Creating Worlds: Well-Being through Japanese Otome Bunraku

创造世界:日本乙女文楽带来的幸福感

Caroline Astell-Burt

London School of Puppetry, UK

Abstract

There is a type of puppet animation that appeared to suggest itself as a therapeutic medium at the London School of Puppetry. However, the repair of emotional chasm with new health, which might be physical, mental, or spiritual, was not what was intended. The school was offering an introduction to an artistic phenomenon from Japan called otome bunraku or “maiden’s doll theater,” but common to all participants, the result of performing this type of puppetry was an unexpected and profound sense of well-being. This feeling challenges anything the puppet alone offers to a puppeteer, and as an alternative, points to other possibilities of focusing on the puppeteer instead as a playfully disruptive, interruptive, creative, expressive and skillful presence. It argues that the nature of the puppeteer’s presence revealed in otome bunraku is a unified mind and body manifested in the manipulation of these puppets. A person reaches a physical and social realization of what well-being means through an experience of “being other” and therefore by creating other worlds in the process of puppetry.

Keywords: puppeteer, puppetry, otome bunraku, well-being, other, phenomenology, body

摘要

在伦敦木偶学院, 有一种木偶动画将其视作一种治疗媒介。然而, 以新的健康状态(可 能是身体、心理或精神上的健康)来修复情感鸿沟并不是其目的。学院对来自日本的 被称为乙女文楽或“少女的玩偶剧场” 的艺术现象进行了一次介绍, 参与者们普遍认 为, 表演这种木偶戏能够给人带来一种意想不到的、深刻的幸福感。这种感觉是对木偶 本身给予木偶师的任何东西的挑战, 作为一种替代, 它指向了关注木偶师身上的其他可 能性, 而不是作为一种有趣的破坏性、干扰性、创造性、表现性和技巧性的存在。文章 认为, 在乙女文楽中所揭示的木偶师存在的本质是在操纵这些木偶时表现出的统一的思 想和身体。一个人通过“成为他者” 的体验, 并因此通过在木偶戏的过程中创造其他 世界, 在身体和社会层面上实现对幸福含义的认识。

关键词: 木偶师, 木偶戏, 乙女文楽, 福祉, 他者, 现象学, 身体。

Introduction

Otome bunraku is an unusual form of puppetry and a description about it was first introduced to the West by Dr Darren Ashmore at Sheffield University in his 2005 article “Kiritake Masako’s Maiden’s Bunraku.” but ten years passed before its practice came to Europe in the training work of the London School of Puppetry.

Significantly, in this type of performance, the puppet is attached to the body of the operator at the head, waist, knees, and arms with movement being projected into the puppet as an echo of the original human motion. When the puppeteer’s head moves, the puppet head moves, likewise for all limbs. The head movement is significant, producing the illusion of vitality in the puppet. Although puppetry was acknowledged by the participants as having therapeutic value and commented on their wellness, the author is a professional puppeteer and not a therapist. As a contribution to research, over several years, sessions were run for challenging teenagers, university students, and specific wellbeing courses for women in France and in the UK.

This article asks how the otome bunraku puppet can be a therapeutic tool used in activity to promote health and psychological well-being. In reply it aims to introduce to the reader theoretical aspects of puppetry embodied in otome bunraku. There are five concepts to consider: “withness,” space, presence, “being other,” and the unification of the body and mind.

“Withness”

The therapeutic process in puppetry is not only about the dolls, (especially NOT the making of them) but the inseparable, performative and co-present combination of puppeteers, puppets, and spectators. “Withness” is a theoretical term recently invented to describe the puppetry process (Astell-Burt et al., 2020). The combination of a creative psychiatric nurse, Theresa McNally and the author, initially developed the concept of creative spectating that they identified in people living with very advanced dementia. These individuals drew on the remnants of emotional memory to respond to the puppets solely from the perspective of someone watching puppetry. This convinced the researchers of the universal validity of spectating as one of the creative aspects of puppetry. Seeing the Japanese otome bunraku puppeteer co-present with the puppet enables the spectator to validate themselves kinaesthetically inside the artist’s performance of the puppet object (Figure 1a).

