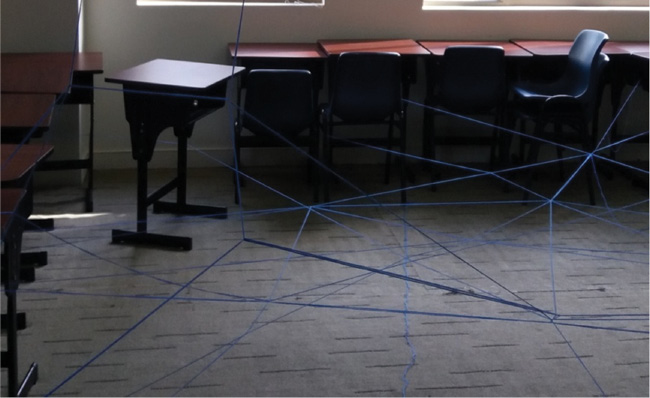

FIGURE 1 | Projection, image, and metaphor in session 7.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2022) 8(2):200–212. | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2022/8/24 |

Bridge to the Silence—Integrative Dramatherapy with Selective Mutism

静寂之桥—通过整合戏剧疗法治疗患有选择性缄默症的儿童

FairSky Foundation, United States

Abstract

This article is presented as a clinical case study in research and the arts that explores the journey of a 7-year-old girl with selective mutism, and her growth through an integrative intervention that combined dramatherapy, systemic, behavioral, and attachment-informed approaches. Sessions took place in Shanghai, China. Gorla et al. (2017) [Without words. Different children in different contexts (Trans.). A.G. Editions] and Perednik (2016) [The selective mutism treatment guide: Manuals for parents, teachers, and therapists: Still waters run deep. Oaklands] propose that the significant others of a person with selective mutism can become therapeutic agents of change, and through this lens, the child’s family, peers, and school staff became involved. Through the use of play and the therapeutic relationship and the coming together of specialties and community, it is posited that the client found her voice again, enhancing her relationships and embarking on a journey of lasting change. The dramatherapy-based, multimodal intervention provides an example of clinical practice intended to assist therapists, parents, schools, and practitioners looking to support an individual with selective mutism.

Keywords: selective mutism, dramatherapy, systemic, behavioral, attachment, family, school/education.

摘要

本文作为一项研究和艺术领域的临床案例研究,利用多种艺术手段辅助治疗了一名患有选择性缄默症(SM)的7岁女孩,对于此个案具体是通过结合戏剧疗法、系统、行为和依恋知情方法进行综合干预。Gorla和她的同事(2017)和Perednik(2016)提出,对于选择性缄默症的患者来说,身边熟悉的人可以成为治疗中的一部分。通过这种视角,这位儿童在社会与家庭环境中接触到的老师,同伴或家人可以成为辅助治疗的催化剂。通过使用游戏互动的方式,还有家庭、学校和社区的参与,治疗关系得到提升,治疗效果有显著的提高。患有选择性缄默症的这位儿童“Octavia”重新找回了她的“声音”,并加强了自我对人际关系的处理能力和沟通能力。文章中,以戏剧疗法为基础的多模式干预给基于临床背景下的戏剧疗法提供了一个实例,以此希望能启发家长、治疗师、学校和相关从业者,从而更好的支持选择性缄默症患者。

关键词:选择性缄默症, 戏剧疗法, 系统疗法, 行为疗法, 依恋疗法, 家庭, 学校/教育

Introduction

This article presents as a clinical case study in research and the arts and explores an integrative dramatherapy intervention for a 7-year-old girl with selective mutism. The sessions took place over 2.5 years in Shanghai, China, while I was living there, and for the purpose of this article, the client will be called Octavia. Having an integrative approach enables a therapist to select from varied theories and practices that aim to correspond with the client’s needs, preferences, and context. Interventions are individualized, and for this child, Gorla et al.’s (2017) systemic approach became central to my work, along with Perednik’s (2016) ecological and cognitive behavioral model. Their frames invite the client and those in their close environment, such as family and school, to be included in the intervention, rendering them key participants and therapeutic agents of change. This article explores how these approaches unfolded and were combined with dramatherapy, play, and attachment to form a robust and cohesive intervention for Octavia’s holistic development and environment.

