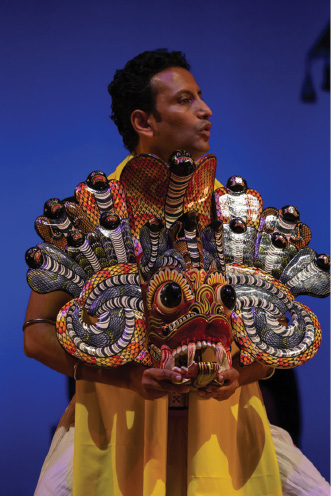

FIGURE 1 | The author performing in the ‘Masks and Myths: Devils and Dancers from Sri Lanka’ event at the Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts, Chicago, October 2018, photos by Tom Rossiter.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2021) 7(2):149–157 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2021/7/20 |

Decolonizing Dance Movement Therapy: A Healing Practice Stuck between Coloniality and Nationalism in Sri Lanka

舞蹈/动作治疗的去殖民化:困于斯里兰卡殖民主义和民族主义之间的疗愈实践

Department of Fine Arts, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka

Abstract

Dance therapy or dance/movement therapy (DMT) in the modern sense is relatively new to Sri Lanka. Recently, there has been an interest in establishing it as a profession on the island. As DMT is in the very early stages in the country, I see the different directions that it can take. As a dancer, dance educator, and researcher, I see the importance and the potential of healing aspects of dance and movements. However, as an emerging discipline, I demonstrate that at least three directions that DMT in Sri Lanka could take—colonial, nationalized, and decolonial. My premise is that DMT becomes colonial, given its history and orientation, when it is introduced to a postcolonial site. As I argue, DMT imposes a particular colonial framework when introduced to a postcolonial site like Sri Lanka. At the same time, some try to frame DMT in an ethno-nationalist discourse by attempting to prove that dance therapy has already existed in Sinhala traditional ritual practices. Focusing on Sri Lanka, this article questions these colonial and nationalized approaches in DMT and suggests that a decolonial approach is possible.

Keywords: decolonial, dance movement therapy, Sri Lanka, coloniality, nationalism

摘要

现代意义上的舞蹈治疗或舞蹈/动作治疗 (DMT) 在斯里兰卡是较新的领域。近来, 人们已经有兴趣在这座岛国将其设立为一个专业。由于舞蹈治疗 (DMT) 在该国正处 于早期阶段, 我看到它可以发展的不同方向。作为一个舞蹈家、舞蹈教育家和研究者, 我看到了舞蹈和动作的重要性以及在疗愈方面的潜力。然而, 作为一门新兴学科, 我阐 明了舞蹈治疗 (DMT) 在斯里兰卡至少有三个方向可以发展——殖民化、民族化和去 殖民化。我的前提是, 鉴于舞蹈治疗 (DMT) 的历史和定位, 当它被引入到一个后 殖民地区时, 它就变成了殖民主义。正如我所论证的, 当舞蹈治疗 (DMT) 被引入到 像斯里兰卡这样的后殖民地区时, 它就强加了一个特殊的殖民框架。同时, 有些人试图 通过证明舞蹈治疗 (DMT) 早已存在于僧伽罗的传统仪式实践中, 在民族国家主义话 语中对舞蹈治疗 (DMT) 进行框定。本文聚焦斯里兰卡, 质疑了舞蹈治疗 (DMT) 中 殖民化和民族化的方法, 并提出发展一种去殖民化方法的可能性。

关键词: 去殖民主义, 舞蹈/动作治疗, 斯里兰卡, 殖民主义, 民族主义

Introduction

After receiving an undergraduate degree in fine arts from Sri Lanka, I was looking for ways to incorporate my passion for dance with academic studies in a new direction. I was attracted to dance therapy and was almost admitted into a graduate program in that discipline. Although I did not do my PhD in dance therapy, I had been exposed to various aspects of dance/movement therapy (DMT) and healing practices in the past. Between 2004 and 2020, I engaged in research projects on dance, performance, and therapy with various North American scholars. I invited some of them to Sri Lanka and collaborated with them, and I incorporated elements of the healing aspects of dance into the curriculum of the program where I currently teach. Through my experiences, I was exposed to the benefits of DMT, and, at the same time, was able to be more critical of the use of these practices in postcolonial sites such as Sri Lanka. Now in 2021, while seeing the benefits that dance therapy can offer to Sri Lankans, I also see the potential danger if it goes in some problematic directions.

