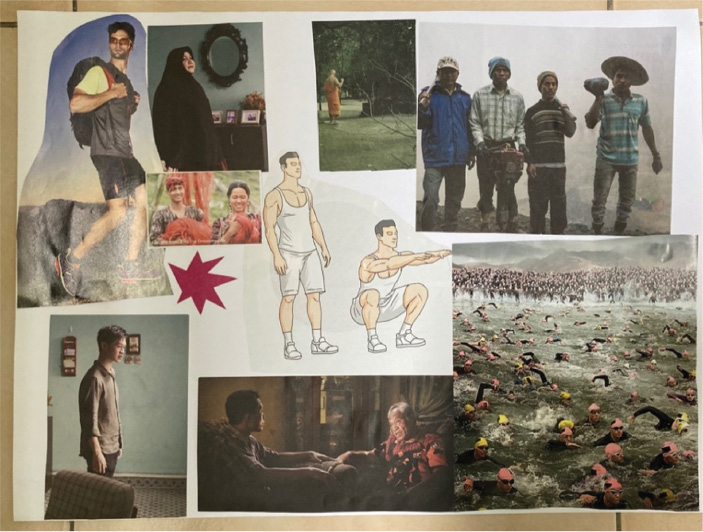

FIGURE 1 | Joint painting procedure.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2021) 7(2):200–215 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2021/7/21 |

Arts-Based Program for Home-Based Care Dyads in Singapore

新加坡居家护理二分体艺术干预计划

Lesley University, USA

Abstract

This article describes an arts-based intervention program for seven care dyads of elderly persons and their caregivers who are foreign domestic workers (FDWs) in Singapore. The intervention aimed to introduce interdisciplinary tools of artmaking and mindfulness that could be used to improve the communication and relationship between the care dyad and to support the stress reduction and self-care of caregivers. Following a client-based approach, eight sessions were conducted, once weekly, over a 2-month period in hybrid structure, at the home of the care dyad and through the use of Google Meet. Qualitative data were collected in personal interviews, questionnaires, and visual data, and they were connected with art therapists’ fieldnotes and reflection journals. At the end of the program, an online feedback session was offered to the elderly participants’ family members, and their feedback was collected using a questionnaire. The data analysis confirms the impact of the artmaking intervention on the communication and relationship of the dyad. Participants reported that artmaking combined with mindfulness tools contributed to their understanding of their care-recipient (CR)/caregiver, improved their daily care activities, and helped caregivers explore new ways of self-care and stress relief. The hybrid model of implementation was effective and encouraged caregivers to explore and practice the tools learned independently between sessions. The results of this pilot program inform the development of intervention programs for care dyads as well as training programs for both caregivers, art therapists, and other care professionals. The intervention for care dyads highlights the importance of dyadic care as part of a holistic approach to caregiving. The inclusion of FDWs in the program suggests that both CRs and caregivers are one unit in which their well-being is interdependent. Further research may explore specific artmaking activities for other dyads of caregivers and CRs with differing care needs and backgrounds. Potential training activities and models could support the use of this intervention by therapists and other professionals.

Keywords: art-based, mindfulness, care dyad, self-care, homecare, elderly, domestic workers, hybrid intervention, Singapore

摘要

本文介绍了一项以艺术为基础的干预计划, 该计划已应用于新加坡的七对年长者以及担 任其照顾者的外籍家庭佣工。该干预计划旨在引入艺术制作和正念的跨学科工具, 改善 护理二分体 (即年长者与其照顾者形成的一个单位) 之间的沟通和关系, 并支持照顾 者减压和自我照顾。该计划遵循以个案为中心的方法, 历时两个月时间, 以每周一次, 一共八次, 混合式结构的方式, 在护理二分体的家中通过使用 Google Meet 视频会 议进行干预。本研究通过个人访谈、问卷调查和视觉数据收集定性数据, 并将这些数 据与艺术治疗师的实地记录和反思日志结合起来。在干预计划结束时, 计划实施者为 年长参与者的家人提供了一次在线双向反馈会议, 并通过问卷收集了家人的反馈。数据 分析证实了艺术制作干预对护理二分体的沟通和关系的正面影响。参与者报告说, 艺术 制作与正念的工具相结合, 有助于他们了解对方 (照顾者/被照顾者), 改善他们的 日常护理活动, 并帮助照顾者探索自我照顾和缓解压力的新方法。实施的混合式模型 是有效的, 并鼓励照顾者在视频会议干预以外的时间独立探索和练习所学到的工具。 该试点计划的结果为护理二分体干预计划的制定以及照顾者、艺术治疗师和其他护理专 业人员的培训计划提供了信息。针对护理二分体的干预计划强调了二分体式的护理 作为全面护理方法的一个重要组成部分。将外籍家庭佣工纳入该计划表明, 被照顾 者和照顾者是一个单位, 他们的福祉相互依存。进一步的研究可以探索针对其他具有 不同护理需求和背景的照顾者和被照顾者的特定艺术制作活动。潜在的培训活动和 模型也可以支持治疗师和其他专业人员使用这种干预。

关键词: 以艺术为基础, 正念, 护理二分体, 自我照顾, 居家护理, 年长者, 家庭佣工, 混合式干预, 新加坡

Introduction

This article presents an arts-based program (ABP) intervention that aims to reduce stress and improve the communication and relationship of care dyads composed of foreign domestic workers (FDWs) and elderly care recipients (CR) in Singapore. For this article, the term arts-based program represents the incorporation of the cross-modality and transdisciplinary practice (Colbert & Bent, 2018), using materials that support visual arts activities, games, literature, body and mindfulness activities, and creative expression. The program introduced daily activities in artmaking and mindfulness as an avenue to improve the care environment, communication and relationships between the care dyad, and the quality and sustainability of care-work.