Settings

The therapy center offered multidisciplinary therapeutic, educational, and training services to individuals, groups, and families. They served the local and international communities in Shanghai and the greater area. Since therapy is uncommon in China, only few therapy services are available; thus, the organization had developed an environment of inclusivity and adaptability in order to meet the diverse needs of the community. The therapy center worked with a wide range of needs, backgrounds, languages, and ages in varied settings to make services accessible. It is in this environment of versatility that I came to initiate a wide-scale approach in the client’s school, and it is with the school’s openness and support that this intervention could be realized. It was an international, English-speaking school that included regular Mandarin lessons. Most of our therapy sessions were at this school, others at the therapy center, and a few at the client’s home.

Selective Mutism

Individuals with selective mutism experience anxiety, which leaves them unable to speak in certain situations, especially social ones, while having an ability to speak (Woliver, 2009). Social anxiety is commonly associated with selective mutism, and for children with selective mutism, school is often the most difficult place to speak in (Shipon-Blum, 2009). Selective mutism is commonly first noticed in kindergarten and primary school while developing in the early years (Marschall, 2015).

Speaking in situations that they experience as uncomfortable or threatening triggers and enhances their anxiety (Gorla et al., 2017). When theorizing on anxiety, LeDoux (1996) suggests that fear is its driver, and this corresponds with Woliver (2009), who proposes that selective mutism can bring fears of being judged and humiliated for what one thinks, says, and who one is. Magagna (2012a) adds that fears amplify anxiety to a level that can be unbearable for those who experience selective mutism.

Shipon-Blum (2009) writes that being silent in selective mutism is an attempt to protect oneself as it bypasses the distressing situation of communication. In doing so, the silence becomes a coping response to overwhelming emotions. The silence is not driven by choice—it is reactive and unconscious (Woliver, 2009). There then develops a disconnect from the pain that remains avoided through emotional numbing and not thinking; meanwhile, the inner voice that might have helped to make sense of these feelings also becomes silenced (Magagna, 2012a). In anxiety, there also develops repeated anticipation that disrupts the regulation of affect (Ginot, 2015). From these perspectives, what was at first a defense for self-protection in selective mutism turns into a pattern, as a current tending toward silence.

Client History

Octavia was 7 years old when she came to our services. She had been comfortable speaking at home with her family and was nonspeaking in most other contexts since around the age of 3 years old. The family had moved from Italy to Shanghai when she was 2.5 years old, and the family spoke Italian at home. Several changes were also taking place at that time, including the birth of her brother and Octavia starting school in a new language (English) with a teacher who was described as not supportive of her English learning, and critical of her using Italian when first trying to communicate. It was soon after these series of events that she lost her voice in school and then in most other contexts. Having attended an English-speaking school from her early years, she was doing well academically and had become proficient in English over time. A prior assessment by another practitioner had also ruled out any speech and language delay. Our therapy sessions were in English.

Dramatherapy

There appears to be limited literature on dramatherapy and selective mutism. In a case study by Oon (2010), she portrays how dramatherapy merges with behavioral techniques and relationship building to enable vocalization, self-esteem, spontaneity, and sociability. Hoey (2005) utilizes play and stories, and Owen (2008) demonstrates how story-making, play, and role can help develop communication. Owen (2008) cites a research paper by Nissan (2005) that focuses on play, story, embodiment, and projection and how it quickly helped a young girl with selective mutism to release emotional turmoil and start vocalization.

