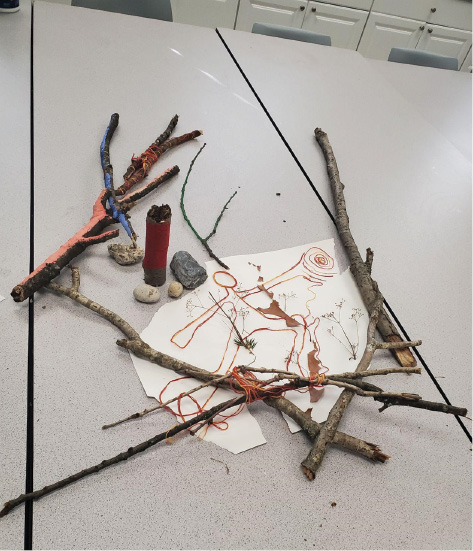

FIGURE 1 | Being with the unknown branches, paint, rock, papers, and string.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2022) 8(2):142–157 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2022/8/13 |

Making Nature Personal: Fostering Vulnerability, Compassion, and Personal Growth Through a Transpersonal Eco-Art Process

使个体融于自然:通过超个人生态艺术的探索过程提升脆弱、培养慈心,促进个人成长

1Caldwell University, USA

Abstract

As the Earth suffers from climate change, global warming, and its inhabitants’ irresponsibility, environmental activists suggest that Earth’s inhabitants must participate in social action to find greater consciousness and compassion for self and others in their relationships with the Earth. The authors engaged in five weekly sessions to use nature-assisted eco-art therapy to explore their individual processes. The themes that emerged included tension–control, submission–dominance, intimacy tolerance, compassion-observing emotions, and separation–retreat. These themes reflect what often develops in both the therapist–individual relationship and within the Earth’s inhabitants as self-regulating organisms.

Keywords: eco-art therapy, social action, transpersonal symbolism, eco-psychology, land arts

摘要

随着地球遭受气候变化、全球变暖以及地球居民环境失责,环境活动家建议地球居民必须参与社会行动,为自身和他人与地球相处扩展意识和慈心。作者们参加了五次每周一次的疗程,使用自然辅助的生态艺术治疗探索他们个人身处环境的过程。出现的主题包括:紧张-控制、顺从-支配、亲密关系容忍度、慈心-观察情绪以及分离-退缩。这些主题反映了在治疗师与个体来访的关系中,以及作为自我调节生命体的地球居民之间通常会出现的主题。

关键词: 生态艺术治疗, 社会行动, 超个人象征主义, 生态心理学, 大地艺术(地景艺术)

Introduction

Throughout the lifespan, there are unlimited opportunities to interact with multiple environments. In many cases, exploring the green outdoors may be a healthier alternative than the home environment. During turbulent times, being outside may be a safe haven or a place of contemplation. The ecosystem, planet Earth, in which all living entities exist, possess therapeutic qualities that provide health benefits and hold a space for contemplation and creativity (Davis, 1998). “Therapy environments are ecologies that produce particular conditions for creation. Environment is the here and now and what could be” (Whitaker, 2017, p. 1). In the here and now, reestablishing nature-based creativity as a primary source to turn when darkness looms demands an exploration of themes such as personal transformation and emotional growth (Whitaker, 2011).

As Kopytin (2020, 2021) described, eco-art therapy provides a subjective understanding of the therapeutic potential of creative and expressive processes to heal and develop relationships with each other and the living environment. The first author of this article visited Iceland and Oregon in 2021, exploring natural sites like volcanoes, geysers, and National Park Crater Lake. Within this vast beauty were moments of entering the spiritual realm and contemplation. However, forest fires had produced ashy trees, and hazy smoke lessened crater lake’s bright aquamarine blue.

Forest fires exemplify nature’s wrath against the carelessness of Earth’s inhabitants. Human acts of environmental perpetration, seen and unseen, may contribute to individualistic and collective trauma, often resulting in emotional numbing or increased defense mechanisms. Defense mechanisms can elicit power to lessen in tense negative emotions but reduce or diminish the capacity for positive emotions such as compassion. Compassion can be within one self throughout the lifespan, exemplified by pity and understanding that all living beings share suffering (Sang, 2021).

