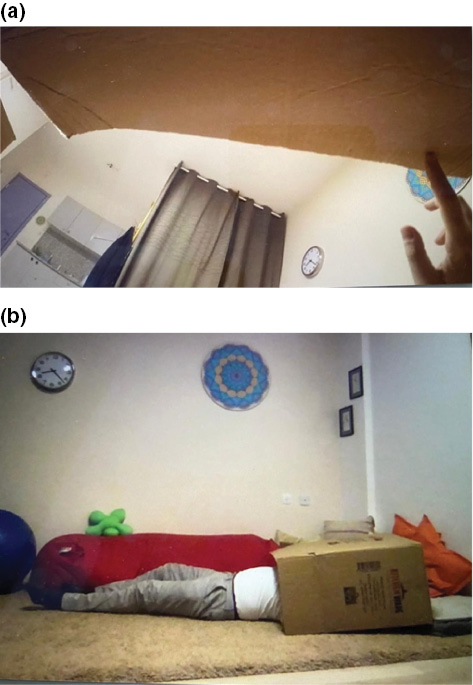

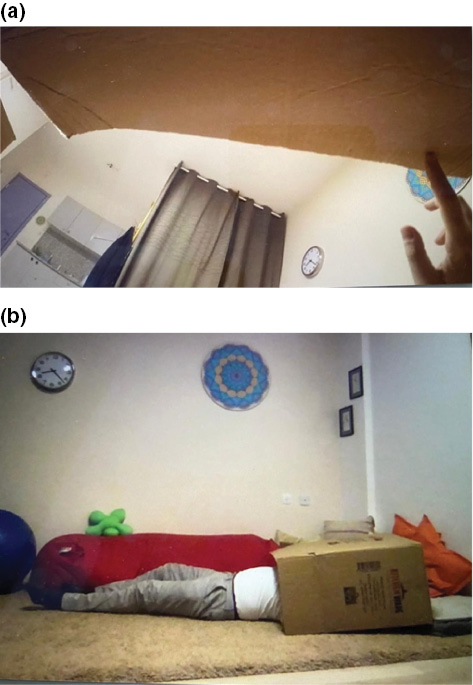

FIGURE 1 | Shot from the (a) GoPro camera and (b) from the side.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2022) 8(2):185–199 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2022/8/3 |

The Experience of Social Rejection: Developmental Transformations and a Multimodal Art Response Model as Applied to Art-based Research

社会拒绝的经验:发展性转化与多元艺术回应模型在基于艺术之研究的应用

1Herzog College, Israel

2Tel Hai Academic College, Israel

Abstract

In this preliminary study, we propose an expressive and interactive research method using a developmental transformations (DvT) model and a multimodal art response as applied to an art-based research (ABR) design, specifically relating to the experience of social rejection. We explored three research questions: Can the experience of social rejection be understood through playful interactions in DvT play? How does playing with the experience of rejection vary in solo play, play with an object, and play with a partner—i.e., otherness? How do researchers’ responses to participants enrich this understanding? This study delineates subjective and expressive ways of understanding the lived experience of social rejection through a multimodal approach, the DvT theory, and practice in an ABR design. Four DvT practitioners participated in a three-session pilot study, exploring rejection on their own and in pairs, then shared their experiences in a group discussion. Between sessions, the researchers shared their response films and visual response art with the participants. The outcomes of the study suggest that the experience of social rejection impacts both individual and partnered play, although its intensity seems to increase in pair interaction, and that response art supports participants’ exploration of this experience. Our research outcomes emphasized the need for expressive and interactive research methods, such as the application of DvT in ABR, in the study of complex and intersubjective social phenomena such as the experience of social rejection.

Keywords: social rejection, developmental transformations, art-based research, response art, GoPro in research

摘要

在这项初步研究中,我们使用发展性转化 (DvT) 模型和多元艺术回应模型,提出并采用了一种表达性与互动性的研究方法,应用于基于艺术之研究(ABR)设计,特别涉及社会拒绝的经验。我们要探索的三个研究问题如下:社会拒绝的经验能否通过 DvT 玩耍,在玩耍性互动的情境下被理解?把个人的经验投射到一个客体上,独自与被拒绝的经验玩耍与和一个伙伴玩耍被拒绝的经验有什么不同--即差异性?研究人员给予参与者回应的回应性取向是如何丰富这种理解的?这项试点研究通过多元模式取向、发展性转化 (DvT) 理论和实践基于艺术之研究 (ABR) 设计,阐明了以主观性和表达性的方式理解社会拒绝的生活经验。四位发展性转化 (DvT) 的实践者参加了一个三节的试点研究。他们最初自己探索被拒绝的经验,随后两人一组,最后在小组讨论中分享他们的经验。在几节之间,研究人员与参与者分享了他们的回应影片和视觉回应艺术。研究结果表明,社会拒绝的经验对独自玩耍和双人玩耍都产生影响,尽管其强度似乎在双人互动中有所增加;参与者在探索社会拒绝时分享了孤立、孤独、安全和缺乏安全、攻击和失望的强烈情绪,而回应艺术似乎支持了参与者对这些经验的探索。我们的研究结果强调,在研究复杂的、主体间的社会现象如社会拒绝的经验时,需要表达性和互动性的研究方法,如发展性转化 (DvT) 在基于艺术之研究 (ABR) 中的应用。

