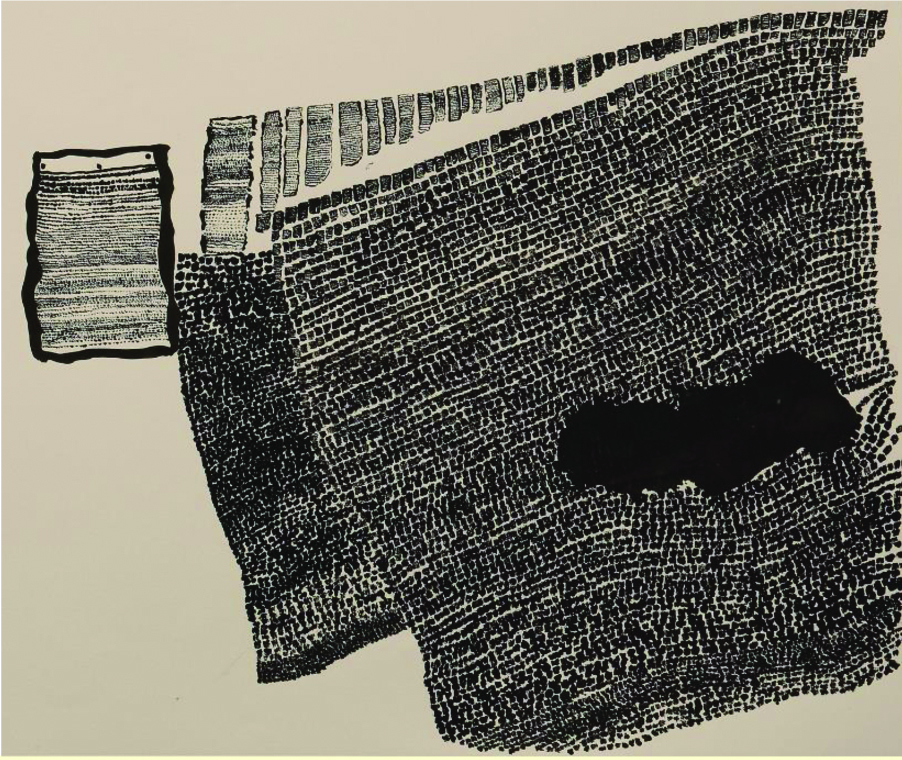

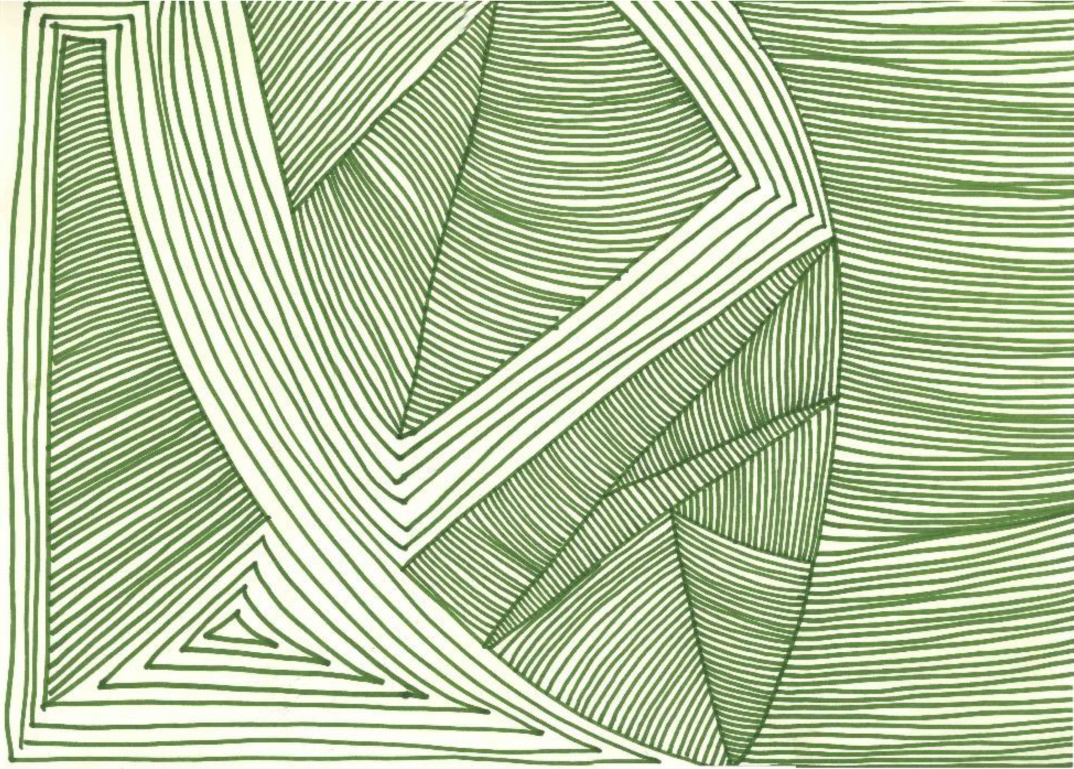

FIGURE 1 | Yoshikawa Hideaki, Eye Eye Nose Mouth, 38.1 × 54 cm, 2013.