FIGURE 1 | (a) Michiko Ben operating a puppet. The intensity of her performance shows how the artist’s performance is manifested equally in the materials, the operating technique, and her own corporeality. (b) Performance inside a giant version of otome bunraku with only legs and feet revealed.

Co-presence is also proclaimed in an example when only the legs and feet of a puppeteer are visible below the puppet (Figure 1b). In her regular performances of a giant adaptation of otome bunraku in which she was semi-concealed, a woman with schizophrenia, said that she gained a sense of utter peace and creative satisfaction, “more than she had ever known in her 65 years.” Feeling invisible enabled the woman to become unusually responsive and communicative dancing ‘with’ the delighted street audience (Astell-Burt: unpublished artists notes 2012).

Space for performance

Puppetry originates in various spaces. Large and small. These might be actual places where a sense of well-being might initially be found but must also be located internally in spiritual or emotional modes and expressed externally unified in the body. One young puppeteer, an electively mute child found comfort and a voice by making a space for hiding behind a screen or inside a puppet booth from where he sang with his puppet and called out. (Astell-Burt, 1981, p. 103) McNally developed a celebratory puppet theater in a shared space where the showing to, or sharing with, happened in a small, special room (Astell-Burt et al., 2020). She also performs at the bedsides of residents of a care-home. It is a phenomenological embracing of well-being as a lived experience of presence through the puppet, on the part of both spectators and puppeteers.

Moving into presence

Puppet animation creates such a rich and complex presence because ultimately, the nature of puppetry is relational. The puppeteer works from a position of mutual welcoming and enjoyment through performance. Liberating the imagination to operate the puppet is activity which at the same time further stimulates the puppeteer’s imagination creating a sensory beneficial loop. The participant could be any individual using puppetry while on a personal journey to discover a positive state of mind, enabling them to function as they want to in society. This socialization of the emotions brings the lived self into place in the group. Well-being in puppetry is the way a person is brought into a sense of their presence by means of their bodies and emotions either by performing the puppets or, if watching by means of the kinesthetic experience of spectating. It is recognized that puppetry uses an existing link between emotion and the somatic disposition of a person with their images, thoughts, and memories—a cooperation of which the individual is increasingly aware.

Being other

To project oneself into the puppet is the opportunity to explore thoughts, feelings, fantasies, fears and desires and to “own” internal puppet-space and to make sense of subjective experience as “other”. Such revelation might be sheer enjoyment, or make one “feel good” by becoming increasingly self-aware by plunging into the otherness of the puppet role. Gaining self-awareness could be a significant step towards change. Participants coming to puppetry to achieve a sense of well-being are often unsure of any negative attitudes to their emotions and whatever they care about. To some degree, the puppet works as a calming, focused, created other, allowing the participant to begin to feel safe.

Unification of the body, mind, and spirit

In the need for a search for well-being, being unwell is the neglect of the body as the combination of the physical, emotional and spiritual. Otome bunraku puppet movement as a dance-like discipline demands the visible presence of the puppeteer working imaginatively and reflectively to heal the body and mind of the effects of the Cartesian disciplines and its mind/body split. This split deeply shaped Western thought and contributes to the absenting or disregard of the body and displacing the emotions in favor of unesthetic “rational thought.” “Neglect of emotions lies deeply buried in Western thought, a tradition which historically has sought to divorce body from mind, nature from culture, reason from emotions and public from private” (Williams & Bendelow, 1998, n.p.). These worrying splits might lie at the heart of deep inner confusions, especially because they are gendered, whereby rationality is supposed to be masculine, but emotions are feminine and irrelevant. Emotions are “lived” and embodied, the body being the physical structure of those emotions. Such emotions are not something soft and unnecessary, but they are intellectual, knowledgeable and of social and moral value to be lived “socially and reflectively” (Denzin, 1984, p.28). Otome bunraku as a therapeutic tool challenges intellectual and emotional neglect by the use of the body. By taking an approach informed by the phenomenology of primarily Japanese thinkers, the aim of art to integrate processes of the “lived body” is explored and a non-rational esthetic approach to puppetry and well-being adopted to enhance the value of the emotions by means of mutual intentionality.