Since DMT in the modern sense is relatively new to Sri Lanka, there are different directions that it can take. I demonstrate here three of these potential directions: colonial, nationalized, and decolonial. DMT becomes colonial, given its history and orientation, when it is introduced to a postcolonial site. However, an ethno-nationalist approach that tries to prove that such a thing existed in precolonial, traditional Sinhala rituals is also not helpful. In this article, I question both the colonial and the nationalized approaches in DMT in Sri Lanka and suggest that a decolonial approach is possible.

Currently, there is no single decolonial framework that can be universally agreed upon (and maybe there will never be). When I use the term decolonizing here, I am in agreement with the Puerto Rican thinker and scholar Ramon Grosfoguel. Like Grosfoguel, I use the term coloniality to mark the “colonial situations”—“the cultural, political, sexual, spiritual, epistemic and economic oppression/exploitation of subordinate racialized/ethnic groups by dominant racialized/ethnic groups with or without the existence of colonial administrations” (Grosfoguel, 2007, p. 220). DMT in Sri Lanka creates colonial situations. I agree with Grosfoguel when he articulates decolonization as “not an essentialist, fundamentalist, anti-European critique,” but a “perspective that is critical of both Eurocentric and Third World fundamentalisms, colonialism and nationalism” (Grosfoguel, 2007, p. 212). Decolonization involves addressing hierarchies of “racial, ethnic, sexual, gender, and economic relations” between the colonized and the Eurocentric knowledge structures (Grosfoguel, 2003, pp. 18–19). Therefore, the first step toward decolonization is to characterize the hierarchies and oppressive elements that stem from coloniality, even in postcolonial conditions. My critique of DMT does not end in coloniality. While critiquing the coloniality in DMT, I also question the attempts to nationalize it by glorifying the precolonial past.

Dance Movement Therapy

In ancient societies, various performance elements were used for healing through festivals, ceremonies and various rituals. Dance, movement, music, storytelling, and roleplaying have been used for healing purposes for many ages. However, it is only after the 20th century that those healing practices have been framed more professionally as “therapy” in the Global North. DMT is a relatively new discipline and is a profession developed mainly in the USA initially, in the period since the 1940s.

Two major professional organizations claim authority for DMT in the USA and the UK. In the USA, it is the American Dance Therapy Association (ADTA), and they characterize their practice as DMT. In their website, ADTA (n.d.) defines DMT as “the psychotherapeutic use of movement to promote emotional, social, cognitive, and physical integration of the individual, for the purpose of improving health and well-being” (American Dance Therapy Association [ADTA], n.d.). The Association for Dance Movement Psychotherapy UK (ADMP), which evolved from the Association for Dance Movement Therapy, claims the authority in the UK and uses the term “dance movement psychotherapy” (DMP). According to their website, ADMP (n.d.) defines dance movement psychotherapy as “a relational process in which client(s) and therapist engage creatively using body movement and dance, as well as verbal and non-verbal reflection” (The Association for Dance Movement Psychotherapy UK [ADMP], n.d.). Both these organizations define DMT as a psychotherapeutic tool and have also established it as a profession.

Dance and Movement Therapy in Sri Lanka

The use of creative arts in a professional therapeutic manner is relatively new to Sri Lanka. As drama therapist Tehani Chitty asserts, although traditional healing ritual practice existed in Sri Lanka, “it has now been formulated by the Western strain of psychology as well, which allows us to use it more explicitly as a form of therapy” (Dawoodbhoy, 2019). Among other creative art therapies, DMT is the newest for Sri Lanka, and individuals have begun to use it in a very loose manner over the last 15 years. This includes the work that Venuri Perera, I, and others have been doing, separately, in using dance for individual and community well-being. For example, in 2009, when I was working with former child soldiers of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), I used dance in workshops that promoted national integration. We were not doing this kind of work in a therapeutic framework, yet there is currently an interest among individuals in Sri Lanka (both foreign and local) in developing DMT as a profession and to have a licensing system as in the USA.