关键词:社会拒绝, 发展性转化, 基于艺术之研究, 回应艺术, 研究中的运动相机 (GoPro)

The Application of the Developmental Transformations Theory and Practice to the Study of Social Rejection

As humans, we differentiate between preferred and no preferred objects, people, and situations. We tend to draw closer to the preferred and distance ourselves from the unpreferred on a moment-to-moment basis (Johnson & Pitre, 2020). Rejection is therefore a primal and natural action that informs the choices we make. The experience of social rejection is an affective reaction to real, anticipated, remembered, or imagined rejection by other people, and evokes a variety of difficult emotional responses (Leary, 2015; Bondü & Krahé, 2015).

In recent years, social justice-oriented actions stemming from socially rejected communities and psychotherapy practice and research have highlighted the ethical response/ability to disrupt dynamics of social oppression and promote diversity and healing within a therapeutic framework (Sajnani, 2012; Sajnani et al., 2017). In particular, developmental transformations (DvT) has changed its orientation and currently gravitates toward a social justice perspective (Johnson & Sajnani, 2015; Johnson & Pitre, 2020). Our goal in this research was to incorporate DvT practice into an arts-based research design in order to study the experience of social rejection.

DvT is an arts-based performative practice (Johnson, 2020) that aims to decrease anxiety and enable adjustment to the unstable and ever-changing world we live in. The DvT model originated in the early 1980s from the combined clinical practice of drama therapy and dance and movement therapy (Johnson, 1993). It is an unstructured-improvisation model that takes place within the therapeutic containment of the playspace. The therapist and the client practice the continuous transformation of embodied encounters (Johnson, 2009). The playspace in DvT contains the therapeutic action, while the DvT therapist performs a double role: maintaining conducive conditions for play and playfully engaging with the client in the playspace (Galway, Hurd, & Johnson, 2004).

According to DvT theory, the moment-to-moment differences we perceive in our bodies, our interactions with others, and in our environment comprise one major reason for instability (Sajnani et al., 2017). In perceiving differences, we form a preference for one group, person, or object over another; the preferred is perceived as better, safer, or more attractive, whereas the other is oppressed or rejected. Through physical and emotional signals, the preferred elements approach intimacy, whereas the rejected elements are pushed away, contained, or controlled (Mayor, 2018).

By adhering to the conditions of the playspace—restraint against harm, mutual agreement to play, discrepant communication, and reversibility of roles and status (Johnson, 2009; Johnson & Pitre, 2020)—the therapist and client/s are able to explore themes of preference and rejection within the playspace. In addition, Dintino, Steiner, Smith, and Carlucci Galway (2015) claim that in order foreplay to be truly satisfying, it must be meaningful and salient (that is, perceived as preferred) (p. 23). For many clinical populations, the experience of social rejection might be experienced as a prevalent issue and therefore potentially salient.

DvT and the Other/Otherness/Othering

In DvT, the other and our proximity to the other are perceived as potential sources of turbulence and instability. Johnson (2013) suggests that without flexibility, resilience, or tolerance in the boundary region between oneself and others, one is left only with the choice of conflict or isolation, fight or flight. He states further that trust in others must be based on an embrace of their freedom, not in its restriction. DvT practice can be seen as a series of imperfect attempts by participants to be in proximity with one another without controlling the other (Mayor, 2018).

DvT practice does not attempt to do away with the experience of otherness, but rather calls attention to it as it arises in the playspace. DvT informed by social justice interrupts the dynamics that perpetuate harmful othering and promotes diversity as necessary to health and wellbeing (Sajnani et al., 2017).

Our research set out to investigate the experience of social rejection associated with otherness. What happens when we play with our experience of social rejection? How do playful encounters in the DvT playspace change our reactions to rejection or otherness? We propose that social rejection is inherent to our lived experience as human beings. Thus, the experience of social rejection is universal and manifests in different ways across all cultures and traditions.

Using Response Art in Research

Art has been used to explore clinical issues for many years (Fish, 2012). Response art may help to process professional issues and complex responses to therapeutic work (Fish, 2012; Malchiodi & Riley, 1996; Robbins, 1988; Wadeson, Marano-Geiser, & Ramsayer, 1990; Wadeson, 2003). Donald Winnicott described his “Squiggle Game” as a way of eliciting drawings from his young patients as early as 1958. The game involved an exchange of squiggle drawings as a form of “art conversation” between Winnicott and his pediatric patients (Berger, 1980).

