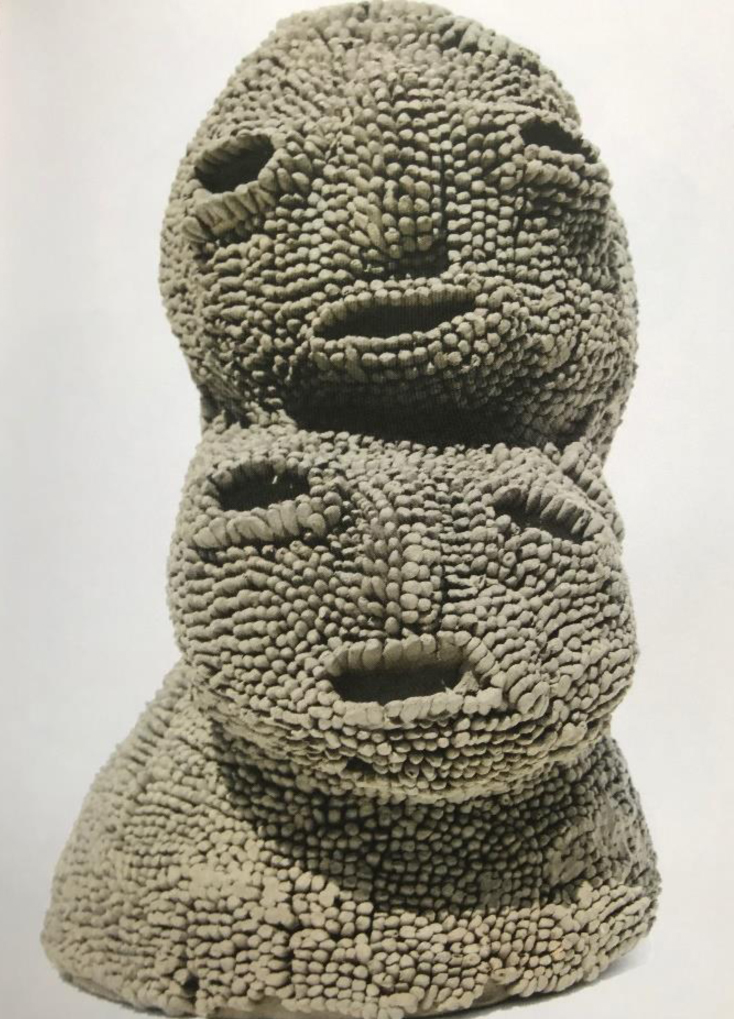

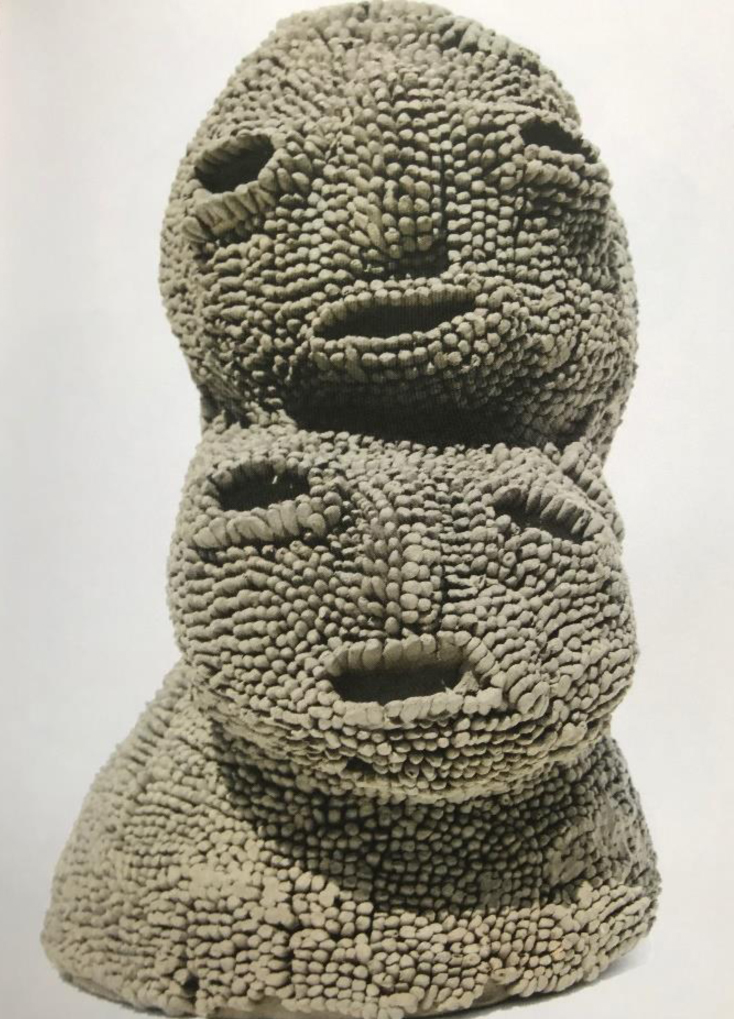

Kamae Kazumi, Masato Appearing in My Dream, Fired clay, 32 × 20 × 20 cm, 2015/ Atelier Yamanami.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2019) 5(1):14–24 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2019/5/3 |

An Interview with Raphael Koenig and Benny Shaffer: Expanding Normality at the Edges of the Art World in China and Japan

Raphael Koenig和Benny Shaffer访谈:在中国和日本的艺术世界边缘扩大常态

Lesley University, Cambridge, MA, USA

Abstract

This is an in-depth interview with Raphael Koenig and Benny Shaffer exploring the development, goals, and outcomes of the 2019 exhibition and symposium at the Harvard University Asia entitled Eye Eye Nose Mouth: Art, Disability, and Mental Illness in Nanjing, China and Shiga-Ken, Japan.

Keywords: artistic advocacy, stigma, disability, mental health, self-taught artists, outsider art, art brut, Nanjing Outsider Art Studio, Atelier Yamanami, Guo Haiping, Masato Yamashita

摘要

深入访谈拉斐尔•科尼格(Raphael Koenig)和本尼•沙弗(Benny Shaffer),探讨2019年由哈佛大学亚洲中心在中国南京和日本Shiga-Ken举办的名为“眼眼鼻嘴:艺术,残疾和精神疾病”的展览和研讨会的发展、目标和成果。

关键词: 艺术宣传, 耻辱, 残疾, 心理健康, 自学成才, 艺术家, 艺术家, 南京外来艺术工作室, 山中工作室, 郭海平, 山下雅人

Shaun McNiff (SM): Please tell us how you both came to exploring the art workshops in China and Japan; how you started to cooperate? How did the 2019 Harvard Asia Center exhibition originate and develop? What were your goals? Were there challenges? Are there particular people and institutions who helped make it possible?

Raphael Koenig: As we are working in the fields of Anthropology and Comparative Literature, respectively, it is very important for both of us to be able to exchange ideas with scholars who work specifically on issues related to the theory and practice of art therapy: so we are really grateful for your sustained interest in our exhibition.

Benny and I are both interested in exploring the margins of art, literature, and cinema, and focusing on lesser-known figures, movements, and phenomena that we feel are worthwhile: Benny is currently finishing his dissertation in Anthropology on the “edges” of the art world and entertainment industry in China, and I defended my dissertation in Comparative Literature, with a strong art historical component, on the relationship between the historical avant-gardes and self-taught art from the 1920s to the 1940s.

So, this project felt like a natural way of combining our respective approaches: I have been working on historical self-taught art, but was interested in looking into the innovative contemporary approaches developed by these specific art workshops. Benny has lots of experience conducting anthropological fieldwork, which involves engaging with local communities and participating in their daily routines while attempting not to disrupt them.

We felt that what was often missing in the description of art workshops for people with disabilities, and probably of self-taught artistic expression in general, was a more rigorous attention to their individual socio-historical contexts: bringing the conceptual and practical toolbox of anthropological fieldwork into a project that is informed by more theoretical discussions on self-taught art and is concerned with questions of artistic expression, creativity, disability, and individual agency felt like the right way to go. We hoped to shift the discourses on these workshops.

Kamae Kazumi, Masato Appearing in My Dream, Fired clay, 32 × 20 × 20 cm, 2015/ Atelier Yamanami.

