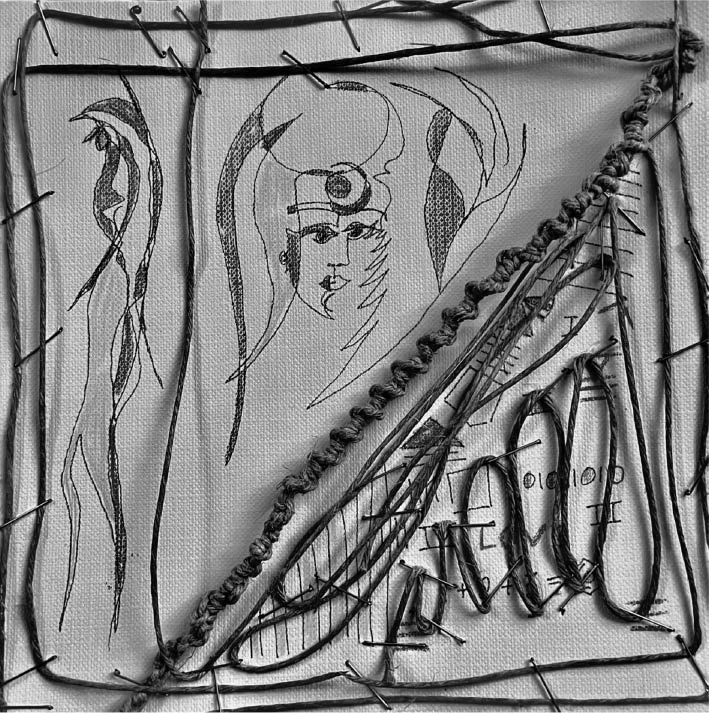

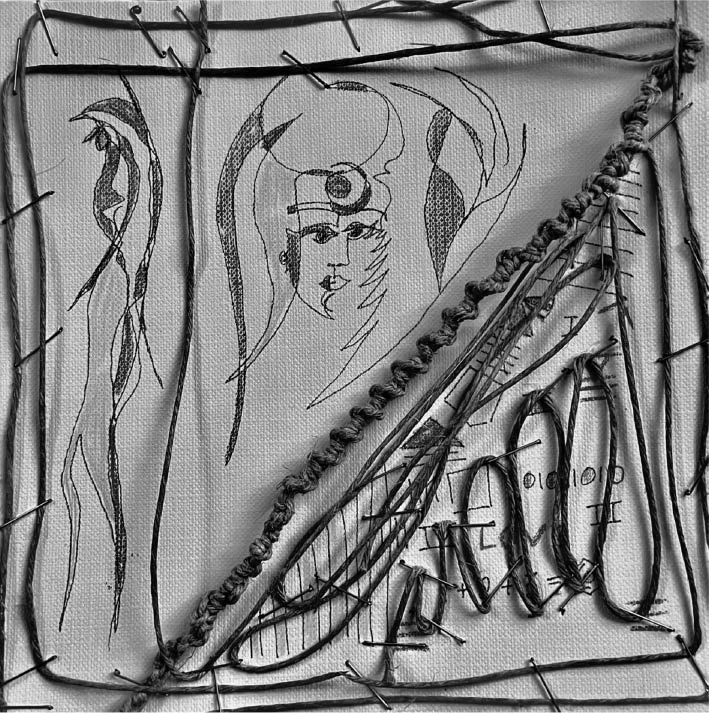

FIGURE 1 | Art created while writing this paper: Post-phenomenological art-based research and ancestral legacy influence on dealing with the pandemic.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2022) 8(1):113–125 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2022/8/14 |

Engaging with Doctoral Work during the Pandemic

在全球性疫情期间从事博士工作

Corcoran School of Arts and Design, the George Washington University, USA

Abstract

This article describes the acceleration toward digital conferencing that happened due to COVID-19 safety procedures as well as how one’s ancestral legacy of trauma could affect how one dealt with the arrival of the pandemic as a collective trauma. This paper describes the researcher’s experience in developing “embodied digital storytelling” as a post-phenomenological art-based research methodology as well as how the use of this methodology intertwined with the study of ancestral legacy and the arrival of a pandemic. The reader will follow the researcher’s experience in developing the methodology, finding her topic, and conducting her research during the pandemic. The article ends with an account of reclaiming a sense of belonging despite all the challenges discussed.

Keywords: embodied digital storytelling, ancestral legacy, collective trauma, COVID-19 pandemic.

