FIGURE 1 | ‘Murmuration’ (Green, July 2018)

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2018) 4(2):139–148 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2018/4/21 |

Making-sense of Poietic Presense in Arts Therapy and Education

Whitecliffe College of Arts and Design, New Zealand

Abstract

In this arts-based living inquiry, I attempt to make-sense of my orientation towards poiesis and presense as an a/r/t/s-based practitioner – where I disrupt the word ‘a/r/t/s’ to illuminate my roles as artist / researcher / therapist and teacher / and supervisor. I indwell with several personal hauntings that feel relevant and use story-telling, arts-making, poetic writing and conversations with relevant authors to read the bones that scaffold my practice of poietic presense.

Keywords: Poiesis, Presense, Hauntings, Arts-Based Practice, Therapy, Teaching, Research

In a dimly lit lecture-hall, we stand in a circle. I’m experimenting with a freshly dreamt-up ritual to close five enervating but exhausting days of teaching and learning. I invite the group – comprised of forty arts therapy masters students and educators – to drop-into the sensations evoked by the time we’ve spent deeply immersed in each others’ creative presences. ‘As a parting gift, let’s share what is arising,’ I say and demonstrate a possible beginning. Holding up my index fingers and flowing down my arms and into my fingertips, I imagine the colours and smells, tastes and images, movements and sounds and words and magic workings of our communions. I turn to the student next to me and she responds to my cheeky challenge by raising her own fingers. We share an enchanting moment of hushed anticipation; our gaze is intent upon our effervescent fingertips as we touch them delicately together…as soon as they meet, we instinctively look up into each other’s eyes and dip into a delightful deep and seamless intimacy. With a smile, we break contact – but the connection remains – a golden thread alive between us. ‘Visit with each of your classmates and share…’ I turn up the music and, as I circulate and connect, I’m surrounded by a spontaneous dance – dyads form and dissolve, form and dissolve, exchanging grace and chi. Some are serious – even tearful – others visibly playful, enacting little movement sequences as hands shoulders elbows noses meet and linger. We’re a school of darting fish; a murmuration of starlings swooping and swirling. No further verbal instructions are needed; attunement built through days of arts-based co-creation lets us read and mirror and amplify as we lace between us golden imagical threads to sustain us during the times apart.

FIGURE 1 | ‘Murmuration’ (Green, July 2018)

This arts-based enactment or ‘murmuration’ (Kimberley Walker, personal communication, 20 April, 2018) arose spontaneously from activities that preceded it. Within its supple ebb and flow, I spy the emergent bones that scaffold my poietic presense as a/r/t/s-based practitioner1 ...and I wonder; how do I craft a telling of these bones? The African in me awakens, suggesting my question might better be – how do I read what the bones tell of my arts-based practice? On the breath of this, I embrace arts-based living inquiry (Irwin, Beer, Springgay, Grauer, Xiong, & Bickel, 2008; McNiff, 2013) and indwell with some hauntings that have, of late, niggled, cajoled and yodelled for my attention (Hollis, 2015; Moustakas 1990). They’re a motley crew of moments and memories, writings and arts-pieces that collide and overlap, hinting and hooting at resonances with my core knowing-the-bones intention for this piece. I invite you to join me as I plumb inner liminal spaces to cajole into words and images details of these izipoki2, and then pan out to curate these fragments into the beginnings of an arts-based gestalt-of-self.

Haunting #1: Absent

My mother died 22 years ago today. Today I ride my mountain bike up tight corners, zigzagging over rocks and gravel, climbing beneath a cathedral of blue sky up snow-crested Mount Hutt in New Zealand’s Southern Alps. I’m several oceans away from South Africa and the Hospice bed with crisp white sheets where my mother drew her final breaths. My breaths are rapid, tight and jagged with effort. Hers at the end were slow and raw – falling into vacuums of silence between each laboured breath.

And I was absent when her breath finally failed.

