Choreographing Changes: Narratives of Resistance and Healing

编导变化:反抗与疗愈的故事

Sohini Chakraborty and Maya Sen

Kolkata Sanved, India

Abstract

Kolkata Sanved is a pioneering organization in the field of dance movement therapy (DMT) in India and South Asia. The organization has pioneered the use of DMT for psychosocial rehabilitation and empowerment through its model, Sampoornata. This article aims to describe the Sampoornata approach of DMT1 for psychosocial rehabilitation through a case study on its applications with a survivor of human trafficking. Globally, almost 80% of human trafficking is related to sexual exploitation, and India is the hub of these crimes in Asia. Human trafficking affects the marginalized sections of society, with women and children being the prime target. Victims of sexual trafficking suffer from severe psychological and physical trauma, and if these symptoms are not addressed, their process of recovery is hampered. The child protection system is usually unable to meet these needs, forcing survivors to carry the burden of trauma into their future. A participant of Kolkata Sanved’s program, Ruhi,2 was one such girl who encountered the system. This is her story and how she used the Sampoornata approach to get a new lease on her life.

Keywords: Dance Movement Therapy, Sampoornata, Sexual Violence, Empowerment, Social Development

摘要

Kolkata Sanved 是印度和南亚舞蹈治疗领域的领军机构。机构使用Sampoornata的治疗模式, 是治疗和强化病人心理社会层面的先驱。文章意在描述这个被称作Sampoornata的舞蹈治疗方法, 并例举它在使用于一名人口贩卖幸存者身上的实例。全球近80%的人口贩卖涉及到性奴役, 而印度是亚洲的人口贩卖的中心。人口贩卖影响着社会中的弱势群体, 而女性和孩子是主要的受害者。性奴役的受害者受到严重的精神和肉体的创伤。如果这些症状不被解决, 那么他们的治疗过程就会受到阻碍。儿童保护设施通常不能满足这些需求, 迫使幸存者把创伤的负担一直带在身上。Kolkata Sanved的参与者之一名叫Ruhi, 她就是一个经历过这个系统中的女孩。这就是她的故事以及她如何使用Sampoornata的方法开启生活的新篇章。

关键词: 舞蹈动作治疗, Sampoornata, 性暴力, 使强大, 社会发展

Overview of the Sampoornata Approach of Dance Movement Therapy

In dance movement therapy (DMT), healing and transformation of an individual happens through the creative process and effort. In this creative process, an individual engages in a multidimensional experience. This is one of the primary factors that guide the pathways for growth in the process. Naturally, dance integrates the whole body and mind. This holistic approach includes the physiological, cognitive, emotional, and sociocultural aspects of human beings. The process co-creates the space where both the practitioner and the participant contribute dance movement, which is a nonverbal process. This is followed by verbal articulation, leading to the gradual evolution of the therapeutic relationship. There are three key stages of DMT practice in the Sampoornata process that intersperse and seamlessly lead from one to another. These are healing, empowerment, and transformation. These stages are drawn from and adapted from global DMT practice and are further expanded to meet the needs in the local context. The process of Sampoornata brings out psychosocial elements that are inner and interpersonal. The model adopts the four core principles of global DMT practice—DMT as a creative methodology, body-based method beyond the hegemony of verbal creation and experiential methodology—and paved its own way to emerge into a new model. The model focuses on body, self, well-being, and life. In the process, it works on four areas of the self—physical, emotional, cognitive, and social. The curriculum of the model was inspired by spontaneous movement of individuals, improvisation, therapeutic elements of Indian dance forms, and Navanritya.3 Sampoornata uses footsteps, hand gestures, shape, Navarasa4, group dance, folk dance, and healing touch. The “healing touch” is an important component that Sampoornata has integrated in its curriculum. This is taken from the local culture and adopted in a therapeutic manner, in which, after the completion of the process, the practitioner places their hands on the heads of each participant and provides a healing touch. Music is an integral part of the process (Chakraborty, 2019).

