Lingbi stone, Kemin Hu Collection.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2021) 7(1):10–25 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2021/7/1 |

Interpreting the Natural: Contemporary Visions of Scholars’ Rocks

Reflections on curating the exhibition: Interpreting the Natural: Contemporary Visions of Scholars’ Rocks, October 21st–Nov 30th, Gallery Korea, Korean Cultural Center, New York, NY, USA

诠释自然: 文房供石的当代视野

诠释自然: 文房供石的当代视野

10月21日至11月30日, 纽约韩国文化中心韩国馆

Brandeis University, USA

Abstract

This article uses the concept of the scholar’s rock tradition from East Asia as a framework for the author’s curatorial project at Gallery Korea, Korean Cultural Center, New York. The contemporary art exhibition is discussed in relation to the traditional aesthetic. Universal connections between art and nature are included. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, the author developed a series of online events to address the main themes of the show with the artists in conversation with museum curators, art historians, and private collectors.

Keywords: scholars’ rocks, suseok, suiseki, gongshi, Taihu rock, Lingbi stone, Richard Rosenblum, Kemin Hu

摘要

本文以东亚赏石传统概念作为作者在纽约韩国文化中心韩国馆的策展项目框架。当代艺术展讨论的是传统美学以及艺术与大自然之间的联结。由于COVID-19所限, 作者开展了一系列的线上主题活动, 对话交流的艺术家有博物馆馆长、艺术史学家和个人收藏家。

关键词: 赏石, 供石, 太湖岩, 灵璧石, Richard Rosenblum, 胡可敏

Introduction

The process of curating this exhibition began over three years ago, but my journey with scholars’ rocks or viewing stones began long before that. A scholar’s rock is a naturally shaped stone traditionally valued in East Asia as an object of contemplation (Hu, 2002). When I visited China in 2015, I discovered these rocks in nearly every interior space, from hotel lobbies to political offices to private homes and gardens. Oftentimes the stones were covered with dust, or languished in a corner behind the bric-a-brac of everyday life. If outside, they were often planted in the dirt without a stand. They seemed to be everywhere. As I was assembling this show, I visited contemporary art galleries that specialize in Chinese artists and masterworks, where my curiosity was often met with skepticism about this topic. From their perspective, they consider these rocks a form of low art. A non-profit art gallery in New York City, where I proposed this show, could not understand the concept or its relevance to contemporary art. In 2019, the movie Parasite, directed by Bong Joon-Ho, that prominently featured a scholar’s rock, changed everything (Willis, 2020). The movie won four Academy Awards, becoming the first non-English language film to win for Best Picture, and the first South Korean film to be nominated. Suddenly, we had a cultural reference point for this show. Not long after came the opportunity to exhibit this show at the Korean Cultural Center in New York, NY.

Scholars’ Rocks: Traditions of China, Korea, and Japan

Rock collecting is a universal human pastime. Throughout East Asia, scholars have cultivated distinct traditions: in Korea, suseok (Chernick, 2020); in Japan, suiseki (Benz, 2001); in China, gongshi (Hu, 1998). The most prized “kernels of energy and bones of the earth” (Hay, 1985) were created by water or wind carving away the geological structure until only the essence of the rock is left behind. The stones became appreciated as an art form when they were enhanced by artisans, set into elaborately carved wooden bases or trays of sand and water, and brought indoors for contemplation. Daoist practitioners understood these unique stones as an index or a synecdoche of harmony with nature. As the stones were passed from generation to generation, they signified an authentic connection to the landscape and an aesthetic reminder of that spiritual connection.

Lingbi stone, Kemin Hu Collection.

An appreciation of these stones represents cultural value for Korean, Chinese, and Japanese collectors. With new affluence came increased demand for such ancestral heritage. Merchants would often find or carve natural stones and sell them in the marketplace. Commercial availability enhanced their popularity. With the rise of new wealth in Korea and China in the past 50 years, these naturally occurring and worked scholars’ rocks have become more sought after. They signify a connection to the ancient past, and collectors acquire them to express prosperity and hope for the future.

Richard Rosenblum, an American sculptor and a collector of scholars’ rocks, made the most significant contribution to a global fascination with this tradition by researching these stones and bringing them to a Western audience in the late 1990s (Fineman, 1996). His public exhibitions resulted in gifts to the permanent collections of the Harvard University Art Museum, the Museum of Fine Art Boston, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and other museums (Mowry & Rosenblum, 1996). By situating these rocks in conversation with civilization’s cultural treasures, he elevated their status in the West (Rosenblum, 2001). The scholars’ rocks in his collection had a profound influence on his own work, transforming his classical figures into expressive gestures (Berliner, 2020).

