FIGURE 1 | Lyttelton through Bridle Path rockfall (photograph by D. Green, 2011).

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2021) 7(1):71–91 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2021/7/7 |

Enduring Liminality: Creative Arts Therapy When Nature Disrupts

忍受阈限:自然陷于混乱时的艺术治疗

Programme Leader and Research Coordinator Whitecliffe College, Aotearoa/New Zealand

Abstract

Ecopoiesis invites us to become response-able from within our position as part of, rather than separate from, the natural world. What happens, however, when nature disrupts? When being ‘within’ and ‘part of’ becomes disturbing? And, in such situations, what may creative arts therapy offer? When earthquakes struck my home in Aotearoa/New Zealand (2010 onwards), I floundered within my own reactions to nature unchained. And yet, through poietic engagement with natures’ creative and destructive elements, my clients and I found ways to endure and even play within the chaos. I’ve subsequently used arts-based auto-ethnography to chart positionings and practices that may help other therapists to navigate living/working within similarly uncertain situations. In this arts-based exploration, I creatively revisit arts therapy that evolved in response to earthquake disaster and invite wonderings about similar ecopoietic responses to current contexts of COVID and climate change.

Keywords: Enduring liminality, natural disaster, playfulness, communitas, soul

摘要

生态学邀请我们从身处自然之中的立场出发,作为自然界的一部分而非与之分离有所回应。然而,当自然陷于混乱,会发生什么?当身处自然"之中",身为自然的"一部分"变得令人不安,会发生什么?在这种情况下,创造性艺术治疗可以提供什么?(从2020年起)当地震袭击我在新西兰的家时,对自然作出自在的反应让我感到无措。然而,通过对大自然创造性和破坏性元素诗意的了解,我和我的来访者们找到了忍受混乱,甚至在混乱中游戏的方法。随后,我使用基于艺术的自传民族志,描绘定位和实践,这可能有助于其他治疗师在相似的不确定情况下找到应对生活/工作的方式。在基于艺术的探索中,我创造性地重新审视了为应对地震灾害而发展起来的艺术治疗,并邀请大家思考相似的生态诗意的方式,应对当前新冠疫情和气候变化的情境。

关键词: 忍受阈限, 自然灾害, 游戏性, 共同体/共睦态, 灵魂

Before dawn in September 2010, a strong earthquake roared through the province of Canterbury on Aotearoa/New Zealand’s South Island. This “miracle quake” caused substantial damage but killed no one. February the following year, a shallow aftershock struck, violently shaking the city of Christchurch (population: approximately 370,000).

I’m breathing deeply into a tangled tale woven by a client when…

…deep-throated roar

punching through the room

client’s bloodless face, eyes and mouth wide

spilled over by upward-kicking floor

deafening sounds, tortured metal-glass-timber-concrete-humans

huddling semi-foetal, covering heads

finally, the vast beast stampedes off

…frozen silence…

in-rush of wailing sirens/alarms/screaming/car horns/falling glass and masonry.

My client is intact, my studio not—outside wall mostly gone, window in the street. Reception, full of debris, staff and clients cluster. A woman hopping on one foot—putting on shoes. Another clutching her arm—a bloody gash.

The door is jammed. I’m terror-strong and wrench it free. In shuddering gaggles, we hurry downstairs. The street, tortured tarmac, thick dust, dazed people wearing grime. A fierce aftershock. Shouting: ‘Get back from the buildings!’ Facades totter and fall.

My lips are fat. I can barely speak. How to let my partner know I’m OK? To find if he is…? My phone’s under bricks…somewhere.

My client and I walk towards our cars. I’m clutching her arm…reassuring her or me?

We pass fallen buildings. I’m numb.

A huge wreck, haze-shrouded,

flickering through smoke, mirage of a blonde woman

balanced atop the rubble in remnants of suit-jacket and skirt.

Another catastrophic aftershock punches…

When I raise my head,

the ruined building has collapsed further.

The woman is gone.

Shock prevents me accepting people are dying today.

Our cars are intact. I hug my client.

My little green Fiat feels haven-like…

…until the radio tells me the epicentre is Lyttelton, my home.

Cells draining downward, tingling, icy, scarcely able to hold the steering-wheel.

The drive lasts forever. Streets are clogged—those fleeing/fallen buildings/gouts of liquefaction bubbling through ragged tarmac. Yet we’re polite, caring, wanting to reach our loved ones.

But the tunnel and passes are closed. I stand with other Lytteltonites—our only way home is on-foot over the Port Hills. We look at the ascending mist-shrouded track. It kicks up. We ride the aftershock. Cannon-fire erupts high above. Castle Rock explodes, boulders bound thunderously down, carving through fog, spewing dust.

Many turn back. I join the gaggle determined to get home. One man shoulders coils of sisal rope—‘just in case’. Another in expensive suit and pointy-shoes lets me text my partner with his mobile-phone.

I walk. Breathless in damp mist, I’m soon alone.

Cresting, I cross the ridge and descend. An overhanging rock-wall has partially collapsed. Screwing tight, I scamper over razor-edged boulders beneath teetering ledges (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 | Lyttelton through Bridle Path rockfall (photograph by D. Green, 2011).

I turn the final corner. My man is trudging towards me. We run.

We hold each other.

Later, as numbing-shock melts, I learn people were dying all around me.

