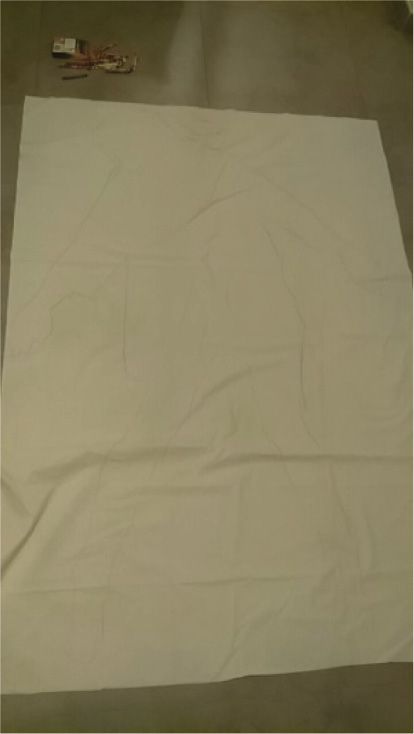

FIGURE 1 | Empty silhouette. 180cm ×130cm. Mix media. © Gracelynn Lau.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2020) 6(2):153–170 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2020/6/22 |

Decolonizing my Hong Kong Identity as a Settler in Canada: An Expressive Arts-based Inquiry

表達藝術本位研究: 從加拿大遷佔者到香港去殖民化身份認同

Queen’s University, Canada

Abstract

This paper documents an intermodel arts-based inquiry through engaging in expressive arts therapy. The author responded to reflexive questions: Who am I as a Hong Kong Chinese Canadian in the indigenous-colonial context of the 21st century? How can I carry my own decolonization through the arts? Carried out in Hong Kong and Ontario, Canada, this inquiry explored indigeneity, settler colonialism, personal and collective history, and family memories.

Keywords: settler colonialism, decolonize identity, expressive arts-based inquiry, Indigenous-settler relations, cultural healing

摘要

作者以表達藝術治療的方法論進行藝術本位研究 (art-based inquiry),探討自身作為加拿大遷佔者(settler) 與香港去殖民化的身份認同,在「原住民 – 殖民者」(indigenous-colonial) 的脈絡下反思加拿大香港移民身份,探討如何透過表達藝術治療深化去殖民化的身份認同。本文記錄作者在香港及加拿安大略省為期三個月的藝術本位研究過程,思考原住民性、遷佔殖民主義、個人與集體歷史,以及家族記憶。

關鍵詞:遷佔殖民主義,身份去殖民化,表達藝術本位研究,原住民—遷佔者關係,文化療癒

Introduction

This inquiry sprang from questioning my positionality as a Hong Kong Chinese Canadian in the indigenous-colonial context of the 21st century Canada, and what are my responsibilities as a researcher working with indigenous peoples in British Columbia. I started out searching for an appropriate indigenous research methodology that I could work from to carry out my doctoral research project. But when reading indigenous pedagogies and methodologies, I realized that the emerging indigenous research paradigms are a collective endeavor of many indigenous scholars, who frame research through their own ontological and epistemological foundations and methods, with the intention of creating space for more indigenous scholars to thrive in the Western dominant academic setting.

As a non-indigenous researcher and self-identified settler of color, I ask myself: How can I approach indigenous research methods without cultural appropriation and disadvantaging others? Relationship is at the very heart of Indigenous approaches to knowledge. It is imperative to locate the researcher-self in relations and be accountable to all relations during and after the research (Kirkness & Barnhardt, 1991; Wilson, 2008). As researcher, I must write myself into the analysis first. Decolonizing my Hong Kong Chinese Canadian identity thus became the preliminary groundwork for my doctoral research.

This paper documented a living inquiry through engaging in expressive arts therapy, while also based on a/r/tography methodology (Irwin & Cosson, 2004; Springgay, Irwin & Kind, 2005). The inquiry was carried out in two parts. The first part took place in Hong Kong from the 2nd to the 12th December 2019, and was begun by creating my body silhouette on a large fabric (180cm ×130cm). I visited indigenous villages and other places in Hong Kong and chatted with the locals as occasions emerged. I watched two documentaries Cedar and Bamboo (2010)1 and From Harling Point (2003)2 to look into the history of First Nations and Chinese overseas workers, and their contact in the early 19th century in British Columbia. Everyday I then responded to the question “Who am I as a Hong Kong Chinese Canadian in the indigenous-colonial context of the 21stcentury?” by engaging with my empty silhouette, followed by spontaneous journal entry after the process.

