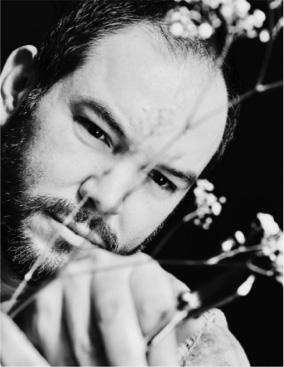

FIGURE 1 | Ikebana, Ikenobo School, courtesy of Reginaldo Bockhorni.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2019) 5(2):96–108 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2019/5/35 |

From Ikebana to Botanical Arranging: Artistic, Therapeutic, and Spiritual Alignment with Nature

从花道到园艺治疗:与自然在艺术,治疗和精神层面的契合

1Saint Petersburg Academy of Postgraduate Pedagogical Education, Russia

2Ikenobo Zurich Study Group, Brazil/Switzerland

3Inspirees Institute, China

Abstract

This article reviews the history of the Japanese art of Ikebana and the contemporary ecological art therapy practice involving botanical arranging and their correlation and contribution to the physical and mental well-being of human beings. Different perspectives are offered by a Brazilian Ikebana professor, with a neurological background, from the Ikenobo School, a Russian art therapist specializing in ecological art therapy, and a Chinese creative art therapist with a biomedical background. Ikebana and botanical arranging are considered forms of creative interaction with nature, providing multiple therapeutic effects and showing us how to realign with the laws of nature.

Keywords: Ikebana, Japanese arts, Zen Buddhism, Ecological therapy, Arts therapies, Art expression, Botanical arranging

摘要

本文回顾了日本花道艺术的历史以及包含园艺治疗的当代生态艺术治疗实践,并审度了两者与人类身心健康的关联和影响。一位来自巴西的日本花道学院具有神经医学背景的花道专家,一位专门从事生态艺术疗法的俄罗斯艺术治疗师和一位生物医学背景的中国创造性艺术治疗师提出了各自不同的观点。花道和园艺治疗被视作与自然创造性互动的形式,具有多种治疗效果,并向我们展示了如何重新顺应自然法则。

关键词: 花道,日本艺术,禅宗佛教,生态治疗,艺术治疗,艺术表达,植物布置,园艺治疗

Ikebana: Reflection of Japanese and East Asian World View

Ikebana is one of the important traditional Japanese arts and has been in existence for 600 years. The word Ikebana, which is composed of ikeru (生 け る, keep alive) and hana (花, flower), means “giving life to flowers.” It is also called kadō (華 道 or 花道), which means the way of the flowers. Ikebana originated from China, derived from the Buddhist tradition of offering beautiful objects to the dead, mainly in the temples. In the 7th century, Ono-no-Imoko, an official envoy, brought the practice of this Buddhist flower arrangement on an altar from China to Japan. While ikebana continued to be part of Buddhism in China, it became a real art in Japan. It was an early sign of the Buddhist integration into Japanese religious and social practices. Contrary to the art of flower arrangement in the Western world, where the quantity of flowers seems to have a high priority, Ikebana reaches far beyond the philosophical ideas of beauty and forms a cultural world view, centered around ideas of living in harmony with nature. In Japan, nature has always been the highest manifestation of truth and beauty. Japanese poetic attitude to nature remains a strong feature of Japanese culture (Danylova, 2014). In Ikebana, attention is focused on the lines, asymmetry, space, contrast, and harmony (Fig. 1). Nowadays, it is considered as a disciplined art form in which nature and human creativity are brought together. Ikebana requires technical skills and is backed by solid theory. This form of art remains a vital medium for creative expression. Similar to the other practices in Japan like calligraphy, tea ceremony, and Haiku, which have been valued in Zen Buddhism as a means of self-cultivation, Ikebana is seen as one way of body–mind training. Immersion in the physical practice of this art can lead to both psychological and spiritual emptiness (no-self), which is thought to be the source of skillful action and the basis for empathetic and ethical behavior. Self-transformation is the result of such diligent practice. The reduced role of the humble artist allows objects to reveal their inner essences (Hovane, 2017). The health benefits of Ikebana practice in enhancing the well-being of both patients and the general population are supported by some empirical and evidence-based research (Hannemann, 2006; Sasaki, Oizumi, Homma, Masaoka, Iijima, & Homma, 2011; Watters, Pearce, Backman, & Suto, 2013; Homma, Oizumi, & Masaoka, 2015). In modern society where abundance, wealth, and egoism are mostly valued, Ikebana brings the notion of simplicity, modesty, and gentleness to the foreground and reminds us that the power of nature and human beings does not necessarily come from the Yang or the “condensing” quality (i.e., strong, direct, free, and quick). Interestingly, until the 18th century, ikebana practice was only for men. Such appreciation toward similar quality of arts and practice can also be found in the Four Arts (四藝, siyi): qin (the guqin, a stringed instrument. 琴), qi (the strategy game of Go, 棋), shu (Chinese calligraphy, 書), and hua (Chinese painting, 畫), which were the four main academic and artistic accomplishments required of the aristocratic ancient Eastern Asian scholar-gentleman.