I turned to other practices for further examples. The physician Shipon-Blum (2009), who specializes in selective mutism, has observed that many children with selective mutism are highly creative, suggesting their difficulty to speak might lead them to find other ways to communicate. Elsewhere, Shipon-Blum (2001) has also observed that art can be relaxing for them, while increasing their self-esteem. Magagna (2012a), a psychotherapist, describes how working with creativity can help children with selective mutism to process their experiences in a way that bypasses the reliance on words, which for them is already limiting. Fernandez et al. (2014) demonstrate that expressive therapies can foster understanding of the client and stimulate communication between therapist and client. Wormald et al. (2012) add that creative approaches foster links between the child’s internal self and the external world, creating a middle ground that can stimulate exchange and connection with others.

From these perspectives, art and creative-based practices, such as those found within dramatherapy, have rich potential for a child with selective mutism. They may offer alternatives to words while providing new experiences. Creativity might also be familiar and accessible for them, especially as an outlet for emotional release and a way to build a relationship.

Dramatic Projection

In our first dramatherapy sessions, Octavia was invited to use small objects, drawing, and writing for parts of her inner world to be expressed through play, stories, and images (Jennings et al., 1994). As Jones (2007) writes about dramatic projection, parts of the self are turned into metaphors, allowing for a safe distance to be created between the self and the material, which in turn makes it easier to access feelings. This felt a particularly useful way to help Octavia reconnect with her thoughts and feelings, to have a channel through which to explore parts of herself that had become seemingly frozen.

Vignette 1: Session 7

In the first year, sessions were mostly on a 1:1 basis and occasionally included Octavia’s mother. These vignettes are from these 1:1 sessions. Octavia enjoyed being creative, and this showed in her enthusiasm and comfort with the creative process. In the seventh session, she was invited to explore how she sees herself and her world with her family in Shanghai, to identify her feelings and perspectives. She first chose objects to represent each family member and then did a drawing from this. All family members were tied, and she helped me understand that someone/something had tied them. This image can be seen in Figure 1 (the names and identifying features have been removed for confidentiality).

FIGURE 1 | Projection, image, and metaphor in session 7.

Case Discussion

Over the first sessions, there were recurrent themes in her stories and images. Characters often traveled between distinct places and/or got stuck. The repeated theme of being “stuck” suggested she was trying to work through this impasse (Ryan & Edge, 2012). This appeared to capture an aspect of anxiety and the role of silence that had become stuck inside of her and, consequently, how the family might also be feeling stuck regarding how to help. There also appeared to be parallels between the artwork and her life, as can often be seen in projective images in dramatherapy (Jones, 1996). Octavia had difficulty in responding when I shared with her these hunches, but discussions with parents regularly affirmed the parallels. Over the sessions, characters began changing from being stuck to finding liberation. Projective play started restoring her spontaneity with social engagement, where her play progressed from solo with little eye contact to interacting more flexibly. This widened the options for her, to play and experiment with different ways of relating and how else things could be.

Embodiment

Anxiety inhibits the ability to decide and act and in selective mutism—it paralyzes physically (Gorla et al., 2017). This rise in anxiety appeared to occur for Octavia especially in the first months when I asked her opinion, feelings, or thoughts. She would shrug, have a glazed look, and a limp body until we resumed working with metaphor. Looking directly at her experience and thinking with words seemed to be triggering anxiety, followed by avoidance as a way to cope with it. Children with selective mutism sometimes appear to lack facial expression, which according to Gorla et al. (2017) reflects feelings of being frozen when they might want to talk but cannot. Consequently, staying with metaphor was particularly fitting, and the body became another route for her to explore her inner world. Embodiment in dramatherapy can open access to one’s experience and offer a mode of communication that uses the body to express one’s feelings and life story (Jones, 2007).

