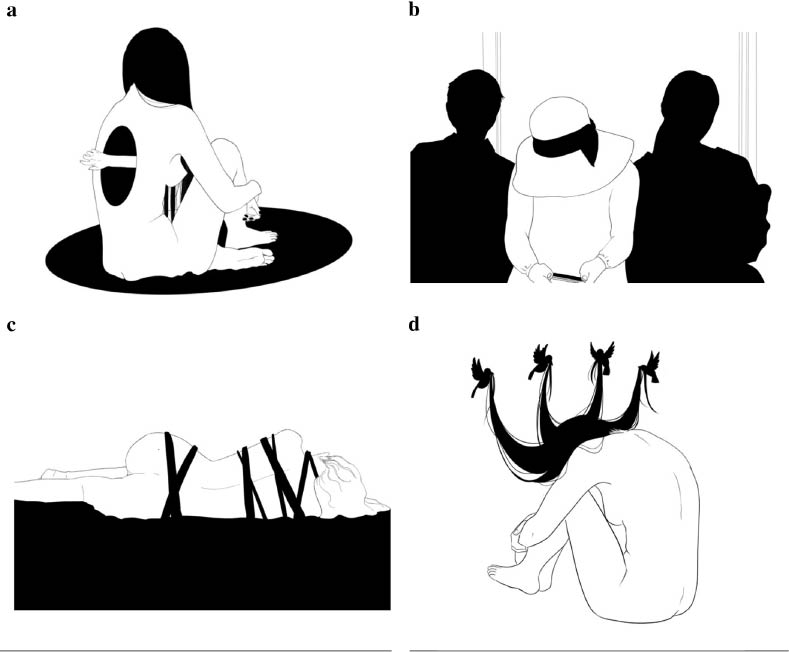

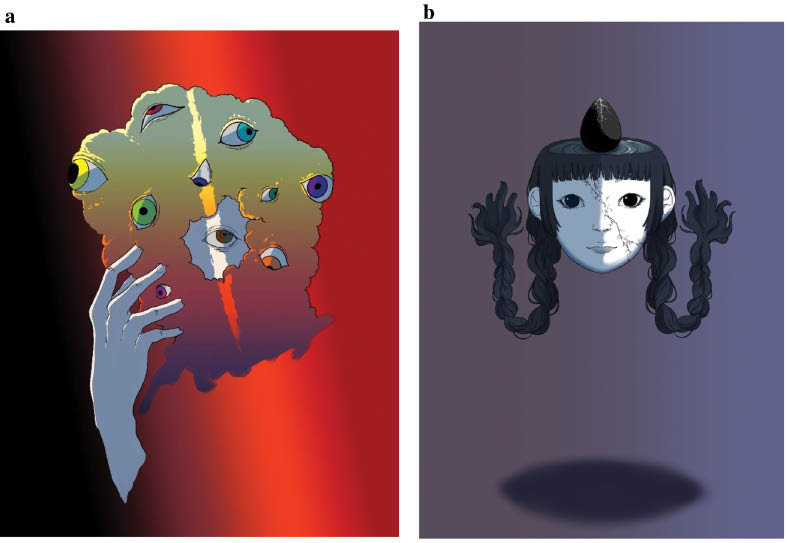

FIGURE 1 | (a) “Escape「逃亡」,” (b) “Lonely「寂寥」,” (c) “Struggle「苦闘」,” (d) “Delusion 「妄想」,” Digital black-and white paintings by Yuri Mochimaru.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2022) 8(1):99–112 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2022/8/16 |

Digital Art Therapy and Social Withdrawal in Japan

日本的数字艺术治疗和社会退缩

デジタルアートセラピーと日本のひきこもり~孤独とは何か~

Endicott College, USA

Abstract

This article discusses the use of digital art-making as an approach to examine the themes and outcomes of the Japanese mental health crisis, known as hikikomori, and its relationship to coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). In Japan, more than 1 million people experience Hikikomori, which is characterized by self-isolation for a period of at least 6 months. With the technology generation on the rise and increased comfort in using social media for creative expression and communication, the use of digital art-making may offer a meaningful therapeutic mode to express thoughts and feelingsduring a time of social withdrawal. The work presented in this article was conducted as part of a year-long senior thesis for undergraduate BFA degree in art therapy at Endicott College in Beverly, MA, USA, while the first author was in isolation in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Twelve hand-drawn digital paintings were created with Clip Studio Paint Pro for Windows. The paintings are discussed from the artist’s perspective on Hikikomori and while living in isolation during the pandemic. Further recommendations toward the use of digital art as a mode of art therapy for managing feelings of loneliness and depression are discussed.