Today, scholars’ rocks continue to resonate with viewers. The surge of interest in scholars’ rocks or viewing stones in the art world, and in pop culture due to the movie Parasite, comes at a time when things feel out of balance with nature, the environment, and society. The artists in this show are all responding to this moment. A reverence for rocks and nature is needed now, more than ever.

Korean chrysanthemum flower stone, Thomas Elias and Hiromi Nakaoji Collection.

As a sculptor, the scholars’ rocks’ appeal is in their visual three-dimensionality. One often reads about the aesthetics of the stones, that the best ones are asymmetrical, with wrinkled surfaces, perforated with holes, resonant when struck, and suggestive of landscapes (Mowry, 2015). I see them as a form of abstract sculpture. They embody the original impulse to elevate a found object to fine art status, not unlike a “readymade,” where a commonplace artifact is viewed as art. The odd shapes invite reflection and contemplation. The viewer can see whatever is in the mind’s eye—in that sense they are akin to Rorschach ink blots that are used to elicit psychological projections from a viewer’s imaginative responses (Smith, 1996). Everyone can relate to finding a beautiful stone, picking it up, and setting it on the desk or windowsill. Recent fads such as “pet rocks,” or the idea that the stone is looking back at the viewer, reinforce the ubiquity and chimeric qualities of viewing stones. Rocks are timeless, and universally appealing.

Taihu rock, Kemin Hu Collection.

The inspiration for me as an artist curator of this Korean Cultural Center exhibit was Takashi Murakami’s Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture exhibition in 2005 at the Japan Society in New York, NY. Murakami’s exhibition blurred the lines between high and low art and culture, and in doing so created a much wider audience for Japanese contemporary art. By understanding the popular forms of art and culture, such as manga, which are comic books or graphic novels, as extensions of traditional forms of ukiyo-e or Japanese woodblock prints, the show brought a serious focus to the global phenomenon of anime, or animated movies, and made the imagery more accessible. Little Boy opened a window into post–World War II Japan including the societal impact of surviving the atomic bombs and its slippage on the global stage (Murakami, 2005). In these times of humanity’s assault on nature, the idea of turning to contemporary artists to connect our interpretations of the living nature of stones made sense. This was the inspiration for my show.

My first encounter with the idea of viewing stones was the fabulous taihu rock in the front lawn of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. I became more intrigued when I saw Liu Dan’s work in the MFA’s Fresh Ink show in 2010 (Sheng, 2010). Liu painted 10 portraits of a scholar’s rock (Loong & Yee, 2019). I was intrigued and I wanted to know more. My husband, Andy Moerlein, a sculptor and educator, has been studying these rocks for many years, thus he is drawn to contemporary artists working within this philosophy and aesthetic. Once we started doing studio visits and talking to artists, who referred us to other artists, we started seeing scholars’ rocks all around us in nature.

When I started researching scholars’ rocks, I immediately came across Kemin Hu’s books in my local library. Hu’s father was a third-generation stone collector. Kemin continued this tradition in America, becoming a scholar, author, and public speaker who champions the aesthetics of stone to Western audiences. As I looked further, I found a video of Hu during an exhibition of her stones at the Public Library in Weston, MA, in 2001, Sculpture by Nature: Chinese Scholars’ Stones Exhibition from the Collection of Kemin Hu (Gallery talk, 2001). I went to visit her and see her collection several times in Newton, MA, and she generously loaned two of her stones to this show. When asked if the stones have spirit, she will say that people who see something in the stones have spirit (Hu & Elias, 2013).

Contemporary Visions: The Korean Cultural Center Exhibit

My goal in curating this show was to bring contemporary artists from different cultural backgrounds, such as German, Italian, Argentinian, Chinese, and Korean, into a conversation with the ancient practice of stone appreciation. Since scholars’ rocks are a form of sculpture, I chose mostly sculptors. Each contemporary artist selected for this exhibition presents work that responds to the traditions of Chinese gongshi, Korean suseok, or Japanese suiseki.

