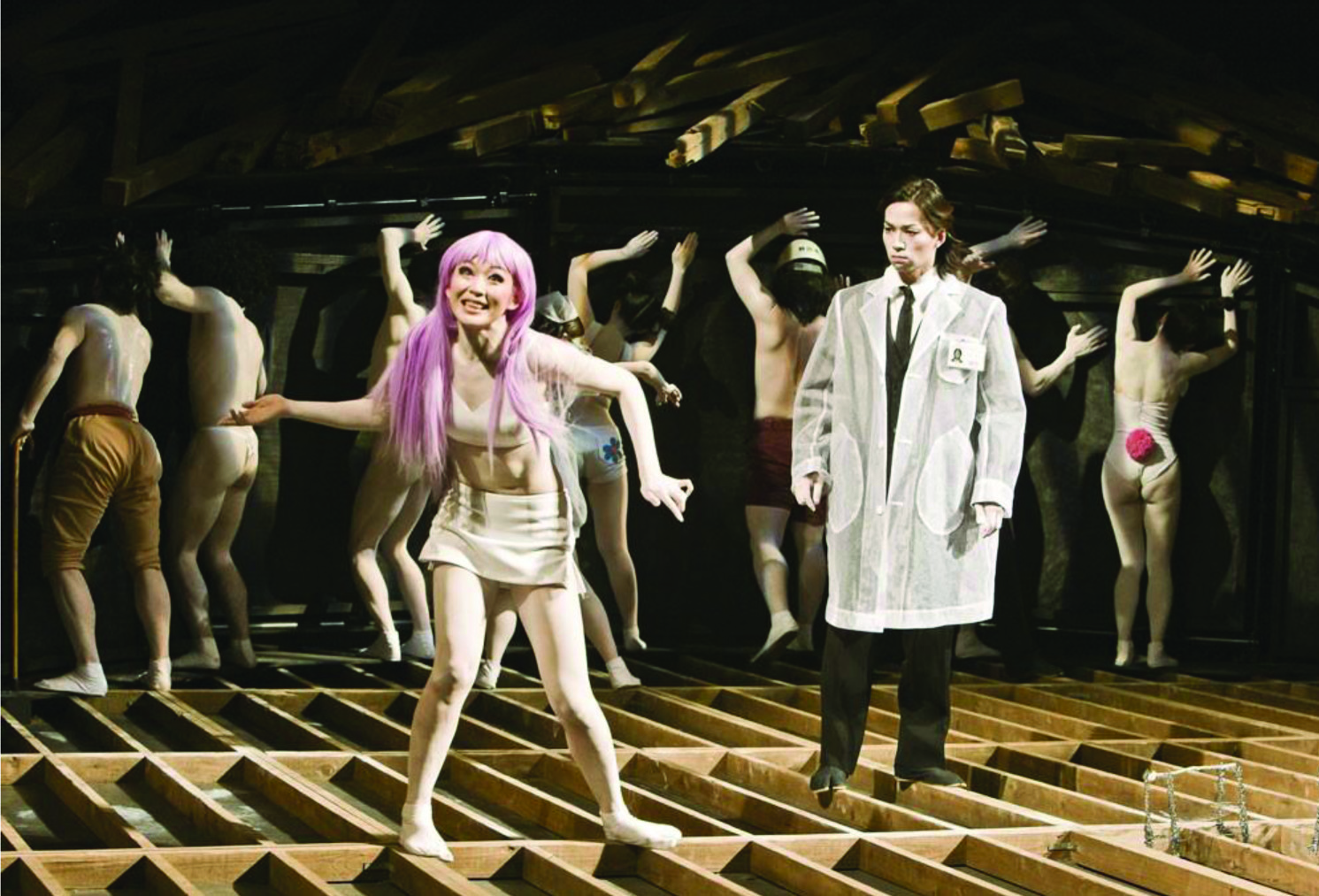

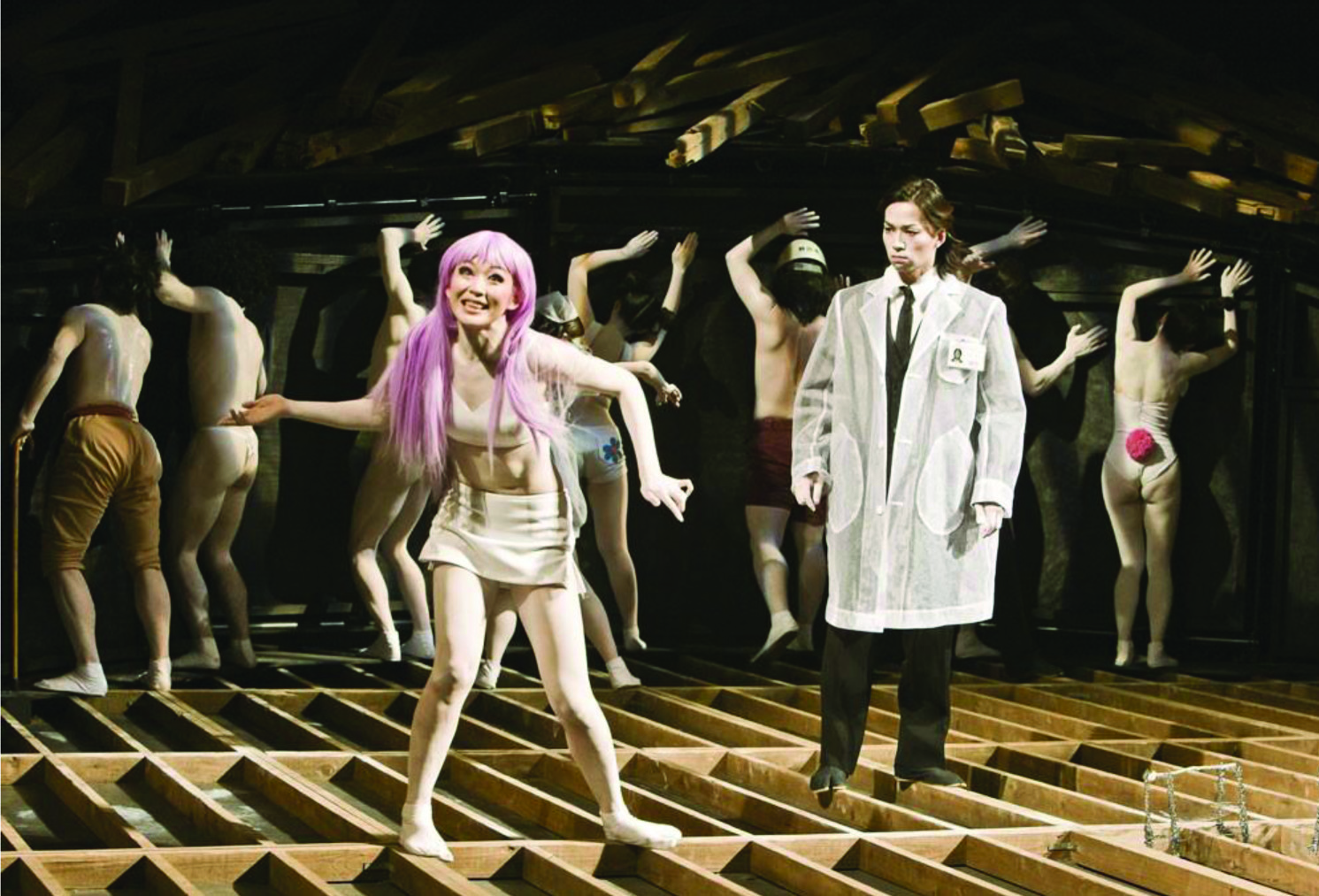

FIGURE 1 | Two Women by SPAC at Shizuoka April-May 2015.

