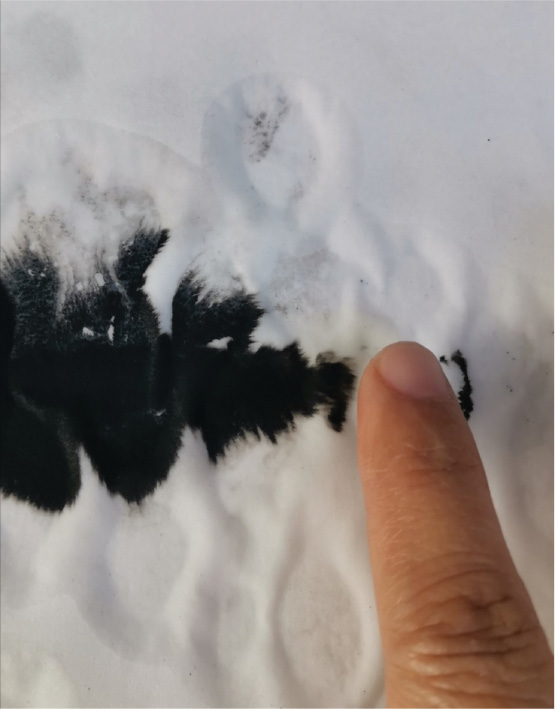

FIGURE 1 | Water trace.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2022) 8(2):158–172 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2022/8/18 |

Ink Talks: Processing Compassion Fatigue through Culturally Relevant Arts-Making

墨说:通过文化相关的艺术创作来处理同情疲劳

The University of Auckland, New Zealand

Abstract

This paper explores the power of the arts and the spiritual support of one’s own culture in helping an immigrant arts therapist process professional compassion fatigue. Through autoethnographic narrative and arts-based inquiry, I intend to dive into the emotional distress arising from this immigrant therapist’s experience of compassion fatigue in a creative way. In this cultural and arts-based research journey, I immerse in my personal/professional experience through the arts-making process as an immigrant arts therapist to explore expression, transformation, and enlightenment as ways of processing compassion fatigue. Through this insightful personal journey, I argue that the importance of self-disclosure and self-exploration through culturally relevant creativity might enhance the wellbeing of the immigrant therapist. In addition, this study attempts to discuss the topic of therapists’ compassion fatigue through a decolonizing lens and with Eastern philosophical perspectives.

Keywords: culturally relevant, arts-based inquiry, immigrant therapist, compassion fatigue

摘要

本文探讨了艺术的力量和文化的精神支持在移民艺术治疗师遭遇同情疲劳时的作用。通过民族志个人叙事和艺术本位的探究,作者作为一名移民治疗师,让自己专注在来自同情疲劳经历中的情感困扰中。在这次艺术本位研究之旅中,作者以移民艺术治疗师的身份,沉浸在个人/专业经历的艺术创作过程中,研究同情疲劳的表达、转化和启蒙。通过富有洞察力的个人旅程,我探诉了通过具有文化相关的创造力进行自我表露和自我探索,以及其对于移民治疗师的健康的重要性。此外,本研究试图通过非殖民化的视野和东方哲学的角度来讨论治疗师的同情疲劳这一话题。

关键词: 文化相关, 艺术本位探究, 移民治疗师, 同情疲劳

Entering Compassion Fatigue

In my career as an arts therapist, I have had several moments when I felt a longing to step away from my mental health clinician profession. In the past, all those moments came and went fast. The most recent time, when this thought entered my mind again, I knew it was different. My body was swamped by anxious responses, and my mind was flooded with negative thoughts. As a mental health professional, I am always helping my clients deal with their emotions. However, in this incident, I was overwhelmed by my own emotions. My husband and I planned this couple’s day a while ago. Busy work schedules and endless parenting duties had left us exhausted. When we finally felt a bit relaxed on our couple’s day and were on our way to find a tasty coffee for our afternoon break, I noticed a notification on my phone for a new text message. I could not resist my impulsivity, so I opened the message.

