communities. Overall, this study contributes to the growing body of research on the use of artistic inquiry modes in understanding and addressing complex social and psychological issues.

About the Authors

Israella Klein has a bachelor’s degree in economy and a master’s in art therapy. She took part in the investment capital market in Israel and the economist of Israel finance delegation to the USA. Israella is a painter and a poet who published her first poetry book in 2014. As a mother experienced in special needs, her journey into the therapeutic world of the arts began by working with men in closed wards in a Mental Health Hospital in central Israel. Israella is currently competing her certificate in New Wave Psychotherapy at the Reichman University.

Daniella Barzilay has a bachelor’s degree in special education and psychology, and a master’s in art therapy. She facilitates diagnostic groups, a group for teenagers and a transition group for the army. As a certified art therapist at the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Clinic at Maccabi Health Services in Israel, she treats individuals and provides parental guidance for children and youth with various mental diagnoses and illnesses. Daniella is currently completing her certificate in psychodynamic psychotherapy at Bar Ilan University.

Renana Salmon has a bachelor’s degree in art education, and a master’s in art therapy. She is an art teacher for kids and adults. As a certified art therapist, she treats children with various mental health issues through the ministry of education, in Israel. Renana is an oil painter artist focusing on contemporary social issues.

Dr. Michal Lev is a board-certified art therapist, supervisor, and a certified family psychotherapist. She is a faculty lecturer at the graduate art therapy program at Ono Academy–ASA in Israel, advising students in their seminar thesis and promoting art-based pedagogy and research. Dr. Lev is an Executive Committee member in the International Association for Creative Arts in Education and Therapy (IACAET). In her established private practice for couples and families Michal incorporates expressive therapies to deal with intimacy issues and promote wellbeing. Her published research and presentations focus on intimacy, art-based research, and creative process-oriented pedagogy.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: michlev@gmail.com; Tel.: +972(54)6616280; www.levmichal.com

References

Agyei, E. O., Dika, M. D., Donkor, K., & Amoanyi, R. (2021). Usage of clay in depicting facial expressions. International Design and Art Journal, 3(2), 174–183.

Alser, D. (2011). The relation between the caregiving systerm and parental capacity to involvement of a divorced father with his children. Tel Aviv University. https://shared-parenting.co.il/wp-content/uploads/2016/.

Arnheim, R. (2004). Art and visual perception: A psychology of the creative eye, rev. and expanded ed. University of California Press.

Bancroft, L. (2014). When father hurts mother: How to help children exposed to domestic violence. Poalim.

Bat-Or, M. (2010). Clay sculpting of mother and child figures encourages mentalization. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 37(4), 319–327. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2010.05.007.

Bat-Or, M., & Grenimann-Bauch, N. (2017). Paternal representations and contemporary parenthood themes through clay figure-sculpting task among fathers of toddlers. The Arts in Psychotherapy (56), 19–29.

Beauregard, C., Tremblay, J., Pomerleau, J., Simard, M., Bourgeois-Guérin, E., Lyke, C., & Rousseau, C. (2020). Building communities in tense times: Fostering connectedness between cultures and generations through community arts. American Journal of Community Psychology, 65(3–4), 437–454.

Ben Porat, E., Gilber, A., & Dekel, R. (2018). Research report: The experience of violent men who receive help in medical and domestic violence prevention centers: What helps with help? A final report submitted to the Ministry of Labor, Welfare and Social Services.

Betensky, M. (1977). The phenomenological approach to art expression and art therapy. Art Psychotherapy, 4(3–4), 173–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-9092(77)90033-3.

Bowlby, J. (2005). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory, vol. 393 Taylor & Francis.

Carmel, Y. (2019). Trapped: Children exposed to domestic violence. In C. Yifat (Ed.), From Theory to Implementation. University of Haifa.

Cohen, H. (2004). Intimate Violence: The emotional world of bashing men. Social Security, 65, 146–149. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23276032.

Cohen, M. (2016). Illusions of the narcissistic mirror: An observation of interpersonal relationships between people suffering from emotional blindness. Hebrew Psychology. https://www.hebpsy.net/articles.asp?id=3361.

Dalley, T., Case, C., Schaverien, J., Weir, F., Halliday, D., Hall, P. N., & Waller, D. (2013). Images of Art Therapy (Psychology Revivals): New Developments in Theory and Practice. Routledge.

Dotan, N. (2016). To change in the AMT—The Shachmat program. Hebrew psychology. https://www.hebpsy.net/articles.asp?id=3484.