摘要

本文描述了祖辈的创伤遗传如何影响一个人应对随着全球性疫情而来的集体创伤, 以及数字会议由于新冠肺炎 (COVID-19) 的安全措施加速发展。文章 描述了研究人员将“具身化数字叙事”发展为一种基于艺术的后现象学研究方法的经验, 以及如何使用这种方法与祖辈遗传和全球疫情来袭的研究紧密结合。读者将跟随研究人员了解她在全球疫情期间发展研究方法、发现课题并进行研究的经验。文末讲述了尽管历经所有文中提及的挑战, 重新获得一种归属感。

关键词: 具身化数字叙事、祖辈遗传、集体创伤、新冠肺炎 (COVID-19) 全球性疫情。

Introduction

Sometimes, research and historical events align. The arrival of a pandemic while conducting my research deepened and informed my dissertation: embodied digital storytelling (EDS) with ancestral legacy. On the one hand, my research embraced the new technology available to many, such as smartphones with powerful cameras, computers with film editing software, and the ability to connect via video conference. On the other hand, my topic of study was one’s ancestral legacy and how collective trauma, displacement, and loss could affect many generations’ descendants of survivors. COVID-19 seemed to intensify both a methodology that embraced technology and the topic of ancestral legacy that could support or handicap how one dealt with a life-threatening pandemic.

Method and Topic

COVID-19 accelerated the research process into a post-phenomenological arena, where the integration of technology in people’s lives became inevitable and the safest way to connect and co-create. Post-phenomenology is the idea that technology has become embedded into the human experience, and one can no longer research human experience without incorporating the digital world (Irwin, 2014). When COVID-19 came about, and everyone had to accelerate toward digital connection, I was already thinking in those terms, and I found that I had something to offer in the realm of digital storytelling. This digital connection was an integral part of my research method, which involved embodied relational inquiry and art-based research. This methodology came to me from an autoethnography art-based research, where I created a dance choreography as the basis of storytelling in film. You can see the storytelling and films developed before COVID-19 arrived, including the three embodied digital storytelling narratives created as a pilot study, on this link: https://giselleruzany.wixsite.com/website.

Pre-pandemic, digital storytelling was being used and seen as a research methodology with an anti-oppressive practice and nonhierarchical de-colonizing approach in collecting and analyzing data (Napoli, 2019; Cunsolo Willox, Harper, & Edge, 2013). For example, the participant needed to choose the story they wanted to tell versus what the researcher wanted to hear. Furthermore, because of its storytelling component, the respect for the land and the ancestors, and the collaborative aspect of the process, digital storytelling was also being considered as an indigenous research method (Cunsolo Willox et al., 2013). In general, digital storytelling has been described as a post-phenomenological approach to research because it combines the embodied experience of living infused with technology in one’s daily life (Irwin, 2014; Vacchelli, 2018), which during the pandemic became essential to all.

Furthermore, I would like to establish that this pandemic is a collective trauma, and ancestral legacy could affect how one deals with it (Bowers & Yehuda, 2016; Braga, Mello, & Fiks, 2012; Goodman & West-Olatunji, 2008). In this pandemic, I noticed that some people felt paralyzed and scared; others found themselves confident, resilient, and carrying on. The research showed that one’s ancestral legacy of trauma could influence one’s vulnerability to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Bowers & Yehuda, 2016). This vulnerability was observed and called transgenerational trauma (TGT) and was originated in 1996 to explain medical and psychological symptoms found in the offspring of Holocaust survivors (Braga et al., 2012). Nevertheless, there was a pocket of hope. Families developed resilience when they engaged with the arts and open communication (Braga et al., 2012). There was both an artistic element and a narrative in embodied digital storytelling, and therefore, qualities that promoted resilience.

A Post-phenomenological Art-based Research

In March of 2019, there was a sudden shift from a face-to-face interaction into a lockdown. This event sent everyone into an isolated space with a sense of uncertainty and loss of social support. At that time, I was investigating embodied inquiry as the basis to create choreography and was beginning to film it as a way to share the dance without the demands of live performance. I was, at the time, working as a dance professor adjunct faculty; I was seeing clients in private practice and working toward my PhD in expressive arts therapy. However, all these interactions shifted to be exclusively online.

Coincidently, I already had begun working toward a digital alternative, one that felt authentic, artistic, and transformative, as I needed to send my artistic inquiry to my professors in a digital format. I wanted a process of sharing that could be as engaging as live performance and could also help me heal my sense of loss and ancestral disruption. Collectively, the method of short dance films was already showing up through Tictok and Instagram formats, which were software platforms where people shared dance films. Therefore, before the pandemic, the collective dance world was already shifting toward a digital format, where the economic pressures of space and theater no longer were needed to share one’s dance. Since the work I was doing involved self-investigation in a digital format, the pandemic did not delay the process, and the process became useful beyond imaginable.