After a few seconds of reading this text, I found myself in shock. The hateful words from this harassing text surprised me. In my arts therapy career, I have dealt with many cases of domestic violence and abusive relationships, and have supported many victims of such cases to gain self-esteem and independence. I heard scary stories from my colleagues about harassment or threats from the angry partners of these victims. Many of these angry people have a history of aggression, drug-dependency, alcoholic tendency, or criminal records. Looking at the text, I realized I had now encountered this kind of situation myself. I tried my best to keep calm, but I was not in the mood to continue the couple’s day with my husband anymore, so we headed home. We did not talk about this at all on the drive back home. My husband knows the ethical boundaries of my profession. When I got home, I emailed my clinical supervisor and my manager requesting a meeting. It was late in the day, and I knew I would not be able to arrange a talk that day. I continued with my day—cooking for the family, cleaning up the kitchen, and preparing my research work for the next day, silently suppressing my emotional distress from this harassing text.

The next day, after a sleepless night, I had meetings with my clinical supervisor and manager and discussed the situation. I tried my best in these meetings to stay calm and discussed all the steps I needed to take for risk management. At the end of the meeting, when I was asked how I was feeling, I suddenly found my body started shaking and my voice had begun to tremble. My emotions flooded into my body. I was not in a state to identify these emotions, instead my mind was telling me one thing: “Run! Run away from all of these!” Suddenly, I could not feel my love for my clients anymore; I could not see my passion for supporting people and the community on their journeys to gain resilience; I could not sense my curiosity and motivation in arts and social transformation. My love, passion, curiosity, and motivation as a therapist were gone.

Many helping professionals in their clinical career have this kind of moment of entering compassion fatigue. Michael Sussman (1995), author of the book A Perilous Calling: The Hazards of Psychotherapy Practice, calls himself a recovering psychotherapist. He points out that doing psychotherapy “poses significant dangers to clinicians” (p. 1). Sussman further argues that if mental health clinicians overlook this issue, the consequential impacts are not only on their professional life, but also their personal life. He identifies that there is a “taboo regarding self-disclosure” in the psychotherapy profession, and mental health clinicians do not talk about the difficulties from their practice (p. 3). Therapists help their clients talk about their emotional challenges as part of their everyday professional life. Therapists often see themselves as experts who help others cope with life’s challenges (Figley, 2002, p. 1439). However, it is challenging for the therapists themselves to speak out about their emotional distress and vulnerability from their practice. In this paper, through autoethnographic narrative, I confront the “taboo regarding self-disclosure” and use arts-based inquiry to explore the topic of compassion fatigue, not as an expert on other’s emotions, but as a wounded professional myself.

Compassion fatigue is defined as a state of tension and preoccupation with traumatized clients by re-experiencing the traumatic events, “avoidance/numbing of reminders and persistent arousal associated with the patients” (Figley, 2002, p. 1434). Compassion fatigue relates to one’s relationships with others (Todaro-Franceschi, 2012, p. 5). Stamm (2002) suggests that compassion fatigue is one of the three components of professional quality of life, alongside compassion satisfaction and burnout. Psychologist Jeffrey Kottler (1989) relates his compassion fatigue experience to “catching cold and flus” from our clients, and he says: “Never mind that we catch our client’s colds and flus, what about their pessimism, negativity…words creep back to haunt us” (p. 8). That day, when I was attacked by the harassing text, these hateful words were creeping into my mind and my body, haunting me and following me everywhere.

I know there is no other way to get around this being haunted feeling. My art is calling me to face this stress and anxiety of being haunted “like tacking through rough waters” (Wicks, 2007, p. 17).

Heavy-Hearted Me

In the meeting with my manager, I asked for some time-off. Although I have informed all my clients about my time-off, I still cannot help checking my emails and phone without any clear purpose. I am tired and emotionally exhausted by my autopilot therapist’s responsibilities. I tell myself: Find a peaceful and safe place to hide from the haunting—the haunting words, the haunting work, and the haunting endless responsibilities for my clients. I sit in front of my art-making table, but I cannot find the motivation and desire to do any art. I feel ashamed. As an arts therapist, I cannot make art! On the wall next to the window, there is a Chinese instrument, a guqin 古琴, I made during my doctoral study. Through the making of this guqin, I reconnected with my ancestral wisdom and strength as an immigrant arts therapist (Wang, 2021). I named this guqin 清心 [purifying my heart], and hoped my guqin can help me push out negativities from my heart. I need my guqin today, but I cannot play any music on it because of my restless mood. Nevertheless, my restless heart craves my guqin’s calm and soulful voice. So, I search for some of my favorite guqin music online and listen to it with my eyes closed. The sound of the guqin always comforts me. The music from ancient times reminds me of what I have treasured and lost—the connection to my culture and my homeland. The guqin music I am listening to is called 归去来兮辞 [Coming home]. In the music, I hear the warm and gentle sound as if a mother is calling her child to return home. I let the music flow into my body. Then, I feel the heavy pumping of my heart. I feel my heart is a patchwork of emotions. I cannot identify these emotions, but I feel the warmness and gentleness of the guqin music embracing my heart and protecting it from the haunting words. While I listen to the guqin music, I listen to my body’s sensations.