http://spac.or.jp/top2/15_two-ladies.html

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2019) 5(1):25–32 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2019/5/4 |

A Review of Eye Eye Nose Mouth and Reflections on the History of Art and Psychiatry in Japan

“眼鼻嘴”评述及对日本艺术精神病学史的反思

Keio University, Tokyo, Japan

In Japan as well as in many other countries, outsider art or art brut, which is art created by self-taught artists who are often artists suffering from mental illness, is becoming established. Japan welcomes large exhibitions of major outsider artists from other countries and Japanese works are exhibited in major cities in the world. Metropolitan cities such as Tokyo, London, Paris, and many others have hosted major exhibitions of artworks by patients with mental illness1. Smaller-scale exhibitions are popping up in many public and private galleries. Psychiatrists, artistic curators, and art organizers are now publishing and translating books on outsider art in Western countries and in Japan (Hattori, 2003; Watanabe & Kobayashi, 2018). The Japanese translation of Bildnerei der Geisteskranken (1922), the major work of Hans Prinzhorn (1886–1933) from the University of Heidelberg, who began collecting paintings, drawings, and other works of patients from all over the world (including Japan), finally appeared in 2014. It has taken almost a century for Japan to follow the model of Europe, as some of the Japanese intelligentsia may complain about.

Eye, Eye, Nose, Mouth: Art, Disability, and Mental Illness in Nanjing, China and Shiga-ken, Japan is based on the exhibition at the Asia Center of Harvard University. This exhibition is another piece on the rise of the intersection of art, disability, and mental health through the display of original works on paper and sculptures by people with a disability or mental illness. These artworks were originally created at Atelier Yamanami in Shiga-Ken, Japan, and at the Outsider Art Studio in Nanjing, China. As Raphael Koenig and Benny Shaffer, the two curators of the exhibition and the editors of the catalogue, have clarified in the introduction, the two workshops in Japan and China belong to distinct sociocultural contexts and are at different stages of their respective histories. The former was founded in 1986, whereas the latter, founded in 2006, is comparatively smaller. Mental illness and mental disability are particularly complex issues in both Japan and China due to prevalent social stigma, and in the case of mainland China, the relative lack of state-supported care facilities makes the situation more difficult. Both workshops thus constitute attempts to heighten public awareness of these issues and to improve the symbolic images and practical living conditions of affected persons in their respective societies.

Exhibitions of the work of patients/artists with mental illness are new in the contemporary period. For psychiatry itself, the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries were periods of development and improvement as well as of confusion and disturbance. Japanese psychiatry has finally turned from the growth of psychiatric hospitals to the reduction of the number of psychiatric beds in the government’s mental health plans (Goto, 2019). We have also started to recognize that patients have experienced posttraumatic stress disorder due to the Asia and Pacific War, and we can now discuss the mechanisms of this stress and reasons of our previous ignorance (Nakamura, 2016, 2019). With the introduction of these new developments in psychiatry, we need to begin a series of innovations for the representation of the patients’ activities and expressions. Koenig and Shaffer have done an excellent job in creating one of the first exhibitions that combines academic research and patients’ or consumers’ activities and expressions of their own mind. Japanese and Chinese patients are now able to express their own emotions through drawing, painting, and sculpture in a newly created artistic space.

At the same time, we can look at continuities in the exhibition of artists with mental illness in Japan, China, and other countries (Bailey, 2018; Gilman, 1982; Killen, 2017; Vinitsky, 2017). In this historiography, one can see that Japan as well as China had a long history of exhibiting the discourse, activities, and experiences of persons with mental illness. The two types of interpretation of continuity and discontinuity can co-exist: the latter emphasizes the innovation of contemporary practice and the former tries to find the continuities from the ancient, medieval, or early modern period. This review will take the former historiography and emphasize the aspects of continuity in the long history of the exhibition of mental illness.

