FIGURE 1 | Drama For Life- Performing Democracy.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2022) 8(1):71–88 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2022/8/2 |

There Are No Silos When We Are All Suffering: Interviews and Reflections on Ubuntu and the Arts in South Africa during COVID-19

当我们都在受苦时, 没有人是孤岛:

COVID-19期间关于南非乌班图精神 (Ubuntu) 和艺术领域的采访与思考

1Lesley University, USA

2University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

In the midst of winter, I found there was, within me, an invincible summer. And that makes me happy. For it says that no matter how hard the world pushes against me, within me, there’s something stronger—something better, pushing right back.

寒冬时, 我发现自己内心有一个不可战胜的夏天。这让我感到非常喜悦。因为它告诉 我, 无论这世界如何向我施压, 在我体内都会有更强大--更美好的力量, 在与之抗衡。

阿尔伯特-加缪 (2021年)

Abstract

This article will draw upon some of the creative work being done in South Africa from March 2020 through December 2021, during the time of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) worldwide pandemic, by artists working across disciplines in education, community, health, and mental health. The authors had been located in Johannesburg, South Africa, in early 2020, when their stay was cut short by the spread of the COVID-19 virus and the worldwide border shutdowns that followed as they were recalled to the USA in March 2020. They have remained in communication and contact with their colleagues in South Africa, and this article is based upon these observations and interactions. This article will describe some of the initiatives and programs developed by artists in the country as well as by the faculty in the Drama for Life program at the University of the Witwatersrand and the Art Therapy program at the University of Johannesburg. These initiatives have been used toward survival and healing in this liminal space of the COVID-19 crises.

Keywords: COVID-19, arts, arts and health, arts and healing, Ubuntu, South Africa

摘要

本文将借鉴南非在2020年3月至2021年12月冠状病毒 (COVID-19) 全球性疫情期间所做的一些创造性工作。这些艺术家们在教育、社区、健康、心理健康等领域工作。作者们2020年初已位于南非约翰内斯堡,当时他们的逗留时间因 COVID-19 病毒的传播和随之而来的全球边境关闭而缩短, 他们于 2020 年 3 月被召回美国。他们一直与南非的同事保持沟通和联系, 而这篇文章正是基于这些观察和互动。本文将描述由该国艺术家以及金山大学的"生活戏剧"项目和约翰内斯堡大学美术治疗项目的教师们所发起的一些倡议和计划。身处COVID-19危机的临界空间, 这些倡议得以运用, 促进生存和疗愈。

关键词: COVID-19, 艺术, 艺术与健康, 艺术与疗愈, 乌班图精神 (Ubuntu), 南非

Introduction

Across the world, artists, artist educators, and artist therapists are learning new strategies to carry, to hold, and to live with suffering. In South Africa as well as globally, artists are finding new ways to work with our collective stories. This has involved learning new ways of facing the losses and still being able to remember and recognize that life is still beautiful so long as we are still breathing. It is a new variation of “losing our mind and coming back to our senses,” a saying attributed to psychologist Perls et al. (1951) which became a prevalent theme in the 1960s. We are discovering new ways of using the arts as medicine in the face of illness and health-care disparities. In the midst of all this, we are all learning new survival and resilience skills that can help us thrive, learn, grow, and heal, and ultimately, to transform. This article will explore some of the ways in which the arts and artists are responding to these issues within the South African context.

These times of not knowing can be quite unsettling where everything previously taken for granted is in upheaval. As artists, some of the questions being asked include how can we continue to survive when funding is cut, and how, as therapists and care givers, can we heal others when we too are suffering? This article will share some of the innovative ways that some of these South African creative artists, educators, therapists, and community workers have broken down barriers across the digital and social divides and have entered into creative new collaborations with community partners and other stakeholders to continue to serve their communities in these times of considerable duress. The worldwide pandemic has created a breakdown in the ways in which the arts have operated in the private and public sectors, within cultural, educational, community health, and mental health systems. Furthermore, systemic inequalities across all of these sectors have exacerbated accessibility issues. This article will describe some creative approaches to adapting existing resources across the digital divides to reach across personal, community, local, national, and international issues and boundaries.

Days of Rage in South Africa in July 2021

In South Africa, the current times are influenced by many factors, including the legacy of decolonization, the unresolved issues of governmental corruption and incompetence, health disparities and inequities, food and medical access and supply shortages, homelessness, criminality, and overwhelming unemployment and poverty. In the backdrop to all of this is the ever-looming presence of the COVID-19 pandemic, leading toward a new layer of collective traumatization and re-traumatization. The virus does not discriminate, and everyone is affected by its ravages and consequences. As mentioned previously, the social and economic disparities in South Africa are enormous and have become exacerbated during this time. On top of all of this, recently, the “days of rage”—rioting, burning, and looting following the incarceration of former President Zuma in July 2021, has left the country shaken to its core. Fogel (2021, n.p.) wrote: “South Africa is not a normal country. Almost half of the labor force is unemployed; the number rises to 76 percent for young people, who have no hope for their future. South Africa has the highest inequality rate in the world, with extreme wealth living next to extreme poverty. It is a country in which violence, state dysfunction, and broken services are normal.”

