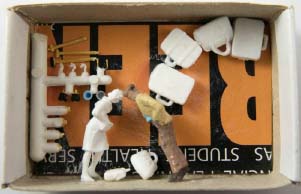

Figure 1 | Nona Cameron, Being with all that was, Matchbox representation

| Creative Arts Educ Ther (2018) 4(2):131–138 | DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2018/4/20 |

The Imperative for a Daily Reflective Practice; Reflexively Inhabiting matchboxes

The MIECAT Institute, Australia

Keywords: loss, grief, reflective practice, reflexivity, matchboxes

Looking back to the year when I was working with participants as part of my doctoral research project, Excuse me, your grief is showing (Cameron, 2016), it is clear what an unrelentingly busy time that was. Then, I was concurrently working as an arts therapist in an acute care medical setting with adolescents, and at The MIECAT Institute teaching and supervising postgraduate students. Life was very full; perhaps over full.

Recording and reflecting back to the research participants around the arts-based inquiries on which we were collaborating, was an ongoing task. This process not only formed a part of the emergent methodology, it also echoed a motivating value I had around sharing with participants so they may benefit from this iterative practice. We were co-inquiring into their lived experience of loss as it was felt and expressed in everyday ways.

In order to represent these co-inquiries in all of their complexity, I remained with the aching intimate details of them for a long time. I considered it as part of my ethical responsibility as a researcher – to look after the fragile, vulnerable explosions and showings that had dared to be revealed in the collaborations. Being so close with their experiences for so long, and remaining descriptively engaged in order to capture these as well as I could in the representations, I struggled for some time with my own authority as a researcher unable to find my own voice with which to write. I had such a strong value and ethic of not diminishing the voices of the co-researchers that it took much longer than anticipated to find how I would shape the co-inquiries for the research context and what I wanted to say. This was fraught with struggle, doubt, anxiety and insecurity for me, which in retrospect, was unsurprisingly resonant with the difficulties that participants had in finding good enough ways to share and show what had felt beyond expression in their own longing and missing. Being with experiences of absence, invited loss and all that this might entail into the intersubjective field.

Figure 1 | Nona Cameron, Being with all that was, Matchbox representation

Figure 2 | Nona Cameron, Impasse, Matchbox representation.

The challenges in writing something worth saying, initially had me writing badly, as I was caught up in unexpressed expectations, my own and others, on what research is and how it ought to appear. Several iterations of writing failed to satisfactorily carry the integrity of experiencing, or translate the vital immediacy of the expressive arts processes, and I despaired at it ever being achieved. Concurrently, I realised with all my commitments, there was little availability for simple quiet reflection, and being with the ripples of all that was happening in my life. In response to this, I ditched the writing and took time out from the doctorate, to devote to a daily reflective arts-making practice, in effect, returning to how I best make sense of things. This immersion was long overdue, and it went on longer than I had intended, lasting a total of 380 days. Every day I committed to making a small creative piece in a matchbox that, in its simplicity, captured whatever stood out as being significant from my encounters on that day. These representations were made as collaged miniature dioramas formed from felt sensing, aesthetic interests, and intuitive choosing, and were informed by whatever was pressing, pleasing or left over.

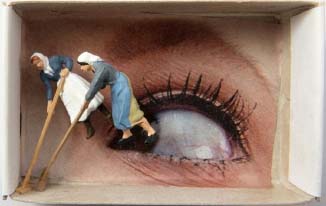

Figure 3 | Nona Cameron, Impermanence, Matchbox representation

The impulse to make this growing collection was profound as a way of gathering many things in together, with a loose purpose, without any other agenda. This felt like a fresh reflective process, uncluttered, lively.

The expression in each diorama may have been from interactions in my therapeutic or academic work, from my private life, or encounters with strangers, pets, nature, on holiday, or in solitude. I allowed myself to let go my preoccupation with the research inquiry that had been so persistent until then, broadening the focus on what I felt was important between me with others, or me in place and time. By concentrating on relational places-between in the encounter of meeting, I felt enlivened again, and was reminded of how there is something to be expressed every day from ordinary interactions. Not surprisingly, this was not unlike the manner in which the co-inquirers and I encountered their ordinary ways of being and grieving.

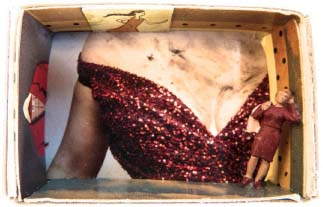

The matchboxes were about the right fit for my musings, pocket-sized, made from collaged bits of postcards, painted images, found objects, and inhabited by small figurines. These were tiny installations of my internal ‘street scenes’ (Slinkachu, 2010), made quickly in the hospital studio and pocketed, or emerging late at night on the lounge room floor. In this way, they carried aspects of my daily ordinary life. There were no plans, other than to engage with some relational reverberations that remained for me. Beginning on the outside cover, the bits of colours, textures, and images were chosen from pre-reflective urges or nudges, committed and glued, so then I’d move inwards. Opening the drawer to cover its internal surfaces as above, I’d ponder over the collection of little people I had gathered, to place them in the box’s interior in line with my own interiority. I was finding a new creative vocabulary that grew from my pre-reflective inklings and reflective noticings cohabiting. The final step was finding a title to name something of the interaction within, giving it a voice, and allowing meanings to emerge. These became surprising, ambiguous, belligerent, little boxes of paradoxes. I was drawn to depict contradicting and competing voices, with little unorthodox murmurings emerging. Allen (1995) reflects on something resonant where she notes that “as artists we are schooled in paradox; through image making we are practiced in making visible the contradictions we face” (p. 48).

