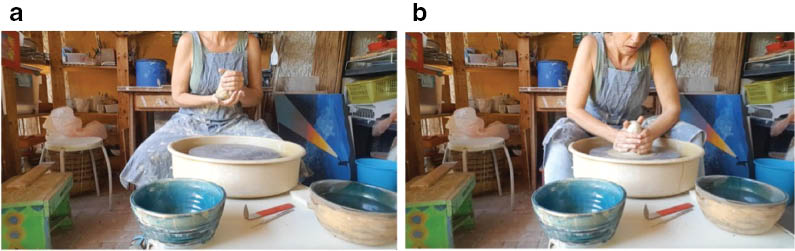

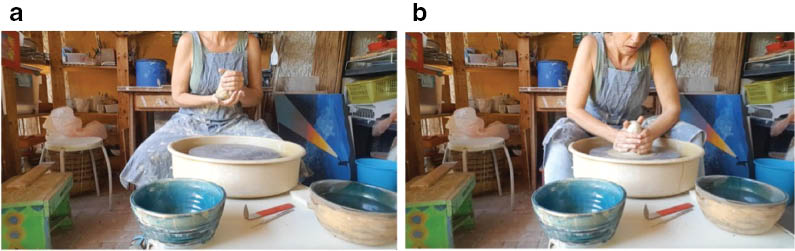

FIGURE 1 | (a) Aya, kneading clay in her studio. (b) Aya, centering the clay.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2022) 8(1):126–138 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2022/8/1 |

Artmaking Resilience: Reflections on Art-Based Research of Bereavement and Grief

艺术创作的复原力:对丧亲之痛基于艺术研究的反思

Ono Academic College–ASA, Kiryat Ono, Israel

Abstract

This article presents some of the elements of artmaking as sources of resilience within the process of bereavement and grief. It builds upon findings from an art-based research project conducted during the period of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic that explored properties of resilience in the face of sickness and death, which suggests three active elements to resilience: the capacity to observe pain, possession of faith, and the support circle. The article ties these findings, with other artistic projects in which artmaking responded to and alleviated sorrow and loss.

Keywords: bereavement, resilience, COVID-19, art-based research, arts and health, video art

摘要

本文介绍了一些艺术创作的元素,它们是历经丧亲之痛连接复原力的资源。这些发现始于2019 年冠状病毒全球性疫情期间进行的一项基于艺术的研究项目,探索了面对疾病和死亡时复原力的特性,表明了复原力的三个积极要素:观察痛苦的能力、拥有信心和支持圈。文章将这些发现与其它以艺术创作回应并减轻悲伤与丧失的艺术项目相整合。

关键词: 丧亲、复原力、新冠肺炎(COVID-19)、基于艺术的研究、艺术与健康、影像艺术

In memory of my friend Michal Aloni

The street is still today.

Winds of change mobilize stray grass

diverting my attention from emptiness

Words, compounded by letters,

pronounce my pain.

I drove by

your house

and all

remain.(Michal Lev, 2022)

Introduction

My dear friend, Michal Aloni, passed away two years ago. She passed away. Two years ago. We came out of her Shiva’a—a Jewish custom of mourning—on the day Israel announced social restrictions because of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, and life ceased to exist as I knew it. Ever since. I was given the opportunity to care for her during her last three months.

Nine of us, close friends and family members, circled her with our love and devotion throughout that delicate period. “How could wheat carry on growing?”, asked Tzameret and Barkani (1974) after the Yom Kippur War in Israel, and yet the country has robustly built itself and continues to do so, again. The imaginary line between life and death transpires in these turbulent times, reifies the questions of sustenance and nothingness, stamina and idleness, fragility, and resilience.

Shortly before Michal’s death, I was approached by two colleagues to guide them through the research they were undertaking exploring the sickness and death of their student who had passed away, and together with them, I conducted art-based research that explored the active elements of resilience in face of sickness and death (Lev, Kats, & Navoth, 2021).

During the year after Michal’s death, her eldest daughter, Romi, curated and scripted a short film for her high-school final project and invited me to participate as one of the lead actors. During that same year, Michal’s sister, Or-Li, became a ceramist, dedicating a section in her house to build a studio and to create. I find that these incidents are not accidental.

This paper presents thoughts about the elements of artmaking as sources of resilience within the process of bereavement and grief. It aims to offer a sustaining anchor in the face of threatening contemporary times.