The starting point might be the Noh theatre, which enjoyed a culmination around the fourteenth century and has been firmly established in Japanese culture. Classical Noh dramas are still performed in various contexts. Although the performance in the original language is rather difficult to understand due to the medieval Japanese, there are many modernized versions of Noh dramas. The issues of life, reproduction and death have been introduced into Noh theatre, and philosophers and bioethical scientists discuss such problems in these dramas (Sasaki, 2019). Psychiatric issues have been also introduced in the modern discussion of Noh dramas. The highlight is Lady Aoi, which was one of the most popular Noh dramas, originally written in the fourteenth or fifteenth century (Tyler, 1992; Zeami et al., 2017). The story was taken from Tale of Genji, which is an eleventh-century masterpiece in Japanese literature. The story of Lady Aoi focuses on a type of ménage à trois involving a male aristocrat, his wife, and his lover. The lover expresses her love, fury, jealousy, and envy in the form of the loss of herself that possesses the wife. This drama interested Mishima Yukio (1925–1979), who modernized this drama in 1956 by situating it in a psychiatric hospital, in which psychoanalytical interpretations prevail and the wife is depicted to have a mental illness and is confined in the hospital. Impressed with this modernization of a medieval drama, Donald Keene translated Mishima’s script into English in 1957 (Mishima & Keen, 2009). Likewise, Kara Juro (1940–), one of the leaders of modern drama in Japan, created another version of Lady Aoi, titled Two Women, which was published in 1980 (Kara, 1980). In summary, the story, which was originally created in the eleventh century, was turned into a Noh drama in the fourteenth century and was turned into several works in modern Japanese using the updated setting of a psychiatric hospital and psychoanalysis [Figure 1]. It was also translated into English and Persian, although I have not read the Persian translation. Lady Aoi indeed represents the long history of the exhibition of mental illness.

FIGURE 1 | Two Women by SPAC at Shizuoka April-May 2015.

http://spac.or.jp/top2/15_two-ladies.html

Mental illness has been featured in other various forms of performance in Japan. While Noh was for the upper echelons of society, Kabukih as expressed popular culture since the beginning of the seventeenth century. It is a well-established and expansive world of drama, which has active dancing and lively music. Kabuki also introduced the issues of mental illness on the stage. In many kabuki dramas, mental illness, possession, and animistic figures appeared. Double Wankyu (Ninin Wankyu), which was produced in the eighteenth century, was somewhat inspired by a real event. Wankyu, a wealthy merchant who falls in love with a courtesan, becomes insane and is confined in a cage in his house, but he escapes and has delusions of dancing with the woman. The Proper Upbringing of a Young Lady at Mount Imose (Imose-yama Onna Teikin) was also created in the eighteenth century, which depicts women’s mental illness. It is similar to Western drama and became very popular among audiences from European and North American countries in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Watanabe, 2012). Incorporating the dramatic representations as well as literary features such as novels, vocal performances such as rakugo, and pictorial expressions of prints, mental illness, possession, monsters, and supernatural beings was prevalent in many of these genres.

From the latter half of the nineteenth century, Japan was in the crucial period of development in introducing Western psychiatric frameworks, which changed the Japanese landscapes of the exhibition of mental illness. Usually psychiatrists were critical to the exhibition of the patients or the cases of mental illness, and in the long run, they were often successful. The simple Westernization model was, however, far from a reality. Westernization went in different directions, and the Japanese had different reaction showing that these new directions were different from the complex components of Japanese traditions. There was a difference between believing in the influence of ghosts and in the power of possession. When the government conducted a national survey, which was published in 1949, it showed that an overwhelming majority of Japanese did not believe in ghosts, but that their belief in possession remained strong: in urban areas, only about 40% denied the possibility of possession, and in rural areas, more than 60% admitted the possibility of possession (Meishin Chosa Kyogikai, 1949). Japan continued its own culture of mental illness for a long period of time. There were several reasons for this. It was partly because the patients and their family members kept their own layman’s understanding of the culture of mental illness. The domestic view of mental illness had somewhat different aspects to that of general understanding. Another important reason was the Western transformation of modernism and surrealism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. That was the age of modernism, surrealism, mysticism, and many other super naturalistic movements in Europe, and the Japanese had these cultural movements, which had a close connection with psychiatry (Micale, 2004; Scull, 2015).