We interviewed Hamish Neill, a member of the Drama for Life faculty at the University of the Witwatersrand in August 12, 2021. He reflects back on the days of rage and reckoning in South Africa and talks about feeling that the country is sitting on a “ticking time bomb” where the level of social upheaval can quickly ignite an almost unnamed, unidentified influence which could be thought of as a third force. He has noticed that the news had become a form of extreme storytelling that feels almost frightening and disturbing. Reporters seemed at a loss for words, communities had barricaded themselves in, determined to protect themselves with live ammunition. Looting was rampant as mobs destroyed shopping centers, and broken glass littered streets and neighborhoods. At the time of this interview, when the violence was subsiding, so too were COVID-19 restrictions. He compares this moment in time to living in a pressure cooker where the accumulated and accumulating “steam blows up and simmers down.” He continued with:

A final aspect to consider is what happened most recently with the insurrection we had a couple of weeks ago. A number of our students were in fairly close proximity to the violence due to there being a study break and having travelled home. A major concern here is the “back-to-business” approach that government and millions have opted for. It is a grave concern.

Yet shortly after the rioting and looting subsided, communities banded together to clean up the destruction. South African poet Finuala Dowling (2021) captured this resilient response when she wrote:

(Still) Lovely Beyond All Singing

After fire and plunder, another sound:

bristles raking broken ground.

Amidst the trash and waste and weeping,

the age old fortitude of people sweeping.

The paradox of deep disparities and inequalities existing alongside equally deep capacities for resilience seems to be a part of the cultural conditions in South Africa. We interviewed Rozanne Myburgh, an art therapy staff member at the University of Johannesburg, on August 21, 2021. She highlights both the problems she encounters in her work and the creative ways of finding solutions and approaches for working with these. She describes the impact of the situation on the children and families at an agency she works at, Lefika La Phodiso Community Art Counseling and Training Institute. This inner-city arts-based program works in the communities that have been hard hit by the shutdowns, which resulted in loss of income, food shortages, limited access to health services, as well as the impossibility of parents being able to pay for their children’s school fees. In the reality of living in these inner-city conditions in Johannesburg, limited digital and computer access coupled with load shedding electricity restrictions renders digital programming inaccessible. To be able to work with children and families, the agency was required to operate in-person programing in relationship to shifting COVID-19 restrictions. Within these circumstances, she questions the meaning of how to provide “safe space” for children when there is no safety in general. During the “days of rioting,” some of the children she worked with spoke about participating in the looting and justified their actions based upon their mothers having lost their jobs and needing food and other commodities necessary for their survival. It became clear that a lot of the anxiety the children were feeling was based on food shortages and “you can’t work or do arts with a starving kid.” The agency quickly adapted their services to this situation and worked with community partners to develop the Yellow Umbrella Project, which raised funds to feed children as a precondition to be able to work with art-based educational and therapeutic programming. The program developed a food bank distribution center and later branched out to include homework preparation as part of their services.

In the many iterations and phases of lockdown, Lefika La Phodiso programming displayed a creative adjustment to constant changes and found that they could not work without parental buy-in, so they started a monthly support group for parents as well as their on-going programming for children. With the shifting sanitary requirements of COVID-19, they found that many of their teenagers were willing to step up and started taking leadership roles as “volunteens” who began to assist with sanitizing, taking temperatures, and engaging in art activities with the younger children. In these many iterations of “not normal normalizing,” the center began to function as an alternative home, safety-building, and a food safety pantry for children and families.

Some of the many innovations that were introduced included the development of wraparound programs and an exploration of innovative partnerships that included finding ways to train people from the community to replicate programs at other sites. With 582 children in their database from the past year, the agency found itself working with staggering new numbers, 90–120 children a week, and were able to procure food donations from Afrika Harvest. There are more children trying to get into the program than COVID-19 restrictions could allow, yet despite it all, the agency, children, and families they serve are examples of what we see in South Africa as what we have begun to call “thriving in adversity.” Lefika La Phodiso demonstrates the importance of ways in which the arts resonate with the needs and fluctuations of the times and demonstrate in action how to become trusted community allies in the movement toward social activism and change.

Thriving in Adversity—Ubuntu in Action

In the midst of what can appear as “gloom and doom,” we find a resilience among many creative artists and programs such as Lefika La Phodiso, leading to the development of new ways of working and drawing on indigenous traditions and the process of creativity. Evolution and emergence are at work in the creative expressions that are emerging with new collaborations among artists, educators, therapists, community and health workers together creating a “tribe” of resonance. This in turn creates a unifying feel of collective resonance that breeds both individual and collective coherence and continuity. We are learning anew what it means to be a human being.

In South Africa, artists are taking the concept of Ubuntu to a whole new level, bringing common humanity to self and others. This deep immersion in the culture of Ubuntu has very much influenced our understanding of “belonging” in connection to places and people. This South African concept of Ubuntu allows us to consider our connection to others, embedded as we all are in the web of life. Well-being is considered more of a communal than an individual matter. Essentially, it means that I exist because you exist. South African human rights activist Archbishop Desmond Tutu (1999, p. 35), whose passing on December 26, 2021, united the country in collective grieving, offered a definition of Ubuntu: “A person with Ubuntu is open and available to others, affirming of others, does not feel threatened that others are able and good, based from a proper self-assurance that comes from knowing that he or she belongs in a greater whole and is diminished when others are humiliated or diminished, when others are tortured or oppressed.”

