FIGURE 1 | “To think” in Chinese and its imagery.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2020) 6(2):141–152 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2020/6/4 |

Expressive Arts as a Way of Making Meaning and Gaining Insight: An Eastern Perspective with the “Mind”

從東方思想探討表達藝術作為尋找意義與洞見的方式

Expressive Arts Life, Hong Kong, China

Abstract

This article includes two parts. Part I attempts to use one of the Buddhist psychology theories, “five ever-present mental states,” to illustrate how our mind is interconnected and propose how the act of art-making increases the capacity of intuitive thinking and connects feelings and logical thinking with the architecture of expressive arts therapy. Part II illustrates a series of expressive arts workshops, “Expressive Arts as Inquiry” launched for people who wanted to use art for processing, connection, and exploration of themselves in a community classroom for adults. Participants came from different backgrounds. Two case studies revealed how this art-making process brings change with each of them experiencing new ways of thinking/awareness of their different mental states and sense-making through art-making.

Keywords: expressive arts therapy, Buddhist philosophy, perspective, mind, intuitive thinking

摘要

本文包括兩個部分。第一部分作者嘗試使用佛教心理學理論之一「五篇行心所」來說明我們的思想是如何互相連繫,並提出一個表達藝術治療如何增加直覺思維的論述:表達藝術治療如何增加我們的內在空間去處理情感和邏輯思維。第二部分作者描述了她在香港社區舉辦的一個名為「表達藝術探究」的工作坊。參加者來自不同的背景,參與的目的是透過藝術創作以連繫及探索自己。作者透過兩個案例研究描述表達藝術的過程是如何為個案的思維角度帶來改變,他們如何透過藝術創作獲得新的意義及洞見。

關鍵詞:表達藝術治療,佛教心理學,思維角度,直覺思維,意識

Re-think

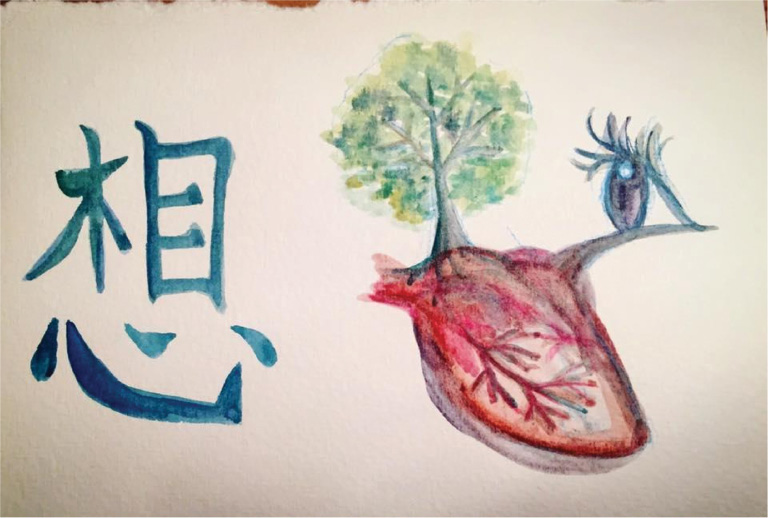

My own research question started in 2016, after my first summer in the European Graduate School for expressive arts (EXA) therapy training. I traveled around Europe for six months, and on one occasion, I joined a volunteer camp about gardening with young people in Germany. One day, we were walking around in the garden and a French volunteer took a leaf from a maple tree and my immediate reaction was to tell him not to, as it is wrong. He asked: “Why not? They are going to fall eventually.” His words stimulated my thinking about where my idea of “picking a leaf from the tree is wrong” comes from, and the answer was found when I was showing a Chinese character “to think” (想) to a Spanish volunteer in the same camp. (Figure 1.) The word “to think” (想) is composed of three parts: “a tree” (木), “an Eye” (目), and “a heart” (心). When I illustrated the word into the picture, suddenly I made sense of what I was looking for.

FIGURE 1 | “To think” in Chinese and its imagery.