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2019) 5(1):3–13 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2019/5/2 |

From Stigma to Affirmation: Advocacy Through Art in China, Japan, and Beyond

A Special Section on Eye Eye Nose Mouth: Art, Disability, and Mental Illness in Nanjing, China and Shiga-Ken, Japan Harvard University Asia Center Exhibition, 2019

在中国和日本艺术世界的边缘扩展正常化

哈佛大学亚洲中心特展(2019)- 眼鼻嘴:中国南京和日本滋贺县的艺术、残疾和精神疾患

Lesley University, Cambridge, MA, USA

Abstract

This is an introduction to the special section dealing with the 2019 Harvard University Asia Center exhibition. The showing of art from Nanjing, China and Shiga-Ken, Japan workshops and the accompanying Harvard symposium feature a unique artistic advocacy seeking to change social attitudes about people living with disability and mental illness. The reflective essay reviews the exhibition and accompanying catalogue and draws parallels between the East Asian workshops and the art therapy studio movement in the West.

Keywords: artistic advocacy, stigma, disability, mental health, self-taught artists, outsider art, art brut, studio-based art therapy, Nanjing Outsider Art Studio, Atelier Yamanami, Guo Haiping, Masato Yamashita

摘要

2019年哈佛大学亚洲中心展览“眼眼鼻嘴:艺术、残疾和精神疾病”专题介绍,日本Shiga-Ken和中国南京。南京艺术展和Shiga-Ken工作坊以及哈佛专场以独特的艺术主张为特色,寻求改变社会对残疾人以及精神疾病的态度。这篇文章回顾了展览与目录,将东亚工作坊和艺术治疗工作室与西方进行相比较。

关键词: 艺术宣传, 污名, 残疾, 心理健康, 自学成才, 外来艺术, 艺术brut, 工作室艺术疗法, 南京外来艺术工作室, Amanlier Yamanami, 郭海平, Masato Yamashita

Introduction to the Interview with Raphael Koenig and Benny Shaffer

While developing the special issue of Creative Arts in Education and Therapy (CAET, 4.1, 2018) focused on Outsider Art in China (featuring the Nanjing workshop led by Guo Haiping and the book on Outsider Art: Visionary Worlds and Trauma by Daniel Wojcik, 2016) I was unaware that a few blocks away in Cambridge, Massachusetts two Harvard University doctoral candidates were at the same time preparing an exhibition at the Harvard Asia Center of art from the Nanjing Outsider Art Studio and the Atelier Yamanami in Shiga-Ken, Japan (Eye Eye Nose Mouth: Art, Disability, and Mental Illness in Nanjing, China and Shiga-Ken, Japan).

Raphael Koenig and Benny Shaffer conceived and organized the exhibit based on their research in China and Japan involving the Nanjing and Shiga-Ken workshops. Koenig defended his dissertation in September, 2018 [Art Beyond the Norms: Art of the Insane, Art Brut, and the Avant-Garde from Prinzhorn to Dubuffet (1922–1949)] and Shaffer is now completing his [Videoworlds: Media Ecologies of the Moving Image in Contemporary China].

In preparing the academic symposium accompanying the exhibition (Art, Disability, and Mental Illness in Nanjing, China and Shiga-Ken, Japan), Koenig and Shaffer hoped to involve the art therapy community via Harvard’s Cambridge neighbor, Lesley University. As described in the interview included in this special issue, they felt it important to make connections amongst various disciplines in order to realize the full social and international significance of the work being done in the China and Japan workshops. In addition to art therapy, these disciplines included anthropology, disability and mental health law, psychiatry, and art.

Guo Haiping brought the CAET special issue to the attention of Koenig and Shaffer who invited me to participate in their symposium session involving Guo and Masato Yamashita, Director of Atelier Yamanami. The workshop directors also wanted to relate to the arts therapy community so with the support of the Institute for the Arts and Health and its director Vivien Marcow Speiser, a companion event was held at Lesley University (Art as Healing in China and Japan: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on New Community Based Applications).

I had hoped to do more with the focus on self-taught artists in China featured in issue 4.1 and wanted to begin a serious CAET engagement with Japan, never imagining that the rich materials presented in the current issue would be accessible in my Cambridge neighborhood. We are also fortunate to engage Akihito Suzuki of Keio University in Tokyo, an authority on psychiatric history in Japan, who in addition to reflecting on the Harvard Asia Center exhibit, introduces our readers to the 20th century history of art made by patients in Japanese psychiatric hospitals and the broader cultural relationship between art and mental illness in Japan.

