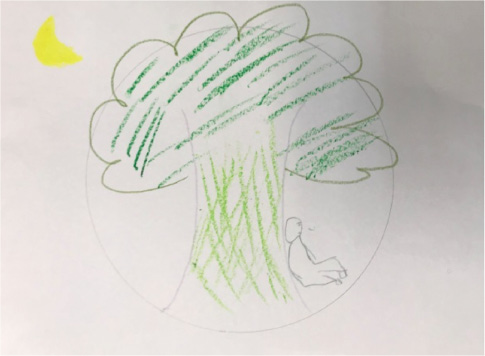

FIGURE 1 | Drawing in the first session.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2020) 6(2):127–140 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2020/6/24 |

Making Meaning Out of Intersectionality Through Expressive Arts Therapy: A Case Study

透過表達藝術治療從多元交織身份中建構意義:個案研究

International Expressive Arts Therapy Association, Hong Kong, China

Abstract

This paper illustrates how Expressive Arts therapy within a depth psychotherapy perspective helps one to face a heightened awareness of the four existential givens of life: death, isolation, freedom, and meaninglessness. The case of a mainland Chinese gay man, recently diagnosed with HIV, demonstrates how his intersectional identities come into play throughout the therapeutic process of meaning-making. Guided meditation and relaxation through listening to music, drawing, improvisation using the voice and the body, psychodrama techniques, story writing and Chinese calligraphy, which combines writing and drawing, all highlight the role of intermodal arts in igniting and deepening the process.

Keywords: intersectionality, existential, Expressive Arts therapy, meaning-making, Chinese

摘要

本文章說明表達藝術治療在深度心理治療的角度下如何幫助個案面對獲提高覺察的人生四大終極關懷 – 死亡、孤立、自由及無意義。一位新確診感染愛滋病病毒的中國內地的男同志個案將展示多元交織身份在意義建構的治療過程中如何發揮作用。聆聽音樂下導引冥想及放鬆、繪畫、聲線及身體的即興、心理劇技巧、故事創作及結合寫作和繪畫的中國書法突顯跨藝術媒介如何點燃和深化過程。

關鍵字:多元交織性,存在主義,表達藝術治療,意義建構,華人

Introduction

A biopsychosocial model is commonly used to understand how factors concerning various aspects in life bring forth a sense of well-being in a client and how these factors can possibly make a change (Zuckerman, 2010). This model matches the goals of depth psychotherapy which are “to coax gently out of the darkness those secrets that contain the key to understanding the individual’s suffering and … to liberate those possibilities for being that have been hostage by that suffering” (Craig, 2019, p. 134). The depth psychotherapy perspective includes, but is not limited to, psychodynamics and existential therapy (Craig, 2019). While the psychodynamic perspective might tap into past experience (Austin, 2002), the existential perspective brings the past to the here-and-now (Moon, 2009), and looks forward to authentic experiences that are yet to come (Corey, 2013).

Identities of an individual contribute various biological, psychological, and social factors within the biopsychosocial model and how these identities interact with each other should be examined carefully. For lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGBT) individuals, the identity formation process adds an additional layer to consider (Cass, 1984). Therapists, however, need to be mindful of any presumption of the dominant influence of a particular identity as it may not be the case for what is actually being experienced by the client (Huang & Fang, 2018). The “intersectional identities do not necessarily engender inner tensions and struggle but can become a source of strength and community connection” (Huang & Fang, 2018, p. 10).

Expressive Arts therapy as a holistic approach has been found to be instrumental in creating a “decentering” experience (Knill, 2005, p. 83) where clients are brought from the habitual world experience to an alternative world experience, offering “unforeseeable and unpredictable options” (p. 88). Being stuck in life is known as a “lack of play range” (p. 78) and the decentering experience can widen the play range. Decentering, which is analogous to the psychodynamic concept of transitional experience, through arts, play, and ritual allows the emergence of new meanings in symbolic or metaphorical form (Levine, 2005). Decentering through arts undergoes a subsequent “aesthetic analysis” (Knill, 2005, p. 150), which is the reflection on the process, the creative work, physical and psychological experiences, and the significance of the art-making. Each session is concluded by “harvesting” (p. 156), which refers to the clients’ reflection upon the issues they face in their lives, proactively seeking insights and solutions (Knill, 2005). By giving existential suffering a meaning, it can then be acknowledged (Levine, 2005; Kwong, Ho, & Huang, 2019).