The methodology I was investigating entailed creating a dance choreography piece in relationship to an embodied inquiry in relation to a topic, which was then recorded in a place of support and then edited in a 2- to 4-minute short film. The last part of this methodology was to investigate what was the story that the body was expressing in the edited film and record the narrative as a storytelling voice-over. This methodology, which I call embodied digital storytelling, had a story narrated in relationship to the choreography created from an embodied inquiry. This embodied inquiry was based on following the body’s sensations as part of an embodied inquiry and research (Todres, 2007).

As an adjunct dance professor and guest artist at George Washington University at that time, I suddenly had to teach and create a dance without a dance studio. Everyone was stuck in their own homes, and we could only meet through video conferencing. I used the same methodology I was developing during my doctorate, which due to its hybrid format, was already supporting a certain digital integration. I worked with three dancers’ experiences of the shutdown who were suddenly no longer dancing with their peers in a studio and had to face the issues of a global pandemic. Here is a link to that work: https://youtu.be/LR8I-kDL3rU. I had a freshman student from Puerto Rico who never left home to go to the university, a sophomore who had to go back to live with her parents again, and a senior student that was isolated in her own apartment but not able to see anyone at the university. During the work, one dancer got COVID-19 and was absent for a while; then another could not find anyone to record her dance near the ocean, as we established would be a way to connect with one another. Then there was the sheer lack of space to move, lack of privacy, or knowing one another through a physical exchange. All these unknowns were heavy on a dancer’s experience, as dancers are known for being nonverbal, self-critical (especially on video), and needing a disciplined amount of dance classes in a large and empty space, most call home. COVID-19 was disruptive when it came to the life of a dancer. However, the EDS work seemed to provide a safe and creative methodology to explore resilience in a collective traumatic moment. These dancers showed me it was possible to do embodied and artistic inquiry during the pandemic.

For my research about ancestral legacy, I wanted to work with embodied dancers because I thought the years of self-investigation could give the research an authentic and honest embodied expertise. Looking for dance participants during COVID-19 meant that I needed to find dancers who felt interested in investigating their ancestry and had the emotional support to express their embodied inquiry while in a video conference, but technically alone. Some dancers felt fatigued and were experiencing migraines due to increased screen time and the fear of an unknown virus. I found that participants wanted to participate in the research for the promise of engaging with movement and dance again. Most felt stuck and uncreative, as most dancers lost their space and practice time during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As I began the work in meeting the participants, we all knew that we could not meet face to face and that the dance would be limited to their environment. At that time, many also were hoping to get out of a general malaise that came from not being able to share life and dance with others and not knowing when or if there would be a vaccine or cure to an air born virus that could kill or alter one’s life with prolonged symptoms. Therefore, my first obstacle was finding participants willing to engage with my research on top of all their angst, fear, losses, isolation, and the demand to continue with their jobs online and trying to keep up with the learning curve of technology. An interesting aspect of COVID-19 is that people I danced with, very long ago, were contacting me to ask what I was up to, which was very surprising. COVID-19 seemed to give many old friends the motivation to reconnect, and I was getting calls from dancers I had danced with whom I have not spoken with for more than 30 years from all over the world. People from England to Brazil were marveling that we had not tried to connect for so long and that now we had the technology to do so even if oceans apart. All dancers were home, suddenly thinking of their most important performances and embodied connections. We were reaching for one another, reminiscing about the past and remembering the HIV pandemic of the 1980s and how we supported one another in the past. Even though many people called me and showed interest in my research, many also felt overwhelmed by the perspective of doing any embodied investigation, afraid of uncovering more emotional pain they already were aware of within their bodies.

Through a snowballing sample that began from old contacts who showed up during the pandemic and new online connections during the PhD program, I ended up with six participants (plus myself) who had very different and complex multicultural histories and lived in the East Coast, Brazil, and India. Since the research was being done online, the location of the participants did not matter as much as looking into the time difference and COVID-19 stress. These participants expressed a desire to engage with an embodied inquiry as a way to move out of paralyzing isolation. Diamond and Shrira’s (2018) study reported that creativity had a moderate statistically significant correlation with resilience and growth with survivors of the Holocaust. Knowing that art brought resilience in times of collective trauma, I found confidence that what I was proposing could provide support and repair. Thus, I began my EDS with ancestral legacy in November 2019, when we still did not have a vaccine or an understanding of COVID-19.