The Korean Cultural Center in New York selected my curatorial proposal, Interpreting the Natural: Contemporary Visions of Scholars’ Rocks, as the winner of its annual “Call for Artists 2020.” This group exhibition features recent artwork by 10 contemporary artists in dialogue with authentic viewing stones from the Thomas Elias and Hiromi Nakaoji collection and the collection of Kemin Hu. The exhibit offers contemporary art inspired by the traditional scholars’ rocks and encourages reflection on our enduring relationship with nature. As we confront the current pandemic and witness the climate transformation evident around us, artists who respond to the ancient reverence of stones provide pertinent ideas for finding solace or optimism during our global imbalance.

Due to Covid-19restrictions, I created a five-part online series featuring artists in this show in conversation with curators, art historians, and collectors. My ambition was to amplify the work of each artist and connect the history, research, and scholarship on viewing stones to contemporary art practice. Each talk focused on one of the five main themes of this exhibition: the human–nature connection, the microcosm–macrocosm relationship, the rocks as a portal into another world, collecting and appreciating viewing stones, and the relationship between abstraction and representation.

Taihu rock, Timothy Springer Collection.

The first conversation, “Expressionism and Abstraction: from Scholars’ Rocks to Contemporary Art,” featured Nancy Berliner, Wu Tung Senior Curator of Chinese Art, Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, MA (see her recent “Art for this Moment” blog post about scholars’ rocks); Dr. Timothy Springer, scientist, entrepreneur, and rock collector; and two artists in the show: Mark Cooper and Laura Moriarty. Dr. Springer has a private collection of monumental garden stones in Newton, MA. He was inspired to collect after seeing a scholar’s rock the size of a house in a Ming Dynasty painting. He traveled to China to select this stone, shipped it to the USA, and installed it with the professional advice of his teacher, Kemin Hu. Tim discussed how rocks are carved by water, almost like a mortar and pestle, until the point where the metamorphic patterns are revealed. As Dr. Berliner so eloquently stated when asked how she feels about embellishments made on natural stones by artisans, “there is nothing as natural as the act of creation or the shaping of an object in the hand of an artist.”.

The impulse to be in conversation with the geological process is what led Laura Moriarty to transform her wax paintings from two to three dimensions. Not unlike the mechanisms of the tectonic plates, Laura heats wax, pours the liquid into molds, lets it cool, and then breaks them apart, building layers upon layers until she has produced evocative wax stones with the quality of minerals, aggregations, or geodes. Then she melts one face of these sculptures and drags it across long paper scrolls to create mesmerizing stripes that evoke layers of sediment marking eons of geological time. Likewise, a similar process is what drives the creation of Mark Cooper’s elaborately fabricated, expressively painted, “anything goes” type of constructions that evoke the display of a rock upon a base. Using unexpected materials such as ceramic tiles, plywood, photography, oil on canvas, resin, and c-clamps, he takes a maximalist approach to this minimalist tradition and the result is greater than the sum of its parts. Teetering between two and three dimensions, the works stare out at the viewer and mirror the viewer in turn.

Laura Moriarty, Tableau, 2018/2019.

Pigmented beeswax, black sand, metallic pigment, powder charcoal.

The second conversation, “Portals: Collecting and Interpreting Evocative Rocks,” featured Dr. Thomas Elias, chairman of the Viewing Stone Association of North America, who loaned one of his Korean chrysanthemum stones to the show; Dr. Virginia Moon, Associate Curator of Korean Art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and two artists in the show: Andy Moerlein and Elisa Pritzker. Dr. Elias collects traditional viewing stones from Japan, China, and Korea and he publishes on the aesthetics of this living practice (Elias, 2014). In his new book, Contemporary Viewing Stone Display (Elias, Turner, & Harris, 2020), he presents the development of a North American aesthetic based on the unique stones of the USA that goes beyond the mimicking of East Asian traditions. Andy Moerlein grew up in Alaska, and has a deep appreciation and love for the mountains in his home state. In his highly manipulated woodcarvings, he explores the intersection of accident, intervention, and the natural grain patterns as he tells the stories of iconic mountains and landscapes.

The ceremony of finding stones wherever she travels and bringing them back to her studio where she works her magic upon them is unique to Elisa Pritzker. Inspired by the indigenous patterns of the Selk’nam people of Patagonia, she invents her own iconography of symbols and marks that she paints onto the face of her rocks in the ritual of her studio practice. The installations that she creates with her artworks invite the viewer to meditate upon the living nature of stones and their connection to humankind.

Mark Cooper, Stone Soup IV, (front and back) 2020, ceramic, wood, paint, photographs, ink on paper, and C-clamps.