How does mutual intentionality in puppetry create a sense of well-being? The Western view of puppetry is by means of empirical observation of mental and bodily phenomena. For Ichikawa Hiroshi the Japanese philosopher, the making of the puppet object would not to be the central aim of puppetry but instead the compilation of bodily energies all involved in their different forms; physical, or dramatic. (Ichikawa, 1993: 186–7). He is suggesting here two important themes. The first is the integrated nature not only of mind and body, but equally of life and art, a view which itself arises from traditional Japanese aesthetics. The second is that, while Western thinkers tend to see ‘discipline’ as subjection and bodily control, which they link to asceticism, Japanese thinking tends to see bodily practice as cultivation, seeking as its end not power, but the recognition of mind-body integration. Thus, the observer would be interested in the connections to be made between the mental intention to lift or hold the puppet and the associated somatic understanding of the techniques of moving the puppet. However, empirical observation is limited in practice because there are some aspects of the activity that cannot be observed; they are unseen. The mystery of the puppet “coming to life” is not a scientific event, as it cannot show observable signs of life as empirical evidence, and yet we enjoy the experience as imaginative activity. The Japanese perspective on the “lived body” looks at the relationship between the theoretical premise behind the practice of puppetry, the somatic practice, and the integration of theory and practice as artistic achievement (Ozawa-de Silva, 2002, p. 35). Therefore, the artistic achievement of the spectator, puppeteer relationship can come about as unseen, but the results validated by the feeling of satisfaction expressed by the schizophrenic woman above.