An Equanimous Collective Trauma

Before COVID-19 hit, and I began my doctoral studies at Lesley University, I was already feeling an existential crisis. This feeling came from many areas: growing unfriendly sentiment toward non-White migrants in the United States, my father’s decision to no longer have me in his life after he survived cancer, which was followed by my parent’s divorce in Brazil, and my father’s sister, who lived in Israel, dying of cancer. As the world went into lockdown, my longing to be connected with my family increased. Since I was no longer seeing clients face to face, I used the same EDS methodology to investigate my new reality. You can see that investigation on the following link: https://youtu.be/0sdcOZRhMq8.

I wanted to know why and how this ancestral ancient history was still present in my body even when disconnected from my family. The research showed me how TGT could show up as an avoidant attachment, a sense of rootlessness, or lack of place attachment (Braga et al., 2012; Felsen, 2018). Early research already pointed to the fact that ancestral legacy could affect one’s attachment styles, which could also be seen as TGT (Bar-On et al., 1998; Felsen, 2018; Wallin, 2007). Nothing began with me, but in the history of who came before me (Wolynn, 2017). I thought this was what I was going through, and began dancing about that, which seemed to help me find words about how I was feeling. The more I was able to tell the stories of my ancestors, the more it made sense why I felt so vulnerable and alone.

Before the pandemic hit, I was already feeling the effects of the pandemic of tribalism, where being different was grounds for exile, outcasting, and boycott. I felt like there was no safe home for me, and as I investigated my surroundings, there was no safe home for generations before and after me. COVID-19 seemed to make the world also feel these feelings of exile and loss. The pandemic also illuminated to everyone the racial and economic tensions that were present all along. The pandemic forced everyone to face the consequences of collective trauma, no matter the race, the riches, the country, we were all in it, and the demand for equanimity was suddenly clear to most. The issue of transgenerational resilience and building a sense of home became an emergency to me and the whole world.

The research showed that second and third generations of trauma survivors could inherit a spectrum of experiences ranging from resilience to TGT (Braga et al., 2012). Research showed that TGT increased vulnerability in acquiring PTSD and psychopathology when exposed to life-threatening situations (Braga et al., 2012; Lehrner & Yehuda, 2018; Yehuda, Halligan, & Bierer, 2001). Studies also showed that TGT was present in the body as somatic symptoms or implicit memory when individuals knew without being verbally told that their parents were survivors of trauma (Baum, 2013). Nevertheless, when the story told was of what happened during a collective trauma, and it was a story of resilience and survival, then there was a shift toward mobilization to overcome one’s own losses as well as of one’s community (Goodman & West-Olatunji, 2008). As I studied my ancestral legacy, I found dances within my body that had a sense of understanding of the collective traumas that my ancestors went through. Many scholars recommended dance as a method to support the healing of TGT and as a form to access implicit memory (Baum, 2013; Buonagurio, 2020). Therefore, I searched for a method that could heal my ancestral legacy of traumas.

Dancing with an ancestor in the middle of a pandemic was not for the faint of heart, and not the easiest endeavor. The first part was by far the most difficult and emotional part where one had to find the courage to listen to their body’s emotional response when thinking of an ancestor who no longer was alive to offer their support. This meant dealing with the pain present in the heart, the knots in the stomach, and the burden felt in the shoulders while experimenting in a video conference. This embodied inquiry through movement was the foundation of the choreography, but it was emotional for everyone who engaged with it. The dance was a dialog in search for repair and understanding of how this ancestor impacted one’s present emotional state and allowed that emotional sensation to be expressed through dance. I found that this process could create a sense of inner witness and compassion and therefore offer assistance and support in these difficult times.

Studies showed that embodied and somatic responses to trauma included body memory, somatic vigilance, and withdrawal or alienation from the body (Johnson, 2009). Therefore, trauma treatment requires embodied work and validation of implicit memory (West, Liang, & Spinazzola, 2017). Furthermore, embodied inquiry in relationship to a trauma could facilitate healing (Brom et al., 2017). Another study showed that reconnecting to the unspoken story of the body could help make sense of trauma (Federman, Band-Winterstein, & Sterenfeld, 2016). When it came to dancing a dialogue with ancestors, and all the emotions that came up with that, gestalt therapy researchers and experts showed that embodied emotional expression facilitated completing unfinished business with the parents (Clemmens, 2019; Greenberg & Malcolm, 2002), so why not grandparents and beyond? Before the pandemic, in one EDS, I danced with my maternal grandfather and felt his lineage behind him, the Brazilian indigenous lineage and his ancestral sense of strength. You can see this exploration at https://youtu.be/eKj-KbfMsiY. Therefore, this embodied dance with one’s ancestor connected to previous studies that showed how embodied inquiry naturally lent itself to understanding collective trauma and potential for resilience, including toward systemic oppression and the present pandemic (Johnson, 2009; Snowber, 2020).