As Rothschild (2000) says succinctly, emotions are an experience of the body; they recruit the sensory and autonomic nervous systems and the brain. Fernandez et al. (2014) examine how expressive therapies can help children with selective mutism, as it activates the body’s physical participation while helping to release tension and decrease anxiety. Van Der Kolk (2006) highlights the importance for clients to discover that it is safe to have feelings and physical sensations, as this can reduce immobilization and start the process of self-regulation. Embodiment in dramatherapy aims to safely reactivate feelings that lie in the body, without getting the client overwhelmed (Jones, 2007). As Rowe (2000) describes, the body can also physicalize metaphor in dramatherapy, which provides further ways to explore a client’s images. The following vignette exemplifies this process.

Vignette 2: Session 16

In thinking about Octavia’s image of her and her family being tied, I brought string to a later session. Through her initiative, Octavia started attaching it across the room until it was filled with strings, as shown in Figure 2. She pulled the strings, experimenting with decisions and the impact these actions had on her and the environment. She created an intricate imagery that she was compelled to walk through and, in order to do so, needed to problem solve and pace herself. She got caught in the strings and found ways out. After some time, I said it made me think of a web, and she responded with a big smile and a confirming nod. I asked, “if this web were your home, where would you be?” She placed herself in an area that was spacious between strings and easy to stand in, close to the middle of the room, and she smiled. I then asked, “What if this web were your school, where would you place yourself?” She went to the edges, stayed on the outside of the web and took a posture and facial expression that showed unease. After this, she untied the strings and intentionally played at tangling and untangling herself.

FIGURE 2 | Image in physical space and embodiment in session 16.

Case Discussion

Through embodiment, Octavia went through the motions of getting stuck, navigating, and overcoming this obstacle. She imagined what the strings could represent and expressed with her body her emotional response, identifying what seemed for the first time; a deeper sense of how she felt in school. This possibly helped her gain embodied knowledge, one that is gained only through the experience of the body (Nagatomo, 1992). Gradually, over the sessions, Octavia explored and expressed a wider range of feelings with her family and I, and her body became more fluid and animated. The long-term dramatherapy goals were refined to include emotional expression and self-regulation, reducing anxiety, and developing autonomy, confidence, and social interaction.

Integrating Systemic and Behavioral Approaches

One year later, Octavia’s mother and I agreed to integrate further approaches that specialize in children with selective mutism. We embarked on a remote collaboration with Dr. Gorla, with whom the family shared the culture and native language of Italian, and this eased the parents’ communication and further support to Octavia. We had consultations together and separately. Dr. Gorla offered us systemic frames from her work (Gorla et al., 2017) and Perednik (2016), which became pivotal to the intervention. As selective mutism presents differently in different situations, both emphasize the need to work with the child’s family and to form a team with the school, because it is often where selective mutism begins and persists. They see the child as part of a larger system that can be supported to change with new interactions, through the help of a therapist and team collaboration. In this way, the child and their environment gain tools to effect change, which can build on and continue the therapeutic process.

Because of the focus of this article, I will only briefly mention that, at that time, I also started facilitating family sessions with Octavia, her parents, and brother (Dallos & Vetere, 2009). As Gorla et al. (2017) assert, working with families can create a greater thinking space and atmosphere that is receptive to feelings that can help the child with selective mutism to work through their difficulties. It can also assist the family to develop their inner resources (Magagna, 2012b). How the family responded and felt as well as determining what they wanted, helped further develop family-related goals.

Part of the dramatherapy sessions also shifted at that time to include and adapt activities from Perednik (2016). Her model is ecological and cognitive-behavioral, meaning it is context-based and assists an individual with selective mutism to be exposed in small gradual steps toward communication, with people from their immediate environment, including family and school. The aims are to help expand the child’s feelings of safety in the presence of others through offering opportunities for communication. New actions can be practiced while experiencing small doses of anxiety within a safe relationship and environment, thus helping to keep the feelings manageable. Fear-based expectations can be gently dismantled, showing that exposure does not necessarily lead to a negative outcome and can be linked to new experiences of safety (Santini et al., 2001). In this way, habitual responses can be stretched, and communication and relationships enhanced.