FIGURE 1 | Ikebana, Ikenobo School, courtesy of Reginaldo Bockhorni.

Unlike other art forms, Ikebana directly employs materials from nature, which thus builds up an explicit connection to nature and embodiment experience for Ikebana practitioners. The traditional structure of Ikebana arrangements has three main stems emerging from a central point and often forms the shape of a harmonious triad symbolizing unity among the heavenly realm, humans, and the earth. The human body is thus very much present in the composition that forms the basic entity to interact with the universe. Different body organizations such as radial symmetry, head/tail, upper/lower, homo lateral, and cross lateral are the patterns visualized in Ikebana. Grounding and center of gravity/levity can be felt on the plant as well as our own body. Dynamic alignment and body phrasing can be projected to the flowers and plants. Ikebana masters usually integrate the breath, spatial intent, and different body movement quality when creating Ikebana. This level of sensing and embodiment are the basics of the practice. During this ritual, which requires strong personal presence, the rhythm and pattern of breathing is adjusted and aligned with flowers and nature. Our breath is strongly associated with Ch’i, which is interpreted as the vital energy, moving power, and psychophysical energy in East Asia (McNiff, 2016). Apparently, through this alignment process, human beings get empowered via this Ch’i from nature. This Ch’i further enhances our creativity and artistic expression. On the feeling level where the energy and dynamics are the main parameters, the inner drive toward weight (strong/light), space (direct/indirect), time (quick/sustained), and flow (bound/free) is manifested by the construction and composition of the flowers, and even by the cutting of the plants themselves. The indulging and condensing energy can be used as a strategy to create Ikebana as well as a way to exert and recuperate during this creative process. Although Ikebana presents a still form at the end, the whole process of creating is an interactive and dynamic “dance” between human beings and flowers and with nature at the physical, mental, and spiritual level. The wider the spectrum of the movement and the clearer the intention of the “dancer”, the richer the interaction will become. The art of balance is essential: structure/freedom, symmetric/asymmetric, stability/mobility, outer/inner, self/other, part/whole, all implemented in the Ch’i (flow) of an Ikebana master who has the eye for detail and the appreciation for creativity and spontaneity.

In Ikebana, emphasis is rather placed on accentuating the lines and individual shapes of each flower, leaf, and branch. The surrounding empty space is just as important as the materials themselves. The Japanese ma (or Mao, 冇, in Chinese), for the concept of interval or void in both time and space, is full of energy and feeling instead of “negative space,” which is highly valued in Zen meditation. Ma creates rhythm and flow, engaging the viewer with the composition. Ma allows us to understand that “less is indeed more.” The space element of Ikebana triggers our thinking regarding the general space, our inner space, as well as our kinesphere (personal space) in terms of different spatial zones, reach space, and pathways (central, peripheral, and transverse). Different points in the space as well as the dimensions (vertical, horizontal, and sagittal) are taken into account.

Besides space, the Ikebana practitioner is consistently creating relationships with the flowers and reaching the environment eventually. That requires the intuition of a person. How do we see the still shape form of ourselves and the flowers to give a clear self-image that will be brought to the flowers? How strongly do we focus on ourselves with our physical sensations before we open ourselves to the flowers? How do we interact with the flowers and environment? Is it a spoke-like direct reaching or more art-like indirect reaching? How capable and comfortable are we to accommodate ourselves to the other (flowers, space, environment), which sometimes requires more three-dimensional shaping from us? What kind of rhythm or pattern do we decide to make this relationship?