185 lost their lives—115 in the collapsed hulk of the CTV building,

including,

I assume,

the blonde woman

who vanished into the maw of the large aftershock.1

The earthquakes and their ongoing aftermath cast residents of greater Christchurch into a situation I have come to call enduring liminality. We are threshold communities living amid ruins and road cones as nature reminds us of our transience. As this multilayered disaster unfolded, we turned to the creative arts for succor: ways to express wordless distress, commune with others, re-create and reconnect with and befriend nature at its most destructive. Artists filled vacant post-demolition lots with dancefloors, gardens, performance stages; emblazoned brightly colored murals on condemned buildings; transformed broken shards into glimmering mosaics; curated rows upon rows of white chairs to commemorate those the quakes claimed. And my creative contribution involved group and individual arts therapy for the quake-affected of all ages.

As quakes raged throughout 2011 into 2012, I was the city’s sole registered arts therapist. Fulfilling the responsibility this conferred, however, proved troublesome. My city workspaces were quake-damaged, and my drafty garden shed became my therapy studio. Like many clients, my old psychological wounds reopened to collude with my present-tense, quake-induced, jangling-sleepless-hyperaroused knee-jerk reactivity. My challenging simultaneity as quake survivor and therapist betwixt-and-between destruction and re-creation was foretold by a potent image. Kite-in-the-rubble (Figure 2) arose a few weeks after the February quake as I poietically re-imagined being in the wreckage from which I metaphorically flew a kite—a periscope? A symbol of hope? And I was not alone in this kite-flying—counsellors, psychotherapists, and carers throughout the city also picked themselves up, dusted themselves off, and began work perched within the rubble of their own and their clients’ lives.

FIGURE 2 | Kite-in-the-rubble (pastel by D. Green, 2011).

Throughout 2011, taunted by aftershocks and enmeshed in the acute phase of trauma, many of us suffered exaggerated startle responses, recurring nightmares, distressing thoughts, feelings of detachment, difficulty concentrating, and irritability (American Psychological Association, 2013). Too early to process traumatic memories, we needed emotional and physical stability, safety and soothing, contact and connection (Briere & Scott, 2015). This was not easily achievable amid the relentless aftershocks. My initial multimodal processes to express, explore, and endure were thus group-based activities focused on reconnection, resilience, and achieving what constancy we could in our tumultuous environment (Knill, 2011).

Whenever I facilitated stand-alone group sessions within local schools and organizations (Green, 2012) (Figure 3), I offered one-to-one therapy for those desiring/requiring more. As we emerged from the acute phase and grew familiar with our changed world, many accepted and I worked intensively with numerous individual children and adults.

FIGURE 3 | School postcard-project (photograph by M. Herman, 2011).

In 2015, curious about what my experiences may offer others, I completed a doctorate blending arts-based research and autoethnography (a methodology I have named abr+a; Green, 2016; Green et al., 2018). Repeatedly re-imagining my Kite-in-the-rubble (Figure 2), this PhD explored what it means to live and work within a natural disaster.

Ten years on from the quakes, as globally we struggle with nature unleashed through climate change and COVID, colleagues say:

‘Online searches for nature+arts+therapy+images lead to bucolic mandalas and artworks—benign nature showcased via carefully ordered leaves, twigs, petals, pebbles. Where’s the wildness? The ravaging fire, flood, earthquake, eruption, tornado, drought, disease, gale and hail?’

Then they ask:

‘What forms of arts therapy might help us accept and befriend nature when it is unpredictably destructive?

How did you do it…simultaneously inhabit and offer therapy to others within such upheaval?

Reasonable questions, I tell myself, because I’ve experienced and researched ‘what it means to live and work within a natural disaster’. I should have something to offer others threshing within this deluge of calamities…

…but panic sluices through me…the wreckage from Kite-in-the-rubble becomes a surging ocean. I’m in a wee coracle, clutching my kite-string (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4 | Navigating (digital collage by D. Green, 2020).

I contemplate this felt-sense of I-have-nothing-to-offer. Softening my knees, I centre myself and breathe…

Here I am, still doing topsy-turvy-balancey-therapy-things. How? I don’t feel I’m wallowing rudderless…so what’s guiding me?

Perhaps my encompassing-metaphor of liminality offers sense-making containment, helping me navigate when nature rampages.

Ecopoiesis invites us to become response-able from within our position as part of, rather than separate from, the natural world. But what happens when nature disrupts? When being “within” and “part of” becomes disturbing? In this article, through images and writing, I explore how my pivotal, kaleidoscopic metaphor of enduring liminality birthed five rhizomatic ever-evolving kite-like praxes to guide me upon this queasy ocean. And I hope these may offer an arts therapy that helps orientate other therapists also adrift within similarly volatile situations.

The Ocean: Enduring Liminality

Let us begin with enduring liminality, my central metaphor. Explorations of the betwixts-and-betweens evident in my Kite-in-the-rubble image drew me to anthropologist Turner (1969, 1970). Studying African tribal ceremonies, Turner identified three stages that constitute ritual. The separation phase removes initiates/neophytes physically and metaphorically from everyday society. The liminal phase, usually guided by a ceremony master/shaman, involves mystical symbolic processes to facilitate transformation. The transformed neophytes then rejoin society via the reintegration phase. During the liminal stage, all is mutable and extreme, known social structures and hierarchies are dismantled, and boundaries between worlds and individuals become porous. Liminality thus becomes a fertile metaphor, applicable to various contexts. Harris (2009) and Levine (2009) propose trauma and liminality share characteristics, including fracturing of known structures as well as feelings of limbo and uncertainty. Levine (2009) goes further, suggesting human existence is itself liminal. Waller and Sibbett (2008) view cancer as permanent liminality with the separation of initial diagnosis followed by treatment, remission, and/or recurrence, which interferes with reintegration. Haywood (2012) believes childhood sexual abuse casts the survivor into ongoing liminality.