The interview with Raphael Koenig and Benny Shaffer explores the origins and objectives of their research which aligns closely with CAET’s commitment to cooperation across academic disciplines and cultures. We are delighted to feature their work which significantly advances the journal’s mission.

Reflections on Eye Eye Nose Mouth

The Harvard Asia Center exhibition and the accompanying catalogue, Eye Eye Nose Mouth: Art, Disability, and Mental Illness in Nanjing, China and Shiga-Ken, Japan (Koenig & Shaffer, 2019), integrate a showing of wondrous visual art with social advocacy that addresses not only conditions in China and Japan but the world community. The exhibition “works to combat stigma” and to achieve a “paradigm change” in relation to how people with disabilities are viewed and treated in society. The vehicle of transformation is a presentation of the positive and life-enhancing artistic expressions of people living with these conditions apart from the so-called norm. Koenig and Shaffer hope that viewer engagement with the work of the artists draws attention to the operations of the workshops that support them.

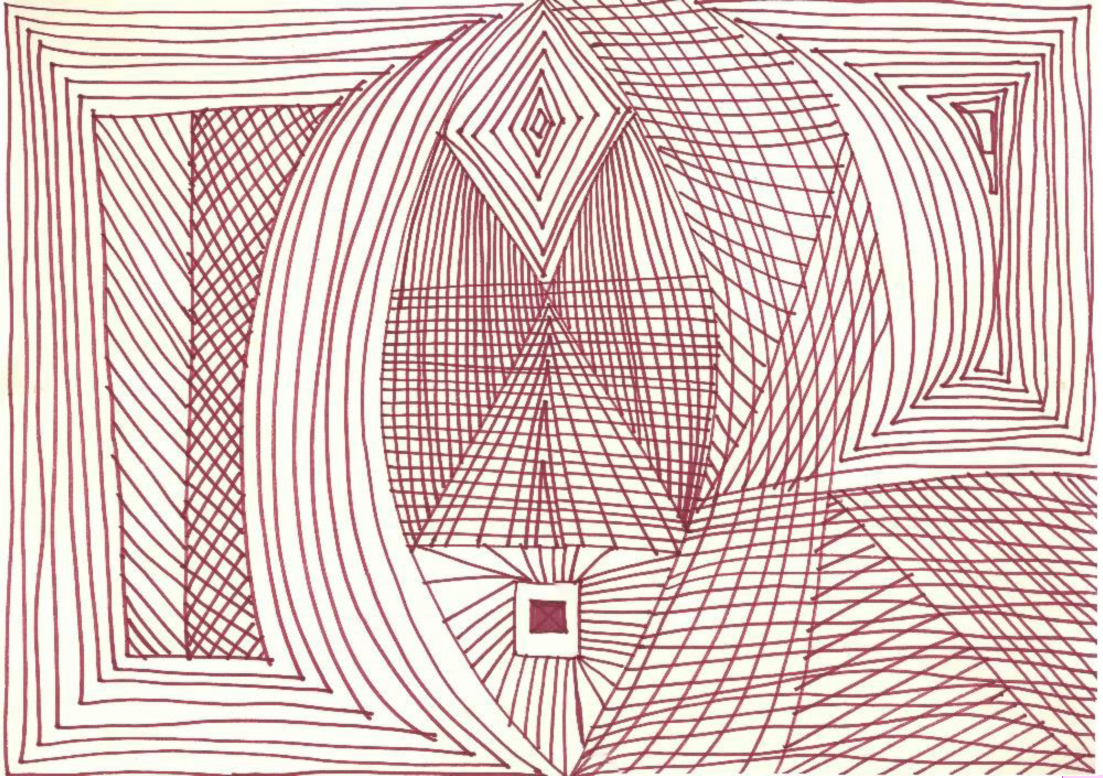

The exhibition and catalogue title is derived from the 2013 Sumi ink on paper drawing by Yoshikawa Hideaki, Eye Eye Nose Mouth (Fig. 1), which is also on the cover of the catalogue.

FIGURE 1 | Yoshikawa Hideaki, Eye Eye Nose Mouth, 38.1 × 54 cm, 2013.

The composition is based upon the repetition of “three dots and a short horizontal line” which suggest a person’s face with two eyes, nose, and mouth.

The catalogue includes introductory and critical essays by Koenig and Shaffer which are followed by presentations of the work from the two workshops, beginning with descriptive essays by the directors, Yamashita Masato and Guo Haiping, and followed by full page color illustrations of the art. The art works are accompanied by terse commentaries on their qualities, approaching the work in a manner that is consistent with the format of an exhibition catalogue reflecting on the significance of the expressions rather than the all-too-common focus on discussing the art as a manifestation of various pathologies.