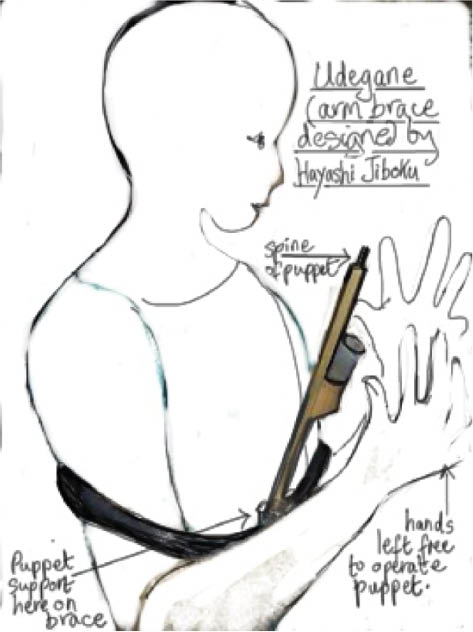

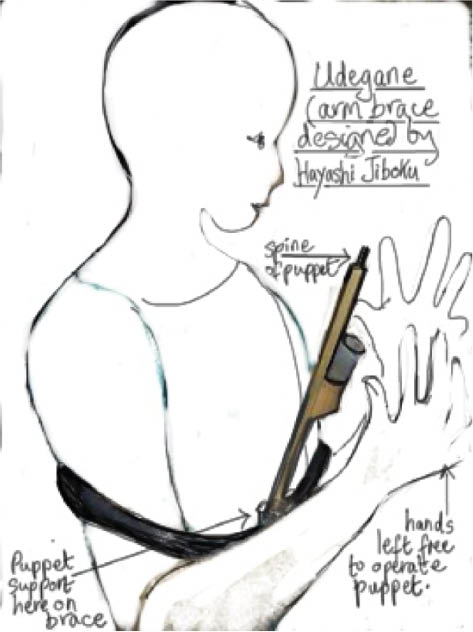

Japanese otome bunraku: the first UK workshop

The Japanese puppeteer, Yuki Kudo, introduced otome bunraku to the London School of Puppetry in 2010. She took a group through a process of making roughly finished, unfamiliar puppets that are, unusually, attached to puppeteers’ heads, waists, and knees (Figure 2). The puppet is held up by a kind of brace called udegane, which was a metal coil or wire twisted around the upper arms of the puppeteer joined at the center to form a spigot in front of the chest onto which the puppet was slotted (Figure 3). This was later replaced with a dogone brace that held the weight of the puppet on the waist (Figure 4). Positioned like this, either brace allowed the puppet to float apparently unsupported in front of the puppeteer. Bare-faced and “inhabiting” the inert stuff of the puppet, otome bunraku offered to the puppeteer what became a performative bodily presence (Figure 5).

FIGURE 2 | Participants with otome bunraku puppets.

FIGURE 3 | Udegane: a coil of metal twisted around the upper arms of the puppeteer, leaving the lower arms free to operate the hands of the puppet.

FIGURE 4 | Puppeteer with a simple dogone support for the puppet on the waist.

FIGURE 5 | Kiritake Masako operating otome bunraku puppet in the 1930s. Photo permission from Darren Ashmore.

The puppeteer creates movement for the puppets that is expressed through dancelike motions and ever-subtle moves of the hands, legs, head, and neck. The puppets “become movement” giving rise to these comments:

Comments from the participants

“In our excitement, we experienced an incredible sense of self in these strange puppets. It was as if the individual presence of each puppeteer crystallised into a fusion of materials, energy and imagination becoming a new entity of puppeteer-with-puppet.”

“As we took turns watching, we quickly gathered that puppetry has an existence outside the theatre, that not being solely theatrical things, the puppet objects themselves had meaning beyond their material presence—a way of enveloping us.”

“The style and materials of the puppets, the way we danced with them, inhabited space with them, and primarily the relationship they had to our bodies made a particular impression on me feeling good—my well-being.”

“So we didn’t have to make a story or play, just to be. I loved my puppet friend!”

Conclusions from the workshops

Because of the proximity of the puppet, participants were able to “hide.” They were successfully engaging the puppet as a surrogate for themselves to tell personal stories or simply to move or dance to music. They could become “other.”

Although puppetry is a performance art, commonly found in all kinds of theater, it is rooted not in theater but in the world of objects and our relationships with them such as how they are owned and treasured. The control the puppeteer has over the puppet object, which is inanimate, produces a feeling of achievement and completion. The object is a dead thing. The healing process in puppetry lies in satisfying the desire to play with puppets as if they are alive despite the knowledge that they are not. Making them seem alive empowers the puppeteer (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6 | The healing process in puppetry lies in satisfying the desire to play with puppets as if they are alive despite the knowledge that they are not.

In puppetry, there can be no active-subject/passive-object relationship of puppeteer to puppet, but rather the creation of a puppet-subject or surrogate giving presence to the puppeteer and also protection to “speak out” and say anything through the puppet. The moment of giving up subject-hood and handing it to the puppet-object is one that can be profoundly moving to the participant as a type of off-loading. This dead thing is so completely “other,” therefore “not me,” that giving it an appearance of life shared with a spectator provides reward to everyone.

The puppet can be used to embody characterizations from the participants stories by working with transferences and projective identifications. One puppeteer used a human-sized witch-type puppet to play her own mother, who she remembered as mouthing, and critical towards her. By performing an imitation with the puppet, she achieved insight about her parent and a degree of sympathy realizing that the mother’s need to criticize was pathetic and not to be feared. However, here, it is important that we do not simply replay and repeat the social realism of the participant’s life. Using puppets offers a creative, possibly bizarre, and exploratory opportunity to experience a new way of being and different outcomes. A puppet can be anything and acting out through a range of characters can both release the puppeteer, and creating touching comedy and insights.