I whisper a poem with space between the words

For the space between our breath

I sigh a poem with space between the words

For the space on your bed-edge that should have held me

I weep a poem with space between the words

For the regret I now feel, to hold the ‘if only…’

I breathe a poem with space between the words

Hoping you may find and fill this space with your presence

I was in my twenties, a privileged white child of Africa who only knew pain vicariously, when my mother told me her cancer – bravely fought and bettered 22 years previously – had returned. Within a month, my father and brother became victims of an armed robbery. Both were shot – my father killed, my bother paralysed – and thus began a tight-cornered, zigzagging journey of chemo for my frail mother and rehabilitation for my brother beneath an overarching cavern of mourning for us all…

…and while I was physically present on this haphazard journey, I absented myself emotionally and spiritually, being ill-equipped to cope with the emotion-saturated soul-malaise into which I was thrust. My British mother had modeled emotional restraint throughout my upbringing. Tears were seen as undoing and shed in private, if at all. I thus contracted against the maelstrom of feelings that churned within and around me. Spiritually and existentially, I was equally maladapted. My lonely teenage years as a spiritually-abristle but judgementally-toxic born-against were trampled underfoot during my activist university period where I tangoed with atheist existential thinkers who made meaninglessness their mantra. These leanings were, in their turn, disrupted by my work within Zulu communities where ancestral spirits roamed freely. Dangling betwixt-and-between ontologies, it felt safest for me to retreat into to the narrative that – as the ‘last man standing’ – I needed to be strong and resolute and not let emotional or existential angst swarm over me. I armoured up with pragmatic tasks – organising and arranging and fussing over the tumbling welter of practical details that arise post-death and during-chemo-and-rehab.

As my brother slowly learned to manage his unresponsive body, his wheelchair and his dashed dreams, my mother grew smaller – her eyes and thoughts beginning to wander elsewhere. Finally, eight months after my father’s death, she was ready to leave. Based on her determination to suffer in private, I convinced myself she didn’t want me to witness the possible indignity of her departure. The evening before her early-morning death, a nurse caught my arm as I was leaving. ‘It will be tonight,’ she told me urgently, trying to walk me back into the slow-breathing room where I’d already said my farewells. I pulled free – sobbing – and fled.

And I was absent when her breath finally failed.

Haunting #2: Absent but coming present

It’s five years since I lost my parents and my brother lost his legs. My first husband and I are also losing each other. I live at the nexus of my tragic tale, demonstrating to all how well I’m coping…but I confuse coping and controlling. I sidestep the larger gestalt-of-self as I absent myself from my emotional and existential throbbings by mercilessly controlling my thoughts and feelings – and my body. My sticky web of control extends beyond me and I attempt to control others…especially my husband. I cast his personal struggles as selfish – surely I have dibs on suffering? Finally, he hangs himself from a small barred window. His bulldog Wallace and I sit on the floor in the miasma of spilt pee with his grey cold body. I hold his chilly hand as people come and go. Here, I have no control. Everything is beyond me. I’m numb, but strangely I’m beginning to come present…

FIGURE 2 | 'Space between' (Green, August 2018)

I retch a poem with space between the lines

To hold my heart and soul, crowbarred open by your wilful death

I vomit a poem with space between the lines

To hold my heart and soul, sitting beside your frigid body

I howl a poem with space between the lines

To hold the regret I now feel, space for the ‘if only…’

I groan a poem with space between the lines

Hoping you may find and fill this space with your presence

Several nights later, my tears finally find me. I sobwrenching guttural sobs. A beautiful steadfast friend stays with me. For what feels like hours she’s simply there – present with me in this appalling, ragged, wounded space. Later, she gently rubs my back to help me sleep.

She offers me my first, and probably most compelling, example of presence…and it takes root in me.

Making-sense #1: What is the essense of presense?

Ideas of ‘absence’ and ‘presence’ flavour these tellings. I roll these words in my mouth like boiled lollies. My tongue teases apart their distinct tastes – chalk and cotton-wool, spring daffodils and salt-sea-spray – but beneath these I’m drawn to the gravelly crunch and fizz of popping candy – a flavour they seem to share. Wonderings arrive about their collaborative use of the word ‘sense’ lurking incognito behind a ‘c’…I muse how when I evict the ‘c’ and add an ‘s’ they explode into life upon my palate. For me, the spectrum of presense is sensual – encompassing varying degrees of abstaining, dieting, sampling, savouring and devouring experiences through my physical senses of sight, sound, taste, touch and smell – as well as through my soul-sense/intuition, my cognitive making-sense and my orientational sense of purpose/direction.