The aging of the population is a global phenomenon, influencing the provision of long-term care for an increasing number of frail older people who are cared for at home. The interactions between caregiver and CR influence the quality of care as well as the health and quality of life in the care dyad environment. There are many factors that impact the life experiences and well-being of both caregiver and CR, including challenges faced by FDWs in the host country, the burden of care-work, and medical conditions of CR. In this context, the ABP explored the impact of artmaking activities on the care dyad communication and relationships and experiences of stress reduction and helped in training caregivers for self-care to reduce burnout due to the burden of care.

The ABP was implemented over 9 weeks from April 1 to June 7, 2021, with seven care dyads. Using a hybrid model of implementation, weekly sessions of 60 to 90 minutes were conducted at the care dyads’ homes and online (using the Google Meet platform). Following a client-based approach, various artmaking activities and mindfulness tools were implemented. Data were collected through personal interviews, questionnaires, field notes, and observations by the author, which were documented during and after each session. In addition, visual data in the form of photographs of artmaking and artworks were documented and provide rich information to support in-depth qualitative analysis.

Recognizing the connection among arts, healing, and public health (Fancourt & Finn, 2019), this program confirms that daily creative engagement can enhance communication (verbal and nonverbal), decrease anxiety, stress, and mood disturbances, and improve psychological and physical well-being and the quality of life of the care dyad. During the ABP implementation, the care dyads experienced a shared space and activities, which worked toward overcoming language and cultural barriers (Kirsty-Bennett & Arbell-Kehila, 2021) and learning about each other. The hybrid form of the program’s implementation was found to be an avenue for improving the support of the isolated and sometimes marginalized care dyads and stimulated a continuing self-learning process.

The results of this program inform the development of a replicable model of program for use in the care dyad environment and aid toward the improvement of the quality of life, communication, mindfulness, and art appreciation. This program suggests a new model of home-based care practices that could be implemented to support a wider group of beneficiaries in Singapore. The study of this program highlights gaps in current home-based care services and informs and conveys the importance and significant impact of this field to clinicians and professionals from other healthcare, welfare, and psychological disciplines. Based on this program, broader research that could look at global implications of art-based programs for long-term home-based care is recommended. Continuing train-the-trainer programs for art therapists, social workers, and other paramedical staff and service providers for families who care for persons with long-term medical care needs should be explored further.

The Context of the Program within the Literature

Increasing evidence suggests that various art-based activities enhance the cognitive functioning, well-being, and quality of life of elderly patients (Beauchet et al., 2020; Ilali et al., 2018; Savazzi et al., 2020). The current program explored the application of activities in two areas: home-based care for elderly and transnational migrants in Singapore and care relationships, well-being, and quality of care within caregiving dyads.

Home-based Care for the Elderly and Transnational Migration in Singapore

The growing aging population as well as the increase in long-term health conditions can lead toa transition from independent living to home-care solutions for this population (Ansah et al., 2014; Carroll et al., 2016). Pitfalls of family care and differences in care concepts and skill gaps require re-conceptualization of care-work qualifications and caregivers’ training (Bloom et al., 2015; Kehila, 2018; Levine et al., 2010). The literature highlights the need for patient daily support at home, which can result in caregivers’ stress and burn-out (Au et al., 2013; Friganovic et al., 2019; Mehta & Leng, 2017; Slocum-Gori et al., 2013). Caregivers need support systems that include social networks, medical assistance, education, respite and self-care practices, and supervision (Hewko et al., 2015; McBee & Bloom, 2016; Shapiro et al., 2007; Skirrow & Hatton, 2007).

In developed countries such as Singapore, the growth of the female labor force, alongside a rapidly aging population, creates a high demand for homecare-workers (Huang et al., 2012; Suen & Thang, 2018). An increase in the number of care-workers through migration to Singapore signifies the way policy-makers deal with the growing challenges in healthcare provision. The process of increased migration of female FDWs—influenced by the global care chains (Isaksen et al., 2008)—suggests the complex social and cultural influences on transnational care structures (Muyskens, 2020; Teo, 2017). In such complex circumstances, the relational aspect of caregiving may be challenged as caregivers may struggle in adapting to their job environment and to the linguistic and cultural aspects of their client’s behavior and communication. Hence, the importance and demanding role of FDWs in providing and ensuring long-term care for elders in Singapore requires a new approach to ensure quality of care and support for the well-being of the elderly as well as their caregivers.

