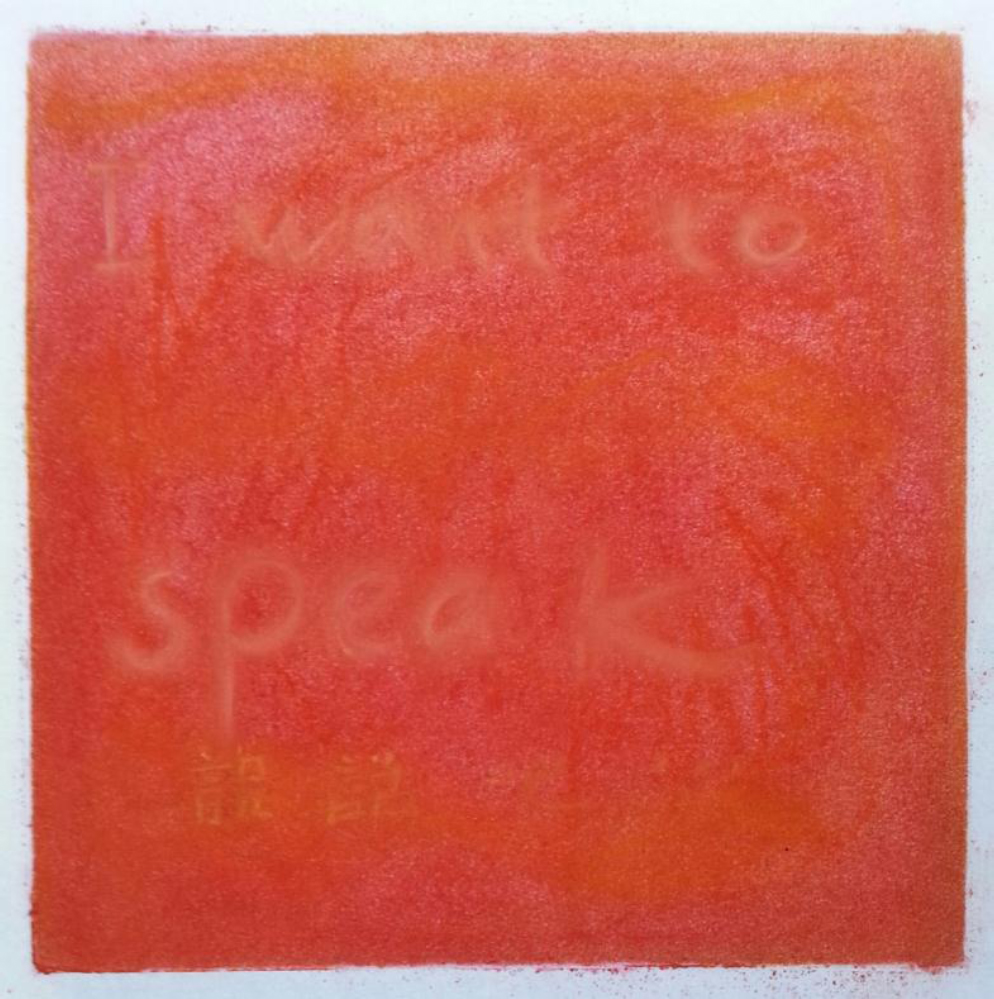

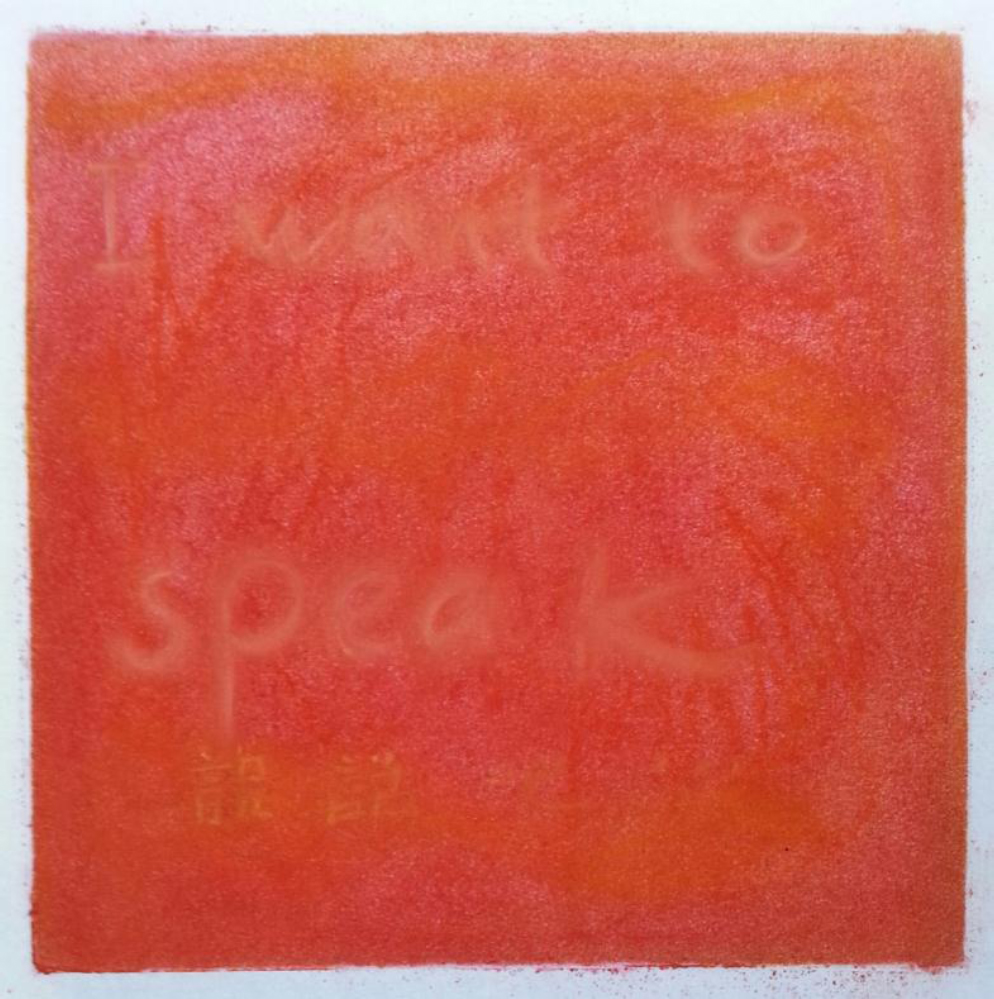

FIGURE 1 | INGRID, 2016: I want to speak (soft pastel on paper, 20cmx20cm).