The Sampoornata process comprises of the following components:

- Assessment

- Development of a plan of implementation

- DMT session, including the following: opening ritual, warm-up, needs-based therapeutic process, activity focused on trauma release, relaxation, healing touch, fun/free dance (if required), closing ritual, group discussion, feedback, and reflection, debriefing

- Documentation of the process

- Evaluation

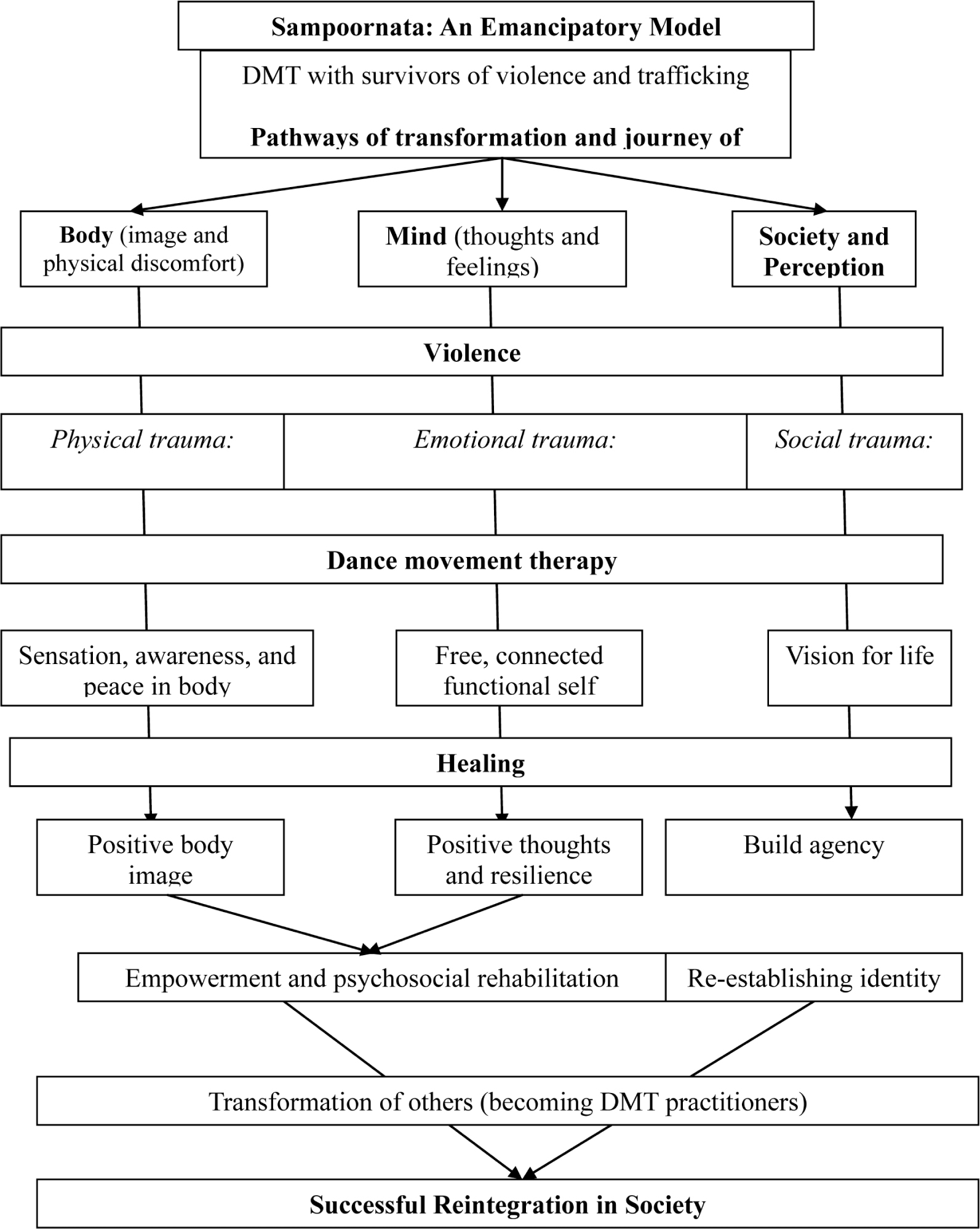

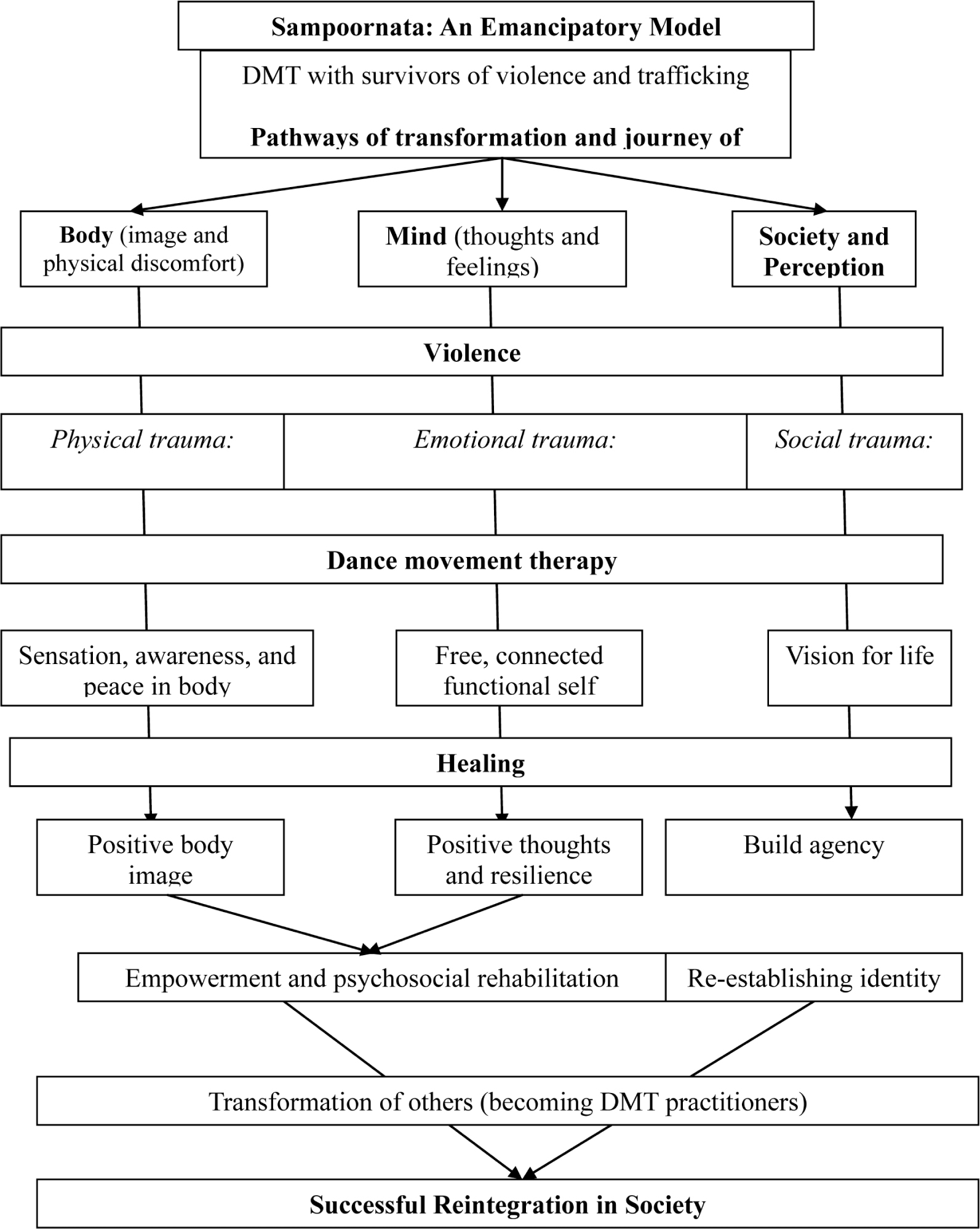

Figure 1 shows a diagram of how one gains empowerment through the process of Sampoornata and is successfully reintegrated into society.