The home is the primary care setting for long-term care of elderly persons in Singapore. The government agencies rely on the voluntary sector and on families to offer care (Chin & Phua, 2016; Mehta & Leng, 2017; Thompson et al., 2014). Caregivers perform simple and complex tasks, make decisions, solve problems, provide emotional support and comfort, and coordinate care, which includes supervising patients and monitoring new signs and symptoms, adverse events, and positive responses to treatment (Ayalon, 2009; Kehila, 2018, 2020b; Østbye et al., 2013). With advanced technology, the home-based caregivers are expected to operate medical equipment and smart technologies to monitor the telehealth networks and digital devices for their clients (Gaikwad & Warren, 2009; Piau et al., 2019; Quinn et al., 2018). Gaps in caregivers’ skills may impact the quality of home-based care as well as the caregiver’s confidence and stress (Given et al., 2008; Kehila, 2019; Woods & Kong, 2020).

While the scholarly literature on care-work emphasizes care skills, tasks, and challenges, the literature related to FDWs and their jobs focuses on gender hierarchies, which are influenced by social and cultural hierarchies and the ambiguity in job description and in work conditions. The attempt to develop a new culture of care based on smart technologies raises new challenges. Although smart eldercare technologies may be an efficient means of maximising the reach of caregivers, in doing so they also may increase the physical, social, and emotional distance between the providers and recipients of care (Woods & Kong, 2020). This ABP, which was implemented in a hybrid structure, suggests that combination of face-to-face with distanced meetings was successful.

Care Relationships, Well-being, and Quality of Care

The quality and benefits of care depend on both the caregiver and CR. Their relationship has been linked to the caregiver’s sense of role captivity and burden (Campbell et al., 2008; Quinn et al., 2012), anxiety, frustration, depression, and tension as well as to the CR’s well-being (Betini et al., 2017; McConaghy & Caltabiano, 2005; Malhortra et al., 2012). The client’s condition, needs, and personality and the caregivers’ physical, cognitive, social, organizational, and psychological knowledge and skills are some of the factors that impact the care-work (Timonen & Doyle, 2010). The interactions between caregiver and CR include cohesion, satisfaction, and tension, which influence the quality of care as well as the health and quality of life in the care dyad environment (Bom et al., 2019; Tyagi et al., 2019; Wilson et al., 2009).

The relationship between the FDW (in this instance, the caregiver)—who implements the homecare-work—with her employer and the CRs influence the complexity of care provisions (Kehila, 2018; Malhotra et al., 2012; Walsh & Shutes, 2013). The literature confirms that stress can increase the likelihood of occupational burnout, which involves depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, and a sense of low personal accomplishment in the care dyad (Iecovich, 2008; Savage & Bailey, 2004; Shapiro et al., 2007). Unregulated working hours and a wide range of household tasks and care responsibilities can create relational tensions with the employer, leaving FDWs overworked and burned-out (Selkirk et al., 2014). FDWs experience emotional stress and challenges that need support, however, are typically reluctant to seek professional help for psychological difficulties (Selkirk et al., 2014; Wong et al., 2017). This can be due to specific cultural barriers related to a perceived stigma around mental health or a persistent anxiety or even fear of possible repatriation if found ill. Recognizing the important role of FDWs as caregivers and developing training and supervision programs that support the well-being and professional identity of care-workers is crucial for implementing quality care (Kehila, 2020a). Hence, this study suggests that supporting the dyad relationship is a key area for intervention, which can enhance communication and trust, reduce stress and tension, and improve the well-being of both the caregiver and CR.

Theoretical Framework: Mindfulness Approach

Mindfulness is a multifaceted construct that can be understood with multiple frameworks (Pagnini & Phillips, 2015). Studies indicate that mindfulness methods can be useful for stress reduction of people with progressive cognitive decline and their informal caregivers (Collins & Kishita, 2019; Ilali et al., 2018; Kor et al., 2018; Paller et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2016). Inspired by research evidence confirming the benefits of mindfulness on health and well-being, the art therapist (i.e the author), who is a certified yoga therapist, added to the art-based intervention an informal practice of “mindful” lifestyle (Demarzo et al., 2015). This model of mindfulness-based intervention was implemented by an introductory session and a remote and self-guided practice.

Accordingly, the concept of mindfulness was introduced to the care dyad, and basic training was practiced during the first online session, connecting body mindfulness with the practice of creative journaling. The art therapist shared with the caregiver on WhatsApp various links that demonstrate mindful breathing and encouraged participants to try practicing these methods individually and, if applicable, also with the CR in order to develop a mindful lifestyle and awareness of their body sensations, thoughts, and emotional moods (Kögler et al., 2015). The combined practices of artmaking and mindfulness approach of this ABP created complex interventions that helped the participants develop self-reflection as well as understanding of their care needs and ways to benefit from daily artmaking. The participants were invited to reflect on their artmaking experiences as a practice of mindfulness, to independently explore online resources between the sessions, and to expand their knowledge by self-learning. Hence, the mindfulness approach was used not only for developing awareness and reducing stress but also as a framework for the sustainability of the intervention.

The mindfulness approach suggests that the art therapist should be mindful about the multicultural care dyads, their interdependence, and the hierarchical aspect that impacts their complex relationship. The art therapist recognizes the employer as an external stakeholder that influences the care dyad relationship and well-being, the FDW as a professional caregiver and therefore as a collaborator for the program implementation, and both the care dyad as clients that need to be supported by the program.