It is a total kind of Ubuntu that Archbishop Tutu himself personified and lived. That is an Ubuntu of mind, heart, feeling, emotions, reactions, all embodied together to say metaphorically, “I see you through all of this with the awareness and connectivity that we all have.” “I am because you are.” In many tangible and intangible ways, it feels like, in South Africa, the “muscle” of “it” has been trained. This kind of full-bodied Ubuntu, which can transcend the “Zoom” room of isolation, can hold any thought or emotion of connection. This kind of disciplined life and digital awareness transcends the silos of difference and indifference. Here lies a different kind of recognition of what is going on for all of us. We are re-minding and re-bodying ourselves into a larger sense of togetherness deriving from an Ubuntu sense of community interdependence—a larger sense of belonging. We are entering another kind of dimension that we can tap into. A liminal, in-between dimension in which the arts reside, that artists bring forward and make available to us.

In these times of not knowing, there is additionally a feeling of loss of control, as if we have lost control of “it,” of ourselves, of each other. We are brought face to face with the bedrock of our fears, strengths, and vulnerabilities. This shakes us to the core of who we are, and mental health issues escalate, which in turn triggers more fear and anxiety, and then this highlights any and all of the unresolved trauma we individually and collectively carry. More than ever, COVID-19 points to increasing vulnerability, to lack of predictability. It spotlights tendencies that already exist around security and insecurity, abundance and deprivations, chance and randomness. The successive waves of the pandemic in South Africa highlight the unpredictability of it all. It enhances the need for meaning making when meaning is not to be found. In the face of all this, the arts offer moments of coherence and meaning making and even an ability to hold that “unknown” space. In the face of all this, the power of the arts is magnified in these dire circumstances. Transformation begins to happen within the creative space of hope and change. Creating through the arts means operating in that in-between space of letting go of control and waiting impatiently (and patiently) for the emergence of form. The importance of artistic recognition, witnessing and holding processes are noted by Kapoor and Kaufman (2020, p. 5), who wrote: “Therefore, we propose that regularly engaging in some creative activity can be associated with improved well-being and coping during the pandemic.”

There are many such projects that already exist in South Africa as examples of ways the arts can be creatively engaged in both prior to as well as during the pandemic. The 2020 Art Therapy Honors Student Cohort (2021, p. 2) at the University of Johannesburg created a resource guide for parents and educators to work with children using found and homemade materials. The students wrote that this guidebook, titled Cultivating Hope Through Artmaking Under Lockdown, was created under the spirit of contributing toward finding conditions where “the world of hope opens up again, enlivening the energy of the spirit, and body.”

In a similar manner, in a recent webinar the artist, performer and activist Lebo Mashile (2021, n.p.) describes ways in which trauma is mapping itself. She describes this as the “stories on the ground” that have not yet been given shape or form. She speaks about the development of new pathways where artists might serve as guides in a process she describes as “learning and unlearning in the online space.” She believes that “This online space simultaneously encompasses processes of embodiment and disembodiment.” The stories that artists are telling in a multiplicity of art-forms are the gifts they are offering, and the power of these gifts reside in the capacities the arts have to hold and contain and ultimately to help share and transform difficult experiences.

Around the world, all of us are now in this new journey, with its new portals, its new challenges, and new ways of learning and knowing. South Africa is a country of deep Ubuntu, that is of deep connections where the arts are already deeply embedded within the people and culture. The move into digital space exacerbated the inequalities of people who do not have access and band width to connect, yet also opened the way for enabling new possibilities for social engagement and learning and new forms of calling, echoing, amplifying, and responding. The individual and the collective experience are interdependent, and healing environments through digital means have been created across the digital divides. The urge to heal persists despite the fragmentation of living separately through times of COVID. The energy balance of giving and receiving contributes toward this healing with others in the on-going flow of living, learning, surviving, and even sometimes thriving.

Teaching and Learning Across the Digital Divide

As communities, educational, health and mental health, and artistic institutions scrambled to try and find ways of continuing to function during the COVID-19 restrictions and shutdowns around the world, there was a move toward offering these services through digital means. As Peters et al. (2020, n.p.) point out:

Digital pedagogies are of course not neutral with respect to the kind of sociality they encourage. Since a core function of education has always been social and cultural formation, the question arises as to what kind of sociality is possible when students and their faculty only meet in the digital space.…Also important of course are the issues of inequalities of access and outcomes in the new pedagogic spaces, and how they might be mitigated both within and across nations.

Around the world, educators, community workers, and therapists have all moved into operating in the digital space. In many ways, this has become the new “normal.” We have crossed the digital divide and have continued to invent new creative forms—arts fairs, arts festivals, tele-health, tele-therapy, performances, and music-making calibrated together in separate Zoom rooms while we wait for the world to return to what will ultimately be a “new normal.” With the necessity for social isolation during periods of lockdowns, we have nonetheless continued to function and have invented new forms for Zoom ceremonial and communal events such as burials, funerals, graduations, and weddings. We have had to face the overwhelming realities of dealing with people dying through the use of communal rituals of grief through Zoom, Facetime, or WhatsApp—of losing our loved ones at a distance. Yet despite these stressful and heart-breaking circumstances, we hear one triumphant story after another and witness the emergence of something already present, already reliable and already healthy. Many of these initiatives contribute toward a larger transpersonal effort at work in the South African context—that is, the opening up to the collective resources and intelligence already at work and working toward community coherence. There is an element of humility and grace at work as the burdens of the disease and its ramifications are collectively carried. There is an unknown element in this dynamic of healing, carried along by creative innovations. There are openings of heart happening on individual and collective levels. There is a deeper, wider aspect of healing happening. This involves the development of sensory attunement capacities in listening and allowing in the moment for the expression of stories which is characteristic of the arts. It is the belief of the authors that the role of the arts in the navigation of the unknown that allows for the emergence of new forms of relating and communicating.

