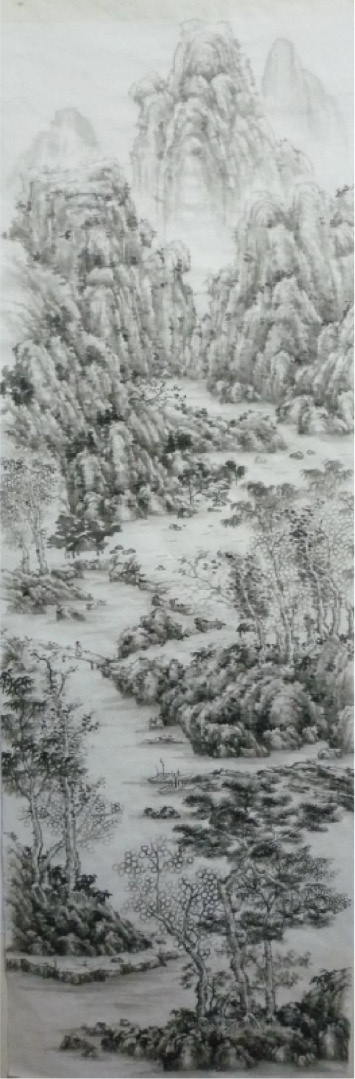

FIGURE 1 | Sketch by W.Y. Leung

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2020) 6(2):209–220 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2020/6/23 |

Two Sides of Landscape in Ink-wash Painting: Chinese Landscape Painting in Expressive Arts Practice

水墨的兩面風景:從表達藝術治療理解中國山水畫創作

Kunst EXA Training and Consulting, Hong Kong, China

Abstract

Chinese landscape painting does not pursue the accuracy of the subject’s outer appearance, instead, it captures the energy, life force, and spirit beyond. The various styles of calligraphic lines are expressive and become a language to convey one’s belief. The interwoven relationship between Chinese landscape painting and painter exhibits its compatibility with the practice of expressive art in some aspects. The high skill/high sensitivity required for Chinese landscape painting evokes a good awareness of oneself, it exercises the senses and opens up the imagination. The expressive calligraphic brushstrokes create a delicate world that echoes the inner state of the painter that will lead the way and reveal itself. Being immersed in the “landscape” in the painting enables people to remove themselves from daily life and channel themselves into another world. The sense of being insignificant in the face of the vast landscape teaches the viewer to surrender to what may come and to uncertainty.

Keywords: Chinese landscape painting, Expressive arts, Taoism, high sensitivity

摘要

中國山水畫並非追求描繪景物外形上的相似,而是著重表達其蘊藏的能量、生命力及內在精神。千變萬化及靈活的筆觸線條甚具表達力,讓其成為語言述說自己的故事。與表達藝術治療一樣,中國山水畫裡的創品與畫者有著親密互動的關係。中國山水畫要求的高技術高敏感度能喚起畫者自身的覺察、提升感官敏感度和擴展想像力。具生命動感的書法線條能創造一個細緻的世界,由畫者的心驅使畫筆,以展現及回應畫者的內在狀態。當畫者/ 觀賞者攝於山水畫裡雄偉的「風景」時,這片刻能讓他們精神上離開日常的紛擾,並進入另外一個世界,於大自然中感應其自身的渺小亦讓人領悟出以更寬容的態度應對未知。

關鍵詞:中國山水畫,表達藝術,道,高敏感

The language of Chinese landscape painting

Chinese landscape painting, shan shui hua (山水畫, picture with mountain and water), is literally a painting of mountains and water, both of which are material and tangible features of nature. Chinese painting is closely related to the Zen Buddhist and Taoist ideals of total concentration in the act of the very moment, and harmony between man and nature (Shaw, 1988). It involves brush and ink on paper and uses disciplined brush skills that are required for calligraphy to animate its subjects. A few strong black lines, ink wash, and dotted brushstrokes can suggest a mountain with hard rocks. The life, spirit, and mind of the painter are revealed in a symbolic way on paper, with laissez-faire and vigorous round brushstrokes showing different temperaments. The various styles of calligraphic lines make themselves expressive and become a language to convey one’s beliefs.