Figure 4 | Nona Cameron, I see red! Matchbox representation

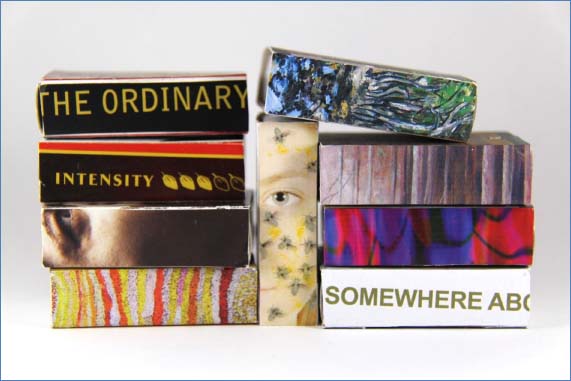

Figure 5 | Small grouping of the 380 matchboxes – collaged from postcards, found images and texts

Figure 6 | (a) Nona Cameron, What is carried, Matchbox representation, (b) Nona Cameron, Simplicity & textures of being, Matchbox representation.

These representations began to feel like messengers from the liminality or ambiguity between ways of showing and knowing, “What exists in the space between inside and outside, is an unknown relationship between self and other”, write Springgay, Irwin and Kind (2008, p.83). Opening the drawer of a matchbox reveals a scene within as little action figures interact with some aspect of ‘other’ from a moment or curiosity and me. This movement between the outside and inside creates dynamism across different aspects of what is being expressed adding another dimension to the representation. Thus, these interactions between what was hidden or is being revealed in the drawers, and the outside of the boxes carry liveliness as ways of offering stories that are not fixed but morphing and emergent depending on context and time. Just as the action of opening the draw provides an emergent aspect of the art piece for a viewer, it also has improvised elements for me, the maker, depending on the contexts in which I view them. They began as very private showings to myself, with no intention on sharing them, well not beyond a few close allies.

Figure 7 | Nona Cameron, Marking till midnight, Matchbox representation.

Figure 8 | Nona, Cameron, Introducing Asher on the Children’s Ward, Matchbox representation, hand held and magnified (Photo by Yarn Sullivan)

However, I was persuaded to share these art works to a wider audience, which led to an exhibition, Small Daily Showings (Allen & Cameron, 2013), where people were invited to interact with them. It was there that I found others shared an intense interest in the matchboxes. I was given responses by others who described how my personal reflective responses that were depicted in the work held resonances with their own experiences. Some went as far as telling me their own personal stories relating to a particular box. Given that these were intimate details of specific occurrences in my life, I was astounded that others could tell an equally detailed story of a very different kind, with personal content and contexts from their own lives. What great evidence this was of the liberation of images (McNiff, 2004), whose imaginal agencies had moved well beyond their makers’ intentions, my intentions. I realised that these matchboxes are in a perpetual state of becoming-known.

These curious interactions led me to inquire further with the art pieces as to whether they might in fact speak to some aspects of my research from the previous year. With this new focus, I came to realise that I had indeed been processing much of the collaborative experiences with the co-researchers seen in a number of the representations that explored themes around grief and loss. Many of the relational meetings depicted within, were richly descriptive of meaningful encounters from our intersubjectivity, carrying significances beyond their first intention of expression, and in this way, the expressions were both specific, and more generally resonant, little boxes of ambiguity. The artworks became a resource from which to write and represent the co-inquiries that gave greater attention to an aesthetic sensibility.

Figure 9 | Nona Cameron, Wish you were here! Matchbox representation (Photo by Juan SemoGrogan)

Over time, I found making and engaging with these matchboxes a powerful means of sense

making. They connected me reflexively with my embodied knowing that encouraged a different expressive way of showing what remained as important, not only in my research, but also in my work and life in general. I had experienced monumental loss a number of years earlier where my youngest child, Asher, at 12 years of age, had been killed in a boating accident. My own ordinary grieving was still keenly finding ways of being expressed. These robust and fragile pocket-sized reflections had become touch stones worthy of note, as they carried moments of being with others, of missing, absences, and longings of my own sense of living in loss. They were, and still are, reflexive engagements that feel lively and necessary.

About the Author

Dr Nona Cameron is a therapeutic arts practitioner and academic at The MIECAT Institute and in her private practice in Melbourne. For nearly 5 years, she was a creative arts therapist with adolescents at a busy urban hospital, mostly working with young people with eating disorders and running an art studio on the wards. Prior to this she ran an afterschool art studio for children for several years and worked as a research assistant on projects, such as the Yanyuwa cultural atlas of the Gulf of Carpentaria. She has a background in printmaking, environmental activism and a love of gardening. Practicing permaculture in small suburban gardens has sustained her as she raised her 3 children.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Allen, J. & Cameron, N. (2013). Matchbox Moments: a year in reflection. [Exhibition catalogue]. Small Daily Showings. The MIECAT Institute, Melbourne, Australia.

Allen, P. (1995). Art is a Way of Knowing: a guide to self-knowledge and spiritual fulfilment through creativity. Boston, MA: Shambala Publications.

Cameron, N. (2016). Excuse me, your grief is showing: an inquiry into sharing everyday loss. (Doctoral dissertation, The MIECAT Institute). Retrieved from http://au.blurb.com/b/7763706-excuse-me-your-grief-is-showing

McNiff, S. (2004). Art Heals: How creativity cures the soul. Boston, MA: Shambala Publications.

Slinkachu, (2010). Big Bad City. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Lebowski.

Springgay, S., Irwin, R., & Kind, S. (2008). A/R/Tographers and Living Inquiry, in G Knowles & A Cole (Eds), International Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research (pp. 83–92). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.