Methodology and Data Collection

This ABP draws upon a methodological approach of evaluation research using questionnaires, qualitative interviewing, art-based assessments (Brooker & Wooley, 2007; Gavron & Mayseless, 2018; Simons & McCormack, 2007), and observation methods. In order to understand the participants’ experiences, and due to cultural and linguistic variations, as well as their literacy skills, the data collection included one-on-one interviews with the caregivers and post-program questionnaires for caregivers and for employers (family members of CRs). For the CRs, only one CR, who was in her 50s and manifested high cognitive capabilities, was interviewed.

The data collection took place at the homes of the participants, which allowed the art therapists to collect information regarding the context and the care environment and the participants’ daily life. The collected data provide information regarding the CR’s medical conditions, the caregiver’s experience and daily care routine, care relationships within the care dyad and with the CR’s family, and dyad experiences in remote programs that include art appreciation, mindfulness, stress reduction, and communication.

The initial interviews were audio recorded and transcribed soon after each interview. A first feedback questionnaire was conducted after the first online meeting to understand the caregivers’ experiences, which could impact the on-going manner of developing the online part of the program. The post-program questionnaires collected feedback from the caregivers and employers about the program experiences and impact. Caregivers’ reports on their daily engagement in the art activities (with the CR and their own self-care) were added to the artworks’ photographs (visual data) and connected with the participants’ reflections. The artworks were also connected with the therapist’s observations during the process of artmaking, informing the CR abilities and needs as well as the care dyad relationships and communication (see Figure 1 p. 7). The art therapist kept a journal and field notes reports, collecting observations and reflecting on the process, to support the triangulation of data collected in the interviews and questionnaires. An external art therapist assistant helped with checking for reliability of data collection and analysis.

FIGURE 1 | Joint painting procedure.

Participants and Ethical Procedures

Seven dyads allocated by the organization Active Global Specialized Caregivers Singapore (https://www.activeglobalcaregiver.sg/) volunteered to participate in the program. The organization distributed information about the program and helped to recruit participants from their organization’s database of caregivers. Criteria for selection of participants included knowledge of basic English language proficiency of caregivers, basic hand motor skills and cognitive ability of CRs, and basic ability using and access to online communication by the caregiver. Despite the selection criteria, two out of seven participants were very limited in their cognitive functioning, and their participation was compromised. All the CRs are of Chinese ethnicity. The caregivers are from various nationalities such as the Philippines, Myanmar, and Indonesia. All caregivers spoke basic English and were motivated and committed to the program, which contributed to a meaningful collaboration and learning opportunity.

The participants (Table 1) received an information letter describing the program’s goals and activities, the interview procedures, possible risks and benefits for the participants, and assurance of confidentiality. The CRs were represented by their family (adult sons or daughters of the CRs) who consented for their parent’s participation with the employed caregiver. The consent form informed participants of their right to withdraw at any time (during or after the program). With their consent, the participants confirmed the data collection for research and future publications and participation in a final exhibition of selected artworks that represent the program.

FIGURE 2 | Scribbling art by a caregiver.

FIGURE 3 | Collage art by a male care recipient.

TABLE 1 | Participants

| Care recipients |

Caregivers |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Age (years) | Medical condition | Nationality | Duration of work with the care recipient (months) |

| Female | 93 | Dementia; cancer | Filipina | 27 |

| Female | 88 | Dementia | Filipina | 7 |

| Male | 86 | Dementia | Myanmar | 14 |

| Male | 74 | Dementia | Myanmar | 22 |

| Female | 68 | Stroke | Filipina | 16 |

| Male | 61 | Stroke | Indonesia | 25 |

| Female | 56 | Cancer | Indonesia | 7 |

Implementation Process

Seven care dyads were scheduled to start the program beginning on April 1, 2021. The art therapist contacted each employer by WhatsApp to receive the contact information of the caregiver and schedule a date and time to meet at the care dyad’s residence. The therapist maintained weekly communication with the caregivers. In the first session, a basic art materials pack was distributed, with a personal booklet for each participant. The booklet included information about the program and an explanation about some of the tools to be used, introduction and guidance for daily physical activity and mindfulness practice, and a coloring book. During the program, according to the cognitive level and needs of each care dyad, the art therapist provided additional art materials, games, and various accessories.

Approximately, one in three sessions was conducted online. During these sessions, the caregiver led the activity of the care dyad at their home while the art therapist guided the activity online. Between the sessions, the caregivers were offered links to resources and guidance to implementing various artmaking and mindfulness activities. The caregivers were encouraged to practice similar activities with their CRs and to use a personal creative journal for their own reflections and self-care. By the end of the program, participants were offered a token of appreciation for their time, effort, and contribution to the study, and the employers were offered an opportunity to meet online for feedback, debriefing, discussion, and closure.

Results

This study focuses on self-reported experiences by the participants not only as an intervention but also as part of the process of developing one’s mindfulness practice. The concept of mindfulness was explained and demonstrated through body activities and artmaking and practiced by personal reflections (verbal and nonverbal) and artmaking. The ABP introduced daily activities in artmaking to enhance self-expression, provide stress relief, and improve the collaboration and the relationships in the care dyad. The participants’ feedback highlights that artmaking activities were helpful in reducing the stress of the caregiver; improving CR self-esteem, mood, and social interaction; and enhancing the quality of home-based caregiving. The results of the program indicate the meaningful connections between the artmaking and mindfulness approach that influence the experiences of the care dyad through the ABP.

