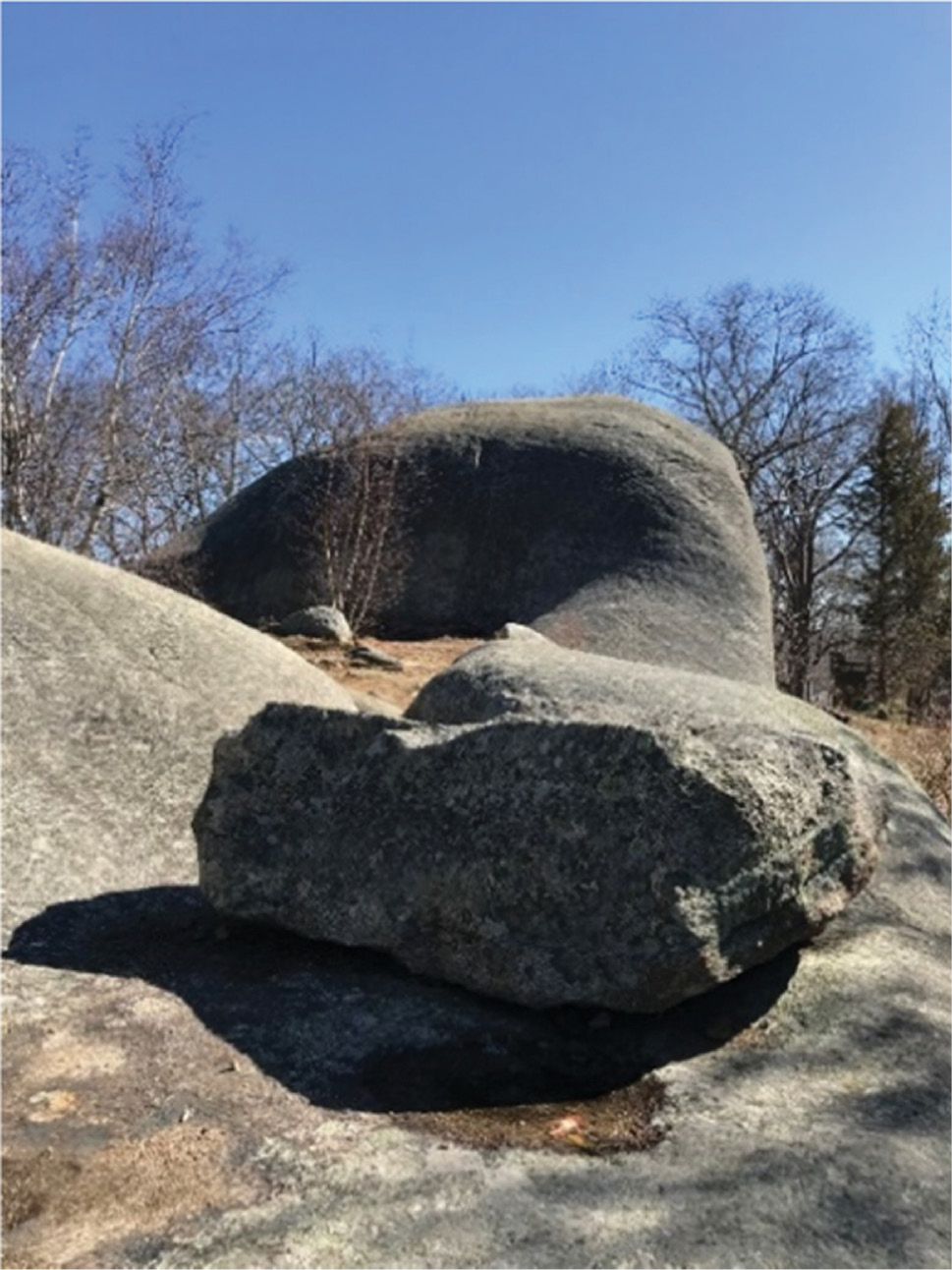

FIGURE 1 | Glacial granite 1.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2021) 7(1):3–9 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2021/7/5 |

Art and Stone: An East, West, and Global Perspective

艺术与石头:东西方全球视角

Lesley University, USA

Abstract

Introductory comments and reflections on the Donna Dodson and Jun Hu articles in the current issue of CAET dealing with scholars’ rocks and rock balancing art. The artistic approaches to the stone configurations are presented as accessible and transcultural forms of artistic expression that have a worldwide aesthetic appeal.