Properties of Resilience

During the COVID-19 pandemic, I conducted with two colleague-researchers, Gili Navoth and Aya Kats, and nine student-co-researchers an art-based research that explored properties of resilience within a group of art therapy students in their master’s program, in the face of the sickness and death of their fellow student. We adopted Lahad’s definition (2017) for resilience as an ability to cope with crisis, stress, loss, and trauma. Within that research, we found three salient operative elements of resilience: observing pain, faith, and support circle. This paper builds upon the ripples of these findings.

Like others who define resilience as coping characteristics and/or adaptation to situations of vulnerability and adversity (Aburn, Gott, & Hoare, 2016; Li & Psarra, 2022), the circumstances of COVID-19 have indicated that resilience is expressed in physical and emotional health that occurs during or after injury and/or difficulty (Chmitorz et al., 2018). Creative projects, addressing the pandemic, which have risen globally demonstrate boldly that we all have the strengths and coping resources, which can be mobilized in times of stress.

The Capacity to Observe Pain as a Characteristic of Resilience

Our study germinated from an urge to be with and to process the agony and loss of a friend (Lev et al., 2021). My grief was commemorated by the losses of all participants in the research. We all shared a wish to bring up memories and look at our anguish. Expressions of participants’ ability to observe pain were seen in the pottery work of Aya. During our triangulated processing of the research material, she described her artmaking stages (Figure 1):

“I kneaded recycled clay that was raw, as we are. Watching footage of my process, I focused on my continued gaze towards the potter’s wheel. Pottery requires centering the clay, and yet, I experimented with releasing this concern and instead, letting it be—a crooked lump.”

FIGURE 1 | (a) Aya, kneading clay in her studio. (b) Aya, centering the clay.

Aya’s ability to sustain the imperfection echoed Gili’s description of being with illness in the classroom, defining it as a lump.

I have studied the ability to be with and observe carefully during my art-based research of intimacy (Lev, 2019). My fifth mode of inquiry was creating a video—ten to fifteen minutes long—for each participant in the research. The process of editing the video footage included multiple viewings of the video files produced during the co-researchers’ painting sessions, video footage from my response art to their sessions, photographs of the processes and artworks, the transcribed texts, and my journals. The careful examination of video footage included being intimate with the body of work, cropping the images, and organizing videotaped moments that seemed to echo ideas from the verbal discussions and response art sessions that addressed the research questions.

Similarly, the sixth mode of inquiry in our research about sickness and death (Lev et al., 2021) involved my creation and editing the video, In Sickness and Death—Final Video (Lev, 2020b). This inquiry mode was designed to extract significant evidence from the various research material and present the findings visually. It included meticulous selection within all types of data (transcripts, photographs, footage, and audios) to assemble elements that convey the results transparently and esthetically. Spending such valuable time with the video footage can be seen as an invitation to explore the subject deeply.

Similar to these modes of inquiry from the art-based research projects, Romi—Michal’s teenage daughter—watched the footage from her film repeatedly during the editing process and admitted to memorizing parts of her script until she was completely familiar with them. Sections that involve her mother’s words and demeanor were internalized and have ripened into being her own. This process engaged Romi and her close environment with remembering her mom, from a safe distance. The creative process, film in this case, mediated and facilitated their agony (Lev, 2020a), enabling observation of their pain.

The book Writing the Self in Bereavement: A Story of Love, Spousal Loss, and Resilience is yet another demonstration of writing as a therapeutic means for building resilience (Lengelle, 2020). The book presents the author’s grief for her lost spouse by engaging in research, poetry, and mindfulness while making transitions between mundane activities, from her life before his death to the acknowledgement of the significant resources in her life without him as her support circle of friends and close family members.

Swiss news coverage revealed a panel of expressive therapists and creators at the World Health Organization COVID-19 art festival and Create 2030. In the panel, emphasized the importance of art therapies in providing routes for connection, expression, respite, narrative organization, and perspectives among adults, adolescents, and health workers on the front and second lines during the global pandemic. The discussion at the festival presented the growing relevance of art in its ability to express feelings of instability, uncertainty, confusion, and anxiety, thus reducing the cumulative damage that has been done to the public following the pandemic. The festival featured hip-hop singing and dancing by teenagers, an online exhibition of visual artworks, storytellers in different languages, and theater performances.