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2017) 3(1):26–43 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2017/17/4 |

Stitching East and West

针线缝补东方与西方

Whitecliffe College of Arts and Design

Abstract

In this collection of creative vignettes, two immigrants – one Chinese and one African – explore difficult experiences caused by migration. The tale began several years previous to this when Ingrid Wang, an arts therapy student, grappled to express how moving from China to New Zealand has silenced her sense of self. Deborah Green, then a lecturer in the early stage of her academic career, witnessed Ingrid’s struggles and responded by drawing on her own experience of emigrating from South Africa to New Zealand. This story then moves to the present as both Ingrid and Deborah reconnect when Deborah begins supervising Ingrid’s Master’s research project and the core motif of stitching is woven throughout this arts-based conversation. Using Skype, telephone, email and snail-mail, they stitch together the geographical distances between the two cities in which they live – Ingrid in Auckland on the North Island and Deborah in Christchurch on the South Island. Through art-making and creative writing, they stitch together the metaphorical distances that manifest themselves in various ways through migration, language and cultural differences.

Keywords: Cultural connection, Arts-based research, metaphorical distances, migration, language.

摘要

在本文中汇集的短小艺术片段中,两个移民 – 一个中国人和一个非洲人 – 一起探索她们曲折的移民经历。故事是从在几年前开始的,当正在学习艺术治疗的Ingrid Wang探索着如何表达她从中国移居至新西兰后自我被压抑感受时,当时还在学术生涯初期的讲师Deborah Green目击了Ingrid的努力后,用绘画表达她自己从南非移民到新西兰的经历来回应Ingrid的故事。Deborah和Ingrid的故事随之回到现在,Deborah开始了对Ingrid的硕士研究项目的督导,两人也因此再次取得联系,而针线缝合这一象征由始至终穿插在她们的艺术本位研究的对话交流中。通过Skype、电话、电邮和信件,两人缝合了她们之间的地理间距:Ingrid住在北岛的奥克兰,Deborah住在南岛的基督城。两人通过艺术创作和创意写作的过程,缝合了她们之间由于移居经历、语言和文化不同而表现出的象征性距离。

关键词: 文化连结, 艺术研究, 象征性距离, 移居, 语言

1. I stitch myself shut

DEBORAH: My belly twirls with anxiety and excitement as I absorb the students’ tensions. One by one they are presenting creative responses to established psychological theories. I’ve come to know these students in a sideways sort of way, sliding into their lives to take up a liminal position shadowing ----- Auckland-based postgraduate arts therapy program so I may begin running it in Christchurch, a city on New Zealand’s South Island. Several students have forthright presences and, despite my witness role, they’ve pulled me into their worlds. Others are more contained. INGRID is the most extreme of these. She’s Chinese and my familiarity with her culture is scant, built from broad stereotypical brushstrokes.

INGRID: I am always nervous before a public speech or presentation. Looking at my audience, my throat is dry and my lips are cracking. I know I am well prepared as I always am, but I am anxious about forgetting words…and even more worried about my accent. And this presentation is about my accent. I am searching for any confusion in my audience’s facial expressions. I have become an expert in searching for confusion in other people’s eyes. I wish I could speak English without my accent. But I cannot. I cannot speak English without my accent behind my tongue as “our mother tongue is so great that we do not readily learn a new language without paying homage to the thought patterns, sentence structure, and accent of our original tongue” (Elovitz, P. H., Kahn, C. 1997). I hate this stubborn accent. I was a confident Chinese woman - but with English I have become shy. I am afraid to talk in public. In this class, with my arts therapy classmates, I am afraid to offer my opinions although so many times I have ideas in mind to discuss. As soon as I detect confusion in other people’s eyes, I blame my stubborn accent and then I become quiet again.