Keywords: social isolation, Hikikomori, digital art, art therapy, Japan, undergraduate, arts-based research, COVID-19 pandemic

摘要

本文讨论了使用数字艺术创作作为一种方法来探讨日本心理健康危机(称为隐居青年,Hikikomori)的主题和结果,以及隐居现象与 2019 年冠状病毒 (COVID-19) 的关系。在日本,超过 100 万人经历过隐居(Hikikomori),其特点是自我隔离至少 6 个月。随着科技一代的兴起,使用社交媒体进行创造性表达和交流的舒适度提高,使用数字艺术创作可能会在社交退缩的年代为表达思想和感受提供一种有意义的治疗模式。本文中介绍的工作是美国马萨诸塞州贝弗利市恩迪科特学院美术治疗本科学士学位为期一年的毕业论文的一部分,而作者在 COVID-19 全球疫情期间被隔离在日本。作者使用适用于微软的优动漫插画创作软件(Clip Studio Paint Pro)创作了十二幅手绘数字画作。这些绘画作品从艺术家的角度讨论了隐居现象(Hikikomori)以及在全球疫情期间的隔离生活。文章对使用数字艺术作为应对孤独和抑郁感的美术治疗模式也给出了进一步的建议。

关键词: 社会隔离, 隐居青年(Hikikomori), 数字艺术, 美术治疗, 日本, 本科生, 基于艺术的研究, COVID-19 全球疫情

Introduction

“Hikikomori” is one of Japan’s biggest social issues. It is characterized as chronic mental illness often diagnosed in young adults who go into a prolonged social withdrawal; essentially isolating within their parents’ homes for a duration of 6 months or more all while avoiding participation in society, school, or work. The disorder is manifested by symptoms of depression, anxiety, and fatigue (Koshi & Aoki, 2017; Berman & Chen, 2022). To date, Hikikomori has not been included in the DSM-V and this is mainly due to a lack of data and test studies, however, Teo and Gaw (2010) proposed that Hikikomori should be included in that its characteristics are classifiable among current diagnosed psychiatric disorders. Related psychiatric disorders include avoidant personality disorder, Internet addiction, depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, social anxiety disorder, and sometimes psychosis. As a result of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) lockdown restrictions, which promoted social isolation, and with the accessibility of social media to young adults, the maintenance of such isolation became acceptable. Hikikomori may have been recently exasperated, particularly in Japan (Gavin & Brosnan, 2022).

In Japan, people with Hikikomori are shunned and considered unacceptable in society. The Japanese society favors finding connections to social groups and living within social norms. With COVID-19 at play, the ability to socially relate to others was diminished, while Hikikomori intensified. While digital platforms may have encouraged social media and deepened the acceptability of staying in our homes, the lack of social engagement may naturally procure mental health problems. Art may be the key to unlocking the anxiety and depression that manifest in social isolation. With the accessibility of digital art tools, people can find a means of self-expression, communication, and dignity through digital artmaking.

Literature Review

Social Isolation

Social isolation has been historically defined as distancing from others psychologically, physically, or both. Isolation, as related to loneliness, aloneness, apartness, or solitude, has prompted researchers to argue the definition of social isolation that depended on the situation. According to Biordi and Nicholson (2008), there are two types of isolation: voluntary and involuntary. Voluntary isolation occurs when people chose to isolate themselves for a variety of reasons such as for their own privacy. In contrast, involuntary isolation is described as forced solitude. Klinenberg (2016) suggested a link between social isolation, feeling lonely, and living alone; however, it is certainly possible to solely experience one of these feelings during social isolation. Primack et al. (2017) defined social isolation as a state of lacking a sense of social belonging, engagement with others, and fulfilling relationships. After investigating the relationship between social media use and social isolation in the United States, Primack et al., surveyed a nationally representative sample of U.S. young adults aged between 19 and 32 years. They looked at the time and frequency of using social media such as Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat, YouTube, Instagram, Reddit, Vine, LinkedIn, Google+, Tumblr, and Pinterest. The researchers found that young adults with high social media use were considered to be more socially isolated than those who were not actively engaged in these social media platforms. Instead of going for walks outside and having board game nights, young adults gravitated toward social platforms. Social relationships are one of the most important components of living a healthy life, and research has identified that healthy social relationships may be the key to longevity. Studies has suggested that social isolation may carry a higher risk for mortality (Stokes, Xie, Lundberg, Glei, & Weinstein, 2021) and can be as damaging as smoking 15 cigarettes a day (Berkman & Syme, 1979). Social isolation is experienced around the world through the manifestation of loneliness. Loneliness, however, does not simply arise from a lack of social interaction with others, but rather when those social relationships are poor or unfulfilling (Matthews et al., 2016). In sociology, “loneliness” is subjective, and “social isolation” objectively refers to a person’s situation (Fujimoto, 2012). Although social isolation and loneliness tend to occur at the same time, they could be experienced independently. Matthews et al. (2016) commented that a common factor between social isolation and loneliness among adults is that they both manifest as depression in that population.