At the time of my doctoral studies, the Black Lives Matter movement was taking place two blocks away from my office at the capital, in Washington, DC, and inequality was being exposed as part of one’s lineage. This awareness was not unfamiliar to me, as my mother identifies herself as Afro-Brazilian and would often speak of racism. Furthermore, the pandemic exposed how some people had the privilege to stay home and work while others did not, and this difference was being correlated to a racially divided country. The pandemic was really talking about ancestral DNA and animosity toward minorities. Therefore, the COVID-19 pandemic, in a way, included not only the fear of an unknown virus, but fear of exile and oppression. The shift into lockdown could not be separated from threats and violence that came about toward Blacks, Browns, Asians, and Jews. Therefore, the body was only one of the areas where the pandemic was threatening. The pandemic illuminated embodied, ancestral, relational, cultural, political, economic, and environmental components in our collective experience facing the threat of COVID-19.

Similarly, a second level of ancestral legacy is one of ancestral land and loss of cultural connection to the environment in second and third generations of displaced families. The relational choreography with one’s ancestor was an internal intuitive embodied exploration. Nevertheless, it did not yet take one’s environment into consideration. I wanted to provide a process that felt transformative and grounded into a supportive space. By taking the choreography to a supportive space, I was looking to find safety, healing, and repair. The dance could begin to shift from an internal place to an environment of support. When it came to ancestral legacy and supportive environment, many studies showed that ancestral displacement affected the children and grandchildren’s place attachment (Bogaç, 2009). The new land, when it offered opportunities and environmental support, created healing (Scannell & Gifford, 2017). Furthermore, research showed that a resilient story of one’s ancestral loss of home and collective trauma could affect the resilience in the next generation (Goodman & West-Olatunji, 2008). Also, embodied research, art, and digital storytelling with migrants could facilitate a sense of home and belonging (Kale, 2019; Lenette, Brough, Schweitzer, Correa-Velez, Murray, & Vromans, 2019; Vacchelli, 2018). Therefore, there was a possibility that place attachment could be developed when one danced in the right space.

In my research during the pandemic, it was hard to find a way to create these conditions to heal one’s place attachment. Many participants did not feel safe to travel or go outside, so the place that they chose to record their choreography was mostly indoors, isolated or outside while wearing a mask. Taking the risk to take the dance into space was an activist process, claiming the space. The recording of it became a protest of one’s loss, one’s multi-generational history of surviving. The new space became another level of relationship to the embodied relational dance choreography. A sense that one’s ancestral lineage mattered and that the body felt the story within. By doing that, there was a revisit of the material but from the perspective of environmental support. Creating a site-specific work or installing a choreography in the environment was an artistic process as well as a transformative one. Using a camera created an invisible witness that felt like a second relational aspect of this process. Creating dual attention to the camera and the environment as well as the internal body awareness of the choreographic material created before was in a way a form of trauma rework and repair. Being out in empty streets, trapped indoors, or within empty public buildings, there was an eerie recording of a lockdown. You may see an EDS with my paternal grandmother in my empty office building hallway at this link: https://youtu.be/mmn2JL6zuVY. Here I remembered my grandmother’s journey out of Poland via England and arrival in 1939 after 6 months in a ship to Rio de Janeiro, the same year when the Nazi took her town and family.

Once the recording material was edited, it was time to facilitate the storytelling part of the embodied digital storytelling. In general, storytelling was still a personal protest, speaking the embodied truth, breaking family secrets and cultural and antiquated oppressive beliefs. I was introduced to storytelling as a research methodology in my doctoral studies, in arts and apprenticeship class. Kossak (2015) emphasized how entering a topic through art-based research, one could find the underlining embodied knowledge through a sense of attunement to the material. I began to understand that I wanted to find the words that my body DNA stories were telling me through nonverbal sensations. As I studied storytelling, a new expressive process started to develop through an art-based research. In art-based research, there is a natural dive in the uncertainty of the outcome; there is an intuitive sense of understanding and a down-up approach to knowledge (Rappaport, 2013). Through this approach, a sense of belonging started to surface within me. Meanwhile, many facing COVID-19 were just beginning to fear their surroundings as shootings and violence began to appear in synagogues and Asian-owned businesses. By using storytelling within my expressive art therapy repertoire, I was engaging with a powerful modality of narrative that came from an embodied place and therefore inherited empowering for one’s identity and culture. The use of storytelling in arts-based research provides a rework of one’s identity when it is grounded on an embodied artistic inquiry (Schwartz et al., 2020). Therefore, storytelling could help someone work through what happened while creating a positive sense of self-worth. In this way, my participants drew parallels of their ancestral survival with their own struggles during the pandemic.