Sajnani (2020) shared on social media that, from the beginning of the plague, it was the artists who allowed us to maintain a sense of humanity and our sanity in some cases, even during lockdowns and quarantine. What started as a 700-member private Facebook group has become an online community of artists who support one another in works and ideas (Bailey, 2020; Davis, 2021; Harris & Holman Jones, 2021).

A few years earlier, Gennaro Garcia (2015) proposed a model for coping and developing resilience through an art-based pedagogical study involving immigrant students in Claremont, CA, USA. Garcia invited participants to paint on school walls and express their feelings of oppression and rejection. The colorful images on display allowed them to recognize the pain and difficulty that seemed to be a collective property of the community. Pain researchers also believe that an active willingness to be present in pain, to see it as an integral part of their lives along with the thoughts and feelings that accompany it, leads to its acceptance and relief of its symptoms (Lynch, Sloane, Sinclair, & Bassett, 2013).

Communal participation through creation invites participants to express complex emotions and demonstrate various perspectives. This was seen in a two-day art-based symposium that focused on processing trauma cases and suicidal tendencies, gathering participants from diverse cultural communities through drama, music, creativity, and writing (Silverman, Smith, & Burns, 2013). The findings of the study demonstrated how these creative tools in group supportive settings provided the safe distance and confidence participants needed to observe their pain.

Group Support and Resilience

Romi’s film, To the Sky and Back, engaged a community in the creative process (n=22). She wrote the screenplay in the third person, narrating her story as a teenage girl who lost her mother to cancer. Along with Romi were four leading actors, 12 bystanders, two photographers, a director, a producer, and a soundman—a community assembled from Romi’s close friends and family members. Aside from three leading professional actors who auditioned for their parts, I, her mom’s close friend, was invited to play a lead role.

My character was an angel, guiding the girl on her journey to find her mom’s voice within. The metaphoric responsibility that was trusted in me by Michal, before she passed away, was now put in script by her daughter, Romi. The project took approximately one year to complete, through which I was given the opportunity to spend valuable time with Romi and the creative team—to provide my house, bedroom, and bath for one of the leading scenes, to read and edit parts of the script, to rehearse, to act, and then watch the premiere sitting next to her father. All throughout the process, I felt supportive and supported.

It is widely recognized that teams supporting one another, who are flexible, and who promote creative thinking are also recognized as furthering resilience among group members (Ben-Dori Gilboa, 2013). This belief was also strengthened in a recent study conducted in Lithuania (Vaičekauskaitė, Grubliauskienė, & Babarskienė, 2021) that examined the experiences of public health experts working at COVID-19 testing stations and call centers during the March–June 2020 pandemic. The research finding captured that creative thinking fosters resilience. The results of the study highlight virtues such as humor, imagination, insight, and meaning, which are also characteristics within artmaking that can lead to social resilience.

Even in broad social aspects, art enables creators to express difficult emotions that are often repressed and provokes action to bond communities. Such is the work of the photographer Jean Rene, known as JR, who paints black-and-white close-up portraits and, with the help of local volunteers, applies them on public buildings and environments around the world. This partnership between the artist and community members allows them presence and a sense of ownership of their environment (Thompson, Remnant, & Azoulay, 2015).

As an art therapist, I testify to the significant contribution that art and resilience have toward one another. Hazut (2005), who explored the resilience of an art therapy group, suggested that when the group becomes a supportive and inclusive container for its members, they feel an alliance, respectfully. Her findings resonate with other group therapists who believe that by dealing with situations of distress or anxiety, which naturally arise during the construction and existence of a group, participants actively learn about their own resilience. An awareness of one’s strengths provides confidence and develops tools and abilities to deal with similar situations outside the group setting (Yalom & Leshetz, 2006; Mosek & Ben-Dori Gilboa, 2016).

In our research (Lev et al., 2021), we found the support circle to be a characteristic of resilience by recognizing difficulty in looking directly at the research topic, delving deeper into morbidity and loss amid the pandemic, imposing a concrete life-threat. We therefore invited the students’ circle of acquaintances to participate as student-co-researchers. Similar to my feelings while collaborating in Romi’s film, we were surprised by feeling both supportive of the research participants and supported by them. During the artistic processing of the research material, I wrote a poem:

Resilience.