The motif becomes one of the characteristic symbols of Ikebana and a tool to remind us to project our worldview to the flowers. With its simplistic concept and presentation, Ikebana requires the concentration and mindfulness of practitioners to create the clear motif of the flower arrangement. This is usually the single-task action that is nowadays not often and easily practiced in our daily life and work. Thus, Ikebana helps us to experience the other deficient polarity of the duality that is essential in keeping ourselves in balance with others and with nature.

Ikebana involves “human interventions” with the cutting and arranging of flowers and spaces. But eventually we realize it is not a human intervention but an interaction with nature, and a process for us to learn to realign humanity with the laws of nature. This process can be interpreted as the practice of wu-wei (无为), widely described as “non-action” in Taoism tradition, which is a person’s innate and authentic virtue (te/de, 德) action/expression in accordance with the movements of nature, an approach that carries within itself a timeless guide to well-being (McNiff, 2016).

Ikebana and Ecological Art Therapy

Although ikebana remains one of the symbols of the Eastern cultural traditions of China and Japan based on their philosophy and artistic, ritualized daily practices, it assumes a new meaning and role in the context of the contemporary globalized environmental, ecological movement. This movement, together with many other effects, brought new significant implications for contemporary psychology and therapy, creative/expressive arts therapies, in particular. Throughout the last two decades, such new scientific disciplines as environmental psychology, ecopsychology, and ecotherapy, with their concepts and practices, have been brought into fruition and helped us understand ikebana from a new, environmental perspective.

Nowadays, a significant increase in the use of various ecotherapeutic, nature-assisted environmental therapies applied on different clinical and nonclinical populations with therapeutic, rehabilitation, and preventive purposes is observable. As global culture becomes more urbanized, clinicians are increasingly looking for strategies to optimize the beneficial aspects of nature into a client’s life. Findings from numerous studies support the premise that contact with nature is beneficial for human health and well-being (Burls, 2007; Heerwagen, 2009) and support human growth and development in cognitive, emotional, spiritual, and aesthetic domains.

Botanical Arranging as an Ecotherapeutic Expressive Activity

Botanical arranging, an ecotherapeutic activity, has certain connections to ikebana on the conceptual and practical levels. Botanical arranging draws its theoretical model from the literature and research of art therapy, ecopsychology, and horticultural therapy. Botanical arranging is focused on the use of cut flowers, greenery, and other botanical ephemera as a metaphorical and artistic modality. Botanical arranging implies a helping practitioner, such as an art therapist, a horticulturist, an occupational therapist, or other therapist, facilitating the creation of simple arrangements of botanic materials as an art product on the part of a client and then studying it for embedded meaning with a client. Botanical arranging establishes an affiliation with horticultural therapy and ecopsychology/ecotherapy by integrating organic materials into an art therapy approach.

Montgomery and Courtney (2015) emphasized that when botanical materials are utilized in art therapy, the client and the therapist may engage in another dimension of feeling and association not present with nonorganic materials. Botanical products are evocative in ways that may be personal, ancestral, experiential, or archetypal in different layers of conscious and unconscious awareness. Plants enter a spectrum of experience through color, symmetry, scale, texture, scent, and shape whose attributes merge with an individual’s own history. These are primary sensory impressions that belong to a preverbal, prenarrative world—the biophilic (Kellert, 1993; Wilson, 1984, 1993) component of human experience. Simply touching, smelling, and arranging botanical ephemera into pleasing symmetries can bring pleasure, alertness, and a sense of accomplishment.

Formulated by Wilson in 1984 (Wilson, 1984, 1993) and then elaborated by Kellert and Wilson (Kellert, 1993), the biophilia hypothesis is described as the “innately emotional affiliation of human beings to other living organisms” (Kellert, 1993, p. 31). Kellert (1993) presumed that it is a “human dependence on nature that extends far beyond the simple issues of material and physical sustenance to encompass as well the human craving for aesthetic, intellectual, cognitive, and even spiritual meaning and satisfaction” (p. 18).