When it came to collective trauma, such as the one we were going through during the COVID-19 pandemic, studies on resilience showed that survivors of the Holocaust were able to work through what happened through art, communication, and open, loving, humorous interaction; “humor at home, imaginary resources, and social support” (Braga et al., 2012). Braga et al.’s (2012) study provided the motivation to dive into art-based research that would allow these elements to be developed as we were living through the present collective trauma. Furthermore, Giladi and Bell’s (2013) study found that resilience was associated with individuals who had open communication and good differentiation within the family. Since TGT and resilience began within one’s family, the idea of dancing with an ancestor facilitated these elements. Another element that came working with ancestors was that it was evident that looking at the ancestor while living through a pandemic gave the participants and me the opportunity to see them from a lens of compassion. Most ancestors had lived through their own collective trauma that included migration, persecution, poverty, and other pandemics, including the Spanish flu, which seemed very similar to what we were living now. Therefore, the research on dancing with the ancestor was in way research on resilience on surviving other collective traumas. The recalling of one’s ancestral story of survivor showed that it could help one transcend the present collective trauma (Goodman & West-Olatunji, 2008; Walkerdine, Olsvold, & Rudberg, 2013). By studying past collective trauma research, it seemed that storytelling and artistic inquiry could aid not only the individual but the collective. This seemed even more pertinent when the collective trauma was not limited to one group or area and did not spare anyone.

A Sense of Belonging

As I coded my research, the data made sense to me on many levels. I found that ancestral trauma could manifest as a disruption of one’s sense of belonging, identity, and sense of self. The process of transformation in the dance was possible because of one’s imaginary resources to create the conditions to repair one’s embodied sense of ancestral disruption. In storytelling as in indigenous research, the story was about reclaiming one’s culture and beliefs and not what the colonizing and oppressive view imposed (Brown & Strega, 2005). Suddenly, imposed shame of one’s ancestry was overcome by love and gratitude. This process was possible by exploring a new perspective of what happened in the previous generations. In storytelling as research with survivors of 9/11 (Richardson, 2015), refugees (Lenette et al., 2019), and first nation (Cunsolo Willox et al., 2013), storytelling seemed to provide support to heal the embodied experience of these collective traumas. By sharing the stories as a group, there was a sense of social and cultural support as well as collective healing.

No longer feeling alone, I found myself part of many stories, and could see others, with the same deep and historical understanding. The more EDS processes I engaged or facilitated, the more I felt connected to the collective. I arrived at digital storytelling in this organic way; however, it was surprising to me to know that digital storytelling was being used as a research methodology for researching the experiences of refugees, migrants, and first nation tribes (Lenette et al., 2019; Vachelli, 2018; Cunsolo Willox et al., 2013). In EDS, there was an opportunity for someone to share their ancestral connection through dance and storytelling in an artistic short film, thus, creating a possibility for collective healing. When the participants came together to watch each other’s film, COVID-19 was especially heavy in Brazil and India, and it was obvious that the participants living in North America had more resources. However, an artistic community was quickly formed while the group shared their EDS with each other. The shadow of the pandemic and disparities was an important part of my experience engaging with doctoral studies during the pandemic. This was also an opportunity for me to notice my privileges and ancestral wounds.

The timing of my doctoral studies during such a stressful moment deepened my research in many ways, but it also deepened my sense of belonging. First, I found myself in a deep self-investigation of healing and repair before the pandemic. When the pandemic locked down the world, others found themselves in a similar place of uncertainty and isolation. Now, many were forced into a moment of self-reflection. People could no longer connect with their parents, and they could not travel. They could not meet with friends and did not feel welcome around the community where everyone became suspicious of one another as a carrier of COVID-19. Even if a bit guilty, I must admit that I felt a relief to notice that I was no longer alone. Everyone now was dealing with feeling unwelcome due to how they looked, what they wore, how people behaved was being suddenly reviewed by everyone. As I began my dissertation, and many felt in the beginning of their despair of loss and fear, I was beginning to mend. Now I could offer the EDS process to others.