In South Africa, these technological platforms are unevenly distributed across socioeconomic and accessibility barriers and are being addressed by some in innovative ways. For example, our colleague Dr. Petro Janse van Vuuren, director of the Drama for Life program at the University of the Witwatersrand, talks about providing luncheon vouchers for students to eat in establishments with wi-fi access in order to gain access to online classes and events. In our interview with her on August 26, 2021, she observes that “the lack of digital access accelerated the need for academic institutions to critically re-examine everything, all of their pedagogical practices and approaches in order to work with the new technologies.” As well as having to learn how to teach and work collaboratively with students and peers from a digital distance, time parameters have also changed. Individual faculty members have to learn to “play” with technology, to manage how to teach and learn in intimate and sometimes tight spaces, found both inside and outside of the Zoom box. The move from face-to-face teaching and learning into the online space generated moments of loss and moments of gain. Of necessity, it evolved into finding indigenous ways of presenting and learning in academic and community spaces. Students in the digital platforms moved into the living areas of faculty and vice-versa. This actually had the effect of neutralizing the space into an unknown area of learning as these began to shift to where digital spaces could be accessed—sometimes in bedrooms, in cars, in restaurants, along with occasional shifts to on campus spaces. With the variability of digital access, and the prevalence of the digital divides, the power cuts—“load shedding”—that are endemic and common in South Africa, often mean that sometimes both faculty and students are unable to use their cameras on screen and teaching takes place in empty square boxes with people’s names or photos attached—or not. This results sometimes in diluted individual and communal voices and never really knowing when people are actually present and in hearing range. The ephemeral shifts and changes that happen in both online and face to face spaces are discernibly different and involve shifts in paradigm and the development of new pedagogical and sensory skills. The faculty in the Drama for Life program tell one compelling story after another of ways in which they operated way and above their capacities as instructors in order to help support their students, including raising and donating funds and goods, and at times, driving across town to deliver food and digital access funds to students in need.

In relationship to the movement to online teaching in the South African universities, Fataar (2020, n.p.) criticizes the educational system both prior to as well as during COVID. He writes that:

The COVID-19 pandemic simultaneously engages, intensifies and subverts existing educational inequity and iniquity. This begs the question of whether pedagogical imaginaries can emerge in pandemic times that gesture toward significant educational equity, virtue and dignity. Gesture is important. It is a sign that insists on, yet, resists the deadness of our time. It signifies life left in the educational body, the body hoping to be educated, always available for educational resurrection.

Fataar is deeply critical of the structural inequalities in the universities and continued: “Online education has rapidly come to authorize visions of a default educational life under the epidemic.…The most efficient institutions grafted their on-line offerings onto colonially and apartheid acquired privilege.”

It is the writers opinion that as the end of the academic year 2021 approaches and students and faculty move toward the semester break, it remains to be seen whether studies will return to in-person learning and whether the long-term effects and ramifications of teaching and learning practices can be better assessed.

Neill, theater director and staff at Drama for Life, interviewed in August 2021 talks about the stresses that both faculty and students have encountered. He said:

I have been thinking about what is ‘a need’ and what keeps coming to mind is space to process/debrief, both for staff and students. I am well aware that while many students have the necessary support structures to hold them through their studies, a number simply do not and unfortunately aren’t finding the internal mechanisms to stay grounded and make decisions that help them cope better. It goes without saying that while food security is one factor that has been a challenge, a more common occurrence is battling anxiety and panic. Some staff members are also battling similar levels of stress and anxiety but are silent on this point.

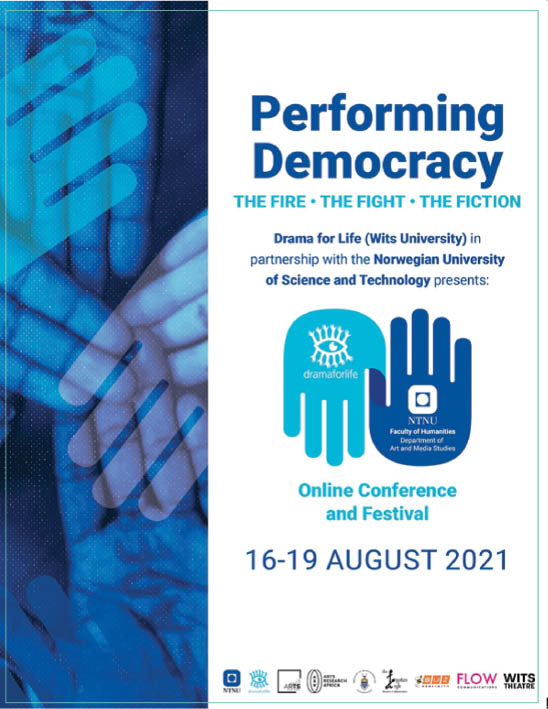

The Drama for Life (2021) program offered many supportive opportunities for students to engage in many kinds of on-going support groups, meeting both digitally and in person when COVID-19 restrictions allowed for on-campus gatherings. The program faculty and staff creatively responded to the needs and challenges with significant on-going programming and activities, events, radio shows, and even an online conference, titled “Performing Democracy.” This conference was described as a “breathing space” to breathe together with the intention of performing a democratic “moment of making visible the invisible, making the silence roar with voices.” The conference recording is accessible at: https://www.dramaforlife.co.za/events/the-drama-for-life-annual-conference-and-festival-during-covid-19 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 | Drama For Life- Performing Democracy.