Tradition continued to develop, resulting from new tools to mix with the European ones. The Madness of Onatsu (Onatsu Kyoran), a new dancing program in Kabuki, which was first performed in 1914, represented the style of the mixture of conventional culture and the European expression. It was based on the real story of a woman with mental illness in the seventeenth century, and the story was adapted for many songs, novels, and dances. This is thus a continuation of Japanese traditional representations. Very interestingly, the dramatist was Tsubouchi Shōyō (1859–1935), a great scholar of English drama and the first translator of the works of Shakespeare into Japanese. Shōyō incorporated the Western themes of such women with mental illness as mad Ophelia and crazy Kate, which were somewhat fashionable around that time, into the Japanese traditional themes and created one of the most successful dancing programs of the period. Another example is a film, Page of Madness (1926), whose director was Kinugasa Teinosuke (1896–1982). Coworkers for the film included Kawabata Yasunari (1899–1972), the first Japanese Nobel laureate in literature, and other famous literary figures. The initial inspiration for this film came from Europe, Das Cabinet des Doktor Caligari (1920), which was about patients with mental illness, psychiatrists, and street entertainers in a psychiatric hospital or in a market. To adapt this film into a Japanese setting, Kinugasa visited an asylum in Tokyo and incorporated both the story of Japanese domestic virtues and the performance of Western dancing into this film (Kinugasa, 1977). A further mixture of traditional and European modernism is Dogra Magra, a masterpiece of the detective genre in Japan. The author was Yumeno Kyusaku (1889–1936), who visited the psychiatric department of Kyushu Imperial University very often, read psychiatric papers and books, and incorporated Japanese and Chinese stories into this narrative of a murder in a psychiatric hospital (Yumeno & Honnoré, 2003). These cases of Kabuki dancing, the modernist film about mental illness and the family, and the detective story in the psychiatric hospital were all combinations of Japanese and Chinese traditions with the developments happening in Europe.

Psychiatry also contributed to the continuation of tradition, or, to be more precise, using new facilities and new ideas to deliver traditional messages. Psychiatry had several divisions. The observation of various pathological changes and microscopic chemical indices of the brain in the post-mortem specimen were based almost on the silence of the patients (Shorter, 1997). Meanwhile, the patients’ case histories were full of discourse on what had happened in the minds of the patients. As the case was one of the major frameworks for the medical treatment and administration of patients and talking was an important identity for the patients, the patients’ voices were routinely recorded and often published. Psychiatric textbooks, monographs on specific topics, and articles in journals included many voices of patients. Kraepelin’s textbooks for students and doctors, French patients’ autobiographies that appeared in articles, and patients’ stories in the United States were all vital parts of the development of psychiatry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Peniston & Erber, 2007).

