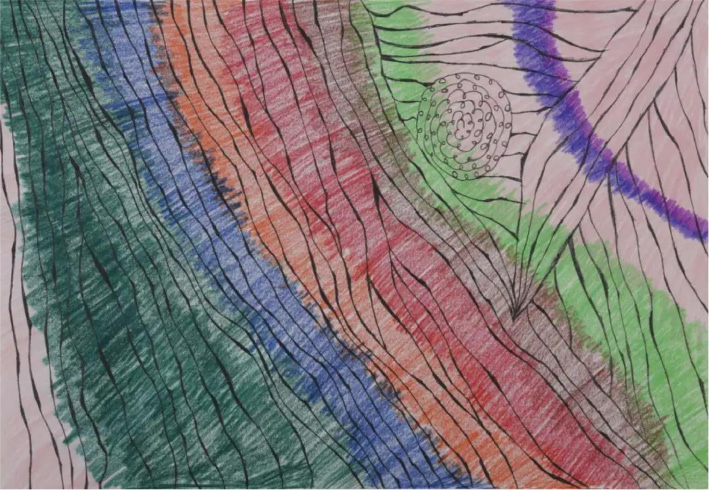

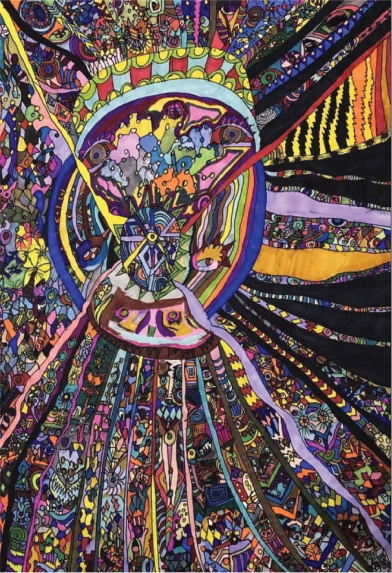

FIGURE 1 | Universe Union: Breaking Dawn (Niu, 2015).

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2021) 7(2):128–137 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2021/7/11 |

A Dialogue with Guo Haiping: The Concept of Universe in the Nanjing Outsider Art

对话郭海平:南京原生艺术中“宇宙”概念

1Nanjing Outsider Art Studio

2Creative Arts in Education and Therapy

3The Ethel Walker School

Abstract

Native artists in Nanjing Outsider Art Studio are individuals who have been medically diagnosed with different types of mental illness who have been socially isolated for a long time and without a high school diploma. Half of them spent only a few years in special schools for various mental and intellectual disabilities. Why are the native artists with less education who experience mental illness so interested in the study of the universe? In an in-depth interview with Guo Haiping and Aimee T. Liu, Guo shared his explanations of this phenomenon in the sphere of transpersonal psychology.

Keywords: China outsider art, Universe, Haiping Guo, transpersonal psychology

摘要

南京原生艺术工作室的艺术家都是被医学诊断为患有不同类型精神疾病的人,他们长期脱离社会,而且都没有读完高中,甚至有一半只是在为精神和智力障碍者服务的特殊学校上过几年学。对于这些文化水平普遍不高,而且还患有不同类型精神疾病的人而言,他们为什么会对宇宙产生如此的兴趣呢?在中,郭老师在超个人心理学中发现了对于这一现象的更多阐释。

关键词: 中国原生艺术,宇宙,郭海平,超个人心理学

Aimee: You have devoted yourself to the work of China outsider art nearly 20 years, how do you understand the concept of the universe in your work?

Haiping: When it comes to the universe, this should be more concern for the scientists than us, the nonscientists who have long been educated in materialism; after all, the universe is too far away from us. However, constantly seeing the “universe” drawn by native artistsin the Nanjing Outsider Art Studio, I started to be interested in the universe between Eastern and Western cultures.

In Chinese tradition, the firmament is the god of everything. While the human being is a small universe, the firmament is the big universe enclosing the small one. Chuang Tzu once said, “Heaven and Earth coexist with me, and everything unites with me” (Wang, 1983, p.38). This saying, along with Jiuyuan Lu’s statement that “The universe is my heart, so is my heart the universe” left a significant impact in China. In addition, Chinese people like to name the universe “Tao” (Ge, 2018). What is “Tao”? “Before the Heaven and Earth existed, there was something nebulous: Silent, isolated, standing alone, changing not, eternally revolving without fail, worthy to be the Mother of All Things. I do not know its name, and address it as Tao. If forced to give it a name, I shall call it “Great,”” explained by Lao Tzu (Ren, 1985, pp. 113–114).