Some qualities of Chinese landscape painting correspond to Expressionism’s notable trait –expressing the meaning of emotional experience rather than physical reality. Chinese landscape painting depicts the outward appearance of nature but is equally concerned with the movements of the energies that infuse the natural world with life. The appearance of the painted object is authentically reflected in the true object, yet it does not pursue the accuracy of the subject’s outer appearance. It utilizes sophisticated painting techniques and the utmost exploitation of the materials, resulting in lifelike pictures with rich sensuous values. Chinese landscape painters express their inner understanding of the subject, aimed at revealing the energy, life force, and spirit beyond the subject rather than merely reproducing its dimensions and outlines (Xu & Wang, 2013).

The enchantment of Chinese landscape painting is in its poetic, symbolic, and spiritual nature. While the “landscape” is transformed and reproduced, the spirit and the land are then convincingly weaved together in the picture. It creates a meaningful perception of nature, which gives things that once were mere objects, the chance to become subjects with agency and power. The painting becomes expressive art which mirrors its inner sense and beyond, if art is not mere self-expression, something unknown in the inner senses is now revealed. Thus, things from nature acquire new meaning because they are no longer seen as inanimate objects lacking life, but as animistic and it follows the rule of Tao in the same way as living entities. Indeed, the landscape becomes a visible symbol of the all-embracing universe (Rowley, 1947).

Follow the Tao (way) in the landscape

One of Taoism’s most important concepts is wu-wei (無為), which means effortless action. Wu-wei is regarded as the way of “becoming a fully realized human being”. It requires letting go of striving for a goal and instead being very conscious of what is happening in every moment (Levine, 2019; Slingerland, 2007). It is believed that the universe has its own rules and everything unfolds by itself. In expressive arts, “poiesis” means making in general. It can refer to the particular mode of making in which something is made so that it can appear as made (Levine & Levine, 1999). That means it allows something to be manifested in front of people, disregarding what art form it is. It is also the act of responding to what is given, imagining its possibilities and reshaping it in accordance with what is emerging. In order to genuinely reflect the experience and feeling, it requires the attitude of “letting-be” so as to embrace what comes to us.

Levine stated:

it (the creative process) happens not in accordance with intellect and will but through the experience of surrender to a process which I can neither understand nor control in advance. Once the work arrives, then I need to exercise my knowledge and capacity in helping it to find its appropriate shape. …I must abandon my critical intention and become open or receptive to what is coming. (Knill, P.J., Levine, E.G., & Levine, S.K., 2005, p. 41)

The practice of poiesis shows us that whatever the initial idea, feeling, and sensation, the image has a mind of its own, taking us into new and unexpected paths. The role of the artist is to follow the image and enable them to emerge in their way, not to impose a pre-conceived plan. The artist would follow what is emerging, instead of dominating it and forcing it to go their way, to create room for something new to emerge, which is always a surprise for us.

Chinese landscape painting allows the mind (in ancient Chinese; mind = heart; or including the heart) to lead the brush. When the painter is sensitized and mindful, one stroke will come after another stroke on its own accord. The image which echoes the inner state of the painter will lead the way and reveal itself. Despite the requirement of a high degree of control in Chinese landscape painting, the painters always respond to what is given, and in this sense, they are free to make their worlds and themselves anew. The high discipline and structure of Chinese landscape painting make it hard to forgive any retouching on a single stroke which would induce inconsistencies in the ink densities and affect the image adversely. Brushstrokes cannot be erased or corrected once put on rice paper. It somehow impels people to be exceptionally mindful and even surrender to the “mistake” and to work with the “unexpected” brushstroke. Therefore, every stroke embodies the awareness and high energy of the painter, permeating the landscape with life (chi 氣).

Sublimation beauty of a landscape

Sublimation refers to the psychological processes of transformation, in which base and unimpressive experiences are converted into something noble and fine. Art can offer a platform that surveys the travail of our condition (Botton and Armstrong, 2016). Psychological suffering is intrinsic to the human condition. In expressive arts, it is a basic human need or drive to crystallize psychic material, so as to move towards optimal clarity and precision of feeling and thought. The task of therapy is not to eliminate suffering, but to give a voice to it, to find a form in which it can be expressed.

The high skill and high sensitivity required for Chinese landscape painting is a restriction on the use of this modality but enriches the expression with textures and sensuousness. The expressive calligraphic brushstrokes help create a delicate world to demonstrate temperament and contain a story. The layout of the painting displays how different objects relate and posits in the two-dimensional picture; the space is as important as the objects, which creates balance and harmony among things. Chinese landscape painting employs brushwork to evoke images and feelings; it shapes the landscape to create another “world” to convey life spirit and meaning. The characteristics of rocks and trees, felt by the painter and acted out through his calligraphic brushwork, are imbued with a heightened sense of life energy that goes beyond mere representation. It constructs an “effective reality” for the painter. The effective reality, meanwhile, arouses affective-sensory experience, which makes the painter stop and compels his attention to what is happening in the moment (Levine, 2012). Painting is no longer about the description of the visible world; it becomes a means of conveying the inner landscape of the painter’s heart and mind. Besides, the painter experiences himself as an active participant in the painting as well as their life.