This paper illustrates how intersectional identities can be explored when assessing a client who has just been diagnosed with HIV so that the client can come to terms with and make meaning of the illness as well as his life. Embracing opposites becomes prominent during this therapeutic process. This is important in in-depth psychotherapy, particularly for Chinese culture which stresses the importance of a correspondence and balance between yin and yang (Zhang, 2019).

Case example

Wu (pseudonym), a male in his 40s, had just been diagnosed with HIV before being referred for individual Expressive Arts therapy by a public HIV clinic in the non-governmental organization in which I was working. Born and raised in mainland China, Wu had obtained his Bachelor’s degree in the United States and had been working for an international firm in Hong Kong for several years.

People living with HIV (PLHIV) experience existential conflicts that are experienced by all humans but are particularly applicable to PLHIV. As being diagnosed with HIV is a significant life event, it can generate an anxiety that reflects a profound perception of threat to an individual’s existence (Yalom, 1980). Such conflicts may arise from a heightened awareness of death, avoidance of responsibility for choices, interpersonal isolation, and the meaninglessness of life (Farber, 2009). The exploration of such existential givens is particularly relevant to Chinese people as “there is a natural convergence between existential psychology and traditional Chinese thought” (Thrash et al., 2019, p. 100). I will illustrate how various existential themes were revealed and how identities came into play over the course of therapy where the arts played a significant role. Table 1 gives a summary.

TABLE 1 | Existential Themes, Identities Coming Into Play, and Art Modalities Used in Each Session

| Session | Existential theme | Identity comes into play | Art modality |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Isolation | PLHIV | Drawing |

| 2 | Isolation | Homosexual, graduate from a university in the United States | Story-writing and singing |

| 3 | Isolation | Homosexual, Chinese, son, elder brother | Collage, vocal improvisation, and playing with a singing bowl |

| 4 | Isolation, death | PLHIV, single, Chinese, expat in Hong Kong, Client | Co-drawing |

| 5 | Death, freedom | Chinese, single, son, grandson | Drama (empty chair) |

| 6 | Freedom | PLHIV, son | Body sculpture and movement |

| 7 | Freedom | All | Drawing |

| 8 | Meaninglessness | All | Drawing and Chinese calligraphy |

Stage 1: Exploration of Isolation

In the first session, I felt that Wu was a very polite gentleman. When I tried to give him my business card, it got stuck in the cardholder. He asked me to relax. I then asked him to clarify his expectation of the therapy and he believed that Expressive Arts therapy could help him express his emotions. According to his self-rated scores on scales for depression and anxiety, both were very low. I was conscious of the possibility that he experienced a numbing response as described by Farber (2009), where PLHIV might be emotionally numb so as “to buffer the emotional impact of anticipated death and loss” (p. 339). One goal of the therapy is to facilitate the awareness and expression of all sorts of suppressed emotions in order to live an authentic and meaningful life.

As Wu realized that meditating using a mobile app had recently helped him relax, I suggested doing this as an opening ritual in every session. I asked for his consent to audiotape the session and take pictures of his artwork for the purpose of clinical supervision but it was absolutely fine not to consent. He was unwilling to be audiotaped but taking pictures of his artwork was fine. I added that he could let me know later if he felt more comfortable being recorded. He felt more at ease after the guided meditation and subsequently I asked him to draw on a piece of A4 size paper with a pre-drawn circle, again he gave me a hand when I got stuck ripping a piece of paper from a pad. I was conscious of the tendency that he was more used to a caretaker role.

He began by drawing a thick tree trunk using a purple colored pencil (Figure 1), followed by drawing a green tree crown and a gray man sitting by the tree. He also added different shades of green representing leaves and finally a yellow half-moon. During the aesthetic analysis phase, he described the colors, shapes, and objects in the drawing and his intention to use gray to draw the human figure as it appeared to be not too vivid. He felt free and perceived that the human figure had a sense of security.

FIGURE 1 | Drawing in the first session.