The use of response art in art-based research (ABR) builds on the concept of the art conversation by incorporating art created by the researcher in response to the participants’ art. Fish (2008) used images created by therapists in order to gain a better understanding of their clients’ process and art; on occasion, these images were shared with the clients themselves.

Response art allows the researcher and the participants to communicate about their varied life experiences (Fish, 2008, 2012; Kapitan, Litell, & Torres, 2011; Van Lith, 2014; Wadeson, 2011). Through response art, researchers can express their understanding of the participants’ experiences without preconceived notions or judgments (Moon, 2009; Johnson et al., 2009). Cooper and Allen (1999), who used their own images and writing in their ABR, argue that response art allows researchers to uncover another layer of “truth” in their findings. McNiff reported in his 2007 study that response art helped the researcher to focus more on the artistic process than on the human subject, which contributed to the objectivity of the research. Havsteen-Franklin and Altamirano (2015) assert that responsive art making is a powerful tool because it establishes crucial forms of communication when words are not available.

The Multimodal Approach

In the literary and media arts, human experience is transmitted through the use of words (Ryan, 2014). As creative writing can unearth our thoughts and feelings with regard to a past that has yet to be revealed (Seih, Chung, & Pennebaker, 2011), it is not surprising that creative writing can be used effectively in multimodal research. Creative writing gives individuals living with hardships an opportunity to express their experiences (Bruera, Willey, Cohen, & Palmer, 2008; Henry et al., 2010).

When we view video footage of ourselves in action, we are able to take a different view of our experience, which in turn has the potential to enhance our understanding of a given condition (Barone, 2003). Hearing, seeing, and feeling lived experience through film not only helps the experience come to life, but enables connection to others with similar experiences (Weber, 2008). The transformation of research data into film or vice versa has been the subject of numerous studies (Eisner, 2006; Fish, 2017; Pink, 2001a,b; Sparkes, Nilges, Swan, & Dowling, 2003) and has been used in art therapy for almost fifty years (Carlton, 2014; Fryrear & Corbit, 1992; Malchiodi, 2000; McLeod, 1999; McNiff, 1981; McNiff & Cook, 1975). Malchiodi (2011), Leavy (2015), and Winther (2018) show the power of film to facilitate communication between researchers and participants.

In addition, the visual modality may lead viewers to emphasize, feel, imagine, and recognize the human condition (Sayre, 2001). The use of film is another way to represent reality as participants see it; much like other art modalities, it can enable different ways of making meanings of participants’ experiences (Winther, 2018). Still, it should be noted that the use of film as an art medium is not a more “truthful” or “objective” method than any of the other approaches (Buckingham, Pini, & Willett, 2009). Films and images are created and viewed through the values and experiences brought by the filmmaker and the viewer, and they often represent multiple layers of interpretation and bias.

Methodology/Research Design

Our research addressed the following questions: (a) Can we understand the experience of social rejection in playful interactions through DvT play? (b) How does playing with the experience of rejection vary in solo play, play with an object, and play with a partner? (c) How do researchers’ responses enrich this understanding? Our aim was to allow participants to examine their encounters with rejection in DvT play through creative writing and DvT play, as well as our own response art, and to explore ways to cope with rejection through DvT play.

This study involved four participants, each of whom participated in three sessions (Table 1). The first session, labeled session 1, was comprised of individual play. The second session, labeled session 2, involved duo/pair play. The third, labeled session 3, was a collective review session with all four co-players/researchers. In two additional sessions, the researchers worked on their own artistic responses without the participants present. The first response is labeled as Researcher’s Art-Response: Edited Film 1, and the second as Researcher’s Art-Response: Edited Film 2.

TABLE 1 | Example of Labeling System for All Materials for Fictitious Participant X

| Session | Labeled materials |

|---|---|

| Session 1 | X Creative writing 1 |

| X DvT play 1 | |

| Response Art | X Video session 1 |

| X Researcher’s video response 1 | |

| Session 2 | X Creative writing 2 |

| X DvT pair play 2 | |

| X Video session 2 | |

| Response Art | X Researcher’s video response 2 |

| Session 4 | X Video session 3 |

| Response Art | X Researcher’s art response 3 |

First Session: Creative Writing and Box Play

In the first session, the participants were invited to a studio with only a box inside the playspace. They were offered pen and paper and asked to think of a situation where they felt rejection, writing down their reflections in free verse or prose. The participant then played with the box while the main researchers watched from the witnessing circle within the playspace. Participants could choose to engage in dialogue, sharing observations and feelings while they worked, or create in silence. Sessions lasted from twenty to thirty minutes. The main researcher indicated the end of the session by telling the player: “Take a minute.” The participant was then given five minutes alone in the space for self-reflection.