Japanese Culture

Japan is a country known for its lifespan longevity, where some of the world’s oldest and healthiest people live. An article published by the BBC in 2020 referred to the island of Okinawa in Japan as the island of “almost eternal youth” and attributed much of this claim to the tight-knit social relationships and bonding that occurs among the island’s residents (Bedford & Fukada, 2020). Japan is an island located in the northwest Pacific Ocean of East Asia. The country has 47 prefectures and a population of 126.2 million, and the primary language is Japanese. In Japan, the traditional value, “Wa (和)” has been preserved. Wa means to be in a relationship of valuing and cooperating with each other. Hiragana Times, a Japanese magazine produced for foreign residents who are learning the Japanese language, described Japan as having a strong sense of fellowship and group identification. For one to really blend in with Japanese society, or be part of the culture, they need to be in harmony with the Japanese people. There is an emphasis on shared social interests, and belonging to a social group is central to acceptable Japanese behavior (Hasegawa, 2006). In Japan, people who disrupt the philosophy of the “Wa” in a group are disliked. Even school-aged children are encouraged to form social groups and social identifications. When there is trouble in a group because a person is not following group norms, such person may be kicked out—a phenomenon in which exclusivity to other groups and individuals is strengthened in order to increase the cohesiveness of “Wa.” The sense of kicking someone out of a group result in a bullying structure by emphasizing “Sa(差),” which means “difference” in Japanese (Hayashi, 2008).

Xu (2009) analyzed the social construct differences between the Japanese and Chinese cultures. In Japan, harmony is more valued than self-assertion, with a tendency toward negativity and ambiguous expression. Meanwhile, in China, it bodes well to be individualistic or different from others, and there is a strong tendency to express one’s opinions and demonstrate the authenticity of feelings. Because harmony and respect for others are important in Japan, most people have a difficult time saying “no.” In Japanese culture, saying no often means a sign of disrespect. Most Japanese are educated to respect their boss and elders, and rejecting requests from those people may be show a disrespectful attitude within the society. In fact, Kimura (2008) compared how Japanese, Chinese, and Korean students dealt with a problem in a café. Japanese students simply apologized to the staff, which is consistent with “conflict avoidance type.” Meanwhile, the students in the other groups (Chinese and Korean) explained and/or argued the problem rather than simply apologizing. Because Japanese people are eternally valuing “Wa,” they adjust themselves to people around them, as it is most important to value the Japanese tradition.

The “Hikikomori” Phenomenon

The word “Hikikomori” became known in the late 1990s, and by 2015, the number of people diagnosed with Hikikomori was approximately 696,000; however, approximately 1.55 million people are undiagnosed and are feeling a lack of intimacy and loneliness. From 2009 through 2015, the Cabinet Office in Japan investigated the percentage of people with Hikikomori according to age. They found that 17% of the total number of people with Hikikomori were between 60 and 64 years, and 70% of them were men. The second highest number was 14.9% (20–24 years). The most common reasons were retirement, followed by relationships, illness, and negative job-hunting results. Among those 40 to 64 years, Hikikomori occurred during job hunting. The researchers said it may have been affected by the Employment Ice Age, which is a period when getting a job was difficult. When they asked about lifestyle in three stages, top, middle, and bottom, one in three chose the bottom; 34% were being assisted by their parents, 30% were making a living by themselves, 17% had a wife/husband/partner, and 9% were getting welfare. Furthermore, 40% of the people said they do not consult with anyone regarding their concerns (Cabinet Office, 2015). When it comes to treating hikikomori, Teo (2009) suggested a combination of psychotherapy and psychopharmacology. However, most people with Hikikomori are not interested in treatment, so it does not apply to all individuals (Teo, 2013). On January 16, 2020, Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare confirmed that COVID-19 infected people in Japan for the first time. The infected person was a Chinese man who lived in Kanagawa Prefecture. He returned to Japan after staying in Wuhan, and his father, who lives in Wuhan, was also infected. The Chinese New Year began on January 25, and many Chinese people traveled around the world, which was one of the reasons for the spread of the virus worldwide (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, 2020).

As the government announced a state of emergency in May, people had to stay at home and limit the time for going out. According to Takahashi (2020), a network news department reporter, people with Hikikomori said COVID-19 ruined the chance of overcoming hikikomori. People with Hikikomori usually stay home, and other people try to get them out, but now, the government is asking them to stay home. People with Hikikomori felt more negative because they feel even more criticized for not working, and the increased time with their parents made them more anxious. A social worker, Hasegawa (2006), said people with Hikikomori should continue with the same lifestyle they had before the pandemic. He suggested that if people with Hikikomori will continue to stay at home, the chance of getting infected should be extremely low, and it will be a good idea to stay away from pessimistic information and news reports.

Meanwhile, online meetings for hikikomori were held in various places to discuss the recent state using online apps such as Zoom. By having many people experience the “Hikikomori” phenomenon, more people can understand the feeling of people with Hikikomori Hasegawa (2006) hoped that the prejudices would be removed and others would regard people with Hikikomori differently.