Telling the Story through the Arts

The arts are a way of remembering, of carrying all of the stories, the faces, the lives, and the losses and still recognizing that life is still beautiful so long as we remain present in it and remain witness to ourselves and to others. This capacity of being in the moment offers an authentic sense of spirit and allows an access into the heart of Ubuntu. The moment is here and now in this present moment. Art allows a response with greater connectivity in the moment and has the ability to shape a new perspective. One that does not deny and respects the situation including when necessary, the horror. One that includes, holds, and allows us to find new ways of learning and being and adapting. The world is changing and is being formed by something we did not want or ask for, but allows us to move toward that which is broken in society, that which is creating violence and separation encompassing all injustices and disproportions. It allows for the opportunity of learning to be in wise relationship, to find our part in it and stay in deep connection to it. The richness of ancestral voices are being brought into play as part of an ethical process of restoration. This process involved the shaping of conversations moving forward, inviting others into the platform to join forces to restore “rightful place” in the world. This is creating a global mosaic of connection through the arts. This in turn involves a high level of competence building with the artists/educators/therapists involved in this effort, in turn creating collective competence in the community. Collective structures inherited from the past are not working, and the new competencies coming out of these creative initiatives are bringing ways of bridging difference and building coherence. Each of the artists we interviewed wove the threads of this tapestry of connection that evolved from conversations and events, forming a compassionate and respectful environment of action and reaction, infusing light and hope and building toward resilience. Learning from the culture of Ubuntu means seeing self and other, integrating a larger perspective of self and other, allowing for inspiration, awareness and moments of clarity, integration, and coherence, as evidenced in the contributions that each individual and group has made. There has been a reframing of what community means as community structures have been built out to encompass all student groups. There are channels of communication that are part of a larger whole including the individual, the social, the collective, and the ancestral as all part of a living system. Lineage of transgenerational experiences are carried and embodied and effect the intricate history living in each person. These remain in us as presences and collectively as unintegrated history as well as the resources of flow, strength, and resilience. All of these deeply embedded experiences are complex and intricately connected. Ancestral information and narrative, as these are shared in community, are the starting point that begins the process of clearing the collective wounding through presencing, that is by bringing these “stories” into the present moment. The more fragmented these stories remain, the less the development of collaborative skills and the more sharing of stories helps in being part of the dialogue of a creative healing process.

The transition from individual to collective healing is necessary to develop coherence and an ongoing collective story. Lederach (2005) has written about the importance of storytelling in community and how every individual carries within them their own narrative history which consists of their remembered history as it is lived in the past, present and future. Each individual carries the time frame experience of their own “100 year flesh and blood history,” that is the cumulative experiences of their parents, their grandparents and their ancestral history as time-framed encapsulated experiences attached to “flesh and blood.” He maintains that our survival as a species depends on finding place, voice and story, individually and collectively. He continued: “Telling the story allows for the restoring and restoration. This allows for the re-storing of the individual and of the collective. It allows for the re-negotiation of identity—away from the previous position allowing for the collective healing of all who hear, see and witness. This leads to prevention, social change and a vision for the future” (Lederach, 2005, p. 141).

Telling the story through the arts can be a ritualized and boundaried form that carries the potential to contain all and every aspect of the human experience. Telling the story can enable what cannot be otherwise said or done to be said and to be done. Narrating the story can serve as a meeting point between the individual and the collective, bringing them into a space beyond the boundaries of the self and others. In this space, all potentialities are accessible, in the continuity of collective wisdom across the generations. What is enacted is the heart of the matter (Marcow Speiser, 1998).

Engaging the creative process allows for a mobilization of resources (emotional, social, spiritual, physical, cognitive) The arts and expressive enactments are ways of “telling the story” in symbolic ways that are able to “hold and contain”—that is, to have coexisting within them complex and at times contradictory elements. The telling of stories and the expression of personal narratives through a wide variety of art forms to a community of witnesses can be a powerful tool for individuals to work through difficult experiences. The creative arts have demonstrated efficacy in working with trauma and in developing resilience (Johnson, 2009; Cohen et al., 2006; Byers, 1996). As both an educational and therapeutic tool, the arts allow individuals to express themselves from a deeply cultural perspective. This is particularly important in a context such as South Africa, where a participant may be operating in a second or third language. The arts allow for modes of communication other than those based in written or spoken language and thereby promote a wider spectrum of possibilities for communication. In the telling of stories, it is the writers hope that in the articulation in the present, the fragmentation of the past can lead toward developing new solutions. This can enable the shift from telling the stories from the perspective of the original individual heroic journey, toward building that capacity of telling collective and collaborative stories, which in turn builds uniquely toward an Ubuntu perspective.