The sessions were filmed in their entirety by a video camera in the corner of the room and by a GoPro camera attached to the participant’s forehead.

Second Session: Creative Writing and Pair Play

In the second session, participants were divided into pairs. Each pair was invited back to the studio, where, at the beginning of the session, they separately watched the video that had been created in response to their individual session. They were once again asked to respond to the video in writing.

Researcher’s Response Art: Edited Film 2

This session was conducted by the two main researchers; participants were not present. The researchers analyzed video footage from the two sessions in an attempt to interpret the participants’ words and motions. They noted hand gestures, movements in the space, interactions, and so on; they also recorded a precise transcript of all comments made by the participant during the creation process of texts and the DvT play session.

Third Session: Viewing and Processing Response Art

In the third and final session, the participants were invited as a group to view each of their edited films. They were then asked to respond orally to the film.

The participants were asked the following questions:

The Researcher’s Response Art

In the fourth and final session, during which the participants were not present, the researchers created a concluding work of visual response art. This work summarized the sessions as we experienced them and attempted to capture the role of each participant in the process, focusing on the image that we wanted to share with them.

Examination of Materials from the Sessions

Creative writing. The texts from creative writing 1 and 2 for each participant were examined. Noted were (a) issues raised, (b) the style and length of the writing, (c) the participant’s body language while writing, (d) connections between the writing and the filmed material from that session, and (e) significant changes between the writing in different sessions.

Video footage. All video recordings of the creative writing, DvT play, and remarks in the third session were transcribed and reviewed. Visual cues such as body language, mood, tone of voice, and frequency of verbal communication were also considered. Close scrutiny was dedicated to the video footage of the final discussions of Session 3, because this footage included the participants’ insights into the process and the effects of the inquiry. We then added our own reflections and conclusions, discussing any new knowledge that might have been gained from the inquiry.

Recruitment. Adults between the ages of 20 and 40 years were recruited from among trainees of the Israeli DvT Institute. All participants were drama therapists and level 2DvT practitioners. Candidates for selection were shown the detailed research design. At the end of this process, four volunteers were selected for the study: three women and one man with DvT training, all in their thirties or forties. All methods and goals of the study were clearly explained to the volunteers. They were informed that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time and that copies of the videos made from the sessions would be available to them after the study was completed. These terms and conditions were stated in writing in the preliminary consent form signed by each participant.

Results

Outcome 1: The Experience of Rejection in DvT

Outcome 1 can be summarized as follows: Playing with oneself as compared with playing with a partner, or playing with the other as object versus playing with the other as person.

The study involved two different sessions—the first alone, playing with a box, and the second playing with a partner—in order to examine the experience of rejection in both cases.

In the third meeting, participants compared their experience of rejection when playing with a box as opposed to a partner. Some expressed surprise when they were directed to play with a box, although this was specifically mentioned in their initial orientation for the study. Some participants wondered about the logic behind introducing an inanimate object into the DvT playspace, as this was an unusual choice for a DvT session. All anticipated difficulty in playing with the box, but three of the four ultimately reported that they were more playful than expected. Three participants engaged in imaginary play with the box, treating it as though it were a fellow participant. The fourth participant felt frustration even before beginning the session due to the anticipated unresponsiveness of the box. During play, Pat forcefully flattened it and playfully yelled: “Hit me back, you annoying thing!”

The participants experienced either a sense of isolation or a sense of solitude in their playful interactions with the box. At first, Tami felt that she had been rejected by the researcher and left to play on her own with the box. Tami later withdrew and hid herself in the box, where she reported feeling more secure and calm after withdrawing from a confrontational discourse with the researcher. Jana said that the box felt like a sanctuary that she explored in her play.

All four were surprised by the personal themes that emerged from their play with the box as the researcher looked on from the witnessing circle. They explored the notion of visibility—seeing and being seen; solitude as opposed to isolation; embodied and mostly silent play as opposed to an emphasis on verbalization; and communication and play with the witnessing researcher.

Upon watching the artistic response—short video clips of their play—three of the four participants acknowledged the level of verbalization that took place during the sessions. The participants were either highly verbal or almost non-verbal, a dynamic that was apparent in their encounter with their partners. On the whole, verbalization served as a means to reject the other by controlling the situation, as noted in the second play session—whether in Tami’s hostile discourse with the silent researcher, or Uri’s rejection of Pat’s playful and embodied offerings. In contrast, embodied interactions between Tami and Jana seemed to establish an emotional bond between the two participants and included a delightful “stickiness”: a rowdy, proximally entangled two-minute-long play. The researchers’ silent witnessing stance seemed to create a distancing and even a rejecting experience for the participants.