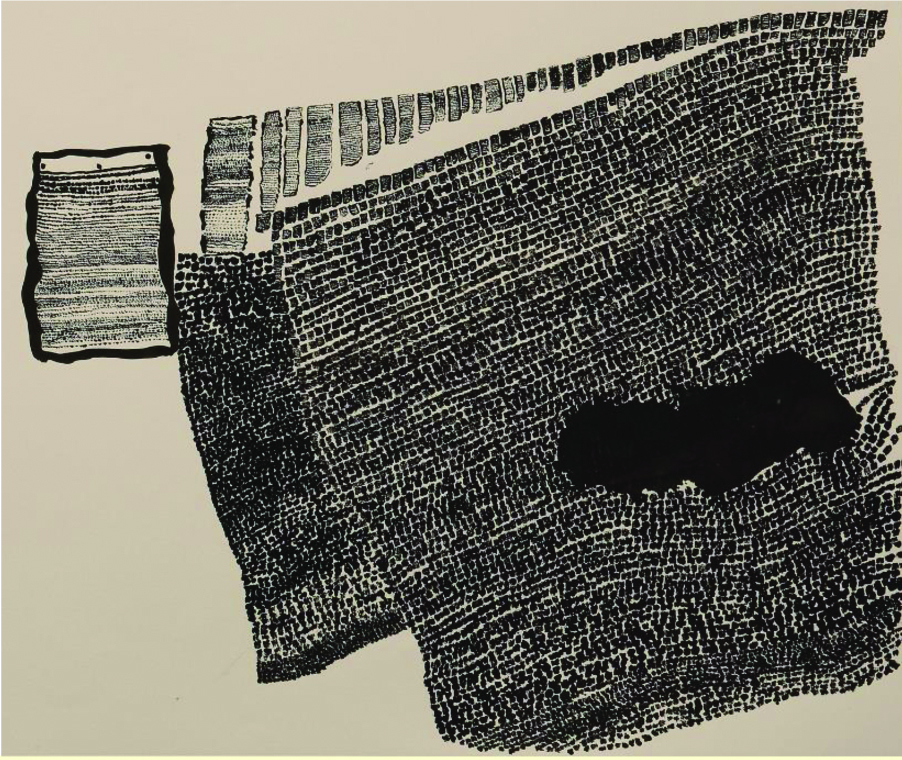

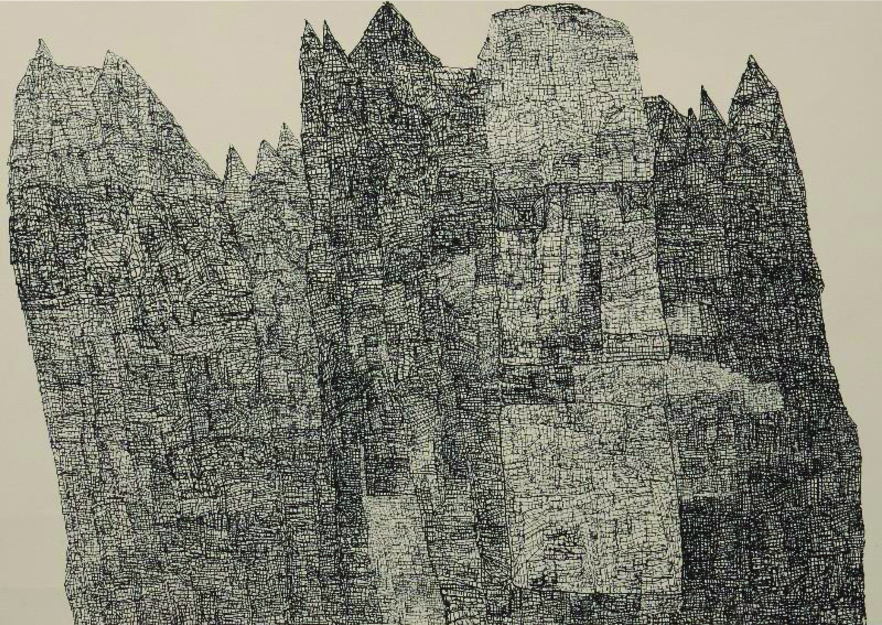

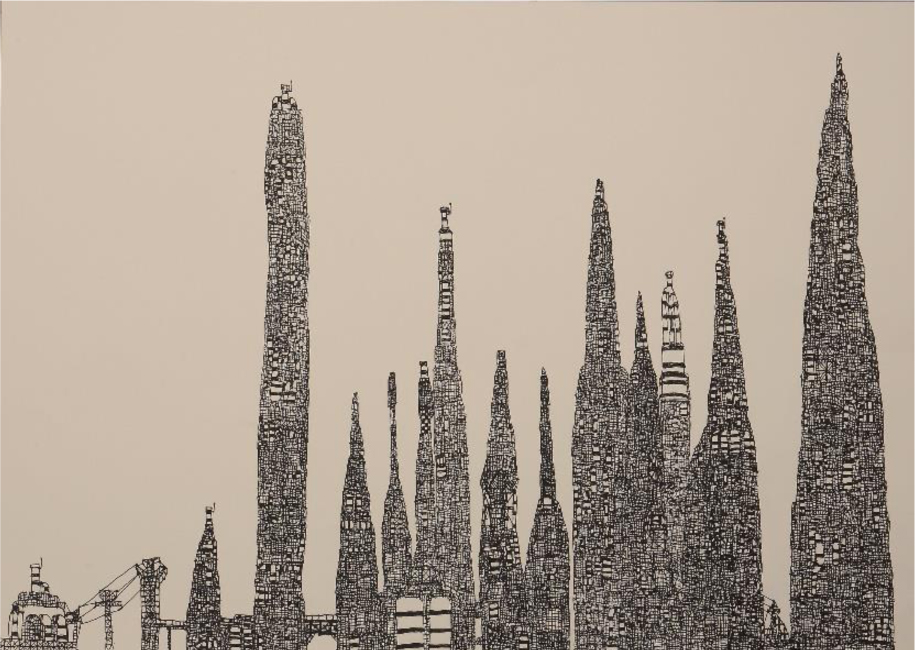

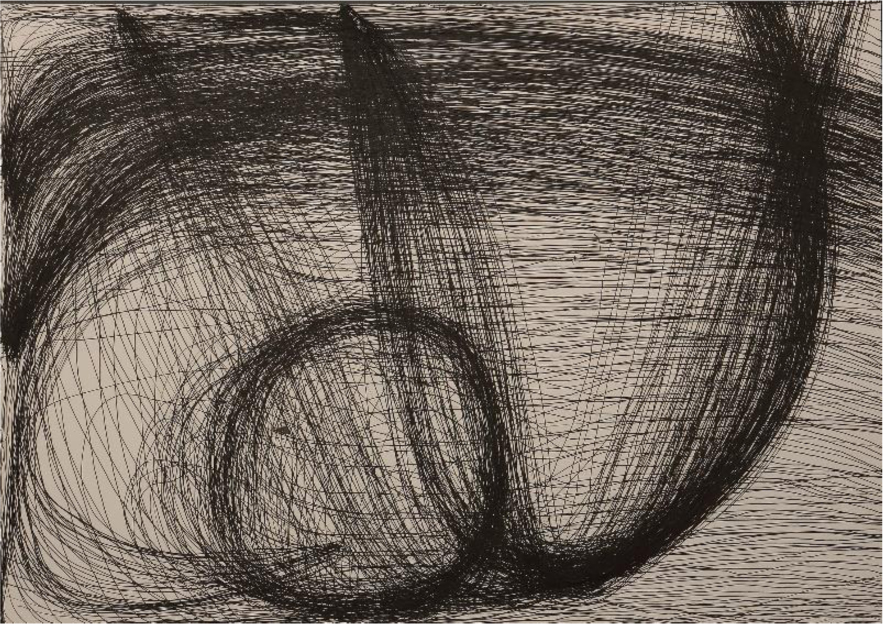

For example, in response to two ink pen on paper drawings that were made in the Yamanami workshop by Takenaka Katsuyoshi, Wall City (Fig. 2) and Industrial Zone (Fig. 3), the catalogue commentary explicates the artist’s graphic method.

FIGURE 2 | Takenaka Katsuyoshi, Wall City, 38.3 × 54.3 cm, 2015.

FIGURE 3 | Takenaka Katsuyoshi, Industrial Zone, 54.3 × 76.6 cm, 2018.