FIGURE 1 | This diagram is based on qualitative data collected from survivors of violence and human trafficking. It demonstrates the effectiveness of the Sampoornata approach of DMT in enabling survivors overcome trauma caused by violence at the physical, emotional, cognitive, and societal levels.

In Ruhi’s case study, we will be observing how this approach and process helped her to heal, empower, and transform. Ruhi was one of the participants in Kolkata Sanved’s anti-trafficking program. The journey through the module with her facilitator Karishma led to major transformations in her life. Her case study aims to illustrate how Sampoornata can be effective for trauma recovery. Presented below is an account of her journey.

Early Life of Ruhi

Growing Up

Ruhi was born in Dhaka, the capital city of Bangladesh. She spent her early years in the city. What she remembers most of her time there was her relationship with her mother. Her mother, a strong woman, stood up for her and made sure her daughter got the chances she was not fortunate enough to get. As a result, she made sure her daughter got the education she deserved. Her entire day was planned out. After she came back from school and finished her homework, she went straight for karate training. She had little free time. She would stay at home and not go out. One day, her mother saw her being sexually harassed. After that, her mother forbade her from going out. She was upset that her daughter could not fight back. Rebellious by nature, Ruhi began to feel more and more restricted at home, and in a burst of adolescent angst, she ran away from home after being denied a cell phone.

Arrival in India

Ruhi came to India at a young age of 14 years. Initially, she had come to Kolkata. Over here, she met a woman named Anuja, who showed her love and affection. She reminded her of her mother. Confused and alone, Ruhi welcomed the familiarity. She confided in her that she had left home on bad terms. Anuja lived in Bangalore. She asked Ruhi to come to Bangalore with her. With high hopes, Ruhi went along. To Ruhi’s utter dismay, Anuja had sold her to a brothel. Ruhi was heartbroken. When she came to India, she did not know that girls were used like this.

In Captivity

The border between Kolkata and Bangladesh is where a lot of trafficking takes place. Scores of women and young girls are taken in loaded trucks and given false identity proof. There is a nexus controlling the process throughout the country with full knowledge of law enforcement officials (Deb, Srivastava, Chatterjee, & Chakraborty, 2005; Joffres et al., 2008). Ruhi also received false identity proof. Millions are trafficked from all over the country. A large number of individuals are trafficked from the bordering states of Nepal and Bangladesh (Ghosh, 2009). Ruhi was trafficked from Kolkata to Mumbai.

Those caught behind the four walls of the brothels suffer unimaginable horrors. Ruhi recounts her daunting experiences. When she first arrived, they told her many cruel and dirty things. They would speak to her in Marathi, laughing at her inability to understand. She was very confused. She tried to run away many times, but they caught her and beat her. The man who had sold her used threats and brute force to keep her in line. She could not stand up to him. Often, he would charge at the girls wielding a knife. He had kept some people in the brothel to make sure the girls do not run away. They were all very afraid of them. They were often inappropriate with the girls. These boys would drink and become violent. They lay under her bed to make sure she did not escape. The owners of the brothel were very cruel. They would force these girls to give them money. According to Ruhi, “[even] if we refused, they were willing to touch us anywhere.” When she had a client, she had to travel long hours on lonely roads. She felt extremely frightened. On completing assignments, they would receive marks on their hand with ink. If a customer paid a large amount, they would receive a star. The pimps would check on how many marks or stars they got. The girls tried to pool money together so that they could run away. They tried to save scraps of money for themselves.