“Language” of EXAT, in relation to Chinese landscape painting

Decentering in nature

Decentering is a path where an art-based understanding of the work of art and the process of shaping becomes the stepping-stone to a psychological conversation. It is a process about stepping into an alternative experience of worlding. It brings a different relationship to everyday life, through imagination contained in a symbol, we can find new understanding and meaning for that daily reality (Knill, Barba & Fuchs, 2004). According to the Principles and Practice of Expressive Arts Therapy:

by decentering, we name the move away from the narrow logic of thinking and acting that marks the helplessness around the dead-end situation in question. This is a move into the opening of surprising unpredictable unexpectedness, the experience within the logic of imagination. (Knill, Levine & Levine, 2005, p. 83)

With exploration in imagination, decentering opens options for new actions and thoughts, which contrasts with the situational restriction experienced by the seeker of help. It expands the perspective of the seeker of help and provides more alternatives. Finally, Expressive Arts therapists will close the decentering using a centering phase, bringing the harvest found in the decentering back into reality and with it, nurture the life of the seeker of help.

The vast landscape in Chinese painting represents the vastness of the universe. Chinese landscape painting is sublime in the magnificent and majestic sense, which depicts the great mountain chains, sheer cliffs, and precipitous rock faces. The human figure in the Chinese landscape painting is usually not the protagonist, and appears very tiny in size and resides indiscriminately in the midst of nature. It metaphorically exhibits who we are in the vast cosmos. These works make us aware of our insignificance, having a sense of how petty man’s issues are in comparison with the universe and the ways of eternity, leaving us with more breathing space to take in the intractable struggling (Botton and Armstrong, 2016). From here, ordinary irritations and worries are alleviated. With exploration in the mountains cape, Chinese landscape painting serves as an entry for decentering, providing access to another world. It helps to expand the perspective of painters and provides more alternatives, contrasting the situational restriction experienced by the painter. As a result, it becomes a reservoir of calm at the vortex of a world.

When staring at Chinese landscape paintings from a distance, it allows us to be absorbed in the scenery, and also project ourselves into the painting. The surrounding mountains give a vast containment for us as well as for our psychological suffering. Viewers are meant to identify with a human figure in the painting, allowing them to “walk through, ramble, or dwell” in the landscape. “Travelers” can make their way along the path, wandering from peak to vale and even sit in the pavilion to enjoy the view. The play of mountains and water absorbs viewers and allows them to become lost in it. It invites us to linger endlessly without coming to a terminus. Rather than try to redress the situation by solely insisting on putting ourselves at the center of the problem, Chinese landscape painting helps us to learn to apprehend and appreciate our essential nothingness (Botton and Armstrong, 2016).

When we work on a Chinese landscape painting, it usually does not refer directly to our relationships, or to the stresses and tribulations of our everyday lives. Instead, it enables painters to get access to a state of mind in which the painter would be acutely conscious of and fall into the vast stretch of time and space. The images draw us away from ourselves; we forget our immediate preoccupations as we give ourselves over to be assimilated into the landscape. It seems like the “liminal space” in expressive arts, which is a rite of passage that allows for considerable changes to be made. Artwork can compensate the inner fragilities of the viewer and we can get what we need in viewing the painting. We call a piece of work beautiful when it supplies the substances we are missing.

Chinese art materials: Water–ink–brush and body

Chinese landscape painting is about water, ink, and brush, and their encounter with rice paper. The restriction of the materials make room for higher attention to one’s self. Focusing on water and ink in the brush and their interaction with the paper, it cultivates mindful attention to the here and now experience and literally comes to our senses. For example, when we utilize round-stroke with saturated ink in the bag of the brush and put brush to paper, a rich and thick brushstroke appears. Being mindful is necessary for the painter to have a sense of the ratio between ink and water in the bag of the brush, so as to draw lines with different styles. Between, the resulting water–ink rendering gives a very strong visual impact. The variation in brushstroke tells us about the correlations among our sitting position, the extent of our strength, pacing, confidence, technical mastery, and spiritual energy. This is definitely an integrative body–mind–spirit work. The work itself encourages psychological conversation and enables us to step into an alternative experience of worlding. The high sensitivity cultivated gives the painter a different relationship to everyday life and inspires him to find new understanding and meaning for his daily reality. This sequence of shifts gives rise to “embodied experience”. “Embodied” means to feel one’s self through bodily felt responses in the moment. This allows for the possibility of constant change in response to connections made between the physical, emotional, and thinking processes (Knill et al., 2005).