Digital Art in Therapy

Although many psychotherapies increasingly use digital platforms in therapy, such as telehealth formats, there has been a growing interest in developing arts-based technologies that provide increased presence to digital art therapy. Malchiodi (2018, p. 33) described digital art therapy as a newer mode of art therapy and defined the approach as the use of “all forms of technology-based media, including digital collage, illustrations, films, and photography that therapists used to assist clients in creating art as part of process of therapy.” McNiff (2000), suggested Photoshop, with its digital painting tools and capability to edit and alter photographs, as a meaningful therapeutic tool in art therapy. Although digital painting only needs computers, software, and peripherals such as a mouse and stylus, McNiff discovered that he could use painting techniques with traditional media, and the use of a mouse achieved a unique and free expression than an actual paintbrush. Art therapists have utilized a variety of digital media before telehealth became a more common mode of practice. Zubala, Kennel, and Hackett (2021) reviewed more than 400 pieces of literature related to current practices for digital art therapy. Although the authors concluded that there may be limitations in terms of confidentiality (especially in telehealth), along with potential technical issues, and cost of equipment, there are however many benefits; such as accessibility to those clients who cannot physically come to the therapist, which may include family members. In addition, anonymity among groups may be easier to obtain, as well as feelings of increased comfort and less self-judgement versus working with non-mediated materials—mediated materials can allow for everyone to be on the same page by minimizing or limiting the use of so many art materials.

For the youth, digital technology such as tablets and computers have been profoundly beneficial, as Neavel, et al. (2022) suggested that the youth feel intrinsically comfortable using such technologies. As technology has developed recently, touchscreens give clients opportunities to experience drawing and painting through hands-on-screen expression. The drawing applications provide a wide range of colors, brushes, and pencils, and clients can remove and paint very quickly. In fact, Darewych, Carlton, and Farrugie (2015) found that drawing on a tablet was mess-free for clients with olfactory and tactile sensitivity. There was evidence that young clients do not need the same manual skills as a pencil or paintbrush in digital drawing (Malchiodi, 2013). In fact, children with autism spectrum found it is less frustrating than when drawing with pencils on paper, thus helping them improve their creativity.

Jamerson (2018) explored how digital art had an impact on adolescents both therapeutically and educationally through expressive remix therapy. Jamerson defined the word “remix” as analogous to reframing, rewriting, or revising. Clients remixed their own narratives through digital media art and created projects such as digital storytelling, animated masks, comic voices, magazine covers, and original movie poster designs. Jamerson said, youth are experts on social media, and they feel more comfortable online chatting than talking face to face, which makes digital media an easy and meaningful process for adolescents to express their stories.

In Japan, Ito (2014) offered digital art therapy sessions at the Stress Care Tokyo Ueno Clinic. Many patients visit the clinic to solve problems peculiar to adolescence and developmental problems that are difficult to solve with drug therapy alone. Ito found that digital art allowed the patients to expand their expression and put participants on the same level by offering a common material. Sometimes, when people are offered various art materials such as paint, pastels, or 3D media, they may be limited by medical or sensory needs, and digital media can allow for cohesive and level opportunities to respond.

Methods

This arts-based research took place in Yokohama, Japan, where first author and artist Yuri Mochimaru lives and works. All artwork was created by Mochimaru using pencil and paper, photographs, and digital media. Materials included Microsoft Surface™ Book, Windows 10 Pro, Surface pen, Sonyα 7II (SEL50m28), iPhone XR camera, Clip Studio Paint Pro for Windows, a mouse, and a keyboard by Elecome, a sketch book sized 8×11 inches, 0.3-mm sharpener, a sketchbook, and a pencil. To investigate the narrative of social isolation, the artist/researcher began by taking photographic self-portraits using an iPhone XR camera with a 10-second timer. After the photos were reviewed, Mochimaru drew figurative sketches of her photos with pencil. The photographs, along with the book 極上の孤独 Supreme Solitude by 下重暁子 Akiko Shimoju (2018), inspired themes to inform the digital art process. After the sketches were finished, Mochimaru took more self-photos, positioning her body in ways to reflect the themes that emerged from her initial reference photos and Shimoju’s book. The photos were uploaded to the Microsoft Surface™ Book and the images were inserted into Clip Studio Paint Pro. Mochimaru drew the outline of the photo as a reference, and then, the photo was removed. Each digital drawing began with a draft layer in light blue pencil, and on the second layer, a black pen was used to create the final outlines. Black-and-white illustrations were used in the first series, which was followed by a second response to the black-and-white, as a colored series which focused more on Mochimaru’

Results

The methodology resulted in two series of digital illustrations. The first was a black-and-white series of digital paintings, and the second was a colored series of digital paintings. Each series identified themes related to the artists’ inferred emotional experiences and personal inquiry toward the people with Hikikomori during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Black-and-White Series

Four themes emerged within the black-and-which series, which were each illustrated in a single digitally painted portrait. The use of black and white was deliberate in order to focus purely on the emotional state through body posture and line form without using color to insinuate any additional perceptions. The themes of emotional state in the black-and-white series included escape, loneliness, struggle, and delusion, which became the unique titles of the drawings.