Liminality, as axial metaphor, illuminated aspects of clients’ and my quake experiences of often-unbearable precarious suspension-in-limbo between a previous normal and something yet to emerge. This was juxtaposed with our heightened feelings of community and tingling frisson of new possibilities. Referencing Turner’s (1970) ritual structure: the quakes violently separated us from our everyday; plunged us into unstable liminal transition; with no identifiable endpoint reintegrating us back into normality. My focus as therapist thus shifted from working toward reintegration—(when will there be a new-normal to re-join?)—toward helping clients endure, in generative ways, this liminal flux unleashed by natural disaster. Five core features evoked within liminality, as identified by Turner, became kites helping me make sense of how arts therapy fostered this endurance. These are: building soul; negotiating chaos and control; embracing the wounded|healer archetype; skipping into playfulness; and nurturing communitas (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5 | Five-kites (digital collage by D. Green, 2020).

Kite 1: Building soul

I take my soul for a stroll

We agree with Mary Oliver’s wild wisdom

that soul is built from attentiveness

So, me-and-my-soul are attentive

To blue arc of sky

To crunchy gravel skittering underfoot

To hum of harbour throbbing below

To splinters of sun on water

To dogs rummaging in tangled undergrowth

To swoopy-whoop of magpies

To heave of breath in our body

To being embodied

To being ensouled

To being

I was confused when I began offering quake-arts therapy. Was I helping untangle snarled thoughts? Or soothe jangled bodies? Or settle tumultuous emotions? Yes…all of this…and…something more, something deeper, something existential. Something that’s tangibly evoked when, tumbled into ambiguous life-threatening situations by the unpredictability of nature, we’re reminded how illusionary our control is. Words attributed to Thoreau illuminated the dusty corners of my dilemma:

As arts therapist, my realm is the arts. The arts’ realm is imagination. Imagination’s realm is soul. Soul’s realm is liminal. My first kite takes flight.

Ritual liminality, traditionally associated with soul and spiritual practices, enables souls to cross thresholds and connect with each other, the dead and non-human beings, and call upon mystical transcendent powers/beings to intervene, assist and/or bless transitions (Harris, 2009; Turner, 2004). As arts therapist, I am working with soul. As therapist within liminality, I am working with soul. As arts therapist working within the enduring liminality of disaster, through creative expression of wounds inflicted on imagination, I am helping clients transmute soul suffering. By ensouling arts therapy, I evoke “something both human and timeless” (Fox, 2014, p.135). I thus attend to what links the roiling ocean (temporal/corporeal/human) and the kites (timeless/transcendent/numinous) within ourselves and our liminal context.

To attune myself to the multifarious interpretations of soul by clients, I must first understand my own. During the quakes, clients and I returned time and again to a practice I describe as dropping-in to find out what our souls are doing. This blends focusing-oriented arts therapy (Rappaport, 2008) with McNiff’s (2004) communing with images as messenger-angels. I do this now: tuning into my senses, I drop inward and my felt-sense of soul arrives in images and words (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6 | Soul (digital collage by D. Green, 2020).

Soul—I cringe. But what other word is there? Elan vital? Chi? Energy? Ever-open-edge? Definitely something more than ‘brain’, which is merely the substratum (Gendlin, 1997).

Soul is murmuration, limberation, magnetism, a more-than halo connecting and radiating beyond the sum-total of mind/body/affect.

Soul is tentacular, Indra’s net, entangled rhizomes, meshwork linking imagination+intuition, a chorus of selves. Soul kaleidoscopically jumbles relativism&universal-truths|sense&doubt-about-the-sense-of-it-all|hope&melancholy|sincerity&irony|naivety&cynicism|construction&deconstruction.

Soul stays with the trouble and nuisances absolutes—both eternal and temporal|collective and individual|shadow and light|intricately-granulated and all-encompassingly-global|whole and fragmented…& all of these complexicatingly shimmying beyond words…towards something-more—a liminal|post-postmodern multiplicity I call ‘both-and-&’

Yes.

Working with soul requires a sense of wonder.

Soul-based ways of being/working recognize, in unstable situations, outcomes cannot be known in advance. Rather, we therapists palpate the unknown and must remain attentive to what arrives. As life does not have one fixed meaning, we must allow images to gesture beyond all given meanings by not translating complex processes and imagery into simplistic this-means-that rationalizations. Staying with soul and allowing images to animatedly walk about on their own legs (Hillman, 1983) engages imagination, troubling notions that art provides logical meaning in extreme anguish. The chaotic meaninglessness of suffering may only find adequate form through poietic expression. Distress, alchemized by the creative act of repeating it differently, allows remembering to become a form of imagining. This channels our creative capacity to shape experience. Suffering is not minimized or eliminated but gifted with new meaning through the metamorphic act of imaginative soul-building (Levine, 2009).

Such soul-building emphasizes limberness. Researching my quake-work revealed how imaginative restoration nurtures flexible souls which enable head/heart/body to endure the surging seas of disaster-induced liminality and still call “Yes!” to life. Such soul nimbleness resonates with Kass and Trantham (2014), who identify re/creation of internal composure as central to trauma healing. This enables us to engage and withdraw as needed for growth and defense, helping us ride strong, troubling emotions without these seizing control. As those suffering often lose internal composure and experience dysregulated triggering of the stress response and/or immobilization, nourishing soul-limberness is pivotal within ensouled therapy.