Through dancing in dialog with my ancestors, I was beginning to feel certain ancestral support, a sense of history and a sense of survival and strength. I was beginning to find a certain understanding of what it meant to allow my body to speak and move in relationship to people who came before me. When it comes to finding how one is experiencing a pandemic, the methodology I engaged provided me a bottom-up approach, which helped me locate myself and understand where I fit in the history of my families, cultures, lands, and historical time. I began to understand that I was looking for a sense of belonging that I could only find within. The EDS process gave me a methodology to work through my feelings and transform them into something I could share with others. Now during the pandemic, this method could assist others with this creative adjustment.

I noticed that as an artist, the pandemic was another opportunity for me to engage with the creative process of diving into the pain and returning with art or an expressive piece. When I finished my doctoral study and no longer had my dissertation to work on, I felt a deep sense of sadness. So, I coaxed myself into creating a new EDS. Even though my doctoral studies were done, the pandemic was still going, and now it was being creative with a new variant called omicron. If I was going to get out of my grief, I needed to continue the work and keep looking for the resilient story, the compassioned inner witness, and the understanding that my sense of loss had to move into a sense of possibilities. I was surprised by the quick optimism I moved into; here is what I came up with: https://youtu.be/jpw3Sm7JiVs.

I discovered that through embodied inquiry, I found ancestral unfinished business, gratitude, resilience, and strength. Using the gestalt premise of embodied dialogue through an embodied dance, I found that my participants and I could repair and heal connections to ancestors who were no longer with us or who we did not even know about. By embodying an ancestor and dancing from different seats, there was a natural repair that connected with past research on gestalt chair embodied dialogue (Clemmens, 2019; Greenberg & Malcolm, 2002). The imaginary resource through embodied inquiry allowed a shift within where ancestral support and resilience was felt in the dance and the new narrative. Therefore, even during a collective lockdown, I found myself with a method I could engage with and find resilience, a sense of connection, and support. Finally, I am grateful to my ancestors, others that are willing to engage in the creative act, and the artistic community that is beginning to unfold and where I belong (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 | Art created while writing this paper: Post-phenomenological art-based research and ancestral legacy influence on dealing with the pandemic.

About the Author

Giselle Ruzany, PhD, LPC, is a psychotherapist in Washington, DC. She has an extensive background as a dancer, professor, choreographer, and art-based researcher. She has a master’s degree in somatic psychology with a concentration in dance/movement therapy, advanced post-graduate certifications in gestalt therapy and EMDR, and a PhD in expressive arts therapy. For more information, please visit www.gestaltdance.com.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; Tel: +1-703-395-7070, E-mail: giselleruzany@mc.com.

References

Bar-On, D., Eland, J., Kleber, R., Krell, R., Moore, Y., Sagi, A., Soriano, E., Suedfeld, P., van der Velden, P., & van IJzendoorn, M. (1998). Multigenerational perspectives and coping with the Holocaust experience: An attachment perspective for understanding the developmental sequelae of trauma across generations. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 22(2), 315–338.

Baum, R. (2013). Transgenerational trauma and repetition in the body: The groove of the wound. Body, Movement and Dance in Psychotherapy, 8(1), 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/17432979.2013.748976.

Bezo, B., & Maggi, S. (2015). Living in “survival mode”: Intergenerational transmission of trauma from the Holodomor genocide of 1932-1933 in Ukraine. Social Science & Medicine, 134, 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.009.

Bogaç, C. (2009). Place attachment in a foreign settlement. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(2), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.01.001.

Bowers, M. E., & Yehuda, R. (2016). Intergenerational transmission of stress in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology, 41(1), 232.

Braga, L. L., Mello, M. F., & Fiks, J. P. (2012). Transgenerational transmission of trauma and resilience: A qualitative study with Brazilian offspring of Holocaust survivors. BMC Psychiatry, 12(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-134.

Brom, D., Stokar, Y., Lawi, C., Nuriel-Porat, V., Ziv, Y., Lerner, K., & Ross, G. (2017). Somatic experiencing for posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled outcome study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 30, 304-312. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22189.

Brown, L. A., & Strega, S. (2005). Research as resistance: Critical, indigenous and anti-oppressive approaches. Canadian Scholars Press.

Buonagurio, N. (2020). The cycle continues: The effects of intergenerational trauma on the sense of self and the healing opportunities of dance/movement therapy: A literature review (Publication No. 10036170). Doctoral dissertation, Lesley University. ProQuest Dissertation and Theses Global.