The challenges were many. On a practical level, we had to figure out the logistics of shipping works across continents and coordinating with guests from China and Japan to bring them all together for the opening and symposium. But also, on a more fundamental level, this is by no means an easy topic. How does one exhibit or talk about these works while trying to navigate the multiple ethical minefields that have to do with possible cultural appropriation of East Asian art or art produced by people with disabilities? That is why it was important for us to provide as much context as possible in the exhibition itself and the catalogue.

We are very grateful to Professor Karen Thornber, Director of the Harvard University Asia Center, who supported our project from the start. She is involved in groundbreaking work on medical humanities in East Asia, and was interested in displaying visual works produced by people with disabilities in China and Japan at the Asia Center.

We are also grateful to Masato Yamashita, Director of Atelier Yamanami, and Guo Haiping, Director of Nanjing Outsider Art Studio, for their warm welcome and incredible help throughout the project: they really supported our endeavor from the start, and went above and beyond to make sure that our stay at their workshops was as productive and enriching as possible.

And we owe a huge debt of gratitude to the artists and staff of each workshop, who openly welcomed us into their communities, were incredibly generous with their time, and allowed us to be part of their lives and to document and share their work with international audiences.

Yukiko Koide, a Tokyo-based gallerist who is also a leading expert on Japanese self-taught art, supported us every step of the way: from first email introductions to the practicalities of shipping valuable works from Japan for our show, and as an interlocutor in helping us figure out the Japanese side of the equation.

SM: How would you compare the work that you have observed in China and Japan? Your catalogue emphasizes the cultural context of each artist’s work as well as the particular orientations of the workshops that support them. Daniel Wojcik shares your concerns about how these individual artists work with and in relation to the values and structures of their particular communities and contribute to them. He feels that this feature has not been sufficiently addressed in the history of self-trained artists dealing with various disabilities and health challenges. While their artistic expressions may manifest qualities that are shared with others throughout the world, they are nevertheless fundamentally working within specific places and historical circumstances like any other artist and not to be grouped into an “outsider” category or “population” which diminished their distinct personhood and artistic accomplishments. You also emphasize these points in the exhibition catalogue.

Raphael Koenig: We absolutely agree with Daniel Wojcik on this point. In fact, my own research has been dedicated to showing that “outsider art” or “art brut” are categories that tell us relatively little about the provenance or meaning of these works. For instance, what relationship would there be between works created in the context of a care institution (psychiatric care facility, workshop for people with disabilities, etc.), within a purely independent self-taught practice (such as the Watts Towers in LA), or as part of a religious or para-religious experience (for instance, the drawings of Czech psychic Anna Zemánková)? These works were mostly lumped together in one category that only makes sense if we take into account the specific agendas and aesthetic sensibilities of people like Jean Dubuffet, who in the immediate postwar period were attempting to define a “primeval” locus of artistic expression. The institutional clout of foundations and museums that perpetuate his legacy aside, there is no compelling reason why we should rely on his theories. Works by self-taught artists often seem to be used to support the validity of Dubuffet’s claims, as mere illustrations in a sense. But critical discourses should arguably be made to serve the artworks and allow for a better understanding of them, not the other way around. Works produced in art workshops for people with disabilities in China and Japan have been exhibited internationally in the past (most notably at the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne and at the Halle Saint Pierre in Paris), but generally there seems to have been little engagement with the concrete reality of these workshops: How do they operate? How are they perceived in their respective societies? Do they themselves defend a broader agenda of social change and heightened integration of people with disabilities within the rest of society?

All of these are questions that we find extremely relevant, but unfortunately in many of the Western institutions that exhibited these works, a lack of proper research on these workshops led to generalizations, for instance, focusing on the neo-romantic cliché of the isolated “brut” artist.

The works we featured in the show undoubtedly display strong individual features, idiosyncratic techniques, and so on, but one should not underestimate the importance of the fact that they were made possible by a collective structure (namely the workshop) meant to empower artists with disabilities. There is nothing wrong with being part of a collective; saying that a late nineteenth century painter was part of a group that was based in Pont-Aven, Brittany, or in the Hudson River Valley does not diminish their individual achievements. It is meaningful context. There is no reason to treat self-taught artists any differently.

SM: Are their qualities shared by both workshops? Common features in both the missions of the workshops and the art that is generated?