Taking this perspective, it fulfills a movement-based approach in expressive arts, in which working with movement is to bring awareness and expression to the interplay between body, mind, feeling, and spirit to reveal the unknown parts of the self (Levine, 1999). The embodied experience exercises our senses and opens the imagination, enabling us to re-access a range of life-responses and reactivates feelings and images associated with life experiences. This contrasts with the situational restriction. Moreover, it expands the perspective of the painter and provides more alternatives.

While the challenges of mastering Chinese art materials gives an embodied experience and helps the painter to be more focused; however, it may restrict the painter from freely exploring with the materials. Low skill/ high sensitivity is an important concept in the Expressive Arts introduced by Paolo Knill (Knill et al., 2004), who said that art that can touch and move us is not always the product of the excellent skill, often what is most outstanding is a keen sensitivity to the material, time, and space of the art modality. The mastery of technique is not the primary purpose of the expressive arts. Chinese landscape painting, however, is definitely high skill/ high sensitivity. Chinese landscape painting requires years of training and experience in order to achieve technical competence. Undoubtedly, greater exploration and mastery of this modality can greatly enrich the painter’s understanding of the creative process, and can give him/her more ease and confidence in using the modality. It also attains aestheticism. In Chinese landscape painting, the high skill required includes high sensitivity to the materials, reenforcing people to be more mindful and conscious in the present moment. However, to a certain extent, it may hinder people from enjoying the freedom of expression that allows for individual experience and reflection to emerge.

Aesthetic language: My journey with Chinese landscape painting

I have studied Chinese landscape painting for over 10 years and learned how to paint by imitating the paintings from ancient Chinese painters. I have developed a sense of the ink and water in the bag of brush and can make thick and thin ink on the paintings as I wish and depict the objects in details. In the imitating process, I pay full attention and am totally absorbed in the painting as well as in the landscape. Sometimes when I felt stuck in life, doing a Chinese landscape painting has helped me to resolve the problem directly. It constructs a consoling space for me to retreat from the incomprehensible reality and enables me to take good care of myself. It enables me to be more revitalized to find an alternative path during my difficulties. Studying Chinese landscape painting has trained me to be a good observer, noticing the color, shape, ratio, the cause and effect that happen in nature and my surroundings. In Chinese landscape painting, landscapes are often painted from a viewpoint above the scene, so that many “areas” of the landscape can be seen at once. In large scenes or landscapes, the eye is meant to travel along a visual path from one area to another, which broadens the horizon of seeing.