The second part took place in Canada from the 27th January to the 16th February 2020. It was a process of synthesizing the first part through embodied and poetic inquiry. The guiding questions were “What is decolonization? How can I carry this process through the arts?” This process resulted in a presentation at the Canadian Indigenous Native Studies Association Conference (CINSA) 2020.

Context

The term “settler” is a shorten version of settler colonials, essentially referring to the physical occupation of land as a method of asserting ownership over land and resources (Vowel, 2016). Scholars in settler colonial studies have identified structural privileges of “white settlers” and “settlers of color” (Lawrence & Dua, 2005; Rifkin, 2013; Sharma & Wright, 2009; Wolfe, 2006) who are living in Canada uninvited.

Since Canada’s 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action, there have been discussions on reimagining the ways to describe “settler” and in transforming the indigenous–settler relationship (Corntassel, Dhamoon & Snelgrove, 2014; Koleszar-Green, 2018; Phung, 2011), asking non-indigenous allies to decolonize themselves by embracing feelings of discomfort (Christensen, Cox & Szabo 2018; Morris, 2016) and to create spaces for an indigenous presence within dominant systems (Maracle, 2007; Mathur, Deware & DeGagne, 2011). But the current Coastal GasLink pipeline resistance across Canada has shown that indigenous–settler dynamics remain embarrassingly challenging.

My decolonize-indigenous awareness began 5 years ago when I moved to Vancouver Island from Toronto. I was guided to look at the relationship between the Chinese and the indigenous peoples in Canada. I was blessed to work with indigenous elders and healers; and with their help, I had gone through layers of ancestral and cultural healing. But because I was born and raised in the British colony of Hong Kong in the 1980s, in a Christian family, my decolonization process needed to go beyond the Canadian context.

Hong Kong was the last major colony of Britain. The Qing Dynasty ceded Hong Kong to the British Empire in 1842, which marked the end of the First Opium War and the beginning of a 156-year history of British Hong Kong. The Treaty of Nanjing, one of the first “Unequal Treaties” between East Asian states and Western powers, was signed. In 1860, the Kowloon Peninsula was ceded under the Convention of Peking; In 1898, the Qing Emperor leased the New Territories and 235 islands to Britain for 99 years. In 1984, the British government and the People’s Republic of China signed the Sino–British Joint Declaration, a treaty agreeing that all of Hong Kong would be returned to China at midnight on June 30, 1997. The treaty guaranteed a “one country, two system” policy, which promised the established capitalist economic system and democratic political system remain unchanged for 50 years, backed by the drafting of The Hong Kong Basic Law.

Unlike the colonial context in Canada, the British colonial regime in Hong Kong is considered to be “collaborative colonialism”(Law, 2009). The British had established Hong Kong as a free trade port in the Far East, where local Chinese elites were allowed to practice cultural customs. The colony attracted many Chinese migrants/settlers who either sought better economic opportunities, or fled the political turmoil in China for a safe haven (Mathews, Ma & Lui, 2008). During the Nationalist–Communist Civil War in Mainland China and later the Cultural Revolution, Hong Kong had become “a refugee city on top of a colonial city” (Law, 2017).

Most scholarly work traced the formation of Hong Kong local consciousness to the 1970s, when the postwar local-born generation reached adulthood and became less hesitant in social–political participation (Ma & Fung, 2007; Mathews, Ma & Lui, 2008). Historian John Carroll argued that prior to British colonial rule, a group of comprador capitalists had already developed a unique identity (Carroll, 2005); they were appointed as the leaders of the Chinese community by the colonial government. But archaeologists argued that precolonial Hong Kong inhabitants can be traced back 6000 years ago (Mathews, 1997).

The dynamics of local–national identity had not only driven a large emigration wave to North America in the early 2000s, but also polarized Hong Kong society and simmered negative sentiment towards Mainland Chinese (Yew & Kwong, 2014), particularly towards new immigrants (Fong & Guo, 2018).

Expressive arts and A/r/tography as living inquiry

Expressive arts theory found its philosophical basis in phenomenological inquiry, understanding human existence as being in the world given to a person through their senses (Knill, Levine & Levine, 2005). Drawing on Heidegger’s interpretation of Poiesis, Levine expanded the traditional meaning of Poiesis to a human fundamental way of being-in-the-world by making something new. Thus, Poiesis is not the special preserve of artists who have talents or training in the arts, but it is “the human capacity of shaping the world while being shaped by the world” (Levine & Levine, 2011). In expressive arts practices, staying in the “no knowing” is the key to “know”, for the liminal space is where knowing could arrive. As McNiff asserted that investigative imagination “requires sustained encounters with uncertainty,” that “trusting the process is based on a belief that something valuable will emerge when we step into the unknown.” (McNiff, 1998).