Through dialoguing “with” the image, a method developed by McNiff (1992) to approach the image as a person before reducing it to an interpretation too soon, rather than talking “about” the image, Wu carried out a two-way conversation with the human figure. The human figure had started a new life and asked him to cheer up. The process naturally moved to the harvesting phase, during which the work of the image is understood in terms of the current life problem that has initially been brought into therapy (Levine, 2019). This can be understood as bringing unconscious material to conscious awareness through the art-making process, also signifying psychic growth from a psychoanalytic perspective (Levine, 2005). Wu realized that he was lonely but at the same time he felt support from within. He shared with me that he had joined a chat group for mainland Chinese with others diagnosed with HIV and this served to support him too. His identity as a PLHIV became a focus of the discussion. Like many other PLHIV, Wu faced an existential isolation as “[they] alone bear the burden of directly experiencing the physical and emotional effects of the illness” (Farber, 2009, p. 341). Helping Wu to build more relational resources and capacity to be alone became our therapeutic goal and he also agreed to explore his emotions further, primarily his loneliness.

In the second session, after the opening ritual of guided meditation, Wu told me that he had seen the musical La Cage aux Folles over the weekend. The musical told a story about a gay couple who had an adopted son. He was so struck by the authenticity of the main character Zaza who was just being himself and leading the entire audience to shout a Cantonese slogan meaning “if all of us are not straight, the world will be better”. I asked him how he viewed his LGBT identity, his response was that there was no problem at all, and discrimination is not allowed in his workplace such that he felt at ease even though he had not “come out” to his colleagues. However, he realized that despite being approached through a dating app, he was not interested in dating, pointing to a conflict in his belief system and his readiness to act. LGBT identity and HIV status are both minority identities, and Wu found a song to represent his minority identity, selecting Me (我), which is sung by an openly gay singer, Lesley Cheung. We listened to the song together and he said Zaza was very brave and many people out there had to experience a process of identity confusion.

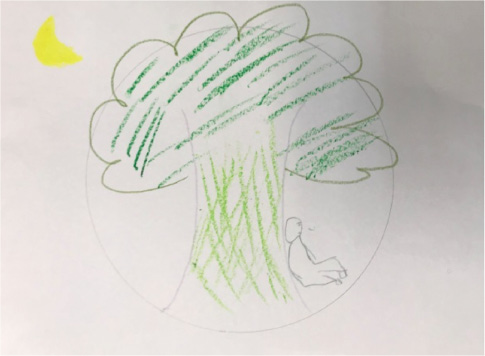

Trying to move Wu one step forward, I asked him to help Zaza create a story which illustrated how Zaza had overcome his identity confusion and became the one who could be so authentic. As shown in Figure 2, he said the turning point for Zaza was when he went to university where people were open-minded and understood each other so that he did not feel alone. This corresponds to the stage of Identity Tolerance in Cass’s theory of homosexual identity development (Cass, 1984), preceding the stage of accepting oneself as being homosexual. The use of arts and metaphor gave him a decentering experience and a safe and reflective distance to explore his identity issues so as to open gateways to surprising solutions (Knill, 2005). He naturally harvests the materials revealed by talking about his own story: When he was studying at the university, a male senior wrote him a love poem. It was, however, not until he had graduated from the university that he realized he was gay.

FIGURE 2 | Story-writing in the second session.

Such a process of affirming his LGBT identity can be transferred to the process of affirming his HIV status. The insight he gained in this session was that he could increase his own self-confidence as well as and gain acceptance from others by sharing this story. We sang the song Me as a closing ritual and he thanked me sincerely. Originally, we scheduled to meet two weeks later but he said he preferred meeting me the following week. This can signify his increased trust towards me as well as the willingness to play his part in the therapy.

He told me about his plan to go back to Shenzhen for the Chinese New Year holidays at the beginning of the third session. He said he would play mahjong with his father, mother and younger sister. His identities of being a Chinese, a son and an elder brother entered the scene. Through collage, we worked on identifying the different parts of his identity. He cut out pictures from magazines and put them together to form an art piece. He cut out the word ‘marriage’ (結婚) in both Chinese and English, an old man sitting in front of some flowers, and a red rose (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3 | Collage in the third session.