The first author joined a Unitarian Universalist (UU) community where individuals gathered weekly to address social action issues, including environmental justice. The community acknowledged nature’s sacredness and the duality of human and nonhuman entities. They linked between connecting with nature with its positive health outcomes and an appreciation of the nonhuman world (Richardson et al., 2019). Macy (1995) suggested that all connections to the Earth are intimate and ancient. By maintaining sustainable resources from the natural environment, the Earth’s inhabitants can reap positive rewards and develop reciprocal relationships with the planet.

This article’s authors are interested in an eco-art therapy. Summer, an art therapy professor at a New Jersey university, and Yermakov, an art therapy graduate student, met weekly for 5 weeks (January–February 2022) and engaged in nature-based eco-art.

Theoretical Framework

In this section, we summarize several perspectives and frame works addressed in the literature. Eco-art activism approaches provide greater context on how artists use the natural landscape to interact with the environment and explore self and space.

Jung and Ecology

The Jungian ecological perspective lends itself to transpersonal approaches to extend empathy, compassion, and personal transformation (Geha, 2019). Jung believed that a fully individuated person could actively participate in the natural world. He could foresee unlimited potential but felt people were the root of the world’s environmental and social problems and the greatest threat to themselves and the natural world (Yunt, 2001). Ryland (2000) echoed Jung’s beliefs, expressing concern about passive engagement with environmental consciousness—because people caused the environmental disrepair.

According to Jung, the collective unconscious contains the cultural and historical influences on one’s identity. The collective unconscious, moves toward a place of consciousness and interconnectedness where there is greater recognition of one’s symbols Universal symbols, archetypes, are emotionally charged images that emerge from complexes, which are bundles of energy. When sparked by psychic energy, complexes influence the conscious mind. The collective unconscious and archetypes are universal; they elicit subjective, cross-cultural meanings and become part of one’s tacit knowledge (Swan-Foster, 2016).

Transpersonal Framework

Transpersonal approaches focus on overall health and well-being. They use contemplative practices that allow greater intentionality, compassion, and flow (Vespa et al., 2018). Images that emerge amid such practices originate from the inner consciousness when engaged in the creative process (Franklin, 2001). Images have the capacity to bring the reality of a current crisis, and universality of an individual’s suffering (Hocoy, 2005). Jung (1961, as cited by Hocoy, 2005) noted, “The images of the unconscious place a great responsibility upon a man. Failure to understand them, or a shirking of ethical responsibility, deprives him of his wholeness and imposes a painful fragmentariness on his life” (p. 193). Jung argued that if individuals cannot be accountable for recognizing meaning or symbols, the shadow side or unwanted/repressed side may contribute to irresponsible action toward the planet (Hocoy, 2005). Ultimately, social action depends on the relationships between personal and collective suffering.

Transpersonal eco-art therapy allows individuals to explore personal symbols representing perceptual, emotional, and spiritual experiences (Pike, 2021). Moving across eight nonlinear levels of consciousness may help individuals connect to a greater awareness (Kossak, 2009, as cited by Geha, 2019; Pike, 2021) and understand their place in the physical world. The authors integrated parts of these levels into their 5-week process:

Existential eco-art therapy offers individuals the possibility to explore anxiety or instability by being in the present while working with natural materials. A’court (2021) suggested remaining in a silent space while making art. The recognition of nondualism in one’s circumstances can be explored through an “inter-relational space, in dynamic relationship with the surrounding ecology” (p. 24). With greater mindfulness and consciousness, more feelings emerge. These emotions may hasten the urgency of repairing oneself and lessen existential angst (Macy, 2007). From an East–West perspective, existential eco-art therapy has the potential to change perceptions. People could perceive their experiences as part of the larger human experience rather than separate and isolating and hold their painful thoughts and feelings in balance rather than over identify with them (Chung, 2018).