The ABP, with the care dyad as one unit, influenced both the CRs and caregivers to develop their awareness of each other’s experiences, creating a sense of connection and intimacy between them. The use of daily creative journaling (Capacchione, 2015), scribbling (Lee et al., 2019), collage making (Stallings, 2015), coloring books (Barrett, 2015; Mantzios & Giannou, 2018), body movements, and breathing exercises are some of the tools that helped the participants develop mindful communication and relationships that revolve around the artmaking experiences (see photos 2 and 3). As described by one CR, the program influenced her understanding of her caregiver:

(The program) has highlighted to me how I am going to do things with her (pointing at her caregiver who was coming with drinks). It is not only the art that we are doing. Sometimes from the way she drew, I do learn from her as she expresses…I think I understand her more…ahha…I understand more than if she just talks to me. From the way she draws…to know her inner…anything about the day-to-day caring, about her life, things about her family members…

The caregiver’s response emphasizes the meaning of mindfulness added to the artmaking:

I think the additional thing is Mindfulness…you are able to feel your own…capture your own imagination. It’s not like you do it—the art—this is an additional learning in which you are not like doing art…this is the way you do it, or like what makes it more enhanced.

Through the program, the care dyad developed their observations, communication, and understanding of each other. One CR described her understanding of her caregiver’s stress related to the daily tasks and responsibilities:

I asked her: why do you feel stressful? Why don’t you like it (the artmaking)?… then she says, maybe we are not the same, because your mind is focused on the things you want to do now—it is my condition (i.e. medical condition)…and I can’t do the housework…

For me—I am still occupied… and she has to take care of my daily activities, the daily housework, (she) definitely cannot rest as much and enjoy the artwork…that’s the difference between her and me…

Because for me there is nothing much to do…I can enjoy my hobby (i.e. artmaking), for her—she cannot sit down and enjoy this…she needs to think—what else do I need to do after this…so I can understand when she says “a bit stressful”…

Hence, while engaged in self-expression through artmaking, the care dyad could develop their communication and empathy toward each other. Engaged in new activities together, they saw each other in a new perspective, while the art therapist allows some respite time, validating both participants for their challenges and needs.

The feedback analysis highlights the contribution of the ABP to the caregivers’ understanding of artmaking’s application and meaning for the daily care practices. The employers’ feedback indicates that the caregivers were trying new activities with the CR. Based on the cognitive functioning of the CR, both caregivers and employers recognized the contribution of the ABP to the relationship of the care dyad. All the caregivers and employers confirmed that the hybrid structure allowed a good balance between the personal connection and the remote guidance of the art therapist, providing support and encouraging continuing independent practice, facilitated by the caregivers.

Conclusion

The ABP invited the creative spirit and the joy of artmaking into the homes of the participants and encouraged them to add new tools and experiences to their daily activities. The creative-expressive process engages physiological sensations, emotions, and cognition; facilitates verbal and nonverbal symbolization, narration, and expression of conscious or unconscious conflicts and meaning-making through internal and external dialogue and communication between the care dyad. The creative arts and mindfulness framework used in this study foster communication, cooperation and constructive engagement between the CR and the caregiver. The shared activities promoted cultural understanding, empathy, and promoted trusted relationships between the FDW and the Singaporean elderly individuals.

According to the post-program questionnaire, despite the health challenges and limited mobility of the CRs, and for all the FDWs, the engagement with art materials was a stimulating experience. This ABP was innovative not because it raised artistic expectations, but rather because it was applicable to anyone and helped to develop a deep understanding of the impact of artmaking. Creative methods such as scribbling, collage making, visual journaling, and applying mindfulness techniques to daily activities, are all basic tools that may be beneficial to anyone, in enabling self-expression and social connection. The program recognizes the small steps that could be achieved by daily activities in the arts, thereby creating a meaningful contribution to the lives of persons who struggle with health challenges and their caregivers who need support and training in self-care.

Acknowledgments

This project, Art Program for Home-based Care Dyads in Singapore (ref. no. 2021/Art Residency/001), was funded by NUHS Mind Science Centre, Singapore. The author would also like to acknowledge Active Global Specialized Caregivers Singapore for their help in recruiting participants for this program, Prof. Libby Cohen for her advisory and research consultation, art therapist HweeHwee Loo for her assistance in data collection and peer-review, and all the participants and their families, whose support made this project possible and a meaningful learning process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

About the Author

Daphna Arbell Kehila, PhD, is a multimedia artist, adult educator, and a certified expressive art therapist and yoga therapist. She is originally from Israel, where she completed her master’s degree in theatre arts at Tel Aviv University. She later completed an additional Master of Arts in space design from Musashino Art University in Tokyo and a master in expressive arts therapies at Lesley University. She obtained her doctorate degree in adult education from Lesley University in Cambridge, MA.