Benny Shaffer: I’d say the strongest parallels between the workshops are in their overarching missions, which can be seen in their philosophies of non-intervention; they don’t provide specific artistic training or formal instruction for the participants, and don’t intervene in the creative process. Instead, they provide an open space for free experimentation that allows the participants to develop their own distinct artistic practices and styles at their own pace. At the workshops in China and Japan, we were both struck by the extremely distinctive, and in many cases radically different approaches that the individual artists took in their practices. This came as a surprise because they often work in close proximity to one another over many years. While the participants of both workshops engage with one another in different ways in their communities, and the workshops create a space for social connection and shared experience, the individual experiences of all the participants vary dramatically.

SM: The exhibition was unique in that in addition to showing the art from the workshops in China and Japan, it also included a symposium involving scholars from Harvard and other institutions who explored the current state of disability and mental health services in China and Japan from the perspectives of law, anthropology, disability, and health services. Attention was given to the ways that the societies deal with stigma in families and communities. In the symposium there was unanimity with regard to how the art workshops can not only help the individual participants with the daily challenges they face, but also how they might further better understanding of people living with disabilities within the various communities and regions of China and Japan.

Benny Shaffer: We wanted to engage a broad, interdisciplinary community of scholars and art practitioners, so it was essential for the exhibition to also have an academic symposium. We began planning this part of the exhibition-related events from the beginning. In Karen Thornber’s introduction to the symposium, she spoke to the urgency to support more scholarship on questions of disability and mental health, and to offer deeper insights into the scope and extent of these issues in East Asia. Raphael and I then talked about how it was crucial for us to contextualize and consider the social, cultural, and political dimensions of the workshops’ activities, and also show a clear focus on the processes and conditions of production at both art workshops.

Guo Haiping and Masato Yamashita then shared with us the history, guiding principles, daily practices, and future plans of their respective workshops. As I mentioned before, they both insisted on how they do not intervene in the creative processes of the artists and pointed out, based on their years of experience, how these artistic practices noticeably improved the quality of life of the people in the workshops, and helped fight widespread stigma toward people with mental disabilities and mental illness in their respective societies. The second panel focused more specifically on the social and legal issues associated with disability and mental illness in China and Japan. The first two speakers, William Alford (Director, Harvard Law School Project on Disability and Professor of Law) and Cui Fengming (Director, China Program, Harvard Law School Project on Disability, and Professor, Renmin University of China Law School), presented the work of the Harvard Law School Project on Disability, which works to improve the concrete living conditions of people with disabilities by working with and improving upon existing legal frameworks. Their work tackles legal issues to fight discrimination and unequal access to employment and education. Professor Cui offered the striking example of the Chinese college entrance exam (gaokao), which until recently did not provide any way to accommodate the needs of people with major visual impairment. The following speaker, Andrew Campana, began his talk with a bilingual performance of poems by one of the Japanese artists in the show, Ukai Yuichiro.

He also shared interdisciplinary insights into how activists for the rights of people with disabilities have produced artworks in a variety of media, ranging from poetry to performance, to make their voices heard in Japanese society. Finally, Arthur Kleinman (Professor of Anthropology, Professor of Medical Anthropology in Global Health and Social Medicine, and Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard University), reflected on his ethnographic fieldwork on mental health in China over the past three decades and the changing conditions. On the following day Raphael gave a presentation at the Harvard Art Museums’ Art Study Center on works from the collection related to mental health and self-taught art.

Ukai Yuichiro, Obake (cropped), Felt tip pen, colored pencil and ink on cardboard, 73.5 × 82.5 cm, 2017.

SM: When we were discussing common qualities of art healing in the symposium, I was impressed by William Alford’s complementary statement that “stigma is also universal.” Europe and more recently North America, have considerable histories in recognizing and appreciating the expressions of self-taught artists and people living with disabilities. The challenges related to furthering human understanding and dignity are still significant, but greatly supported by your documentation of East Asian initiatives.