Montgomery and Courtney (2015) believed that an increase in the varieties, structures, and types of materials, including vines, leaves, fruits, flowering branches, and seed pods, as well as flowers, yields a richer, more complex visual and psychic field for the client’s exploration in art therapy sessions. “Culturally, flowers for adornment in wedding celebrations, liturgical practices, and memorial traditions, among others, all indicate that there is an emotional content to flowers whose presence often signifies personal transformation. Thus, botanicals acquire metaphorical vitality that individuals may experience at conscious and unconscious levels of experience. Within this interwoven relationship, it is unsurprising that botanicals become signifiers of specific human events as a part of the common language” (p. 19). According to Diehl (2009), flowers can release neurochemicals that help “eliminate pain, induce sleep, and create a sense of well-being” (p. 170).

Botanical arranging as a form of ecological, nature-based art therapy can be a viable expression of the art of biophilia (Kopytin, 2016, 2017), defined as a form of creative activity in and with natural environments (green spaces) supported by biophilic reactions. Creative acts as perceived from the art of biophilia or ecopoiesis perspective (Kopytin, 2019) are rooted not so much in the need of individual creative self-expression in the traditional sense of the word, but in the motivation to support and serve nature and life and achieve nonduality, a balance between natural and cultural milieu by embracing the transpersonal center of being (Davis, 2011).

The process of botanical arranging occurs in three phases: preparation, experience, and debriefing of the experience. The first phase introduces clients to botanical arranging as an ecological art therapeutic activity and to the materials needed for a session, then some warming-up indoor or outdoor exercises aimed at awakening sensory awareness through touch, taste, smell, etc., of natural spaces, objects, and materials and providing change in the modes of environmental perception takes place. Setting a focus related to the topic of the session; choosing a question or situation that could be most relevant for the day can be also included in this part of the session.

The second phase is the actual working session wherein clients create an art product using botanical ephemera and interact with it or through it with themselves and the environment, installing their creations in the landscape or using action-based creative activities such as performance, dance and movement, personal or group rituals, or multimedia events. More concentrated forms of reflexive and creative activity such as journaling and creating narratives can be also implemented in the session. In the third phase, clients step back from their creations and observe and discuss their work for insight.

Assignments related to botanical arranging can be open-ended or based on certain themes. Open-ended assignments encourage participants to walk outdoors in the environment or explore natural materials indoors and pay attention to scenery or objects they find most interesting or appealing for them and select materials. Mindful interaction with the natural environment and botanical materials are considered the significant component of sessions.

Case Example 1: Botanical arranging as a result of a meditative journey in the institutional green area accompanied with selection of natural materials

A mixed group of helping professionals took part in a brief wellness-focused supportive art therapy program with the goal of learning ways to develop self-regulating stress management skills and mindfulness based on their creative interaction with the natural environment. The 3-hour weekly sessions included art-making with the use of environmental botanical ephemera as a mindfulness practice.

In the beginning of one session, the therapist offered the group the possibility to spend one hour outdoors in order to explore the institutional environment of the community center where sessions took place, an enclosed field with sports ground and some wild plants and apple, pear, and birch trees. The therapist explained that the participants are allowed to select and use any type of organic materials available on the institutional ground including vines, leaves, fruit, branches, seed pods, wild flowers, and other botanical ephemera as well as stones, soil, sand, and water, but not to destroy any life, if possible.

Participants were encouraged to take a meditative journey through the environment and find some natural materials and objects in order to arrange a small botanical arranging. The therapist recommended participants to use small ceramic containers, plates, or cups up to 12 cm in diameter as a holding space for their creations. The therapist also encouraged the participants to find some place in the environment to install their art work and arrange the surrounding area, if needed. Later, they were invited to present a brief performance, a ritual in the environment, and somehow interact with their creations as meaningful objects. This part of the session followed with participants’ sharing their experience and the meaning of their performances and creations.

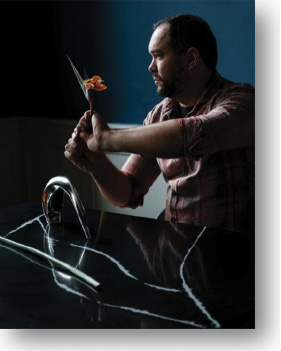

While presenting his art work, a 62 year-old man, a university teacher, was sitting on the bench below the birch tree and holding his botanical arranging in his right hand and an apple in the left hand (Fig. 2). He explained his performance in the following way:

“The apple is a symbol of ecological learning and the birch tree is a symbol of my connection with nature. I also created a composition by [I] putting water and the burning candle in the vessel. I meditated for a while sitting on this bench under the birch tree and holding the vessel in the right hand and the apple in my left hand. I felt tranquility and I was inviting great powers of nature in the form of water, fire, earth and air to be with me and around me. I was absorbed in the peaceful state of mind. I felt being grounded in the mystery of life.”