When describing his collage, he revealed that all the mainland Chinese PLHIV in the chat group had been talking about how to face their relatives when being asked about marriage during the Chinese New Year. He noticed his inner conflicts about choosing between a mainstream path or a difficult path which might make him die alone. I questioned him about what marriage really meant to him and he said mutual trust was what he valued. My follow-up question was whether a person who is straight would also be lonely and he said yes, realizing that being lonely was not restricted to gay people. He claimed that straight guys have more choices though. I again challenged his thought by asking one more question, “Would people cherish the relationships more if choices are limited?” He nodded.

I suggested using vocal improvisation to explore his feelings (Austin, 2008). Different chords within the C major scale were played and he picked the A minor chord to start with. An “intermodal transfer” (Knill, 2005, p. 125), which involves the shift from one art modality to another, took place naturally here as he had the image of a man looking upon the moon in the snow, feeling lonely but peaceful. The image gradually transformed into a guy walking slowly amid the desert under the starry sky which was leading his way. The sky in the Chinese culture is seen to have the power to determine the fate of humans but also affords blessings (Chan, 2019). In this case, the client gained some strengths from the sky. I used the C major chord to do a vocal improvisation with him as a closing ritual and he felt more relaxed and relieved. Before he left, he struck my singing bowl a few times, internalizing a peaceful image of a Chinese temple. According to Cowan (2019), existential loneliness is a transient condition in life whereas existential aloneness is a constant. Wu appeared to have more capacity to live with his aloneness. Starting from this session, facets of Chinese culture began to emerge.

Stage 2: Exploration of death

The fourth session took place after the Chinese New Year. Wu felt peaceful spending the time with his family and he slept well there. He had not managed to sleep well since returning to Hong Kong, but he was glad that he had a good relationship with his new boss. The relationship with his boss, quality time spent with his family, and practice in yoga, jogging and hiking seemingly helped his loneliness to subside. He also realized a source of support from a friend whom he had known for over two years.

I passed him a singing bowl for improvisation as a decentering experience. It was the first time he allowed me to audiotape the session. He created some very intense rhythms and associated the music with his stress at work. I questioned whether the music could be related to his anxiety when he could not fall asleep. He explained that he had become worried about the side effects of the HIV medication as these had been discussed on the mainland PLHIV chat group. This fear for his physical health was triggered by the group conversation and is also identified in his existential psychology where fear of existential death is heightened by the awareness of a potential pending death as a result of HIV (Farber, 2009). Cognitively, he understood that he was fortunate as he could receive first-tier HIV medication in Hong Kong whereas PLHIV in the mainland China could not and had to face stronger discrimination against their sexual orientation and HIV status. Besides, he was thankful for his high socioeconomic status and richer life experience so that he had greater capacity to live with HIV, unlike those teenagers whose life would be over according to him. I affirmed his courage but at the same time pointed out that being infected with HIV at a young age can still have a meaningful future. He agreed.

As both homosexual identity and HIV status are considered as a minority identity, people in both groups are stigmatized. Developing a sense of universality would be helpful in moving from the stage of Identity Tolerance to Identity Acceptance (Cass, 1984). I asked him whether he noticed any commonality among the people in the chat group, he said all of them were lonely. Although it gave him a sense of universality, I tried to expand his perspective by asking him what made him think like this. He said all of them did not have a romantic partner and that was why they had time to chat in the group. I challenged him by asking him if anyone in the group was partnered. Interestingly, he said yes, and many were serodiscordant couples, meaning that one partner is HIV-positive, and one is not. I shifted his focus to see hope as there are people without HIV who are willing to engage in a long-term relationship with PLHIV. He remembered that trust is the key for successful relationships, regardless of being HIV positive or not. But still, he believed that loneliness remains if one is not partnered.

Wu and I then co-created a drawing (Figure 4). He made a few additions, including a line which looks like a cliff, a yellow man without a face, and a bridge. I built on what he had drawn and noticed that he did not react to my additions. What I felt was that the art-making was not a two-way interaction. During harvesting, he revealed that he had been alone for most of his life. He felt the support from the backpack which I drew on the yellow man. He added that he actually felt secure when we drew together instead of drawing alone. The symbolic meaning of giving him support from the therapist can also be a relational resource for him to alleviate his existential isolation. The identity of a client who seeks help can also be empowering as he did not have to take up the caretaker role all the time.