Side by side

Light and dark

Groping

Amputated limbs

Folded in melancholy

The transparent reveals secrets of the opaque

They move around but the circle is truncated

They curve, twirl, lean

The thick with the thin

The straight and crooked

They are close and distinct

Growing from each other

and from this,

ascent

The research findings also identified the formation of structures within the research group, in the research’s division into stages, and within the structure of the group meeting. A systematic structure was maintained in dividing the research labor among the three researchers throughout the various stages. The triangle, as the most stable of all engineering structures, was used for processing the research information in three triangular encounters, as well as the circular working method that was created. The findings highlighted an esthetic observation of components in the group meeting, which revealed the circle of student-chairs (Figure 2). One of their stories, highlighted the student-co-researcher Keren, who asked to maintain an empty chair for her lost friend, Shulamit, similar to what she had done during the entire second school year, after her death.

FIGURE 2 | The circle of research participants during the group discussion.

In Hildebrandt’s (2021) article about creativity and resilience in art students during COVID-19, she wrote about her surprise in discovering growth in innovation, problem solving, introspection, and empathy within her students during online studio-art classes. One of the first characteristics of these changes resulted from the student’s base mode of showing up to class, motivated both mentally, physically, and spiritually while being dedicated to their artmaking processes. Similarly, I could observe Romi’s dedication to her creative project, which was different from her normal conduct in school before it. Hildebrandt (2021) discussed a communal vulnerability that was caused by the pandemic, which affected her students’ artworks in their choice of materials, and deep involvement. Using personal stories for performance art and artistic projects was suggested by Esser-Hall, Rankin, and Ndita (2004) as well as others who found autobiographic involvement demonstrates constructivism, that is, learning through personal experience (Hildebrandt, 2021; Van Katwyk, & Seko, 2019).

In our art-based research project, we wrote about our partnership in the process (Lev et al., 2021) where there was emphasis on and by each researcher’s personal connection to the subject. During the reflective analysis, I journaled while watching the video files:

Student Shira’s words take me back to that night with Michal at the hospice. We moved from the couch in the great room, to her bed, and back. I felt it was her last night and wanted to be with her until the last second.

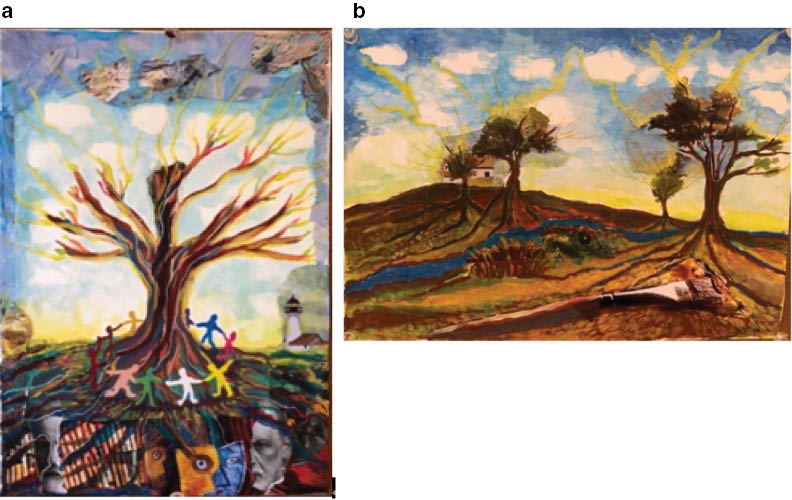

The study provided a holding framework for the grief and pain I experienced. The reflective artworks of researcher Gili demonstrated resilience as well. The solid central tree she painted in her first artwork (Figure 3a) was no longer alone in her second artwork (Figure 3b). Now, the tree was given an environment of three additional trees planted in the ground next to it. Gili said the tree was an expression of resilience in its ability to nourish itself from the air, the light, the earth. Her works emphasize the infinite powers of creation, and our ability to rely upon the cycle of nature in dealing with pain, illness, and loss.

FIGURE 3 | (a) Gili’s response art. Collage work on paper (35/50 cm). (b) Gili’s response art. Collage work on paper (50/35 cm).

In the 21st century, we have come to recognize art’s role in the identification and expression of distress and in allowing space for coping through it, which lead to transformation and improved well-being. Humanitarian organizations around the world such as the World Bank understand the importance in raising awareness to the impact of disasters and social change in a developing world (Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery, 2020).

Faith as an Aspect of Resilience

In times of global uncertainty and shattering of absolute truths, humans seek their forces in faith (Osho, 2010). This was relevant for the collective world grief caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and continues to be significant for the current bloodshed in Eastern Europe. In the ancient Torah, the use of magical symbols was commonplace, yet these have retained their resilience to present times through the creative language (Knill, 1999). Arnheim (2004, p. 327) demonstrated this conception when he wrote: “The most gigantic formations on earth are made into apparitions.”