FIGURE 2 | Group participant performing his ceremony.

While sharing their experience and effects at the end of this session, the participants mentioned their improved affective state of decreased stress and energetic restoration. Some of them emphasized that by exploring the environment in their meditative walk, creating their artworks, finding and arranging a place to install them, and interacting with their creations in the environment through rituals and other activities, they felt being physically, emotionally, and spiritually connected to the natural environment.

Case Example 2: Botanical arranging as a form of environmental art expression with substance abuse clients

Art therapy was carried out with substance abuse clients taking a course at the specialized rehabilitation center in St. Petersburg. The course is attended by people aged 30–60 years who have problems with the use of psychoactive substances. The majority are alcohol-dependent (70%); the rest are drug addicts in remission. Approximately 10% of the clients use the so-called new drugs (salts, acids, hallucinogens). Men make up about 80%, whereas women comprise 20% of the rehabilitated clients.

Some sessions implied creating botanical arranging from natural materials, mostly from botanical ephemera found in the environment, with the goals of relieving emotional tension, multisensory and emotional stimulation, supporting mindful interaction with the environment, cultivating a sense of beauty, raising environmental consciousness, and improving self-perception and self-understanding.

Botanical arranging and other forms of environmental art activities using natural materials and found objects took place regularly during the course. In some cases, participants were invited to go outside for a while and, while walking in the park, especially in autumn, collect natural materials they like. Returning then to the studio, they were asked to create a composition from them, for example, in the form a botanical arranging (“green mandalas”), using cardboard plates as the basis for its construction.

One of these sessions was held in the second half of September 2018. Having created simple botanical arrangement from natural materials found and discussing the work and their impressions of the lesson, the participants noted that they could see the beauty of simple things, how surprisingly diverse and harmonious are the shades and shapes created by nature itself. The beauty of natural ephemera has become more apparent due to the organization of the found materials into simple compositions (Figs. 3 and 4). The participants also noted that as a result of a relatively short walk outdoors (15–20 minutes), their emotional state improved and a feeling of joy and their satisfaction from the activity increased.

Describing his botanical arrangement made of leaves in the form of a mandala, Valery (name changed) (alcoholism, 57 years old) said that it resembles his life, in which different colors were mixed. He associated the left side of his “green mandala” with his childhood, while the middle part of his artwork, made of leaves with different shadows, was associated with the present period of his life, and the right part, with its yellow and reddish hues, is associated with future. Valery considered an acorn located at the top of the composition as the symbol of rebirth (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3 | Botanical arranging made by Valery.

Rooslan (name changed) (alcoholism, 48 years old) realized that his arrangement reflects running in a circle, but with a stronger intention to come out of the circle and to bring his talents associated with acorns into fruition.

FIGURE 4 | Botanical arranging made by Rooslan.

In general, the participants were satisfied with their work. At the end of the lesson, they took photographs of their botanical arranging for memory and again went to the park to sow acorns.

Interview with Reginaldo Bockhorni

Tony Zhou (TZ), the executive editor of CAET, one of the coauthors of this article, interviewed Reginaldo Bockhorni (RB), an Ikebana professor at Ikenobo School, who shared his personal and professional experiences with Ikebana.

TZ: You were born in Brazil and later on trained as a neurological specialist in Parkinson’s disease. All these sound quite distant from Ikebana. What attracted you to this route? How do you think the art and medical science get crossed and benefit each other? Do you feel there is a specific link between Ikebana and neuroscience?