Rescue of Ruhi

They did not think she would run away, as she did not know the route. She was also very compliant. The NGO worker who rescued her approached her and asked whether she wanted to work. It was a day she remembers well: “He spoke to me in Marathi; angry, I abused him in Bengali. I didn’t know the person understood Bengali. He answered back in perfect Bengali. I started crying and asked for an apology.” The brothel owner caught them and told him he had to pay if he was talking to one of his girls. He said he would. He gave him 300 rupees, and they were allowed to continue. He asked her why she was there. She replied that it was because she was sold by someone she trusted and that she did not want to be there. He said he could help her and asked her that to be ready by 12. He would give the owner alcohol and rescue her while he was passed out. The only other obstacle was the brothel guards who slept under her bed. The NGO worker said he would take care of them. He promised to talk to his boss about her, and he delivered. She had been working since 2014 in the brothel. She was rescued in 2015.

The Vortex of Trauma

Her captivity severely affected her mental health. Trauma crippled her and she started losing touch with the world: “There was one day I slept with a boy for just 300 rupees! 300 rupees is worth nothing but I gave up so much for it. I was going down a bad path. Still I didn’t feel I was doing something wrong. After sleeping with customers, I didn’t feel like I was human. I had to pinch myself to make sure I was alive.” She saw others around her and felt they could leave when they wanted to, but she was stuck, she was in too deep. She wondered why the others did not leave. Many would come and ask her if she did this work because she enjoys it. How could she explain her plight to them? “I lived my life through laughter and tears, but there was an underlying sense of hurt behind all that. I could never really express it. Other people think I am happy. They don’t know the pain and struggle that has gone into being where I am today.” She lost faith in everything around her. She was forced into this life after being betrayed by someone she loved. She talks of how much she trusted Anuja. She would not have trusted Anuja had she been a man. Because of the betrayal, her heart was broken. She was scared about what would happen to her. She wondered how she could go home. She wondered how she would be judged by others. She would cry herself to sleep. Every day, she underwent threat and fear in the brothel. She started losing trust even further. The marks they left are still on her body. They would starve her as well.

Finally, she alienated herself from everything. To keep herself alive, this was the only way. She felt it would not make much of a difference if she died. She begged god not to let this destiny befall on anyone else. At times she feels sad, and she cries even today. She stays awake thinking about all these. If anyone touches her at night, she gets scared and gets up. She still has nightmares, “I was like a tissue, a piece of paper, used and disposed. Everyone wanted a piece of us but no one wanted to help us. These people would do anything for 300 rupees.”

Introduction to Dance Movement Therapy: The Sampoornata Approach

After being rescued, she came to a government-run home for girls like her. Her life in the home followed a strict routine. The children wake up at 6 in the morning. They have to bathe in cold water, as that is all that is available. After freshening up, they go to do their daily chores. After that, they pack their bags, and by 8 o’ clock, they go for training. Then, they go for their prayers. Their teachers come to teach them various subjects. The girls are engaged in various forms of training. Although monotonous, Ruhi was glad she had escaped the brothel. However, she still carried her trauma with her and it resurfaces from time to time. Curiously, things started to change after she met Karishma from Kolkata Sanved.

Hesitation and Reluctance

Karishma would conduct classes in the shelter home, and Ruhi was selected for these classes. At first, she did not really know what these classes were about. It seemed to be a dance class of sorts. Later, she learned that the sessions were for DMT. When she first started DMT, she did not take it seriously. She would sit in a corner and laugh at the trainers: “I said these didi’s are mad and they would make us mad. But actually it was difficult to go into DMT. You need focus and concentration. You need to be able to go into deep work. I didn’t want to. Therefore I took it frivolously.” Later, she made an effort to focus and found herself getting more involved in the process. The practitioner supported her and tried to draw her in. DMT is practiced in a group. She says, “DMT helps heal your body in a different way. If your body hurts, you can take medicine. However some scars are not just physical.”