Bodily presence

There is a sense in which anyone might need to be convinced that they have a presence as an individual and that they can be a cause of something positive in everyday life. Puppetry therefore offers an enhanced presence, a nudge to the memory that “I have a right to be here, occupying space.” In a sense, a puppeteer has two bodies, their own and the puppet, so they are doubly present. An inability to have presence as an individual is one that throughout history, puppeteers have been denied.

The history of puppetry plays with the question of the effects of the visible presence of the puppeteer of whatever gender, and often, the question is not based on artistic truths but contemporaneous ideas about respectability or prejudice. The visible presence of the puppeteer strikes out against moves to prevent empowerment and freedom of expression. Ultimately, the visible presence of the otome bunraku puppeteer exclaims the well-being brought about by a sense of being here, moving and flowing and making a performance space. The question about whether the puppeteer should be visible can be controversial. Female puppeteers from seventeenth-century Japan and the antecedents of otome bunraku were banned from theaters and found an existence in the underbelly of respectability in the Japanese pleasure districts. English puppeteers in the same period were typically to be found in London’s Bartholemew Fair, an ancient cloth market and scene of illicit activity. The play of that name by Ben Jonson was first staged in 1614 and included an amusing action of a puppeteer who shockingly raised the puppet’s long smock to reveal his own naked hand proving to a heckler that the puppet had no sex and therefore could not be guilty of the immoral act of cross-dressing (Act IV, Scene iii). Hand puppets are operated from below so that if a costume was lifted, the naked hand of the concealed puppeteer would have shown.

Long before that, writing in 445 BC and giving us the earliest reference to puppeteers and puppets in the ancient Western world, the historian Herodotus describes the female Greek neurospasta (string pullers), who had replaced the parading of a large statue of a phallus with the much livelier and comic puppet performance of a string being pulled to raise a puppet-penis. He writes:

The rest of the festival of Dionysius is ordered by the Egyptians much as it is by the Greeks, except for the dances; but in place of the phallus they have invented the use of [naked] puppet [men] a cubit high, moved by strings, which are carried about the villages by women, the male member moving and near as big as the rest of the body. (Godley, 1920, Book 2.48.2)

These examples demonstrate to the spectator both the visible and the concealed puppeteer. The former example effectively ridiculed that popular idea that the puppet is a living thing, requiring puppeteers to stay out of view to sustain the illusion. By showing a cheeky glimpse of the puppeteer being present, the illusion is spoiled. In the latter example, temple prostitutes were completely visible and performed a sexy joke that advertised their presence as manipulators. Both examples obliterate the autonomy of the puppet-characters to reflect instead on the puppeteer-with-puppet.

Reflection on those historical examples of puppetry reveal that it is in the nature of puppeteer presence to disrupt or interrupt any concept of realism in play with objects. Puppets are inanimate objects that do not come to life, but do become movement. Not only do performances produce enjoyment but so does the visible, interruptive presence of puppeteers executing their craft of giving movement to the inanimate. Otome bunraku puppeteers are seen physically operating puppets that reflect qualities and aliveness without imitation or realism. The nature of puppeteer presence is to interrupt “realism” and to insist that the spectator look again, and therefore, any life in the puppet is a projection of the spectator’s imagination and reflects the presence of the puppeteer.

Spectators know that the puppet is an inanimate thing because however lifelike, the interrupting presence of the puppeteer either subverts in the case of Jonson or overtly reminds the spectator that the puppet has no autonomy in the observation provided by Herodotus.

In the case of otome bunraku, the puppeteer is clearly seen operating. The puppet head is attached to the puppeteer’s head. When the puppet is operated, although the spectators know what it is (an inanimate object), in the hands of the puppeteer, it becomes something that affects the audience emotionally. It embodies the perceptions of the spectator and puppeteer in a mutual intentionality.