Stretching exercises for limber souls: A therapists’ guide

Prepare to use all the arts.

Profusely.Activate your own imagination.

Your capacity to imagine awakens empathetic connection with others,

it’s how you learn from them and transform yourself, and

how you invite imaginatively-shut-down clients into sympoiesis.Reach into your intuition.

This channels previous knowledge and experience,

to seek and predict patterns, and

awaken archetypes from the collective unconscious.Breathe deeply into soul/body connections.

Heed the ancients who suggested

our fundamental experience of the world is sensual

and therefore aesthetic (Levine, 2009).

Heed contemporary evidence suggesting

vagal toning and nervous system soothing

begins with attention to body and breath (Levine, 2010).

Use your own embodied imagination+intuition

to inspire clients’ imaginations.

Collaborate, co-quest, co-create.

Make-strange, decenter into the alternative logic of creation.

Share your felt-sense of what’s arriving.

Invite clients to do the same.

Respond aesthetically with

descriptive words, movement, arts-making.

Invite the artworks into dialogue.

Listen and create again.Revel in this flexible co-creative sympoiesis

of embodied inspiration+imagination+intuition

animating limberness and nurturing soul.

Kite 2: Negotiating chaos and control

My ensouled both-and-& resonates with ways liminality evokes simultaneity of power and powerlessness (Turner, 1969). I manifest this power paradox through wrangles with control and chaos—unsurprising as control, loss of control, and chaos are core experiences connected to trauma (Herman, 2001; Levine, 2010).

Disaster fractures known structures, tossing clients and therapists alike into liminality (Figure 7) where we are prey to the archetypes of powerless neophyte and controlling shaman. We become neophytes stripped of previous roles and structures, but alive to possibilities for metamorphosis (Turner, 1970). Although destabilizing, the disempowerment of the neophytes’ sacred poverty is not solely deconstructive. It can facilitate transformation, reshaping old elements in new patterns via holistic “change in being” (Turner, 1970). Unlike the neophytes’ comprehensive shared equality, the shaman wields complete authority through hallowed symbols and rituals. The fricative duality experienced by therapists embroiled in disaster, however, disrupts the traditional shaman’s power to grind-down and make-anew the naïve neophyte. Therapists within disasters are permeated by both archetypes, becoming neophyte|shamans. During the quakes, I was simultaneously trained-therapist/shaman and quake-survivor/neophyte alongside my clients. This nettled the objectivity construed as crucial to ethical therapy (ANZACATA, 2019). Teetering betwixt-and-between the complete authority and complete equality governing traditional shaman-to-neophyte and neophyte-to-neophyte relationships, I strove for relational dynamics grounded in a sense of different-but-equal.

FIGURE 7 | Betwixt-and-between (digital collage by D. Green, 2020).

This different-but-equalness invites careful consideration of the chaos-control dialectic embedded within psychotherapeutic constructs underpinning our work. The more rationally planned approaches, such as biomedical and cognitive-behavioral models, assume therapy is the controlled application of logical solutions to clearly defined problems. The complexity of disaster situations, however, often resists rational explanation and predictability. In addition, human neurological responses suggest that traumatic experiences rupture our capacity to corral this overwhelm into the logic of language (van der Kolk, 2014). Thus, despite enabling the therapist to feel in control, rationally planned approaches can be misguided because they focus on solving a problem rather than curiously pursuing the “mystery” (Mølbak, 2013). A process-oriented approach welcomes this mystery, believing therapy cannot be preplanned. The therapist does not seize control but opens ongoing dialogue with the therapeutic situation, continuously revising engagements based on responsiveness to what is emerging.

When I began my quake-work, I attempted to apply a rational-planning approach. The assumption that my clients’ individual’s difficulties could be objectified as concrete problem behaviors that are discrete instances of universal obstacles, often silenced their personal worlding. Clients and I swapped the mystery for tamed experiences that could merely be integrated into preexisting worldviews circumscribed by what is already known. The problem thus often resurfaced later. I came to learn, however, that “good” therapy “unleashes an unpredictable future” (Mølbak, 2013). Something new, that cannot be known in advance, needs to happen to arouse this “other future”. Therapy seeking this is not defined by fixed starting points and projected end states—it attends to the middle, the liminal-kite-string-space from which new pasts and new futures may arise.

This process-oriented approach troubles appealing fantasies that therapists produce desired outcomes by selecting and controlling the right means (Levine, 2009; Mølbak, 2013). Combine this with disaster-induced enduring liminality and we have a call for poiesis—our capacity to respond to and change the world through shaping what is given (Levine, 2009). Rather than impose order onto formlessness, practicing poiesis invites intrinsically unique form to emerge from turmoil. This enhances our response-ability to the chaos into which disaster topples us. Creatively poietic processes change passive experiences into active ones, bringing us into the present moment and transforming us from those who are done-to into the doers (Levine, 2009).

Loitering within chaos until new order emerges can be unsettling—especially when our instinctive reaction often escalates attempts to restore order through increased control. As quake-neophyte|shaman, careful containment helped me resist this will-to-control while acknowledging our fear of stirring-up further mayhem. Murphy’s (2014) research with disaster-responders supports this, concluding that art therapy can transform disempowered victims into empowered survivors by providing containment during often chaotically uncontrolled experiences of ongoing disaster. Containment feels more generative than order or control and the provision of a safe container by the therapist features in most therapeutic approaches (Levine, 2009; McNiff, 2004; Rappaport, 2008). We arts therapists may use various physical and metaphoric creative containers, including the therapeutic relationship; arts-materials, arts-processes and arts-products; our imaginations; good supervision; and how we hold and embody our own wounding and healing.