Ecopsychology

Ecopsychology is described as a radical paradigm consisting of a systems approach and multiple perspectives from the field of psychology. Suggesting that humans are connected unconsciously to all life on Earth, ecopsychology consists of active engagement in psychotherapeutic activities to increase ecological consciousness. It addresses sources of violence to human and more-than-human nature that contributed to our ecopsychological crisis’s historical, cultural, and political roots (Fisher, 2013). Roszak (1992) believed that ecopsychology provided a more-restorative perspective with the hope of understanding the dismay of industrial growth and irresponsible human behaviors and working to achieve a sustainable planet. There is no clear definition of ecopsychology. Snell, Simmonds, and Webster (2011, noted that it “remains a loosely defined area that overlaps significantly with other environmentally focused psychologies; there is a potential risk that ecopsychology may lose sight of what makes it unique and become disenfranchised by related areas of scholarship” (p. 106).

Nature Therapy

Nature therapy follows the same assumptions as ecopsychology: By reconnecting with nature, people can connect to their strengths and achieve greater wellness (Hinds, 2011). Nature therapy takes place in nature and uses creative methods with nature as a partner in the process (Berger & McLeod, 2006). Its proponents claim that postmodern life reduced the individual’s ability to connect with others, the environment, and parts within (Berger, 2009). Those “parts within” may refer to the self that contributed to unethical or irresponsible actions and detrimentally affected the natural world. By engaging in nature therapy, individuals might achieve a greater sense of integration.

Environmental Art Movements and Activism

For centuries, artists have depicted nature in romanticized views and images of harmonious connections between humans and nonhumans. Levine (2020) noted an aesthetic responsibility to shape the world to create a sensory-oriented space where forms can emerge and change landscapes. Nash (2021) echoed Levine, adding that social engagement through the arts in natural environments could raise eco-awareness of, for example, the climate crisis. Following are example artists and artistic movements related to environmental arts activism.

Believing the best sites for Earth art are reckless urbanization or nature’s destruction, Robert Smithson sought out sites for his work that industry had damaged or disrupted (Delaney, 2008). His most notable piece is The Spiral Jetty.

Also called the earth art movement or earthworks, the land art movement refers to art that blends and relates to its environment. Many works were made from materials located at or near the sites. The land art movement deals with questions of natural versus artificial and whether they can be separated. Andy Goldsworthy, an artist from this movement, use dephemeral materials such as leaves, branches, and twigs that disintegrate and return to nature (Alt, 2021).

The forest school encompasses early outdoor education, with all children spending time in forest or woodland settings. Examples of activities include climbing trees, building dens and shelters, engaging in imaginative and fantasy play such as storytelling, and using full-size tools to cut, carve, and create from natural materials. This psycho educational tool teaches youth to respect nature and develop positive health outcomes (Leather & Nicholls, 2016).

Sprinkle and Stephens (2021) defined ecosexual as a “person who imagines sex as an ecology that extends beyond the physical body” (p. 43). They acknowledged their love for all lands and viewed eco sexuality as a “framework for understanding ourselves within the context of larger system” (p. 46). Their manifesto highlighted six pledges, including treating the Earth with kindness and engaging in art forms that resist damaging it further.

Setting the Natural Stage

We met for a 5-week eco-art-based inquiry experience to examine personal symbols through an emerging process and written reflections (Whitaker, 2011). Because of inclement weather, we held most sessions indoors for an hour. However, on the same day as sessions, we gathered natural materials—branches, leaves, pinecones, acorns, fallen leaves, and discarded or decayed tree debris—from the university grounds. The selection was equitable based on the available materials’ textures, shapes, and variety. Although the experience of creating outside may have produced different sensory and kinesthetic experiences, using the classroom as a contained laboratory contributed to the immersive process (Whitaker, 2017).

The sessions had moments of contemplation but no predetermination of what would emerge. We immersed ourselves in a process that was silent despite each other’s presence and in moments of collaborating with the materials. Several hours after making our art, we wrote our reflections on it. In the next section, we highlight significant images, themes, and individual reflections on the process.

Week 1: Tension–Control

Summer: I chose several branches from outside, intending to challenge my resistance to sculpture, and bound together several tree limbs with string. The repetition of wrapping and heightening and easing the tension was calming. The experience explored an internal tension as I played with the duality of what is oftens to red in the body: tension and release. One must manage frustration with tolerance and patience to work with unconventional materials. Although the work felt unsettling, there was stability in piecing it together. One branch reminded me of as word or dagger, and I was in awe by this symbol of power.