Weiss (2004) encourages therapists to listen to the body’s sensations because “your body is constantly talking to you” (p. 85). My body speaks through my embodied memories, what I forget and what I remember (Weiss, 2004, p. 85). I notice the ink stone on my art-making table. I feel a longing to smell the ink. I discovered the comfort of making art with Chinese ink many years ago when I was a trainee arts therapist (Green et al., 2018). In this moment, my embodied sensation takes me back to my embodied memories of the comfort of using Chinese ink. My body tells me that I need this support from my root culture to heal the hurt I have. I listen to my body’s action (Weiss, 2004, p. 86) and pick up a Chinese calligraphy brush but find I am afraid to make any marks on the paper. I dip the brush in clean water, then move it onto a piece of rice paper. The water drops from the tip of the brush and makes a water trace on the paper (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 | Water trace.

Emotion is invisible, but it is real too. Looking at the water trace, I am feeling the invisible emotions in my body. The thin and fragile rice paper now becomes the strong container for my overwhelming emotions. My invisible emotions, like this transparent water, drop onto this paper, as if tears from my heart. “No!” I tell myself: “You need to let these emotions out. Face it! [like tacking through rough waters] (Wicks, 2007, p. 17)”. With this calling in my heart, I dip my brush in Chinese ink, and then, the brush lightly touches the wet rice paper (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2 | Ink mark.

The black ink dot starts growing, quickly invading the space of the clean water mark. Compassion fatigue from this current harassment incident manifests suddenly. Todaro-Franceschi (2012) also notices compassion fatigue typically “manifests suddenly while caring for those who are suffering” (p. 5). These sudden emotions invade my mind, body, and heart without trace. I need to catch them, so I can face them. I continue to put the dark ink marks onto the rice paper, more and more violently. In some moments, I feel I am not painting, but using the brush to stab into the paper. These ink dots become a dark lump. I turn the paper around and around. Then, I suddenly notice something. I add some lines and colors and try to make the shape more defined. A big, dark and heavy heart appears on the paper (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3 | Heavy heart.

Looking at this dark and ugly heart, I feel something heavy in my heart. It is uncomfortable and scary, but I need to catch these invisible emotions. Using my first language, Chinese, I identify them one by one: 怀疑,愧疚,焦虑,放弃,恐惧,逃避,无助,孤独 doubt, guilt/shame, anxiety, abandonment, fear, escape, helplessness, loneliness. From my research of compassion fatigue, I notice it is not uncommon to relate compassion fatigue to a heavy heart. When social worker Karl La Rowe talks about compassion fatigue, he describes it as “having a heavy heart” (Perry, 2008, p. 87). Todaro-Franceschi (2012) refers to compassion fatigue as “heavy-hearted” and burnout as “empty-hearted” (p. 5). As an immigrant arts therapist, I open my heart to other’s pain in my practice because providing therapy to others is a heartful profession. However, at the moment, being an arts therapist has become a heavy-hearted profession for me.