The native artists in our art studio are individuals who have all been medically diagnosed with different types of mental illness. They have been socially isolated for a long time, dropped out of high school, and half of them only had education in schools specialized for people with mental and intellectual disabilities. For these mentally disabled people receiving low education, their interests in the universe can be attributed to their less access to current culture because of their illness, preserving their love for nature more. Thanks to such attachment, the “small universe” within their body bonds closely with the big universe outside. Lao Tzu said, “The thing that is called Tao is elusive, evasive. Evasive, elusive, Yet latent in it are forms. Elusive, evasive, yet latent in it are objects” (Ren, 1985, p.104). Perchance this is what the native artists felt when they were depicting the universe of their own.

Compared to Oriental culture, traditional Western people believe that material and spirit, sense and sensibility, and subjectivity and objectivity are disparate. With the development of such a mindset, the relationship between humans and nature becomes more tense and divided, ultimately leading to a sense of helplessness and solitude. Entering the postmodern society, Western people realize that they must get rid of the dualism mindset. Freud and Jung were the first Western psychologists to explore the connection between individuals and the world. For instance, according to Jung, personality is a spacious and secretive system; the inner world of humans is like the universe, so the most honorable exploration of one’s life is one of the inner worlds. Once human beings dig deep into one’s soul, achieving the unity of nature and humanity psychologically, they reach the immortality of the universe.

Aimee: I’m so curious about the explanations of this phenomenon that some people with mental illness perceive the universe differently than those without mental illness. Could you say more?

Haiping: Some people with mental illness perceive the universe differently than those without mental illness. This could be because of their unique talents or because of their illness and psychological barriers, which paradoxically free them from the confinement of intellectual concepts and logical thinking, so that they remain, or regain the wisdom of our human ancestors. This wisdom enables those with mental illness to be unified with all things in nature. The first psychologist to systematically study this wisdom is Carl Jung. In one of his most convincing studies, he reveals the results of the human collective subconscious and collective subconscious archetype where he discovered that the wisdom of human ancestors is still preserved deep in the hearts of modern people. This discovery stemmed precisely from his psychotherapy practice.

Jung was referred to as “the ancestor of transpersonal psychology” by his successor, Grof, who was one of the founders of transpersonal psychology. As a famous psychiatrist, Grof impressed me by the results of his research on the “full return state” of human consciousness. “In a state of total regression, our sensory perception changes dramatically,” Grof (2000, p.3) wrote in the book of Psychology of the Future: Lessons from Modern Consciousness Research. When we close our eyes, our visual field is filled with images of our personal history, individual, and collective subconscious. We will have many visual experiences about plants, animals, and nature or all aspects of the universe that can take us into the field of archetypal life (the existence of archetypes) and mythological experiences. Grof refers to this human experience of the universe as “the prototype experience of the universe” (p.55) and “the experience of the universe consciousness” (p.55). For these archetypal experiences, Jung explains, “after the mind loses its balance, it reveals spontaneously in the process of spiritual re-integration” (Deng & Luo, 2003).

Aimee: Well, could you give us a sense of what you see the native artists are doing and presenting, i.e., what they say and paint?

Haiping: At this point, let’s take a look at the universe-related native art created by our studio’s native artists. The first time I saw them painting the universe was in 2015. On June 2, 2015, Niu created a picture of Universe Union (see Figure 1) at around 4 p.m., it took her three hours to finished the work with intense emotional ups and downs. She had just painted for over an hour, and the weather outside suddenly became gloomy with strong winds, followed by lightning and thundery pouring. I noticed Niu was intensely focused when she drew the picture, and I could see from her occasional looking up at us that she seemed to be dealing with great urgency and that the rapid and constant painting along the thunder outside the window made the atmosphere particularly tense. The painting was finally finished at 7 p.m., when the weather outside began to calm down and the air became extraordinarily fresh. After Niu drew the picture, she immediately wrote Universe Union on the back of the painting, and then the subtitle, Breaking Dawn. In the days that followed, she painted three more works, Universe Union: Slag, Universe Union: Rain Echo (see Figure 2), and Universe Union: The King’s Hometown.

FIGURE 1 | Universe Union: Breaking Dawn (Niu, 2015).

FIGURE 2 | Universe Union: Rain Echo (Niu, 2015).