When we put our images together, the 2D and 3D elements created a story that was not clearly defined but suggested possibilities (Figure 1). As new symbols emerged, I put less pressure on myself to make the art look a particular way. The tension I originally carried began to ease, but another emerged: power or disempower. Were these tensions enacted in different roles in my life? In light of this tension, I was struck by the peace and relaxation I felt in completing the work. I learned that it is okay to feel and ultimately become free of emotions in the act of creativity. Filling up with emotions also creates feelings of vulnerability.

FIGURE 1 | Being with the unknown branches, paint, rock, papers, and string.

Yermakov: The responsibility to live up to expectations held hands with playfulness. The sticks I picked up reminded me of little trees, and the warm feeling of playfulness overshadowed my uncertainty. Dr. Summer’s materials felt rigid, as though they were angry. I felt intimidated, terrified. That weight fell from my shoulders when I verbalized the materials’ intensity after the session (Figure 2). As I started to work with the tiny branches, leaves, and pine needles, I noticed nature’s fragility and connected it with the fragility within me that is transferred through art. The elements I chose forced me to pay attention to the present—because every moment mattered, considering the materials’ delicate nature. My final art product showed my own emotions at that moment; they were hard to dissect. With my need to be satisfied with the final product came the overwhelming fear that I could not validate or fully “see” my emotions.

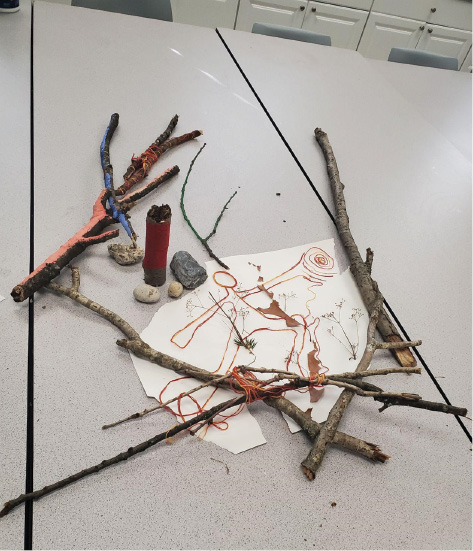

FIGURE 2 | Domination/submission: Leaves and branches on paper.

After Dr. Summer left the room, the aura changed to another therapeutic presence. Perhaps the relieving state I was in was unfamiliar, especially when I was not alone. Once we acknowledged the energy flow, we drifted away from needing to fill the space with words. There was an intimacy in being together with another person without words. I began to miss the pieces once I was away from the art project. There had been a comfort and almost-intimate connection between the work and a hidden part of me.

Week 2: Domination–Submission

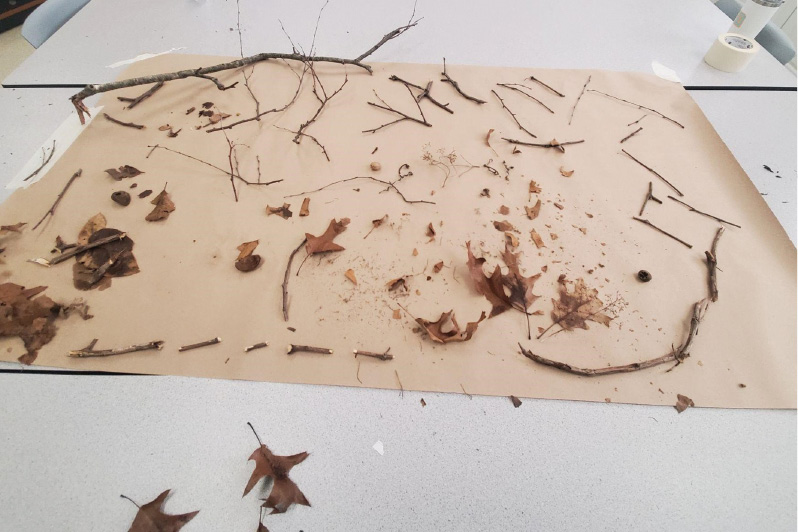

Summer: In addition to our individual projects, we collaborated on one piece indoors, creating a space where the materials were interchangeable. The materials’ unpredictability and resistance lessened this time. Perhaps there was greater comfort in working together and being in a place where we could collaborate. I initially felt agitation as I crumbled the specks and small leaves, creating a funnel effect on the paper and power in playing with natural materials, turning life into decay.