Raphael Koenig: What we tried to show in our catalogue essay is that there is, in fact, a substantial history of engagement with these topics in Japan. There is still a lot to be done on this, but the pioneering research of Akihito Suzuki (who offered a helpful summary of this in an article he published in the Routledge History of Madness and Mental Health in 2017) showed that psychiatric hospitals in Japan, for instance, were carefully collecting and preserving the written and visual productions of their patients from the beginning of the twentieth century. This is not a specifically Japanese phenomenon but very much part of a global trend, as many Japanese medical doctors were trained in Germany: their focus on the patient’s self-descriptions (Selbstbeschreibung) is thus based on the theories of Kraepelin and Bleuler, who were also major references for Hans Prinzhorn, the author of The Artistry of the Mentally Ill which was originally published in 1922 (Prinzhorn, 1972).

As Suzuki demonstrates, this had an impact on Japanese modernist writers, for instance, Yumeno Kyusaku. In China, modernist writer Lu Xün, who had received medical training in Japan, published A Madman’s Diary in 1918. But it is true to say that while art workshops for people with disabilities have had a strong presence in Japan (and particularly in the Kansai region) since the immediate postwar period, there is demonstrably a general penury of adequate psychiatric care facilities in China. Artists like the filmmaker Wang Bing (Til Madness Do Us Part, 2013) or Ma Li (Inmates, 2017) have seized upon this topic to denounce this state of affairs. We found it particularly significant that Guo Haiping is part of this tradition: he was active as a performance artist from the late 1980s onwards. He became aware of the fact that care facilities for people with mental disabilities or mental illness were dramatically lacking in China, and he decided to step in and create his workshop as a safe haven and a platform for artistic expression. This is also, to a certain extent, a global phenomenon: artists being the first ones to identify major social issues and to attempt to address them and offer solutions on their own terms.

To go back to the question of East Asian specificities, we found that precise attention to social and historical contexts was helpful. It proved to be a productive line of inquiry to look into the relationships between each workshop and the local governmental agencies they have to interact with, for instance. It helps us understand how these rather utopian structures are allowed to exist and develop in their respective contexts: Guo’s workshop, for instance, is nothing short of miraculous, being the only art workshop for people with mental disabilities and mental illness in existence in mainland China, so, to put it in more dramatic terms, the only institution of its kind for a population of more than 1.4 billion people.

SM: It is interesting how this journal’s featuring of the contributions of Guo Haiping in Nanjing serendipitously overlapped with the build-up for your exhibition. The Atelier Yamanami workshop in Japan is new to our readers. How is it similar to Guo’s workshop in Nanjing and perhaps different?

Raphael Koenig: As Benny mentioned, the key element that is common to both workshops, and that in fact made us decide to feature them alongside each other in the show, is their general philosophy of empowerment through non-intervention. They make it a point to offer a supportive environment, provide art supplies, etc., but never try to influence the themes, style, or technique of the works that are produced within the workshop. And this type of method does yield impressive results, a selection of which we displayed in our show.

The main differences between Nanjing Outsider Art Studio and Atelier Yamanami have to do with the respective sizes of these structures and their sources of funding. Atelier Yamanami is part of a vast network of NGOs, which was set up as a partial answer to the 1960s protest movements in Japan: local and federal government agencies decided to encourage initiatives aiming at addressing environmental issues, welfare, advocacy for people with disabilities, etc. As a result, Atelier Yamanami, which was set up more than thirty years ago, is a fairly large structure with considerable resources: even though the workshop operates in a very rural area outside of Kyoto, they have large facilities, accommodation for artists, even a fleet of minibuses and vans for transportation. Atelier Yamanami is also planning a large expansion project: they are getting a new building, with large studio rooms for artists and a visitors’ center. Conversely, in mainland China, local and federal government agencies do not routinely encourage and sponsor NGOs. Even though Guo Haiping has managed to secure support from Nanjing municipal authorities, his workshop’s funding structure is still rather precarious: the workshop has only existed for a couple of years, and it can only accommodate a relatively limited number of artists. The rooms they occupy in local community centers are fairly small: they are right in the middle of bustling urban areas, so space is tight and they cannot offer amenities such as accommodation for artists or large studio spaces.

Nanjing Outsider Art Studio, 2018 (photo by Raphael Koenig).

It should also be mentioned that it does take time for artists to develop their own styles and techniques: some of the artists of Atelier Yamanami feel much more “mature” in a way, simply because they have been allowed to develop their own practice at their own pace, sometimes over several decades. At Nanjing Outsider Art Studio, the majority of artists are quite young, they have been visiting the studio for no more than two or three years, and some of them are still in the process of finding their own styles: Niu Niu or Sun Yue, for instance, started creating radically new drawings shortly after our exhibition took place. Other artists started experimenting with clay a couple of weeks ago. These are all very exciting developments, and we would love to include such new productions in later iterations of our exhibition.