Coming Back to Home

Doubt, guilt, shame, anxiety, abandonment, fear, escape, helplessness, loneliness—the arts-making process helps me to express these negative emotions associated with my compassion fatigue that I have been suppressing since I received that text. Those hateful words made me doubtful: Am I a good therapist? I feel guilty about my impulsive thoughts of abandoning this profession for good. I am ashamed about the possible beginning of apathy in my therapist career. I feel anxious about taking this unplanned time-off because I know it will trigger some of my clients’ concerns about the emotional support they need when I am away. I cannot deny my fear about this possibly being a dangerous situation for myself and even for my family. I cannot look away through my threat response of running away from all negative emotions. I feel I cannot share my struggles and difficulties from my work with my loved ones in my homeland to get comfort and support from them. As an arts therapist, as well as an immigrant, my feelings of helplessness and loneliness are stronger than ever. I am craving physical contact with my homeland and my people on my home soil. With this craving in my heart and body, I dip my fingers in the Chinese ink spontaneously. The coldness of the ink touches the skin of my fingertips. Somehow, this coldness brings me a pleasant sensation in my body—a joyful feeling comes to me. I want to expand this joyful feeling, so I move my “inky” fingers to another piece of rice paper and paint with my fingers. I paint effortlessly, smell the distinctive aroma of ink, feel the stickiness of the drying ink, and listen to the subtle sounds it makes when I touch the rice paper (see Figure 4). Being able to touch the art materials from my homeland comforts me and eases my longing for physical contact with my root culture.

FIGURE 4 | Touch ink.

I paint and paint, moving my fingers between the ink and the rice paper. Then, I start seeing a landscape emerging. It is a small island, with some reflections on the water. My hometown is Hangzhou, a city in the east of China. There is a beautiful lake in the center of my hometown, called West Lake. When I was a little child, my parents often took me to walk around the lake in the evenings, especially on bright moonlit nights. I have special memories of the bright, round moon shining above the lake on the nights of the Moon Festival. I recall the reflection of the moon dancing with the elegant and rhythmic movement of the water’s surface. There are some small islands in West Lake. Many traditional Chinese-style pergolas are on these small islands. On those nights, we could hire a boat to glide around these islands. These pergolas were lit up by colorful fairy lights. As a little girl, I felt I was Alice in a lake wonderland. Now, in my adopted land, arts-making wakens my embodied memories of those beautiful, bright moonlit nights. I quickly pick up the brush again and add details onto my spontaneous landscape painting (see Figure 5). I want to hold these beautiful and calm memories in my present moment.

FIGURE 5 | Memory of the moon night.

In this painting, I have a bright and round moon in the sky. The darkness in my heart was lightened by the shining and warm moonlight of my homeland. On the little island in this painting, although it is an isolated island, there is a solid pergola. I stand in the corner in this painting, so powerless and little. But I can hear people’s laughter from the pergola. The laughter is from my people and my whakapapa (family genealogy in Māori) in my homeland. On this little island, I am not alone. I have my people and my whakapapa in my heart. With arts-making, I can come home, anytime and anywhere. When I am afraid, tired, frustrated or hurt, this home is always waiting for me in my heart. My arts-making will help me to connect with a sense of coming home.

Weiss (2004) encourages therapists to pay attention to self-care by listening to the unconscious through dreams, meditation and arts (p. 86). Many psychotherapists/psychiatrists/scholars have discovered different ways to connect with the unconscious for wellbeing, such as personal writing (Greenspan, 1999), journaling (Progoff, 1992), art-making (McNiff, 1992), and poetry (Edgar, 1978). My embodied sensation guides me to paint with ink, and painting with ink connects me to my embodied memories of my root culture and homeland. Culturally relevant arts-making helps me to listen to my unconscious need to connect to my root culture and homeland for my wellbeing and self-care as an immigrant arts therapist.

Settling into the Land

After the landscape painting, I feel a bit more relaxed. So, I stand up and look out through the window. The view outside of my window is different from that in my hometown. My house in this adopted land, New Zealand, has been my comfort shelter since I moved in about one and a half decades ago. Looking out the window, I see the tree-shrouded views of the typical suburban Auckland scenery. I feel a bit of disappointment because this view pulls me back to reality from the comforting feeling of connecting to my homeland in my arts-making process. It is a sunny day in the middle of the New Zealand winter. The sky is so blue, there are some soft, fluffy, cotton-like clouds floating in the sky. New Zealand’s Māori name is Aotearoa, which means the land of the long white cloud. Looking at these clouds above my adopted land, I wonder if I can capture white clouds on the white rice paper through my Chinese ink. I sit back down at my arts-making table. I drop some water onto the rice paper to make a wet background, then I pick up a brush, dip it into my Chinese ink, and start painting the clouds. The clouds are flowing out from my brush, but they are dark clouds (see Figure 6).