Operating the otome bunraku puppet: technique

Although the otome bunraku puppet is worn by the puppeteer, and therefore they are very close together, so close that the puppet might be referred to as a second body. To operate the puppet, the puppeteer has to adopt a posture that maintains space between those bodies. Such space is both physical and philosophical, representing both the breath of the puppeteers and producing space between them and their puppets, or the “radiant, invisible body of air,” as Luce Irigaray writes in The Forgetting of Air in Martin Heidegger. This air keeps the puppeteer and the puppet separate:

The flesh unfurls its flowerings, holding nothing back. Radiant, invisible body of air. The look’s every embrace finds there the heaven of its light … rendering impossible their penetration into each other. (1999, p. 117)

The need to retain that impenetrable separateness allows the signification of the materially inanimate puppet to be achieved. It is possible to develop an intense consciousness of the puppet made into expressive consummate moments that are derived from the body of the puppeteer. There will always be the living body of the puppeteer and the puppet will always be that other body, an artifact, something found and adopted or made. (Barba & Savarese, 1991, p. 9) The spectator chooses to see something not alive, not entirely dead because of certain imaginary simulations, but “undead” as another body. The spectator need not refer back to the living body of the puppeteer but persist in relating to the puppet in which we find “a paradoxical incorporation … not by returning to the living body from which ideas and thoughts have been torn loose, but by incarnating the latter in another artifactual body” (Derrida, 1994, p. 126). In this way, the separateness of the puppeteer and puppet persist and yet are philosophically complete in a working presence to each other as the compilation mentioned above. What is particularly effective is that the otome bunraku puppet is a “second body.” The puppeteer’s body is fully engaged, covered up yet visible, artistically viable but humanly vulnerable. This human vulnerability is displaced for a moment into the puppet. By manipulating the puppet as a transitional object, a version of the puppeteer is imprinted into its form, occupying it and energizing it. This is transformative for the puppeteer. Notions of the performing body are subverted and replaced by a kind of psychological vagrancy whereby the puppeteer can “enter” and “leave” the puppet “body” at will. In such a particular spatial revelation, the puppeteer and spectator indulge in a transformative practice, an “incredible effort of re-materialising … moving so fast between the quick and the dead,” as Herbert Blau (1982, p. 199) puts it. The sensory experience that this affords points to the crux of therapeutic puppetry. The puppeteer and spectator are drawn into the fictional “consciousness” of the puppet to promote well-being.

To operate the rare and beautiful Japanese otome bunraku puppet, the limbs and puppet’s head are attached to the puppeteer: head tied to the head, arms to arms, body to body, legs to legs. They share close proximity—the puppet is carried in front of the puppeteer, making the puppeteer “pregnant,” with potential moves out into space in mirror reflections of motion. The technique of puppetry is based on interruption by “unfamiliarity.” Equally, in otome bunraku, the puppeteer is physically present but additionally made known by the interruption of the “normal” by strings from the head of the puppeteer to the head of the puppet (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7 | The puppeteer is physically present but additionally made known by the interruption of the “normal” by obvious strings from the head of the puppeteer to the head of the puppet.

Returning to the idea of the puppeteer and spectator finding presence in the performance of the puppet, there is an experience of shared space and shared embodiment of physicalities and thoughts. A concept of embodiment would overcome the dichotomy between the body as an object of an ideology and the body as an experiencing subject. The phenomenological “lived body” might repair a gap produced by separating the social and intellectual from the physical body. “Providing a phenomenological context proposes a consideration of human bodies who at the moment of performance, do more than perform and are material, tool, subject and source within a singular event” (Sanchez-Colberg & Preston Dunlop, 2010, p. 173).

The practice of otome bunraku demonstrates not only performance, but the body as the originating source of that expression in an object supported by a particular operating technology (strings, rods, jointing, etc.). As a methodology that originates in Japan, and is therefore non-Western, Japanese puppetry provides, along with technique, a developing notion of puppeteer presence. Rather than the philosophical silencing of the puppeteer’s body, sociologies of Japanese puppetry offer unique theoretical and methodological contributions to build upon in two different ways: their contemplation on body–mind unity as a goal of their art, and the way art and culture are included in the everyday to give credence to the puppeteer’s work. The puppeteer transcends the materiality of the puppet and their own material presence to achieve a performance. It is further explained by Merleau-Ponty who writes, “between seeing and being seen, touching and being touched which means that like a surreal half presence, things pass into us and we pass into things” (1968, p. 165). Whereas some might see the body as solely determined by biological, mechanical, and physiological processes as against the processes of thought, mind, imagination, and so on, puppetry cancels this dualism by locating consciousness in bodily process, founded in perception with an active, purposeful intentionality and thus well-being.