Shipon-Blum (2009) also uses exposure with selective mutism, saying it aims to match the client’s readiness so they do not become overwhelmed. It was important to observe Octavia’s comfort level and window of tolerance, so that she could remain in her optimal zone where her emotional and physiological arousal could be activated without becoming dysregulated (Siegel, 1999). Staying within this zone helps it to be gradually expanded. With practice, Octavia gradually moved away from the paralysis of her anxiety, as will be demonstrated in the next sections.

Perednik’s (2016) phases and goals:

Every time Octavia achieved a communication goal, we practiced it in different activities pitched at that level until she was ready for the next goal. She showed readiness through being joyful and initiating more sound than the activity asked for. I remained attuned to what was happening for her and her needs in order to align with what she was ready for (Erskine, 1998). The phases were followed flexibly and helped oversee progress. Additionally, before being aware of this model, we had already begun the first four steps, albeit steps 2 to 4 had not been our goals and were rather outcomes that sprung from our interactions. Furthermore, when starting to use this model, the sessions temporarily moved from her school to our therapy center, since Octavia had not built communication patterns there, and we felt it would reduce her expectations and help build a new chapter (which it did).

The activities in Perednik’s (2016) model are interactive, experiential, and play-based, and they invite the therapist to be an active participant in the play with the child. These qualities are also found in dramatherapy, which makes these approaches fit well together. Play is a major language through which children learn and communicate (Winnicott, 1971). It reduces pressure and anxiety and enhances spontaneity and pleasure (Brown, 1995). In dramatherapy, play is also seen to contribute to self-discovery and mastery of new skills (Jones, 2007). Play was central throughout this intervention and helped Octavia to relax. It also appeared to assist interactions between Octavia and the other participants in the process. Sessions combined activities from dramatherapy, Perednik’s (2016) activities, Dr. Gorla’s suggestions offered during consultations, Octavia’s suggested creative games, and others we co-developed. Dramatherapy also continued to support Octavia’s feelings and thoughts and provided a key lens to make meaning of the process.

Intermediary as a Relational Bridge

Gorla et al. (2017), Perednik (2016), and Shipon-Blum (2009) recommend starting verbal exchanges with an intermediary, but they use different terms for this. In principle, an intermediary is a support person with whom the child with selective mutism is already comfortable with and speaks with and who is present when introduced to speaking for the first time with someone else. Their presence, play-based prompts, and guidance can aid the child’s speech with the other person. Once the child is comfortable to engage verbally with the new person, the intermediary no longer needs to be present during their interactions. Gorla et al. (2017) explain this role as a relational bridge, where the focus is not facilitating speech but rather helping to build a relationship.

Octavia’s mother was the relational bridge for us. For a few weeks, the three of us were in the sessions playing hangman through Chinese Whispers. Octavia whispered one letter at a time to her mother who then whispered the letter to me. One day, we invited Octavia to whisper the letter to me instead, and she agreed, which marked the beginning of her verbal communication with me. Over a few weeks, Octavia’s whisper became easier to hear, and no prompt was needed to elicit communication. Each session saw progress, it went from a letter to a word, to a sentence, to several sentences, and a flow in back and forth verbal communication. She became actively engaged in verbal exchanges with me, had regular eye contact, and showed joy and excitement in expressing herself. With these developments, we agreed the mother’s attendance in sessions could come to an end, to which Octavia adapted very well. Speech became a usual response for her that offered direct feedback of her achievements, which increased her confidence. Her autonomy and agency grew noticeably, and later, we resumed sessions in school to help transfer these changes.