Upon selecting the branches, I noticed the twigs’ unusual shapes on the branches. They resembled small phallic objects battling for domination but submissive to the more-dominant snakelike branch. Archetypal symbols revealed a shadow side not often prominent. Instead, I often preferred passive engagement while my dominant side rages, and it is difficult to differentiate which will emerge victorious. The snakelike, phallic forms continued to battle. Which would dominate and emerge as a victor? Perhaps the delicate, calming sensation of crumbling leaves eased some of my tension. I saw that even when there is form, there is no form. Near the end of our time together, I noticed Brigitt and her work. We were together, separate, and then together again.

Yermakov: It felt almost forced to work with the natural materials. Within the classroom environment, they appeared awkward, minimal, a part of a separated whole, and forced into production. However, there was peace in creating something almost immature. Looking, touching, and maneuvering the leaves and sticks was meditative. I was drawn to the wet leaves’ submissiveness and the dry ones’ fragility and maneuverability. I noticed Dr. Summer’s presence but focused on the energy exchanged in the room. I felt submissive and partially protected. Dr. Summer was more expressive, taking up space in a way that felt intrinsic and meditative yet separate from mine. Despite our minimal collaboration, the image flowed in its own way.

The way we placed the branches seemed to serve as a holding space, a gateway that felt like a hug for the rest of the image. Upon reflection, we had a kind of collective unconscious at play; we both carried feelings of submissiveness and dominance (Figure 2). Creating eco-art appeared to balance our natural energy without language or thought. Accepting silence during creative expression eased bringing forth honest intention and quieting ego and judgment.

Week 3: Intimacy Tolerance

Summer: Ritual is part of a liminal process where symbols may lead to greater transformation; our weekly eco-art making became ritualistic. Their nascent images left me in a place of uncertainty or liminality (Green, 2021). We used wooden blocks and carved them with scissors. There was initial resistance, like carving into a body with no blood. The lines on the wood block offered a history not quite known but had a story and history of their own.

Working with an object from the Earth offered a sense of renewal and reintegration (Atkins & Snyder, 2017; Green, 2021). My resistance lessened, and the lines etching turned into trees. A knothole emerged, and I began turning it into an owl-like creature—wise, curious, and mysterious. I became more aware of what was happening in the here-and-now: togetherness, attachment, disruption, reconnection, sadness, loss, joy, and disconnection.

On the new piece of wood with which we would collaborate, I started carving a leaf. We worked to complete a nonbinary “Jesus figure” (Figure 3). The arms are outstretched, and the face is unformed, but we paid much attention to the chest and abdomen. We etched flowy lines to create greater depth and boldness. I felt connected to the wood; it represented transformation and interconnectedness (Della Cagnoletta et al., 2021). In this work, we could connect to theory—relational and psychoanalysis where there is witnessing, following the contact, and regression of the other. Feeling emotion was a practice of tolerance.

FIGURE 3 | Jesus: wood carving.

Yermakov: I was apprehensive about partaking in this week’s experiential. I was exhausted after a long weekend and thought I lacked the concentration to make purposeful art. These wood blocks were hard and definitive in shape, size, and composition—the opposite of how I felt. If I was to do art, I wanted to release energy—aggression, exhaustion, and blankness. I felt dissatisfaction in “hurting” the wood or going against its grain. I did not want to disrespect it; I had personified it as noble.

As I lessened my grip, the carving process became more harmonious. Still, I was not fully satisfied because it lacked contrast. I felt alone and perpetuating my negative outlook, so I asked to switch pieces with Dr. Summer. Switching blocks made me more comfortable; I envisioned life within the scenery. The project highlighted the relational process, pinpointing how resistances feel within me and with others and how to work through them with imagery.