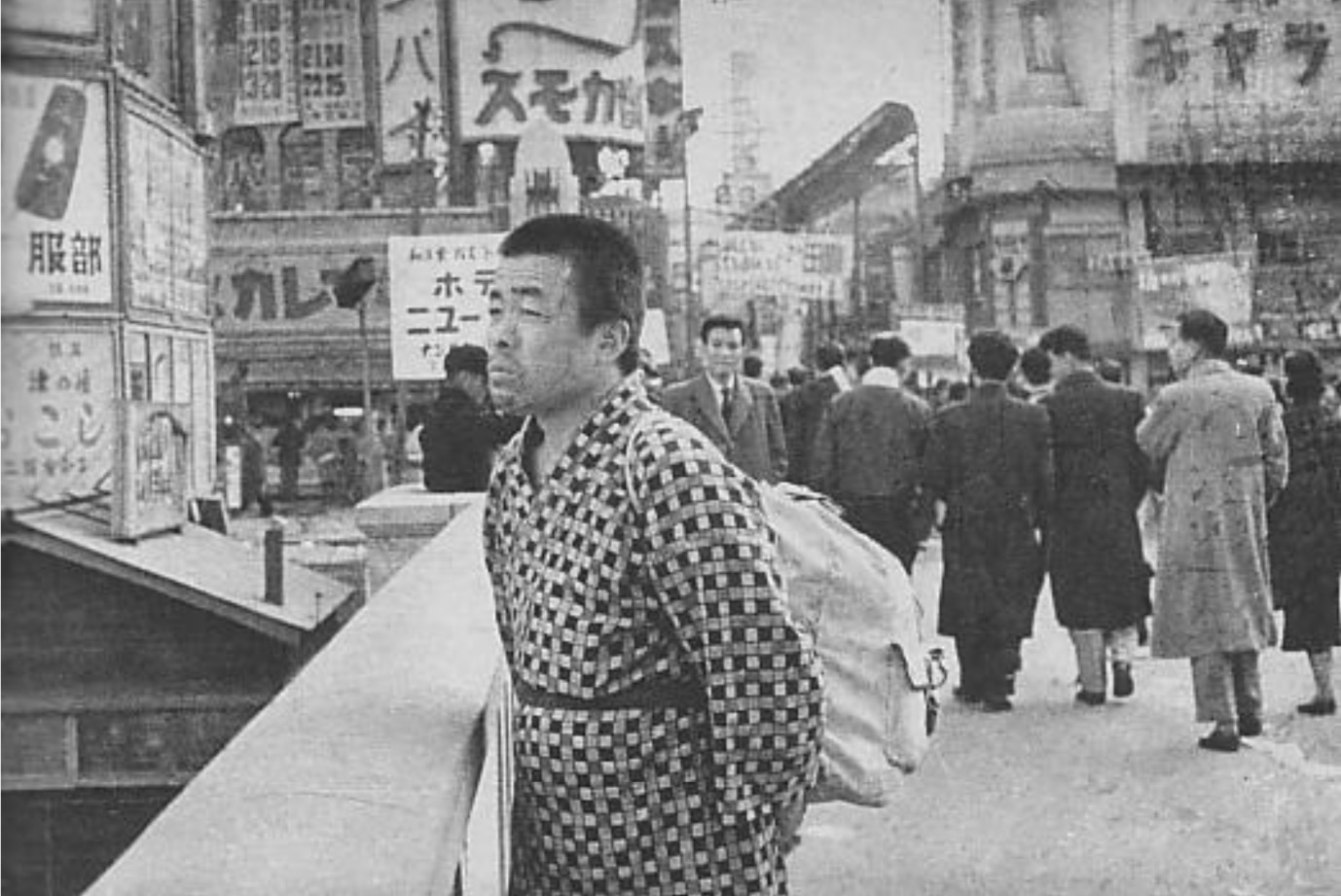

Japanese psychiatrists and psychologists worked with patients to create a space for the patients’ productivity. Yamashita Kiyoshi (1922–1971), who had mental illness from the late 1930s until his death, was the first well-known artist who became nationally famous (Ozawa, 2008; Hattori & Fujiwara, 2014) [Figure 2]. Yamashita was born in Tokyo to a poor family. His father was Ohashi Seiji and his mother was Yamashita Fuji. The father worked as a cook and the mother had various small jobs. They moved from one place to another, mainly in Tokyo. In 1923, after the great Kanto earthquake, they returned to Niigata, the birthplace of both his father and mother. Yamashita experienced medical problems while there which left him with an intellectual disability. His father died in 1932 after suffering from paralysis due to too much drinking. The mother soon had a second husband, who also drank too much and occasionally inflicted violence on family members. His stepfather’s violence and the general poverty of the family finally in 1934 pushed Yamashita into Yahata Gakuen, an essentially private school for intellectually disabled children in Tokyo. There, Yamashita started to exhibit his remarkable skill in the arts such as making collages with colors using unusual types of materials such as discarded stamps. In 1939, artists and scholars arranged an exhibition of the artworks of the boys of Yahata Gakuen. Influential artists and scholars in Japan were impressed by what they saw and the skill of Yamashita particularly stood out. Yasui Sotaro (1888–1955), a leading painter, and Togawa Yukio (1903–1992), a Professor of Clinical Psychology at Waseda University, were both great supporters of Yamashita. In the following year, in January 1939, the Asahi Newspaper organized an expanded exhibition at Osaka and attracted intellectuals, in addition to artists and psychology scholars, to view Yamashita’s works as well as others by people with mental illness. In December 1939, the artists’ society organized a major exhibition at central Tokyo’s Ginza. Major newspapers and leading journals published enthusiastic reviews, especially about Yamashita. One of the articles appeared in the column entitled “Eye, Ear, Mouth,” as if almost predicting the title of the exhibition “Eye, Eye, Nose, Mouth” organized at Harvard in 2019.

FIGURE 2 | Yamashita Kiyoshi at Ebisu Bridge in Osaka, 1955

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiyoshi_Yamashita