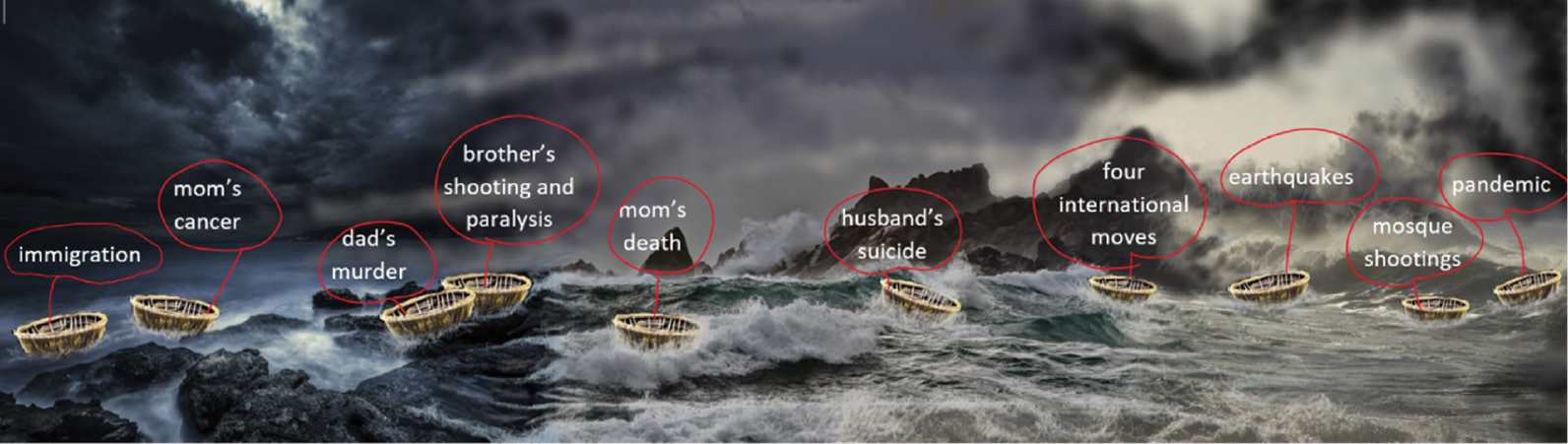

Kite 3: Embracing the wounded|healer archetype

Alongside the chaos-control-wrangling neophyte|shaman, liminality awakens in therapists the archetypal wounded|healer.

I’m learning to creatively-be with my wounding life-experiences (Figure 8). I believe this enables me to hold space for clients to be with their own hurt. I’m also living into my own healing, salvaging this often-submerged aspect of the wounded|healer archetype—foregrounding ways I embody wellness for clients. I inhabit the fertile tension of Kapitan’s (2020) ecotone—where two distinctly different environments meet, creating a third, transitional/liminal place of possibility. I’m riding the roiling sea in empathy with clients’ pain, I’m flying a dancing kite-of-healing…and spanning between, I lace and hold a limber response-able string.

FIGURE 8 | Wounding timeline (digital collage by D. Green, 2020).

Woundedness is often figural within a shaman’s calling. In various cultures, shamans (and sometimes, priests and prophets) come into their vocation via suffering and healing from illness or wounding. This wounded|healer shaman has credibility as one who knows suffering, can voluntarily journey into alternate worlds, encounter disturbing spirits, and emerge stronger and wiser to serve others as soul-healer (Jackson, 2001; Martin, 2011).

Disasters are devils for re-gouging old hurts which then exacerbate present-moment suffering. During the quakes, I initially worried that practicing therapy as hybrid neophyte|shaman+wounded|healer was unethical and unsafe. I soon discovered, however, clients wanted assurance that I too knew quake-related fear and that my past pain had also woken to haunt me afresh. Many spoke of outsiders who “didn’t get it” and a culture evolved suggesting only those pummeled by quakes fully comprehended our plight. Alongside suffering, however, I also know healing and the quakes encouraged me to value my ongoing healing as essential to my practice. Far from being broken by the pain that existence can deliver, the wounded|healer welcomes life’s brightness and brilliance. Journeying toward healing connects the wounded|healer more powerfully with their own élan vital/chi in a life-forward direction.

I use healing in preference to recovery. Recovery hosts curative connotations, suggesting return to an illusory Eden with no splits or conflicts (Levine, 2009). In previously seeking return to this wholeness, I had rejected bits of me I could not incorporate. I only began healing when, rather than attempting to exorcise suffering, I embraced my intrinsic fragmentation/multiplicity by recognizing the ecopoietic necessity of both creation and destruction. Suffering thus becomes a valued part of lived experience that has plumbed depths of despair and “encompasses the finitude of existence. It is an affirmation of existence that sees suffering and death as intrinsic to it and nevertheless says ‘Yes!’ to life” (Levine, 2009, p.53).

