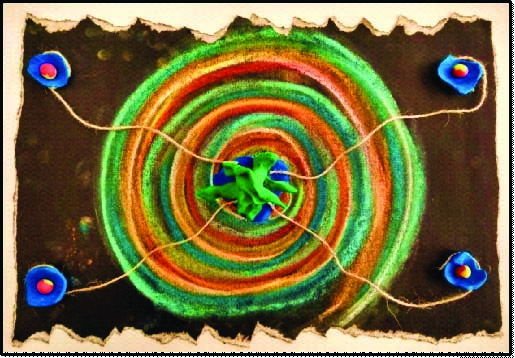

FIGURE 1 | Holding the maelstrom

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2018) 4(2):153–157 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2018/4/24 |

Embracing the Maelstrom: Arts Therapy Training from the Edges of the Whirlpool

Whitecliffe College, Aotearoa New Zealand

Abstract

This piece of arts-based writing explores my personal transition from Arts Therapy student to Arts Therapy lecturer. Further, the roles and relationships between student and lecturer are explored and related to the Māori concept of ako, the idea of reciprocal learning and teaching. This exploration is held by the tenet that the arts process is integral to the teaching environment at Whitecliffe College, with the argument being that trusting in the poietic process supports and facilitates embodied knowledge. The piece further provides a contemplation of students’ experiences of their individual maelstrom (their deep journeys into themselves), the roles of the lecturers as those who help hold those journeys, and the learning gems that can be found along the way.

Keywords: Transitions, arts therapy training, lecturer-student-relationship, roles, trust, arts-based research

I find myself sitting in this space at Whitecliffe once again,

transitioning from student to educator, from the one who learns to the one who teaches.

It was just last year that I went across that stage to get capped as an arts therapist

and now I am here, with the intention to train the next generation.

I am a bundle of feelings – excitement, fear, trepidation.

The unknown, waiting for me.

I watch myself as I watch the students as I watch my colleagues as they watch me.

Intertwined in this mutual-reciprocal-watching-watched-ness,

we are finding ourselves in the midst of a daunting-inspiring maelstrom (McNiff, 1998).

Eager first year PGDip students

alongside an eager first year educator

alongside my (still eager) seasoned colleagues.

I wonder who will be guiding, holding, educating who.

Question arise from deep within my soul.

“What does it mean to be a ‘lecturer’?”

“What does it mean to hold students’ journeys

into the magical wondrous realm of Arts Therapy?”

“And what’s my role in it, as the one who is transitioning the worlds?”

“How does one ‘do’ this, how do I do this?”

FIGURE 1 | Holding the maelstrom

I sit with these questions, cross-legged, trying to relax. The questions gather around me like strange-curious little creatures, each competing for attention, kicking each other out of the way, to be there first, to matter more than all the others. Whenever I try to focus my gaze on them, they disappear. I find myself making gentle yet fierce wider movements, alternating between embracing and pushing out, a balancing act of giving and giving and taking, sharing, a being-togetherness.

Feeling into my embodied alongside my academic knowings (Kapitan, 2018, I find myself reminded of the role of the expert, this much discussed – and at times contested – subject in the field of therapy (Anderson & Goolishian, 1992). But what does it mean to be a ‘not-knowing expert’ when educating others? Is this even a possibility? And what do the arts have to say in all of this? Which is the ‘right’ way for approachingArts Therapy training – from the book into the arts or from the arts into the books? Or both?

As I am sitting here, curiously noticing all these questions,

I will-invite myself to relax into the process once again.

When studying Arts Therapy, I learned to trust the arts,

to trust myself through the arts, to hold (myself in) the maelstrom.

I marvelled at the magical quality of the arts to tell me stories I was unaware of,

to safely lead me into both dark and light spaces,

providing me with a safety net when the pull of the maelstrom was at its strongest.

Now I am finding myself confronted with the task

to trust the arts once more in teaching students.

In teaching them how to hold their own maelstrom.

And that of their future clients.

Maybe ‘trust the process’ (McNiff, 1998) doesn’t suddenly just ‘stop’

when one becomes an educator.

Trusting the arts, the poietic process (Levine & Levine, 2011), is indeed a core component of our training at Whitecliffe College. Continuously, we invite students to embrace the arts and the process, stepping into themaelstrom, holding the space for and with them from the edges and sometimes from within.