I wrote a poem as my aesthetic response to my picture:

What does it mean to think?

Does thinking come from nothingness?

Does it come from the information from someone else?

When we think, we observe.

We observe nature. We make sense.

We connect our feelings with the world.

We process and we make the decision.

What if the current world is the result of thinking with only our ‘brains’?

Is it possible to rethink our thinking pattern in relation to nature, to the phenomenon, to the senses, to our hearts?

It seems to me that our way of thinking is from the perspective of how we see our world—how we perceive it. The origin of “perspective” is the Latin word “perspicere,” which means looking through something. It is related to or limited by the availability of the information, our background assumptions, our states of mind, our location, our feelings, our concepts and norms, and our ways of information processing (Pauen, 2012). When we do not notice our sources of perspectives, it is easy to create a bias toward the world, such as how I thought it was wrong to pick a leaf from a tree.

But how do we notice our perspectives? How do our habitual ways of thinking affect our feeling and decision-making or vice versa?

Re-mind

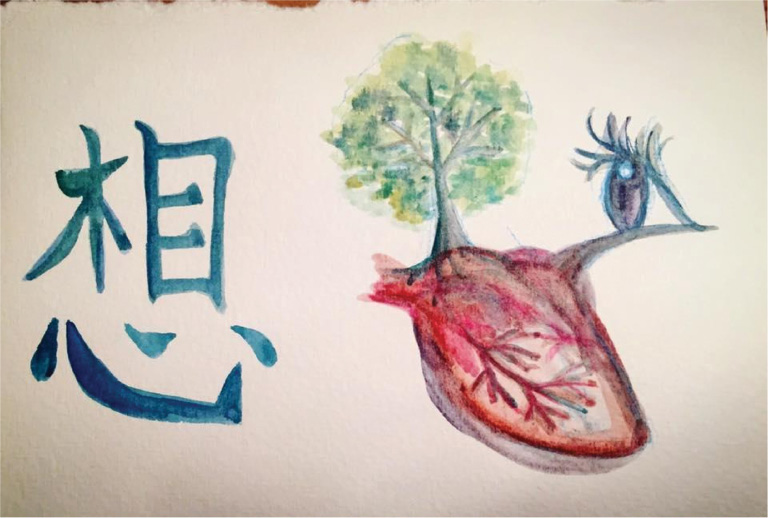

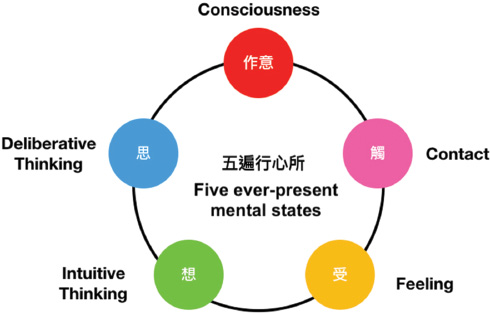

I returned to Hong Kong with these questions in my mind. On one occasion, I went to Tzs Shan Monastery, where I got to know more about Buddhist philosophy and I was inspired by this Eastern philosophy about the idea of the “mind.” There is a model of mental activity called “five ever-present mental states” (五遍行心所) in Buddhist philosophy, which describes the mental states in every activity we encounter with the mind/world. (Figure 2.)

FIGURE 2 | Five ever-present mental states.

Our mental activity begins with a “contact/sensation” (觸) with the world, or the inner world (for example, our thoughts), which creates a “feeling” (受) toward the event outside/inside. This feeling is pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral. The reaction is affected by our “consciousness” (作意), or what we call metaphorically as “big data.” In Buddhist view, this big data is composed of the traces of what our previous experience, memory, and even DNA (the experience of our ancestors) have left to us for reference taking. The feeling toward an item then leads to “intuitive thinking” (想) and “deliberative thinking” (思). Intuitive thinking relates to the imagination, the values of how we process an event or the options for response, whereas deliberative thinking relates to the planning and strategy of the action, which will reinforce the traces in our consciousness (Thich Nhat Hanh, 2001).