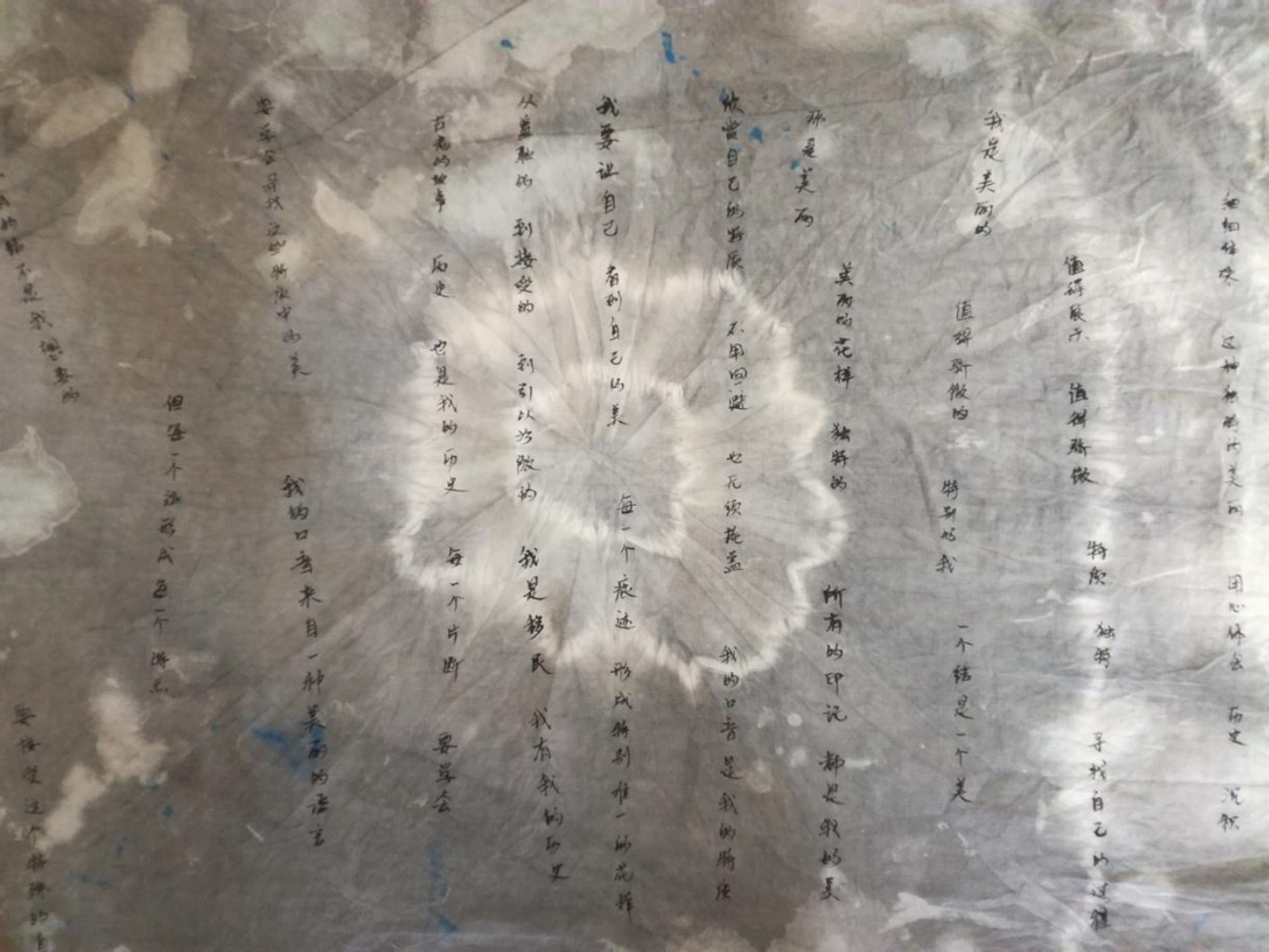

FIGURE 1 | INGRID, 2016: I want to speak (soft pastel on paper, 20cmx20cm).

I love images. This was one of the reasons I became more and more interested in arts therapy. When I make my artwork I do not have my accent in my images. In the artwork I want to speak, I used red to express my anger, frustration and shame at speaking English with a Chinese accent. The English word ‘speak’ in the image is much bigger than the Chinese word ‘说’(speak). Both English and Chinese words are fading into the red background. I want to speak but I am afraid and embarrassed about my accent.

I have often felt an outsider since, some 15 years ago, I moved from China to New Zealand. Many events have made “accent scars” on me. I will single one example out. Some years into my teaching career, my school’s restructuring resulted in a new manager running our program. During our first staff meeting, the manager started a discussion about students’ complaints from the previous term. She looked at me and said, “A student made a complaint about your accent and the student did not come to your class enough because he was unable to understand your accent.” All the staff members were looking at me and waiting for my reaction - especially the new staff members. Their collective gaze felt like disgusting cockroaches crawling from my head to my toes. My face was red and I could hear my heart pumping hard.

开不了口

我听见自己的声音,合着陌生的语调

我看见别人的嘲讽, 掺杂僵硬的微笑

我感觉心底的羞愧, 就像穿着脏衣服

倔强的口音, 蒙住了我的嘴

Can Not Open Mouth

I hear my voice

With a strange intonation

There is cruelty in their eyes

A stiff smile on their lips

I feel ashamed from deep in my heart

Like I’m wearing dirty clothes

This stubborn accent

Has covered my mouth

DEBORAH: She’s tucked into her small physical frame neatly, concisely. She is fluid - singing her word - her artwork powerful and vibrant. Next to her I feel big-boned and large-nosed, unfinished, lacking refinement, and I’m so ashamed when I learn that the seemingly unrefined, blunt, clumsy world I represent has so cauterized her fluid sense of self.

INGRID: I did not want to argue that, in the same paper, some local students presented me with flowers after their final presentation in order to express their appreciation. I did not want to point out that the student who complained about my accent also had poor attendance in other classes taught by local lecturers. I could not open my mouth to explain because I knew my explanation would become so pale and pointless with my accent. In the meeting room all eyes were on me and no one said anything. I could not remember how the meeting finished; I could only remember the chair under me was extremely hard and uncomfortable. I rubbed the fabric on the seat for the rest of the meeting.