I witness their courage and vulnerability as they engage with the arts, therapeutic models, social concepts, daringly bringing who they are and cautiously stepping into who they are becoming. As I admire their bravery, I once again contemplate my role. Searching within, I find myself drawn back to the Māori concept of ako, the reciprocal learning (and teaching) that can occur in the relationship between lecturer and student (Bishop & Berryman, 2009). Within ako, the boundaries in the teaching relationship are both upheld and blurred as teaching-learning becomes a together-with-endeavour rather than something that is done ‘to’ someone. Reflecting on this, I sense that I need to both know and not know, that I can be a ‘not-knowing expert’. Gentle calm fills my body. My soul breathes more freely. Further stepping into my role as an educator, I notice my dislike of the term lecturer, much preferring to view myself as a learning facilitator (Dix, 2018).Holding on to the ‘not-knowing expert’, I am deeply aware of the status and power differential embedded in being an educator:

It is crucial that teachers understand the factors that trigger the status effect, the role of tasks and evaluation that encourage positive interdependence and interaction, and the importance of creating a classroom climate that discourages the development of status hierarchies. (Baker & Clark, 2017, p. 333)

The students are in the centre of their maelstrom.

Some of them are gently moving with the music.

Others are (c)overtly crying.

Others yet again are sitting with their creation as they evolve.

I sit, around the edges of their combined maelstrom, holding the space for and with them.

Holding the space with the other learning facilitators.

Practising ako.

Trusting the process.

Slowly, one by one, the students emerge.

Their hands, open.

Their souls, open.

Filled with gems.

Contemplating these glorious gems, I go back to Dix (2018).He argues how “tertiary learning facilitators should strive to embed ‘learning gems’ into the classroom culture … and [how] we need to embed these gems into a safe place, in the student’s long term memory” (p. 2).Gems. I marvel how those gems can be found through experiential work with students rather than within the more traditional lectures. I wonder whether experiencing Arts Therapy within an educational setting could support the embedding process of the gems, whether they could become ‘long-term embodied knowledge’ (Kapitan, 2018).

I am finding myself sitting at home, contemplating the maelstrom once more.

Contemplating the gems once more.

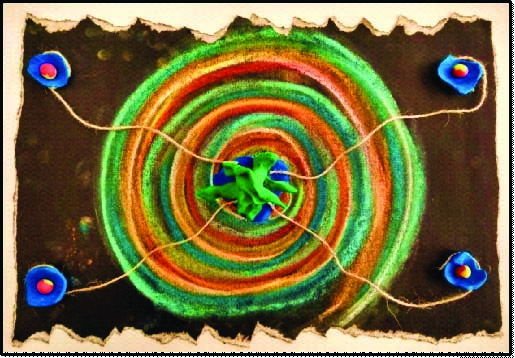

And I find myself drawn to a dream catcher.

It has just come into being.

It has just found its way into this world.

Creating a sense of home.

I wonder about the role of dream catchers.

Whether both learning facilitator and student can embellish them.

Decorate them with the gems they find when they trust the process.

Whether they can help hold the maelstrom.

I wonder…

But for now, I trust.

I trust the arts process.

I trust the students.

I trust my colleagues.

And I am starting to trust myself.

FIGURE 2 | Holding the gems

About the Author

Kathrin Marks is a lecturer in Arts Therapy at Whitecliffe College. Alongside her work as a lecturer, she has a small private practice, facilitates continuing education classes around creativity and wellbeing, and supervises Master of Arts Therapy students for their dissertations. She is curious about the playful and deeply layered aspects Arts Therapy brings both to the work with clients as well as to Arts Therapy training. She loves nature, embraces life, and follows her soul wherever it leads her.

References

Anderson, H & Goolishian, H. (1992). The client is the expert: a not-knowing approach to therapy. In S. McNamee & K. J. Gergen (Eds.), Therapy as Social Construction (pp. 25–39). London, UK: SAGE.

Baker, T & Clark, J. (2017). Modifying status effects in diverse student groups in New Zealand tertiary institutions: Elizabeth Cohen’s legacy for teacher education. Journal of Education for Teaching 43(3): 338–348.

Bishop, R & Berryman, M. (2009). The Te Kotahitanga effective teaching profile. Set: Research Information for Teachers (Wellington) , (2), 27-34.

Dix, S. (2018). Student advancement in tertiary learning environments: Shift from the obstacle course to the dancefloor. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ) , 26(3), 289-291.

Kapitan, L. (2018). Introduction to Art Therapy Research . 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge.

E. G. Levine & S. K. Levine (eds) (2011). Art in Action: Expressive Arts Therapy and Social Change . London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

McNiff, S. (1998). Trust the Process: An Artist’s Guide to Letting Go . Boston, MAShambhala Publications.