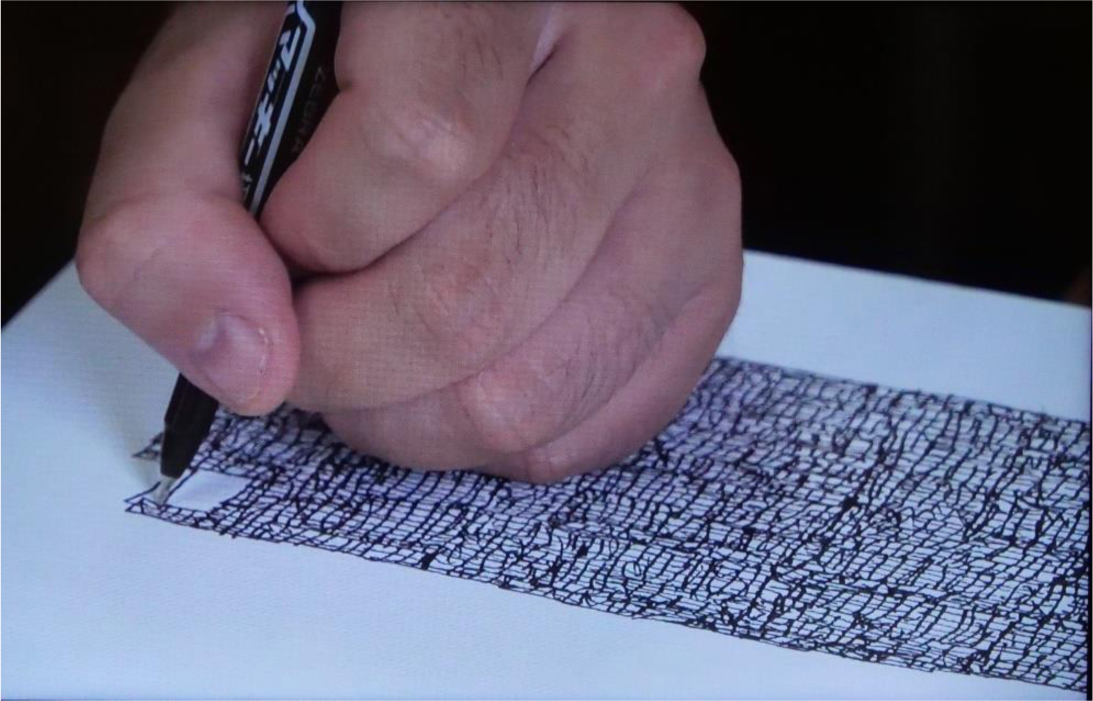

FIGURE 4 | Takenaka Katsuyoshi at work.

...drawings grow from a single, pixel-like square, replicated with variations to become complex monumental structures, linking up with other clusters, and eventually filling the page. The resulting uncanny qualities of these architectonic drawings derive as much from this unconventional process of connective accumulation as from the ambiguous nature of the representation itself…

I am inspired by these three drawings. They reinforce what happens in my worldwide studio work with others where the repetition of the most elemental gestures and forms can be a universally accessible way of helping every person make significant art. Hideaki and Katsuyoshi take the repetition to new levels of discipline, minute precision, persistence, and artistry.

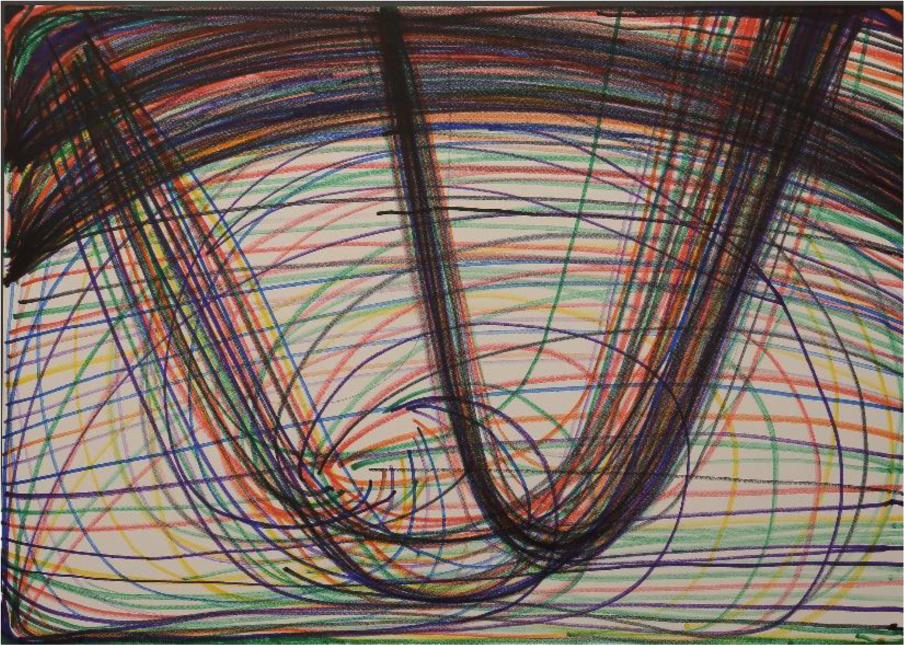

My own experience with the movement basis of expression and viewing artistic expression as a “force of nature” corresponds closely to the Nakagawa Momoko drawings with pens on paper (Fig’s. 5 & 6). Momoko’s art illustrates how sustained, vital, and repeated movement will reliably generate visually evocative expressions.

FIGURE 5 | Nakagawa Momoko, Ballpoint pen on paper, 54.4 × 76.9 cm, 2017

FIGURE 6 | Nakagawa Momoko, Felt tip pen on paper, 54.4 × 76.9 cm, 2017.

The authors’ commentary notes how the artist works spontaneously with “stylized repetition” of the letters of her name and transforms them through “ritualized gestures.” These artistic processes manifest elemental foundations of expression that permeate all forms of art-making. They are to human experience like breath, and in my work we strive to help people everywhere access them.

CAET issue 4.1 presents many paintings from the Nanjing studio and the Harvard Asia Center exhibition includes more. Works by Niu Niu also build compositions through the repetition of line patterns. The Oolong Tea series from 2018 (Fig’s. 7 & 8) generates intricate abstract compositions originating from “the beverage that sits atop her studio desk.”

FIGURE 7 | Niu Niu, Oolong Tea [0606], Felt tip pen on paper, 38 × 53 cm, 2018.

FIGURE 8 | Niu Niu, Oolong Tea [0613], Felt tip pen on paper, 38 × 53 cm, 2018.