FIGURE 6 | Ink clouds.

I am not satisfied by my ink-dark clouds, so I throw the painting on the floor to dry. Just before finishing this arts-making session, I realize something. I turn the rice paper upside down. Then, from this different angle, these dark clouds become land. I put this painting back on the table and look at it for a long while. In my mind, I am wondering what can be put into this land. I remember my findings from my previous research projects. In one of my book chapters, Poet Tree, I studied my identity formation process as an immigrant therapist through arts-based identity research where I used a transplanted tree as a metaphor for my displacement experience (Wang, 2020). Looking at this unfinished painting, I decide to put a tree into this “ink land.” Outside my window, in my garden, I planted several acer trees because these trees remind me of my hometown. Being the middle of winter, the leaves of my acer trees have just turned rich yellows and reds. Through my brush, my acer tree grows out of this “ink land.” It is strong, sturdy, and beautiful. In my previous research projects, I, as an immigrant therapist, often see myself as a tree protecting the people passing by my life. As an immigrant arts therapist like a grown-up transplanted tree, I provide the shade and cover for my clients for their emotional needs (Wang, 2020). However, as an immigrant arts therapist in recovery from this compassion fatigue, I have no willingness to be a tree anymore. I want to be protected by other trees. At the end, I add myself as a small person standing on this “ink land,” under my large acer tree (see Figure 7).

FIGURE 7 | Ink land and acer tree.

Looking at this painting, I reflect on my professional life as a tree caring for others. As an immigrant arts therapist, I hope I have tried my best to care for others. At the beginning of my therapist career, my enthusiasm made me over-take from myself. Several times, I changed my timetable to fit my client’s needs, putting my family’s needs for my time and attention aside. Many times, I felt the urge to improve other’s lives quickly, regardless of their circumstances. I felt low when I could not see great improvements in my clients’ recovery journeys. Later on, when I finally established my own private practice with increasing numbers of referrals, there were several times when I felt the need to step away from my work and others’ emotions. At some moments, I found I was rushing in my sessions because of my fully booked schedule. I noticed I was thinking about my work sometimes during my days off. At those times, I did not realize that I was slipping into emotional burnout and compassion fatigue. Weiss (2004) identified four stages on the path to burnout for therapists: Enthusiasm, stagnation, frustration, and apathy (pp. 82–85). As a help-professional buried in a busy timetable, endless professional development trainings, and clinical meetings, I forgot to step down from the role of caring for others and to seek the shelter of being a human being cared for by others. My arts-making reminds me that a help-professional needs to be cared for because therapists are also human beings. Arts-making helps me step out of the cycle of the four stages of burnout and enables me to observe myself from a different perspective. Observing myself as a little person in a red cheongsam (Chinese traditional robe) standing under the acer tree, I imagine myself singing in wise poetic words like my ancestors (see Figure 8).

清風行雲思絮遙,聞香聽書塵念消。

內觀心冥至逐影,遠慾尋真自諧妙。

My thoughts drift away with the cleansing breeze and strolling clouds

The musk of incense and magic of ancient words banish stale and dusty thoughts

Meditation leaves me free to hear my heart, untroubled by stalking shadows

How wonderful to cast off wearying desire and discover true harmony inside

English translation of my Chinese poem, Ying (Ingrid) Wang (2021)

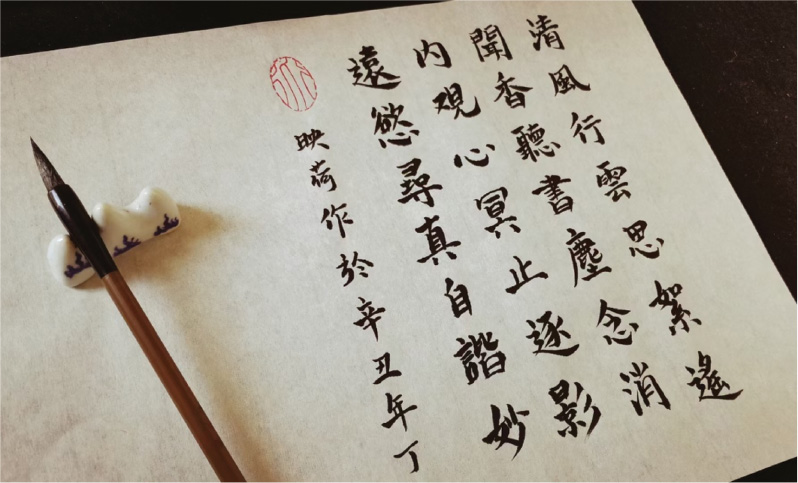

FIGURE 8 | My Chinese poem in ink.