Andy Moerlein, Uncharted, 2017 red oak, plywood, beech, maple.

Elisa Pritzker, Tiny Magic Stones, 2020, acrylic paints, stones from Oaxaca-Pacific Ocean.

Dr. Virginia Moon noted how the variety of interpretations in the current show contrast to the more rigid and consistent aesthetics witnessed in China, Japan, and Korea centuries ago. To her, this is a natural development and a reflection of the different cultures represented by contemporary artists today where individuality is more emphasized and prized in the role of the artist. More predominantly in the USA and the West in general, individualism has been often celebrated, and self-expression tends to be the norm. Culturally in China, Korea, and Japan, the interpretation of the viewing stone is more collectively agreed upon, stable, and understood within certain parameters of the rich lineage of this aesthetic tradition. For me, the artists in this show bring a revitalized appreciation of the spiritual quality of the stones and, by extension, nature.

The third conversation, “Nature’s Representation, Interpretation and Enculturation in Viewing Stones,” featured Dr. Kevin Greenwood, Joan L. Danforth Curator of Asian Art at the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College (see a video essay featuring Dr. Greenwood on Chinese Scholars’ Rocks (Greenwood & Lakos, 2017)); Dr. Yao Wu, Jane Chace Carroll Curator of Asian Art at the Smith College Museum of Art; and two artists in this show, Laura Cannamela and JooLee Kang. Dr. Greenwood touched upon the cosmology of East Asian art and the concepts of yin and yang or harmony, resonance, and the way the microcosm reveals the macrocosm. He discussed the inseparable link between rocks and mountains evident in East Asian stone appreciation and philosophy. Ms. Wu followed up on that by situating the reverence for rocks and their cosmological symbolism beyond artistic traditions. She noted the significance of rock or stone in two of the Four Great Classic Novels in Chinese literature—Journey to the West and Dream of the Red Chamber (alternatively titled The Story of the Stone)—where the main characters are literally born from an incarnation of stones. She further observed that like the 2019 Korean film Parasite, Chinese TV adaptations of the two novels in the 1980s popularized the imagery and notion of stones as an embodiment of supernatural powers.

Laura Cannamela, Cleofan, 2019. Stoneware, wood fired.

Viewing stones have emerged in contemporary artwork as a representation and symbol of nature and the human connection to the environment. Laura Cannamela’s ceramic sculptures explore the relationship of time, rock, and water using the interplay of color and form to focus the viewer on her intimate scale. The way that she works to manipulate the clay and then fires them allows nature, in the form of smoke and ash, to shape her work, which is parallel to the way the stones are shaped by nature and enhanced by the work of artisans. JooLee Kang’s ballpoint pen drawings create three-dimensional effects using her cross-hatching technique to bring to life the visions she breathes into the viewing stones, melding insects, animals, and plants in a collaged-type image. Kang’s encapsulated worlds reveal her relativist linking of the large within the small. Her work comments upon humanity’s impulse to tame nature and coexist with it. Kang believes suseok demonstrate our desire to have nature nearby and they provoke us to imagine things in the rocks. For her, they represent the close bond between humans and nature and the ways that all living things are woven together into the whole.

JooLee Kang, Viewing Stone #1, 2020, ballpoint pen on paper.

The fourth conversation, “Strange Bedfellows: How Found objects, Mineralogy and Ancient Viewing Stones Deliver a Relevant Message,” featured Dr. Kyunghee Pyun, art historian and faculty at the Fashion Institute of Technology (see her recent interview about the suseok in Parasite in Artnet (Chernick, 2020)); Dr. Aida Yuen Wong, art historian and faculty at Brandeis University; and two artists in the show: Furen Dai and Woomin Kim.