Daphna has lived with her family in the Asia Pacific region for more than two decades and is a permanent resident of Singapore, where she practices arts and yoga therapies. She supervises art therapy programs for international humanitarian and nongovernmental organizations and develops educational programs for women migrant workers in Singapore. Daphna is passionate about delivering fundamental tools and practices based on the arts that can be applied in the daily lives of care dyads (care recipients and caregivers) to enhance communication and mindfulness skills, well-being, and art appreciation and engagement.

References

Ansah, J. P., Eberlein, R. L., Love, S. R., Bautista, M. A., Thompson, J. P., Malhotra, R., & Matchar, D. B. (2014). Implications of long-term care capacity response policies for an aging population: A simulation analysis. Health Policy, 116(1), 105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.01.006

Au, A., Shardlow, S. M., Teng, Y. U. E., Tsien, T., & Chan, C. (2013). Coping strategies and social support-seeking behaviour among Chinese caring for older people with dementia. Ageing & Society, 33(8), 1422–1441. doi:10.1017/S0144686X12000724

Ayalon, L. (2009). Family and family-like interactions in households with round-the-clock paid foreign carers in Israel. Ageing & Society, 29(5), 671. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X09008393

Barrett, C. A. (2015). Adult coloring books: Patterns for stress relief. Phi Kappa Phi Forum Journal, 95(4), 27.

Beauchet, O., Lafleur, L., Remondière, S., Galery, K., Vilcocq, C., & Launay, C. P. (2020). Effects of participatory art-based painting workshops in geriatric inpatients: Results of a non-randomized open label trial. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 32(12), 2687–2693. doi:10.1007/s40520-020-01675-0

Betini, R. S., Hirdes, J. P., Lero, D. S., Cadell, S., Poss, J., & Heckman, G. (2017). A longitudinal study looking at and beyond care recipient health as a predictor of long term care home admission. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 709. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2671-8

Bloom, D. E., Chatterji, S., Kowal, P., Lloyd-Sherlock, P., McKee, M., Rechel, B., Rosenberg, L., & Smith, J. P. (2015). Macroeconomic implications of population ageing and selected policy responses. The Lancet, 385(9968), 649–657. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61464-1

Bom, J., Bakx, P., Schut, F., & van Doorslaer, E. (2019). The impact of informal caregiving for older adults on the health of various types of caregivers: A systematic review. The Gerontologist, 59(5), e629–e642. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny137

Brooker, D., & Woolley, R. J. (2007). Enriching opportunities for people living with dementia: The development of a blueprint for a sustainable activity-based model. Aging and Mental Health, 11, 371–383. doi: 10.1080/13607860600963687

Campbell, P., Wright, J., Oyebode, J., Job, D., Crome, P., Bentham, P., Jones, L., & Lendon, C. (2008). Determinants of burden in those who care for someone with dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(10), 1078–1085. doi: 10.1002/gps.2071

Capacchione, L. (2015). The creative journal: The art of finding yourself. Ohio University Press.

Carroll, N., Kennedy, C., & Richardson, I. (2016). Challenges towards a connected community healthcare ecosystem (CCHE) for managing long-term conditions. Gerontechnology, 14(2), 64–77. doi: 10.4017/gt.2016.14.2.003.00

Chin, C. W. W., & Phua, K. H. (2016). Long-term care policy: Singapore’s experience. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 28(2), 113–129. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2016.1145534

Colbert, T., & Bent, C. (Eds.). (2018). Working across modalities in the arts therapies: Creative collaborations. New York, NY: Routledge.

Collins, R. N., & Kishita, N. (2019). The effectiveness of mindfulness-and acceptance-based interventions for informal caregivers of people with dementia: A meta-analysis. The Gerontologist, 59(4), e363–e379. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny024

Demarzo, M. M. P., Cebolla, A., & Garcia-Campayo, J. (2015). The implementation of mindfulness in healthcare systems: A theoretical analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 37(2), 166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.11.013

Fancourt, D., & Finn, S. (2019). What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2019 (Health Evidence Network (HEN) synthesis report 67).

Friganovic, A., Selic, P., Ilic, B., & Sedic, B. (2019). Stress and burnout syndrome and their Associations with coping and job satisfaction in critical care nurses: A literature review. Psychiatria Danubina, 31(1), 21–31.

Gaikwad, R., & Warren, J. (2009). The role of home-based information and communications technology interventions in chronic disease management: A systematic literature review. Health Informatics Journal, 15(2), 122–146. doi: 10.1177/1460458209102973

Gavron, T., & Mayseless, O. (2018). Creating art together as a transformative process in parent-child relations: The therapeutic aspects of the joint painting procedure. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2154. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02154

Given, B., Sherwood, P. R., & Given, C. W. (2008). What knowledge and skills do caregivers need? Journal of Social Work Education, 44(suppl. 3), 115–123. doi: 10.5175/JSWE.2008.773247703

Hewko, S. J., Cooper, S. L., Huynh, H., Spiwek, T. L., Carleton, H. L., Reid, S., & Cummings, G. G. (2015). Invisible no more: A scoping review of the health care aide workforce literature. BMC Nursing, 14(1), 38. doi: 10.1186/s12912-015-0090-x

Huang, S., Yeoh, B. S., & Toyota, M. (2012). Caring for the elderly: The embodied labour of migrant care workers in Singapore. Global Networks, 12(2), 195–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0374.2012.00347.x