This building process through repeated line patterns permeates art in all regions of the world, from Sol LeWitt and Agnes Martin to aboriginal Australia, and is comparable to core processes of nature. In relation to transcendent artistic forms and gestures, Sun Yeu’s gouache paintings on paper (Fig’s. 9 & 10) evoke comparisons to minimalist stained canvases from the New York abstract expressionist era.

FIGURE 9 | Sun Yeu, Untitled [DC031], 38×53 cm, 2017.

FIGURE 10 | Sun Yeu, Untitled [DC071], 38 × 53 cm, 2017.

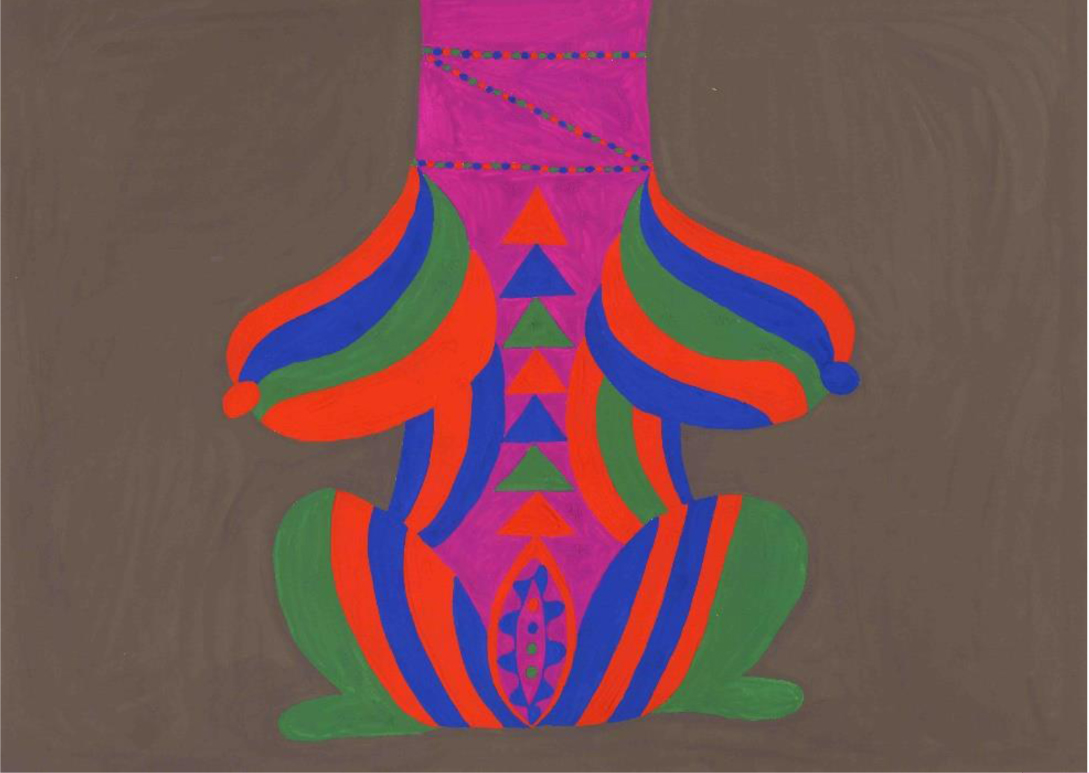

Gouache paintings by Li Jie (Fig’s. 11 & 12), who trained in graphic design as contrasted to the self-taught artists in the Nanjing studio, infuse the catalogue with the energy of “vibrant colors,” imagination, and connections to personal “reproductive and parental” processes.

FIGURE 11 | Li Jie, Cracked Egg No. 3, Gouache on paper, 38 × 53 cm, 2016.

FIGURE 12 | Li Jie, Tree Frog, Gouache on paper, 38 × 53 cm, 2016.

The way in which the art and artists are presented, in keeping with the conventions of a quality gallery showing, is a primary stratagem for realizing the exhibition’s advocacy objectives. This departs from approaching the artists as representatives of a particular ‘population’ of people and presenting the usual case history information dealing with their particular health and life challenges. Even in the most well-intended situations, this more clinical and typological perspective on the art and artist, results in viewers perceiving the expressions within the context of disability and illness. In the mental health field there is a worldwide and longstanding pathology paradigm that consistently and exclusively reduces the life-affirming expressions of a person’s art to negative conditions, all of which reinforce the stigma from which the exhibition and the Nanjing and Shiga-Ken workshops strive to “unambiguously distance” themselves.

In their Curatorial Decisions essay Koenig and Shaffer describe how they endeavor to reframe how the art created by people with disabilities is viewed and classified and this goal has been accomplished with excellence. There are many of us in art therapy who share these values and approaches to art. The practice of what is called studio art therapy is particularly in sync with the approaches of the Nanjing and Shiga-Ken workshops.