FIGURE 4 | Drawing in the fourth session.

The exploration of death went on in the fifth session. The first thing he shared with me was related to his family. It took him quite a while to tell the details though. His grandmother who moved back from Shenzhen to their hometown in another province in China several years before had recently become sick. She was currently being taken care of by Wu’s uncle and younger sister, but he thought he also had to go visit her. He noticed that death was so close to him. Such an existential given became prominent in this session, perhaps he was ready for the exploration. I asked him to pick something in the room to represent death and he pointed to the black ceiling. “The collapse of the sky” is a common Chinese saying used by PLHIV who have just been diagnosed to describe how they feel. Being told to adjust his position to illustrate how close he was to death, he remained seated on the sofa. I introduced a focusing technique, which is a process of attending to the bodily-felt sense of an issue, situation, or experience, and connecting the body, mind, and spirit (Rappaport, 2009). Bodily-felt sense refers to “a direct bodily awareness and experience of our inner state” (p. 28). Wu described seeing light out of the darkness. There was a long silence before he said that death could be a good solution. He went on to explain that the reason he chose to sit on the sofa was that he could still feel comfortable even when his life was being taken away. I asked if this comfortable feeling could be found somewhere else in his life and he said it was the time, in his 20s, when he did not have much burden. His mother had been diagnosed with cancer two years ago. Although the tumor had been under control, he felt it was like a time bomb. Being a man, however, made it more difficult to show his vulnerability at home. This echoed with my impression in the first session that he had always been a caretaker who can only be seen as being tough.

When he started to come to terms with the unknown about death and finiteness in life, the anxiety began to be alleviated. The focus of exploration had shifted from death to freedom in the middle of this session.

Stage 3: Exploration of freedom

In the second half of the fifth session, I suggested that he express his vulnerability by using a character to represent someone who is weak, he thought of a child at the age of five or six. I used Moreno’s psychodrama technique called “empty chair” (Garcia & Buchanan, 2009), which uses a chair placed in front of the client to symbolize another person, part of the self, or a meaningful object (Austin, 2008). I guided him to talk to the little child to process past incidents (Leijssen, 2006). He said to the child, “Go play around. No one will scold you. You grandmother won’t scold you. It’s OK if your uncle dislikes you. Remember it’s not your fault for your dad’s bad temper.” He reflected on his childhood and described himself as very disciplined. He would be considered as a bad kid for running here and there. His cousin had been smart and Wu’s family members did not see Wu as a smart kid. I was concerned about how Wu saw himself and he said he used to have the same ideas but no longer believed that after so many years.

Playfulness was probably something that was missing during his childhood and through expanding the range of play, PLHIV’s creativity and cognitive flexibility can be enhanced (Zabelina & Robinson, 2010). I suggested playing a game together and he wanted me to suggest one. We did a finger fight and he found it very fun, although he was worried about hurting me. I told him that it did not hurt. A play-oriented experiential time can be good enough for a transformation to take place and this truly interactive experience can be reparative, giving a sense of security both internally and externally.

He shared good news to me at the beginning of the sixth session. His viral load had reached an undetectable level whereas his CD4 count rose from 300 to 400, both signifying an improvement in his physical health. Besides, his grandmother’s health status had become stable. What was important to him then was earning more money so as to enhance his financial ability to face any challenge in the future. I asked him what kind of challenge he referred to and he said he was thinking about physical health. Although his current health status had stabilized, he still had the worry of eventually getting worse and was unable to see any possibilities in his future. Exploration on the notion of freedom seemed to help him reflect on the challenges of living with the unknown and opened him up to possibility of further growth. We took turns to pose so as to react to each other’s posture. He took some time to react initially but gradually became more spontaneous. During the aesthetic analysis, he noticed that he needed to understand what I was expressing, and this was hard for him. I questioned him what if he did not need to understand what I meant and just reacted to what he thought, he said in that case he could not do it. He harvested what had been revealed by noticing that it became hard for him to build a sustainable relationship with others as he had his own habits. He also related this to his freedom to imagine and create because his parents had disallowed him to choose. He had been forced to learn martial arts during his childhood and if he did not attend the lesson, he would be scolded by his father. He had wanted to become an artist. PLHIV may have anxiety about taking responsibility for decision-making and its consequences (Farber, 2009), exploring the possibilities even when some external circumstances are unalterable can help alleviate such anxiety. I guided him to move his body together with me while I played some soft music. He gradually became much freer to improvise and felt really relaxed. I asked him what made him relaxed and he said it was my guidance. I asked if there was anything else and his answer was the music. He did not recognize his spontaneity and I pointed out that it could have played a significant role. He nodded but I knew that he might need to experience it more deeply and internalize it.