Iecovich, E. (2008). Caregiving burden, community services, and quality of life of primary caregivers of frail elderly persons. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 27(3), 309–330. doi: 10.1177/0733464808315289

Ilali, E. S., Mokhtary, F., Mousavinasab, N., & Tirgari, A. H. (2018). Impact of art-based life review on depression symptoms among older adults. Art Therapy, 35(3), 148–155. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2018.1531276

Isaksen, L. W., Devi, S. U., & Hochschild, A. R. (2008). Global care crisis: A problem of capital, care chain, or commons? American Behavioral Scientist, 52(3), 405–425. doi: 10.1177/0002764208323513

Kehila, D. A. (2018). Developing and managing knowledge and practice of care-giving: The case of Filipina domestic workers in Singapore. Doctoral dissertation, Cambridge Massachusetts: Lesley University.

Kehila, D. A. (2019). Leadership: Filipina domestic workers volunteer to teach care-giving. COABE Journal, 8(2), 4–21.

Kehila, D. A. (2020a). Becoming care workers. In S. L. Motulsky, J. A. Gammel, & A. Rutstein-Riley (Eds.). Identity and lifelong learning: Becoming through lived experience (p. 109). North Carolina: Information Age Publishing.

Kehila, D. A. (2020b). Caregivers’ education in global time: The case of Filipina domestic workers in Singapore. In J. P. Egan (Ed.). Proceedings of the Adult Education in Global Times Conference (pp. 350–358). Vancouver, B.C: University of British Columbia.

Kögler, M., Brandstätter, M., Borasio, G. D., Fensterer, V., Küchenhoff, H., & Fegg, M. J. (2015). Mindfulness in informal caregivers of palliative patients. Palliative & Supportive Care, 13(1), 11–18. doi: 10.1017/S1478951513000400

Kor, P. P., Chien, W. T., Liu, J. Y., & Lai, C. K. (2018). Mindfulness-based intervention for stress reduction of family caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 9(1), 7–22. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0751-9

Kirsty-Bennett, K., & Arbell-Kehila, D. (2021). Art therapy with foreign domestic workers in Singapore. In V. Huet & L. Kapitan (Eds.). International advances in art therapy research and practice: The emerging picture (pp. 224–232). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Lee, R., Wong, J., Shoon, W. L., Gandhi, M., Lei, F., Kua, E. H., Rawtaera, I. C. & Mahendran, R. (2019). Art therapy for the prevention of cognitive decline. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 64, 20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2018.12.003

Levine, C., Halper, D., Peist, A., & Gould, D. A. (2010). Bridging troubled waters: Family caregivers, transitions, and long-term care. Health Affairs, 29(1), 116–124. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0520

Malhotra, C., Malhotra, R., Østbye, T., Matchar, D., & Chan, A. (2012). Depressive symptoms among informal caregivers of older adults: Insights from the Singapore Survey on Informal Caregiving. International Psychogeriatrics, 24(8), 1335–1346. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212000324

Mantzios, M., & Giannou, K. (2018). When did coloring books become mindful? Exploring the effectiveness of a novel method of mindfulness-guided instructions for coloring books to increase mindfulness and decrease anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 56. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00056

McBee, L., & Bloom, P. (2016). Is aging a disease? Mental health issues and approaches for elders and caregivers. In E. Shonin, W. Gordon, & M. Griffiths (Eds.), Mindfulness and Buddhist-derived approaches in mental health and addiction. Advances in Mental Health and Addiction (pp. 337–362). Cham: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22255-4_17

McConaghy, R., & Caltabiano, M. L. (2005). Caring for a person with dementia: Exploring relationships between perceived burden, depression, coping and well-being. Nursing & Health Sciences, 7(2), 81–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2005.00213.x

Mehta, K. K., & Leng, T. L. (2017). Experiences of formal and informal caregivers of older persons in Singapore. Journal of Cross-cultural Gerontology, 32(3), 373–385. doi: 10.1007/s10823-017-9329-1

Muyskens, K. (2020). Will Confucian values help or hinder the crisis of elder care in modern Singapore? Asian Bioethics Review, 12, 117–134. doi: 10.1007/s41649-020-00123-5

Østbye, T., Malhotra, R., Malhotra, C., Arambepola, C., & Chan, A. (2013). Does support from foreign domestic workers decrease the negative impact of informal caregiving? Results from Singapore survey on informal caregiving. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68(4), 609–621. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt042

Pagnini, F., & Phillips, D. (2015). Being mindful about mindfulness. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(4): 288–289. doi: S2215-0366(15)00041-3

Paller, K. A., Creery, J. D., Florczak, S. M., Weintraub, S., Mesulam, M. M., Reber, P. J., Kiragu, J., Rooks, J., Safron, A., Morhardt, D., O’Hara, M., Gigler, K. L., Molony, J. M., & Maslar, M. (2015). Benefits of mindfulness training for patients with progressive cognitive decline and their caregivers. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & OtherDementias, 30(3), 257–267. doi: 10.1177/1533317514545377

Piau, A., Wild, K., Mattek, N., & Kaye, J. (2019). Current state of digital biomarker technologies for real-life, home-based monitoring of cognitive function for mild cognitive impairment to mild Alzheimer disease and implications for clinical care: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(8), e12785. doi: 10.2196/12785

Quinn, W. V., O’Brien, E., & Springan, G. (2018). Using telehealth to improve home-based care for older adults and family caregivers. Insight on the Issues 135. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute.