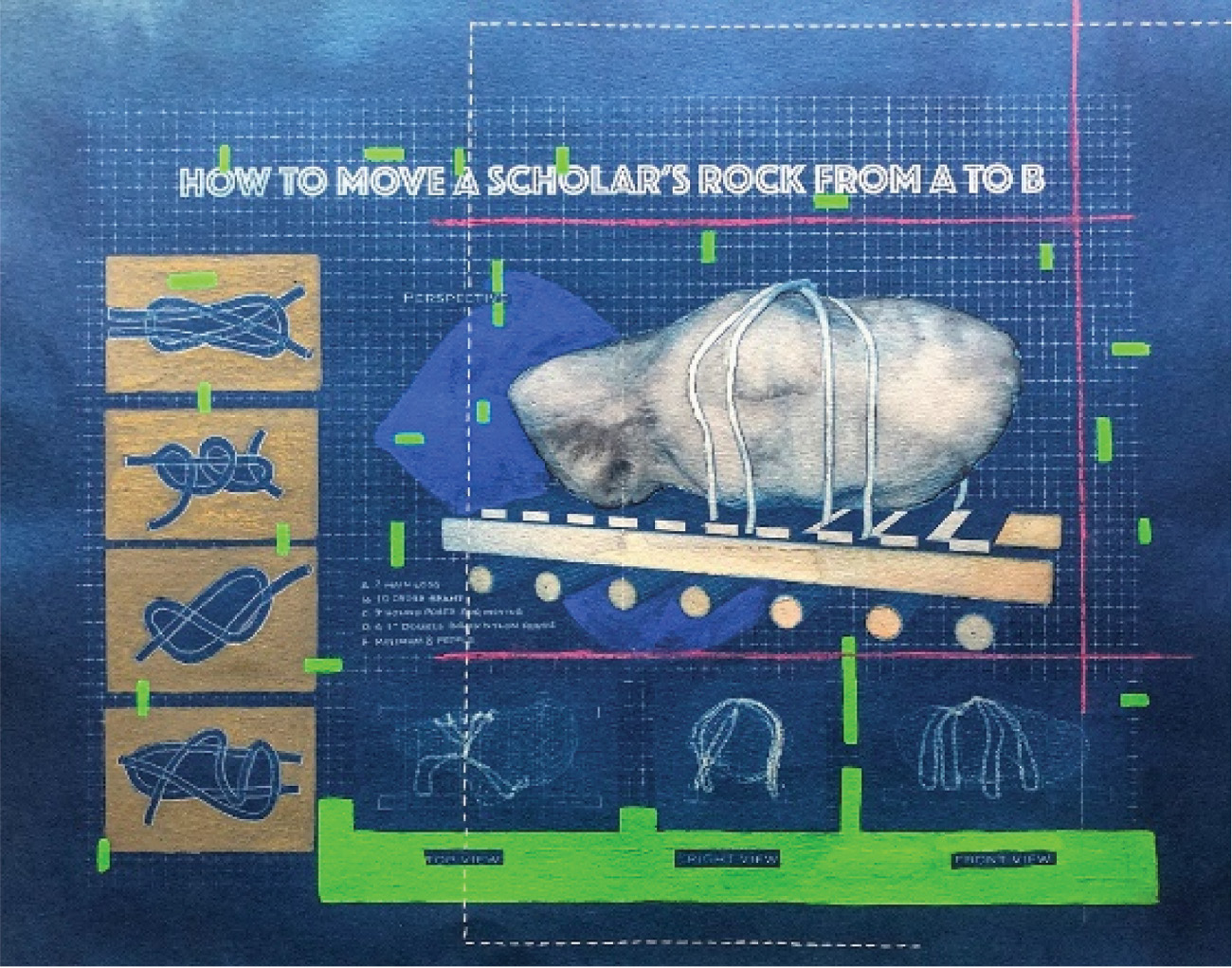

Dr. Wong made the connection between Japanese gardens and suiseki or scholars’ rocks and their influence on the concept of feng shui and interior design. From a metaphysical perspective, rocks are believed to be able to collect and condense positive energy to promote harmony, security, and good health (Covello & Yoshimura, 2009). Furen Dai’s drawings resemble architectural blueprints. They explore the conceptual history of the commodification of the large garden stones when removed from nature and transported. Using humor, she focuses on the unseen labor required to move the stones as a metaphor for the labor in the artist’s studio. Woomin Kim uses textiles and mixed media sculptures to illustrate natural mineralogical structures and interrogate the geological integrity of contemporary life. Using silicon fingernails and kitty litter, for example, Kim makes connections between the structure of minerals and their industrial use. Her embroideries flatten out the rocks and evoke chaekgeori, a traditional form of Korean still life painting that uses a flattened perspective to convey three-dimensional effects.

Dr. Pyun focused on the living practice of collecting stones in Korea and the pilgrimage, journey, and cultivation of self that they symbolize. She emphasized that in this moment of a global pandemic, climate change, political divisiveness, and social injustice, one might say nature is revolting to human’s lack of respect for her. She believes that there is a natural balance and things are wildly out of balance—swinging out of control on a pendulum.