Well-being through Japanese otome bunraku

Otome bunraku reveals that in the visible presence of the puppeteer, the puppet theater is seen typically as a theater of fragments, the puppet shadowed by the puppeteer, both faces next to each other, semi-obliterations and ambiguities that leave the spectator free to complete the whole. The otome bunraku puppeteer demonstrates an awareness of the comic, poetic, and emotional aspects of the performance and plays accordingly, tenderly or with bold certainty to “create worlds with the spectator.” “The creation of worlds so beautifully achieved in otome bunraku passes to all puppeteers an emblematic value, suggesting realities beyond the here and now” of the performance where the needs of the participant lie in expectation. The mysterious alchemy that surrounds the interplay between spectators and puppeteers produces poetic resonances that go far beyond technique offering in their wake a sense of healthy being.

About the Author

Caroline Astell-Burt is a professional puppeteer who has also pioneered work in the art of puppetry in education and therapy. She started performing and writing about puppetry in 1977. She is an enthusiastic authority on puppetry in education and therapy. She and colleague, Ronnie Le Drew, set up the first UK training school for professional puppeteers in 1987. She has masters’ degrees from Middlesex and Royal Holloway and a PhD from Loughborough. She is affiliated with the London School of Puppetry, where Japanese otome bunraku has been researched and practiced as an art form from 2010 and as well-being experience for women since 2019. London School of Puppetry, 2 Legard Rd, London, N5 1DE. E-Mail: castellburt@londonschoolofpuppetry.com. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2605-990.

Conflicts of Interest

No known conflict of interest to disclose.

References

Ashmore, D. (2005). Kiritake masako’s maiden’s bunraku. Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies. http://www.japanesestudies.org.uk/articles/2005/Ashmore.html. Accessed November 7 2015.

Astell-Burt, C. (1981). Puppetry for mentally handicapped people. England: Souvenir Press.

Astell-Burt, C., Collard-Stokes, G., Irons, Y., & McNally, T. (2020). ‘Withness’: Creative spectating for residents living with advanced dementia in care homes. Journal of Applied Arts & Health, 11, 125–133.

Barba, E., & Savarese, N. (1991). A dictionary of theatre anthropology: The secret art of the performer. England: Routledge.

Blau, H. (1982). Take up the bodies. Theatre at the vanishing point. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Denzin, N. K. (1984). On understanding emotion. California: Jossey-Bass.

Derrida, J. (1994). Spectres of marx. London: Routledge.

Godley, A. D. (Trans.) (1920). The histories. Book 2.48.2. Retrieved December 1, 2016, from http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text.

Ichikawa, H. (1993). Mi no Kôzô [Structure of the body: Overcoming the theory of the body]. Tokyo: Kôdansha Gakujutsu Bunko.

Irigaray, L. (1999). The forgetting of air in Martin Heidegger (M. B. Mader, Trans.). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1968). The visible and the invisible (C. Lefort, Ed.; A. Lingis, Trans.). Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Ozawa-De Silva, C. (2002). “Beyond the body/mind?” Japanese contemporary thinkers on alternative sociologies of the body. Body & Society, 8(2), 21–38. New Delhi: Thousand Oaks. http://bod.sagepub.com/content/8/2/21. Accessed 23rd July 2016.

Sanchez-Colberg, A., & Preston Dunlop, V. (2010). Dance and the performative. Binsted, UK: Dance Books Ltd.

Williams, S. J., & Bendelow, G. (1998). The lived body. London, New York: Routledge.