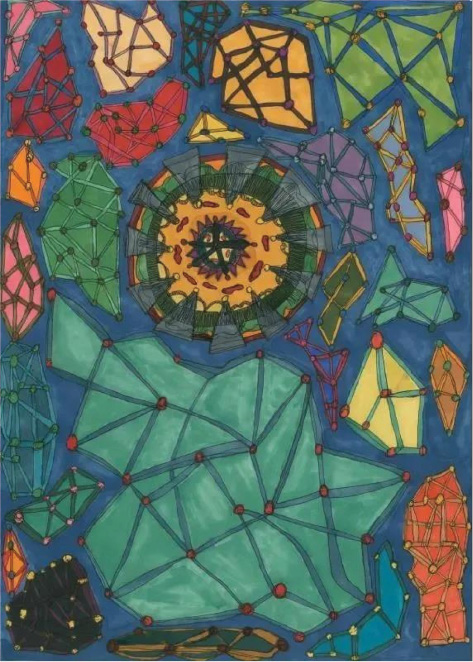

Back in April 2017, Xu Jian painted the Cosmic Law Front (see Figure 3). When I asked him about his process, he replied, “last night I had a dream with many stars.” Two months later, he was home resting for a month because of surgery. After his return to the studio, he drew Cosmic Planet (see Figure 4). I asked him about his process again, to which he smiled and replied, “I don’t know.” Not knowing why they painted these works involving the universe is the common answer. It seems to me that what they say “don’t know” refers to the consciousness of thought; their hearts are very clear why they draw these paintings, and this “heart” refers not to what we usually call the sense of thinking, but to the subconsciousness and the natural willpower of life.

FIGURE 3 | Cosmic Law Front (J. Xu, 2017).

FIGURE 4 | Cosmic Planet (J. Xu, 2017).

Xu Jian has been medically diagnosed as having an intellectual disability, different from Niu Niu’s undifferentiated schizophrenia. Niu Niu’s universe painting is more abstract, and Xu Jian’s appears more concrete. Xu Jian told me that the circle in his Cosmic Law was a compass, which means that the movement of the stars, has a clear direction Niu Niu’s Cosmic Union—Dawn is more like a rotating Chinese tai chi map and Jung’s mandala. Jung believed that the spiritual structure of man is aligned with the structure of the universe and that everything that happens in the macro world will also happen in the human mental world, “mandala represents it (monad), and corresponds to the microcosmic nature of the mind” (Shen & Gao, 1998, pp. 251–252).

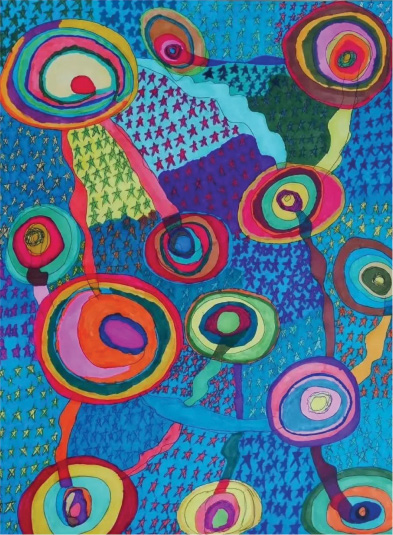

Qiao Yulong is a cerebral palsy patient. His thinking is entirely on the right side of brain. In November 2017, Qiao Yulong painted Aliens Bring Chicks, Electric Toys to the Universe (see Figure 5). In May 2019, he drew another, Cosmic Bugs, and on October 20, 2020, The Universe Today (see Figure 6). My initial impression was the first two paintings were influenced by others, until he recently painted the Universe Today, which I felt was not accidental. To further confirm that he completed it independently, I asked him to explain his work. He replied, “the skull-like earth in the middle of the picture is a wise brain, around the emission-shaped color lines are light, emission color lines between the various shapes are all kinds of living things.” I asked him what the wide black stripes on the right expressed. “That’s the back of the universe,” he said. He also told me that he drew the universe because it seemed to him more mysterious and attractive than reality.

FIGURE 5 | Aliens Bring Chicks, Electric Toys to the Universe (Qiao, 2017).

FIGURE 6 | The Universe Today (Qiao, 2020).