Furen Dai, How to Move a Scholar’s Rock from A to B (Proposed Plan 5-A), 2020, Drawings: colored pencil, cyanotype, gouache, vinyl (thumbnail).

Woomin Kim, Minerals in Use, 2018, mixed media.

The fifth and final conversation, “Presentation, Arrangement and Display—Where Scholars’ Rocks and Contemporary Curatorial Trends Converge,” featured Jan Stuart, Melvin R. Seiden Curator of Chinese Art, National Museum of Asian Art (see her recent online lecture “Rocks as Art—A Chinese Tradition” (Stuart, 2020)); Craig Yee, Founder of Ink Studio in Beijing; and two artists in the show: Susan Meyer and Christopher Frost. Jan Stuart began her remarks by introducing the recent curatorial trends of placing something modern in dialogue with something traditional. Stuart thinks the artifacts silenced in the passage of time, such as scholars’ rocks, remind us in the current age of increasingly technological contemporary trends that we can learn from nature.

Christopher Frost, Floating Bridge Century Sonny, 2016, wood, paint, cast concrete.

Movement defines Chris Frost’s approach to making cast concrete sculptures in response to the traditional rocks’ form, material, and conceptual relationship of the rock to nature. Frost invites the viewer to see his sculpture in the framework of an East/West, contemporary/ancient, natural/industrial dialogue that his sculptures imply. Susan Meyer’s use of scale and unexpected materials defines the unique aesthetic of her mixed media sculptures. The brightly colored acrylic structures draw the viewer’s attention to the base that supports her fabricated rock forms. However, the base itself evokes the feeling of a geometric scholar’s rock, thus sublimating the relationship between the rock and its display. Craig Yee made the connection between the role of the curator and the function of the base for the rocks—both of which create context and meaning. He emphasized the opportunity of the historical context that allows the contemporary work in this show to achieve its fullest potential. He added, “From a Euro-Anglo perspective, we see the rock as a static object, but from an East-Asian perspective artists and collectors saw the rock as dynamic and transformational. Viewing a rock, or art, was a process for transforming the self (in both the artist and the viewer).”.

Susan Meyer, Plinth, 2019, wood, acrylic, collage, paint, foam, plaster, wire, and paint.

In Conclusion

As a result of the exhibition and the accompanying online conversation series, curators, artists, art historians, and collectors have come together to create a community of voices by sharing a deep fascination and appreciation with the aesthetic of suseok, suiseki, and gongshi. These rocks reveal some essential connections and shared beliefs that serve as an antidote to the isolation of these socially distant times. In that sense, they are the cosmic force that brought everyone together and forged new connections.

When I shared these insights with Dr. Kyunghee Pyun, she suggested that the whole process of preparing for the show during Covid-19 could be viewed as a collaborative research process. According to Pyun’s observation, curators, scholars, art critics, and artists have summarized their foundations and assumptions as well as the creative process itself and presented their ideas in a series of conversations among themselves and with audiences in the five public programs and over a dozen one-one-one interviews I conducted with artists and art historians. “The process is transformative in a sense that artists gained confidence, justification, or theoretical corrections for their works. Art historians also had a moment to reflect on the contemporary legacy of a centuries-old literati predilection of Confucian scholars of East Asia, successfully carried out by artists around the world. The group who exchanged views during this exhibition then re-calibrated future projects and epidemiological principles” (K. Pyun, personal communication, November 29, 2020).

I created the online conversation series to replace the types of informal conversation that the artists would normally be having at in-person gatherings, and to give the artwork a wider reach using Zoom technology. Since there were very few visitors to the exhibition, the artworks and the artists connected with audiences in the virtual world. The panelists brought the exhibit into dialogue with important cultural and visual references from East Asia. Our conversations contrasted classical and contemporary practices, revealing the context and intentions of the artists. I learned that scholars’ rocks are hard to explain but easy to understand. The same can be said for contemporary art. The rocks acted as a code breaker of sorts that allowed deeper insights into the artwork in this exhibition.

In that spirit, I have brought the artists in this show together to bring the focus back to nature, to remind us of our interdependence with nature and to search for our better selves through rocks. The scholars’ rocks evoke our connection to nature and, in turn, a connection to our inner selves. If we think of the interrelationships in our world today, we are reminded of climate change, COVID-19, and a deeply divided country. This show brings the past, as represented by the rocks, into a dialogue with the present, as represented by the artworks, and invites all of us to redefine the future.