Self-Regulation

DMT helped the participants with self-regulation. They were able to control their emotions and cognitions. They learned how to put their experiences into perspective. They learned focus and concentration. They channeled their anger and frustration into something positive. Cognitive self-regulation in turn enhanced their ability to control emotions. Initially, they would come to classes crying. Even while doing relaxation, they would cry. The DMT practitioners never asked them why they cried. DMT helped them think. Slowly, they started identifying the reasons for their pain. They wanted to work on releasing their anger. Ruhi felt that there was an anger in her that made her doubt all individuals. DMT helped her learn what to do with this anger. Many girls would self-harm in the shelter home. They were taught that they were at fault. DMT helped them realize the fault remained with those who hurt them, which was the reason why should they hurt themselves. Their lives were just beginning. They learned about their strength and power. Ruhi says relaxation was where she first learned to regulate her emotions. DMT helped participants release negative emotions.

Learning New Skills and Discovering Own Potentials

DMT helped Ruhi learn new skills and discover her potentials. She says, “Four girls are going to be restored within a month, hence they will have a chance to go back. One of the girls plans on going back home and practicing the skills she learnt here. She wants to conduct DMT sessions.” Ruhi too was able to become a practitioner. She wants to go back to Bangladesh and practice. “I got a lot of things by coming here, which I would not get elsewhere. To get something you need to go through tough times. I fell very low but I got to be a DMT practitioner through this. I felt happy I could become something. I like learning new things. I have got that here. I made a mistake. Now I feel so happy that I can help other people move forward.”

The identification of potential is especially important for these girls, as it gives them access to a means of livelihood. Being able to achieve dreams is an important part of recovery from trauma, and often, girls such traumatic experiences do not have access to options. DMT, in the form of Sampoornata, can fill that gap by offering customized training programs to survivors, so that they can realize their potential.

Training in Sampoornata includes likening the process of healing to a journey—a journey from being a “survivor” to a “healer.” The training in Sampoornata combines the five key components of movement vocabulary, body training, process of personal transformation, self-care practice, facilitation skills, and reaching out to community. Of course, the most important one is the process involved in facilitating a DMT session in the community. The theories on human rights, social development, and mental health are integrated in the training program. Sampoornata has also been introduced in a formal academic setup as a diploma program with a deemed university in Mumbai. The training on becoming a practitioner takes one year. However, when a survivor joins the program to become a practitioner, it takes longer, at least two to three years. The training for survivors first focuses on personal healing and experiential learning and then moves to theoretical learning. The training to become a practitioner is very rigorous in Sampoornata (Chakraborty, 2019).

Social Support

DMT helps create essential support systems. Traditional support systems often fail survivors of trauma; thus, creating alternate forms of support are a priority. At one level, the therapeutic relationship between the DMT practitioners and participant creates an atmosphere of support. Ruhi feels that she and Karishma have a special bond. Karishma is a DMT facilitator and a friend. The DMT practitioner’s role in Sampoornata is vital. As it is a group model and can be applied in large communities, two practitioners work together for each setting. Integrity, simplicity, and “therapeutic presence” are three aspects of facilitating the Sampoornata process. “Therapeutic presence” means constantly being present to the need of the group. Therapeutic presence includes nonjudgmental body language, attitude, and practice of empathy. A nonverbal facilitation style is important, with which the space is held (Chakraborty, 2019).

Sampoornata lays down the conditions for the effective development of the therapeutic relationship; as a result, she was able to share many things with Karishma. She shared important parts of her past. The sharing section of DMT helped her connect with herself. She started realizing that this is very necessary for her. Ruhi was extremely trusting in her childhood when she arrived in India. Through DMT she has now learned about boundaries and trust. Sometimes one should be wary of even the closest relatives. She wants young, impressionable girls to know this. Many children’s own mothers have sold them. The practitioners taught them about the good touch and bad touch. She learned to be careful of those who are dangerous. “There are many girls who come into the child protection system. They are so sad they cry all the time. DMT helps them stabilize and open up.”