Keywords: scholars’ rocks, rock balancing art, environmental art, cairn construction, universal forms of artistic expression, accessible art expression

摘要

此文介绍了本期CAET中Donna Dodson和胡俊涉及君子石和岩石平衡艺术的文章,并加以评论和反思。文章展示了构建石头形态的艺术方法是人们可接触到的跨文化的艺术表达形式,具有世界性的审美吸引力。

关键词: 君子石,岩石平衡艺术,环境艺术,穴居建筑,艺术表达的普遍形式,无障碍艺术表达

When I received the announcement for the exhibition curated by Donna Dodson at the Korean Cultural Center in New York, Interpreting the Natural: Contemporary Visions of Scholars’ Rocks, I proposed to the CAET editorial team that we invite her to write an article reflecting on the East Asian tradition and how it relates to worldwide artistic interest in natural rock formations as exemplified by the show. I felt that this project perfectly fit the mission of the journal in presenting a classical East Asian art practice together with its influence on contemporary Western artists. As I worked with Donna Dodson on the article, I realized how the depth of her vision and understanding, in my view, embodies the purpose of this journal and its focus on Eastern, Western, and global perspectives. I say this not just from my editorial commitment to the journal’s mission supporting scholarship exploring how East Asian traditions and artistic practices further appreciation of common human experience, but also as an artist with a long standing relationship to stone.

I live and work in the Cape Ann region of Massachusetts, where ancient glaciers carved granite formations that not only permeate the landscape but resulted in the early 19th century quarrying of the stone. My studio is less than 10 feet from the configurations shown in Figures 1 and 2, and the property is surrounded by mid-19th-century stone walls likely cut on site (Figure 3) (all photographs were taken on March 29, 2021).

FIGURE 1 | Glacial granite 1.

FIGURE 2 | Glacial granite 2.

FIGURE 3 | Cut granite wall.

Since I am a scholar and painter of rocks and close neighbor to them, I may inadvertently be considered as someone who can speak to the subject of “scholars’ rocks.” For the past three decades, my art has responded to this natural environment as documented in my 2009 artist’s video Under Squam Rock.

My experience supports Donna Dodson’s emphasis on the “living nature of stones” and how the tradition of scholars’ rocks eliminates the Western dichotomy between so-called abstract art and nature. In addition to distinct non-abstract parallels between scholars’ rocks and contemporary non-figurative sculpture and painting, every form of art-making that “represents” nature, no matter how literal the composition, involves an elemental abstracting process in creating the piece. Although often de-emphasized in this era of one-sided focus on cultural differences, there are aspects of experience that are shared by the human community. The scholars’ rocks tradition and its worldwide appeal offers elegant and compelling art evidence of universal sensibilities (McNiff, in press). With the deepest respect for the infinitely unique qualities of human cultures and individual lives, all of which correspond to the realities of the natural world, I believe there are also features of experience that characterize the whole of humanity and organic life (McNiff, 2018).

As I prepared to write these reflections, I visited a site just above my studio to photograph a free-standing granite rock that is part of a larger stone complex. This rock (Figure 4) and its placement within the landscape created by glacial activity thousands of years ago (Figure 5) has been a been a focal point in my painting, imagination, and sense of place. I felt that the rock and its setting would help further a firsthand immersion in the tradition of scholars’ rocks and how they can exist in every part of the world.

FIGURE 4 | Squam Rock 1.

FIGURE 5 | Squam Rock 2.

Unrelated to the journal’s planned article on scholars’ rocks, we recently received Jun Hu’s “Rock Balancing Land Art: A More-than-Human Approach” for inclusion in the special issue coordinated by Tony Zhou focused on Revitalizing the Practical Application of Wisdom Embedded in Nature. I was giving thought to how I could integrate this contribution into my reflections on Donna Dodson’s article since I felt that the two were closely attuned. As I approached the site, I saw that someone had recently constructed balanced rock structures (Figures 6 and 7) like those presented by Jun Hu.