About the Author

Donna Dodson is a visual artist, Visiting Scholar at Brandeis University, freelance journalist and independent curator. Her research interests include the Amazons, from ancient art including women warriors around the globe, and pop culture including Wonder Woman. Email: donnadodsonartist@gmail.com

References

Benz, W. (2001). Suiseki: The Asian art of beautiful stones. New York, NY: Sterling.

Berliner, N., (2020, September 28). Taihu rock. Retrieved December 03, 2020, from https://www.mfa.org/article/2020/taihu-rock

Chernick, K. (2020, February 07). A highly collectible rock plays a key role in the Oscar-nominated film ’Parasite.’ Here’s the actual meaning behind it. Retrieved December 03, 2020, from https://news.artnet.com/art-world/guide-suseok-stone-parasite-1768059

Covello, V. T., & Yoshimura, Y. (2009). The Japanese art of stone appreciation: Suiseki and its use with bonsai. Tokyo, Japan: Tuttle.

Elias, T. S., Gilbert, P., Stiles, R., & Turner, R. (2014). Viewing stones of North America: A contemporary perspective. Warren, CT: Floating World Editions in cooperation with VSANA, Viewing Stone Association of North America.

Elias, T. S., Turner, R., & Harris, P. A. (2020). Contemporary viewing stone display. Claremont, CA: Viewing Stone Association of North America.

Fineman, M. (1996, August 26). Chinese scholars’ rocks: An appetite for significant form. Retrieved December 03, 2020, from http://www.artnet.com/magazine_pre2000/features/fineman/fineman8-26-96.asp

Gallery talk: "Sculpture by nature" Chinese scholars’ stones exhibition at the Weston Public Library [Motion picture on DVD]. (2001). The Friends of the Weston Public Library. https://find.minlib.net/iii/encore/record/C__Rb2065222__SSculpture%20by%20nature__Orightresult__U__X4?lang=eng&suite=cobalt&marcData=Y.

Greenwood, K., & Lakos, R. (2017, August 18). Chinese scholars’ rocks [Video Essay]. Retrieved December 03, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=llJn7YuCoAY

Hay, J. (1985). Kernels of energy, bones of earth: The rock in Chinese art. New York, NY: China House Gallery.

Hu, K. (1998). The spirit of gongshi: Chinese scholars’ rocks. Newton, MA: Published by L.H.

Hu, K. (2002). Scholars’ rocks in ancient China: The Suyuan Stone catalogue. Trunbull, CT: Weatherhill.

Hu, K., & Elias, T. S. (2013). Spirit stones: The ancient art of the scholar’s rock. New York, NY: Abbeville.

Loong, M., & Yee, C. (2019). Four accomplishments in ink: Liu Dan; Master of the Water, Pine and Stone Retreat; Xu Lei; Zeng Xiaojun. Beijing, China: Ink Studio.

Mowry, R. D. (2015, November 23). Collecting guide: Scholars’ rocks: Christie’s. Retrieved December 03, 2020, from https://www.christies.com/features/Collecting-Guide-Scholars-Rocks-6815-1.aspx

Mowry, R. D., & Rosenblum, R. (1996). Worlds within worlds: The Richard Rosenblum collection of Chinese scholars’ rocks. New York, NY: Asia Society Galleries.

Murakami, T. (2005). Little boy: The arts of Japan’s exploding subculture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Rosenblum, R., Doran, V. C., & Rosenblum, A. (2001). Art of the natural world: Resonances of wild nature in Chinese sculptural art. Boston, MA: MFA Publications.

Sheng, H., Scheier-Dolberg, J., & Yang, Y. (2010). Fresh ink: Ten takes on Chinese tradition. Boston, MA: MFA Publications.

Smith, R. (1996, May 31). Old Chinese rocks: Rorschach blots in 3 dimensions. New York Times. Retrieved December 3, 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/1996/05/31/arts/art-review-old-chinese-rocks-rorschach-blots-in-3-dimensions.html

Stuart, J. (2020, November 11). Rocks as art — A Chinese tradition. Retrieved December 03, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OboyFOWTV90

Willis, E. (2020, February 17). Built on rock: The geology at the heart of Oscars sensation Parasite. Retrieved December 03, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/film/2020/feb/17/parasite-viewing-stone-suseok-geology-bong-joon-ho-oscar-best-film