The rise of Yamashita from an initially disabled child to an impressive painter had several components, which were often contradictions. One was the rise of positive eugenics which encouraged disabled people to contribute to the economy of his or her household or to the power of the state (Robertson, 2010). Japan, in the earlier half of the twentieth century, had essentially only a small government assistance as regards welfare and relied heavily on the individual, family, and extended households to make disabled people useful in society. The campaign to encourage people with disabilities to work could be found in many literary spaces. Komatsu Sakyō (1931–2011), one of the most successful science fiction writers in Japan, left a memoir about his anger at the lack of work for disabled people during the final phase of the Second World War (Komatsu, 2017). The maneuvring of newspapers and journals, the use of major urban galleries, and the manipulation of psychiatric and psychological ideas of genius – these were all new elements. However, on the whole, a gradual development in presenting exhibitions of the works of the patients began in1940.

As regards the historical continuity in Japan; the information we have now is still a fragment of the historical knowledge. We need to study more and publish texts, papers, and books in English. As for the exhibition of the catalogue of “Eye, Eye, Nose, Mouth,” it is interesting to recognize both the history and current conditions. Of course, the artists have their own individuality and authenticity, but at the same time, they have used traditions, both old and new. As the editors shrewdly point out, one cannot say whether Ukai Yuichiro is drawing dinosaurs and popular anime characters or ukyo-e and yokai. What is the origin of the works of Takenaka Katsuyoshi, which look like an industrial city and medieval Gothic cathedrals at the same time? Are Li Ben’s figurated body parts a reflection of modern cruelty or historical freedom of the body? Or is Li Jie’s Cracked Egg a feminism message or the revival of Xī Yóu Jì, which started from turn of a stone egg to Sūn Wùkōng? These are less historical questions than cultural means to connect contemporary outsider art with history and innovation. Koenig, Schaffer, and many artists in Japan and China have opened several exciting ways to think about history, the present, and the future.

About the Author

Akihito Suzuki, University Professor, Keio University, Tokyo, Japan email: akihitosuzuki2.0@gmail.com, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5142-3180

1 In 2017, Tokyo Station Gallery had a major exhibition of the work of Adolf Wölfli (1864–1930), a patient who spent approximately 30 years painting at a psychiatric hospital in Bern, Switzerland. In 2013, the Wellcome Collection in London had an exhibition of “Souzou: Outside Art from Japan,” which attracted about 94,000 visitors. In 2018–2019, Paris and Tokyo co-organized “Paris–Tokyo Japonais II,” which is about contemporary art brut in Japan, at the Halle Saint Pierre Gallery, which attracted approximately 70,000 visitors.

http://www.ejrcf.or.jp/gallery/exhibition/201704_adolfwolfli.html

http://www.artbrut.jp/e_report/

https://artbrut-japonais2.themedia.jp/

References

Bailey, M. (2018). Starry night: Van Gogh at the asylum. London: White Lion Publishing.