SM: It is important to note your ability to speak Mandarin and Japanese in relation to the outcomes of this work. Are there aspects of the artistic expressions that transcend spoken language both in terms of engaging the workshops on site in China and Japan and also in relation to how people in the United States responded to your Harvard exhibition?

Benny Shaffer: There are definitely aspects of artistic expression that, as in many cases, transcend the boundaries and possibilities of spoken language; this is one of the main reasons why I’m deeply engaged in film and video work as a part of my research; for me, it’s become clear that discursive expression can often fail to grasp the complexities of images, sounds, and other sensory experiences that can be shared between people.

SM: Raphael, your doctoral dissertation explored the European history of what you call the “so-called ‘art of the insane’” in Europe. I share your emphasis on the questionable attributions of insanity and madness to the artistic genius often expressed in the art you studied and this of course relates to the art in your exhibit. To the extent that there is “madness,” perhaps this applies in a positive way to all great works of imagination rather than as psychopathological label attributed to artists dealing with health and well-being challenges, conditions that often require additional strength of character. How does this exhibit relate to your dissertation? Is there an expansion? Does it present new questions? Are there commonalities? Do you also feel connections to the comments of Daniel Wojcik in issue 4:1 of this journal?

Raphael Koenig: I was delighted to discover the work of Daniel Wojcik in CAET, and read his book with great interest: I think that, while we were looking at slightly different contexts and geographic areas (mostly American self-taught art for Daniel, and the history of the reception of self-taught artists in France and Germany for my dissertation), we reached similar conclusions: labels such as “outsider art” or “art brut” have to be historicized and critically questioned, as more often than not they constitute a distorting layer that hinders our reception of artworks that should be taken much more seriously: the focus on the internal logic of the works, the context of their creation, etc., should be central. That’s what we tried to do in our exhibition catalogue, by combining a thorough socio-historical introduction offering insights into the respective contexts of Atelier Yamanami and Nanjing Outsider Art Studio with a detailed formal analysis of each work we presented in the show, trying to understand how they function visually as artworks rather than dwelling on anecdotal biographical elements for each artist, which is too often the case in texts dealing with self-taught art. We tried to comment on artworks produced at Atelier Yamanami and Nanjing Outsider Art Studio with the same degree of precision and rigor that is commonly used to understand the visual vocabulary of major modernist artists.

More generally, I think that there are two main aspects of the historical reception of self-taught art: on the one hand, a fascination for a supposedly “primeval” mode of expression that is part and parcel of the history of primitivism (with the “art of the insane” being part of a highly problematic cluster that also included children’s drawings and traditional forms of non-Western art); we need to engage critically with this legacy.

On the other hand, a much more compelling line of inquiry, which was already clearly expressed by psychiatrists like Hans Prinzhorn or François Tosquelles (who was encouraging patients such as Auguste Forestier to create artworks from the mid-1940s onwards), has to do with questions of norms and normativity: looking at artistic creations produced in exceptional circumstances by people who were often socially marginalized and considered “abnormal” or mentally ill, as a meaningful detour that would force us to rethink and expand the notion of normativity itself, promote a more inclusive definition of mental health, combat discrimination and stigmatization, and allow for a much broader range of artistic creations to be taken seriously as artworks.

Lately, with important exhibitions of self-taught art at major art institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum, the Guggenheim, or the Venice Biennale, the art world seems to have been very receptive to this idea. I truly hope that academia will follow suit, and that there will be more widespread scholarly engagement with these issues: this is why I am particularly grateful for Daniel Wojcik’s book, and indeed for the issues of CAET that deal with this topic, including this one.

SM: Benny, can you tell us more about your work with Media Anthropology and your dissertation project, “Videoworlds: Media Ecologies of the Moving Image in Contemporary China”? Your work with independent cinema, contemporary art, and popular performance in China is of great interest to our readers?