Attachment and the Relational Bridge

I remained mindful that selective mutism manifests in the presence of others, and it was crucial for our relationship to offer trust and a sense of safety for Octavia to be able to engage, explore, and take new risks (Ogden et al., 2006). As Van Der Kolk (2014) describes, a context of safety decreases reactivity and mobilizes the body, allowing it to recover its capacity to experience relaxation and reciprocity in relationships. In this way, the relational bridge is pivotal and helps build safe spaces within which interactions and relationships can flourish.

Vignette: At School with Peers and Adults

Later in the intervention, Octavia was supported to speak with staff and peers at school. While I facilitated activities that invited verbal expression with others, at the beginning, Octavia often sought eye contact with me. She would look at me intently, as though asking, “Are you there with me, can I take this risk?” I would stay with her with a gentle gaze, and her readiness would concretize through whispered responses, increased social spontaneity, and pleasure.

Discussion

With each new encounter, her searching gaze toward me reduced and became no longer needed. Attuning and affirming her needs had appeased her and oriented her to safety, offering co-regulation (Rothschild, 2000). This exemplifies the process by which external regulation with a safe other becomes internalized and lends itself to self-regulation and coping (Schore, 2001). Over time, Octavia was more comfortable and started speaking and playing more independently and confidently with others.

Developing the School Environment

School Team

The mother and I introduced Gorla et al.’s (2017) and Perednik’s (2016) models to the school and formed a key support team that included Octavia’s grade teacher(s), school principal, school counselor, and later a learning support teacher. We held meetings where observations were shared, and objectives and strategies were developed with our communication upheld between meetings.

Octavia’s third-grade teacher first became involved in implementing strategies. Speech goals were developed with her that related to educational goals. Octavia was first given homework to identify her reading level. She would record herself reading out loud at home and bring this to school for them to listen to privately. The recording also aimed to help Octavia become more comfortable with hearing her voice in school and having it heard by others, which would make it easier to speak in school. The challenge increased incrementally. After five homework recordings, Octavia started reading and speaking more than what she had been asked for, which suggested she was ready for more—similar to what had occurred in dramatherapy.

After several weeks, the teacher asked her a question using the game of Chinese Whispers, and Octavia responded openly, which marked the beginning of their verbal exchange. They began weekly play time after school in their classroom, and this helped them speak more freely and build their relationship. Following this, Octavia was invited to start a similar recording homework with her art teacher. This quickly led to her whispering with this teacher too.

While this unfolded, Octavia and her mother also played in her classroom after school to help her become more comfortable in school. The teacher was occasionally present during those times, working at the back of the room discretely while hearing Octavia’s voice (Gorla et al., 2017; Shipon-Blum, 2009). Octavia’s mother was dedicated and invested in helping her daughter. She organized playdates, restructured family rules, helped Octavia’s emotional and social development, and supported here in many more ways than I could name in this article.

Octavia was invited to widen the circle of people with whom she was comfortable with, and gradually this involved more staff, classmates, and peers. Sharing recordings of her voice usually provided a scaffold towards verbal interaction. The school counselor played a key role as ally, coordinator, and intermediary between Octavia and several individuals in school, including the librarian, music teacher, and others. Octavia’s third-grade teacher acted as an intermediary for her fourth-grade teacher, whom Octavia had known through another role. From their first three-way meeting, Octavia spoke with her fourth-grade teacher, which remained throughout the year.

Peers in School and Therapy

To develop communication with peers in school, Octavia was asked by her fourth-grade teacher to record homework, which would be heard by him and, increasingly, her classmates. She shared with one person at a time, until everyone heard her recorded voice in class.

Meanwhile, a portion of the dramatherapy sessions became dedicated to small group work with peers and friends who attended one at a time. The format was similar; we played creative activities from prior sessions and others that arose through being child-led and collaborative. These interactions helped her develop social skills and assertiveness. Through these sessions, Octavia started speaking with peers. She also resumed speaking with an old friend, which had not occurred for years. An image will stay with me of their walking down the hallway after a session, chatting enthusiastically with laughter.