One of the inquiry methodologies applied by expressive arts practitioner-researcher is A/r/tography. The A/r/t in A/r/tography stands for artist/researcher/teacher, resonating with the Aristotelian “three forms of thought”: poesis (art making)/theoria (knowing)/praxis (doing) (Irwin &Cosson, 2004). A/r/tography explores the artist–researcher–teacher roles as connected and integrated identities in a dialectical relationship. As Irwin addresses, “through attention to memory, identity, reflection, meditation, storytelling, interpretation, and representation, the artists/writers/teachers who share their living practices with us are searching for new ways to understand their practices as artists, researchers and teachers. They are a/r/tographers representing their pedagogical positions as they integrate knowing, doing, and making through aesthetic experiences that convey meaning rather than facts.” (Irwin & Cosson, 2004). The typography of the “borderlands”, the “/” in between and connecting the roles/identities, allows the inhabitants of these borderlands (me as an example!) to re-create, re-search and re-learn the terms of the identities as I confront difference and similarity in contradictory worlds.

Hong Kong – Fragments: Body memories map (December 2019)

Video 1: Mom tracing my silhouette

https://drive.google.com/file/d/14M2cuWnrGlbCzSSrfu2Uf6AkKqe8qS2o/view?usp=sharin

Journal entry December 4, 2019 – My body and my mother

I’ve been sick since I arrived 2 days ago. Why am I always sick physically and emotionally in my childhood home? Tonight I asked mom to draw the outline of me as I lay still on the piece of fabric. I began with a spontaneous conscious movement piece to let my body connect with the space and the fabric, until I found stillness naturally. Mom wasn’t sure what to do but she participated. Her hand traced my body with purple and orange crayons, in awkward but intimate silence. My younger cousin witnessed the process by taking video and photos. Spontaneous movement is core to my artistic inquiry practice, but I felt uneasy to move at mom’s apartment. There’s a split between myself in Hong Kong and myself in Canada, a gap that I am reluctant to recognize. Looking at the empty silhouette, I am confused. It stared at me and said, “honour me, so you can sew yourself back together.”

FIGURE 1 | Empty silhouette. 180cm ×130cm. Mix media. © Gracelynn Lau.

Journal entry December 5, 2019 – Nam Chung: where the Hakka used to live

I brought my empty silhouette with watercolour set, and headed to Nam Chung this morning. Nam Chung is located in the inner sea of Sha Tau Kok and is home to a number of Hakka village settlements with a 400 years’ history. Cheung Uk, Cheng Uk, Law Uk and Yeung Uk (“Uk” means Hakka house), the home villages of the Cheung, Cheng, Law and Yeung clans, are still intact; but most villagers had migrated to the United Kingdom in the early 1950s.

I have the privilege to see some of the work created by The Nam Chung-Luk Keng Oral History Project Working Group, a small group who have been working closely with the remaining villagers in the Nam-Luk Coalition. The Hakka are the indigenous people on paper, but today I learned that Hakka 客家 means “guests”. Originally they were from northern China. During the late Tang Dynasty to mid-Ming Dynasty they were “encouraged” by imperial edicts to settle some far-flung parts of the Empire. They gained their name as “settlers”. Are they indigenous if they were also settlers? I remember soon after the “Umbrella Movement”, a radical political group called Hong Kong Indigenous was established in 2015. The founding members were all young activists born in the 90s. Are they indigenous? Should the ones who inhabited the land the longest be considered indigenous? Or should those who uphold the subjectivity and core values of Hong Kong be considered indigenous? Am I indigenous to Hong Kong? Who are Hong Kong indigenous anyway?

FIGURE 2 | Fish pond in Nam Chung. Photo. © Gracelynn Lau.

FIGURE 3 | Nam-Luk Coalition Da Jiu Festival booklet. Photo. © Gracelynn Lau.

FIGURE 4 | Cedar found in Hong Kong. Photo. © Gracelynn Lau.

As I said goodbye to a local villager at Cheng Uk, I saw a small cedar stands across from the pond. I felt a connection instantly. Cedar has been my grounding ally during my time on Vancouver Island. I made medicine with Western redcedar and drank cedar tea. I’d never thought of meeting cedar in this part of the world, and I’d never imagined feeling more connected to a plant being than to an “indigenous” villager person. To honour the plant being, I offered my hair to ask for permission to take a small piece of cedar home for my empty silhouette. I guess I’ve found the first material to fill the gap.