Sometimes, we feel stuck, we feel there is no space around an idea or a thought, that there seems to be a lack of options, or that there is a dead-end situation. It is related to the lack of intuitive thinking. Many parts of our everyday lifestyle are routine ways of living, and while we are repeating the same system in schools or companies, there is very little space for us to make a different choice or respond and reflect on different values or even imagine a bigger picture with alternative choices. There is a lack of practice of intuitive thinking, and therefore, our mental activity remains the same (i.e., no update of our big data).

In my experience with expressive arts, EXA can expand the play-range of consciousness by breaking the habitual patterns of thinking. Instead of drilling into a problem using narrowed everyday logic, we can enter into an alternative space of imagination as in EXA, that is, de-centering into art-making, play, and ritual, we enter the logic of imagination, which is also the practice of intuitive thinking. In fact, the architecture in an EXA session is structured well to let our psyche/mental state be ready to operate in the here and now and let the imagination come. I will elaborate by outlining the architecture of EXA and draw a connection to how EXA could contribute to the expansion of intuitive thinking.

Re-imagine

The steps for an EXA therapy session follows the principles of SERV (Knill, Levine, & Levine, 2005), which involve sensitization, exploration, repetition, and validation, and followed by aesthetic analysis and harvesting.

Re-shape

Now, we try to look at the process of an EXA session from the perspective of the five ever-present mental states to see what is happening in our mental state when we are doing EXA, and how EXA “make sense”?

The sensitization toward art materials, such as paper, colors, and musical instrument, as well as the space and speed of movement is the “contact” (觸). This contact then links to our “feelings” (受) about the materials, such as like, neutral, or dislike, and also some associations with our opinions or previous experience in “consciousness” (作意). Usually, when we do not pay attention to ourselves toward the stimulants, we react with our previous reference without new ways of responding. It is an autonomic process. In EXA, however, we keep our attention in the here and now toward the materials. We try to shape the artwork with what has been given. “De-centering” is the approach here in EXA, which means we do not drill into the issue that brings us the suffering; rather, we focus on the sensation of the materials and the process of art-making and welcome the imagination to arrive. This shaping process is where “intuitive thinking” (想) expands. We discover new ways of connections, new forms, and shapes. In group sessions, while we co-create artworks and witness one another, we observe more of an item from different perspectives and we make sense when the artwork is born. An aesthetic analysis connects the nonverbal, bodily art-making experience into a verbal and cognitive process. When intuitive thinking has a chance to connect with “deliberative thinking” (思), this new discovery in an art-making process can leave or replace traces in our conscious mind, which updates the big data in “consciousness” (作意). (Table 1.)

TABLE 1 | Summaries of relationships between EXA and the five ever-present mental states

| Five ever-present mental states | Contact (觸) | Feelings (受) | Intuitive thinking (想) | Deliberative thinking (思) | Consciousness (作意) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expressive arts | Sensitization | Exploration, repetition | Validation | Harvesting | |

What happens in our mental state during EXA |

Prepare our body and mind to be attentive at the here and now, away from habitual thinking |

Connect with our feelings openly and let our imagination arrive to shape the art-making process with curiosity. Explore different ways of connections |

Reflect on the process and product verbally in relation to the aesthetic qualities |

Reconnect with new discoveries in the process into everyday life, update the big data for response |

|

Re-act to Re-think

Inspired by this Eastern philosophy, I tried to conduct a series of EXA workshops in Hong Kong for people who feel stuck in thinking and ideas, which are very common in this modern society where our everyday life becomes overwhelmed with information and stimulations in this highly stressed city. Hong Kong has been rated as an unhappy city with high working hours and low satisfaction. A recent survey has shown that more than 90% of Hong Kong people experience stress. Most spend long hours at work, ignoring family life and personal wellness. I wonder if through art-making we can give ourselves some space to observe our own thinking, our own mind, and our own needs. To search for the question, we want to answer and bring change on an individual or social level.