Calling “Yes!” to occupying the liminal-ecotone alongside clients is not without risk of transgression. Therapeutic relationships are cultivated for a specific purpose, and yet, as fellow-quake-sufferer, I faced post/ongoing-disaster situations that blurred many boundaries. Through good supervision and full acknowledgement of my status as neophyte|shaman+wounded|healer, I embraced how carefully considered boundary-crossings can increase therapeutic effectiveness by enhancing the therapeutic alliance—the best predictor of therapeutic outcome (Hubble, Duncan, & Miller, 1999). In this alliance, the wounded|healer moves from objectivity into intersubjectivity. Theories of intersubjectivity, intercorporeality, and co-regulation propose we entangle with others somatically—in effect, we share nervous systems with our clients (Malchiodi, 2020).

I often sense all-of-me communicating with clients.

My body and soul know anguish and loss,

I quiver and resonate to clients’ pain.

Pay attention, I remind myself, be response-able not reactive.

My body and soul also know healing,

I thrum and quicken to clients’ nascent wellbeing.

Pay attention, I remind myself, be open, be with and model Yes!-ness.

Hold this all gently, even playfully, I tell myself,

And don’t use clients to scratch the scabs of your own wounds…

Kite 4: Skipping into playfulness

Liminality resists control and incites play (Turner, 1970)—hence my reminder-to-self to hold this “even playfully”. A potent and poignant counterbalance to wounding, this playfulness often has me calling “Yes!” to life, infusing my practice with vitality.

Perched together,

toes-digging-into-wet-sand,

peering up the beach

at a messy mandala…

artfully-assembled swirls of seaweed/shells/driftwood/pebbles/small black flies

-and footprints-

Hers-mine-hersmine-hersminehersmineherminhemihmhmhm (Figure 9)

FIGURE 9 | Playfulness (digital collage by D. Green, 2020).

We sprinkle words:

’Precarious’ ’Confusing’ ’Tangley’

’Brave’ ’Challenging’ ’Loosening’

Suddenly sentences:

’I’m playing in the ruins of my life. I’m breathing.

I’m finding new ways to be me.’

Eyes meeting,

we smile.

We nod.

Yes!

Imagical play is the name I’ve given to ways being playfully imaginative with imagery may invite metamorphic magic into therapy (Green, 2017). Imagical play values being permissive and nondirective, co-creatively frolicsome and sometimes provocative. Playfulness helps us “decenter”—to “move away from the restricted experience of conflict and crisis…into the opening of the surprising-unpredictable-unexpected” (Knill, 2011, p.55). Playful decentering ushers us into the realm of imagination where we encounter an alternative experience of worlding that can be harvested for innovative knowings that help loosen habitual stuckness (Levine & Levine, 2017). When the therapist takes tender responsibility for containment, arts-creation and relationship-creation may become “participation in not-knowing” (Levine, 2009, p.111). This experimental playfulness is especially suited to enduring liminality because “playing in the ruins” (Levine, 2009) enables us to relinquish control and stay with formlessness until new order emerges. Imagical play does this in several generative ways. It activates embodied sense-awareness, which grounds us in the present-moment and provides rich material for poietic expression. Interweaving calm-mindfulness with energetic-playfulness cultivates flexibility. This capacity to remain emotionally supple in the face of forces that cause unhelpful contraction and/or dispersal, helps increases our window of tolerance (Malchiodi, 2020). Playfulness ignites bespoke processes and outcomes. As each wounding experience is distinctive, imagical play supports individuals to express, bless, and alter their unique wounds in personalized ways. Imagical play thus helps us reconfigure troublesome memetic patterns forged by suffering and reconnect with the life force in ourselves and others.

Kite 5: Nurturing communitas

Trauma disempowers and disconnects. Creating/re-establishing internal and external bonds, through re/connection and relationship, is core to therapeutic healing—“being-with-others” is how we are “restored to ourselves and thereby transformed” (Levine, 2009, p.45). Within liminality, being-with may evoke communitas, a unique healing state of full communion and heightened acceptance (Turner, 1969). Released from everyday structural conformity, neophytes may form a valued sense of “undifferentiated, egalitarian…nonrational, existential” oneness (Turner, 2004, p.98). Although this eliminates divisiveness, identities are not merged, and each individual’s gifts are fully and uniquely alive.

During the quakes, I experienced many manifestations of communitas with clients, colleagues, my supervisor, nature, and myself in group, dyadic, sympoietic, internal and transpersonal forms. Group communitas resembles a collective manifestation of flow-state (Waller & Sibbett, 2008). When people collaborate wholly, they may enter flow-state as action and awareness merge, the self becomes irrelevant and “what happens is…seamless unity” (Turner, 2004, p.99). This flow-inducing togetherness feels magical—charged with delight and laughter—and it releases helpful neurotransmitters including norepinephrine, dopamine, anandamide, serotonin, and endorphins (Kotler, 2015).

Dyadic communitas may happen within one-to-one therapy and is simultaneously facilitated and nuisanced by the therapist-as-neophyte|shaman power paradox. This complexity may be held by presence. A vital gift from therapist to client, presence questions beliefs that efficient therapy requires frustration of human desires for reciprocity. As intersubjective models gain traction within contemporary psychotherapy, it is increasingly recognized that remaining neutral is distorting and, instead of opening space, can powerfully communicate non-presence (Stechler, 2000). Intersubjective approaches entail the therapist becoming emotionally present to/with the client. Rather than “self-disclosure”, words whose pejorative and erotic connotations compromise discussion, Stechler (2000) proposes “affective-presence”, suggesting we share our inner self more generatively through our emotional responses than via narrative facts.