Outcome 2: Playing Alone vs. Playing with the Other

Outcome 2 can be summarized as: Uncovering or revealing what we know about rejection in play (with an object and with the other).

The creative writing exercise on rejection prior to entering the playspace was intended to help the participants focus on the experience of rejection over a relatively short time. The themes explored in the exercise varied among the participants, but a sense of discomfort was palpable in all the participants’ voices as they read their anecdotes aloud.

A discussion of the participants’ learning experience during the third session revealed that the box in the first session had offered physical and metaphorical containment. The box was a place within the playspace where one could feel solitude and safety while experiencing rejection. Tami said, “If I hadn’t had the box, I would have continued to react aggressively toward the researcher in the witnessing circle. Being inside the box enabled me to contain those feelings.” Tami contemplated the alienating effect of the researcher’s Foucauldian gaze. Jana said, “Having this [box] was like having a place where I could hide, like a sanctuary.”

When comparing both experiences—playing with the box and playing with the other—some expressed disappointment. Pat said, “I was disappointed. I knew the box wasn’t going to play back and that I needed to be active. But when I saw that I needed to be active playing with you [speaking to Uri], I was expecting much more, and I felt rejected.”

A few of the participants talked about the roles they adopted in their play during both sessions. Jana defined it as taking the role of the aggressor as opposed to the retaliator. All of the participants appear to have played with these roles. Two of the four participants were actively aggressive toward the researcher or with their boxes, while the other two treated the box as the aggressor. This dynamic continued when the pairs came together for their joint session. Pat expressed that she was waiting for Uri to actively play with her; when he did not, her disappointment made her retreat and become passive. The responsive element between the participants during the second session was a key factor in this research.

Outcome 3: Impact of the Responsive Approach

Outcome 3 can be summarized as: The correspondence between the findings of the response film art and the participants’ experiences of response art as a mediator.

After watching the edited response films, the participants complained that the researchers had omitted important elements of their sessions. Interestingly, most of these elements did not occur, or at least not to the extent remembered by the participants. When participants watched themselves play in the films, two main feelings came up towards the video. Firstly, watching the video enabled the participants to make a connection between sessions as well as to their previous play, and allowed them to understand what the researchers viewed as significant in their play. Secondly, participants found it meaningful that the researchers had taken time to review and edit their sessions, devoting considerable thought to the three-minute clips.

The first video was filmed using a GoPro camera attached to the participants’ heads, while the other film was taken from the side (Figure 1). Participants reported that the GoPro enabled them to feel what it was like to play “firsthand.” As Uri said: “Now we know what happened in the box when I was playing inside.” This angle enables observers from the outside to feel that they are in the players’ heads—not looking at them but through them, savoring their experience in a more authentic way.

Uri Session 1: Shot from the GoPro camera

Uri Session 1: Shot from the side

FIGURE 1 | Shot from the (a) GoPro camera and (b) from the side.

However, some participants questioned the editorial choices made in the response films. They felt that they would have edited the films differently and were concerned that some elements might be missing.

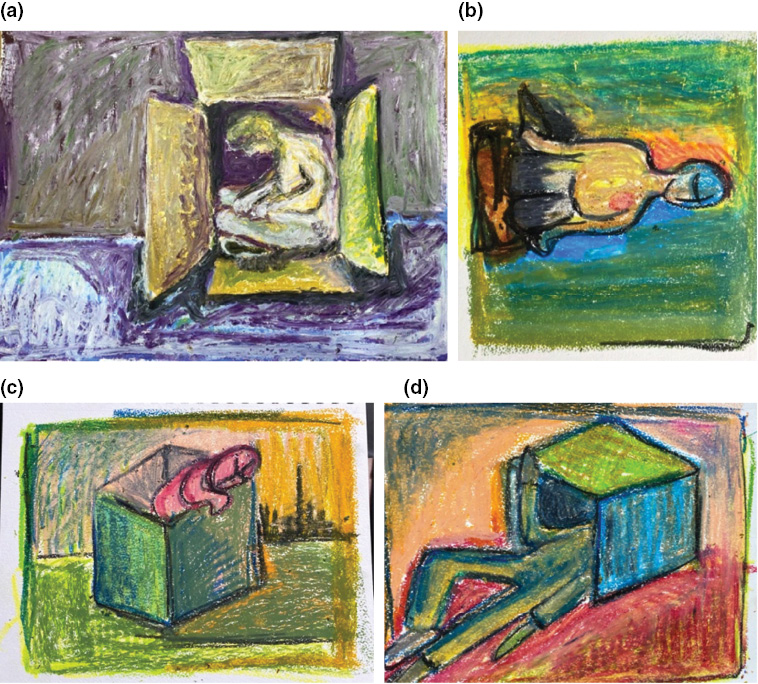

The researchers created a final art piece (Figure 2) in response to each of the participants’ processes. The participants were not present when this response art was created; they were later presented with the response art, along with the researchers’ notes.