Since Sri Lanka has a rich tradition of performing arts, therapists and researchers working with creative art therapies turn to traditional dance and rituals. Most of them are attracted to the low country dance tradition (or Ruhunu dance), which is primarily practiced in the western and southern parts of the island. Yet this move to working with low country dance traditions has a colonial legacy. Colonial writers have characterized this low country tradition as a ritual dance tradition dealing with demons, devils, and spirits. The colonial discourse of black magic, shamanism and exorcism has schematized this tradition as a devil or demon dance tradition, and later researchers have also characterized these ritual dances as devil or demon dance practices. This discourse of devils, demons, and exorcism has helped drama and dance therapists to find their tools and to articulate them into therapeutic practices. The therapists are not, however, attracted to Kandyan dance, the most popular dance tradition in Sri Lanka. Kandyan dance has been elevated as the national dance, and it is used for the national pride of the Sinhala, the majority ethnic group in the country. Its repertoires are generally refined and difficult to tweak for therapeutic purposes because of cultural and political reasons. The therapists do not seem to be attracted to the Tamil dance traditions in the country, and since I am more familiar with the dance traditions of the Sinhala people in Sri Lanka, I am focusing only on those in this article.

FIGURE 1 | The author performing in the ‘Masks and Myths: Devils and Dancers from Sri Lanka’ event at the Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts, Chicago, October 2018, photos by Tom Rossiter.

Coloniality in Dance Movement Therapy

When DMT is introduced to a postcolonial site, it carries colonial baggage with it. The history of the discipline of DMT in both the USA and the UK has been influenced by Laban Movement Analysis (LMA), a highly structured movement analysis system developed by the Austro-Hungarian dance theorist Rudolf von Laban. Laban and his followers used LMA to characterize and understand human behaviors. I see the value of LMA as an attempt to analyze dance and human movements in general. However, an epistemic question arises when people use LMA to analyze the dance and movements of colonized cultures. As Grosfoguel claims, “the hegemonic Eurocentric paradigms that have informed western philosophy and sciences in the ‘modern/colonial capitalist/patriarchal world-system’ for the last 500 hundred [sic] years assume a universalistic, neutral, objective point of view” (Grosfoguel, 2007, p. 213). Therefore, dance movement therapists cannot understand or try to provide solutions to postcolonial sites using systems of structured movement analysis that have been developed based on the realities of the Global North. Some of the tools and knowledge used in DMT are derived from Europe and the USA, and it is extremely limiting when there are attempts to apply them cross-culturally; there is a failure to grasp the nuances of the postcolonial cultures.

Global political and economic structures reinforce colonial relationships when they are introduced to postcolonial sites. Scholars have characterized how global governance operates by commodifying trauma, affect, and emotion in the form of therapy (Husanović, 2015; Pupavac, 2005). The global governance is the framework in which the Global North plays the dominant role, promotes rights, and sometimes offers therapy to achieve its goals. As Pupavac (2005), a scholar on international relations, asserts, global governance reconfigures rights as external interventions “on behalf of infantilised citizens to avert psychosocial dysfunction and support them in becoming good citizens” (pp. 46–47). According to her, these therapeutic interventions are “informed by Anglo-American social psychology” (Pupavac, 2005, p. 56). This is a colonial approach, both at the epistemic and the practical levels. Thus, dance movement therapists, and various other creative arts therapy projects in Sri Lanka, approach their work through an Anglo-Eurocentric colonial framework: to assist the infantilized citizens in becoming good citizens.

The colonial power structure is re-established through the therapist–client dichotomy in DMT. In the USA or the UK, the relationship between therapist and client is straightforward and no hierarchy is maintained. However, when this dichotomy is introduced to a postcolonial site, such as Sri Lanka, it is charged with a colonial relationship and the relationship is no longer neutral. Some Euro-American therapists might genuinely want to take the side of the oppressed; however, as Grosfoguel reminds us, “the fact that one is socially located in the oppressed side of power relations, does not automatically mean that he/she is epistemically thinking from a subaltern epistemic location” (2007, p. 213). Therefore, in a postcolonial site, the relationship between therapist and client becomes hierarchical along the lines of expert versus incompetent, empowered versus disempowered, privileged versus underprivileged, authority versus powerless, superior versus subordinate, white versus brown/black and enunciate versus voiceless. In these contexts, the therapist, the expert (who are mostly white), becomes the voice, appears benevolent and sometimes hijacks the situation, leading to the local communities being more dependent on them. Because of this colonial relationship, Sri Lankan therapists require a form of “baptism” from the organizations in the USA or UK in order to be called professional therapists. I agree that having a license can be helpful in maintaining professionalism; yet, when it comes through the USA or UK, it can also create colonial relationships.