The arts can help engage and express affective-presence, offering another form of connectivity I call sympoietic communitas. I borrow sympoiesis, meaning “making-with”, from Haraway (2016) to acknowledge the intricate tentacular imbrication of I-make-the-art-and-the-art-makes-me. Sympoietic communitas expands beyond the arts to include our relationship with nature—I-am-of-nature-and-nature-makes-me. Natural disaster can, however, fray this bond. Treating our natural environment as art invites us into poietic presence with/to/through nature. As art aims to a/effect the viewer, we can open to the impact of art/nature and respond in ways that are effectively affective, possibly also aesthetic (Levine, 2009; McNiff, 2014). Active imagination invites us to approach both artworks created in session and nature as ensouled and to encourage these angels to speak (McNiff, 2004, 2014).

My capacity to embody presence to nature, clients, and the arts hinges upon my presence to self. To ensure my affective presence is genuine but contained, it is crucial I am in a lively relationship with myself. Cultivating my presence to self allows me to create/co-create containers to hold and translate clients’ chaos into art and the beginnings of tragic wisdom. Practicing intrapersonal connections within myself invites internal communitas and helps me nurture this in clients. This dynamically inclusive compassionate relationship with one’s embodied inner life is a core theme within psychotherapy. Jung (1953) believed knowing and enriching one’s inner life is vital for therapist and client. Frankl’s (2004) “intensification of inner-life” helped him and fellow concentration camp prisoners survive World War II. Gendlin (1997) and Rappaport (2008) developed focusing/focusing-oriented arts therapy to enliven this inner life and nourish a life-forward direction in therapist and client. Inviting internal communitas offers both-and-& healing connections with self. This expansive inclusion does not homogenize bits of self but befriends each fragment, no matter how oppositional, welcoming the gifts of all. When client and I are (soul)fully present-to-self-and-nature-and-arts-and-each-other, the healing alchemy of communitas manifests—and this is soul-building.

Circling back to soul as pivotal opens possibilities for communitas in relationships with intangible presences. Transpersonal communitas refers to communion with those we carry in our bones—ancestors, ones we’ve lost and mourn, those ghosting us (Green, 2019). Rejecting Freudian perspectives that post-mortal connections need relinquishing, “continuing bonds” invites celebration and/or exploration of what is unseen but still present (Root & Exline, 2014). Within enduring liminality, many clients find release and solace by fostering communitas with presences that hover and haunt.

Nurturing this capacity for variegated communitas is an embodiment of my wounded|healing, representing vital engagement with chaos and control and a both-and-& multiplicit view of soul fostered through imagical play (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10 | Communitas (digital collage by D. Green, 2020).

A clutch of kites

Navigating the enduring liminality of natural disaster requires an arts therapy that, like an array of flexible kite-strings, spans betwixt-and-between the immediacy of roiling ocean and the nimble far-seeing kites. It is an ecopoietic therapy through which we grow able to respond with limber Yes!-ness to what is given and thus ride our fragile coracle across heaving swells of ongoing uncertainty. It recognizes that disaster wounds imagination and soul: the first kite therefore tugs toward soul-building. Through the arts, this therapy embraces and restores a variegated enlivened sense of soul. Kite 2 responds to paradoxical liminal entanglements of power and powerlessness, manifesting in ways disaster has us grappling with control and chaos. This kite calls therapists to acknowledge and negotiate tensions between their in-it-with-clients neophyte position and their conferred power as expert/shaman. This hybridity evokes kite 3, the archetypal wounded|healer impelling therapists to befriend their wounding and engage with their own healing. These complexities require an arts therapy that holds lightly, celebrating ways liminality may ignite playfulness to endure chaos. This fourth kite incites decentering into alternative worlds of imagination. Such playfulness is relational, liberating communitas, kite 5. This alchemical healing sense of flow-inducing communion can be nurtured within groups, in dyadic sessions, sympoeitically with nature and arts-works, with internal bits-of-self and transpersonally with the unseen. Five kites, attached to a bobbing coracle with dancing limber strings, offer a life-forward direction as we strive to navigate uncharted passages across stormy oceans of disaster by accepting and befriending nature in all its wildness.

About the Author

Deborah is programme leader and research coordinator in Creative Arts Therapy at Whitecliffe College, Aotearoa/New Zealand. Her academic/practitioner career encompasses educational/community theatre, adult education, community development, lifeskills/AIDS education and counselling (South Africa 1990–2004), and creative arts therapy (New Zealand 2006–) including gaining a doctorate exploring her practice during the Canterbury earthquakes. A passionate therapist, educator and arts-based researcher, she’s published and presented in/at several international journals/books and conferences/symposia. Email: deborahg@whitecliffe.ac.nz

1 In addition to lives lost, more than 7000 suffered injuries, with 280+ treated for major trauma at Christchurch Hospital. Buildings, roads, infrastructure, and surrounding hills suffered massive damage. This February 2011 tremor unleashed swarms of fierce aftershocks. Amidst the 11,000+ detectable aftershocks, three had a magnitude of 6+ on the Richter scale and more than 670 had a magnitude of 4+. In Christchurch, 1300+ public buildings and 7000+ residential homes have been or will be demolished, and economists have estimated that costs will soar over $40 billion and that Aotearoa will take between 50 and 100 years to recover (McSaveney, 2014).

References

American Psychological Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. APA.

ANZACATA. (2019). Ethics and standards. ANZACATA. Available online: https://www.anzacata.org/ethics-and-standards (accessed 30 September 2020).

Briere, J. N., & Scott, C. (2015). Principles of trauma therapy: A guide to symptoms, evaluation, and treatment, 2nd ed. Sage Publications.