Journal entry December 6, 2019 – The funeral, in Christian style

My mom’s cousin Yuen Kwok-kit passed away last week. Uncle Kwok-kit was part of a large extended family in Dongguan, China that I have only come to know 3 years ago. During my last visit, mom took me to Dongguan, the home village where my maternal grandpa was born. I met my maternal grandpa’s older sister for the first time. She was 91 at the time. Mom said I should call her Gu Po 姑婆 . Like grandpa, Gu Po has seven children. Uncle Kwok-kit was one of the only two who had made it to Hong Kong during the Cultural Revolution. Mom said Uncle Kwok-kit and his older brother swam to Hong Kong. They were the “freedom swimmers”, also known as illegal immigrants (“II”), slipped into the British colony undetected. The British Hong Kongers called them “II” rather than refugees. In 1974, the Hong Kong Government adopted the Touch Base Policy which allowed “II” from Mainland China who reached south of Boundary Street and met their relatives to register for a Hong Kong Identity Card. But those who didn’t make it to Boundary Street would be repatriated back to the Mainland immediately. Mom said that my grandparents had came to Hong Kong soon after World War II when the border was still open, that they had helped many relatives who swam from China and paid ransom to the “Snakehead” 蛇頭 (people smugglers) to secure the release of the “people snake” 人蛇, our relatives.

Today I attended uncle Kwok-kit’s funeral at the Kowloon funeral home. I had only met him twice. His siblings and their families came all the way from Dongguan for the wake last night, and stayed for the ceremony today. Mom told me that Gu Po’s family has roughly 70 people. I met many of my Biu Kau Fu 表舅父, Biu Kau Mo 表舅母, Biu Yi 表姨 and Biu Yi Ma 表姨媽 (different proper names to call my mom’s cousins) and their children for the first time. It was weird and wonderful to explore this complicated Chinese kinship at a funeral. The fact that I don’t speak their language, a Dongguan dialect that sounds slightly similar to Cantonese, makes it even more awkward and embarrassing. But the weirdest of all is that the funeral was held in the Christian style.

Mom was the first among her siblings to convert to Christianity. She was the one who “shared the gospel and saved the family”. Both sides of my parents’ families and their families are devoted Christians, including my grandparents. A few months before uncle Kwok-kit passed away, mom and her siblings “shared the good news” with their struggling cousin in the hospital, and he decided to convert to Christianity too. The funeral was filled with Jesus the Saviour, we’ll meet again in Heaven and peaceful hallelujah, as if my uncle’s ancestors and his earthly personal history across China’s border didn’t matter at all.

I wonder how my relatives from China feel about the Christian funeral. As I watched on a TV documentary, traditionally Chinese families express grief by moaning and crawling on the ground in a noisy fashion; some even hire professional mourners to wail and sob for the dead. They would burn paper-made gold bars, houses, Hell banknotes and iPhones so their loved one can enjoy a luxurious lifestyle in the spirit world. I had never participated in any of those traditional Chinese funerals, but I am glad the Christian style funeral at least kept one Chinese tradition: the comfort feast (解穢酒).

After the funeral, the hosting family would hold a lunch feast to comfort those who have taken part in the ceremony. The feast must serve seven main dishes and one “Tong Sui” (sweet soup), which must not be made with lotus seeds. At the feast, my mom’s oldest cousin wanted to set aside an ancestor plate for uncle Kwok-kit at the table. My Christian aunt said we don’t need to do this, because uncle Kwok-kit is in Heaven with God now. The church pastor then invited everybody to say grace before we ate. I’ve been to many Christian funerals, but today is the first one that makes me realize how deeply Christianity has taken away Chinese cultural heritage from me and my family.

Journal entry December 7, 2019 – Birth certificate and BN(O)

One of this trip’s purposes is to renew the BN(O) passport for my family. BN(O) stands for British National (Overseas), which is a class of British nationality granted by voluntary registration to British Dependent Territories citizens who were Hong Kong residents before the transfer of sovereignty to China on 1 July 1997. Individuals with BN(O) nationality are British nationals and Commonwealth citizens, but not British citizens. Technically speaking, if you were born in Hong Kong before 1 July 1997, you automatically have two nationalities permanently, one of British National (Overseas) and one of Chinese, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). I have kept both nationalities and passports all these years. Now that I am expecting the Canadian citizenship knowledge test anytime, I imagine I will soon have three nationalities.

FIGURE 5 | My old Hong Kong passport and my parents’ marriage certificate.

Photo. © Gracelynn Lau.

FIGURE 6 | My mom holding my birth note issued by the Princess Margaret Hospital.