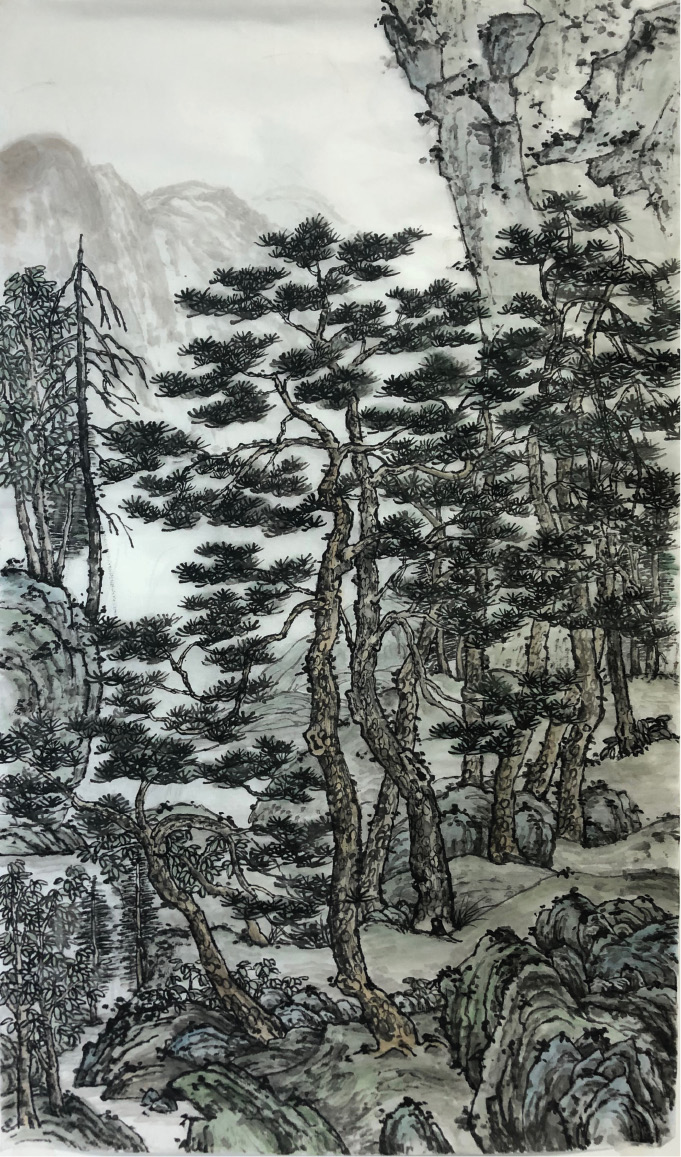

When I immerse myself in doing Chinese landscape painting, every leaf and texture of bark (Figure 1) strikes me and immerses me in the painting. My full presence enables me to offload the tedious and annoying routine of daily life. It creates an unlimited space for me to free myself from the limited physical space I live with every day. When I was mentally wandering in such an enormous space as in the painting shown in Figure 2, I realized human beings are negligible in the world. I felt relieved and had an ease of mind. Even though I do not go into the depths of the painting process, such realization is indeed healing and fosters in me the feeling of flexibility in the situation where I feel stuck.

FIGURE 1 | Sketch by W.Y. Leung

FIGURE 2 | Surrounding Mountain (環山圖) by W.Y. Leung

Chinese landscape painting, like Expressive Arts Therapy, adopts a movement-based approach. It helps me to shift my attention from my daily routine and dive into a devotional space. It induces affective sensory experiences and involves whole-body participation–sit upright, let your hands and shoulders relax, and with your feet on the ground stare at the paper softly. Once I start a work, I become conscious of every stroke and it comes to me one after another, which eventually strives to work for its completion. The completed work will bring a sense of amazement to my heart.

Doing Chinese landscape painting involves many steps. I normally take a master painting as a blueprint and then start imitating it. While my mind follows the here and now experience which keeps changing in every moment, the final painting will no longer be the same as the blueprint. The object at is in the bottom of the painting is be the first to be painted. Then, the object next to the former objects is the second to be painted and this develops a relationship and interaction with the surroundings. The object comes gradually. Artists leave at least one-third of a painting as “space” in Chinese landscape painting, this area is called “space for breathing”. It serves as ventilation in the “scenery” and vividly brings life to the painting. It is then followed by applying thick and thin ink, layer by layer to do shading and texture of objects. The painting then becomes tangible and full of sensuous stimulation. Whether you are painter or viewer, it is tempting to project yourself into Chinese landscape painting and then find yourself embraced by the mountains in a vast landscape, which touches your inner heart and induces an aesthetic response (Figure 2).

In ancient times, landscape painting had evolved into a tool that was used to express the longing of the literati to escape their quotidian world to commune with nature. The concept of withdrawal into the natural world even became a major thematic focus of poets and painters. Such images might also convey their social, philosophical, and political messages. Faced with the failure and helplessness towards the outer world, people sought permanence within the natural world, retreating into the mountains to find a sanctuary from the chaos.

These sentences are politically sensitive and can put the author and her affiliated organization, as well as the journal on risk. We suggest to rephrase them and eliminate those sensitive words in this special period of time. At this moment, doing Chinese landscape painting serves as a wayout, allowing me to temporarily “decenter” from the emotional turbulence. Figure 3 is a painting I made during that time. The tension between staying focused on the painting and being distracted by the reality of what was going on around me was a struggle. A little fidgeting would be reflected in a brushstroke and make it harder to draw a line with ink. Through the painting, I tried to pursue a tranquil state of mind in the face of what I have been exposed to, and to find shelter in the midst of the unrest. I let my eyes wander under the shadow of trees and be swallowed up by the forest, immersing myself and becoming part of the landscape. In the face of the universe, it feels like time becomes eternal and the world will go on in my absence. In the huge scale of things, I and the turbulence around me are unimaginably small.