FIGURE 6 | Rock balancing 1.

FIGURE 7 | Rock balancing 2.

In 30 years, I have not seen anything like this on the property, and I encountered the stacked stones just minutes after looking at the images in the rock balancing article showing many pieces like this pair. The synchronicity and art evidence convincingly present the transcultural human and artistic principles that I strive to articulate.

Jun Hu from Hangzhou, China, documents experimentation with Inuit informed rock art configurations, in Montreal, Canada, not too far north of Donna Dodson and myself in Massachusetts. His work speaks to me about shared human feeling. The Inuit tradition has close affinities to Celtic cairn construction and what might be viewed as the innate way that the materials themselves and their worldwide existence in nature, together with the involvement of gravity, motivate and suggest the balancing and shaping processes. The pre-existing natural substances invite a human response. As I repeatedly see in my studio work with others, the making of new connections and relationships with already formed nature artifacts is a rich and accessible form of artistic expression. In contemplating the materials, they influence what we do with them. We follow their lead with our esthetic and imaginative sensibilities and responsive actions. The building process is universally accessible and relatively simple, and it requires patient and thoughtful experimentation, cooperating with the forces of physics.

In helping people to become involved in all forms of artistic expression, I encourage them to approach the experiences as co-creating with nature, which includes themselves, their materials, and subject matter. It contradicts reality to assume that the maker of art is separate from nature, an attitude that is no doubt a source of the alienation at the root of so many human discontents (McNiff, 2021). These life-sustaining art and nature medicines are also explored in this issue by our editorial board member Alexander Kopytin, who is advancing “nature-assisted” approaches to art in health (Kopytin & Rugh, 2017). Although the process of making configurations with stones gathered in a particular place, as with other forms of environmental art, can be considered as on the more concrete and self-evident end of the spectrum of artistic creation’s integral relationship with nature, I believe the connectedness applies to all forms of art.

Appreciation of scholar’s rocks and constructions made from stones found in our environments show how every sensitive and curious person, of all ages, can both discover and make elegant objects, co-created with nature. While affirming infinite differences in creative and imaginative expressions, these processes manifest shared human sensibilities. On a worldwide basis, I witness how the construction of art objects with materials from nature reliably evokes a palpable sense of the sacred. In asking why this happens, I believe it may have atavistic connections to our most fundamental aesthetic feelings in relation to the natural world together with the ritual dimensions of making and sharing these creations in community with others. People everywhere can access these healing properties of artistic action and perception so generously offered by the environments in which we live. The process is good medicine for the human community and the soul of the world that holds us all.

About the Author

Shaun McNiff, University Professor Emeritus, Lesley University, Cambridge, MA, USA. Email: smcniff@lesley.edu

References

Kopytin, A., & Levine, S.K. (Eds.). (in press). Ecopoiesis: A new perspective for the expressive and creative arts therapies in the 21st century. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Kopytin, A., & Rugh, M. (Eds.). (2017). Environmental expressive therapies: Nature-assisted theory and practice. New York and London: Routledge.

McNiff, S. (in press). Art is the evidence: Convincing public communication of art-based research and its outcomes. In R. W. Prior, M. Kossak, & T. A. Fisher (Eds.), Applied arts and health, education and community: Building bridges. Bristol, UK: Intellect and Chicago, IL: Univ. of Chicago Press.

McNiff, S. (2018, September). The common pulse of artistic expression and its infinite uniqueness. Creative Arts in Education and Therapy: Eastern and Western Perspectives. http://caet.inspirees.com/the-common-pulse-of-artistic-expression-its-infinite-uniqueness/

McNiff, S. (2021). Revisioning art and nature: Toward a depth psychology of creation. Ecopoiesis: Eco-Human Theory and Practice, (2), 1. https://en.ecopoiesis.ru/articles/article_post/mcniff-shaun-revisioning-art-and-nature-toward-a-depth-psychology-of-creation