Telling the Story Through the Arts from the South African Perspective

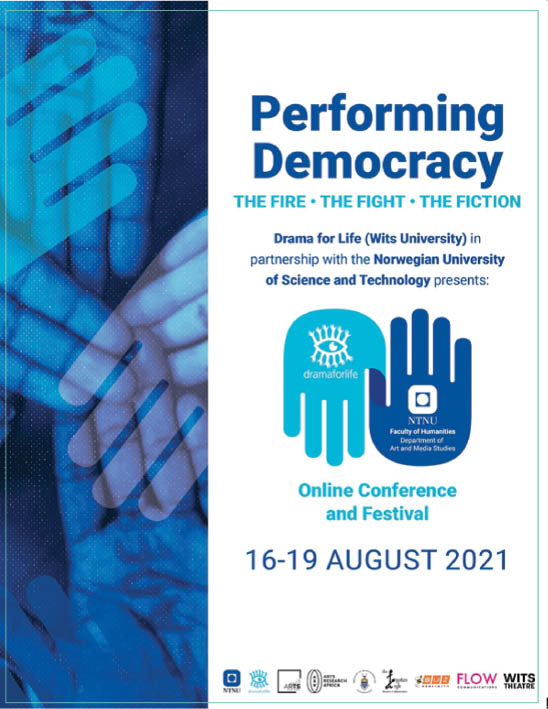

The story of artists and the arts in the South African context is one of both triumph and tragedy. The tragedy of COVID-19 has hit the artistic community in South Africa hard in terms of losses of individual lives to the disease as well as the closure of many artistic enterprises. Brown (2021) reports on the mismanagement of funds and artist protests in South Africa during the pandemic and writes that the “culture ministry is facing anger from the public for ineffectively supporting the arts during lockdown.” Throughout the pandemic, there have been sit-ins and demonstrations protesting the lack of support for artists and alleged theft of funds by the Department of Sports, Arts and Culture, funds that were to be allocated for the relief of artists. One such demonstration illustrated in the poster below was organized by Vuyani Dance Theatre (Figure 2). Throughout the pandemic, artists have stood together, continued to create, suffered together, protested together and banded together, to support, to gather, and to mourn.

FIGURE 2 | Vuyani Dance Theatre- Silent Protest.

In a recent Stand Together Arts Summit, held on September 27, 2021, Heywood (2021, n.p.) reported in the Daily Maverick publication that “South African artists have declared that their future is aligned with struggles for equality, transformation and social justice, and called for improved cooperation with the broader civil society heralding the transformative impact of the arts on society and nation-building.” The article continues:

In his opening plenary speech [https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-09-20-arts-in-south-africa-under-existential-threat-we-have-to-imagine-and-remake-our-society/], playwright Mike van Graan sketched a short history of the role of artists at previous moments of crisis, including in the struggle against apartheid, when faced with a different type of silencing and censoring. Today’s silencing arises from the shutting of theatres and other performance venues caused by Covid and is exacerbated by a prolonged and abject failure of the government to encourage and fund the arts.

The creative industries do not exist in a vacuum. The arts help people process the world around us. They play a vital social role. In Van Graan’s words: “We have a duty to help our fellow citizens make sense of this world, to interpret and reflect, to help our audiences to experience catharsis, to speak truth to power and somehow, somewhere, to find beauty, to affirm life. Even though we, too, are not well” (Heywood, 2021, n.p.).

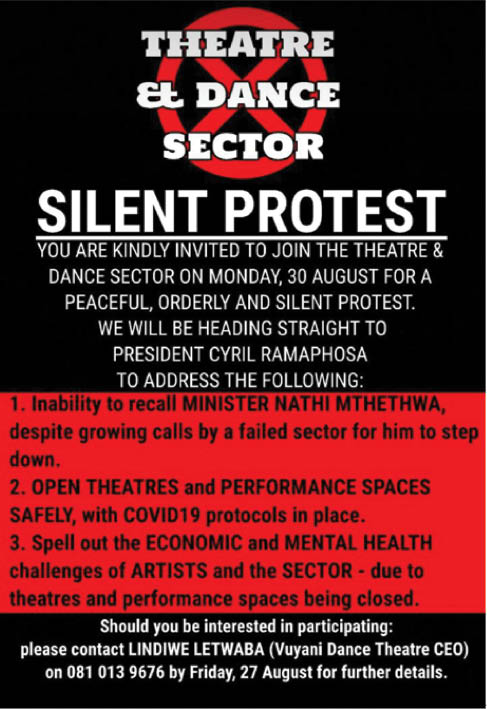

Ansell (2021) reports in an article in the New Frame how opera star Sibongile Mngoma was mishandled by police on November 2 and had her blouse torn from her body during a protest in Pretoria (Figure 3). The protest was held outside of the Department of Sports, Arts and Culture by members from the Im4theArts, a grass-roots organization working to uncover what had happened to the funding that was to be allocated to arts organizations. Ansell writes:

The protests began with a 60-day occupation of the National Arts Council’s premises in early March. The council, an entity of the department, was at that stage unable to answer multiple questions about the disbursement of a R300-million presidential economic stimulus package ostensibly intended to protect and grow creative livelihoods.

FIGURE 3 | Sibongile Mngoma- Protest in Pretoria.

These protests led to the creation of multiple state investigations. To this date, the reports have not yet been released by the authorities and funding has not been restored. The deterioration and ongoing deteriorating relationship within the artistic and creative sector and relevant authorities in the Department of Sports, Arts and Culture and other state agencies is an ominous sign in South Africa where the arts are so intrinsically necessary and indeed vital to post-COVID recovery and so essential to education, health, mental health, and public health.