The name of Romi’s film To the Sky and Back carries in itself a belief in higher power. The last scene shows the teenage girl, standing in her backyard, hesitantly glancing at the skies. She is finally ready to acknowledge her mom’s presence as a force in nature, echoed within as an understanding revealed to the viewer by the girl’s ability to direct her gaze toward the sky. Along her side, stands her father, who silently joins this belief and raises his head up to stare at the sky. The girl’s search for her mother’s spirit displays a symbolic belief in resilience. This last scene illustrates Romi’s separation-individuation process through peace-making and acceptance. It also demonstrates the perception of resilience according to the American Psychological Association (2009) in which the development of mental resilience interweaves identifying thoughts and beliefs that both limit and contribute to the personal advancement of those who need it.

Art can be treated as the extant common belief in the world. It is no surprise to find an overlap between the word art (אמנות) and beliefs (אמו נות) in Hebrew writing. As our research (Lev et al., 2021) demonstrated, an art-based research paradigm is based on the belief in the forces of science, nature, and man as inherent components and motivation for research action (McNiff, 2013). In fact, our choices to engage in artmaking reinforce our faith in the creative process as allowing ambiguity in a symbolic space by “trusting the process” (McNiff, 1998), which forms another representation of human resilience.

As mentioned earlier, a natural element within artmaking is ambiguity, which according to D’Mello, Lehman, Pekrun, and Graesser (2014), is essential for building resilience for those willing to risk failure. The challenges that exist in the creative process promote deep inquiry and re-deliberation (Fransen, Peralta, Vanelli, Edelenbos, & Olvera, 2022). Leader (2008, p. 207) added that the man-made materiality of an artwork can encourage creators to recognize their inherent power, especially when looking at the finitude of life: "Something new is created from loss in these situations and it ultimately inspires us all.” Wright (2014) strengthened this perception and suggested that the importance of an object, ready or created, is subject to the creator’s ability to adopt an esthetic, imaginative, thoughtful position in a certain way, setting aside practical concrete action.

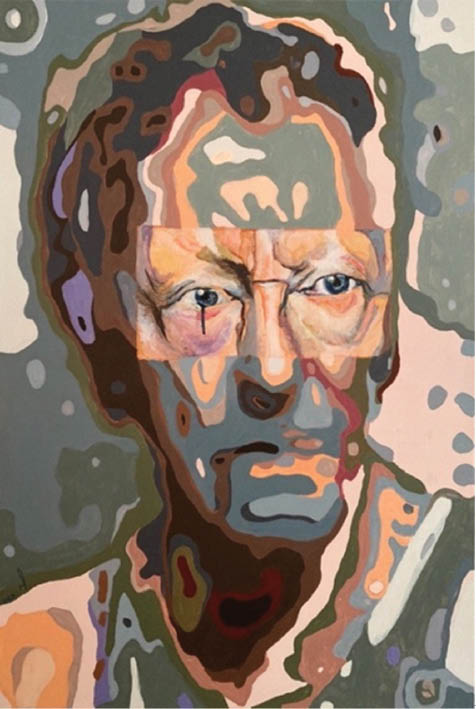

In our research, we recognized that the component of faith deals with a power and knowledge greater than man, linked with a belief in the self (Lev et al., 2021). In search of an answer to the elements of resilience, my creative response Resilience: Video Art (https://youtu.be/s0_KFYFBZI4) (Lev, 2020c) entails the developmental stages of an artwork presenting an archetypal old warrior (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4 | Michal’s response art: The Old Warrior. Acrylic and watercolors on canvas (60/80 cm).

Through dissemination and change in the work, it suggests that resilience is diffusive, relative, and can therefore be developed. The video begins with a central rectangle frame with two eyes painted in watercolors; then, the creation of a background assimilating a topographic map in acrylics evolves into the image of a man. The background enmeshes the image, symbolizing their inherit synthesis.

In his video series The Warrior Archetype (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_MsmdDEcGKw), Pressfield (2020) relates the virtues of the heroic warrior to ordinary people, dealing with COVID in contemporary times. Similarly, the nine of us surrounding, caring for, and honoring Michal on her last journey resonates with Pressfield’s perception. During her last hours in the hospice, Michal seemed to exist within the liminal space between heaven and earth. In a silent, slow voice, she extracted words of wisdom recollected from a higher dimension, as if she knew she would not live to see another day and had already summoned spirits of change and angels to escort her.