The seventh session had been a month since the previous session because his work had kept him busy. His first update was about knowing a new guy in the mainland Chinese PLHIV chat group and he had a crush on this person who was a reporter. This guy had been diagnosed with HIV for five years and started HIV treatment in mainland China. Although he came to Hong Kong three years before, he had not been aware that he could actually get first-tier medication care at a low cost just like other Hong Kong PLHIV. Wu told him that he could get better medication in Hong Kong and brought him to see the doctor. Wu’s feeling of being a mentor to give others information and care empowered him as he felt like he had already passed through the toughest times.

According to Bugental (1965) one must first face aloneness in order to engage deeply and meaningfully in relationships. The balanced condition is to be a part of and apart from others at the same time. I suggested him to use his non-dominant hand to draw the person he liked with only one line, trying to break his usual pattern of planning and allow authentic feelings and thoughts to be revealed. I then asked him to also draw himself in the same way. I suggested that he add something on the two drawings. During the aesthetic analysis, he described the guy he liked as a pure person who would fight for justice. The hair in an upright position he had drawn symbolized such passion. On the other hand, Wu saw himself as a calm person. I asked him to give a rating on his peacefulness and he said it was seven to eight out of 10 as compared to four when he first came to see me. He then found similarities and differences between the two. I asked him to connect the two drawings by adding anything he wanted. He put the two pictures side by side and added a symmetrical roof above the two of them. Through his art-making process he had been able to express his dreams and hopes for a secure, equal relationship, and a family. He felt that his feeling of loneliness had gone. Existentially, he had become able to live with his aloneness but also to connect with others. This is in parallel with the integration of his identities as a Chinese person who is more relational and his more American identification, with a more individualistic approach to life (Zhang, 2019). In this session, no specific identity dominated the therapeutic process, and it could be explained by the last stage of identity formation which is the synthesis of all identities (Cass, 1984).

Stage 4: Meaninglessness

We agreed to terminate our therapy at the eighth session. He told me that he and the person he liked were still in the stage of exploration. Reviewing the changes he had experienced, he noticed that he did not feel fear anymore and could live with his aloneness. The existential givens of Isolation, Death, and Freedom had been well explored and the Meaninglessness had to be finally addressed by consolidating the meaning of his illness and his life.