Haunting #3: Teetering, hovering, balancing

As I revisit these personal hauntings with a sense of terror and wonder, several creations call for my attention. Over the past year, I’ve crafted constructions that play with tension, balance and movement. I’m inquisitive about how these metaphors speak to the tangled oscillating journey from my early absenses to my current present awash with presense. Writing my trauma-tales, I mourn for the years I spent cauterising myself...and yet I’m able now to feel into this pain tenderly – with a poise and grace that, frankly, astonishes me – it is so other than my beginnings. And I perceive this compassionate balance of poietic presense within my kinetic creations. While it’s elusive – playing peek-a-boo with me – I also see it arrive at times in my work as arts-based practitioner. I quicken with curiosity at the contrast between how then (as my mother struggled for each breath) I contracted and fled and now (as clients and students move into difficult places where they too struggle for breath) I can often expand and stay present.

Making-sense #2: What is the plural of presense?

This cascade of words dries as I tune into an uncomfortable prickling in my belly. I gently focus into this felt sense (Rappaport, 2008) which reveals itself as a thorny ethical question: In attempting to map my trajectory from absense to presense, do I expose a vampiric tendency to use the hearts and souls of others to heal my own wounds? Some of the barbs soften when I loosen my grip on the Western cultural construct of individualism and reach into my past to the rhizomatic-fronds of African Ubuntu. Ubuntu is a spiritually unifying vision derived from the Zulu maxim umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu which literally translated means ‘a person is a person through other persons’ (Nepo, 2012). This echoes the golden threads laced between us during the murmuration which, in turn, draw my mind towards the mythic Vedic god Indra’s Net hanging over his palace on Mount Meru. This infinite Net has a multifaceted jewel at each vertex and each jewel is reflected in all the other jewels (China Buddhism Encyclopedia, 2016) mirroring how, in Ubuntu, we find our humanity in each other; this leads me to ponder resonances with attachment theories and with intersubjective and transpersonal forms of psychotherapy… I tweak my kaleidoscopically wandering and wondering mind back to the felt sense of interconnection and add this into my emergent assemblage of poietic presense.