To begin with, I framed the open workshop as “Expressive Arts as Inquiry” for people wanted to know some of their questions in life with alternative means. A total of six lessons were designed, with the first session beginning with some basic introduction of EXA therapy (i.e., phenomenology and poiesis). I gave two articles for the participants to pre-read, one of those is from a pre-reading by Richard E. Palmer about Martin Heidegger’s work “The Origin of Artwork is Art,” which discusses in Heidegger’s view “Art sets truth into the work,” for having a reference of how art could be a way of answering our question. “Truth is the process of unconcealment,” according to Heidegger (Palmer, 2008). The other article is “The Tao of poiesis: Expressive arts therapy and Taoist philosophy,” by Stephen K. Levine. In his article, he illustrates the relationship between EXA and wuwei, a concept in Taoism. The Tao (道), which also means the way, is one of the original philosophies in China. In Levine’s view, the essence of wuwei is quite similar to the state of de-centering in the art-making process in EXA (Levine, 2015). Therefore, I use it as a metaphor, as it may be an easy connection for my group of Chinese audiences to make. Next, I tried to illustrate that the architecture of each session begins with filling in, de-centering into the art-making process, and harvesting. A clear framework helps the participants become grounded and know what is going on in the next step.

Each session was designed with one or two specific art mediums without a specific theme. The participants came with their own intentions or questions, some of them are interested in knowing more about what is EXA, some of them want to know how EXA could help their creativity, and some of them want to relax with art-making.

Response

The following are two case studies from the EXA sessions. Both of them have joined all six sessions. A follow-up interview was carried one week after the completion of the course with a set of questions, including how they feel about the process of the sessions, what stands out, what is helpful, and if they realized a change in everyday life after participating in the course.

Case 1: Ms. Yu is a former senior manager in a corporate company, dealing with big data analysis. She came to the workshop with an intention to know more about how arts could be expressive. She thinks of herself as one who lacks creativity and is always locked in the same way of thinking. After a series of sessions within two months, she described herself being able to enter a process of change:

“The information at the first session about the structure of a session and de-centering away from everyday logic and into the imaginative logic sounds understandable, but the problem is how to enter into it? After joining for the first three session, I found myself able to enter that process but I don’t know how. I couldn’t explain to my friends what am I doing, it is like entering into a crazy world.” (Figure 3.)

FIGURE 3 | Process of “Expressive Arts as Inquiry.”

“But I noticed the change in myself after every session. After the first session, I experienced a relaxation in my brain. I have never experienced that lightness of my brain, like it doesn’t need to work and is able to turn off some functions. The second session, I experience a different way of thinking in my head, like there are individual ideas popping up simultaneously, I found it difficult to handle because it is unfamiliar for me. This feeling gets better after the third session, when we have to perform an improvisational drama play. I was afraid and worried that I couldn’t make it (the play). However, with your encouragement, as you said ‘We already have the story inside.’ I suddenly feel confident to do it, and the play actually helped me to connect those scattered ideas in my mind into something concrete.”

We had a two-week break between the first three sessions and the rest of the sessions. After coming back, Ms. Yu enjoys more of the creative process:

“During those two weeks, I have time to reflect about what is happening during a session and make sense of what you have said at the very beginning about the structure of a session, so I feel more familiar and comfortable to get into the process of art-making and change. After the fourth session, I found that my capacity has expanded. Previously I was very sensitive to reading. For example if there is too much information from a page then I couldn’t continue the reading. After the art-making, I found myself able to receive more information without being overwhelmed.”

Between the fourth and the fifth sessions, there was an outbreak of social movement in Hong Kong in June 2019. In the fifth session, the participants felt especially tensed; thus, I spent some time doing some relaxation breathing exercises. The medium for that session was clay work, and everyone was able to open up and share their emotional stress. Ms. Yu entitled her piece of clay work “The Inequality of Love,” expressing her doubt of what the adults could do for the kids in the current social and political situation. Other participants also shared worries, frustrations, and anger at that time through the clay work. After the session, when we were leaving the studio, we received the news of the first activist who had committed suicide, jumping out of one of the buildings nearby, and Ms. Yu witnessed before she came to the class that night.