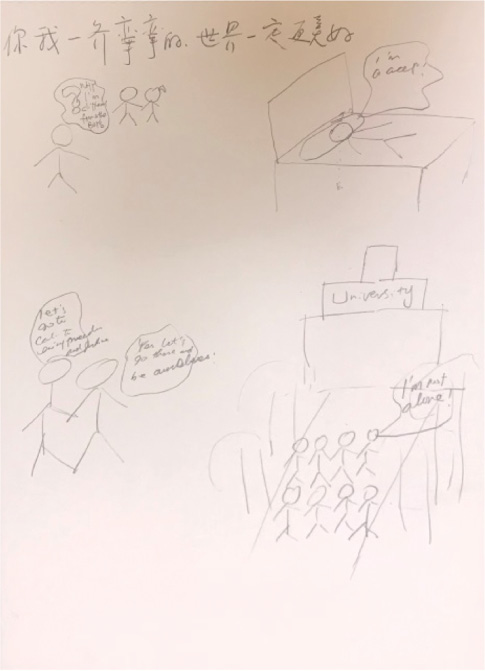

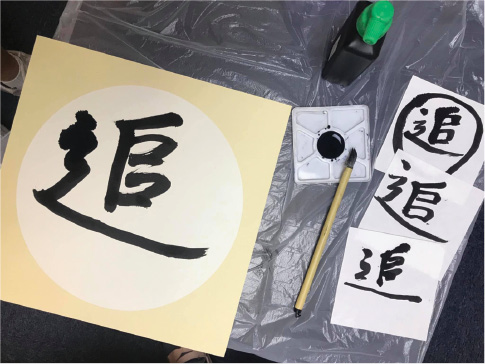

To envision his future, visual art was chosen. He used pink to symbolize an LGBT individual who could share his own journey of living with HIV on the stage. This corresponded to an advanced stage of the LGBT identity formation model called Identity Pride (Cass, 1984). He had the courage to face his own minority identities which are heavily stigmatized. To make meanings and consolidate what had experienced in the whole journey of therapy, words were the chosen modality as they could help “images, acts, movements, rhythm or sounds to find a cognitive sense” (Knill, 2005, p. 126). I found Chinese calligraphy particularly meaningful as his identity as a Chinese person had always entered the therapeutic process. He picked the Chinese character ‘追’, which means to chase or pursue. It is actually the title of a song sung by Leslie Cheung, whose song we had listened to in the second session. Chinese characters are pictorial, and he “drew” the same word a few times (Figure 5). Encircling the character made him feel constrained. Removing the boundary but drawing in a rigid form was still not good enough. Finally, drawing freely made him feel better and so he repeated the drawing in the same way on a bigger piece of paper with a body movement that appeared to be very spontaneous and free. The Chinese character looked like a ship to him (and to me). It is moving forward, and he was sailing on it.

FIGURE 5 | Chinese calligraphy in the last session.

Conclusion of treatment

As illustrated in this brief therapeutic process, various existential themes became the center of the therapy alongside the exploration of various identities. Within six months, the client was able to face the unknown and finiteness in life, to be both a part of the community and apart from others, to resume his responsibility of living his own life, and to make existential meanings so as to move on with his life. Arts as a non-verbal means of expression played a significant role in gaining insights and eliciting the transformation.

Concluding remarks

Minority identities are sometimes not the major factors influencing the life of a client. It can be the interaction between a minority identity with another identity that should be taken into consideration. PLHIV is an identity that is closely related to the homosexual identity and both identities are heavily stigmatized in Chinese culture (Huang & Fang, 2019; Kwong, Ho, & Huang 2019). In a Chinese cultural context, issues arising from the homosexual identity can become complicated with the family and societal expectation of continuing the blood line (Huang & Fang, 2019). In addition, a burden on Chinese men can be heavy as they are not allowed to show their vulnerability socially. Because of such identities, the relationships with family and society apparently play a more crucial role in the social factors within the biopsychosocial model. Expressing and embracing feelings which include loneliness and fear can help one live authentically and meaningfully. Arts can play an important role in embracing the opposites and making a balance – the collectivism in Chinese culture and individualism in the West where the client was educated; the unconscious materials being brought to the conscious; and both verbal and non-verbal means of expression. This is the Taoist concept of “yin and yang” (Zhang, 2019, p. 340). The sides that are less seen or less accepted are transformed into strengths and resources. Through engagement in the art-making process, existential meanings can be made.

About the Author

Kwong Man Kit, Aleck, is an expressive arts therapist, registered with the Australian, New Zealand and Asian Creative Arts Therapies Association. He graduated with distinction from the Master of Expressive Arts Therapy program at the University of Hong Kong and was awarded the Madam Lo Ng Kiu Ying Anita Memorial Prize. He is also an Austin Vocal Psychotherapist (AVPT). He mainly works with children with special educational needs, adolescents, ethnic minorities, the mentally ill, the developmentally delayed, the bereaved, LGBT individuals, PLHIV, and people with dementia. Building on his former work experience in an investment bank and other financial institutions, he also conducts stress management and team building programs for corporations. He has been a guest speaker for undergraduate courses at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, the Education University of Hong Kong, the Open University of Hong Kong, and the Caritas Institute of Higher Education. He has also been a guest speaker for Master’s Programs at the University of Hong Kong. He was a presenter at the 11th, 12th, and 13th International Expressive Arts Therapy Association (IEATA) Conference and is now a board member of IEATA. He was also a presenter at the 2018 International Conference on Existential-Humanistic Psychology.