Figure 1a, top left panel, “Escape 「逃亡」,” shows the diagonal back view of a naked adult female. She is sitting on the middle of a black round carpet and holding her right knee. On her back, there is a black hole, and an arm is coming out from the hole. The source of the arm is unknown, and the fingers attached appear curled and almost reaching outward for something unknown. The arm from the hole appears thinner, smaller, and frailer than that of the female figure. The woman has long black hair that is parted in the middle and lays over her front, partially covering her breasts. The woman is sitting upward, and her head and neck appear slightly hunched over as she faces away from the viewer. The black oval-shaped carpet that the woman is sitting on provides a soil like appearance that seems to lightly engulf the seat of her body like moss or thick quicksand.

FIGURE 1 | (a) “Escape「逃亡」,” (b) “Lonely「寂寥」,” (c) “Struggle「苦闘」,” (d) “Delusion 「妄想」,” Digital black-and white paintings by Yuri Mochimaru.

Figure 1b, top right panel, “Lonely「寂寥」,” shows three people sitting on the seats of a train, two of whom have black silhouettes, one male and one female, who are on either side of a woman dressed in white. The two silhouettes without a gradient change, floating in the background, while the focus is on the person sitting in the middle. The person in the middle is drawn using thin lines, around stark white. The middle figure is wearing a hat with black bow while looking at a smartphone and holding it with two hands. The middle figure has her head down in isolation. Although physically surrounded by other people, the figure in the middle shows a lack of social connection, displaying loneliness and solitude.

Figure 1c, bottom left panel, “Struggle「苦闘」,” shows the back side of an unclothed woman laying down on her side on a black ground. Thick black bands are strapped tightly around her upper body, chest, neck, torso, and waist. The female figure is drawn using thin lines without gradations in shade. Her hair falls to the side, with additional lines to represent a wavy texture. On her back and right leg, there is a line to reveal the depth of the figure’s back. While the thickly bound wrap around the woman may represent struggle, the depression of the dark bed underneath holds the figure in place, almost negating the struggles the woman sinks into the black foreground of the illustration. Mochimaru did not intend for the woman to give up on the struggle, but there is a sense of a loss in the fight where the woman succumbs to the sensation of being bound and unable to escape.

Figure 1d, bottom right panel, “Delusion 「妄想」,” illustrates a familiarity to “Escape 「逃亡」,” as a woman sits flat on an unseen flat surface, hunched over, and holding her knees. The woman’s face looks down and is unrevealed to the viewer, who sees only the left side of the figure. Four small blackbirds with their wings stretched out hover above the figure’s head. Each bird holds a bundle of her hair in its beak. Strands of hair loosely dangle from the bird’s mouth. The dichotomy of the woman looking downward opposes the nature of the blackbird’s will to hold the woman’s hair loosely upward, almost attempting to pull her away from her hunching posture. Mochimaru intended for the figure to be out of reality, almost somewhere else, and the birds represent the fantasy, but in this depiction, the woman lives in the delusion of a fantasy world while the birds help carry her into that fantasy world.

Colored Series

While the black-and-white series was a response to the themes that emerged through the literature and association to the people with Hikikomori through digital painting, the colored series responded to the black-and-white with a focus on the Mochimaru’s perspective and opinion of living in social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. The artist representations considered Japanese culture as one of the causes for Hikikomori and, therefore, considered her childlike self in these roles—in order to represent what it was like living in Japan as a child and concurrently as a college-age student in social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. The colored series emerged in six figurative digital color paintings and a color diptych.

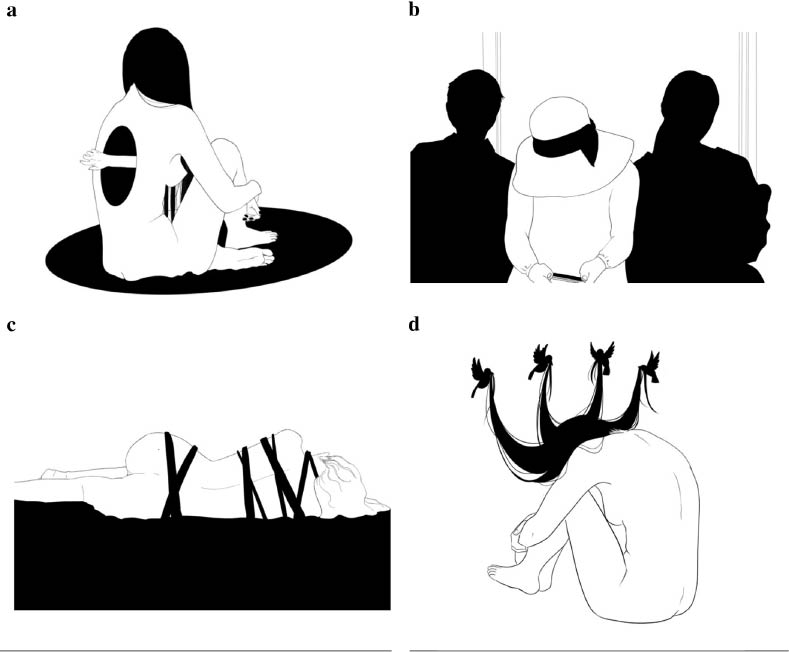

“Isolation「孤独」,” Figure 2a, left panel illustrates a naked female figure grasping hand mirrors in both hands and is gazing at herself at the right-handed mirror. Around the woman, there are four rectangular shapes painted with colorful vein-like lines that appear as walls enclosing her back, side, and floor. The yellow light comes from the top left corner of the illustration and becomes darker as the light descends to the bottom right corner. The woman’s expression is neutral, and her posture is tall. Her legs are crossed, and she appears to sit balanced in the center of the image. In solitude, the woman can only see her reflection, whether she looks to the right or the left, which Mochimaru considers to be a form of self-love, by taking time to focus on the self without being overly concerned with the view of the outside world.