Photo. © Gracelynn Lau.

When Margaret Thatcher of the UK and Zhao Ziyang of the People Republic of China had signed The Sino-British Joint Declaration, I was 2. Since I was a kid, I insisted to consider myself a Hong Konger, not Chinese. Not until I moved to Canada in 2005, I didn’t realize that it makes no difference here. People would still come up to me and say, “Can you teach me Tai-chi?” “You must know Kung-fu!” In their world, if I look Chinese, I am Chinese.

On 5 August 1583, St. John’s, Newfoundland was claimed as Britain’s first overseas colony under Queen Elizabeth I. Four hundred and fourteen years later, on 1 July 1997, Hong Kong marked the end of the British colonial era as its last major colony in the world. I guess the complexity of my three nationalities will always dance under the shadow of the British Empire, and I will always be “a treaty person” as an uninvited settler of color in Canada, and as a colonized Chinese from the last colony of Britain. The 1984 treaty guaranteed the “one country, two systems” policy for 50 years. By 2046, would the rising sea level put Hong Kong under water?

Journal entry December 8, 2019 – Lam Tsuen: Who are our ancestors?

Today I went to Tai Po Lam Tsuen with my empty silhouette. Lam Tsuen itself is not a village but a valley where 23 villages are scattered, along with five Weitou people’s villages and 18 Hakka villages. Like other old villages in Hong Kong, most of the villagers had moved out to make a living in the urban area. A new generation of organic farmers, artists, and young intellectuals looking for a sustainable alternative have arrived as renters, forming a self-organized local economy and cultural network in the area. I met a few holistic wellness practitioners who have been witnessing the changes in the area for a decade. Since they have been involved in ancestral healing work, I thought it makes sense to explore the idea of decolonization and indigeneity with them.

FIGURE 7 | Mapping on the platform. Photo. © Gracelynn Lau.

But I had a difficult time explaining settler colonial studies in Cantonese. It was especially challenging to discuss settler colonialism in the historical context of Hong Kong, something that none of us are familiar with. I felt the irreducible gap within, as if I could only think about decolonization in English, that my mind couldn’t move as fast as I’m used to when I speak Cantonese. There’s a translation involved, one that is beyond languages. The early Chinese railway workers in BC are my ancestors in the Canadian Chinese context. I can associate with that. But who are my ancestors in the British Hong Kong-Mainland China context? Who were the oppressor and who were the victim? Can I associate myself beyond the oppressed/victim binary? And if yes, with whom?

On a different note, I was startled by the fact that North American indigenous medicine teachings are gaining popularity in the local new age market. Traditional teaching and sacred items like smudging with sage and drumming are used in workshops out of context. Self-proclaimed shamans or priestesses of local Hong Kongers are offering practitioner training. I found it deeply unsettling. I wouldn’t have guessed that decolonization is so relevant in such context, but I don’t even know how to say “cultural appropriation” in Cantonese.

That night, I filled the core of my empty silhouette with photocopies of my birth certificate, my parents’ marriage certificate, a purple dragonfly and my British Hong Kong passport that expired in 1993. I thought I would work with a lot of plants and soil materials in the art-making – when it comes to the body, nature materials are my default go-to – but I didn’t. Instead I filled the torso with old boarding passes and a postcard image of the Kai Tak Airport in the heart of inner-city Kowloon, the old international airport that was closed in 1998. Now my silhouette isn’t empty, but fragmented. I have no idea what to do with the rest of the body.

Journal entry December 10, 2019 – Cedar & Bamboo

I woke up this morning with the desire and urgency to sew. I allowed the needle to navigate its path on the silhouette for an hour. The stitched lines look familiar. They remind me of meridian, a set of pathways in the body along which Qi is said to flow; or the sea routes between the ports of southern China and of Vancouver Island across the Pacific, where tens of thousands of Chinese men had travelled in search of an unpromising better future. Two hundred years later, here I am, threading through the “parallel universes” in this embodiment of me in the 21st century.