References

Austin, D. (2002). The voice of trauma: A wounded healer’s perspective. In J. P. Sutton (Ed.), Music, music therapy and trauma: International perspectives (pp. 231–259). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Austin, D. (2008). The theory and practice of vocal psychotherapy: Songs of the self. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Bugental, J. F. T. (1965). The search for authenticity: An existential-analytic approach to psychotherapy. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Cass, V. C. (1984). Homosexual identity formation: Testing a theoretical model. The Journal of Sex Research, 20(2), 143–167.

Chan, A. (2019). In harmony with the sky: Implications for existential psychology. In L. Hoffman, M. Yang, F. J. Kaklauskas, A. Chan, & M. Mansilla (Eds.), Existential psychology East–West (Vol. 1 – Revised & expanded ed., pp. 311–26). Colorado Springs, CO: University Professors Press.

Corey, G. (2013). Theory and practice of counselling and psychotherapy (9th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Cowan, E. G., Jr. (2019). On existential aloneness: The earthly pilgrimage. In L. Hoffman, M. Yang, F. J. Kaklauskas, A. Chan, & M. Mansilla (Eds.), Existential psychology East–West (Vol. 1 – Revised & expanded ed., pp. 301–310). Colorado Springs, CO: University Professors Press.

Craig, E. (2019). Tao, daesin, and psyche: Shared grounds for depth psychotherapy. In L. Hoffman, M. Yang, F. J. Kaklauskas, A. Chan, & M. Mansilla (Eds.), Existential psychology East–West (Vol. 1 – Revised & expanded ed., pp. 133–166). Colorado Springs, CO: University Professors Press.

Farber, E. W. (2009). Existentially informed HIV-related psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 46(3), 336–349.

Garcia, A., & Buchanan, D. R. (2009). Psychodrama. In D. R. Johnson & R. Emunah (Eds.), Current approaches in drama therapy (2nd ed., pp. 393–423). Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas.

Huang, Y.-T., & Fang, L. (2018). “Fewer but not weaker”: Understanding the intersectional identities among Chinese immigrant young gay men in Toronto. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 89(1), 27–39.

Knill, P. J. (2005). Foundations for a theory of practice. In P. J. Knill, E. G. Levine, & S. K. Levine (Eds.). Principles and practice of expressive arts therapy: Towards a therapeutic aesthetics (pp. 75–170). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Kwong, M.-K., Ho, R. T.-H., & Huang, Y.-T. (2019). A creative pathway to a meaningful life: An existential expressive arts group therapy for people living with HIV in Hong Kong. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 63, 9–17.

Leijssen, M. (2006). Validation of the body in psychotherapy. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 46(2), 126–146.

Levine, S. K. (2005). The philosophy of expressive arts therapy: poiesis as a response to the world. In P. J. Knill, E. G. Levine, & S. K. Levine (Eds.), Principles and practice of expressive arts therapy: Towards a therapeutic aesthetics (pp. 15–74). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Levine, S. K. (2019). Philosophy of expressive arts therapy: Poiesis and the therapeutic imagination. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

McNiff, S. (1992). Art as medicine: Creating a therapy of the imagination. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Moon, B. L. (2009). Existential art therapy: The canvas mirror (3rd ed.). Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas.

Rappaport, L. (2009). Focusing-oriented art therapy: Accessing the body’s wisdom and creative intelligence. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Thrash, J. C., F. J. Kaklauskas, M. M. Dow, E. Saxon, A. Chan, M. Yang, & L. Hoffman. (2019). Existential-humanistic psychology dialogues in China: Beginning the conversation. In L. Hoffman, M. Yang, F. J. Kaklauskas, A. Chan, & M. Mansilla (Eds.), Existential psychology East–West (Vol. 1 – Revised & expanded ed., pp. 97–110. Colorado Springs, CO: University Professors Press.

Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Zabelina, D. L., & Robinson, M. D. (2010). Creativity as flexible cognitive control. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 4(3), 136–143.

Zhang, B. (2019). Funerary rituals in China, Confucianism, and the existential issues of death and meaning. In L. Hoffman, M. Yang, F. J. Kaklauskas, A. Chan, & M. Mansilla (Eds.), Existential psychology East–West (Vol. 1 – Revised & expanded ed., pp. 337–346). Colorado Springs, CO: University Professors Press.

Zuckerman, E. L. (2010). The clinician’s thesaurus: The guide to conducting interviews and writing psychological reports (7th ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.