FIGURE 2 | (a) “Isolation「孤独」,” and (b) “Expectation「期待」,” Digital color paintings by Yuri Mochimaru.

“Expectation「期待」,” Figure 2b, right panel, illustrates a human head, neck, and shoulder, with the nose and mouth section cut out. The head appears frail, ethereal, and almost paper-like, while the eyes are stark white and non-existent. Around the head, there are two hands grasping either side of the paper-like skull, splitting it down the middle. A contoured black pole is coming out of the inside middle of the head. Between the nose and the neck, a third hand, posing like a gun, points two fingers to the shattered tongue. The wrists of the three hands and the figure’s shoulders become blurred from the background. Mochimaru intended to represent the philosophical lack of disagreement, the Japanese culture of not saying “no” or “yes.” The tongue is broken because we cannot say anything and we do whatever we tell you—therefore the mouth is eliminated and thinking can become split.

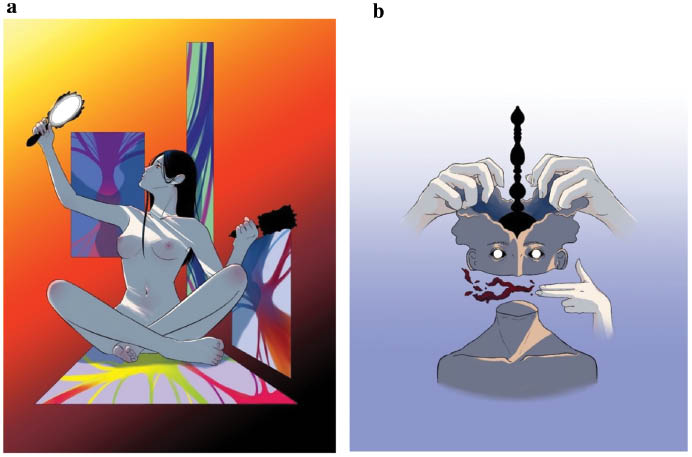

Figure 3 “Born Alone「独生」,” and Figure 4a, 4b, and 4c, “Die Alone「独死」,” “Come Alone「独来」,” and “Leave Alone「独去」,” respectively, illustrate a subseries of four images, two of which are part of a diptych all describing themes of aloneness. Figure 3 illustrates a blindfolded female figure encased in a clear membrane that she effortlessly appears to penetrate with her index finger. The blue gradient from the top right corner represents water, which the encompassed figure is floating within. The membrane is thin and transparent. Figure 4a, left panel, illustrates two stark-white human arms reaching toward each other—one arm stretching from the bottom of the frame and the other descending from the top. The fingers are stretched outward and appear to be in gentle movement, almost as if they are desiring for the hands to reach and grasp each other, across the green and yellow background, which represent dirt and earth. The arms appear to be identical in color and form, almost as if they are part of the same body. The bottom arm is cloaked in a pale-brown tree-bark-like wrap or tree trunk that becomes shredded at the forearm. Sunbeams emerge from the top left corner and cast sunbeams and shadows on the tree-covered arm. Figure 4b and 4c present a diptych illustrating a half-bodied female figure emerging out and into an arrow and tall black rectangle. Figure 4b, middle panel, shows half of the body of a female figure entering a black rectangle, and Figure 4c, right panel, illustrates the other half of the body emerging out of the black rectangle. The female figure’s affective response is flat, and she is wearing a long white shirt with her arms stretched as if in walking movement. There is purple gradient light emerging from the left side and illuminates the woman’s front. Mochimaru’s intent for the “Alone” illustrations were to present our come into and depart from this world, that although we are thrust together, we are all individual conscious beings uniquely alone as a single soul.

FIGURE 3 | “Born Alone「独生」”: Digital painting by Yuri Mochimaru.

FIGURE 4 | (a) “Die Alone「独死」,” (b) “Come Alone「独来」” and (c) “Leave Alone「独去」”: Digital paintings by Yuri Mochimaru.