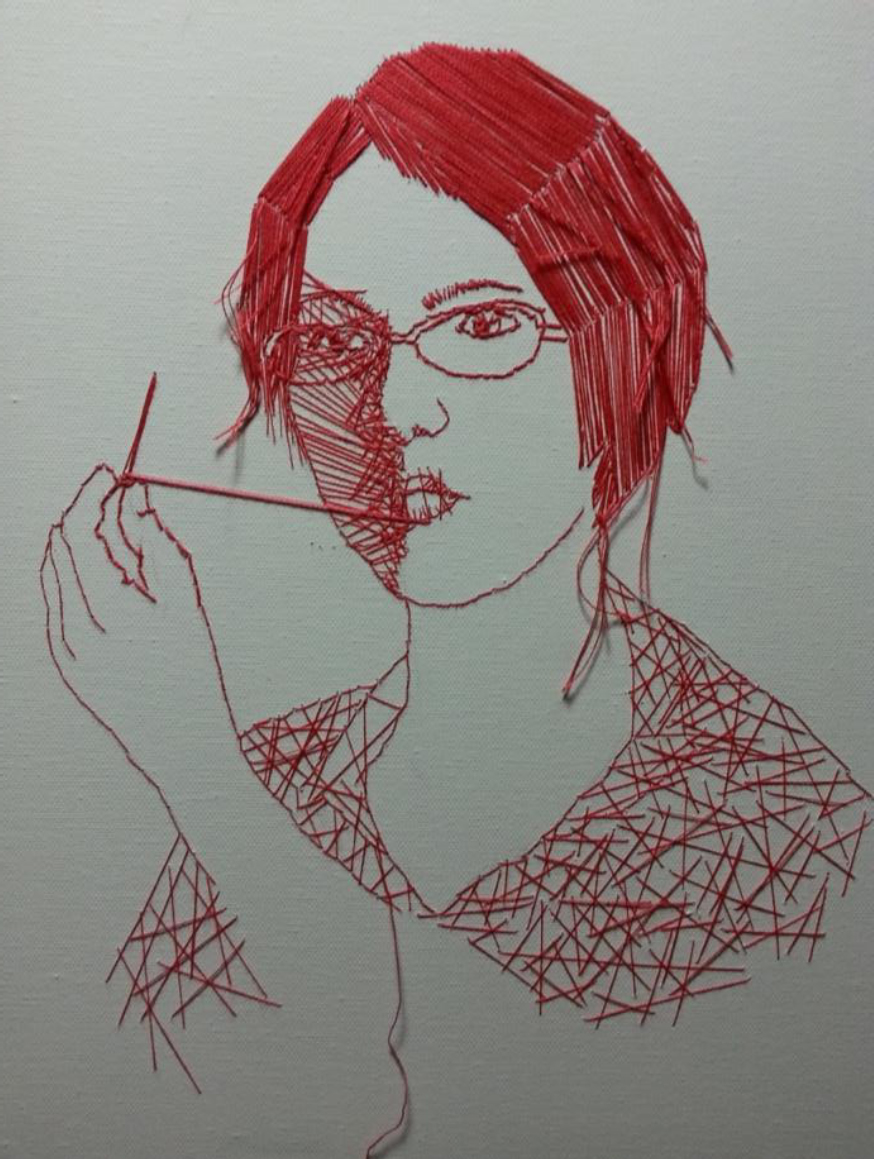

DEBORAH: INGRID has used post-modern theories as a lens to explore communication, drilling down into her experiences as a Chinese woman in a Western New Zealand English-speaking culture. A recurring image stitches her presentation together – that of mouths sewn shut – culminating in a powerful artwork that embodies how fat her lips feel when she tries to shape them around English words, how this silences her and how the very weight of trying to fit in flattens and renders her mute.

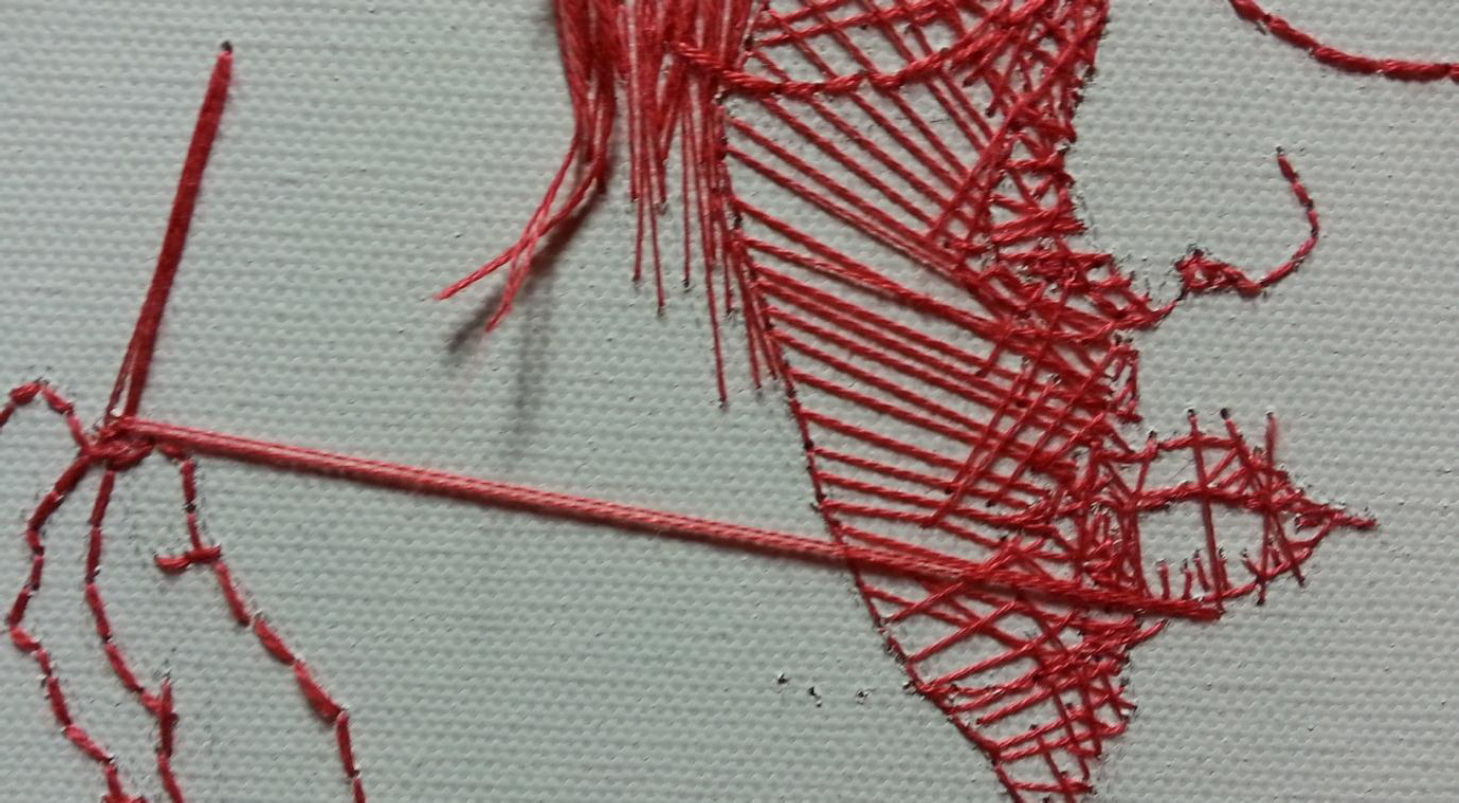

INGRID: I lock myself in my studio and focus on sewing on canvas - which is quite a frustrating process for me. The canvas is thick and tough. It reminds me of the fabric of the chair which I was sitting on in that embarrassing staff meeting. Every stitch hurts my fingers. Every stitch makes an unpleasant sound. I decided to stitch a self-portrait after I saw several online images named ‘shut mouth up’. These images are quite disturbing – lips stitched together by string with holes, bruises, scars and blood around them. These images reminded me of the pain, the frustration and the anger when I am silenced by stiff smiles, confused expressions and cruelty in peoples’ eyes. I stitch, stitch and stitch silently and imagine the needle is actually going through my skin. I stitch around my lips on the canvas – one stitch after another - and as I do so, I am imagining the pain from actually sewing up my lips. A few stitches around the lips are not enough to express the magnitude of my emotions from being silenced by an English-speaking society. I add more stitches (and scars) on the face of my self-portrait. My accent and my face are not scarred but these experiences have created scars in my mind and my heart because of my face and my accent.

FIGURE 2 | INGRID, 2016, Self-portrait detail Shut up (String on canvas, 30cmx41cm).

FIGURE 3 | INGRID, 2016: Self-portrait Shut up (String on canvas, 30cmx41cm).