Fox, J. (2014). Poetry therapy, creativity and the practice of mindfulness. In L. Rappaport (Ed.), Mindfulness and the arts therapies: Theory and practice. Jessica Kingsley, pp. 129–141.

Frankl, V. E. (2004). Man’s search for meaning. Ebury Publishing.

Gendlin, E. T. (1997). Experiencing and the creation of meaning. Northwestern University Press.

Green, D. (2012). Clearing a space. ANZJAT, 3(1), 42–51.

Green, D. (2016). Quake Destruction/Arts Creation: Arts Therapy and the Canterbury Earthquakes, Doctoral Thesis, University of Auckland: Auckland, NZ.

Green, D. (2017). Imagical play: Arts therapy and trauma. In P. O’Connor & C. Rozas Gómez (Eds.), Playing with possibilities. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 200–222.

Green, D., Pears-Scown, N., Weir, M., Csata, I., Heney, R., McGeever, M., et al. (2018). The arts of making sens/e. ANZJAT, 12(1), 112–130.

Green, D. (2019). Communitas and soul-healing: Arts therapy within the loss-upon-loss of natural disaster. In M. J. M. Wood, B. Jacobson, & H. Cridford (Eds.), The international handbook of art therapy in palliative and bereavement care. Routledge, pp. 340–356.

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Harris, D. A. (2009). The paradox of expressing speechless terror: Ritual liminality in the creative arts therapies’ treatment of posttraumatic distress. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 36(2), 94–104.

Haywood, S. L. (2012). Liminality, art therapy and childhood sexual abuse. International Journal of Art Therapy, 17(2), 80–86. doi:10.1080/17454832.2012.687749

Herman, J. L. (2001). Trauma and recovery: From domestic abuse to political terror. Pandora.

Hillman, J. (1983). InterViews: Conversations with Laura Pozzo on psychology, biography, love, soul, the gods, animals, dreams, imagination, work, cities, and the state of the culture. Spring Publications.

Hubble, M. A., Duncan, B. L., & Miller, S. D. (1999). The heart and soul of change: What works in psychotherapy. APA.

Kapitan, L. (2020). Arts therapies in the ecotone: Contact, collaboration, and creative entanglement [PowerPoint slides]. Lecture to MAAT students.

Kass, J. D., & Trantham, S. M. (2014). Perspectives from clinical neuroscience: Mindfulness and the therapeutic use of the arts, in Mindfulness and the arts therapies: Theory and practice, edited by Laury Rappaport. Jessica Kingsley, pp. 288–315.

Knill, P. (2011). Communal art-making and conflict transformation, in Art in Action, edited by Ellen Levine & Stephen K. Levine. Jessica Kingsley, pp. 53–77.

Kotler, S. (2015). The neurochemistry of flow states. Think big. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aHp2hkue8RQ (accessed 20 June 2020).

Jackson, S. W. (2001). Presidential address: The wounded healer. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 75(1), 1–36. doi:10.1353/bhm.2001.0025

Jung. C. J. (1953). Fundamental questions of psychotherapy. In R. F. C. Hull (Trans.) and H. Read, M. Fordham, G. Adler, & W. McGuire (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung: Volume 21. Princeton University Press, pp. 111–125.

Levine, E. G., & Levine, S. K. (2017). New developments in expressive arts therapy: The play of poiesis. Jessica Kingsley.

Levine, P. A. (2010). In an unspoken voice: How the body releases trauma and restores goodness. North Atlantic Books.

Levine, S. K. (2009). Trauma, tragedy, therapy: The arts and human suffering. Jessica Kingsley.

Malchiodi, C. A. (2020). Trauma and expressive arts therapy: Brain, body, and imagination in the healing process. Guilford Press.

Martin, P. (2011). Celebrating the wounded healer. Counselling Psychology Review, 26(1), 10–19.

McNiff, S. (2004). Art heals: How creativity cures the soul. Shambala.

McNiff, S. (2014). The role of witnessing and immersion in the moment of arts therapy experience, in Mindfulness and the arts therapies: Theory and practice, edited by Laury Rappaport. Jessica Kingsley, pp. 38–50.

McSaveney, E. (2014). Historic earthquakes—The 2011 Christchurch earthquake and other recent earthquakes. Te Ara. Available online: http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/historic-earthquakes/page-13 (accessed 30 September 2020).

Mølbak, R. L. (2013). Cultivating the therapeutic moment: From planning to receptivity in therapeutic practice. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 53(461), 461–488. doi:10.1177/0022167812461305

Murphy, C. S. (2014). Post-disaster group art therapy treatment for children, Master’s Thesis, Loyola Marymount University.

Rappaport, L. (2008). Focusing-oriented art therapy: Accessing the body’s wisdom and creative intelligence. Jessica Kingsley.

Root, B. L., & Exline, J. J. (2014). The role of continuing bonds in coping with grief: Overview and future directions. Death Studies, 38(1), 1–8.

Stechler, G. (2000). Louis W. Sander and the question of affective presence. Infant Mental Health Journal, 21(1–2), 75–84.

Turner, E. (2004). Rites of communitas. In F. A. Salamone (Ed.), Encyclopedia of religious rites, rituals, and festivals. Routledge, pp. 97–101.

Turner, V. W. (1969). The ritual process: Structure and antistructure. Aldine.

Turner. V. W. (1970). The forest of symbols: Aspects of Ndembu ritual. Cornell University Press.

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Group.

Waller, D., & Sibbett, C. H. Editors. (2008). Art therapy and cancer care. KakJiSa Publisher/OUP.