Week 4: Compassion-Observing Emotions

Summer: Throughout the process, I had felt soul nourishment (Knill et al., 2005), a greater sense of aliveness and ecological consciousness (Rousseau & Deschacht, 2020). I became more open, taking time to see what was present and feeling compassion toward these once-living beings. The branches and veiny leaves created an image of lungs and an air sac. The materials, although separate entities, also had lived and breathed.

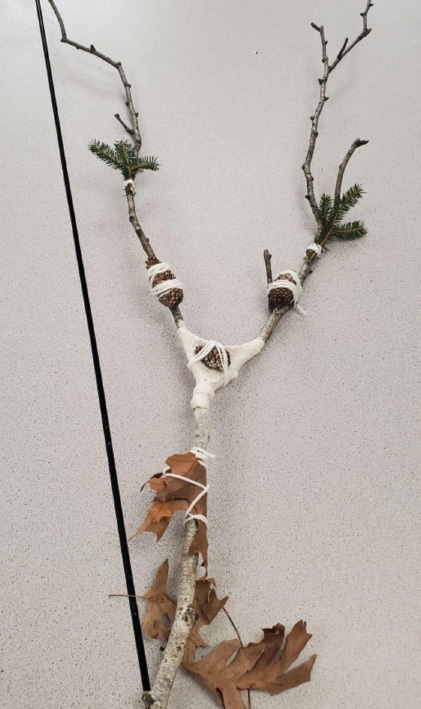

I began playing with the materials. As I deconstructed the original image, it no longer looked like a heart or lungs. I picked up two pinecones and positioned them, the first near the base of the bound sticks and wrapped it with string, mummifying it. I wedged the second, partially wrapped, between the two branches, and bound and tightly wrapped the bottom of the sculpture. While the remaining branches and leaves provided cover, one pinecone watched over the other like a sleeping baby (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4 | Mummified pinecone.

As I reflected on my piece, the themes of protection, stability, safety, comfort, bravery, and stalwartness arose. The base’s tightly wound restriction could symbolize the struggle to break free from anxiety. There is greater freedom outside, where one can breathe and be with the Earth.

Yermakov: Throughout the session, an image that resonated was a deer, an innocent species that humans intrude upon and abuse. It brought home how eco-art therapy had grown my awareness of self, relations, and the environment. The deer’s head received more attention than its body (Figure 5). I had thus far used my head and thoughts to guide and console myself.

FIGURE 5 | Baby deer: branches, leaves, string, and plaster strips.

Dr. Summer’s and my pieces carried similar messages of hidden parts and concentrated on aspects of the objects at hand. We both seemed to seek ways to visualize the compartments of what we identified with, what we needed to work on, and who we were. Reflection was integral to the process after feeling the emotions first. It allowed thought about how such unfamiliar objects and experiences translated to ourselves—bringing physical objects in from the environment allowed distance, whereas the object’s invitation led the emotions. There was no need to alter, but rather observe, the emotions along the process. When creating with eco or easily malleable materials, there was less distance and more rawness and activation, which could be overwhelming.

Week 5: Separation–Retreat

Summer: We held our last meeting outside and chose a combination of natural and conventional art materials from which I felt resistance. I peeled the bark from a stick. The peeling felt symbolic—skinning, digging, scratching, clawing, getting deeper into understanding emotions, and being in the moment. I stripped a few layers and discarded them; they were unnecessary. Like discarding dead skin, it was letting go of defenses—revealing oneself leads to more exposure and rawness. The circles were banded together, keeping connection together.

The drawing’s tension represented eco-art therapy. Its transpersonal, approach gave me a spiritual awakening that occurred over the 5 weeks. I reconnected with the Earth and vulnerability in creating. Kopytin (2020) described an eco-human perspective or love for natural work as “a powerful human emotion [that] assumes one of the central places, since it affects the spiritual, creative essence of the human being” (p. 11). The encapsulated circles represented flow. Regardless of the worldwide changes, an interpersonal, connective flow could create a mechanism of sustenance and rebirth. Separation from this process informed me that even someone small in this vast ecosystem has the capacity for connection (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6 | Cycles: Leaf prints, paint, and color pencil.