FIGURE 2 | Kolam, in Mirissa, Sri Lanka, photos by Sewwandi Daladawattha, courtesy of the AFCP project, University of Peradeniya.

Dance Education, Nationalism, Employability, and Therapy

Sri Lankans have been practicing various healing rituals for centuries, and among these, the practice of ritual dance still functions as a living tradition in the country. After independence from the UK, ritual and traditional dance did receive attention and was taught in Sri Lanka as a form of Sinhala national heritage. Since the 1950s, ritual dances have been ubiquitous in the dance curricula at both secondary school and university levels. As anthropologist Susan Reed (2010) convincingly demonstrates, dance, particularly Kandyan dance, was elevated into a national dance of Sri Lanka by the ruling elites after the 1950s. These elevated traditional dance forms received renewed interest when they were introduced into public school and degree level curricula in the same decade. Since the pioneers who developed this were Sinhala nationalists, the curriculum included rituals that were only practiced by the Sinhala people. Reed (2010) characterized this as a “ritual-based curriculum” (p. 150). Even though dance as a discipline has various possibilities and capacities, since the 1950s, it has been restricted in Sri Lanka to the teaching and learning of the ritual dance sequences of the Sinhala people.

FIGURE 3 | The author performing in the ‘Masks and Myths: Devils and Dancers from Sri Lanka’ event at the Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts, Chicago, October 2018, photos by Tom Rossiter.

Recently, however, with the emergence of the discourse on humanities education and relevance and employability, dance education has been highlighted. The ritual-based curricula of universities have produced graduates who have become dance teachers with ritual dance knowledge. However, since recent governments have focused on STEM education and employability, ritual dance is beginning to lose its currency in the public education system. Even if the countries that introduced the concept of STEM education are abandoning it, the Sri Lankan government, unfortunately, has only started to implement it recently. Currently, career opportunities are extremely limited for dance graduates in Sri Lanka. Preserving the tradition and showcasing national heritage are no longer enough to justify the importance of teaching and learning dance in public schools and universities. Dance curriculum developers, educators, and university lecturers are now looking for ways to justify the importance of dance education in the country and the employability of dance graduates. In this context, dance therapy has become a buzzword in public schools, in universities, in the Ministry of Education, and in the National Institute of Education.

Amid the pressure for dance education to produce employable graduates, it seems that DMT does attract the attention of the public school curriculum in Sri Lanka. However, given the ethno-nationalist history of dance education in public schools and its existing ritual-based curriculum, this could easily become a nationalizing approach. In this nationalizing DMT, traditionalist rhetoric would sound like “in our country, we practiced dance therapy for thousands of years before the Westerners,” and similar statements in the field of dance education can already be heard. It is noticeable that some contributors to the ritual-based curriculum have begun to focus on the therapeutic aspects of Sri Lankan ritual dance. Although nationalists try to argue that Sri Lankans had been practicing dance therapy for ages, the irony is that they had to be “baptized” by Euro-American organizations in order to seek their licenses.

On another front, some foreign and local researchers and practitioners draw parallels between Sri Lankan traditional dance rituals and the DMT used in Euro-American contexts. However, Waidyawathie Rajapaksa, a scholar of traditional dance, has a different view on this. The daughter of the famous Kandyan traditional dancer and drummer Amunugama Suramba, Rajapaksa embodies her family’s centuries-old knowledge of dance. According to her, what happens in dance rituals and in Western “psychotherapy” or “therapy” is very different (W. Rajapaksa, personal communication, December 8, 2020). She highlights in particular the difference between the roles of the people involved in dance rituals and in DMT. The relationship between the ritual priest and the receiver of the healing (āturayā) is very different to the relationship between the therapist and the client/patient in DMT (W. Rajapaksa, personal communication, December 8, 2020). In dance rituals, āturayā, the receiver of the healing, is sometimes considered a patient. However, occasionally, he/she is the sponsor of the ritual and not considered a patient in the western sense.

Given the history of the country, which includes 26 years of civil war (1983–2009), ethnic nationalism has evolved into a monster in Sri Lanka. There is a great deal of mistrust among Sinhala, Tamil, and Muslim communities. At the same time, there are efforts in various pockets of artists, scholars, and activists who are attempting to collaborate among ethnic groups while also trying to heal themselves. Therefore, a nationalized DMT approach would not help, as it can easily slip into ethno-nationalism, where the Sinhala majoritarian sentiment becomes the superior and dominant voice. This can reproduce hierarchies and oppressive systems as problematic as the colonial approach.