FIGURE 2 | The visual response art to the processes of (a) Tami, (b) Pat, (c) Jana and (d) Uri.

When the participants shared their thoughts on this final response art, almost all of them discussed the sense of being seen. They were reminded of specific interactions or experiences during the process, so that the art served as an enhancement of their emotional experience.

Summary of Outcomes

Understanding the Experience of Rejection through Art

The creative writing aspect of the study helped participants to enter the playspace with a focus on experiences of rejection. It also allowed the researchers to better understand the “social rejections” with which the participants were willing to play. As the participants listened to themselves reading their writing in their final sessions, some were surprised by the things they had written and the level of intimacy they were willing to share. The writing seemed to be an effective catalyst for the introduction of the idea of social rejection into the play session.

The DvT play itself provided the participants with a safe space where they could experiment with their experiences of rejection. Play in the presence of a box allowed the participants to form a dialogue with the box. The box invited participants to play with social rejection on their own within a potentially containing or confining object. Surprisingly, they did not find it easier to play individually, serving in effect as their own objects, than to play with others. On the contrary, they attempted to engage with the main researchers in the witnessing circle. After the first session, they all said that they were looking forward to playing with their fellow participants.

The response art was shown to the participants sometime after their initial experience. According to some participants, it enabled them to recollect what they had experienced and to acknowledge the impact of these sessions. They noted the internal shift that had occurred as a result of the sessions, even if the shift “only” comprised heightened awareness of experiences of rejection in their lives.

Playing with Oneself vs. Playing with the Other

As noted above, the results indicated that the participants found it challenging to play alone, acting as objects in their own play. They felt that they had been rejected by the main researchers in the witnessing circle. Two of the participants acted aggressively in their play, while the other two were submissive. Still, the presence of the box in their play helped them to deal with their experience of rejection, as it provided a place of comfort and reassurance.

These power dynamics persisted in the second session, when the participants played in pairs. The participants who assumed the controlling role in the first session tried to play the same role vis-à-vis their counterparts. Although they had looked forward to play with others, some of them were disappointed. Some of their expectations for the session were not met, which led them once again to feel alone and rejected. However, the presence of a partner made it possible to play out these experiences in the relative safety of the playspace.

The Impact of Response Art

The videos allowed the participants to draw on their initial experiences as a starting point for the second and third sessions. They enabled the participants to connect to the experience of rejection and facilitated engagement with this theme.

When the participants looked at the three main outcomes, they explicitly acknowledged that they experienced rejection on a daily basis and that their participation in the research made them more aware of their personal approaches to with rejection. The participants appeared to differentiate between experiences of loneliness and isolation. During the third session, Pat said: “Participating in this research enhanced my perception. I now understand rejection with otherness better in relation to my experiences of loneliness.” Uri added: “I not only learned about my experiences of rejection with otherness, but also toward myself, the conflicts it brings up, and how much they relate to my experiences of rejection.”

Discussion

The study aimed to understand the experience of social rejection using a novel research design that applied DvT theory and practice to ABR. Human beings crave affection and closeness, and most of us find the experience of rejection challenging (Mayor, 2018). However, rejection is embedded in society; by living with others around us—that is, living with otherness—we risk rejection. DvT theory acknowledges that by showing preference to some, we oppress or reject others by default.

In this study, DvT provided an effective platform to examine social rejection and the complex emotional reaction it elicits. By keeping to the conditions of the playspace in this study—restraint against harm, maintaining mutuality, discrepancy, and reversibility (Johnson, 2009, 2013)—we were able to invite the participants to enter a safe enough playspace to explore the salient theme of rejection (Dintino et al., 2015).

The placement of a box in the DvT playspace enabled the participants to experience a container within a container—the box within the playspace. While the playspace allowed for representational, imaginary, and intersubjective encounters (Johnson, 1998), the box allowed the participants to play with their vulnerability in the absence of a “real other.” In it, they were their own objects, as the box reflected the otherness in their play.

The four research participants actively engaged in their experiences of social rejection: first through creative writing, then through individual play, and finally with a partner within the DvT playspace. This latter enabled them to play with their otherness side by side, each holding his or her own experience of rejection and at the same time engaging in playful dialogue with the other’s respective experience. The dialogue was held not only with their partners in play, but also with the main researchers, who witnessed two sessions and responded to them in film and visual art.

The study’s research design, which incorporated multimodal and art-based models, is consistent with the growing body of evidence indicating that the multimodal approach provides an opportunity for expression through visual art and embodied play of complex experiences such as social rejection (Bruera et al., 2008; Henry et al., 2010).