DEBORAH: She’s written a poem. She reads this in English. When requested, she then reads it in Chinese. The room is very still...a moment stretched taut like the canvas she pierced with her sharp needle. She begins - her voice open and fluid and round, her lips no longer fat and unwilling, her presence no longer flattened and silenced as she becomes fully three-dimensional. There is music in her voice, in her words, in her very being; there are tears too. Her eyes brim over and my cheeks are wet in response. She’s embarrassed and apologizes – this display of emotion is shameful within her culture. No! we call out; no no no - not here! Here your tears are welcome.

After her presentation, I tell her how deeply she moved me. Our eyes are full again. We’re both immigrants - coming from other lands and other cultures - feeling our way. But here in this learning space where cultures meet and touch, we create new ways of being and doing through these tears of connection. Maybe, when your lips struggle to shape the clumsy English words and when I ache for the heavy sun of Africa, we can let this word-free connection and communication wash in; this sharing of humanness - this warmth of common tears and laughter - this can build a new creative culture big enough for both of us.

2. I stitch myself open

INGRID: In the final year of my Masters in Arts Therapy, my research supervisor, DEBORAH, invited me to revisit my stitched self-portrait. I was excited but anxious. I was excited about the possibilities - especially from working with an experienced arts-based researcher. I did not know what the revisiting process would bring for me but I was willing to open myself to the possibilities.

DEBORAH: I’ve invited INGRID and myself to re-engage creatively with her self-portrait. The lip-stitching is so aggressive, so sharp-edged, so very present. The tears we shared years ago seem only a partial response…they’re borrowed from my culture which tolerates emotional displays more readily, so once again they constitute a silencing of some form. And yet I feel they began a process of recovery - of healing and mending. Can I make this into art? I’m drawn to a roll of ivory-colored ingrained wallpaper. I dip my fingertips into black paint and press into the centre of the sheet. The embossing is resistant and rough and my fingers pop and judder, reminding me of INGRID’s chair of shame and her canvas that resisted and then popped painfully as she pushed her sharp needle through again and again. I add colors, thinking of the beautiful disturbing paintings INGRID has shown me as her responses to the painful experiences she’s having as a new Asian arts therapist in a Western country. But in order to explore ways of healing these wounds of dislocation and disowning - of silencing and shame - I need to first expose them. I seize my colorful image and tear. The wallpaper, thick and heavy with wet paint, smears and shears jaggedly. To mend these tears, I want to use stitching to resonate with INGRID’s image and then hopefully follow it somewhere new. I rummage through a box of fabric and am surprised by various snippets of gold fringe and lace and embroidered cloth. This reminds me of Japanese kintsugi; when precious porcelain is broken, gold enamel is used in the cracks to celebrate the imperfections of the break. Into my torn cracks I slide gold fabric and stitch these almost closed with red pipe cleaners. The red stitches become sutures healing wounds. They’re not hidden; they’re on display. They say, “I’m wounded but I’m also healing.” INGRID, too, is wounded while simultaneously healing. She and I share this journey towards becoming wounded/healers…we’re not only intimately familiar with our own wounds, and therefore able to empathize with clients from our embodied knowing of pain and suffering but we’re also working on healing our wounds. It’s this healing - this embrace of the ‘healer’ element of the archetype - that allows us to companion others as they too seek healing.

FIGURE 4 | DEBORAH, 2017: Detail ReStitching (Paint, pipe cleaners, fabric on wallpaper)

INGRID: I had never tried the tie-dye method, but when I was looking at the process in a video clip something made me really want to experience the making process. The fabric I used was made from natural cotton. I pinched the middle part of the fabric – I pulled and twisted it – then I twisted and twisted the fabric in my hand until I could not twist it anymore. I held the twisted fabric in my left hand and used my right hand to make a tie with a length of cotton - one round, another round then another round - the cotton was tough and strong and it was a bit painful to hold it so tightly as it rubbed the skin on my fingers. By making the ties on the fabric, I felt like I was making ties on my tongue. After the twisting, tying and knotting, the soft fabric became hard – just like my tongue does when I speak English. My mother-tongue is like the tough and strong cotton which ties my tongue - very rigid, one round, another round, then another round - so that I cannot use my tongue to make perfect English pronunciation.

FIGURE 5 | INGRID, 2017: Tie-dye process

In my process of tie-dye making, I mixed Western watercolour with Chinese ink as the dye material. In Chinese writing, the character Ink “墨 mo” is a combination of two characters “黑hei” and “土 tu” meaning ‘black’ and ‘earth’. Because of the natural compounds used in Chinese ink-making, Chinese ink is quite different from Western ink in its composition and its ability to stand the test of time and exposure to light. The main ingredient of Chinese ink is lampblack; the finest Chinese ink is made from lampblack from burning vegetable oil. This is the reason for the distinctive smell of Chinese ink.

FIGURE 6 | INGRID, 2017: Tie-dye process

When I poured Chinese ink into the water, I smelled the distinctive smell from the ink. This smell of the ink took me back to my memories of learning Chinese calligraphy and Chinese brush painting as a little child. The smell of the ink also brought back my memories of the moist and damp air of the rainy season in my hometown. I dipped my hands into the dark-coloured water and rubbed and kneaded the fabric into the water. The cool feeling of the water was quite comfortable but the muddy and dark colour made me slightly hesitant to put my hands in the dye. I closed my eyes and, without looking at the colour, I focused on feeling the temperature and flow of the water. In my mind there were images of the soft tip of the Chinese paintbrush and the rain drops on the stone steps in front of my grandma's old house. I rubbed and kneaded. The water moved and flowed. The fabric touched my skin. It was so quiet. I was totally immersed in my real and imagined memories.

FIGURE 7 | INGRID, 2017: Tie-dye process

The fabric seemed not to change at the beginning, but after about an hour of rubbing and kneading it finally turned into a beautiful blueish dark color. I took the fabric out and squeezed out as much of the dye as I could. The magic moment of tie-dying is cutting off the ties. The process of cutting for me was an emotional state between excitement and nervousness – it felt a bit like cutting the stitches from my own lips. I cut off the cotton ties very carefully to avoid damaging the fabric. Then I flattened the fabric on the table – and beautiful patterns appeared magically. The tied parts of the fabric remained light and stood out in contrast from the color-dyed background. I stood in front of my artwork and felt a mixed sense of relief and happiness. The whole tie-dye process was full of conflicts – ties, knots, and the mixing of different materials – but the results of these conflicts were exciting and refreshing.