Decolonial Approach to Dance Movement Therapy

Is a decolonial approach to dance movement therapy possible? Yes, I think so. I am not against DMT. There are moments when people need various kinds of healing. I am a dancer and a choreographer who works with my own body and with other bodies. Therefore, I know dance can heal individuals and communities; I have witnessed the power of the healing aspect of dance in various contexts. However, in Sri Lanka, I see the danger of either the colonizing or nationalizing of DMT in the near future. Dance cannot heal individuals or communities in postcolonial sites when it establishes colonial relationships. Therefore, we do not need colonial DMT or DMP. A fabricated nationalized DMT approach would also not be helpful. If there is an awareness of these two traps, dance and movement can be used for healing purposes in a more holistic, inclusive and non-hierarchical manner. This, I suggest, is what could be a decolonial approach to dance and movement as a healing practice. It is only this kind of approach that can facilitate some healing to postcolonial sites through dance and movement.

Terms such as DMT or therapy also need to be rethought. Instead of therapy, a decolonial approach should articulate it as a collective healing practice. A decolonial dance movement healing practice should challenge the patriarchal epistemic systems, the experts speaking for the so-called voiceless, and the dichotomies such as expert–incompetent, therapist–client. Rather than structured movement analysis, the understanding should come through bodies and embodied experiences and local realities, and it should incorporate, where possible, indigenous knowledge systems.

A colonial or nationalized approach to DMT cannot address the real issues of postcolonial societies. While colonial DMT maintains a Euro-American superiority, a nationalized DMT can antagonize individuals and communities, as it can be changed along ethnic lines. Both of these approaches may sit with the oppressed and soothe them. However, these approaches cannot address or even discuss the root causes of social issues such as poverty, hierarchy, privilege, injustice, discrimination, and ethnic violence.

A decolonial approach to DMT should address the issues at an individual/personal level and connect them to structural issues and systemic oppressions. It should, of course, support individuals in dealing with their issues. However, we cannot ignore that most of those issues stem from oppressive systems. While supporting individuals to gain their personal peace, this approach should eventually lead to a more just society. Personal healing should lead to solidarity in the community and among communities.

Acknowledgment

‘Decolonising Dance Movement Therapy: A Healing Practice Stuck between Coloniality and Nationalism in Sri Lanka’ by Sudesh Mantillake was first published in the Third Text online journal in October 2021, the Third Text online journal is published by Third Text Ltd, and is a companion to their print journal, Third Text, which is published by Routledge, Taylor & Francis.

About the Author

Sudesh Mantillake is a dancer, choreographer, researcher, and educator. He received his BA degree from the University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka; his MSc from the University of Lugano, Switzerland; and his PhD from the University of Maryland, USA. He is trained in Kandyan dance of Sri Lanka and Kathak dance of India, theatrical clowning, and contemporary dance. His recent creative works include My Devil Dance, Masks and Myths, and In Search of Ravana. Sudesh is a permanent faculty member of the Department of Fine Arts at the University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka.

References

ADMP. (n.d.). What is dance movement psychotherapy? Association for Dance Movement Psychotherapy. Retrieved June 21, 2021, from https://admp.org.uk/what-is-dance-movement-psychotherapy/

ADTA. (n.d.). What is dance/movement therapy? Retrieved June 21, 2021, from https://adta.memberclicks.net/what-is-dancemovement-therapy

Dawoodbhoy, Z. (2019, September 18). Performing the pain away: An alternative form of therapy in Sri Lanka. Roar Media. Retrieved July 01, 2021, from https://roar.media/english/life/in-the-know/performing-the-pain-away-an-alternative-form-of-therapy-in-sri-lanka

Grosfoguel, R. (2003). Colonial subjects: Puerto Ricans in a global perspective. University of California Press.

Grosfoguel, R. (2007). The epistemic decolonial turn. Cultural Studies, 21(2–3), 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162514

Husanović, J. (2015). Economies of affect and traumatic knowledge: Lessons on violence, witnessing and resistance in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Ethnicity Studies/Etniskumo Studijos, 2, 19–34.

Pupavac, V. (2005). The demoralized subject of global civil society. In G. Baker & D. Chandler (Eds.), Global civil society: Contested futures (pp. 45–58). Routledge.

Reed, S. A. (2010). Dance and the nation: Performance, ritual, and politics in Sri Lanka. University of Wisconsin Press.