RB: Brazil has a large Japanese community, and in my family, there are some Japanese influences. Ikebana is very well-known in Brazilian society, and I have always been interested in learning this art. It came into my life as a hobby and has turned into a profession. I believe what attracted me most in this art was the respect for life and nature. Ikebana means bringing flowers to life. It requires patience and perseverance and can also be very relaxing. I remember practicing ikebana after an intense day of work helped me to calm down. I believe that when your eyes are focused on something so beautiful, it makes you feel positive and relaxed. It can sometimes be so emotionally beautiful that flowers, leaves, and branches can offer you this. By training, I am a specialist in the treatment of neurological-chronic diseases (Parkinson’s/Multiple Sclerosis) and have worked in a hospital setting for over 15 years. Hospital care is about life and death, about treating diseases and keeping people alive. The disease areas that I was working in are chronic diseases, meaning that until now the medical community has not succeeded in finding a cure. People affected by these diseases will need care throughout the rest of their lives. We will do our utmost best to provide the patients with the best possible treatment and care, to keep them alive for as long as possible. Respect for life is what unites everyone working in health care. Without it, you cannot work in this area. I believe the same is true for ikebana. If there is one parallel between the two worlds, it is the respect for life.

TZ: Looking back your own path in life and profession, you have moved a lot. Was there any special reason that mobilized you? How did Ikebana help you deal with all these changes?

RB: My life’s journey has brought me from Brazil to Europe, and in Europe to various countries. While studies and work have been the reasons for moving, ikebana has always been with me. And it has changed me. I feel calmer, I have a lot of patience to listen and to teach. I can express more feelings through ikebana than before. When practicing ikebana, you will sometimes spend hours working on an arrangement. Whether alone or in a group, you will be the only one working on your arrangement, and this means that you will be on a personal journey until you have completed it. During this journey, you will be confronted with your thoughts, related or unrelated to the arrangement you are working on. Your mind will wander off; you will need to focus; you will have to learn to control your internal conversation. This will bring you closer to your feelings and will help you recognize them and allow them in. When I decided to move to Switzerland along with my partner 1.5 years ago, I knew I would start all over again: new friends, new students, and new challenges. Thanks to years of Ikebana practice, instead of feelings of uncertainty and fear, I was calm with feelings of curiousness and anticipation. Because Ikebana is like that too. Every day, you have new material to learn to use in a creative way. And no matter where I am, I can always fall back on ikebana.

TZ: How did Ikebana transform your emotional world and influence your identity and perception toward the world?

RB: Ikebana itself is another world. When you visit an ikebana exhibit, you notice that all people leave with a smile on their face and become very relaxed. I think it is because you live in the world of beauty, in the world of the pursuit of perfection; where there is no visual pollution. Ikebana fills your eyes and your mind with beautiful things.

TZ: Ikebana, as a creative and elegant form of art, seems to carry the Yin quality. How do you, as a male medical professional and Ikebana teacher, perceive and interpret this art?

RB: Until the 18th century, ikebana was solely for men. Women were only allowed to assist and clean. Nowadays, all the professors in Japan are men, but most students and practitioners are women. Personally, I think it is very special to see fragile flowers in the hands of men; I think men can be very creative. When we make a very big arrangement, we see that for men it is much easier to cut, nail, and carry heavy branches. I also see that men have a greater perspective of asymmetry or symmetry when they need to measure, compare, and calculate the space of large arrangements. At the same time, women are incredibly important for ikebana, and the daughter of the current Headmaster of Ikenobo School will become the future Headmaster.

TZ: How does Ikebana help you to understand different layers of relation: self-others-nature/universe?

RB: I believe in three different layers: flora, fauna, and the human. Trying to understand plants, animals, and humans for me is already an art. I believe we can learn from each other, and there must also be respect for each other. The most interesting for me is that where there are flowers, there are people.

TZ: What are the biggest challenges and crisis human beings are facing at this moment? How can you, as an Ikebana professor, contribute to the advancement of human understanding and evolution via your artistic practice?

RB: Due to the modernization and digitization of our society, people have less contact with nature. There is less time to appreciate trees, plants, and flowers. Most young people today cannot name five different flowers or know where a pineapple or fig comes from. There is much talk about the environment, conservation, and care, but when did you last plant a tree, plant, or flower? When do you take the time to enjoy a flower at home? Ikebana ensures closer contact with branches, leaves, and flowers. You develop patience and creativity and express your feelings to improve beauty through your arrangement.