The results of the study demonstrate that artistic dialogue allowed the researchers to better understand the participants’ experience of rejection. When the researchers reflected their insights to the participants through artistic expression, the participants were better able to process their own experiences.

This is a preliminary study and leaves room for future adjustments. For example, the feedback given by the participants to the researchers’ film response may indicate that this aspect of the study was less successful. We are considering enhancing or replacing the film response with an improvised DvT response in future research; this may open up more opportunities for intersubjective dialogue.

In conclusion, the use of an interactive and expressive research approach involving DvT methods enabled the researchers to enter dialogue with the participants. It offered the inter/intrapersonal containment of the DvT playspace in order to explore the subjective and intersubjective experiences of social rejection expressed in play and in the subsequent discussion.

Limitations of Study and Future Research

The limitations mentioned here applied to the researchers and the participants alike. In this study, participants had considerable experience in DvT practice, because familiarity with the playspace is a necessary condition in applying this method. Therefore, the four participants were from similar academic and professional backgrounds. Future studies should examine the DvT model among a more diverse population.

Future research may explore experiences of social rejection and their manifestation in Eastern as well as additional Western cultures. This will potentially further our knowledge of the experience of social rejection in connection to specific cultures.

An arts-based, expressive, and intersubjective research model has the potential to alleviate social rejection experienced as the social exclusion of marginalized and underprivileged social groups. For example, the research of disabilities through a DvT-ABR approach has the potential to significantly advance interpersonal dialogue between groups.

Acknowledgement

There was no funding for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

About the Authors

Dina Fried, PhD is an arts therapist and DvT graduate. She is the director of the MA program in Arts Therapy at Herzog Academic College. She is a therapist and field expert in arts therapy at the Ministry of Education and develops academic programs in the fields of special education and art therapy. Her areas of research focus on art therapy, difficulties related to special education populations, ABR, and creative-based teaching-learning processes in higher education.

Gideon Zehavi, MA, RDT/BCT is a seasoned drama therapist, supervisor, and lecturer on drama therapy at Tel Hai Academic College. He has published several papers on the treatment of ASD-diagnosed children and adolescents, as well as on DvT and drama therapy-based autobiographical performances. Gideon is the founder and former director of the Israeli Institute for Developmental Transformation and the current training director of the DvT Institute in Shenzhen, China.

References

Barone, T. (2003). Challenging the educational imaginary: Issues of form, substance, and quality in film-based research. Qualitative Inquiry, 9(2), 202–217.

Berger, J. (1980). About looking. In Uses of photography (pp. 52–67). Pantheon Books.

Bondü, R., & Krahé, B. (2015). Links of justice and rejection sensitivity with aggression in childhood and adolescence. Aggressive Behavior, 41, 353–368.

Bruera, E., Willey, J., Cohen, M., & Palmer, J. L. (2008). Expressive writing in patients receiving palliative care: A feasibility study. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 11(1), 15–19.

Buckingham, D., Pini, M., & Willett, R. (2009). ‘Take back the tube!’: The discursive construction of amateur film- and video-making. In D. Buckingham & R. Willett (Eds.), Video cultures (pp. 51–70). Palgrave Macmillan.

Carlton, N. R. (2014). Digital media use in art therapy (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Database. (UMI No. 368214).

Cooper, P. J., & Allen, N. B. (1999). The quilters: Women and domestic art: An oral history. Texas Tech University Press.

Dintino, C., Steiner, N., Smith, A., & Carlucci Galway, K. (2015). Developmental Transformations and playing with the unplayable. Retrieved from http://www.developmentaltransformations.com/images/A_Chest_of_Broken_Toys-2.pdf. 9.11.21

Eisner, E. (2006). Does arts-based research have a future? Inaugural lecture for the first European conference on arts-based research, Belfast, Northern Ireland, June 2005. Studies in Art Education, 48(1), 9–18.

Fish, B. J. (2008). Formative evaluation research of art-based supervision in art therapy training. Art Therapy, 25(2), 70–77.

Fish, B. J. (2012). Response-art: The art of the art therapist. Art Therapy, 29(3), 138–143.

Fish, B. J. (2017). Art-based supervision: Cultivating therapeutic insight through imagery. New York, NY: Routledge.

Fryrear, J. L., & Corbit, I. E. (1992). Photo art therapy: A Jungian perspective. Charles C. Thomas.

Galway, K., Hurd, K., & Johnson, D. R. (2004). Developmental transformations in group therapy with homeless people with a mental illness. In D. Wiener & L. Oxford (Eds.), Action therapy with families and groups (pp. 135–162). APA.

Havsteen-Franklin, D., & Altamirano, J. C. (2015). Containing the uncontainable: Responsive art making in art therapy as a method to facilitate mentalization. International Journal of Art Therapy, 20(2), 54–65.