Gilman, S. L. (1982). Seeing the insane: A cultural history of madness and art in the Western world. New York: John Wiley, in association with Brunner-Mazel.

Killen, A. (2017). Psychiatry and its visual culture in the modern era. In G. Eghigian (Ed.), Routledge history of madness and mental health (pp. 172–190). London: Routledge.

Micale, M. S. (2004). The mind of modernism: Medicine, psychology, and the cultural arts in Europe and America, 1880–1940. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Mishima, Y., & Keene, D. (2009). Five modern nōp Plays (1st Vintage International ed.). New York: Vintage International.

Nakamura, E. (2016). ‘Invisible’ war trauma in Japan: Medicine, society and military psychiatric casualties. Historia Scientiarum, 25(2), 140–160.

Nakamura, E. (2019). Psychiatrists as gatekeepers of war expenditure: Diagnosis and distribution of military pensions in Japan during the Asia-Pacific War. East Asian Science, Technology and Society, 13(1), 57–75.

Peniston, W. A., & Erber, N. (2007). Queer lives: Men’s autobiographies from nineteenth-century France. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Robertson, J. (2010). Eugenics in Japan: Sanguinous repair. In edited by A. Bashford & P. Levine (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the history of eugenics (pp. 430–448). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sasaki, K. (2019). Bioethics between imaginary and reality: Tracing science fiction and its shaping of transplant medicine protocols in Japan. East Asian Science, Technology and Society, 13(1), 77–99.

Scull, A. T. (2015). Madness in civilization: The cultural history of insanity, from the Bible to Freud, from the madhouse to modern medicine. London: Thames & Hudson.

Shorter, E. (1997). A history of psychiatry: From the era of the asylum to the age of Prozac. Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons.

Tyler, R. (1992). Japanese nō dramas. London: Penguin.

Vinitsky, I. (2017). Madness in Western literature and the arts. In G. Eghigian (Ed.), Routledge history of madness and mental health (pp. 153–171). New York: Routledge.

Yumeno, K., & Honnoré, P. (2003). Dogra magra: Roman. Paris: P. Picquier.

Japanese References

Goto, M. (2019). 後藤基行. 日本の精神科入院の歴史構造: 社会防衛・治療・社会福祉. 東京 大学出版会.

Hattori, T. (2003). 服部正. アウトサイダー・アート: 現代美術が忘れた「芸術」. 光文社.

Hattori, T. & Fujiwara, S. (2014). 服部正 and 藤原貞朗. 山下清と昭和の美術:「裸の大将」の神話を超えて. 名古屋大学出版会.

Kara, J. (1980). 唐十郎. 沼 ; ふたりの女. 漂流堂. 京都 書院.

Kinugasa, S. (1977). 衣笠貞之助. わが映画の青春: 日本映画史の一側面.中央公論社.

Komatsu, S. (2017). 小松左京. 「くだんのはは」 in Hearn, Lafcadio et al. 呪. 汐文社, 2017. 文豪ノ怪談ジュニア・セレクション / 東雅夫編.

Meishin Chosa Kyogikai. (1949). 迷信調査協議会 et al. 迷信の実態. vol. 1, 技報堂.

Ozawa, N. (2008). 小沢信男. 裸の大将一代記: 山下清の見た夢. 筑摩書房.

Watanabe, T. (2012). 渡辺保. 歌舞伎手帖. 増補版角川 出版.

Watanabe, Y. & Kobayashi, M. (2018). 渡邉芳樹 and 小林瑞恵. スウェーデンのアール・ブリュット発掘 : 日常と独学の創造価値. 平凡社.

Zeami, et. al. (2017). 世阿弥 et al. 能楽名作選: 原文・現代語訳. Kadokawa.