“I felt completely empty inside, no sensation, no feelings, no temperature. I stayed awake until 3am couldn’t sleep at all. Then I wrote a few words... actually a short poem and posted a photo on my Facebook. I seldom do this as it is too sentimental for me. However, after making this post, I gradually got back some feelings, and was able to think again.” It was one of the most surprising moments for Ms. Yu over the whole series of sessions.

“The last session was very insightful, towards a new future.” In the last session, we created a dance from a line drawn by each participant with feedback from a partner, the theme of “planets” emerged from the group dance, and I asked them to draw a planet and name it. Ms. Yu drew a few similar circles on the same paper for her “Planets” with the title “No Identity is Good.” “The picture actually answered a question in me which I have been thinking about for a while, and I didn’t bring it into the class on purpose. I was taking a break from my career and was searching for a new position. My identity was tied strongly to my previous work which I enjoyed. But for the new job I wanted, I have to remove this outstanding identity, and somehow it is difficult for me to accept. However, this picture speaks to me that it is okay to be without an identity, and it is a relief.”

From the sharing of Ms. Yu, we can see that she has realized a way of thinking different from her usual habit (the individual ideas pop up simultaneously, which we may call intuition or images coming to reach us). Working in research and development for a long time, her usual way of thinking or investigation is based on a third-person perspective and opinion, and she always jumps to the conclusion quickly. As she tries to practice this alternative way of thinking/art-making, she gains a new perspective of observation, which is the observation of herself. She found the space inside expanded and is able to receive more information and is also able to express her feelings (i.e. the previous reaction to receive stimulation has been changed) bit by bit. If we look back to the model of five ever-present mental states, it makes sense to us that when the range of intuition increased, we also altered our ways of response to the contact and feelings, that is, the reference in our big data has been updated through this process.

Case 2: Ms. Ma was taking a break from her work in an NGO in mainland China. Due to a heavy workload, she experienced burnout at work and returned to Hong Kong for recovery. She has anxiety, which is inhibiting her ability to know which direction or action she should take or even what she wants to do. She describes that there were a lot of heavy objects in her mind, all sticking together and that she could not see them clearly before she joined this EXA workshop.

“This art-making journey for me is like a journey of jumping out of boxes and boundaries and letting the imagination flow. I remember one session where we decorate a chair with threads. That process allows me to focus on the present moment with the touch of the soft knit. I was able to connect with myself and ask myself ‘what do I want?’ It was a very rare but essential moment for me ... usually at work, we focused on the needs of our clients but never ask ourselves ‘what do I want and what do I need?’ I found that this kind of art-making under the support of other participants and without judgment helps me to go back to the deeper part of myself and the root of my confusion. It creates a space for a dialog with myself.”

“I remember there were a few sessions that we needed to use our body to express...in drama and in dancing. After that I noticed I have a split between my body and my mind, that I seldom pay attention to my body and ask what she wants. I started to get interested in watching the movement of the human body and went to watch some dance shows. I am aware that my observations of the body has increased and maybe I could join some dance class to let the body move.”

“After each art-making process, when I have finally created the artwork, I feel like the heavy objects in my mind have been thrown out into the real space and now I can take a look at it from a distance. I feel relaxed and relieved that I could see things from a more objective angle, or from more than one angle, without being affected by the emotion.”

“I can embrace and listen to more voices from different perspectives and opinions without getting angry. I feel myself becoming more open, broadening my inner space, which I was lacking. And this increase in space also increases my ability to be able to search for the truth.”

What she mentioned is also about the outbreak of social movements in June 2019 during our fifth session. Her clay work shows two human figures holding each other, facing a bullet, representing the students and the tear gas released by the police force. She found that the artwork helps her hold her feelings so she can listen to more opinions at that time.