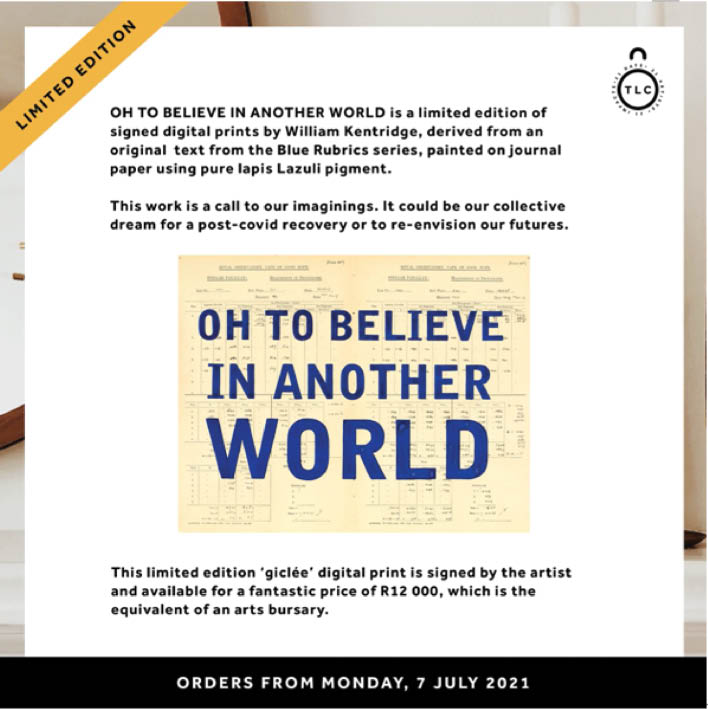

We interviewed Professor Kim Berman, founder of the first art therapy program in South Africa at the University of Johannesburg on August 4, 2021. She commented on the difficulties faced by the artistic community in South Africa during COVID-19. She paints a dire picture of a microcosm of arts in a slump, in that moment, particularly in the non-profit arts sector where the disappearance of relief funds through corruption and mismanagement have had severe effects. Many arts organizations have folded and artists themselves are suffering enormous losses. In her opinion: “The national arts funding has proved to be a debacle.” Berman speaks about the survival challenges facing the artistic community and its many losses. There have been many COVID-19-related deaths within this community, and many organizations have been forced to close. However, in the face of all of this, she believes that this is also where resilience kicks in and where innovation happens and where groups begin to band together and create new collaborations. She has undertaken such an innovative venture working together with a few print studios facing near closure, and working with the world renowned South African artist, William Kentridge (2021). Kentridge created a limited series print edition, titled Oh to Believe in Another World, as a fundraising initiative for these studios (Figure 4). Berman is the founder of Artists Proof Studio, which is a highly respected, long-standing art print making and training program in Johannesburg that was able to keep their doors open and continue their work during COVID.

FIGURE 4 | William Kentridge- Oh to Believe in Another World.

In a publication titled Cultivating Hope through Artmaking Under Lockdown, Berman (2021, n.p.) writes in the foreword that “The South African lockdown has been devastating for many, but particularly for children who cannot access the community centres where they found support, stimulation, and nourishment that builds confidence, self-worth and hope. Children who are not able to learn “online” and have their own creativity and play as their source for resilience.” Berman’s work offers a generative vision she holds about the future and the role that the arts continue to play toward building and sustaining future growth and development.

It is our understanding that the arts have helped to hold and inspire during COVID-19. In South Africa and elsewhere, they allow and build toward, hope, energy and innovation, and a different kind of well-being that nourishes the soul in a catalytic time. To move beyond COVID-19, we need to learn from some of these South African exemplars to build that capacity toward expression and health through collective healing processes. This includes teaching and learning the relational, sensory and embodiment skills that are cultivated through arts making both individually and collectively. This in turn leads toward a new and renewed creative skill building to face the present and future challenges that lie before us. Artists, community agencies, and therapeutic and educational institutions have the possibility of integrating what is being learned from teaching, learning and healing through the digital divides. There might emerge a re-imagining of possibilities for deep cultural shifts following the pandemic, drawing on ancestral knowledge, integrating compassion, wisdom, and a deep understanding of Ubuntu. We have learned anew that we are all connected and we are all in this together. In conclusion, it is our fervent hope that caring for each other, righting previous wrongs and injustices and caring for the planet will become the “new normal” as we move forward into the new possibilities that lie ahead, beyond the pandemic. In closing, we offer the words of Arundhati Roy (2020, n.p.):

Our minds are still racing back and forth, longing for a return to ‘normality’, trying to stitch our future to our past and refusing to acknowledge the rupture. But the rupture exists. And in the midst of this terrible despair, it offers us a chance to rethink the doomsday machine we have built for ourselves. Nothing could be worse than a return to normality. Historically, pandemics forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

About the Authors

Vivien Marcow Speiser, PhD, BC-DMT, LMHC, NCC, REAT, Professor Emerita, Lesley University, and Distinguished Research Associate, Drama for Life, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. Professor Marcow Speiser has directed and taught in programs across the USA and internationally and has used the arts as a way of communicating across borders and across cultures. She believes in the power of the arts to create the conditions for personal and social change and transformation. Her interests and expertise are in the areas of working with trauma and cross-cultural conflict resolution through the arts, and she has worked extensively with groups in the Middle East and in South Africa. Her contributions to the field have made her an international leader in dance and expressive therapy and earned her a Fulbright Scholar Award as well as a Salzburg Global Seminars Fellowship in 2020. She received an honorary JAAH Lifetime Achievement in Arts and Health Award in 2019, the 2014 Distinguished Fellows Award from the Global Alliance for Arts and Health, and a 2015 Honorary Lifetime Achievement Award from the Israeli Expressive and Creative Arts Therapy Association.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: vspeiser@lesley.edu.