Henry, E. A., Schlegel, R. J., Talley, A. E., Molix, L. A., & Bettencourt, B. (2010, November). The feasibility and effectiveness of expressive writing for rural and urban breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum, 37(6), 749–757.

Johnson, D. R. (1993). Marian Chace’s influence on drama therapy. In S. Sandel, S. Chaiklin, & A. Lohn (Eds.), Foundations of dance/movement therapy. Columbia, MD: American Dance Therapy Association.

Johnson, D. R. (1998). On the therapeutic action of the creative arts therapies: The psychodynamic model. Arts in Psychotherapy, 25, 85–99.

Johnson, D. R. (2009). Developmental transformations: Towards the body as presence. In D. R. Johnson & R. Emunah (Eds.), Current approaches in drama therapy (2nd ed.), (pp. 89–116). Charles C. Thomas.

Johnson, D. R. (2013). Developmental transformations—Text for practitioners II. Institute for Developmental Transformations.

Johnson, D. R. & Pitre, R. (2020). Developmental transformations. In D. R. Johnson & R. Emunah (Eds.), Current approaches in drama therapy, 3rd ed. (pp. 121–161). Charles C. Thomas.

Johnson, D. R., & Sajnani, N. (2015). Convers are: Developmental transformations and social Justice. In A chest of broken toys: A journal of developmental transformations. Retrieved from http://www.developmentaltransformations.com/images/A_Chest_of_Broken_Toys-2.pdf. 9/11/21

Kapitan, L., Litell, M., & Torres, A. (2011). Creative art therapy in a community’s participatory research and social transformation. Art Therapy, 28(2), 64–73.

Leary, M. R. (2015). Emotional responses to interpersonal rejection. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 17(4), 435–441.

Leavy, P. (2015). Method meets art: Arts-based research practice (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Malchiodi, C. A. (2000). Art therapy and computer technology: A virtual studio of possibilities. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Malchiodi, C. A. (2011). Art therapy materials, media and methods. In C. A. Malchiodi (Ed.), Handbook of Art Therapy, 2nd ed. (p. 33). Guilford Press.

Malchiodi, C. A., & Riley, S. (1996). Supervision and related issues: A handbook for professionals. Magnolia Street Publishers.

Mayor, C. (2018). Political openings in developmental transformations: Performing an ambivalent love letter. Drama Therapy Review, 4(2), 233–247.

McLeod, J. (1999). Practitioner research in counselling. Sage.

McNiff, S. (1981). The arts and psychotherapy. Charles C. Thomas.

McNiff, S. (2007). Empathy with the shadow: Engaging and transforming difficulties through art. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 47(3), 392–399.

McNiff, S. A., & Cook, C. C. (1975). Video art therapy. Art Psychotherapy, 2(1), 55–63.

Moon, B. L. (2009). Existential art therapy: The canvas mirror. Charles C. Thomas.

Pink, S. (2001a). Doing visual ethnography: Images, media and representation in research. Sage.

Pink, S. (2001b). More visualising, more methodologies: On video, reflexivity and qualitative research. The Sociological Review, 49(4), 586–599.

Robbins, A. (1988). Between therapists: The processing of transference/countertransference material. Human Sciences Press.

Ryan, M. (2014). Writers as performers: Developing reflexive and creative writing identities. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 13(3), 130–148.

Sajnani, N. (2012). Response/ability: Imagining a critical race feminist paradigm for the creative arts. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 39, 186–191.

Sajnani, N., Marxen, E., & Zarate, R. (2017). Critical perspectives in the arts therapies: Response/ability across a continuum of practice. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 54, 28–37.

Sayre, S. (2001). Qualitative methods for marketplace research. Sage.

Seih, Y. T., Chung, C. K., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2011). Experimental manipulations of perspective taking and perspective switching in expressive writing. Cognition & Emotion, 25(5), 926–938.

Sparkes, A. C., Nilges, L., Swan, P., & Dowling, F. (2003). Poetic representations in sport and physical education: Insider perspectives 1. Sport, Education and Society, 8(2), 153–177.

Van Lith, T. (2014). “Painting to find my spirit”: Art making as the vehicle to find meaning and connection in the mental health recovery process. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, 16(1), 19–36.

Wadeson, H. (2003). Making art for professional processing. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 20(4), 208–218.

Wadeson, H. (2011). Journaling cancer in words and images: Caught in the clutch of the crab. Charles C. Thomas.

Wadeson, H., Marano-Geiser, R., & Ramsayer, J. (1990). Through the looking glass III: Exploring the dark side through post session artwork. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 7(3), 114–118.

Weber, S. (2008). Visual images in research. In A. L. Cole & J. G. Knowles (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research (pp. 41–53). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Winther, H. (2018). Dancing days with young people: An art-based coproduced research film on embodied leadership, creativity, and innovative education. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1). https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1609406918789330