FIGURE 3 | Surrounding Mountain (環山圖) by W.Y. Leung

Besides, keeping a certain distance from the painting, the depth of the scene directs me to look beyond. The unclear long shot metaphorically shows me that the future is uncertain but open. The meandering path in the front may reflect the current situation–which it is not easy to walk, and which has some way still to go. Chinese landscape painting echoes what I think at that moment and creates faith and hope. It probably is an ideal image that I am looking for at this moment, without regarding it as a false picture of how things usually are. A beautiful vision can be all the more precious to me because I am so aware of how rarely life has satisfied my desires and made me happy in recent times. It serves the critical function of art as well as expressive arts, which distill and concentrate the hope we need to chart a path through the difficulties of life. It helps guide, exhort, and console its viewers, enabling them to become a better version of themselves in the future.

Conclusion

Art making, in whatever modality, is always responding to a need from our heart. The artwork itself is a metaphor that depicts the person who creates it. It works with the material of the art medium, as much as working with the material of the personality, psyche, and situation, demanding that we grapple with how to make our experience visible in the form of the art piece (Halprin, 2003). Chinese landscape painting does the same. Chinese landscape painting always strikes people with its magnificence and exquisiteness. The interwoven relationship between Chinese landscape painting and the painter exhibits its compatibility with the practice of expressive arts in a few aspects. Chinese landscape painting allows the mind to lead the brush, and the presentation of the brushstroke is influenced by a whole-body participation. Every brushstroke tell us about the outer and inner state of the painter. The work encourages the painter to develop intimacy with themselves. Meanwhile, this embodied experience inspires the painter to develop a different relationship with their daily reality. Being mindful, exercises our senses and opens up the imagination, with the aim of searching for the image which echoes the inner state of the painter that will lead the way and reveal itself.

The Chinese landscape painter does not just reproduce whatever happens to be around them, given the limitations of the painting materials and the change in attention in every moment. The painter experiences themselves as an active changing agent. There is an option to emphasize certain features and omit others, which allows the attention of the viewers to be directed in specific ways. Art is then understood as more than a self-expression, as it connects one’s inner and outer selves, and lets things appear as they are at that moment.

Focusing on doing Chinese landscape painting can help the painter to cultivate a state of mind. It immerses the painter into the “landscape” and gives alternative experiences to physical, mental, and psychological states. It eventually creates a bigger breathing space and allows the painter to stay out of the routine, which, in the expressive arts is called entering into a transitional space. The landscape itself does not articulate its power but articulates its calmness. As a viewer, it lets people keep their eyes wandering over the huge mountain and to be immersed in an attitude of reverence. The sense of being insignificance humbles the viewer in front of intractable challenges. Being attuned with the landscape brings people closer to themselves, inviting them to be more open and embrace life’s challenges. Therefore, the feeling of being stuck in the plight is no longer overwhelming and the fear is no longer engulfing. It helps people learn to surrender to what may come and be self-compassionate.

About the Author

Ms. Wai-yu Leung, REAT, RSW is a Registered Expressive Arts Therapist and Registered Social Worker. She currently works as a social worker in a non-government organization in Hong Kong. She has years of experience of offering counselling services to children and youths. She is committed to the social services of students with special education needs and emotional disturbance. Email: paisleyleung@gmail.com

References

Botton, A. & Armstrong, J. (2016). Art as Therapy. New York, NY: Phaidon Press.

Halprin, D. (2003). The Expressive Body in Life, Art and Therapy. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Knill, P.J., Barba, H.N. & Fuchs, M.N. (2004). Minstrels of Soul: Intermodal Expressive Therapy. Toronto: E.G.S. Press.

Knill, P.J., Levine, E.G., & Levine, S.K. (2005). Principles and Practice of Expressive Arts Therapy. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Levine, S.K. (2012). Nature as a work of art: Towards a poietic ecology. Poiesis: a Journal of the Arts and Communications. 14:186–198.

Levine, S.K. (2019). Philosophy of Expressive Arts Therapy: Poiesis and the Therapeutic Imagination. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Levine, E.G. & Levine, S.K. (1999). Foundations of Expressive Arts Therapy: Theoretical and Clinical Perspectives. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Rowley, G. (1947). Principles of Chinese Painting. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Shaw, M. (1988). Buddhist and Taoist influences on Chinese landscape painting. Journal of the History of Ideas, 49(2):183–206.

Slingerland, E. (2007). Effortless Action: Wu-Wei as Conceptual Metaphor and Spiritual Ideal in Early China. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Xu, X. & Wang, J. (2013). C.C. Wang reflects on painting. Tai bei shi: Dian cang yi shu jia ting.