Last night I watched Cedar & Bamboo and From Harling Point again. The former is a short documentary produced by the Chinese Canadian Historical Society of British Columbia (BC) Canada in 2010, featuring life stories of four descendants of mixed First Nations and Chinese heritage. It tells the story of the earliest contact between indigenous people in BC and the Chinese workers in 1788, that many Chinese men married indigenous women in Christian ceremonies and the challenges these intermarriage families faced due to the implementation of Indian Act and the Chinese Exclusion Act. The latter is a documentary by Lin Chiu in 2003. It is the story of the Chinese Cemetery at Harling Point in Victoria, BC, where the bones of the earliest Chinese workers “temporarily rested” until they could be brought back to China. I learned from the movie that traditional Chinese people believe that “the soul of a person who dies in a foreign place wanders lost until their bones are returned home”. There’s a Chinese saying 落葉歸根 (fallen leaves return to the roots), meaning those who live or die aboard shall find their way home eventually. It makes sense, but could home not be where I was born? Uncle Kwok-kit was born in the Communist Dongguan; he died and was buried in Hong Kong. What if I’ve taken root where I chose to live, and the root grows deeper than where I was born? I connect with cedar instantly and naturally, but not bamboo. Does it mean I must find my connection with bamboo just because I am Chinese? There was no bamboo in the British Hong Kong. I grew up in a concrete jungle, where trees in city parks were planted in small boxes covered by bricks and cement.

Journal entry December 11, 2019 – Tung Wah Coffin Home

I told my Chinese Canadian friend about my thoughts on “Fallen leaves return to the roots”. My friend was born and raised in Canada, had relocated to Hong Kong for her career; after a decade, returned home to Canada to take care of her parents. Now she bases in both Canada and Hong Kong seasonally. Her family is relocating to Taiwan. I wonder what they think about “Fallen leaves return to the roots”.

My friend joked about dividing her ashes into three parts; Perhaps the best is to scatter ashes at sea, as a significant part of life involved flying across the Pacific Ocean. Like many Canadian-born Chinese who live in Markham, my friend doesn’t even understand what is “the traditional territories of indigenous peoples”. The concept of “settler” is a foreign language.

In regards to “fallen leaves return to the roots”, a friend recommended a movie called Merry-Go-Round 東風破. The film was produced in 2010, commissioned by Tung Wai Group of Hospitals (TWGH) as a commemorative film for the charity’s 140th anniversary celebration. TWGH was the most influential non-religious charitable organization in the early colonial period. The story is based on the true story of Tung Wah Coffin Home, a repository point where Chinese workers who died overseas had waited to be buried in their native soil since 1899. TWGH provided bone repatriation services, arranged funerals, and served as an information center for overseas clans associations, to fulfill the last wishes of many overseas Chinese.

I had no idea that the British Hong Kong had played such role in the global Chinese network during the mid-19th century. I wonder, how many ancestors at the Tung Wah Coffin Home were resting at the Chinese Cemetery at Harling Point in Victoria, BC before?

Video 2: Finished “Body Memories Map” as of December 13, 2019

(https://drive.google.com/file/d/19ZYPMmoblnbX5pPJ9KXbf9Od8ftKm9Pg/view?usp=sharing)

FIGURE 8 | Filled silhouette. 180cm ×130cm. Mix media. © Gracelynn Lau.

Canada – embodied and poetic inquiry with my “body memories map” (January/February, 2020)

The “body memories map” inquiry uncovered pathways to the landscapes that I had not explored before. I was surprised by the richness that emerged, and my ignorance and forgetfulness of Hong Kong’s historical complexity. I was frustrated by my clumsiness communicating between my two cultures on topics that matter to me.

Back in Canada, I was clueless as to how to move forward. Am I repeating the same story of my colonized-self again? This “body memories map”, wrinkled, scattered, and messy, sitting on the floor in my basement apartment. What am I supposed to do with it? Most importantly, what contribution can this inquiry bring to the ongoing dialogue of decolonization and the settler–indigenous relationship in Canada? Can it shed light on building better indigenous allyship?

As I prepared for my presentation at the Canadian Indigenous Native Studies Association conference, my teacher Stephen Levine asked me to do a movement piece by myself. I felt the urge to start by lying on my now “filled silhouette”. I wondered how that would feel?

Video 3: dancing with my “body memories map”

(https://drive.google.com/open? id=1wVsyPjTgqWHp-u7HJhsHplxvHmf_joHu)

I wrapped myself inside the fabric, as if the fabric was my skin, a heavy cover and a burden, a veil and a protection. I crawled in circles, then moved four legged, and then stillness. I felt drawn to turn my face to the “filled silhouette”, I wonder what is her/his name? I felt the fabric on my face. What else is there? A strong sense of care and sadness came over me, I moved into a slow dance. I took myself by surprise, it felt very intimate. After the movement, I wrote this poem:

Our First Dance

Hello stranger

my lover

when nobody’s watching

let us crawl like an animal

we will move slowly

as if limping

as if we something broke

that no one knows

there were tears

I tried not to cry

but I am ready to dance with you

in our own way

when nobody’s watching

we will testify our love

(January 27, 2020. Kingston, Ontario)

As I was writing, Leonard Cohen’s Dance Me to the End of Love started playing in my head. I instinctively knew I must do a take 2 with the song. So I did. I asked if the movement has a message, and it said: “Your undefined indigenous/(de)colonized self is your stranger and your lover. Dance and smell and touch and spin and sit and lean and stay and rest and it’s all good.”