In the 1:1 dramatherapy portion, Octavia continued exploring the different areas in her life. We also discussed creating opportunities to practice verbal communication with peers in school to help her feel increasingly comfortable. Octavia identified periods that could fit well with this objective. She agreed that I share this with her teacher, who then incorporated it in the day. The teacher was very supportive and initiated small group activities such as Chinese Whispers to help her vocalize. Soon after she had spoken with a peer in therapy for the first time, she was speaking with peers in class too. Octavia’s speech grew leading to verbal interactions that became a process of its own that no longer needed the teacher’s prompt. Octavia was finding her voice with peers and friends in and out of school.

In addition, an initiative was taken later in the year when Octavia was ready to engage with more peers. The school counselor acted as an intermediary and introduced the learning support teacher to Octavia. When they spoke easily together, Octavia was invited to join a small after-school peer group that this teacher was facilitating. Almost instantly, Octavia was able to communicate verbally and playfully with all the students in her peer group.

Conclusion

In working integratively with dramatherapy, systems, attachment, and behavioral approaches, a bridge reached a child who had been caught in the silence of selective mutism. Octavia reunited with parts of herself that had been muted for several years. She developed self-awareness, self-regulation, inner calm, and her anxiety reduced. Her verbal and nonverbal communication became increasingly spontaneous, with an ability to initiate, maintain, and build social engagement in and out of school. Her confidence and agency grew, actively contributing to the co-creation of the environment she was a part of. For the family, their reflectivity and responsiveness to emotions grew as did the parents’ understanding of Octavia.

By working with Octavia’s family and school, Octavia transformed with the systems equipped to continue the process going forward. The relationships between the therapist and parents, school, and intermediaries, with the child at the center, were vital. Structure and flexibility provided predictability with opportunities for change. Finally, the arts and play-based process helped develop safety and empowered Octavia (and possibly others) to take risks, which appeared to increase social reciprocity. Relationships flourished and new ones were built. Further research could explore the impact that this integrative approach may have on systems, such as schools and families.

Our partnership came to an end when I left the country, and before my departure, I arranged with Octavia and the family a careful handover. Currently, Octavia’s mother is happy for me to share that progress has continued steadily. Octavia’s anxiety is very low, her independence and social engagement have grown, and she is enjoying school and friendships, speaking with more ease in school and freely with mostly anyone outside school. As the multimodal and creative approaches mentioned can be adapted by parents, therapists, teachers, and practitioners, it is my hope that this case study serves a wide range of audiences who support/wish to support individuals with selective mutism.

Acknowledgement

There is no funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

About the Author

Sarah Bilodeau is an HCPC (UK) and RDT (USA) registered Dramatherapist. She combines her practice with her curiosity for learning about different places through living in them. She has worked in different countries which has helped shape her systemic and culturally-informed lens. Her approach is integrative and adapted to each person’s needs, age, preference and context. She sees individuals, families and groups who experience varied difficulties. She also offers consultations, workshops and trainings to parents, professionals and communities in English, French, in person, and online.

References

Brown, S. (1995). Through the lens of play. Revision, 17(4), 4–14.

Dallos, R., & Vetere, A. (2009). Systemic therapy and attachment narratives: Applications in a range of clinical settings. Routledge.

Erskine, R. G. (1998). Attunement and involvement: therapeutic responses to relational needs. International Journal of Psychotherapy, 3(3), 235–244.

Fernandez, K. G., Serrano, K. C. M., & Tongson, M. C. C. (2014). An intervention in treating selective mutism using the expressive therapies continuum framework. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 9(1), 19–32.

Ginot, E. (2015). Neuropsychology of the unconscious: Integrating brain and mind in psychotherapy. W. W. Norton & Company.

Gorla, C., Lus, S., & Trivelli, F. (2017). Without words. Different children in different contexts (trans.), Senza Parole. Bambini diversi in contesti diversi. A. G. Edition.