About the Authors

Alexander Kopytin is a psychiatrist, psychotherapist, and professor in the Psychotherapy Department at Northwest Medical I. Mechnokov University, the head of postgraduate training in art therapy at the Academy of Postgraduate Pedagogical Training at St. Petersburg, and the chair of the Russian Art Therapy Association. He introduced group interactive art psychotherapy in 1996 and has since initiated, supported, and supervised numerous art therapy projects dealing with different clinical and nonclinical populations in Russia.

Tony Y. Zhou, PhD, is the director of Inspirees Institute, China/Netherlands. He is also the founder and executive editor of CAET. He was trained as the biomedical scientist and later on received training in dance/movement therapy and is the first certified movement analyst in mainland China. He cofounded International Association of Creative Arts Somatic Education in 2019. ORCID:0000-0001-8099-6458.

Reginaldo Bockhorni is a Professor graduate in Ikebana Floral Art Ikenobo at Kyoto. He is president of Ikenobo Zürich Study Group and gives classes in Holland and Switzerland. He is also Master Advanced Nurse Practitioner in Neurology (Parkinson and Multiple Sclerosis).

References

Burls, A. (2007). People and green spaces: Promoting public health and mental well-being through eco-therapy. Journal of Public Mental Health, 6(3), 24–39.

Danylova, T. (2014), Approaching the East: Briefly on Japanese value orientations. International Journal of Social Science and Management, 2(8), 4–7.

Davis, J. V. (2011). Ecopsychology, transpersonal psychology, and non-duality. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 20(11), 137–147.

Diehl, E. R. M. (2009). Gardens that heal. In L. Buzzell & C. Chalquist (Eds.). Ecotherapy: Healing with nature in mind (pp. 166–174). San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books.

Hannemann, B. T. (2006). Creativity with dementia patients. Gerontology, 52, 59–65.

Heerwagen, J. (2009). Biophilia, health and wellbeing. In L. Campbell & A. Wiesen (Eds.), Restorative commons: Creating health and wellbeing through urban landscapes (pp. 39–57). Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service.

Homma, I., Oizumi, R., & Masaoka, Y. (2015). Effects of practicing ikebana on anxiety and respiration. Journal of Depression and Anxiety, 4(3), 187–190.

Hovane, M. (2017). Ikebana: The Japanese “way of the flower.” Nov 20, 2019, retrieved from https://www.zenvita.com/blog/ikebana-the-japanese-way-of-the-flower.html.

Kellert, S. R. (1993). Introduction. In S. R. Kellert & E. O. Wilson (Eds.), The biophilia hypothesis (pp. 18–25). Washington, DC: Shearwater Books/Island Press.

Kopytin, A. (2016). Green studio: Eco-perspective on the therapeutic setting in art therapy. In A. Kopytin & M. Rugh (Eds.), Green studio: Nature and the arts in therapy (pp. 3–26). New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Kopytin, A. (2017). Environmental and ecological expressive therapies: The emerging conceptual framework for practice. In A. Kopytin & M. Rugh (Eds.), Environmental expressive therapies: Nature-Based theory and practice (pp. 23–47). New York: Routledge/Francis & Taylor.

Kopytin, A. (2019). The green book of love: History, psychology and ecology of intimacy. Moscow: Cogito-Centre.

McNiff, S. (2016). Ch’i and artistic expression: An East Asian worldview that fits the creative process everywhere. Creative Arts in Education and Therapy, 2(2), 12–20.

Montgomery, C. S., & Courtney, J. A. (2015). The theoretical and therapeutic paradigm of botanical arranging. Journal of Therapeutic Horticulture, 25(1), 16–26.

Sasaki, M., Oizumi, R., Homma, A., Masaoka, Y., Iijima, M., & Homma, I. (2011). Effects of viewing ikebana on breathing in humans. The Showa University Journal of Medical Sciences, 23(1), 59–65.

Watters, A. M., Pearce, C., Backman, C. L., & Suto, M. J. (2013). Occupational engagement and meaning: The experience of ikebana practice. Journal of Occupational Science, 20(3), 262–277.

Wilson, E. O. (1984). Biophilia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wilson, E. (1993). Biophilia and the conservation ethic. In S. R. Kellert & E. O. Wilson (Eds.), The biophilia hypothesis (pp. 31–40). Washington, DC: Shearwater Books/Island Press.