What does decolonization have to do with my awkwardly intimate grief? For decolonization to exist, colonization must be the “Other”. Is the artistic process pointing to spaces beyond this dichotomy?

In another session, Stephen asked me to give a gesture for being a Hong Konger and a gesture as a Canadian; and later gestures for the transition between being a Hong Konger and a Canadian. My body froze and puzzled immediately, but I managed to do a few movement sequences. After the movements, I wrote this poem:

The Historical Sad Song

Invisible grid

repeat one

go slow, carefully

and repeat twice

straight forward

don’t look at me

don’t look at them

and repeat 3 times

90 degree angle

follow the step

they all follow the step

sink in

into the earth

the mother has been forgotten

under the grid

the mother’s breathing

invisibly calling

the air, the fire

into your memory

(February 3, 2020 Kingston, Ontario)

Embodying my identities brought up completely different “knowing” than thinking about my identities. Holding my legs like a steel ball on the ground was my gesture as a Hong Konger; blowing into the air with my arms flying in the air, was my gesture as a Canadian. I wonder what would be my gestures for being Chinese and being a settler? The title of my presentation at the conference is “Your ancestors recognized my ancestors”. I decided to craft it into a movement + monologue. Maybe “I”, as a settler of color, share and being seen in an embodied and poetic space, could open different spaces for indigenous–settler dialogue?

Before I sat down to write the monologue that night, I went out to catch a bowl of snow. A wave of grief arrived, and I started to cry. I let tears drop into the bowl of snow. I watched my tears merging with the snow, melting, until it naturally stopped. I ended up making a pinch pot, using the melting snow/tears to smooth the cracking clay. I titled the bowl “imperfect container”.

Looking at the bowl, I realized that although the process of “decolonizing myself” involved a willingness to be deeply vulnerable, I must not confuse my cultural healing process as decolonization. In the article “Decolonization is not a metaphor”, Tuck and Yung asserted that decolonization is repatriation of land and ways of being to indigenous peoples (Tuck & Yung, 2012). For non-indigenous people, “embodying decolonization” should mean actively showing up politically and culturally to say no to continuous colonization.

FIGURE 9 | Imperfect container. Clay. © Gracelynn Lau.

A person with a broken leg cannot run a marathon; if decolonization and reconciliation is a marathon in Canada, I believe, all settlers must find ways to heal our broken leg first. We must deal with our own colonial cultural healing. This is the basic requirement to showing up as healthy allies.

The presentation themes of ancestors/gesture/embodiment finally all came together. I crafted two improvisation movement pieces to “tell” the search of my “researching-self” journey through embodiment. I then designed a 30 minute participatory movement activity, inviting conference participants to give me a gesture for the self, for their mother, and for their grandmother, and move into a movement sequence together from there.

Conclusion: Let’s pause and breathe...

I would never imagined that this art-based inquiry would have taken me this far, creating dialogues not only between my Western and Eastern identities, but also crossing between the academic/artistic/therapeutic disciplines. The felt-sense and aesthetic process has carried me beyond the analytical and linear ways of knowing, deepening into the untouched territories of my being. In the realm of the aesthetic I found the scattered pieces of my identities and connected them back together, where I conversed with researchers in other disciplines with my vulnerability. As I told my Elder back in the west coast about this journey, she said, “the word ‘decolonization’ goes to the head, but the word ‘disconnect’ goes to the heart.” Could academic research also be a healing process? I wonder. I hope this personal inquiry would spark insights in fellow researchers to take expressive arts-based inquiry further.

About the Author

Gracelynn Chung-yan Lau was born and raised in Hong Kong when it was still a British colony. She moved to Canada in 2005 for her Master’s in Worldview Studies. She is a nature-based expressive arts therapist and sustainable design educator. Since 2015, Gracelynn has been part of the ecovillage movement in BC, Canada, where she facilitates school programs, internship, women’s circles, and sustainable wellness retreats. Currently a PhD candidate in Cultural Studies at Queen’s University, her research looks at the intersection of Indigenous-settler relations, intergenerational trauma healing in expressive arts therapy and social change through arts-based inquiry.

1 Cedar and Bamboo. Lau, J. & Lee, K. on behalf of Chinese Canadian Historical Society of BC (Producers). Leung, D.E. & Todd, K. (Directors). (2010). [Documentary]. Vancouver, BC: Moving Images.