Benny Shaffer: In my dissertation research, I explore how distinct social worlds emerge through video as a medium in contemporary China, ranging from how performers use video for self-promotion in the entertainment industry in southwest China’s Yunnan Province, how independent filmmakers produce, circulate, and exhibit their work through underground networks of peers and scholars, as well as how moving image artists navigate barriers of censorship and improvise to exhibit their work within the burgeoning contemporary art world of cities like Beijing and Shanghai. I’ve been interested in video as a medium for many years – its portability, its reproducibility, and its potential for mass circulation – and also how the work of performers, filmmakers, and artists who work on the edges of the entertainment industry and art world can reveal critical perspectives on what is happening at the center or most dominant positions of these fields of cultural production.

SM: In the catalogue you describe how you used video as a research tool when visiting the workshops in China and Japan. In developing art-based research we also use video as a primary mode of documenting empirical features of the work, showing artistic evidence and the process of creation, all of which present a wealth of opportunities for reflecting on actual experience.

Benny Shaffer: My training in media anthropology – both as a methodology for studying media formats like video, as well as using video as a medium for my own research-based artistic practice – always informs the way I engage with new communities of people during the research process; this approach was no exception when Raphael and I came to know and work with the participants in the workshops in both China and Japan through the use of a video camera. It was important for Raphael and I to familiarize ourselves with the staff and participants and be sensitive to the rhythms of their daily lives and artistic practices throughout the process of recording video with them. We were pleased with how comfortable and accommodating they were, and how the footage was able to intimately document the artists’ ways of working without having to defer to descriptive text or explanatory voiceover.

SM: How do you assess the impact of the Harvard exhibition?

Benny Shaffer: We were pleased that the exhibition was installed in a space that receives regular traffic from people of many different backgrounds, fields, and areas of expertise. While not everyone who enters the space on the way to other events would stop and take the time to look closely at the artworks, we found that whenever we were in the space, some people would inevitably stop to view the works, read the descriptions, and discuss their reactions with friends and colleagues. The work of the self-taught artists on display in this exhibition also challenges artistic conventions in ways that many viewers may not have experienced before, yet many people seemed to view the works with open minds and found them impressive and inspiring.

SM: How did Guo Haiping and Masato Yamashita respond to the work in Cambridge?

Raphael Koenig: It was wonderful to be able to bring Guo Haiping and Yamashita Masato together in one room: even though they cannot communicate directly as they do not have a single language in common, I think that both of them were struck by the similarity of their approaches and outlooks, and extremely interested by the artworks produced in each other’s workshops.

Their work is also incredibly rewarding and exciting, but it is by no means an easy line of business and it takes a lot of effort and dedication: I think they were both happy to have an opportunity to share their ideas and be able to engage with a broader community. They are also not used to academic contexts, so I think they were both particularly excited to spend time and engage with scholars, students, and art therapy practitioners at Harvard and at Lesley University.

They were also happy to bring news of the exhibition to their respective communities: for people with mental disabilities or mental illness who are often discriminated against or stigmatized, gaining recognition and seeing that their work is exhibited and appreciated in other cultural and institutional contexts can be hugely important.

More generally, I think it is fair to say that everybody involved felt that a real intercultural dialogue was taking place, and that there was a palpable sense of international momentum: initiatives such as the Nanjing and Yamanami workshops are increasingly attracting mainstream attention, and getting the recognition that they deserve.

About the Interviewer

Shaun McNiff, University Professor, Lesley University, Cambridge, MA, USA. Email: smcniff@lesley.edu

About the Interviewees

Raphael Koenig, Leonard A. Lauder Fellow in Modern Art, Metropolitan Museum, NYC, and Associate Scholar, Department of Comparative Literature, Harvard University. Email: Koenig@fas.harvard.edu

Benny Shaffer, PhD Candidate in Anthropology and Critical Media Practice, Harvard University Email: bennyshaffer@fas.harvard.edu

References

Prinzhorn, H. (1972) The artistry of the mentally ill. New York: Springer-Verlag (Originally published as Bildnerei der geisteskranken in 1922).

Suzuki, A. (2017). Voices of madness in Japan: Narrative devices at the psychiatric bedside and in modern literature. In G. Eghigian (Ed.), Routledge history of madness and mental health (pp. 245–260). London and New York: Routledge.

Wojcik, D. (2016). Outsider art: Visionary worlds and trauma. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.