Duckrow Fonda, S. (2017). Filmmaking as artistic inquiry: An examination of ceramic art therapy in a maximum-security forensic psychiatric facility, Publication Number 1884348858. Dissertation, Lesley University. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. http://ezproxyles.flo.org/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxyles.flo.org/docview/1884348858?accountid=12060.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society, 1st ed. Norton.

Gil, S. (2018). ‘Less but painful’: A psycho-mythical study of conjugal love, Naftolia and her crises. Hebrew psychology. https://www.hebpsy.net/articles.asp?id=3661.

Govoni, D., Teoli, L., & Summer, D. (2022). Renegotiating problematic relationships: An art-based sculpting method to address reactivity across disciplines. Journal of Applied Arts & Health, 13(2), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1386/jaah_00104_1.

Gurvitz, D., & Arab, D. (2012). The Encyclopedia of Ideas: Culture, Thought, Communication. Bavel.

Israeli, N. (2020). Manhood and fatherhood [Interview]. The First Social Radio. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PAyXfXCZsvc.

Kindlon, D., & Thompson, M. (2009). Raising Cain: Protecting the emotional life of boys. Ballantine Books.

Kossak, M. (2021). Attunement in expressive arts therapy: Toward an understanding of embodied empathy, 2nd ed. Charles C Thomas Publisher.

Lance, O. (2011). Mental observation. Amatzya.

Lev, M. (2020). Art as a mediator for intimacy: Reflections of an art-based research study. Journal of Applied Arts and Health, 11(3), 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1386/jaah_00041_7.

Lev, M. (2021). Painting an art-based research of intimacy. In T. Yaguri, D. Merari (Eds.), Art in Action: Teaching, Training, and Research in Art Therapy. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Lev, M. (2022). Artmaking resilience: Reflections on art-based research of bereavement and grief. Creative Arts in Education and Therapy (CAET), 8(1), 126–138. https://doi.org/10.15212/CAET/2022/8/1.

Lev, M., Kats, A., & Navoth, G. (2021). In sickness and death: An art-based pedagogical research. In T. Yaguri & D. Merari (Eds.), Art in action: Teaching, training, and research in art therapy (pp. 78–98). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

McNiff, S. (2014). Art speaking for itself: Evidence that inspires and convinces. Journal of Applied Arts & Health, 5(2), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1386/jaah.5.2.255_1.

McNiff, S. (2018). Philosophical and practical foundations of artistic inquiry: Creating paradigms, methods, and presentations based in art. In P. Leavy (Ed.), Handbook of arts-based research (pp. 22–36). Guilford Press.

Nan, J. K., Hinz, L. D., & Lusebrink, V. B. (2021). Clay art therapy on emotion regulation: Research, theoretical underpinnings, and treatment mechanisms. In The Neuroscience of Depression (pp. 431–442). Elsevier.

OECD. (2020). Taking public action to end violence at home: Summary of conference proceedings.

Orbach, N. (2017, December 4). What is your favorite art medium? The Good Enough Studio. http://thegoodenoughstudio.com/what-is-your-favorite-art-medium/.

Reel, T. (1999). I don’t want to talk about it: About the hidden legacy of male depression and how to break free from it. Am Oved.

Richards, M. C. (2011). Centering in pottery, poetry, and the person, illustrated ed. Wesleyan University Press.

Sholt, M., & Gavron, T. (2006). Therapeutic qualities of clay-work in art therapy and psychotherapy: A review. Art Therapy, 23(2), 66–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2006.10129647.

Skop, M., Darewych, O. H., Root, J., & Mason, J. (2022). Exploring intimate partner violence survivors’ experiences with group art therapy. International Journal of Art Therapy, 27(4), 159–168.

Sofer, Z. (2007). Men who use violence against their partners: Theories, classification and treatment. Hebrew psychology. https://www.hebpsy.net/articles.asp?id=1429.

Sofer, Z. (2009). Men who use domestic violence and post-traumatic stress disorder. Hebrew psychology. https://www.hebpsy.net/articles.asp?id=2191.

Weir, P. (1995). The role of symbolic expression in the context of art therapy: A Kleinian approach. In T. Dally, C. Case, J. Schavarien, F. Weir, D. Halliday, N. Hall, & D. Waller (Eds.), Art therapy new developments: Theory and practice (pp. 128–148). Ach.

Yalom, E. (2002). The gift of therapy. Kineret.

Yassur-Borochowitz, D. (2003). Intimate violence: The emotional world of male batterers. Resling.