Yermakov: We worked with fine art materials for the first time. Incorporating paint persuaded me to incorporate more thought than spontaneity. Although I matched my intention with color, I had felt more joyful using natural materials. This change brought nature’s impact into awareness—how important it is to accept being a part of rather than separate from nature.

Rather than solely experiencing Dr. Summer’s energy, an energy larger than us both—the presence of Earth itself —took the lead. I closed our sessions enjoying “just being” altogether. Unlike earlier sessions, there was no direct connection with my piece. Instead, the connection was with the physical experience and appreciation for our work, nature, and life itself (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7 | System of flow.

Conclusion

After our five sessions, we returned the natural materials to the environment from which they came. We had transformed the materials, forever changing the “landscape” where they originated. Through the eco-art exploratory process, we obtained clarity regarding what separates humans from the rest of the ecological world (plant life, nonhuman beings) and found compassion within ourselves (Kopytin, 2017). Our vulnerable moments created intimate spaces; silence and proximity allowed space for safety and trust. Within eco-art, the therapeutic process took a transcendental standpoint focused on responding to the relationship between self and other. Thus, healing streamed through the self, other, and environment. In this way, the change process can be described as relying directly on sensory responses to the unknown (Levine, 2020).

The themes and symbols that emerged from these sessions revealed aspects of our personalities. The unstructured, organic sessions offered the opportunity to play and explore like children interacting with our environment. Future explorations should include eco-art activities with marginalized and lower socioeconomic communities and youth without easy access to natural resources. We hope to educate wider audiences to increase their environmental consciousness and find their connections symbolically and internally through the process.

Acknowledgments

This project received no funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

About the Authors

Dan Summer, PhD, ATR-BC, LCAT, ATCS, is a licensed creative arts therapist and educator at Caldwell University, Caldwell, NJ. He previously worked as a clinician in various settings and published work on adolescent resilience, developmental transformations, drama therapy methods, and a mural community project to decrease gun violence. He has presented on archetypal imagery and the use of eco-art therapy with spirituality.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: Dsummer@Caldwell.edu; Tel.: +1-718–541-2509

Brigitt Yermakov is an art therapy graduate student at Caldwell University and a youth and adult crisis counselor. She is an active artist interested in developing or collaborating with a holistic center incorporating expressive therapies.

References

A’court, B. (2021). The art of tenderness: Embodied wisdom in ecological art therapy. Ecopoiesis: Eco-Human Theory and Practice, 2, 20–27.

Alt, G. (2021). The land art movement and its continued influence into the 21st century. Sculpture Review, 70, 14–21.

Atkins, S., & Snyder, M. (2017). Nature-based expressive arts therapy: Integrating the expressive arts and ecotherapy. Jessica Kingsley.

Berger, R. (2009). Being in nature: An innovative framework for incorporation of nature in therapy with older adults. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 27, 45–50.

Berger, R., & McLeod, J. (2006). Incorporating nature into therapy: A framework for practice. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 25, 6–20.

Chung, M. S. (2018). A path analytic study of self-compassion, forgiveness, and mental well-being. Information, 21, 821–830.

Davis, J. (1998). The transpersonal dimensions of ecopsychology: Nature, nonduality, and spiritual practice. The Humanistic Psychologist, 26, 69–100.

Delaney, K. (2008). Earth into art. Available online: https://depot.ceon.pl/bitstream/handle/123456789/8633/10_pjas2.pdf (accessed on July 15th, 2022).

Della Cagnoletta, M., Govoni, R. M., & Mondino, D. (2022). Embodied tree: Empowering its symbolic strength through creative arts therapy. Creative Arts in Education and Therapy, 7, 138–148.

Fisher, A. (2013). Ecopsychology at the crossroads: Contesting the nature of a field. Ecopsychology, 5, 167–176.

Franklin, M. (2001). The yoga of art and the creative process listening to the divine. In M. Farrelly-Hansen (Ed.), Spirituality and art therapy: Living the connection (pp. 97–114). Jessica Kingsley.

Geha, J. (2019). Nature as an impermanent canvas: An intergenerational nature-based art community engagement project. Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses, 113. Lesley University. Available online: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_theses/113 (accessed on July 14, 2022).