Painting and poem are integrated in traditional Chinese landscape painting as “painting within poetry and poetry within painting” (Sui, 2019, p. 128). Bilman (2013) argues “poetry, like painting, is an art of inventive combinations” (p. 11); on the other hand, “painting is a marvelous language” through which to gain deeper understanding and insight into another culture (Rubinstein, 1999, p. 70). In Chinese classic-style poems, there are two kinds of beauty: rhythm and harmony—“one addressed to the eye, and one addressed to the ear” (Fenollosa & Pound, 2008, p. 138). In this poetic exploration, I use my first language to write a Chinese classic-style poem to capture my desire to connect with nature and harmony. I deepen my imagined sensations as the little person standing under the tree in the painting—to feel the breeze on my face, to see the strolling clouds, to smell the sandalwood incense, and to surrender my negative emotions from my compassion fatigue to my ancestors’ wisdom and guidance. Under the tree of my ancestral wisdom and spiritual support, I feel my heavy heart becoming lighter “untroubled by stalking shadows” of the fear from the harassing text. Under the tree of my ancestral wisdom and spiritual support, I push away all unnecessary desires around being an immigrant arts therapist but remember the importance of finding harmony in my heart.

I integrated the Chinese classic philosophical view of harmony 和 in my doctoral research into the immigrant therapist identity formation process. My arts-based doctoral research journey showed me a creative way to find harmony and rest in between my root culture and adopted culture and to find a place where 此心安处是吾家 [Home is where heart settles—from《定风波·南海归赠王定国侍人寓娘》] (Wang, 2021). When I observe myself under the acer tree in the painting and expand my embodied sensation through poetic imagination, I find this solid, strong, protective, and caring tree that can provide shade and a rest spot for me when I am tired, frustrated, or hurt from my professional life. This powerful and spiritual tree enables me to push away the unwanted high self-expectation, unhealthy self-doubts, and undesirable self-punishment. It empowers me to find balance and harmony between my own needs and my professional needs, to invite my heart to sit under my creative cultural tree, “and experience from a place of rest the inevitable comings and goings of emotions and events, the struggles and successes of the world” (Kornfield, 2008, p. 208).

Conclusion: Caring for Self, Caring for Others

In this paper, through autoethnographic narrative and arts-based inquiry, I showcase how a culturally relevant arts-making process helps me to process unhealthy and disruptive compassion fatigue as an immigrant arts therapist. Help-professionals often bury themselves under the hat of “expert” but forget the hat of “human.” Weiss relates a therapist’s self-care to the sharpening saw story in Stephen Covey’s book (1989), The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. Weiss (2004) reminds help-professionals to care for the self as if taking time “to sharpen the saw: physically, emotionally, socially, mentally and spiritually” (p. 73). Weiss (2004) says: “To be an effective and happy therapist, you need to keep your instrument, yourself, sharp at all times” (p. 74). To confront my compassion fatigue, I use culturally relevant arts-making to enable me to express my negative emotional distress safely. Through culturally relevant arts-making, I find transformational connection to my culture and homeland through creativity. In this arts-based intervention, I meet the enlightenment of finding my cultural and spiritual tree to support and care for myself as an immigrant arts therapist. This study highlights the importance for me as an immigrant therapist to continue arts-making as a life-long journey of knowing in research and professional practice.

In this research, through a decolonizing lens, I manifest the importance for the immigrant therapist to connect with their root culture, to use their first language, and to use their culturally relevant creative arts-making for self-reflection and self-care. As an immigrant therapist, my root culture connects me to the spiritual support from my ancestors. My root culture also guides me to see myself through my ancestral philosophical wisdom. As an immigrant arts therapist, I work with “something old” in my body, my memories and my emotions to “re-centre, re-claim and re-present” the wisdom and knowledge from my root culture as an academic approach (Smith, 2019, p. 13). This research argues that it is necessary for help-professionals with immigrant cultural backgrounds to explore their inner worlds through their deep cultural connections to their cultures, people and lands.