From Ms. Ma’s sharing, we can see that the flow of imagination helps her settle her overwhelming feelings and realize her own limited perspective. When she noticed this, she is able to withstand more voices, or what we in EXA say, the range of play increased and helps her to find a systematic way to search for the truth/fact. From the five ever-present mental states model, we may again say that the practice of intuition through art-making helps to shift the mind activity from feelings to other activities such as intuitive and deliberative thinking and brings changes in our big data.

Re-search

The above two cases illustrated my questions of what happens in our mental state while doing EXA and how the arts help us in expanding the capacity for knowing our ways of thinking and expand the ways of response in a situation. For me, I also learned something through this “Expressive Arts as Inquiry” process: that the answer to the questions we asked in life could be other questions and the process of making art together helps us to stay curious about our questions and remove the barrier of looking into it.

In November 2019, Paolo Knill and Margo Knill visited Hong Kong in the midst of unease while the protest was ongoing. We asked Paolo what is the future of EXA. He replied, “the future (of EXA) is to shape a new way of thinking of how we share the world, that we are all in the same ship….” I shared my experience of “Expressive Arts as Inquiry.” I told Paolo that I found out that sometimes the answer to the question we asked can be a question. He replied, “The answer can only be and must be a new question…for re-search is a continuous process.” This reminds me again that we have the ability to update the big data in our consciousness. An answer may become another fixation in our mind, but a question will challenge our installed views and stimulate our “intuitive thinking” process for seeing a bigger picture, a bigger world view. We make meaning and gain insight through art-making and expand our intuitive thinking capacity.

I still remember in the last session how we used movement and visual arts to explore how we are within the situation of unease. We started with moving freely in the room and improvising into a dance, the group came out with the theme “Stars in their own orbit.” (Figure 4.) I then invited them to draw their own stars with soft pastels.

FIGURE 4 | Theme: “Star at Its Own Orbit” visual artwork.

Quite a few of the participants have the theme of “It’s okay to stay in the chaos” and “It’s okay to be tedious” as the name for their “star.” This theme reminds me of another concept in Taoism wuyong (無用), which means “purposiveness without a purpose” by Zhuangzi. I am surprised that this theme emerged at this time to show the contrast against mainstream society’s singular definition of success, which is being purposeful and useful (有用). It is a powerful but essential discovery. The artwork reminds us again about the importance of art, creativity, imagination, and intuition. All of those are part of our human nature and the resources we can use to restore capacity in our human mind in order to see things clearly with new perspectives.

For me, the process of re-search is itself a creation of hope, an opening for possibilities to come to life, cultivating our ability to see a better world, and shaping it out with the collaboration with one and others.

Together we sail the same ship toward the future.

About the Author

Sarah Ying Chui Chu is an expressive arts therapist and registered physiotherapist. Sarah has devoted many years of treatment experience to the importance of body awareness and emotional expression to the health of the body and mind. Now, she actively integrates expressive arts into holistic therapy, community culture, and daily life. At the same time, she is committed to participating in academic research related to expressive arts therapy. Her research interests include expressive arts and Buddhist philosophy, arts and neuroscience, and the arts and burnout syndromes.

References

Knill, P., Levine, E., & Levine, S. (2005). Principles and practice of expressive arts therapy: Toward a therapeutic aesthetics. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Levine, S. K. (2015). The Tao of poiesis: Expressive arts therapy and Taoist philosophy. Creative Arts in Education and Therapy (CAET), 1(1), 15–25. Retrieved 1 December 2015, from http://caet.inspirees.com/caetojsjournals/index.php/caet/article/view/5

Palmer, R. (2008). A reading of Heidegger’s the origin of the work of art (1936): Art, work, and truth. Retrieved 1 February 2008, from http://lms.ctl.cyut.edu.tw/sys/read_attach.php?id=912472

Pauen, M. (2012). The second-person perspective. Inquiry, 55, 33–49. Retrieved 18 January 2012, from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0020174X.2012.643623

Thich Nhat Hanh. (2001). Understanding our mind: Fifty verses on Buddhist psychology. Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press.