Peer bonding was another area that DMT enabled for Ruhi and her peers. Peer bonding is especially important for residents of a shelter home. Such support can enhance the experience of institutional living. Karishma helped them with conflict resolution. Through DMT, she learned how to regain connection with the outside world: “I was stuck within myself, DMT helped me come out and face the outside world.”

One of the ways in which Sampoornata enabled bonding among participants is through its emphasis on a group-based approach for healing. In Sampoornata, the group is the space for healing. This model strongly believes in the group process and is practiced within group settings. The group setting is extremely beneficial for the process of healing, as there are multiple resources in that space, and thus, participants do not need to rely solely on the practitioner. This also deconstructs the notion of expertise, as it is based on the assumption that the practitioner does not have all the knowledge. The group process starts and ends with a circle. In the circle, sharing of pain, joy, experiences, personal reflections, love, care, and support from each one helps the group to grow as a healing community. Two important things in Sampoornata group process are witnessing and experiencing the constant balance between working with minds and bodies in the group. The model allows for bringing attention to the transition between these two things and the group member’s responses to one or the other (Chakraborty, 2019).

Empowerment

DMT has empowered Ruhi. It has taught her to love herself, even the parts that are difficult to love. It has taught her to fight the stigma. She no longer feels ashamed to share her story. It empowers her. She has accepted her mistakes and made up for them. She wants other girls to learn from mistakes. Bad situations can destroy an individual or make him or her stronger. She chooses to do the latter. “There are many people who will try to bring you down. Like the stormy wind they bring destruction to your life, it is up to you to rise above it,” said Ruhi. Now she no longer looks down in shame and guilt, she looks in the eye and reiterates that she is not at fault, she is not bad, and she is respectable. She will go far in life and achieve her dreams. She now resists the stigma forced on her because of her gender. DMT taught her not to fear judgment from society. It helped her realize the world is as much a place for boys as it is for girls. She learned that just because she is a girl does not mean she is weaker. It gave her the skills and confidence necessary to speak up. Earlier, Ruhi was afraid to talk to outsiders. She was afraid of the judge and the courtroom she had to face. The facilitators co-create a space for her through the process on how to be brave. In DMT, she did a session on eye contact. This builds both physical and emotional confidence to overcome her fear of the courtroom and the judiciary system. She practiced the courtroom process though dance and movement, and the entire group helped her in this experiential rehearsal process. She found that verbalizing and voicing her thoughts and rights are extremely helpful. There was a presentation where the girls in the shelter home were hesitant to speak up, but those in the DMT session could speak up with ease. She was a speaker for the event. Those who heard her wished their children would be able to speak like her. Even though she spoke in front of important people, she held her own. She looked them in the eye and said what she had to say. Those who had known her from the beginning were amazed at her progress. She, who was nervous and was biting her nails, was now giving lectures. She was told she would go far. She said it was nothing out of the ordinary and that she had the right to speak. They were amazed that she had learned to speak about her rights.

Ruhi’s ability to speak up helped her get all her perpetrators convicted.

The Sampoornata approach of DMT is a space for fighting hardships and resisting life’s challenges. Thus, personal empowerment is a major goal in Sampoornata approach. Working on the self is central to the process of empowerment. DMT teaches participants self-acceptance, it teaches participants to give priority to oneself; this in turn helps them to change their circumstances. It empowers individuals to strengthen themselves. Those who lose all hope are able to find hope again. Through the Sampoornata approach of DMT, life’s connections become clear and so do one’s goals. Empowerment of a DMT practitioner is integrated into the process of healing (Chakraborty, 2019).

Looking Toward the Future

Ruhi no longer lets outsiders control her life. She has many things she wants to do. She wants to go back to school. She wants to become a professional DMT practitioner and help others. She also wants to work in education. She wants to free all the girls who are stuck like she was. She hopes her story will inspire others: “I wanted to write a book on my story, it was my dream, I wanted people to learn from my life and mistakes.” Ruhi has had a long and tumultuous journey, but in the end, she has emerged victorious. Her tremendous strength and ability have helped her navigate adverse life experiences. The Sampoornata approach of DMT helped her facilitate her healing process.