It is almost unavoidable to encounter compassion fatigue in the therapist’s professional life. As a helping professional, I have to learn how to care for myself through my arts and culture, in order to be able to continue opening my heart to care for others. In my professional career, I believe I will encounter more of this kind of challenge. However, as long as I continue to connect to the power of arts and cultural/spiritual support from my root culture through arts-making, I will always find the place to recover, to rest, and to grow. I hope my story of confronting my compassion fatigue and learning from my arts-making and root culture will encourage other help professionals to welcome these emotional distresses from their practice, and to meet personal and professional growth through their own arts, languages, and cultural/spiritual support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

About the Author

Ying (Ingrid) Wang is a post-doctoral research fellow at the Centre for Arts and Social Transformation, the University of Auckland. Her research interests include arts-based research in arts therapy, education, wellbeing and social transformation. She also has research experience in the public mental health sector and has been involved in a number of projects focusing on Asian communities' mental health in New Zealand. Ying also practices as a registered arts therapist specialising in displacement trauma, sexual trauma, depression, anxiety and other mental health issues. She is passionate about the power of creativity in both clinical practice and academic research.

References

Bilman, E. (2013). Modern ekphrasis. Peter Lang.

Covey, S. (1989). The 7 habits of highly effective people. Simon & Schuster.

Edgar, K. (1978). The epiphany of the self via poetry therapy. In A. Lerner (Ed.), Poetry in the therapeutic experience. Pergamon.

Fenollosa, E., & Pound, E. (2008). The Chinese written character as a medium for poetry: A critical edition. Fordham University Press.

Figley, C. R. (2002). Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self care. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(11), 1433–1441.

Green, D., Pears-Scown, N., Weir, M., Csata, I., Heney, R., McGeever, M., Wang, Y., Lambert, R., & Marks, K. (2018). The arts of making sense. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Arts Therapy, 12(1), 112–130.

Greenspan, B. (1999). A garden of opportunities: Personal writing for therapists. The Perspective: A Professional Journal of the Renfrew Foundation, 5(1), 4–6.

Kornfield, J. (2008). After the ecstasy, the laundry. Ebury Publishing.

Kottler, J. (1989). On being a therapist. Jossey-Bass.

McNiff, S. (1992). Art as medicine. Shambhala.

Perry, B. (2008). Why exemplary oncology nurses seem to avoid compassion fatigue. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal, 18(2), 87–92.

Progoff, I. (1992). At a journal workshop: The basic text and guide for using the intensive journal process. Dialogue House Library.

Rubinstein, L. (1999, spring). The great art of China’s ‘soundless poems’. Fidelio, 42–70.

Smith, H. (2019). Whatuora: theorizing “new” Indigenous methodology from “old” indigenous weaving practice. Art/Research International: A Transdisciplinary Journal, 4(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.18432/ari29393.

Stamm, B. H. (2002). Measuring compassion satisfaction as well as fatigue: Developmental history of the compassion fatigue and satisfaction test. In: C. R. Figley (Ed.), Treating compassion fatigue (pp. 107–119). Brunner Mazel.

Sui, G. (2019). Reverse ekphrasis: Teaching poetry-inspired Chinese brush painting workshops [in English]. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 38(1), 125–136. https://doi-org.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/10.1111/jade.12180.

Sussman, M. B. (1995). A perilous calling: The hazards of psychotherapy practice. John Wiley & Sons.

Todaro-Franceschi, V. (2012). Compassion fatigue and burnout in nursing: Enhancing professional 1uality of life. Springer Publishing Company.

Wang, Y. (2020). Poet tree. In F. Losefo, S. Holman Jones, & A. Harries (Eds.), Wayfinding and critical autoethnography (pp. 196–213). Routledge.

Wang, Y. (2021). Re-membering identity: A critical autoethnography through arts-based inquiry into being a New Zealand Chinese therapist. Doctoral thesis, The University of Auckland, University of Auckland Research Space. Retrieved June 08, 2022, from https://hdl.handle.net/2292/57862.

Weiss, L. (2004). Therapist’s guide to self-care. Taylor & Francis Group.

Wicks, R. J. (2007). The resilient clinician. Oxford University.