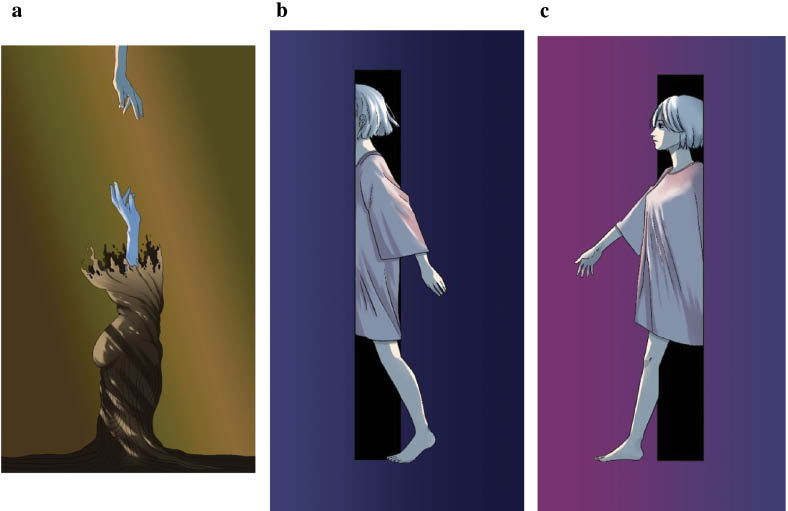

“Public Eyes「衆目」,” Figure 5a, left panel, is an illustration of a human “creature.” The face reveals only one eye and is covered by the red, yellow, and purple gradient cluster of mush with different-sized and colored eyes emerging from the surface. One white hand with fingers stretched in an awkward position hold the creature. In the middle of the facial surface, there is a straight beam of light. Mochimaru’s personal experience is reflected in these public eyes, as a youth feeling alone, with the world staring and judging. With the principle of “Wa” at play, she was to behave in a way that was polite, following directions, and keep herself in line while all eyes were watching, and judging.

FIGURE 5 | (a) “Public Eyes「衆目」” and (b) “Freedom「自由」,” Digital paintings by Yuri Mochimaru.

“Freedom「自由」,” Figure 5b, right panel, illustrates the head of an adolescent female. The figure was deliberately drawn with a more youthful intention that the other illustrations in the series. The head is floating in the middle of the illustration. Her gaze is directly into the eyes of the viewer, and she has a slight grin. The girl has white skin, and her face is cracked on a diagonal from her chin to her forehead. She has dark blue braided hair, and the end of the braids are untied with no band. Her head is flat, and a pool of water is accumulated in the flat space. There is a black egg in the water, with a white crack breaking down its middle. Mochimaru’s figure is about wearing a mask—the mask is cracked and her real face is underneath, but we cannot see it, there is just a crack revealed. The untied hair represents freedom, and the egg is cracking in the same vein as breaking the protective shell and letting in more light and freedom. The water gives a creative and playful space for the egg to be contained.

Discussion

This arts-based research came in response to hikikomori and the personal experience of living in isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Japanese people have common feelings on social isolation, and those feelings were inspired by the Japanese culture. Because Japanese people work to preserve harmony and cooperation within society through the philosophy of “Wa,” they tend to shun someone who creates dissonance. In Japanese culture, one way of creating dissonance is by not fitting in with society. When people do not fit into the harmony of society, they ultimately are forced to be isolated.

Mochimaru’s first impression of social isolation was identified in childhood while growing up in Japan. The view on isolation was negative, but by creating and expressing a digital art perspective on social isolation, the negative impression was changed. Like much of the world, Mochimaru experienced social withdrawal and isolation, almost being forced into Hikikomori. The pandemic gave many people a new perspective on social isolation, changing the definition of isolation from a negative view to something more positive—viewing isolation as a time when we can take care of ourselves and review our personal values.

In Japan, those diagnosed with Hikikomori become outcasts and are disregarded by society. The cycle of loneliness turns into a spiral of mental health issues with depression and anxiety. This research and its discoveries may contribute to the field of digital art therapy and bring awareness to mental health in Japan, whose members of the community are navigating their own social withdrawal. Digital art-making and digital art therapy can offer an easy and fast way to express my perspective on the topic of isolation. Because digital art-making does not require a lot of materials such as brushes or canvas, the artist can draw and create digital art anytime, anywhere without occupying much space. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the need to quarantine and isolate for one’s own health and wellness, the ease and accessibility of digital art may offer a meaningful tool for all people. The author’s hope is that this research will encourage creative expression, health, wellness, and meaningful engagement in society.

About the Authors

Yuri Mochimaru graduated from Endicott College in Beverly, MA, USA, with a BFA in art therapy in 2021. She completed her senior year thesis remotely and while socially isolated in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Yuri lives and works in Yokohama, Japan, where she is a 2D and 3D digital video game designer. Her website is yurimochimaru.com.

Krystal Demaine, PhD, is a board certified music therapist, registered expressive arts therapist, registered yoga teacher, professor of expressive therapies, and expressive therapies thesis advisor in the School of Visual and Performing Arts at Endicott College in Beverly, MA, USA. Her approach to the arts, teaching, therapy, and parenting are grounded in science, play, creativity, and the power of human connection. Her website is www.krystaldemaine.com. ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6737-4101.

References

Bedford, K., & Fukada, S. (2020). Okinawa: The island of the almost-eternal youth. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20201126-why-so-many-japanese-live-to-100 (accessed on 11 March, 2021).