FIGURE 8 | INGRID, 2017: Trace (Chinese Ink and water color on fabric)

After looking at this artwork for a while, I realized I suddenly wanted to write something. I used a fine Chinese calligraphy brush and Chinese ink and wrote on the fabric in Chinese. I wrote anything that came into my mind – there were not whole sentences but fragments. I just wrote and recorded “… history… my history… no need to hide...these traces…no need to cover…they are unique…they are beautiful…special…my accent…my history…my trace…my special characters…my identity…the special me…to understand…to accept…to feel proud…from heart…my special characters…to look for the beauty…to understand…to accept…to exhibit…to gather…to enjoy…to be confident…to accept myself…then others will accept me…”

FIGURE 9 | INGRID, 2017: Detail Trace

The tie-dye art making process not only allowed me to express my frustration with my accent (as if my tongue had been tied by my mother-tongue) but also inspired me to accept my history, my accent and my cultural background as the special characters of my own identity. When I am able to fully accept the conflicts between my root-culture and my newly adopted culture, I can find my power and strength to care for myself and to embrace whatever I will become. I remembered that, at the end of my presentation about my accent, my lecturer Tania asked me to read my poem in my first language. With tears, I could finally hear my true voice; I could finally tear off my calm and blank mask. I could finally express how I really felt as an immigrant with an accent. I looked at my audience and I saw empathy, understanding, acceptance and encouragement in their eyes. Now I am sharing my findings and growth from the tie-dye art making process with one of these audience members – my lecturer DEBORAH. I cut the fabric in half and write on half of the fabric some key words and the words I want to remember from my free-writing in Chinese: “…special, unique, self-identity, beauty, history, learning, self-confidence, acceptance…” Although my lecturer DEBORAH will not be able to understand my Chinese writing, I want to use my “true voice” to share these words.

FIGURE 10 | INGRID, 2017: Tie-dye process

DEBORAH: I invited INGRID into this creative journey and she’s flying. But I’m stumbling - anxious that her very tangible talent as a visual artist will show me wanting. I am, after all, her lecturer and supervisor. I invite myself to sit with this; here is my humanness, my fear of failure and my wanting to be perfect. Here are my stereotypes of what a leader should be…hello.

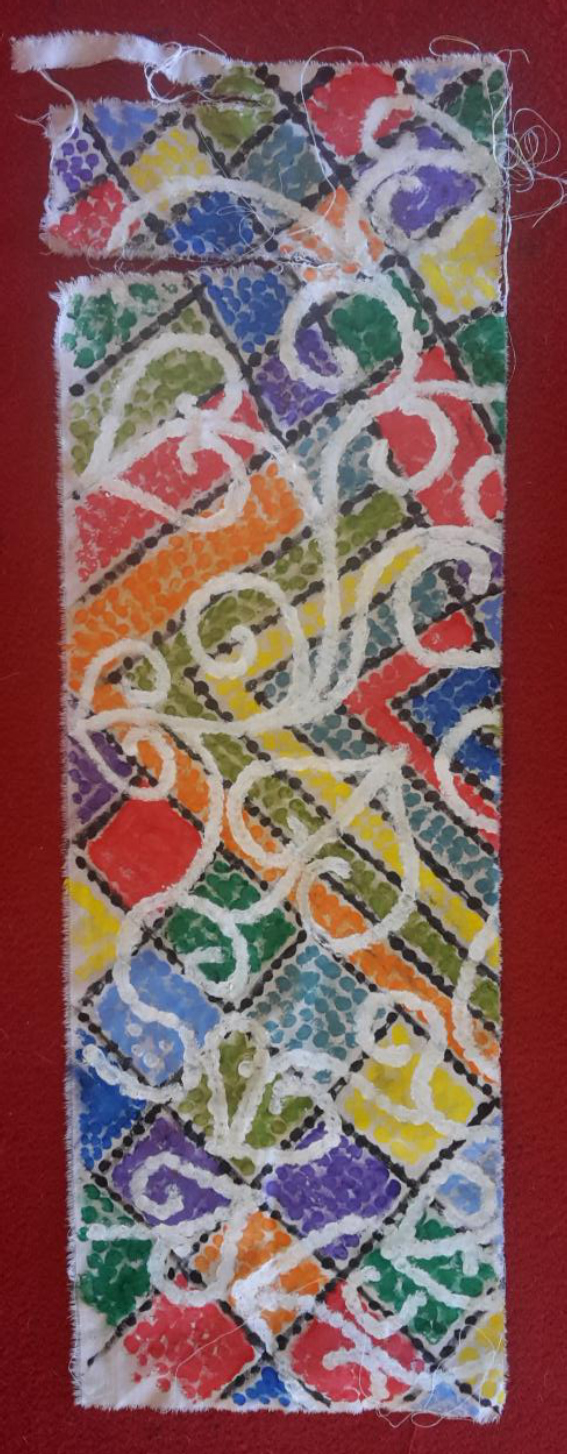

In this place of contemplation, I gather cloth and paint. I think about where I’ve come from - the warmth and red soils of KwaZulu-Natal, the deep blue sky, the purple Drakensberg mountains, the harmonious singing of my Zulu friends and colleagues and the bright Zulu beads that tell stories through how they’re stitched together in patterns and colors. I begin dotting black patterns onto cloth and soon I’m just enjoying the rhythm of dot-dot-dotting in rows and squares and zigzags. Finally I sit back and contemplate the maze of dots, the roads and fences, the skeletons of thoughts. I add colors. This doesn’t go well. The paint isn’t consistent; it soaks and smudges. I’m grumpy; wanting this to be over. It’s ugly. I feel ashamed.

I breathe and open my wondering. I realize this bitty and inconsistent image actually feels accurate. I’m no longer only African; I’ve lived in Scotland, England and in Australia and have now made New Zealand my home. These journeys have both blurred and added to my sense of self as African. I smear the dots with a fingertip. Some blur easily; others resist. This tells stories of the bits of me that have compromised, adapted, grown and transformed while also revealing the stubborn bits that remain fixed, untouchable, or lovingly sustained. I now want to depict my new home and how it speaks to this underlying image. I’m a collection of beads of thought/feeling/experience/inheritance stitched - and being stitched - together again and again on the canvas of self, so I apply my pointillist dotty technique again. Rounded organic shapes sing of the Kiwi ferns – the koru – and swirl in white over the squares and chevrons and triangles of the African beading. The finished piece is rough-edged - like me. The paint, dry in some places, makes the fabric stiff; in other places it allows it to be flexible – just like me. The two very different color - and shape - choices create contrasts, harmonies, discords and enhancements - just like me. I tear the cloth with a little wrench and send my piece to INGRID.