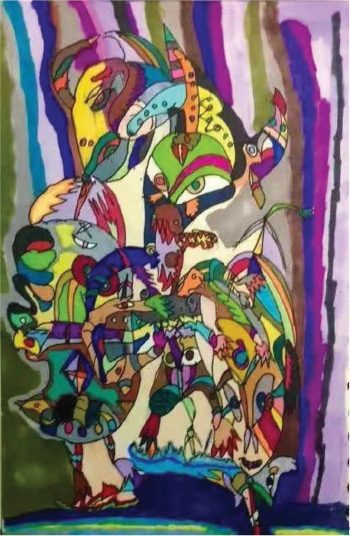

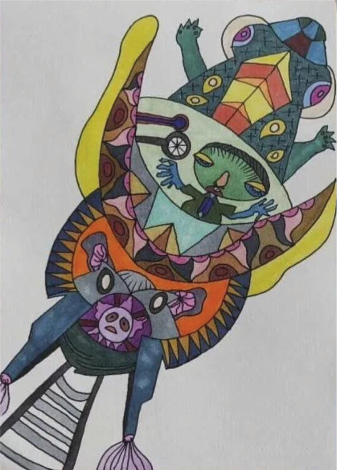

Tian Peng is also a schizophrenic recoveree. In 2019, he painted Spaceship Landing on Earth (see Figure 7) and Cosmic Black Hole (see Figure 8). Compared with Niu Niu, Xu Jian, and Qiao Yulong, Tian Peng also has his own characteristics and is particularly interested in drawing a variety of animals. His animals are different from animals in nature and generally have the attributes of human and divine. The spacecraft in Spaceship Landing on Earth looks like a frog with a pair of wings, and for Tian Peng, it is through these magical animals that he united heaven, earth, man, and God. In his painting The Black Hole of the Universe, every planet in the universe is also the face of different magical animals; in his mind, the universe is made up of these omnipotent animals.

FIGURE 7 | Spaceship Landing on Earth (Peng, 2019).

FIGURE 8 | The Black Hole of the Universe (Peng, 2019).

Aimee: All in all, I find that the focus on the universe is so fascinating and important to the artists. The power of universe was a strong influence on their painting. Could you say more about such magical power from nature?

Haiping: The reason why these native artists, with different types of mental illness, seek refuge in referring to the universe in their art could be due to our culture not supporting their spiritual development, often becoming a barrier to their recovery. When they are overcome by universal support, they have to return to their innermost wisdom, where they receive this magical power from nature. Only this kind of strength can give them great mental comfort. As Grof (2000, p. 19) puts it, “The study of the full regression state shows us a surprising change that activates the innermost wisdom of the treated person, which leads him into the process of transformation and therapy.” Another transpersonal psychologist, Brant Cortright (1997, p. 11), wrote in his book Psychotherapy and Spirit: Theory and Practice in Transpersonal Psychology, “Psychosis is not just a pathological drowning of the ‘self’, but also a psychic opening that can lead to the power of the wider universe and increase the possibility of spiritual and psychological healing.”

Transpersonal psychology is also called “surreal psychology,” and this new psychological theory is called the “fourth force,” after behaviorism, psychoanalytic analysis, and humanism psychology. It is called the fourth force because other psychological theories, no matter how they interpret human psychological activity, always exclude the true spiritual experience of human beings, intentionally or unintentionally. In this exclusion, human psychological activity can only be a mechanical material activity, which is obviously not in line with real life that each of us experience. The value of transpersonal psychology lies precisely in its full affirmation of spirituality in human life, in the view of transpersonal psychology, “the essence of human beings is spirituality” (Cortright, 1997, p. 13). This understanding not only transcends the materialized thinking in traditional psychology, but also creates the conditions for spirituality to return to human life, and at the same time, it alters prejudices against mental illness. This spiritual return is precisely the reason why humans have re-established a far-reaching and well-rounded connection with the world.

About the Authors

Guo Haiping, 郭海平, a contemporary artist, the pioneer of Chinese outsider art, is the founder of the Nanjing Outsider Art Studio and the chief editor of Outsider Art Series. He devoted himself to the discovery and research of outsider art of people with mental disturbance for changing the environment of Chinese culture. He established the first art institute for patients with mental illness in 2010 and established two outsider art studios in the community of Jianye District and the community of Gulou District in Nanjing. His books include Out of the Maze of Mind, Sunbathe: Art Projects of 20 Years, I Am Sick, Therefore I Am, and Notes of Outsider Art in China.

Aimee T. Liu, 刘婷, was previously a lecturer at the Psychological Counseling Center at Beijing Contemporary Music Academy, China. She is currently the secretary for the Chinese Group of Arts Therapy, the Chinese Psychological Society, and is also an acquisitions editor of Creative Arts in Education and Therapy (CAET).

Katherine Tang, 唐恺文, is a student at the Ethel Walker School in the United States. She has great interest in psychology and music and aims to pursue these two fields further.

References

Cortright, B. (1997). Psychotherapy and spirit: Theory and practice in transpersonal psychology. Shanghai: Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press.

Deng, X. & Luo, P. (2003). C.G Jung’s psychological theory and Tibetan culture. Journal of Tibet University, 1, 53–56+74.

Ge, Z. (2018). An intellectual history of China, volume two. Shanghai: Fudan University Press.

Grof, S. (2000). Psychology of the future: Lessons from modern consciousness research. Yunnan: Yunnan People’s Publishing House.

Ren, J. (Trans.). (1985). New translation of Lao Tzu. Shanghai: Shanghai Classics Publishing House.

Shen, H. & Gao, L. (1998). C.G Jung and Chinese culture. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 30, 219–223.

Wang, S. (1983). Translation and annotation of Chuang Tzu. Shandong Sheng: Shandong Education Press.