Hoey, B. (2005). Children who whisper: A study of psychodramatic methods for reaching inarticulate young people. In A. M. Weber (Ed.). Clinical applications of drama therapy in child and adolescent treatment (pp. 25–44). Brunner-Routledge.

Jennings, S., Cattanach, A., Mitchell, S., Chesner, A., & Meldrum, B. (1994). The handbook of dramatherapy. Routledge.

Jones, P. (1996). Drama as therapy, theatre as living. Brunner-Routledge.

Jones, P. (2007). Drama as therapy: Theory, practice and research (2nd ed.). Routledge.

LeDoux, J. E. (1996). The emotional brain. Brunner/Mazel.

Magagna, J. (2012a). The child who has not yet found words. In J. Magagna (Ed.). The silent child: Communication without words (pp. 91–113). Karnac Books.

Magagna, J. (2012b). Extended family explorations using dreams, drawings, and play when the referred child does not speak. In J. Magagna (Ed.). The silent child: Communication without words (pp. 117–137). Karnac Books.

Marschall, V. (2015). Words. Thoughts, reflections, stories linked by the thread of selective mutism (trans.), Les Paroles. Pensées, réflexions, histoires liées par le fil rouge du mutisme sélectif. Sander, S., Préface (pp. 11–14). A. G. Editions.

Nagatomo, S. (1992). An Eastern concept of the body: Yuasa’s body scheme. In M. Sheets-Johnstone (Ed.). Giving the body its due (pp. xi, 233). State University of New York Press.

Nissan, S. (2005). Heuristic research: The unfinished roles. Unpublished master’s thesis, Concordia University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the body: A sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy. W. W. Norton & Company.

Oon, P. P. (2010). Playing with Gladys: A case study integrating drama therapy with behavioural interventions for the treatment of selective mutism. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 15(2), 215–230.

Owen, M. (2008). Communication through story: Story-making with a child diagnosed with selective mutism. Library and Archives Canada–Published Heritage House.

Perednik, R. (2016). The selective mutism treatment guide: Manuals for parents, teachers, and therapists: Still waters run deep. Oaklands.

Rothschild, B. (2000). The body remembers: The psychophysiology of trauma and trauma treatment. W. W. Norton & Company.

Rowe, N. (2000). Philosophy in the flesh: the embodied mind and dramatherapy. Dramatherapy, 22(2), 13–17.

Ryan, V., & Edge, A. (2012). The role of play themes in non-directive play therapy. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(3), 354–369.

Santini, E., Muller, R. U., & Quirk, G. J. (2001). Consolidation of extinction learning involves transfer from NMDA-independent to NMDA-dependent memory. Journal of Neuroscience, 21(22), 9009–9017.

Schore, A. (2001). The effects of early relational trauma on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal, 22, 201–269.

Siegel, D. (1999). The developing mind. Guildford Press.

Shipon-Blum, E. (2001). The ideal classroom setting for the selective mute child. Selective Mutism Anxiety Research & Treatment Center Publishing.

Shipon-Blum, E. (2009). Understanding selective mutism: Guide for parents, teachers and therapists (trans.), Comprendre le mutisme sélectif: Guide à l’usage des parents, enseignant et thérapeutes. Chronique Sociale.

Van Der Kolk, B. A. (2006). Clinical Implications of neuroscience research in PTSD. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1071(1), 277–293.

Van Der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and the body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Publishing Group.

Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Playing and reality. London: Routledge.

Woliver, R. (2009). Alphabet kids—From ADD to Zellwegger syndrome: A guide to developmental, neurobiological and psychological disorders for parents and professionals. Jessica Kingsley.

Wormald, C., Le Clézio, N., & Sharma, A. (2012). Roar and rumpus: engaging non-speaking children through stories and songs. In J. Magagna (Ed.). The silent child: Communication without words (pp. 313–343). Karnac Books.