FIGURE 11 | DEBORAH, 2017: Painted fabric

3. We stitch ourselves together

INGRID: When the post arrives, I am excited and curious. My lecturer DEBORAH has created an artwork for me to integrate into my art-making exploration of this topic of accent. I open the bag - and the first thing I see is colours. This is very different from my almost monotone artwork (of which I sent half to DEBORAH); her work is full of bright, bold colours. The fabric is soft but the layers of colours have made the fabric stiff in some places. I can feel the textures of the dots through moving my fingers lightly over the patterns.

I did not really know much about DEBORAH’s personal life and history, but I knew she migrated from South Africa. Compared to my other lecturers, she was always a bit different. She had a slightly different accent in her English but I liked to listen to her speaking as if I almost could hear the music and rhythm of a foreign land behind her tongue. When she was in our classes, she was always smiling, warm and so energised. She was always very understanding and empathic, so when I made presentations in class I liked to seek out eye contact with her as I could always find supportive warmth from her. I found all of these qualities also existed in the artwork which she sent to me; the pure and vibrant colours remind me of her warmth and energy and the heart-shaped patterned lines reminded me of her support and empathy. Looking at her beautiful artwork, I feel reluctant to cut up her work and combine it into my own piece.

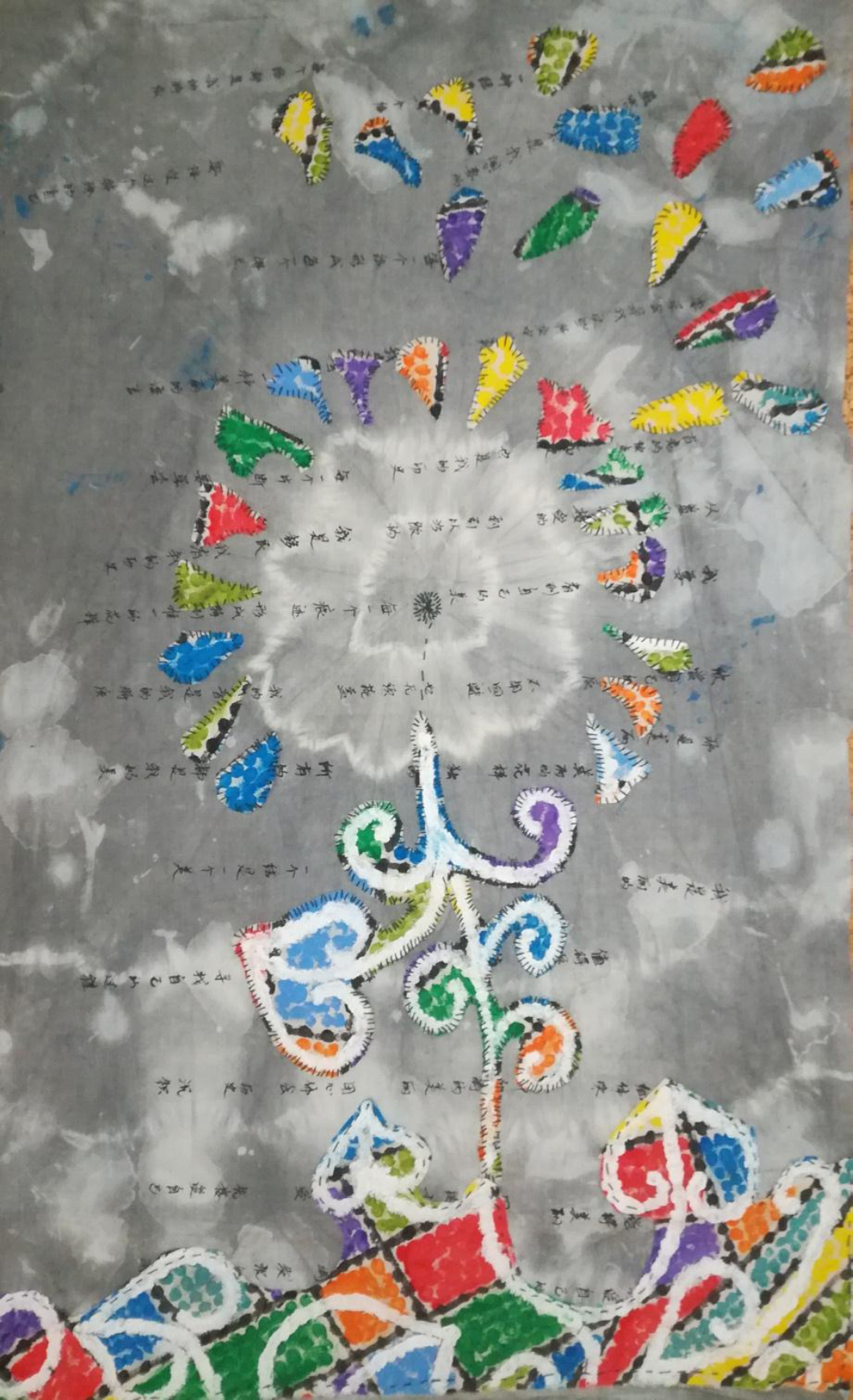

I close my eyes to imagine what my artwork would be like if there were colours. The first image to appear in my mind is a flower. I follow my thoughts and I allow the flower images to flow, to enlarge and to become detailed in my mind. The flower-like pattern in the middle of my tie-dye artwork starts glowing. In my imagination, I can almost see the sunlight behind the flower; I can feel the breeze around it. I can smell the fresh soil under it and I can hear my mind singing happy tones. I feel a sense of flying. I suddenly know what the flower is in my imagination – it is a full-blooming dandelion. I want to capture this imagined dandelion image. I start cutting and stitching the artworks together. I trim around DEBORAH’s heart-shaped lines carefully. These heart-shaped lines become the stem of the dandelion. Bright and vibrant colours become dandelion petals. Little by little - one stitch after another - the dandelion image starts blooming on the artwork.

FIGURE 12 | INGRID, 2017: Detail Dandelion

DEBORAH’s artwork and my artwork have both been made on soft cotton fabric. Stitching two layers of soft cotton together is relaxing. I turn on soft music and sit on a comfortable arm chair. Every stitch I make is tidy and neat. I am completely focused on the whole process because the dandelion image in my mind is strong and comforting. It is a very different stitching experience compared to the process of stitching my mouth-shut self-portrait. When I was stitching my self-portrait, I was expressing pain and frustration; when I am stitching my dandelion artwork, I am visualising hope.