Green, D. (2021). Enduring liminality: Creative arts therapy when nature disrupts. Creative Arts in Education and Therapy, 7, 71–91.

Hocoy, D. (2005). Art therapy and social action: A transpersonal framework. Art Therapy, 22, 7–16.

Hinds, J. (2011). Woodland adventure for marginalized adolescents: Environmental attitudes, identity and competence. Applied Environmental Education & Communication, 10, 228–237.

Knill, P. J., Levine, E. G., & Levine, S. K. (2005). Principles and practice of expressive arts therapy: Toward a therapeutic aesthetics. Jessica Kingsley.

Kopytin, A. (2017). The green mandala: Where Eastern wisdom meets ecopsychology. Creative Arts in Education and Therapy, 3, 3–16.

Kopytin, A. (2020). The eco-humanities as a way of coordinating the natural and the human being. Ecopoiesis: Eco-Human Theory and Practice, 1, 6–16.

Kopytin, A. (2021). Ecological/nature-assisted arts therapies and the paradigm change. Creative Arts in Education and Therapy, 7, 34–45.

Leather, M., & Nicholls, F. (2016). More than activities: Using a ‘sense of place to enrich student experience in adventure sport. Sport, Education and Society, 21, 443–464.

Levine, S. K. (2020). Ecopoiesis: Towards a poietic ecology. Ecopoiesis: Eco-Human Theory and Practice, 1, 17–24.

Macy, J. (1995). Working through environmental despair. In T. E. Roszak, M. Gomes, & A. D. Kanner (Eds.), Ecopsychology: Restoring the earth, healing the mind (pp. 240–249). Sierra Club Books.

Macy, J. (2007). World as lover, world as self: A guide to living fully in turbulent times. Parallax Press.

Nash, G. (2021). Environmental arts therapy: Personal, professional and creative action. Ecopoiesis: Eco-Human Theory and Practice, 2, 75–78.

Pike, A. A. (2021). Eco-art therapy in practice. Routledge.

Richardson, M., Hunt, A., Hinds, J., Bragg, R., Fido, D., Petronzi, D., Barbell, L., Clitherow, T., & White, M. (2019). A measure of nature connectedness for children and adults: Validation, performance, and insights. Sustainability, 11, 32–50.

Roszak, T. (1992). The voice of the earth: Discovering the ecological ego. The Trumpeter, 9, 1–8.

Rousseau, S., & Deschacht, N. (2020). Public awareness of nature and the environment during the COVID-19 crisis. Environmental and Resource Economics, 76, 1149–1159.

Ryland, E. (2000). Gaia rising: A Jungian look at environmental consciousness and sustainable organizations. Organization & Environment, 13, 381–402.

Sang, Y. (2021). The power of compassion: The Buddhist approach to COVID-19. In J. Golley & L. Jaivin (Eds.), China story yearbook: Crisis (pp. 129–135). ANU Press.

Snell, T. L., Simmonds, J. G., & Webster, R. S. (2011). Spirituality in the work of Theodore Roszak: Implications for contemporary ecopsychology. Ecopsychology, 3, 105–113.

Sprinkle, A., & Stephens, B. (2021). Ecosexuality: The story of our love with the Earth. Ecopoiesis: Eco-Human Theory and Practice, 2, 42–48.

Swan-Foster, N. (2016). Jungian art therapy. In J. A. Rubin (Ed.), Approaches to art therapy (pp. 167–188). Routledge.

Vespa, A., Giulietti, M. V., Ottaviani, M., & Spatuzzi, R. (2018). Mindfulness transpersonal psychology and tumors: This approach may be always suitable and effective with the patient. Clinical Oncology, 3, 1–2.

Whitaker, P. (2011). Groundswell: The nature and landscape of art therapy. In C. H. Moon (Ed.), Materials & media in art therapy: Critical understandings of diverse artistic vocabularies (pp. 119–135). Routledge.

Whitaker, P. (2017). Art therapy and environment [Art-thérapie et environnement]. Canadian Art Therapy Association Journal, 30, 1–3.

Yunt, J. D. (2001). Jung’s contribution to an ecological psychology. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 41, 96–121.