We can therefore conclude that our ability to imagine folds a belief in a dimension greater than matter and to adopt an interpolated mindset between realities.

Epilogue of Eulogy

Leonard Cohen’s last album You Want it Darker (2016) was published 19 days prior to his death. In it, the song Hineni [I am, for you, my lord] seems like Cohen’s own obituary, citing lines from the Hebrew prayer Kaddish, words that are usually read for the dead:

If you are the dealer, I’m out of the game

If you are the healer, it means I’m broken and lame

If thine is the glory then mine must be the shame

You want it darker

We kill the flame

Magnified, sanctified, be thy holy name

Vilified, crucified, in the human frame

A million candles burning for the help that never came

You want it darker

Hineni, hineni

I’m ready, my lord

Hineni, hineni

Hineni, hineni

I’m ready, my lord

Hineni

Hineni, hineni

Hineni

Cohen’s poetry displays the three salient operative elements of resilience that were found in the art-based research project about sickness and death (Lev et al., 2021) and within Romi’s film To the Sky and Back (Toledano, 2021): observing pain, faith, and support circle.

These elements feature the role of art in connecting to an intangible existence, through concrete materials. For a group sharing a destiny, the maintenance of hope transpires for the dying and the living circle of support, simultaneously. Consequently, inviting an extension of the bereavement from the creator to those witnessing and observing it. Romi’s search for Michal’s voice continues to beat within, reminiscent with our circle of support that vibrates and echoes her living spirit.

About the Author

Dr. Michal Lev is a board-certified art therapist, supervisor, and a certified family psychotherapist. Her clinical practice included inpatient and outpatient treatments for adults with mental health issues. In her established private practice for couples and families, Michal incorporates expressive therapies to deal with intimacy issues and promote wellbeing. Michal is a faculty lecturer at the Graduate Art Therapy Program at Ono Academic College–ASA in Israel, advising students in their seminar thesis and promoting art-based pedagogy and research. Her published research and presentations focus on intimacy, art-based research, and creative process-oriented pedagogy. Dr. Lev is the head of the approval committee for YAHAT—the expressive therapies organization in Israel since 2016, supporting public legislation for expressive therapies. As a social activist, artist, and entrepreneur, she maintains artmaking for innovation, inquiry, and knowledge within business environments.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; michlev@gmail.com; Tel.: +972(54)6616280; www.levmichal.com.

References

Aburn, G., Gott, M., & Hoare, K. (2016). What is resilience? An integrative review of the empirical literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(5), 980–1000.

Arnheim, R. (2004). Art and visual perception: A psychology of the creative eye (Rev. and expanded ed.). University of California Press.

Bailey, C. (2020, November 20). The pilgrimage & the pandemic [Online discussion]. Retrieved on April 6, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch.

Ben-Dori Gilboa, R. (2013). Employing art in group dynamics: As means to develop resiliency in professionals working with youth at risk. Journal of Society and Education, 24, 34–37.

Chmitorz, A., Kunzler, A., Helmreich, I., Tüscher, O., Kalisch, R., Kubiak, T., Wessa, M., & Lieb, K. (2018). Intervention studies to foster resilience—A systematic review and proposal for a resilience framework in future intervention studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 59, 78–100.

Cohen, L. (2016). You want it darker. Retrieved on Oct. 23, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v0nmHymgM7Y.

D’Mello, S., Lehman, B., Pekrun, R., & Graesser, A. (2014). Confusion can be beneficial for learning. Learning and Instruction, 29, 153–170.

Davis, S. (2021). Perezhivanie, art, and creative traversal: A method of marking and moving through COVID and grief. Qualitative Inquiry, 27, 767–770.

Esser-Hall, G., Rankin, J., & Ndita, D. J. (2004). The narrative approach in art education: A case study. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 23(2), 136–147.

Fransen, J., Peralta, D. O., Vanelli, F., Edelenbos, J., & Olvera, B. C. (2022). The emergence of urban community resilience initiatives during the COVID-19 pandemic: An international exploratory study. European Journal of Development Research, 34, 432–434.

Garcia, L. G. (2015). Empowering students through creative resistance: Art-based critical pedagogy in the immigrant experience. Diálogo, 18(2), 139–149.

Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery. (2020). The art of resilience. Retrieved Dec. 24, 2021, from https://www.artofresilience.art/about/.

Harris, A., & Holman Jones, S. (2021). Massive and microscopic: Autoethnographic affects in the time of COVID. Qualitative Inquiry, 27, 861–869.

Hazut, T. (2005). From dark black to bright pink. In D. Kalmanowitz & B. Lloyd (Eds.), Art therapy and political violence: with art, without illusion (p. 91). Routledge.

Hildebrandt, M. (2021). Creativity and resilience in art students during COVID-19. Art Education, 74(1), 17–18.

Knill, P. J. (1999). Soul nourishment, or the intermodal language of imagination. In S. K. Levine & E. G. Levine (Eds.), Foundations of expressive arts therapy: Theoretical and clinical perspectives (pp. 37–52). Jessica Kingsley.

Lahad, M. (2017). From victim to victor: The development of the BASIC PH model of coping and resiliency. Traumatology, 23(1), 27–34.

Leader, D. (2008). The new black: Mourning, melancholia and depression. Penguin UK.

Lengelle, R. (2020). Writing the self in bereavement: A story of love, spousal loss, and resilience. Routledge.

Lev, M. (2019). Painting intimacy: Art-based research of intimacy. Dissertation, Lesley University, Cambridge, MA. Retrieved on March 12, 2022, from https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_dissertations/60/.

Lev, M. (2020a). Art as a mediator for intimacy: Reflections of an art-based research study. Journal of Applied Arts and Health, 11(3), 299–313.

Lev, M. (2020b). In sickness and death—Final edited video [Video-art]. YouTube. Retrieved on Feb. 4, 2021, from https://youtu.be/iRp-kx--Q5E.

Lev, M. (2020c). Resilience: Video art [Video-art]. YouTube. Retrieved on Feb. 23, 2022, from https://youtu.be/s0_KFYFBZI4.

Lev, M., Kats, A., & Navoth, G. (2021). In sickness and death: An art-based pedagogical research. In T. Yaguri & D. Merari (Eds.), Art in action: Teaching, training, and research in art therapy (pp. 78–98). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Li, C., & Psarra, S. (2022). Building pandemic resilience in design: space and movement in art museums during Covid-19. SocArxiv.

Lynch, M., Sloane, G., Sinclair, C., & Bassett, R. (2013). Resilience and art in chronic pain. Arts & Health, 5(1), 51–67.

McNiff, S. (1998). Trust the process: An artist’s guide to letting go. Shambhala.

McNiff, S. (2013). 9th Annual Congress of Qualitative Inquiry in ABR.

Mosek, A. A., & Ben-Dori Gilboa, R. (2016). Integrating art in psychodynamic-narrative group work to promote the resilience of caring professionals. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 51, 1–9.

Osho. (2010). Destiny, freedom, and the soul: what is the meaning of life?. St. Martin’s Griffin; Godalming: Melia [distributor].

Pressfield, S. (2020, August 17). The warrior archetype series [Video].

Sajnani, N. (2020, June 23, 2020). WHO Panel Discussion taster: The role of arts & arts therapies in the context of the pandemic 1m30. Retrieved on Dec. 10, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sPRMBxqw6Nc.

Silverman, Y., Smith, F., & Burns, M. (2013). Coming together in pain and joy: A multicultural and arts-based suicide awareness project. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 40(2), 216-223.

Thompson, N., Remnant, J., & Azoulay, M. (2015). JR: Can art change the world? Phaidon Press.

Toledano, R. (2021). To the sky and back. Alon High-School.

Tzameret, D., & Barkani, H. (1974). And wheat grows again. Kibbutz Beit Hashita. https://www.beithashita.org.il.

Vaičekauskaitė, R., Grubliauskienė, J., & Babarskienė, J. (2021, March 8–9). Resilience to pandemic by use of creative thinking: Experience of Lithuanian public health professionals. In 15th International Technology, Education and Development Conference.

Van Katwyk, T., & Seko, Y. (2019). Resilience beyond risk: Youth re-defining resilience through collective art-making. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 36(6), 609–619.

Wright, K. (2014). Maternal form in artistic creation. Free Associations(65), 7–21.

Yalom, D. I., & Leshetz, M. (2006). The therapist—Fundamental actions. In Group therapy: Theory and practice. Kineret, Zmora-Bitan, Dvir.