FIGURE 13 | INGRID, 2017: Dandelion

From this art-making process, the dandelion has emerged as the inspiration for me to grow, to heal, to survive and to rise above life’s challenges. DEBORAH’s artwork provides the support - like the soil and stem - for me to begin healing from the emotional pain I felt of being silenced by the English-speaking society. Her artwork also helps me to find the strength within myself. I feel a sense of relief and freedom as if I am the dandelion petals held in a delightful breeze and the sun’s comfortable rays and I am flying to find my next patch of nutritious soil. That nutritious spot is full new possibilities for the dandelion’s new growth.

DEBORAH: INGRID’s cloth has arrived! It is comprised of subtle, gentle greys and off-whites with a splash of blue in quiet star-burst patterns; over this watery landscape black Chinese characters skitter like little insects. I’m entranced. I place it next to my cloth and my delight drains away – they’re so very different! How will I ever stitch them together? For several days they hang side by side so I can see them often. Finally, I accept that I can’t stitch them together. They don’t want this. They’re asking me to find another way to use the stitching motif that allows them to connect but remain independent.

I decide to make two dolls. I start with plain cloth torn into strips. I bind stick bundles to create two doll bodies. I adorn a doll with my fabric – a small headdress and dress appear that feel quite African. I’m sitting outside in the early autumn sunshine and drinking Rooibos tea…and I’m happy. I wind red and gold thread about the body to continue the theme that has emerged.

I pick up INGRID’s doll. I feel anxiety again. What if I screw up? I’m her lecturer, her supervisor; I’ve responsibilities to be better at this arts therapy stuff than her…don’t I? Holding INGRID’s fabric gently, I smile wryly at myself. Yeah, right. What’s happened to your Freire-ian leanings and your beliefs that we’re all experts in our own lives and that learning is about sharing? Taking a deep breath, I tear INGRID’s cloth and wrap some around the second stick doll. It asks to be form-fitting so I wind it tightly and secure it with red and gold.

I create clay faces. My face doesn’t get a mouth - I talk too much and can dominate INGRID with my yappy mother-tongue – so I remove the temptation. When I create INGRID’s face, she needs an open mouth - a mouth freed from the red stitches - a mouth from which golden threads now stream.

The dolls feel primitive, aboriginal; I could cast spells with them. I cast a spell for connection. This spell encourages me to use the remainder of INGRID’s cloth as the ground on which these dolls will meet. I lay the cloth over a canvas… and suddenly I’m nervous again. I’m about to replicate INGRID’s process of stitching with red thread. Will my needle will pop painfully like hers? I breathe and push the needle in. It makes a popping sound. It is a little shocking - but I’ve done it - and I continue pop-pop-pop as the needle bursts through the canvas. I’ve no plan and simply place random stitches…and then I notice my stitches are forming into childlike versions of INGRID’s beautiful black Chinese writing.

I stitch the dolls in place using golden threads and then find I’m bridging the gap between them…golden strands from INGRID’s mouth tiptoe across the canvas and wrap their tendrils about my heart. I become uneasy – this feels transgressive as if I’m impinging or disclosing too much. I’m explicitly showing a student that I’m moved by her words and by her struggles and that she has tugged on my heart-strings. But as I write these words I realize this is how we heal…is it not? This honesty and cnnection, this vulnerability - saying to another, “I see you. You are real. Your struggles are real. You have moved me. We are now connected by these threads of emotion. . .emotion.”

Figures 14 & 15 | DEBORAH, 2017: Connecting Threads (Printed fabric, sticks, thread on canvas)

INGRID: I read DEBORAH’s words and look at the image of her artwork. I am humbled and touched. “I see you. You are real. Your struggles are real. You have moved me. We are now connected by these threads of emotion.” This process of working with DEBORAH has shown me a different side of her. In my class, she is my lecturer. For my research, she is my academic supervisor. In this co-creative process, however, she is like a friend, a supporter, a witness, a listener and another immigrant who can understand my struggles and pain. I feel I can be honest, authentic, and just be myself in the whole process. Every time I see her work and read her words in response to my own work and writing, there are tears on my cheek and warmth in my heart. Every time after receiving images and writing from her, I feel I am ready for my next phase of growth. Through this process I have learned that I am not alone. There are many people - not only Asian immigrants - sharing similar experiences of displacement and sharing similar feelings of pain and frustration from being silenced. My connection with DEBORAH encouraged me to be creative and brave, to let my art-making and writing inspire me to feel comfortable about my accent, to be proud of my own culture and history and to value all my life experience as part of who I am. My creative conversations with DEBORAH have not only given me the chance to open my mouth but have also given me the strength to have my own voice. Now I can say to her, “I see you. You are real. Your compassion is real. You have encouraged me to grow. We are now connected by these threads of emotion.”

About the Author

Deborah Green, PhD, MAAT(Clinical) AThR MEd PGDip(Adult Ed) BA(Hons)(Drama). Deborah began her career as a drama and adult education lecturer, lifeskills/AIDS educator and counselor, and community developer for the South African University and Health sectors. She gained her clinical Masters in Arts Therapy through the Whitecliffe College of Arts and Design after she moved to New Zealand. Following the Canterbury earthquakes in 2010/11, she has spent several years providing arts therapy for quake-affected adults and children and was awarded her PhD through the University of Auckland for an arts-based thesis exploring this work. She has published in ANZJAT, and presented at various conferences in Australia, Singapore and New Zealand. She currently holds the position of senior lecturer and course coordinator in Arts Therapy for Whitecliffe College. Email: deborahg@whitecliffe.ac.nz

Ingrid (Ying) Wang, MDes PGDip(Design). Ingrid has been working in the creative field for almost two decades as a designer and design lecturer. She has a Master in Design from Massey University and lectured in design at Massey in Wellington and Unitec in Auckland before deciding to follow her dream of becoming an artist and arts therapist. Her current research interest is the relationship between art and arts therapy. She is now a practicing artist and an emerging arts therapist. She has worked in arts therapy field across diverse environments, including disability, palliative care, addictions and mental health.

References

Elovitz, P. H. & Kahn, C. (1997). Immigrant experiences: Personal narrative and psychological analysis. London: Associated University Presses. p. 14