Phillip Speiser, PhD, Research Associate, Drama for Life, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. Dr Speiser is an expressive arts educator/therapist, drama and music therapist, and psychodramatist who has developed and implemented integrated arts therapy and educational programs for children, adolescents, and families for over three decades. He is currently the director of Parkside Arts and Health Associates in Boston, MA. He has served as director at the Arbour Counseling Partial Hospitalization Program in Norwell, MA, and also the founding director of the Arts Therapy Department at Whittier Street Health Center, Boston, MA. He has worked and developed programs with individuals and groups in conflict around the globe, including South Africa and the Middle East. He is known in the Boston area for his ongoing commitment and work with violence prevention through the use of the arts. After 9/11, he developed and implemented arts-based “trauma recovery/prevention” programs in Boston and New York City. During the 1980s, he lived in Sweden and did pioneering work in the field of expressive arts therapy in Scandinavia.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: philspeiser@gmail.com; Tel.: +1 617-637-6617.

References

Ansell, G. (2021). State shows naked contempt for cultural workers. New Frame, Retrieved on December 5, 2021, from https://www.newframe.com/state-shows-naked-contempt-for-cultural-workers/?fbclid=IwAR2LiaKqj7nSFuKTC5ILSQ4GiDIvvi7UKxSnf2sxmszjkKlaOSqMI62Ru8E.

Art Therapy Honors Student Cohort. (2021). Cultivating hope through artmaking under lockdown. University of Johannesburg. Retrieved on November 9, 2021, from https://www.uj.ac.za/faculties/fada/visual-art/Documents/UJ%20Art%20Therapy_Resource%20book.pdf.

Berman, K. (2021). Cultivating hope through artmaking under lockdown. University of Johannesburg. Retrieved on November 9, 2021, from https://www.uj.ac.za/faculties/fada/visualart/Documents/UJ%20Art%20Therapy_Resource%20book.pdf.

Brown, K. (2021). Artists stage sit-ins to protest South Africa’s mismanagement of pandemic aid and ‘disappeared’ funds for the culture sector. Artnet News. Retrieved on Retrieved on November 9, 2021, from https://news.artnet.com/art-world/south-africa-funding-crisis-1956008.

Byers, J. (1996). Children of the stones: Art therapy interventions in the West Bank. Art Therapy Journal, 1, 238–243.

Camus, A. (2021). Albert Camus quotes. Goodreads. Retrieved on November 24, 2021, from https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/957894.Albert_Camus.

Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., & Deblinger, E. (2006). Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford.

Dowling, F. (2021). Finuala Dowling. Retrieved on November 14, 2021, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Finuala_Dowling.

Drama for Life and NTNU (2021). Performing democracy: The fire, the fight, the fiction? In 13th Annual Conference and Festival, University of the Witwatersrand, 16–19 August, 2021. Retrieved on November 16, 2021, from https://www.dramaforlife.co.za/events/the-drama-for-life-annual-conference-and-festival-during-covid-19.

Fataar, A. (2020). Educational transmogrification and exigent pedagogical imaginaries in pandemic times. In M. A. Peters, F. Rizvi, G. McCulloch, P. Gibbs, R. Gorur, M. Hong, Y. Hwang, L. Zipin, M. Brennan, S. Robertson, J. Quay, J. Malbon, et al., Reimagining the new pedagogical possibilities for universities post-Covid-19. Educational Philosophy and Theory (pp. 1–45).

Fogel, B. (2021). There is no silver lining to South Africa’s Zuma insurrection. JACOBIN, Retrieved on November 13, 2021, from https://jacobinmag.com/2021/07/JACOB-ZUMA-SOUTH-AFRICA-LOOTING-RIOTS-KWAZULU-NATAL.

Heywood, M. (2021). Covid-battered artists unite in call for stronger ties with civil society and the education sector. Daily Maverick, Retrieved on November 1, 2021, from https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-09-27-covid-battered-artists-unite-in-call-for-stronger-ties-with-civil-society-and-the-education-sector.

Johnson, D. R. (2009). Commentary: Examining underlying paradigms in the creative arts therapies of trauma. Arts in Psychotherapy, 36, 114–120.

Kapoor, H., & Kaufman, J. C. (2020). Meaning-making through creativity during COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 595990.

Kentridge, W. (2021). Oh to Believe in Another World. Artists Proof Studio. Retrieved on December 5, 2021, from https://artistproofstudio.co.za/products/oh-to-believe-in-another-world.

Lederach, J. P. (2005). The moral imagination: The art and soul of building peace. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marcow Speiser, V. (1998). The use of ritual in expressive therapy. In A. Robbins (Ed.), Therapeutic presence: Bridging expression and form. Bristol, PA: Jessica Kingsley.

Mashile, L. (2021). Unrehearsed futures #14, offerings of possibilities. In P. Vittal Rao, Blog, Unrehearsed futures S2, 8 July 2021. Retrieved on September 9, 2021, from https://dramaschoolmumbai.in/unrehearsed-futures-season-2-episode-14/.

Perls, F., Hefferline, R. E., & Goodman, P. (1951). Gestalt therapy verbatim. New York: Dell Publications.

Peters, M. A., Rizvi, F., McCulloch, G., Gibbs, P., Gorur, R., Hong, M., Hwang, Y., Zipin, L., Brennan, M., Robertson, S., Quay, J., Malbon, J., et al. (2020). Reimagining the new pedagogical possibilities for universities post-Covid-19. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 1–45.

Roy, A. (2020). Pandemic is a portal. Financial Times. Retrieved on November 9, 2021, from https://www.ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca.

Tutu, D. (1999). No Future without forgiveness. New York: Doubleday.