Clemmens, M. (2019). Embodied relational gestalt: Theories and applications. Taylor & Francis.

Cunsolo Willox, A., Harper, S. L., & Edge, V. L., ‘My Word’: Storytelling and Digital Media Lab, & Rigolet Inuit Community Government. (2013). Storytelling in a digital age: Digital storytelling as an emerging narrative method for preserving and promoting indigenous oral wisdom. Qualitative Research, 13(2), 127–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112446105.

Diamond, S., & Shrira, A. (2018). Psychological vulnerability and resilience of Holocaust survivors engaged in creative art. Psychiatry Research, 264, 236–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.04.013.

Federman, D. J., Band-Winterstein, T., & Sterenfeld, G4. Z. (2016). The body as narrator: Body movement memory and the life stories of holocaust survivors. Journal of Loss & Trauma, 21(1), 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2015.1024559.

Felsen, I. (2018). Parental trauma and adult sibling relationships in Holocaust-survivor families. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 35(4), 433–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/pap0000196.

Goodman, R. D., & West-Olatunji, C. A. (2008). Transgenerational trauma and resilience: Improving mental health counseling for survivors of hurricane Katrina. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 30(2), 121–136.

Greenberg, L. S., & Malcolm, W. (2002). Resolving unfinished business: Relating process to outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(2), 406–416.

Irwin, S. O. (2014). Embodied being: Examining tool use in digital storytelling. Tamara Journal of Critical Organisation Inquiry; Warsaw, 12(2), 39–49.

Johnson, R. (2009). Oppression embodied: The intersecting dimensions of trauma, oppression, and somatic psychology. The USA Body Psychotherapy Journal, 8(1), 19–31.

Kale, A. (2019). Building attachments to places of settlement: A holistic approach to refugee well-being in Nelson, Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 65, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.101315.

Kossak, M. (2015). Attunement in expressive arts therapy: Toward an understanding of embodied empathy. Charles Thomas.

Lehrner, A., & Yehuda, R. (2018). Trauma across generations and paths to adaptation and resilience. Psychological Trauma—Theory Research Practice and Policy, 10(1), 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000302.

Lenette, C., Brough, M., Schweitzer, R. D., Correa-Velez, I., Murray, K., & Vromans, L. (2019). “Better than a pill”: Digital storytelling as a narrative process for refugee women. Media Practice & Education, 20(1), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741136.2018.1464740.

Napoli, M. (2019). Indigenous methodology: An ethical systems approach to arts based work with Native communities in the U.S. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 64, 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2019.05.006.

Rappaport, L. (2013). Trusting the felt sense in art-based research. In S. McNiff (Ed.), Art as research: Opportunities and challenges (pp. 201–208). Intellect.

Richardson, K. M. (2015). Sharing stories of the 9/11 experience: An exploratory study of the tribute walking tour program. Journal of Loss & Trauma, 20(1), 22–33.

Scannell, L., & Gifford, R. (2017). The experienced psychological benefits of place attachment. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 51, 256–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.04.001.

Schwartz, S., Lieblich, A., Speiser, V. M., Lakh, E., Cohen, T., Dushi, P., Gilad, A., & Vaisvaser, S. (2020). Life story and the arts: A didactic crossroad. Journal of Applied Arts & Health, 11(3), 315–328.

Snowber, C. (2020). Dancesong. Dance, Movement & Spiritualities, 7(1–2), 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1386/dmas_00014_1.

Todres, L. (2007). Embodied enquiry: Phenomenological touchstones for research, psychotherapy and spirituality. Springer.

Vacchelli, E. (2018). Embodied research in migration studies: Using creative and participatory approaches. Policy Press.

Wallin, D. J. (2007). Attachment in Psychotherapy. Guilford Press.

Walkerdine, V., Olsvold, A., & Rudberg, M. (2013). Researching embodiment and intergenerational trauma using the work of Davoine and Gaudilliere: History walked in the door. Subjectivity; London, 6(3), 272–297. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxyles.flo.org/10.1057/sub.2013.8.

West, J., Liang, B., & Spinazzola, J. (2017). Trauma sensitive yoga as a complementary treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: A qualitative descriptive analysis. International Journal of Stress Management, 24(2), 173–195. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000040.

Wolynn, M. (2017). It didn’t start with you: How inherited family trauma shapes who we are and how to end the cycle. Penguin.

Yehuda, R., Halligan, S. L., & Bierer, L. M. (2001). Relationship of parental trauma exposure and PTSD to PTSD, depressive and anxiety disorders in offspring. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 35(5), 261–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3956(01)00032-2.