Berman, C., & Chen, X. (2022). COVID threatens to bring a wave of hikikomori to America. Scientific American. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/covid-threatens-to-bring-a-wave-of-hikikomori-to-america/ (accessed on 20 April, 2022).

Berkman, L. F., & Syme, S. L. (1979). Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine-year follow-up of study of Alameda County residents. American Journal of Epidemiology, 109(2), 186–204.

Biordi, D., & Nicholson, N. R. (2008). Social isolation. In I. Lubkin & P. Larson (Eds.) Chronic Illness: Impact and Intervention (3rd). Boston, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning.

Cabinet Office. (2015). The truth of prolonged hikikomori. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/youth/whitepaper/r01gaiyou/pdf/b1_00_02.pdf (accessed on 11 January, 2021).

Darewych, O. H., Carlton, N. R., & Farrugie, K. W. (2015). Digital technology use in art therapy with adults with developmental disabilities. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 21, pp. 95–102.

Fujimoto, K. (2012). From an isolated society to a connected society: Social security reformbasedon social inclusion. Minerva, Japan: Minerva Shobo. Available online: https://www.minervashobo.co.jp/book/b103649.html (accessed on 21 November 2020).

Gavin, J., & Brosnan, M. (2022). The relationship between hikikomori risk and internet use during COVID-19 restrictions. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 25, 189–193. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2021.0171.

Hasegawa, K. (2006, July 15). Japan here and now. Hirigawa Times. Available online: https://hiraganatimes.com/web/categories/5 (accessed on 20 November 2020).

Hayashi, S. (2008). The culture of “Wa” and the culture of “Sa”: Considerations from the point of Japanese circumstances. Studies in Comparative Culture, 82, 81–92.

Ito, R. (2014). A study on art therapy and art education. Human Relations Research, 13, 139–152.

Jamerson, J. L. (2018). Expressive remix therapy. Using digital media art in therapeutic group sessions with children and adolescents. Creative Nursing: A Journal of Values, Issues, Experience, and Collaboration, 24(1), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1891/1078-4535.19.4.182.

Koshi, M., & Aoki, K. (2017). How do young adults with Hikikomoro intend to change themselves? Japanese Journal of Counseling Science, 50(2), 61–72.

Kimura, R. (2008). Japanese pragmatics in customer service—Discourse analysis by role-playing Chinese and Korean students. Yamaguchi University Faculty of Humanities Japanese Language and Literature Society, (31), 74–82.

Klinenberg, E. (2016). Social isolation, loneliness, and living alone: identifying the risks for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 106, 786–787.

Malchiodi, C. A. (2013). Art therapy and health care. Gilford Publications.

Malchiodi, C. A. (2018). Introduction to art therapy and digital technology. In C. A. Malchiodi (Ed.). The Handbook of Art Therapy and Digital Technology. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishing.

Matthews, T., Danese, A., Wertz, J., Odgers, C. L., Ambler, A., Moffitt, T. E., & Arseneault, L. (2016). Social isolation, loneliness and depression in young adulthood: a behavioral genetic analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51, 339–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1178-7.

McNiff, S. (2000). Feature: Art therapists who are artists. Journal of Art Therapy, 3(2), 42.

Neavel, C., Watkins, C., & Chavez, B. (2022). Youth, social media, and telehealth: How COVID-19 changed our interactions. Pediatric Annals, 51(4). https://doi.org/10.3928/19382359-20220321-03.

Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. (2020). Latest information on Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Retrieved:// https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/newpage_00032.html.

Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Sidani, J. E., Whaite, E. O., Lin, L. Y., Rosen, D., Colditz, J. B., Radovic, A., & Miller, E. (2017). Social media use and perceived social isolation among young adults in the U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.010.

Shimoju, A. (2018). Supreme solitude. Gentosha. Available online: https://www.gentosha.co.jp/book/b11535.html (accessed on 17 November 2020).

Stokes, A. C., Xie, W., Lundberg, D., Glei, D., & Weinstein, M. (2021). Loneliness, social isolation, and all-cause mortality in the United States. SSM-Mental Health, 1, 100014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100014.

Takahashi, D. (2020). Recent COVID-19 and hikikomori. NHK. News Web.

Teo, A. R., & Gaw, A. (2010). Hikikomori, a Japanese culture-bound syndrome of social withdrawal? A proposal for DSM-5. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 198, 444–449.

Teo, A. R. (2009). A new form of social withdrawal in Japan: A review of hikikomori. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 56, 178–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764008100629.

Teo, A. R. (2013). Social isolation associated with depression: a case report of hikikomori. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 59, 339–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764012437128.

Xu, K. (2009). Image comparison study of "Japanese culture" and "Chinese culture": Examination by Japanese mind map survey. Yamaguchi University Faculty of Humanities Japanese Language and Literature Society, (32), 136–150.

Zubala, A., Kennel, N., & Hackett, C. (2021). Art therapy in the digital world: An integrative review of current practice and future directions. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 595536. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.600070.