2 From Harling Point. Jacob, S., McCrea, G., Eriksen, S. & Fraticelli, R. (Producer). Chiu, L. (Director). (2003). [Documentary]. Montreal, Canada: National Film Board of Canada.

References

Carroll, J. (2005). Edge of Empires. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Christensen, J., Cox, C. & Szabo-Jones, L. (2018). Activating the Heart: Storytelling, Knowledge Sharing and Relationship. Waterloo, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Corntassel, J., Dharmoon, R. & Snelgrove, C. (2014). Unsettling settler colonialism: the discourse and politics of settlers, and solidarity with Indigenous nations. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3(2), 1–32.

Fong, E. & Guo, H. (2018). Immigrant integration and their negative sentiments toward recent immigrants: The case of Hong Kong. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 27(2), 166–189.

Irwin, R.L & Cosson, A. Eds. (2004). A/r/tography: Rendering Self Through Arts-Based Living Inquiry. Vancouver, BC: Pacific Educational Press.

Kirkness, V.J. & Barnhardt, R. (1991). First Nations and higher education: The four Rs – respect, relevance, reciprocity, responsibility. Journal of American Indian Education 30, 1–15.

Knill, P., Levine, E. & Levine, S.K. (2005). Principles and Practice of Expressive Arts Therapy. London & Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Jacob, S., McCrea, G., Eriksen, S. & Fraticelli, R. (Producer). Chiu, L. (Director). (2003). From Harling Point [Documentary]. Montreal, Canada: National Film Board of Canada.

Koleszar-Green, R. (2018). What is a guest? What is a settler? Cultural and Pedagogical Inquiry 10(2), 166–177.

Lau, J. & Lee, K. On behalf of Chinese Canadian Historical Society of BC (Producers). Leung, D.E. & Todd, K. (Directors). (2010). Cedar and Bamboo [Documentary]. Vancouver, BC: Moving Images.

Law, W.S. (2009). Collaborative Colonial Power: The Making of the Hong Kong Chinese. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Law, W.S. (2017). Why ‘Reunion in Democracy’ fails? The past and the future of a colonial city. Cultural Studies 31(6), 802–819.

Lawrence, B. & Dua, E. (2005). Decolonizing antiracism. Social Justice 32(4), 120–143.

Levine, E. & Levine, S.K. eds. (2011). Art in Action: Expressive Arts Therapy and Social Change. London & Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Ma, E.K.W. & Fung, A.Y.H. (2007). Negotiating Local and National Identifications: Hong Kong Identity Surveys 1996–2006. Asian Journal of Communication 17(2), 172–185.

Maracle, L. (2007). My Conversations with Canadians. Toronto, ON: Book*hug Press.

Mathews, G. (1997). Heunggongyahn: On the past, present, and future of Hong Kong identity. Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars 29(3), 3–13.

Mathews, G., Ma E.K.W. & Lui, T.L. (2008). Hong Kong, China: Learning to Belong to a Nation. New York, NY: Routledge.

Mathur, A, Dewar, J & DeGagne, M. (2011). Cultivating Canada: Reconciliation through the Lens of Cultural Diversity. Ottawa, ON: Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

Morris, K.B. (2016) Decolonizing solidarity: Cultivating relationship of discomfort. Settler Colonial Studies 7(4), 456–473.

McNiff, S. (1998). Trusting the Process: An Artist’s Guide to Letting Go. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Phung, M. (2011). Are people of colour settlers too? In A., Mathur, M. DeGagné, & J. Dewar, (eds.), Cultivating Canada: Reconciliation Through the Lens of Cultural Diversity. Ottawa: Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

Rifkin, M. (2013). Settler common sense. Settler Colonial Studies 3(3–4), 322–340.

Sharma, N. & Wright, C. (2009). Decolonizing resistance: Challenging colonial states. Social Justice 35(3), 120–138.

Springgay, S., Irwin, R.L. & Kind, S.W. (2005). A/r/tography as living inquiry through art and text. Qualitative Inquiry 11(6), 897–912.

Tuck, E. & Yang, K.W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1(1), 1–40.

Vowel, C. (2016). Indigenous Writes: A Guide to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit issues in Canada. Winnipeg, MB: Highwater Press.

Wilson, S. (2008). Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Halifax, NS: Fernwood Publications.

Wolfe, P. (2006). Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native. Journal of Genocide Research 8(4), 387–409.

Yew, C.P. & Kwong K.M. (2014). Hong Kong identity on the rise. Asian Survey 54(6), 1088–1112.