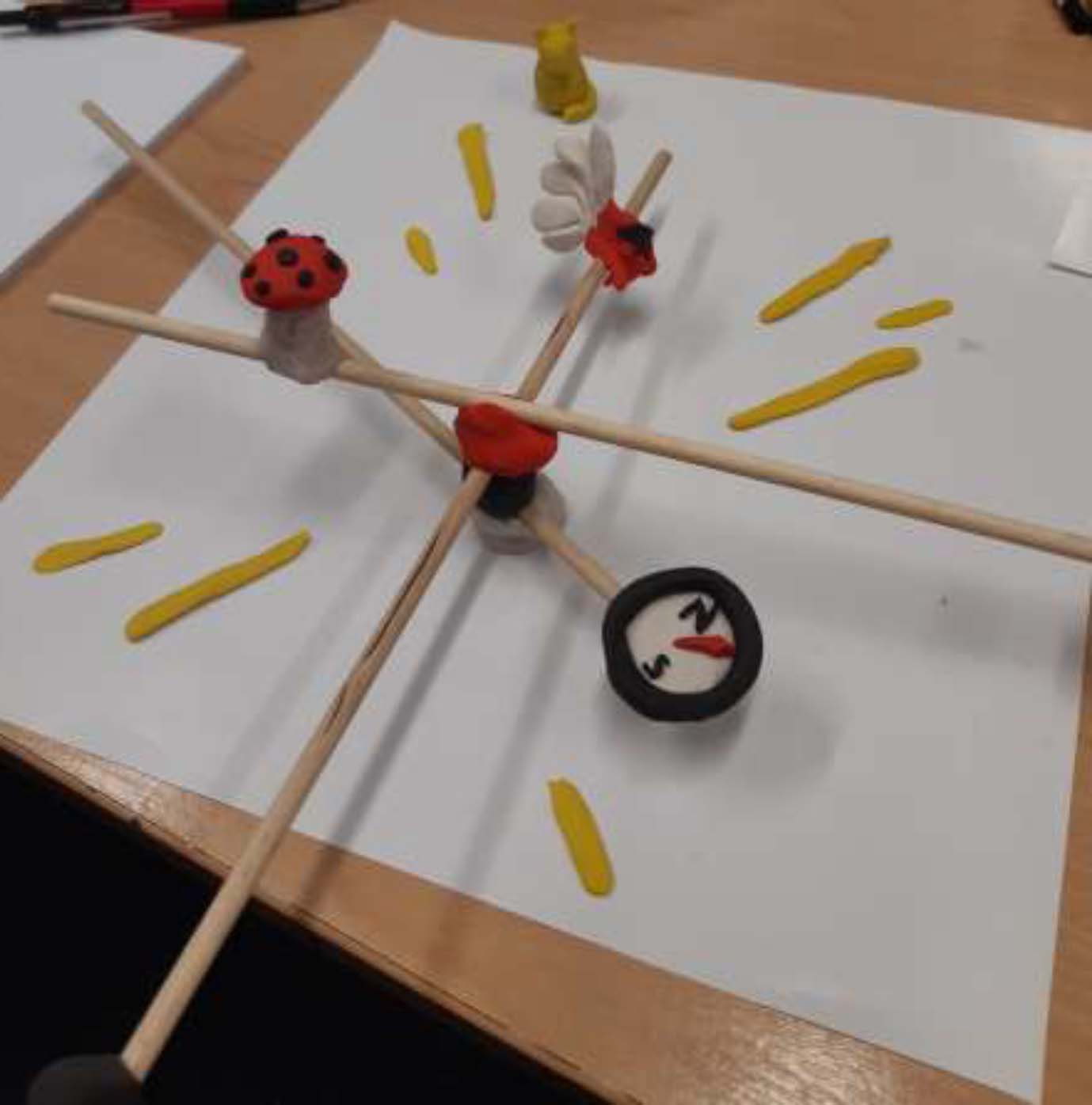

FIGURE 4 | ‘Limbering’ (Green, September 2018)

And so…

I construct a poem poised within the space between me and you

To hold my heart and soul, opened by your presence

I assemble a poem balanced within the space between you and me

To hold your heart and soul, invited in my mine

I compose a poem tip-toeing within the space between me and you

To hold the warmth I now feel, space for the ‘what if…’

You craft a poem dancing within the space between you and me

As you find and fill this space with your presence

Making-sense #3: What do the bones say?

On these pages, I’ve cast the bones of creative conversations with some ghostly-presenses that have niggled, cajoled and yodelled for my attention. Now I collaborate with the words and thoughts of others to flesh-out my tentative interpretations of the bones of poiesis and presense that scaffold me as a/r/t/s-based practitioner.

I begin with poiesis – “the act of shaping what is given to us” (Levine, 2009, p. 25) – as it resonates with my jaggedy personal journey from reactive absense to an increasing ability to practice presense within disruptive and uncertain spaces. When I contemplate my shaping-of-self and of my arts-based practice through the lens of poiesis, I quicken to the relationship between chaos and order – alive in my grapples to cope by controlling or avoiding tumult. Poiesis, for the Greeks, referred to the emergence of intelligible form from chaotic matter; a coming-into-form of the chaos of meaning (Levine, 2009). The creator doesn’t impose a pre-existing plan – instead they invite the material to find its own unique order. Heidegger (1935/1975) expands upon this, viewing poiesis as a way of manifesting or bringing-forth. He offers an alternative to traditional Western philosophy’s emphasis on trying to control life by thought – a will-to-power dominating my initial responses to distress. In Heidegger’s (1935/1975) phenomenology, poiesis is a letting-be (surrendering to a process rather than a wilful intellectual act) for something to come; the creator must relinquish control and critical intention and rather be fully present to the vagaries of life and the creative process. This paradoxical will-to-not-will invites possibilities for ecstatic threshold-moments if the liminality it evokes can be endured and even played with (Heidegger, 1935/1975; Levine, 2009; Turner, 2004). Certain core features infuse this poietic liminality: familiar structures are void; death strikes – whether metaphorical or literal (or both, as in my case); confusion and powerlessness ensue. If these can be endured and opened for what-may-come, chaos may manifest its form in art, re-organising what preceded it.