A 1995 special section on Studio Approaches to Art Therapy edited by Cathy Malchiodi in Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association focused attention on this important thread of art therapy practice which is progressively taking a prominent place in the profession. In her introduction Malchiodi emphasizes the need to understand, as do Koenig and Shaffer, what these environments do. Many publically oriented programs are being developed such as the Art Hives (Timm-Bottos, 2017) and Open Studio movements which offer a service in neighborhood studios. The creation of these offerings were buoyed by Pat Allen’s critical positions about overly “clinified” art therapy practice (1992, 1995). And then there is the “portable studio” of our editorial board member Debra Kalmanowitz who together with Bobby Lloyd set up temporary studios in war torn regions (1997).

In 1946 Edward Adamson one of the founders of art therapy in the UK, established an art studio in a large mental hospital with objectives very similar to the Chinese and Japanese workshops. He was influenced by C. G. Jung’s belief in the “art of letting things happen.” The studio was described as an “oasis” that encouraged an “atmosphere of quiet concentration.” It supported the unique creative expression of each person and this early program model has persisted in art-based approaches to art therapy. The classic 1984 publication documenting the work of Adamson, Art as Healing, strikes me as a companion volume to the Harvard show catalogue. It too is a terse and visually appealing art book accompanied by reflective text, with both demonstrating how to present the work we do and the evidence of art in ways that appeal to public audiences.

My own 1970 start in art therapy began in a hospital studio where we innately encouraged the life-enhancing medicines of art and to this day everything I do in training, practice, and research is studio-based. We worked in close cooperation with an art museum, the Addison Gallery of American Art and its visionary director Christopher Cook, to further goals similar to the Harvard Asia Center exhibit. Interestingly enough, our 1972 exhibition calling for a more humane relationship between art and mental health and making art museums more inclusive of art of whole communities, visited Harvard’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts in 1973 and the exhibition catalogue (McNiff, 1974) shares many qualities within this one. The things that we did then have been sustained over the past five decades and there is a close kinship to the Nanjing and Shiga-Ken workshops, especially our common commitment to “what art does” to enhance human well-being within a supportive studio environment (McNiff, 2019).

As someone who works to bring the benefits of artistic expression to all people and who believes that with the right support, every person can make significant art (McNiff, 2018), experience indicates that the impacts on well-being are proportionate to the commitment made by the individual artists. This principle is reinforced by the Nanjing and Shiga-Ken workshops and the Harvard Asia Center exhibition. Koenig and Shaffer confirm how the workshop operations play a crucial role in reinforcing participants and helping them to maintain their levels of involvement. In my practice I have repeatedly seen how positive group environments further individual participation and the generation of creative energy which motivates expression and the transformation of tension and afflictions into affirmations of life; and the reverse happens in repressive group settings.

The supportive communities of creation act like the slipstreams of nature, helping us do things together that might not be possible when creating alone. And as this exhibition illustrates, it is essential to study and communicate the processes that generate these constructive outcomes, and then show and celebrate the work to inform and inspire others. The supportive studio environments described here and emerging worldwide are micro cultures displaying what is possible on a larger social scale when a common purpose is paired with respect and attentiveness to the infinite uniqueness of an individual’s expression and life conditions.

About the Author

Shaun McNiff, University Professor, Lesley University, Cambridge, MA, USA. Email: smcniff@lesley.edu

References

Adamson, E. (1984). Art as healing. London: Coventure (1990, London and Boston).

Allen, P. (1992). Artist-in-residence: An alternative to “clinification” for art therapists. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 9(1), 161–166.

Allen, P. (1995). Coyote comes in from the cold: The evolution of the open studio concept. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 12(3), 22–29.

Kalmanowitz, D. & Lloyd, B. (1997). The portable studio: Art therapy and political conflict: Initiatives in the former Yugoslavia and KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. London: Health Education Authority.

Koenig, R. & Shaffer, B. (Ed’s.). (2019). Eye eye nose mouth: Art, disability, and mental illness in Nanjing, China and Shiga-Ken, Japan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center & Blurb Publishing [79 pages].

Malchiodi, C. (1995). Studio approaches to art therapy. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 12(3), 154–156.

McNiff, S. (1974). Art therapy at Danvers. Andover, MA: Addison Gallery of American Art.

——— (2018). All inclusive art making. NiTRO--Non Traditional Research Outcomes, A Publication of The Australian Council of Deans and Directors of Creative Arts, June 1, 2018. https://nitro.edu.au/articles/2018/5/30/all-inclusive-art-making

McNiff, S. (2019) Reflections on what ‘art’ does in art therapy practice and research. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 36(3), 162–165.

Timm-Bottos, J. (2017). Public practice art therapy: Enabling spaces across North America (La pratique publique de l’art-thérapie: des espaces habilitants partout en Amérique du Nord). Canadian Art Therapy Association Journal, 30(2), 94–99.

Wojcik, D. (2016). Outsider art: Visionary worlds and trauma. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.