Quinn, C., Clare, L., McGuinness, T., & Woods, R. T. (2012). The impact of relationships, motivations, and meanings on dementia caregiving outcomes. International Psychogeriatrics, 24(11), 1816–1826. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212000889

Savage, S., & Bailey, S. (2004). The impact of caring on caregivers’ mental health: A review of the literature. Australian Health Review, 27(1) 111–117.

Savazzi, F., Isernia, S., Farina, E., Fioravanti, R., D’Amico, A., Saibene, F. L., Rabuffetti, M., Gilli, G., Alberoni, M., Nemni, R., & Baglio, F. (2020). “Art, colors, and emotions” treatment (ACE-t): A pilot study on the efficacy of an art-based intervention for people with Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1467. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01467

Selkirk, M., Quayle, E., & Rothwell, N. (2014). A systematic review of factors affecting migrant attitudes towards seeking psychological help. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 25(1), 94–127. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0026

Shapiro, S. L., Brown, K. W., & Biegel, G. M. (2007). Teaching self-care to caregivers: Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the mental health of therapists in training. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 1(2), 105. doi: 10.1037/1931-3918.1.2.105

Skirrow, P., & Hatton, C. (2007). ‘Burnout’ amongst direct care workers in services for adults with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review of research findings and initial normative data. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20(2), 131–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2006.00311.x

Simons, H., & McCormack, B. (2007). Integrating arts-based inquiry in evaluation methodology: Opportunities and challenges. Qualitative Inquiry, 13(2), 292–311. doi: 10.1177/1077800406295622

Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Karazsia, B. T., & Myers, R. E. (2016). Caregiver training in mindfulness-based positive behavior supports (MBPBS): Effects on caregivers and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, article 98. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00098

Slocum-Gori, S., Hemsworth, D., Chan, W. W., Carson, A., & Kazanjian, A. (2013). Understanding compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and burnout: A survey of the hospice palliative care workforce. Palliative Medicine, 27(2), 172–178. doi: 10.1177/0269216311431311

Stallings, J. W. (2015). Collage as an expressive medium in art therapy. In D. E. Gussak & M. L. Rosal (Eds.). The Wiley handbook of art therapy (pp. 163–170). New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell.

Suen, J., & Thang, L. L. (2018). Contextual challenges and the mosaic of support: Understanding the vulnerabilities of low-income informal caregivers of dependent elders in Singapore. Journal of Cross-cultural Gerontology, 33(2), 163–181. doi: 10.1007/s10823-017-9334-4

Teo, Y. (2017). The Singaporean welfare state system. In C. A spalter (Ed.). The Routledge International Handbook to Welfare State Systems (pp. 383–397).

Thompson, J., Malhotra, R., Love, S., Ostbye, T., Chan, A., & Matchar, D. (2014). Projecting the number of older Singaporeans with activity of daily living limitations requiring human assistance through 2030. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 43, 51–56. https://www.annals.edu.sg/pdf/43VolNo1Jan2014/V43N1p51.pdf

Timonen, V., & Doyle, M. (2010). Migrant care workers’ relationships with care recipients, colleagues and employers. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 17(1), 25–41. doi: 10.1177/1350506809350859

Tyagi, S., Koh, G. C., Luo, N., Tan, K. B., Hoenig, H., Matchar, D. B., Yoong, J., Chan, A., Lee, K. E., Venketasubramanian, N., Menon, E., Chan, K. M., De Silva, D. A., Yap, P., Tan, B. Y., Chew, E., Young, S. H., Ng, Y. S., Tu, T. M., Ang, Y. H., Kong, K. H., Singh, R., Merchant, R. A., Chang, H. M., Yeo, T. T., Ning, C., Cheong, A., Ng, Y. L., & Tan, C. S. (2019). Dyadic approach to post-stroke hospitalizations: Role of caregiver and patient characteristics. BMC Neurology, 19(1), 267. doi: 10.1186/s12883-019-1510-4

Walsh, K., & Shutes, I. (2013). Care relationships, quality of care and migrant workers caring for older people. Ageing & Society, 33(3), 393–420. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X11001309

Wong, M. H. M., Keng, S. L., Buck, P. J. B., Ostbye, T., Wessels, A., & Suthendran, S. (2017). Mental health paraprofessional training for Filipina foreign domestic workers in Singapore: Feasibility and effects on knowledge about depression and cognitive behavioral therapy skills. European Psychiatry, 41(S1), S626–S626. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.1014

Wilson, C. B., Davies, S., & Nolan, M. (2009). Developing personal relationships in care homes: Realising the contributions of staff, residents and family members. Ageing & Society, 29(7), 1041–1063. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X0900840X

Woods, O., & Kong, L. (2020). New cultures of care? The spatio-temporal modalities of home-based smart eldercare technologies in Singapore. Social & Cultural Geography, 21(9), 1307–1327. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2018.1550584