Embracing these transitional liminal spaces requires presense. In ponderingpresence, I borrow from the mindfulness and focusing-orientated schools of therapy (Rappaport, 2014). Presence here is holistic and considers the whole of the arts-based being;the Western emphasis on cognition becomes simply another strand braided into the physical, emotional, soulful and social. All are wooed and welcomed with compassionate non-judgement and this engenders the Ubuntu of intra- and inter-subjectivity – we embrace our interactive roles as beings both created by and co-creating our experiences of living, grieving, learning, celebrating and arts-making. Burrowing my African roots into the soil of Aotearoa3 where I now live, I nudge out the boundaries of presense to include hauntings – the presense of wairua4 and ghosts. Poietic processes that engage with transitional liminal spaces welcome with curiosity and wonder the presense of the invisible and unseen in our living, therapeutic and teaching spaces and processes. This includes our intuition and felt-sense (Rappaport, 2008), the presense of those not materially here such as ancestors and those we carry within our bones and those – such as yourself – who engage with and respond to our words and art…

FIGURE 5 | ‘Balancing’ (Green, September 2018)

I’ve created a poem with space between the bones

For your breath, your muscles and sinews

I’ve danced a poem with space between the bones

For your thoughts and hopes and responses

I’ve sculpted a poem with space between the bones

For the ‘what if...’ that my words may have awoken in you

We sing a poem with space between the bones

For the ways that you and I fill this space with our presense

1Here I borrow from the a/r/tographers to disrupt and particularise ‘a/r/t/s’ to speak from my artist/researcher/therapist&teacher/supervisor selves (Irwin, Beer, Springgay, Grauer, Xiong, & Bickel, 2008).

2The Zulu word for ghosts.

3New Zealand

4Māori for the spirit of persons that exist beyond death (“wairua”, 2018).

About the Author

Deborah is senior lecturer at Whitecliffe College of Arts & Design, New Zealand. Following a career within the South African University and Health sectors, she moved to New Zealand, gained her Master of Arts in Arts Therapy (Whitecliffe) and spent several years working with those affected by the Canterbury earthquakes (2010/11). She received her PhD (University of Auckland) for an autoethnographic arts-based thesis exploring this experience. She has published in books and journals and has presented at conferences in Australia, Singapore, New Zealand and Canada.

References

China Buddhist Encyclopedia (2016). Indra’s Net. Retrieved from http://www.chinabuddhismencyclopedia.com/en/index.php/Indra%27s_net

Hollis, J. (2015). Hauntings – dispelling the ghosts who run our lives. NC: Chiron Publications

Heidegger, M. (1935/1975). Poetry, language, thought. (A. Hofstadter , Trans.). London & Toronto: Harper & Row, Perennial Library.

Irwin, R. L., Beer, B., Springgay, S., Grauer, K., Xiong, G., & Bickel, B. (2008). The rhizomatic relations of a/r/tography. In S. Springgay , R. L. Irwin , C. Leggo , & P. Gouzouasis (Eds.), Being with a/r/tography (pp. 205-220). Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Levine, S. K. (2009). Trauma, tragedy, therapy: the arts and human suffering. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Maori Dictionary. (2018). Wairua. Retrieved from http://maoridictionary.co.nz/search?&keywords=wairua

McNiff, S. (Ed.). (2013). Art as research: opportunities and challenges. Chicago, IL: Intellect Publishers.

Moustakas, C. E. (1990). Heuristic research: design, methodology, and applications. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Nepo, M. (2012). Finding inner courage. London: Heron Books.

Rappaport, L. (2008). Focusing-oriented art therapy: accessing the body’s wisdom and creative intelligence. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley.

Rappaport, L. (Ed.). (2014). Mindfulness and the arts therapies: theory and practice. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Turner, E. (2004). Communitas, rites of. In F. A. Salamone (Ed.), Encyclopedia of religious rites, rituals, and festivals (pp. 97-101). New York, NY: Routledge. Retrieved from http://cw.routledge.com/ref/religionandsociety/rites/communitas..pdf

Ubuntu (2018). The ubuntu story. Retrieved from https://www.ubuntu.com/about/about-ubuntu