Sampoornata is an emerging model (Figure 1). The model is flexible in structure, culture-specific, and adaptable. Flexibility allows the DMT practitioner to address the real needs of the group. The rights perspective is very strong in this model. This model consciously calls its clients as “participants” and a therapist as a “practitioner.” Knowledge and understanding of the development approach are gained by the practitioners through the rights perspectives and working with the marginalized communities. Sampoornata addresses the needs of the individual in their context. The model also addresses the issue of economic empowerment of the participants. The model focuses on strengths-based psychological intervention that supports individuals to identify positive aspects of life and reinforce them for optimal psychological health and well-being. Sampoornata is nonclinical and is not used as a diagnostic tool or as a mode of treatment. The model moves beyond DMT. As a country, India has larger sections of people who are facing marginalization and reaching out to them is very important. This requires an approach that is community-focused. The model provides DMT to those who face vulnerability and marginalization. Sampoornata demonstrates a new way of integrating the existing principles of DMT and adds new dimensions to it and moving toward an emancipatory model (Chakraborty, 2019).

Acknowledgment

We thank dance movement therapy practitioner Shalaka Sisodia for helping us in the data collection. She is a committed practitioner of Kolkata Sanved. We also thank Kamonohashi Project, Japan, for supporting the implementation of our anti-trafficking project. Their support has enabled us to touch the lives of many survivors. We also appreciate the Kolkata Sanved team for their tireless effort in all our endeavors.

About the Authors

Dr. Sohini Chakraborty, an Ashoka fellow, sociologist, dance activist, and dance movement therapist, is the founder-director of Kolkata Sanved. For more than 22 years, Sohini experimented with breaking the barriers of traditional dance and introduced dance movement therapy as a tool for psychosocial rehabilitation to provide a fresh approach to rehabilitation in South Asia. This unique and innovative methodology was developed by Kolkata Sanved under the leadership of Sohini Chakraborty. Honed over the past two decades, Kolkata Sanved’s Sampoornata’ model is a pioneering concept in South Asia. She has been felicitated by the Department of Women and Child Development and the Department of Social Welfare of the government of West Bengal in 2016. She received the prestigious True Legend Award in 2015 and the Diane von Furstenberg Award in 2011 for transforming the lives of other women. She also received the Newsmaker 2012 Award by Zee 24 Ghanta, the leading news channel of West Bengal, for outstanding achievement and inspiration.

Maya Sen works at Kolkata Sanved as an assistant program manager. She is also a narrative therapist whose approach to mental health work aims to bridge the gap among mental health services, social work, and social justice activism. She works primarily in the context of child and adolescent mental health.

1 Sampoornata: An Emancipatory Model

2 The Sampoornata approach of DMT described here was based on Sohini Chakraborty’s doctoral thesis.

3 All names were changed to protect confidentiality.

4 Navarasa is a combination of nine emotions used in classical Indian performing arts.

References

Chakraborty, S. (2019). Transforming lives through dance movement therapy. Doctoral thesis mimeo, Tata Institute of Social Sciences Mumbai, India.

Deb, S., Srivastava, N., Chatterjee, P., & Chakraborty, T. (2005). Processes of child trafficking in West Bengal: A qualitative study. Social Change, 35(2),112–123.

Ghosh, B. (2009). Trafficking in women and children in India: Nature, dimensions and strategies for prevention. The International Journal of Human Rights, 13(5),716–738.

Joffres, C., Mills, E., Joffres, M., Khanna, T., Walia, H., & Grund, D. (2008). Sexual slavery without borders: Trafficking for commercial sexual exploitation in India. International Journal for Equity in Health, 7(1),22.

Kolkata Sanved. (2017a). Empowering lives through dance movement therapy. Retrieved from http://kolkatasanved.org/what-we-do/.

Kolkata Sanved. (2017b). Sampoornata. Retrieved from http://kolkatasanved.org/what-we-do/.